Abstract

The effect of the protein kinase C (PKC) activator 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG) on TTX-sensitive Na+ currents in neocortical pyramidal neurones was evaluated using voltage-clamp and intracellular current-clamp recordings.

In pyramid-shaped dissociated neurones, the addition of OAG to the superfusing medium consistently led to a 30 % reduction in the maximal peak amplitude of the transient sodium current (INa,T) evoked from a holding potential of −70 mV. We attributed this inhibitory effect to a significant negative shift of the voltage dependence of steady-state channel inactivation (of approximately 14 mV). The inhibitory effect was completely prevented by hyperpolarising prepulses to potentials that were more negative than −80 mV. A small but significant leftward shift of INa,T activation was also observed, resulting in a slight increase of the currents evoked by test pulses at potentials more negative then −35 mV.

In the presence of OAG, the activation of the persistent fraction of the Na+ current (INa,P) evoked by means of slow ramp depolarisations was consistently shifted in the negative direction by 3.9 ± 0.5 mV, while the peak amplitude of the current was unaffected.

In slice experiments, the OAG perfusion enhanced a subthreshold depolarising rectification affecting the membrane response to the injection of positive current pulses, and thus led the neurones to fire in response to significantly lower depolarising stimuli than those needed under control conditions. This effect was attributed to an OAG-induced enhancement of INa,P, since it was observed in the same range of potentials over which INa,P activates and was completely abolished by TTX.

The qualitative firing characteristics of both the intrinsically bursting and regular spiking neurones were unaffected when OAG was added to the physiological perfusing medium, but their firing frequency increased in response to slight suprathreshold depolarisations.

The obtained results suggest that physiopathological events working through PKC activation can increase neuronal excitability by directly amplifying the INa,P-dependent subthreshold depolarisation, and that this facilitating effect may override the expected reduction in neuronal excitability deriving from OAG-induced inhibition of the maximal INa,T peak amplitude.

Depolarisation-activated ion flux through Na+ channels plays a primary role in neuronal excitability by sustaining the generation of somatic action potentials (APs), and also contributes towards the information processing that takes place in dendritic arborisation (Stuart & Sakmann, 1994; Schwindt & Crill, 1995; Mittmann et al. 1997). Various physiological and pathological events can modulate voltage-gated Na+ channel function (and therefore significantly affect neuronal excitability), some of which have been shown to operate through the activation of second messenger systems (see reviews by Catterall, 1992, and Cukierman, 1996). Moreover, changes in the peak amplitude of the transient Na+ current (INa,T) or in Na+ channel gating properties have been directly demonstrated by means of experimental manipulations aimed at inducing channel phosphorylation using cAMP-dependent protein kinase (Li et al. 1992) or protein kinase C (PKC) (Dascal & Lotan, 1991; Numann et al. 1991; Godoy & Cukierman, 1994a,b; Astman et al. 1998). The effect of the PKC-operated modulation of Na+ channels seems to be rather complex and probably varies in different neuronal populations and has variable effects on the activation (Dascal & Lotan, 1991) and inactivation (Numann et al. 1991) kinetics of INa,T. However, direct cell exposure to diacylglycerol-like substances has consistently been found to lead to different degrees of reduction in INa,T amplitude in cultured hippocampal neurones, as well as in cell lines expressing brain Na+ channels (Numann et al. 1991; Dascal & Lotan, 1991; Godoy & Cukierman, 1994a,b). This effect is expected to cause a significant decrease in cell excitability, but an opposite effect has recently been suggested by Astman et al. 1998, on the basis of evidence showing that the activation of the persistent fraction of the Na+ current (INa,P) in the presence of PKC-activator phorbol ester shifts to more negative potentials and thus leads to increased cell excitability. It has been demonstrated that the small, persistent component of the Na+ current sustains a number of the depolarising subthreshold events occurring in cortical neurones (Stafstrom et al. 1982, 1985; Franceschetti et al. 1995, 1998; Azouz et al. 1996; see review by Crill, 1996), and contributes towards the generation of pathological depolarisations in experimental models of human neurological diseases (Segal, 1994; Bennett et al. 1995; Cannon, 1996; Segal & Douglas, 1997; Kapoor et al. 1997).

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effect of PKC activation on both the transient and the persistent fraction of the Na+ current in acutely dissociated cells, in order to gain a better understanding of the net effect of PKC-dependent Na+-channel phosphorylation on neocortical pyramidal neurones. Intracellular recordings in neocortical slices were also made in order to evaluate the effect of PKC activation on Na+-dependent depolarising potentials.

METHODS

Slice and cell preparation

Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Italy) aged 10–25 days were anaesthetised with an intraperitoneal injection of chloralhydrate (1 ml (100 g body weight)−1 of a 4% solution; Fluka) and decapitated. Their brains were removed and placed in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (mm): 114 NaCl, 24 NaHCO3, 1 CaCl2, 1 NaH2PO4, 8 MgCl2, 2.5 KCl and 20 glucose, and bubbled with 95 % O2-5 % CO2. Coronal slices with a thickness of 300–350 μm were cut from the sensorimotor cortex using a vibratome. The slices used for the current clamp experiments were immediately transferred to an interface chamber, perfused with ACSF and allowed to equilibrate for 1–1.5 h before the electrophysiological recordings were started. The slices used to prepare the dissociated neurones were kept for 8–10 min in a modified ACSF (bubbled with 95 % O2-5 % CO2, pH 7.4), in which NaHCO3 was replaced with 10 mm Hepes-NaOH, and which contained 1 mm kynurenic acid and 1 mg ml−1 protease Type XIV (Sigma) in order to digest the extracellular matrix. After enzyme treatment, the slices were washed and stored in an enzyme-free solution. At the recording times, the neurones were dissociated using fire-polished Pasteur pipettes, plated in a Petri dish (Costar) coated with Concanavalin A, left for 2–3 min to allow attachment, and then bath perfused with modified ACSF (see below). Only the pyramid-shaped neurones were selected for patch-clamp recordings. All the experimental procedures were carried out according to the 86/609/CEE law and to the guidelines for animal care and management of the Carlo Besta Institute Ethics Committee.

Electrophysiological recordings

Patch-clamp whole-cell recordings

Recordings of isolated neurones were made at room temperature using a RK 400 patch-clamp amplifier (BioLogic) and Axopatch 200B (Axon Instruments). Borosilicate glass electrodes were filled with a solution containing (mm): 75 CsF, 55 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 EGTA-CsOH, 10 Hepes-CsOH, 2 Na2ATP, 10 phosphocreatine-diTris, and 20 U ml−1 creatine phosphokinase, pH 7.2 (3–6 MΩ). After seal formation and cell membrane rupturing, capacitive currents were minimised by means of the amplifier circuitry. A 70–90 % series resistance compensation was routinely achieved and the estimated maximum voltage-clamp error did not exceed 4 mV. The data were digitised by means of a Digidata 1200 interface (Axon Instruments), and pCLAMP6.0 software (Axon Instruments) was used to generate stimulus protocols and acquire signals. The residual transients and leakage currents were eliminated using a P/4, on-line subtraction protocol.

In order to isolate the Na+ currents, the neurones were bath perfused with a modified ACSF containing (mm): 120 NaCl, 1.3 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 0.4 CdCl2, 0.3 NiCl2, 3 KCl, 20 tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA-Cl), 10 Hepes-NaOH, 10 glucose, pH 7.3, bubbled with pure oxygen. In most of the experiments aimed at recording fast Na+ currents, the amount of NaCl was reduced to 15 mm and partially substituted with choline chloride (110 mm) in order to reduce current amplitudes and series-resistance voltage-clamp errors.

In whole-cell configuration, the Na+ currents were evoked using rectangular depolarising steps and, when useful, the linear leak was corrected using the P/4 subtraction protocol. INa,P was evoked by means of slow (24 mV s−1) voltage ramps (three ramps per trial). Junction potential errors were not corrected. The sampling frequency was, respectively, 10 and 5 kHz for the voltage steps and ramp protocols. The membrane currents were filtered at 3 kHz (voltage steps) or 1 kHz (voltage ramps). The recordings with voltage-clamp errors were excluded from the analysis.

Intracellular recordings in slices

These were made on layer V pyramidal neurones using an IR-283 amplifier (Neurodata Inst. Corp., NY, USA). The bath temperature was kept at 37°C. Sharp electrodes were prepared using borosilicate glass capillaries (Clark Electromedical Instruments) and filled with 3 M potassium acetate (resistance 80–90 MΩ). Only healthy neurones with a stable spontaneous resting membrane potential (Vrest) that was more negative than −60 mV, a stable firing level and overshooting APs were selected for the analysis. After neurone impalement and in order to isolate Na+-dependent potentials, the slices were bath perfused with a modified ACSF containing (mm): 30–60 TEA-Cl equimolarly substituting NaCl (to a final concentration of 124) and 0.2 CaCl2, 7 MgCl2, 2 CoCl2, 24 NaHCO3, 10 glucose (pH 7.4), bubbled with 95 % O2-5 % CO2. CsCl (3–6 mm) was added in most of the experiments in order to block the anomalous rectifying current. In a few control experiments, CsCl was increased to 20 mm, or 1 mm BaCl2 was added to the modified ACSF. The voltage and current signals were displayed on an analogic oscilloscope, stored on magnetic tape, and digitised using an AT-MIO-16-E A/D converter (National Instruments, Austin, USA) at a sampling rate of 4–10 kHz.

Drugs

1-Oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG, Sigma) was dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO, 0.1 % v/v), stored at −20°C, and added to the superfusing medium at a final concentration of between 2 and 20 μm. In a few patch-clamp experiments, OAG (2 μm) was added to the pipette-filling solution and intracellularly perfused, but extracellular perfusion was preferred because of the possibility of obtaining sufficiently long control recordings. Due to its apparently faster inhibitory action, the PKC inhibitor 1-(5-isoquinolinesulfonyl)-2-methyl-piperazine (H7, Tocris; 20 μm) was preferred as a means of preventing OAG action in dissociated neurones, whereas the other inhibitor chelerythrine chloide (20 μm; Sigma) was used in slice experiments after at least 1 h of preincubation. A number of control experiments were made in order to evaluate the current traces throughout the long-lasting perfusions with modified ACSF alone or DMSO (at the same concentration as that used to dissolve OAG).

Data analysis

Current recordings in voltage-clamp experiments

The data were analysed using pCLAMP (Axon Instruments) and Origin 4.0 software (Microcal Inc.) on a Pentium 166 MHz PC. The activation curves were obtained by fitting the data points with the Boltzmann equation in the form: G/Gmax= 1/{1 + exp((V1/2−V)/k)}, where Gmax is the maximal peak conductance, G the peak conductance at each test voltage, V1/2 the voltage at which half-maximal activation is reached, and k the slope factor. Steady-state inactivation curves were obtained by fitting the data points with the Boltzmann equation in the form: I/Imax= 1/{1 + exp((V1/2−V)/k)}, where I/Imax is the relative current.

Current clamp recordings in slices

The voltage traces obtained from the intracellular recordings were analysed on a PC using home-made programs. Input resistance (Rin) was measured by symmetrically hyperpolarising and depolarising current-pulse injections, and expressing the result as the V-I relationship measured 200 and 400 ms after the onset of the pulse. The membrane time constant was evaluated using a single exponential function to fit the membrane voltage deflection in response to a 0.2–0.25 nA step current injection. The potential at which the membrane depolarisation speed became greater than 15 V s−1 was assumed to be the spike threshold level.

The data are expressed as mean values ±s.e.m., and were statistically analysed using Student’s two-tailed t test for paired data or the Mann-Whitney U test.

RESULTS

The whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were obtained from 48 acutely dissociated ‘pyramidal-shaped’ neurones, and intracellular recordings from 21 pyramidal neurones in layer V of sensorimotor cortex slices.

Patch-clamp recordings in isolated neurones

Effect of OAG on the transient Na+ current. Most of the experiments aimed at evaluating the effect of OAG on INa,T were performed after partially replacing NaCl with choline chloride (see Methods) in order to reduce voltage-clamp errors due to the large INa,T amplitude normally observed in pyramidal neocortical neurones. A few experiments aimed at evaluating both INa,T and INa,P in the same cell were performed using physiological extracellular Na+ concentrations.

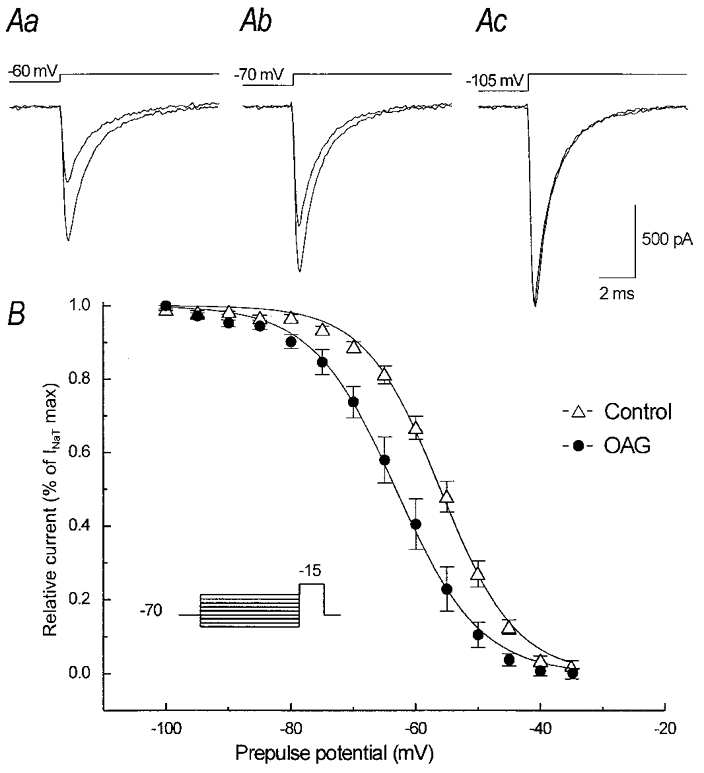

The effects of OAG on INa,T amplitude were first evaluated in currents evoked from the general holding potential level of −70 mV, which is close to the spontaneous Vrest in neocortical pyramidal neurones. As shown in Fig. 1A, OAG consistently decreased the peak amplitude of INa,Ts elicited by test pulses to −15 mV (Fig. 1Ab) by an average of about 30 % (30.1 ± 3.3 %, P < 0.0001, n= 12), a result that was even more evident when they were evoked starting from more positive conditioning potential levels (i.e. −60 mV: see Fig. 1Aa); however, when the currents were evoked from conditioning potentials that were more negative than −80 mV (Fig. 1Ac), the INa,T peak amplitude remained unchanged or slightly increased. Given that these findings may be explained assuming that OAG reduces the amount of Na+ channels available for activation only at relatively positive holding potentials, its effects on the voltage dependence of INa,T steady-state inactivation were investigated in detail by delivering 300 ms conditioning prepulses at voltage levels between −105 and −35 mV before the standard test pulse at −15 mV. The results of the application of this protocol revealed that OAG consistently shifted the voltage dependence of INa,T steady-state inactivation in a negative direction. The average, normalised steady-state inactivation plots under control conditions and in the presence of OAG are shown in Fig. 1B. Boltzmann fittings of the individual steady-state inactivation plots obtained in eight neurones after normalisation to the maximal current amplitude in each neurone returned V1/2 values which averaged −56.3 ± 0.2 mV under control conditions and −70.6 ± 0.2 mV after 3–5 min of OAG perfusion (P < 0.001, n= 8). The mean values of the slope constants (k) were, respectively, 6.0 ± 0.2 and 6.6 ± 0.1 mV e-fold−1; P < 0.001.

Figure 1. Effect of 2 μm OAG on INa,T steady-state inactivation.

Aa-c, current traces obtained in the same neurone by means of a depolarising step to −15 mV preceded by a 300 ms prepulse at various potentials (the stimulus protocol is shown in the inset of B). The largest current peaks were obtained after a prepulse to −100 mV and were unchanged after OAG, but the inhibition of the current peak becomes evident after prepulses to −70 mV and −60 mV. B, steady-state inactivation curve obtained by plotting the current peaks (normalised to their maximal values) versus the prepulse potential. The continuous lines are fitted curves obtained by means of a Boltzmann function applied to the data points calculated under control conditions and in the presence of OAG.

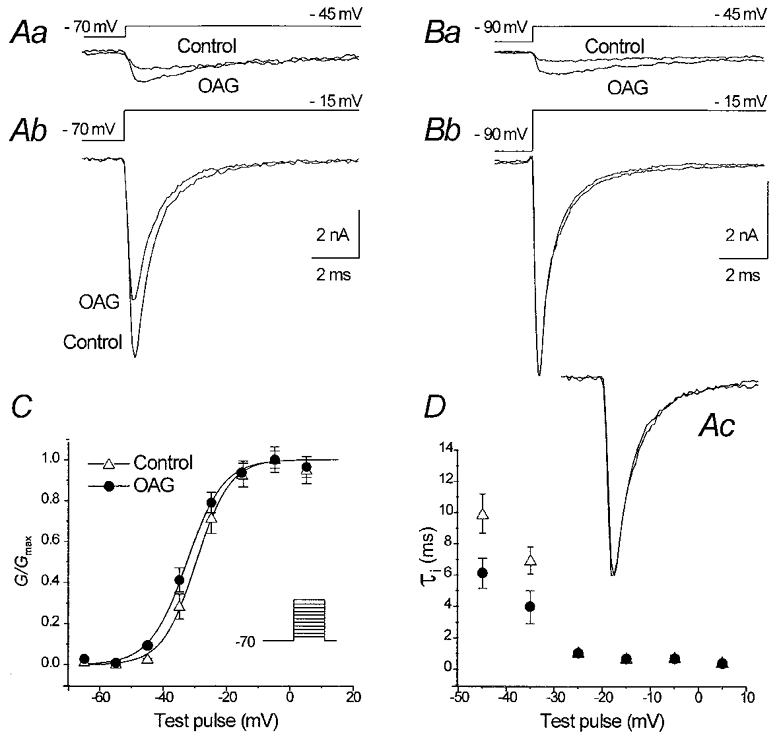

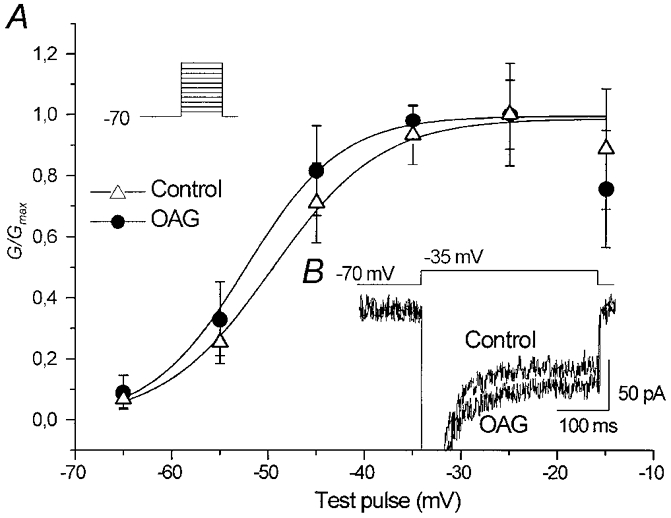

Figure 2 shows the effects of OAG on INa,T activation. In neurones held at a potential of −70 mV (Fig. 2Aa and b), the reduction in INa,T peak amplitude was consistently observed using depolarising test pulses more positive than −35 mV (Fig. 2Ab), whereas the currents evoked by test pulses at more negative voltage levels were slightly increased (Fig. 2Aa) thus suggesting a small hyperpolarising shift of INa,T activation. Figure 2C shows the INa,T activation curves obtained in 12 neurones held at −70 mV. The data points were derived by averaging normalised conductances (G/Gmax) and fitted by means of a Boltzmann function. The Na+ conductances (GNa) were calculated from the equation GNa=INa,T/(V − VNa) (where INa,T is the peak of the inward current, V the command potential and VNa the theoretical reversal potential of +33.8 mV, according to the experimental conditions). The voltage at which half-maximal activation (V1/2) was reached was −29.7 ± 1.1 mV under control conditions and −32.7 ± 0.8 mV in the presence of OAG (P < 0.02); the slope factor of the curve (k) slightly increased from 5.3 ± 0.9 to 5.7 ± 0.7 mV e-fold−1 (P < 0.02). The leftward shift of current activation was found to be strictly time locked to the beginning of OAG perfusion and did not appear to be a spontaneous, progressive change. It was undetectable in response to repeated activation protocols applied before OAG perfusion, and was blocked by the PKC inhibitor H7 (10 μm; data not shown; n= 4 neurones). To further analyse the characteristics of the inhibitory effect exerted by OAG on INa,T peak amplitude, control experiments were performed in which the neurones (n= 4) were held at a potential of −90 mV. As shown in Fig. 2Bb, the OAG-dependent inhibition of the maximal INa,T peak amplitude in a representative neurone held at −90 mV was completely prevented, whereas the amplitude of the current evoked in response to a step depolarisation to −45 mV was slightly increased (Fig. 2Ba).

Figure 2. Effects of 2 μm OAG on INa,T activation and fast inactivation time course.

Aa and b, INa,T traces recorded in a representative neurone in response to two different voltage steps under control conditions and in the presence of OAG. Ba and b, INa,T traces evoked in a neurone held at −90 mV, showing a slight increase of the current evoked using a depolarising pulse to −45 mV, but no decrease in maximal current peak amplitude in response to a depolarising pulse to −15 mV. C, voltage-dependent Na+ conductance evaluated in 14 neurones (the stimulus protocol is shown in the inset); the curves give the Boltzmann function fit applied to the data points calculated under control conditions and in the presence of OAG, normalised to the maximal values, respectively, obtained in the two experimental conditions. D, plot of the voltage dependence of the fast time constants (τi) of the INa,T decay (symbols as in C). In the inset Ac, the same traces as in Ab are scaled at the same amplitude to show the overlap of the fast inactivation time course under control conditions and in the presence of OAG.

The fast time constant (τi) of the decay of the currents evoked by low-amplitude depolarising steps appeared to be smaller in the presence of OAG than under control conditions (6.1 ± 0.9 vs. 9.9 ± 1.2 ms at −45 mV, and 3.9 ± 1.9 vs. 6.9 ± 0.8 ms at −35 mV; P < 0.05; Fig. 2D). This effect could be attributed to the OAG-dependent leftward shift of INa,T voltage dependence, which is also expected to accelerate the current kinetics at a given, submaximal activation level. No difference was detectable in the τi measured in currents evoked at more positive potentials (τi= 0.5 ± 0.08 ms under control conditions and 0.4 ± 0.1 ms in the presence of OAG, at −15 mV). Accordingly, the TTX-subtracted current traces evoked by a step stimulus to −15 mV in the presence of OAG completely overlapped those obtained under control conditions when scaled to the same amplitude (Fig. 2D, inset).

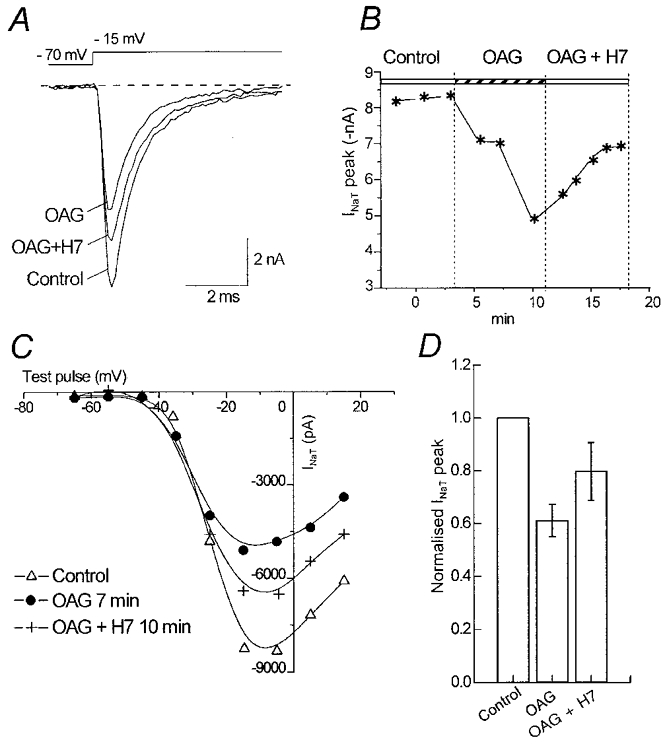

Preincubation with the PKC inhibitor H7 (10 μm) prevented the effects of OAG (n= 3 neurones). After the administration of OAG, a partial recovery of its effects on INa,T peak amplitude could be obtained by co-perfusing the cell with both OAG and H7 for several minutes (Fig. 3A–C), and the maximal peak amplitude of INa,T which had been reduced to 61.5 ± 5.3 % in the presence of OAG (n= 4 neurones), recovered to 79.7 ± 9.6 % of the control value (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. Partial recovery of INa,T peak amplitude obtained after OAG-induced inhibition.

A, INa,T traces using a step potential to −15 mV under control conditions, in the presence of OAG and 10 min after the onset of perfusion with 2 μm OAG plus the PKC inhibitor H7 (10 μm). B, time course of the reduction and recovery of the maximal INa,T peak amplitude, respectively, during OAG perfusion and in the presence of OAG plus H7. C, current-voltage relationship obtained under the three different conditions. D, mean decrease and subsequent recovery of the INa,T peak amplitude (step potential to −15 mV) in four neurones perfused with OAG and with OAG plus H7.

Effect of PKC activation on the persistent fraction of the Na+ current

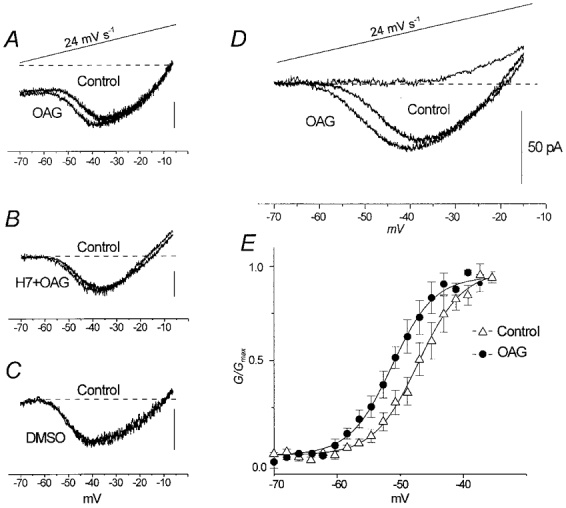

In most of the experiments, INa,P was evoked by means of depolarising ramp potentials (from −70 to +10 mV at a rate of 24 mV s−1), which was slow enough to avoid transient Na+ channel opening and consistently capable of evoking the small, persistent, TTX-sensitive Na+ current. In agreement with previous findings in cortical neurones (French et al. 1990; Alzheimer et al. 1993; Brown et al. 1994; Magistretti & Alonso, 1999), INa,P begins to activate between −60 and −50 mV, with a peak at about −40 mV. After membrane rupturing, and holding the cell at −70 mV, INa,P amplitude often progressively increased to a steady level that varied from cell to cell, with a peak ranging from −19.8 to −66.0 pA (mean −37.2 ± 11.2 pA). The addition of 2 μm OAG to the perfusing medium induced a small but consistent leftward shift of the voltage dependence of INa,P activation (see Fig. 4A for a representative neurone), which was prevented by preincubation with PKC inhibitors (n= 3 neurones; Fig. 4B). No changes in current activation were observed during the control experiments in which the neurones were perfused with DMSO at the same concentration (0.1 %) as that used to dissolve OAG (n= 2 neurones; Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Effect of 2 μm OAG on INa,P.

A, INa,P evoked by a slow ramp voltage protocol (top trace). B, INa,P traces obtained under control conditions and in the presence of OAG added to the PKC inhibitor H7 (10 μm). C, INa,P traces recorded at the onset and 10 min after the onset of perfusion with DMSO at the same concentration used to dissolve OAG. D, mean of INa,P traces obtained from 14 neurones; the mean traces obtained in five of these neurones after TTX perfusion is also shown. E, plot of INa,P activation curve: the data points are the mean conductances normalised to maximal values under control conditions and in the presence of OAG (n= 14) plotted against the command potentials. The continuous line is the mean of 14 fitting curves obtained by means of a Boltzmann relationship.

Figure 4D shows the voltage dependence of the ramp-activated INa,P obtained by averaging the current traces recorded in 14 neurones. The normalised conductances (G) derived from the same neurones were fitted, in the voltage range from −70 to −35 mV, by means of Boltzmann functions (Fig. 4E). The V1/2 was −47.1 ± 0.02 mV under control conditions and −51.0 ± 0.02 mV in the presence of OAG (P < 0.002), without any significant change in the slope of the fitting curve (k= 3.4± 0.02 and 3.3 ± 0.02 mV e-fold−1, respectively). The mean peak amplitude of INa,P was slightly, but not significantly, larger after OAG.

In virtually all the recordings, a contaminating outward current was activated by depolarising ramps at potential levels that were more positive than −35 mV. This current, which was identified with the ICat originally described by Alzheimer (1995), normally prevented the correct evaluation of INa,P behaviour in the rightmost part of ramp-activated currents. However, the mean current trace obtained from five neurones after TTX blockade of the Na+ currents clearly showed that this current becomes detectable in a range of potentials that are consistently more positive than those corresponding to INa,P activation and peak.

The effect of OAG on INa,P was also evaluated using the current traces obtained in response to 300–350 ms depolarising pulses from a holding potential of −70 mV in six neurones perfused with physiological external concentrations of NaCl. The amplitudes of the current remaining after INa,T inactivation was measured on the traces obtained under control conditions and in the presence of OAG, digitally subtracted by those obtained in the presence of OAG plus TTX. OAG slightly increased the amplitude of this current fraction when activated by step potentials more negative than −25 mV, but this increase was only significant for the currents evoked by voltage steps to potentials ranging from −55 to −35 mV (P < 0.03). Figure 5 shows the conductance values calculated from the current amplitudes plotted against test voltage: the mean data points were fitted with a Boltzmann function within the voltage range of −65 to −15 mV, returning V1/2 values of −45.8 ± 2.4 mV under control conditions, and −51.0 ± 2.4 mV in the presence of OAG (P < 0.03), without any significant change in the slope factor (k= 6.8± 1.5 and 5.2 ± 1.3 mV e-fold−1, respectively).

Figure 5. Effect of OAG on INa,P evoked by voltage steps.

A, plot of the Na+ conductance calculated from the INa,P amplitude at the end of 350 ms voltage pulses (the stimulus protocol is shown in the inset). The data points are the mean conductance values obtained by measuring (n= 6 neurones) the current plateau under control conditions and in the presence of OAG, plotted against the command potentials and fitted by means of a Boltzmann function. The TTX-subtracted current traces recorded in a representative neurone in response to a voltage step at −35 mV are shown in B.

Effect of OAG on Na+-dependent potentials recorded in slices

The effect of OAG was also evaluated in neocortical pyramidal neurones recorded in situ in layer V. The injection of depolarising pulses or ramps in these neurones gives rise to a depolarising rectification that causes significantly larger deflections of membrane potential (Vm) than those induced by negative pulses of the same magnitude. This depolarising rectification is known to be sustained by INa,P (Stafstrom et al. 1982, 1985) and is especially evident in response to depolarisations that are just below the threshold level, thus accounting for the non-linear response observed when the membrane approaches the firing level. Given the prominent contribution of INa,P to the subthreshold and firing properties of intrinsically bursting (IB) layer V pyramidal neurones (Franceschetti et al. 1995; Guatteo et al. 1996), we concentrated on the effects of OAG on this neuronal subclass. A few (n= 4) regularly spiking (RS) neurones were also tested with the aim of qualitatively comparing the effects of OAG on the two neuronal phenotypes.

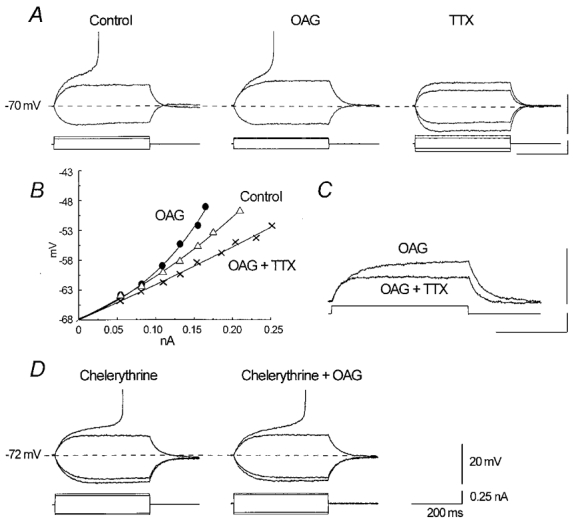

All the intracellular recordings were started with the neurones in normal ACSF in order to evaluate their firing properties under physiological conditions. Subsequently, a modified medium was perfused in which Ca2+ was replaced by Co2+; the K+ currents were substantially blocked by high (30–60 mm) TEA concentrations, and the anomalous rectifying current was blocked or greatly reduced by 6–20 mm CsCl. The neurones were left at their spontaneous Vrest(−70.0 ± 0.9 mV) or slightly hyperpolarised at Vm values ranging from −70 to −75 mV. The small changes in Vm that occasionally occurred during the recording period were corrected by injecting small DC currents. OAG (5–25 μm) was added to the modified medium 40–60 min later, when the neurones regularly showed a steady subthreshold and threshold behaviour. The addition of OAG clearly enhanced depolarising rectification, thus leading to greater membrane depolarisation in response to depolarising pulses at just below threshold levels, and determining a highly significant increase in apparent Rin values. The addition of BaCl2 (1 mm) in order to block the M-current (Selyanko & Sim, 1998) (Fig. 6A and B), or the application of high external concentrations of CsCl (20 mm; data not shown) in order to minimise the Na+-activated K+ current (Bischoff et al. 1998), did not modify the amplifying effect of OAG on subthreshold and near-threshold depolarising rectification. All these OAG effects were prevented by incubating the slices with the PKC inhibitors chelerythrine or H7 (n= 3 neurones), and the depolarising rectification was completely abolished by the administration of 1 μm TTX (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. Effect of 12.5 μm OAG on subthreshold and threshold membrane behaviour.

Two representative neurones perfused with modified ACSF containing 40 mm TEA, 1 mm BaCl2, 10 mm CsCl and 2 mm CoCl2. A, in a potential range close to the firing threshold, the membrane deflection in response to depolarising current pulses is greater in the presence of OAG than under control conditions, and the current pulse leading to AP generation is significantly smaller. The addition of 1 μm TTX leads to merely passive membrane behaviour. B, voltage-current plot showing the rectifying time course of membrane deflection in response to a family of depolarising pulses, which is enhanced in the presence of OAG and abolished by TTX. C, superimposition of two sweeps selected from the recordings obtained in the same neurone as in A, showing the complete block of depolarising rectification after the addition of TTX. D, preincubation with the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine (20 μm) prevents the effect of OAG. The calibration values apply to all panels.

In order to quantify the changes in subthreshold behaviour observed during OAG perfusion, the neurones were repeatedly tested using families of depolarising current pulses with regularly stepped amplitude increases of 0.01–0.02 nA. The changes of Rin values were estimated by measuring in each neurone the amplitude of the voltage deflection generated 200 ms after the onset of the injected current pulses. The Rin values measured on the largest subthreshold depolarisation in the presence of OAG were found to be significantly higher than those obtained in response to an equal current pulse (0.11 ± 0.01 nA) under control conditions (128.9 ± 11.8 vs. 97.8 ± 10.0 MΩ; P < 0.001, n= 11), with a mean increase of 35.6 ± 6.9 %. In the majority of the neurones, Rin also slightly increased in the hyperpolarising direction (99.5 ± 8.8 vs. 87.4 ± 8.1 MΩ, a mean increase of 14.7 ± 3.4 %; P= 0.03), probably because of a PKC-dependent modulation of residual anomalous rectifying currents (Cathala & Paupardin-Tritsch, 1997). The ratio between the Rin measured using depolarising and hyperpolarising current pulses of the same amplitude was 1.11 ± 0.03 under control conditions and 1.31 ± 0.04 in the presence of OAG (P < 0.001). The membrane time constant determined on the membrane-potential deflections elicited by the hyperpolarising current pulses was similar under control and OAG-treatment conditions (42.1 ± 8.2 vs. 44.3 ± 9.2 ms).

The enhanced INa,P-dependent depolarising rectification in the presence of OAG led the neurones to reach the AP generation threshold in response to significantly lower amplitude depolarising pulses than under control conditions (0.13 ± 0.1 vs. 0.17 ± 0.02 nA; P < 0.0005). The AP generation threshold became slightly more negative than under control conditions (−49.7 ± 0.7 vs.−48.2 ± 0.8 mV; P < 0.01), the AP amplitude slightly decreased from 100.7 ± 3.0 to 96.6 ± 3.0 mV (P < 0.007), and the slope of AP decreased from 245.2 ± 25.4 to 196.6 ± 25.4 V s−1 (P < 0.0003). All these changes were observed shortly (7–15 min) after the onset of OAG perfusion, and remained the same during long-lasting perfusion (30–80 min).

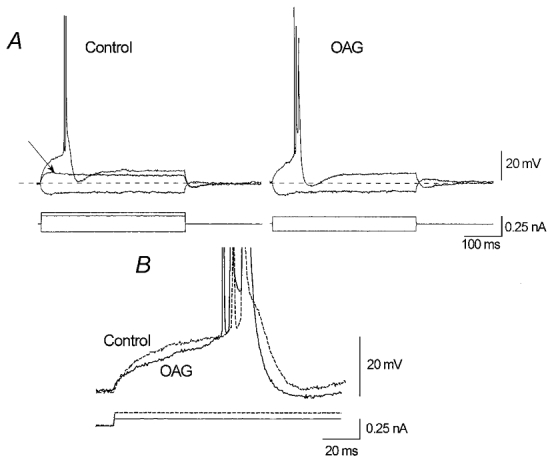

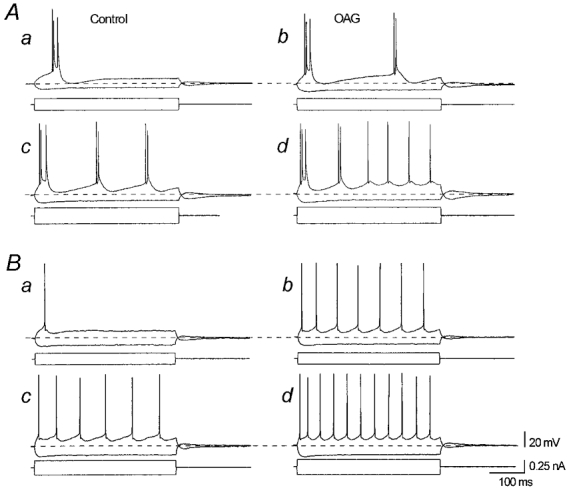

In order to evaluate the effect of OAG-induced PKC activation on firing properties, control experiments were carried out in six pyramidal neurones perfused with normal ACSF. OAG failed to induce any significant change in Vrest or qualitative firing. The intrinsically bursting neurones (which normally discharged with a single burst in response to threshold stimuli under control conditions) preserved their bursting behaviour after OAG perfusion but reached the threshold in response to depolarising stimuli with a lower amplitude. The duration of an individual burst was unaffected or slightly lengthened (n= 3 neurones) to include one more spike than under control conditions (Fig. 7A and B). The burst could recur during slightly above-threshold depolarisations that only evoked a single burst under control conditions (Fig. 8Aa and b). Slightly larger depolarising current pulses led to the discharge of rhythmic individual APs with a frequency of 20–30 Hz (Fig. 8Ad), each followed by a depolarising after-potential. The RS neurones (n= 3) were less obviously capable of reaching the AP generation threshold but, in the presence of OAG, their firing rate increased in response to the injection of just-suprathreshold depolarising current pulses (Fig. 8B).

Figure 7. OAG effect on an IB neurone recorded in physiological ACSF.

A, the injection of a low amplitude depolarising current pulse equal to that sustaining a subthreshold membrane depolarisation under control conditions (left panel, arrow) is capable of leading the neurone to fire with a burst in the presence of OAG (12.5 μm; right panel). B, threshold depolarisation under control conditions (dashed line) needs a larger pulse than that necessary in the presence of OAG.

Figure 8. Effects of OAG on the firing characteristics of two different neurones.

The left panels show neuronal firing under control conditions; the right panels show the response to an identical current pulse injection in the presence of OAG (12.5 μm). A, threshold response of an IB neurone to a depolarising pulse injection (a); in the presence of OAG, an equal pulse led to a discharge with repetitive bursts (b). Under control conditions, the same neurone responding to a larger current injection with repetitive short burst (c) changes its firing behaviour to two initial bursts followed by a tonic rhythmic discharge of individual APs superimposed on a membrane depolarisation (d). B, threshold (a) and slightly suprathreshold (c) firing of an RS neurone showing an increased firing rate in the presence of OAG (b and d).

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that OAG-induced PKC activation is capable of promoting increased excitability in neocortical pyramidal neurones, despite the fact that it reduces the maximal amplitude of transient Na+ currents in neurones held at −70 mV. This effect can be primarily accounted for by an increase in the depolarising contribution of INa,P which was enhanced at membrane potentials close to those generating APs and led to a significant increase in the near-threshold depolarising rectification found in our current- clamp recordings performed in slices. We attributed this depolarising rectification to the persistent fraction of the Na+ current since it was observed in the same range of potentials over which INa,P is activated, remained unaffected after the contribution of Ca2+ and K+ currents was minimised by the use of extracellular blockers, and was completely abolished by TTX.

Effects of PKC-operated channel phosphorylation on Na+ currents

In dissociated neocortical neurones OAG perfusion was found to modify both activation and inactivation properties of INa,T, and to shift the activation of the persistent fraction of the Na+ current in a negative direction.

The changes in the voltage dependence of INa,T steady-state inactivation, and the small leftward shift of its voltage dependence of activation are expected to have different functional effects depending on the membrane potential from which the current is evoked and the amplitude of the stimulus. The reduction that we found in the peak amplitude of maximal INa,T evoked from a membrane potential of −70 mV is similar to that previously reported as being due to PKC-dependent Na+ channel phosphorylation in hippocampal dissociated neurones and in cell lines expressing Na+ channels (Numann et al. 1991; West et al. 1991; Dascal & Lotan, 1991; Godoy & Cukierman, 1994a,b; Cantrell et al. 1996; O’Reilly et al. 1997). However, our experiments showed that the inhibitory effect on the INa,T peak was mainly attributable to a leftward shift of the voltage dependence of steady-state channel inactivation, in agreement with the evidence previously obtained by Godoy & Cukierman (1994a) in neuroblastoma cells exposed to diacylglycerol. Indeed, this effect was voltage dependent, becoming increasingly evident with rising positive conditioning prepulses but was prevented by hyperpolarising prepulses to potentials that were more negative than −80 mV. This finding suggests that PKC-operated phosphorylation may inhibit INa,T peak amplitude by increasing the number of channels going towards a closed→inactivated transition, which already partially occurs at ‘resting’Vm, and is greatly enhanced by steady subthreshold membrane depolarisations. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that no inhibitory effect could be observed when INa,T was elicited by families of depolarising pulses from a holding potential of −90 mV. This finding is in line with the data reported by Godoy & Cukierman (1994a) who observed that diacylglycerol is capable of inducing a voltage-dependent decrease of single channel openings in a cell-attached patch. Moreover, in their experiments, the removal of Na+ channel inactivation by means of batrachotoxin effectively prevented the diacylglycerol-dependent inhibition of macroscopic Na+ current.

The functional balance between excitation and inhibition due to PKC-dependent Na+ channel phosphorylation also depends on changes affecting the voltage dependence of INa,T and INa,P activation. According to the ‘modal gating’ hypothesis, both INa,T and INa,P are sustained by an ion flux through the same channel population, with the ‘persistent’ current flow being accounted for by the small fraction of channels escaping fast inactivation (Patlak & Ortiz 1986; Alzheimer et al. 1993; Brown et al. 1994). Our observations suggest that the OAG-induced increase in INa,P is directly due to a favoured opening in the persistent mode of a subset of still-closed channels rather than a slowing of channel inactivation. In fact, we found that the INa,T decay speed was never affected in neocortical neurones, and this finding is in line with the results of a previous study of hippocampal neurones by Cantrell et al. 1996. The increase in INa,P occurred in a range of potentials at which steady-state Na+ channel inactivation began to be enhanced in the presence of OAG, which is not surprising in the light of the basic property of INa,P of being poorly affected by conditioning potentials large enough to greatly reduce or abolish the transient current (French et al. 1990).

The presence of OAG also slightly favoured the transient opening of Na+ channels at rather negative Vm values (−45 and −35 mV), as is shown by the small hyperpolarising shift of the INa,T activation curve. It has previously been found that G-protein activation leads to a larger hyperpolarising shift of both the activation and inactivation properties of Na+ channels (Ma et al. 1994), but there are no published reports concerning PKC-dependent modulation. Our results based on macroscopic Na+ current recordings do not allow us to say whether the changes in the INa,T voltage dependence of activation are secondary to those associated with enhanced persistent channel opening but, given that INa,P represents only a very small fraction of total Na+ current, it is unlikely that the leftward shift of its activation is responsible for that of the whole sodium current. However, we can hypothesise that its consistent effect on both INa,T and INa,P activation may be due to the particular PKC-dependent phosphorylation of a single channel subset that becomes more prone to opening at rather negative Vm values in both the transient and persistent mode.

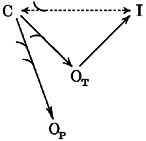

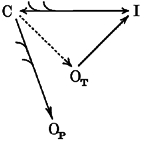

In schemes 1 and 2 we illustrate the modifications in the balance between channel states that can be hypothesised to result from PKC-dependent phosphorylation in neocortical pyramidal neurones. Scheme 1 refers to the situation of a relatively high degree of cell membrane polarisation (e.g. when neurones are at their spontaneous Vrest). The transition from a closed (C) to an inactivated (I) state is already favoured by the PKC-dependent channel phosphorylation but, at such a negative membrane potential, the large majority of channels are still closed. Due to the leftward shift of channel activation, the persistent openings (OP) in response depolarising stimuli are enhanced, and to a lesser extent, also the transient openings (OT) are favoured. The increased recruitment of channels to state I at Vrest becomes influent only with currents evoked by large depolarisations, expected to activate virtually all the channels dwelling in the closed state. Scheme 2 describes the changes presumed to occur with conditioning depolarisations. The already prominent transition of channels from a C to an I state, spontaneously occurring at these potentials, is further increased by PKC activation, such that only a small number of channels are available to open in the transient mode, whereas the openings in the persistent modality, which are much less influenced by steady-state inactivation, are unaffected.

Scheme 1.

Scheme 2.

Effects on neuronal discharges and physiopathological implications

The current-clamp data we obtained from intracellular recordings performed in slices are fully consistent with those obtained from voltage-clamp recordings made in dissociated neocortical neurones, and indicate a net excitatory effect of OAG-operated changes on Na+-dependent membrane behaviour. OAG-induced enhancement of INa,P at rather negative membrane potentials can be expected to result in a potentially important enhancement of cell excitability, by means of an augmented tendency to reach the AP discharge threshold, and an increase in the firing rate in response to low depolarising stimuli. INa,P-dependent depolarising rectification crucially affects subthreshold membrane behaviour by helping neurones to sustain repetitive individual AP discharges (Stafstrom et al. 1982, 1985; Crill, 1996) and generate burst discharges (Mattia et al. 1993; Franceschetti et al. 1995; Guatteo et al. 1996). All the expected changes due to INa,P amplification were observed in the presence of OAG. The IB neurones not only needed lower depolarising stimuli in order to discharge, but also showed an increased ability to generate low-rate repetitive bursts in response to depolarisations just above the threshold level, and the RS neurones showed an increased frequency of individual AP discharges. It must be remembered that the phosphorylation due to PKC activation not only modulates Na+ channels, but also a number of other voltage-sensitive channels (Levitan, 1994) affecting near-threshold membrane behaviour and firing. However, the substantial contribution of the positive OAG-operated modulation of INa,P in amplifying the response to low depolarising stimuli is supported by the consistent results obtained in slices perfused with a modified ACSF designed to minimise the effects of the K+ and Ca2+ currents.

Our findings in slices and dissociated pyramidal neurones are in line with the results obtained by Astman et al. 1998 in layer V neocortical slices, which indicated a hyperpolarising shift of INa,P activation capable of increasing neuronal excitability, but the results of other studies indicate that carbachol-operated PKC activation leads to negative INa,P modulation (Cantrell et al. 1996; Mittmann & Alzheimer, 1998). This discrepancy may be due to differences in neuronal populations or in the method used to activate PKC (direct PKC activators versus carbachol-induced activation). It is known that PKC-activating substances induce uneven changes in Na+ currents (Godoy & Cukierman, 1994b), which perhaps depend on their effects on different PKC isoforms. We selected medium to large pyramidal cells for our experiments performed on dissociated neurones, which presumably included a large number of layer V neurones (including IB neurones similar to those tested in the neocortical slices). This selection may have significantly affected the results because we have observed that IB neurones and a subset of RS neurones have a persistent fraction of Na+ currents that especially contributes to their firing properties and after-potentials, possibly due to the presence of channel subsets that are more prone to persistent opening (Franceschetti et al. 1995; Mantegazza et al. 1998).

It has recently been found that carbachol inhibits burst firing via PKC activation in hippocampal neurones (Alroy et al. 1999), whereas previous studies of hippocampal (Benardo & Prince, 1982) and subicular neurones (Kawasaki & Avoli, 1996) found that burst firing was enhanced, but it is difficult to compare our results in neocortical neurones with those obtained in other pyramidal neurones using different PKC-activating procedures or different stimulus protocols. We found a consistent OAG-induced amplification of bursting behaviour when the neurones were stimulated by threshold or just-suprathreshold depolarising pulses, but not when they were injected with larger suprathreshold currents, which caused the firing mode to shift from repetitive bursts to one or two initial bursts followed by individual APs, as is commonly observed in IB neurones responding to quite large depolarisations (Silva et al. 1991; Tseng & Prince, 1993; Franceschetti et al. 1998). In brief, this change in firing behaviour occurred at lower depolarising currents in the presence of OAG than those required under control conditions. These findings do not contradict the evidence of a near-rest amplification of INa,P or the assumption of increased cell excitability because the individual APs following the initial burst were superimposed to a steady depolarisation that may well correspond to an amplified contribution of the INa,P flow. Moreover, the shift from a low frequency burst to a relatively higher rhythmic AP discharge has been suggested to underlie the generation of fast cortical rhythms (Silva et al. 1991).

The expected inhibitory effect of maximal INa,T peak inhibition and the leftward shift of INa,T steady-state inactivation did not lead to any obvious decrease in cell excitability in the slice experiments. The amplitude of the individual APs was slightly reduced and their slope significantly decreased in the neurones perfused by modified ACSF containing Ca2+ and K+ blockers and moderately decreased Na+ concentrations, but only a minimal decrease in the slope of the AP rising phase could be detected in the neurones recorded in the presence of physiological extracellular Na+ concentrations. It is likely that the number of Na+ channels in intact neurones is so large that a moderate reduction in the maximal peak amplitude of INa,T does not significantly affect the characteristics of individual APs, as is commonly observed in the case of the perfusion of anti-epileptic drugs that significantly inhibit INa,T but usually have no effect on individual APs (McLean & MacDonald, 1983, 1986). Furthermore, the strong hyperpolarising after-potentials occurring in all neuronal subtypes at a rather low firing rate should efficiently relieve most of the voltage-dependent Na+ channel inactivation by minimising the effect of the PKC-dependent increase in steady inactivation and emphasising that of the enhanced INa,P.

In conclusion, our data indicate that the PKC-operated phosphorylation of Na+ channels induced by the endogenous OAG physiological activator can effectively enhance excitability in medium to large dissociated neocortical pyramidal neurones, and in layer V pyramidal neurones recorded in sensorimotor cortex slices. It has previously been reported that long-lasting PKC up-regulation occurs in ‘chronic’ epilepsy models (Chen et al. 1992; Osonoe et al. 1994; Akiyama et al. 1995), possibly as a result of plastic cell changes in response to repeated epileptic events. This modulation may sustain an up-regulation of INa,P, thus increasing the probability of reaching the discharge threshold of the neurones, or directly contributing towards shaping the epileptic events themselves (as in the case of cell models of hyperexcitability; Segal & Douglas, 1997).

Acknowledgments

The study has been supported by the Italian Ministry of Health and by R. A. W. Johnson Pharmaceutical Research Institute.

References

- Akiyama K, Ono M, Kohira I, Daigen A, Ishihara T, Kuroda S. Long-lasting increase in protein kinase C activity in the hippocampus of amygdala kindled rat. Brain Research. 1995;679:212–230. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00221-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alroy G, Su H, Yaari Y. Protein kinase C mediates muscarinic block of intrinsic bursting in rat hippocampal neurons. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;518:71–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0071r.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer C. A novel voltage-dependent cation current in rat neocortical neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;479:199–205. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer C, Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Modal gating of Na+ channels as a mechanism of persistent Na+ current in pyramidal neurons from rat and cat sensorimotor cortex. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:660–673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00660.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astman N, Gutnick MJ, Fleidervish IA. Activation of protein kinase C increases neuronal excitability by regulating persistent Na+ current in mouse neocortical slices. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;80:1547–1551. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.3.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azouz R, Jensen MS, Yaary Y. Ionic basis of spike after-depolarization and burst generation in adult rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;492:211–223. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benardo LS, Prince DA. Cholinergic excitation of mammalian hippocampal pyramidal cells. Brain Research. 1982;249:315–331. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett PB, Yazawa K, Makita N, George A. Molecular mechanism for an inherited cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 1995;376:683–685. doi: 10.1038/376683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff U, Werner V, Safronov BV. Na+-activated K+ channels in small dorsal root ganglion neurones of rat. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;510:743–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.743bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AM, Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Different voltage dependence of transient and persistent Na+ currents is compatible with modal-gating hypothesis for sodium channels. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;71:2562–2565. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.6.2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon SC. Ion-channel defects and aberrant excitability in myotonia and periodic paralysis. Trends in Neurosciences. 1996;19:3–10. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)81859-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell AR, Ma JY, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Muscarinic modulation of sodium current by activation of protein kinase C in rat hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1996;16:1019–1026. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cathala L, Paupardin-Tritsch D. Neurotensin inhibition of the hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) in the rat substantia nigra pars compacta implicates the protein kinase C pathway. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;503:87–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.087bi.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. Cellular and molecular biology of voltage-gated sodium channels. Physiological Reviews. 1992;72:S15–47. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.suppl_4.S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SJ, Desai MA, Klann E, Winder DG, Sweatt JD, Conn PJ. Amygdala kindling alters protein kinase C activity in dentate gyrus. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1992;59:1761–1769. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb11008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crill WE. Persistent sodium current in mammalian central neurons. Annual Review of Physiology. 1996;58:349–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukierman S. Regulation of voltage-dependent sodium channels. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1996;151:203–214. doi: 10.1007/s002329900071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascal N, Lotan I. Activation of protein kinase C alters voltage dependence of a Na+ channel 1991. Neuron. 1991;6:165–175. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90131-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschetti S, Guatteo E, Panzica F, Sancini G, Wanke E, Avanzini G. Ionic mechanisms underlying burst firing in pyramidal neurons: intracellular study in rat sensorimotor cortex. Brain Research. 1995;69:6127–6139. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00807-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschetti S, Sancini G, Panzica F, Radici C, Avanzini G. Postnatal differentiation of firing properties and morphological characteristics in layer V pyramidal neurons of the sensorimotor cortex. Neuroscience. 1998;83:1013–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00463-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French CR, Sah P, Buckett KJ, Gage PW. A voltage-dependent persistent sodium current in mammalian hippocampal neurons. Journal of General Physiology. 1990;95:1139–1157. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.6.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy CMG, Cukierman S. Diacylglycerol-induced activation of protein kinase C attenuates Na+ currents by enhancing inactivation from the closed state. Pflügers Archiv. 1994a;429:245–252. doi: 10.1007/BF00374319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy CMG, Cukierman S. Multiple effect of protein kinase C activators on Na+ currents in mouse neuroblastoma cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1994b;140:101–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00232898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guatteo E, Franceschetti S, Bacci A, Avanzini G, Wanke E. A TTX-sensitive conductance underlying burst firing in isolated pyramidal neurons from rat neocortex. Brain Research. 1996;741:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00866-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor R, Li YG, Smith KJ. Slow sodium-dependent potential oscillations contribute to ectopic firing in mammalian demyelinated axons. Brain. 1997;120:647–652. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.4.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, Avoli M. Excitatory effect induced by carbachol on bursting neurons of rat subiculum. Neuroscience Letters. 1996;15:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan JB. Modulation of ion channels by protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Annual Review of Physiology. 1994;56:193–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, West JW, Lai Y, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Functional modulation of brain Na+ channels by cAMP-dependent phosphorylation. Neuron. 1992;8:1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90135-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YJ, Li M, Catterall WA, Scheuer T. Modulation of brain Na+ channels by a G protein coupled pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:12351–12355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean MJ, MacDonald RL. Multiple action of phenytoin on mouse spinal cord neurones. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1983;227:779–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean MJ, MacDonald RL. Sodium valproate, but not ethosuximide, produces use-dependent and voltage-dependent limitation of high frequency repetitive firing of action potentials of mouse central neurons in cell culture. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1986;237:1001–1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti J, Alonso A. Biophysical properties and slow voltage-dependent inactivation of a sustained sodium current in entorhinal cortex layer-II principal neurons. A whole-cell and single-channel study. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;114:491–509. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantegazza M, Franceschetti S, Avanzini G. Anemone toxin (ATX II)-induced increase in persistent sodium current: effects on the firing properties of rat neocortical pyramidal neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:105–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.105bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattia D, Hwa GGC, Avoli M. Membrane properties of rat subicular neuronesin vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;70:1244–1248. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.3.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittmann T, Alzheimer C. Muscarinic inhibition of persistent Na+ current in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;79:1579–1582. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.3.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittmann T, Linton SM, Schwindt P, Crill W. Evidence for persistent Na+ current in apical dendrites of rat neocortical neurons from imaging of Na+-sensitive dye. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;78:1188–1192. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.2.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numann R, Catterall WA, Scheuer T. Functional modulation of brain sodium channel by protein kinase C phosphorylation. Science. 1991;254:115–118. doi: 10.1126/science.1656525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly JP, Cummins TR, Haddad GG. Oxygen deprivation inhibits Na+ current in rat hippocampal neurones via protein kinase C. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;503:479–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.479bg.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osonoe K, Ogata S, Iwata Y, Mori N. Kindled amygdaloid seizures in rats cause immediate and transient increase in protein kinase activity followed by transient suppression of the activity. Epilepsia. 1994;35:850–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patlak JB, Ortiz M. Two modes of gating during late Na+ channel currents in frog sartorius muscle. Journal of General Physiology. 1986;87:305–326. doi: 10.1085/jgp.87.2.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Amplification of synaptic current by persistent sodium conductance in apical dendrites of neocortical neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;74:2220–2224. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.5.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal MM. Endogenous bursts underlie seizure-like activity in solitary excitatory hippocampal neurons in microcultures. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;72:1874–1884. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal MM, Douglas AF. Late sodium channel openings underlying epileptiform activity are preferentially diminished by the anticonvulsant phenytoin. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;77:3021–3034. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.6.3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selyanko AA, Sim JA. Ca2+-inhibited non-inactivating K+ channels in cultured rat hippocampal pyramidal neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;510:71–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.071bz.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva LR, Amitai Y, Connors BW. Intrinsic oscillations of neocortex generated by layer 5 pyramidal neurons. Science. 1991;251:432–435. doi: 10.1126/science.1824881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafstrom CE, Schwindt PC, Chubb MC, Crill WE. Properties of persistent sodium conductance and calcium conductance of layer V neurons from cat sensorimotor cortexin vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1985;53:153–170. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafstrom CE, Schwindt PC, Crill WA. Negative slope conductance due to a persistent subthreshold sodium current in cat neocortical neuronsin vitro. Brain Research. 1982;236:221–226. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GJ, Sakmann B. Active propagation of somatic action potentials into neocortical pyramidal cell dendrites. Nature. 1994;367:69–72. doi: 10.1038/367069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng GF, Prince DA. Heterogeneity of rat corticospinal neurons. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993;335:92–108. doi: 10.1002/cne.903350107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West JW, Numann R, Murphy BJ, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. A phosphorylation site in the Na+ channel required for modulation by protein kinase C. Science. 1991;254:866–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1658937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]