Abstract

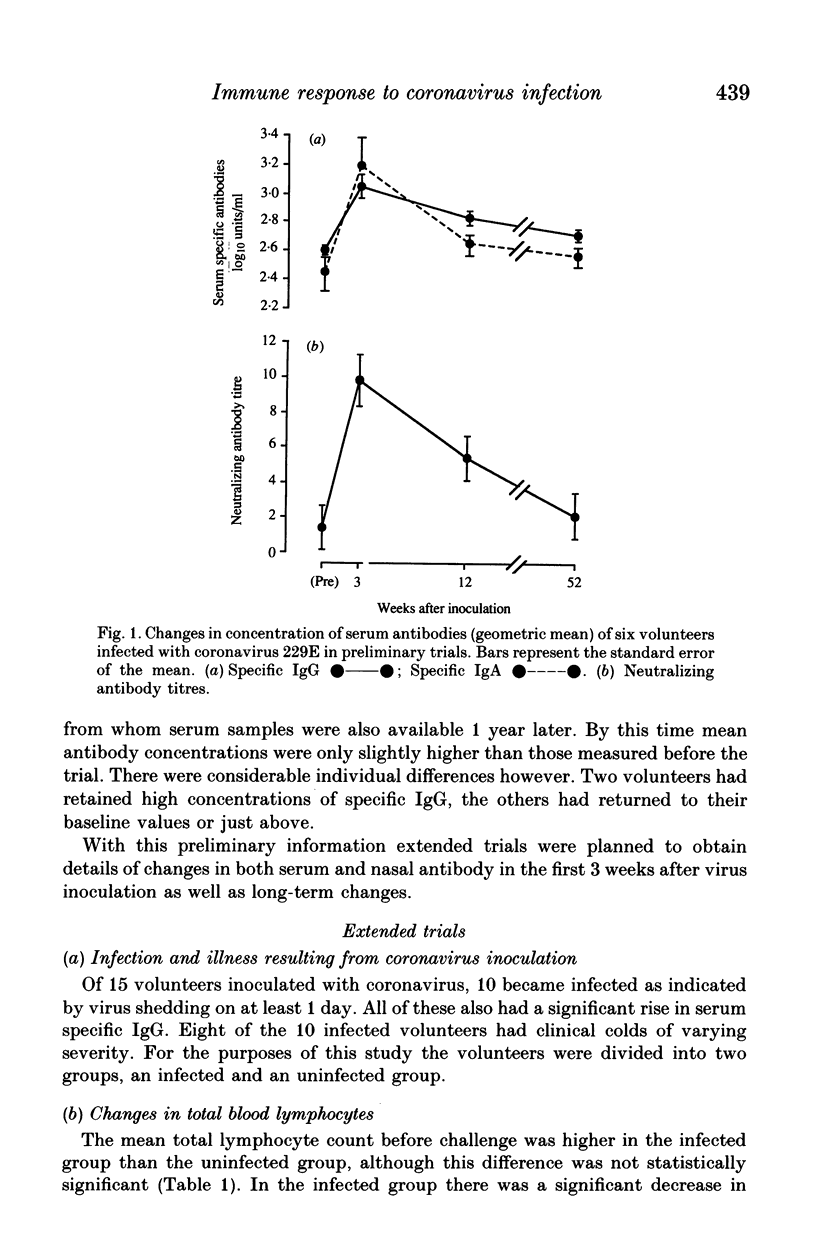

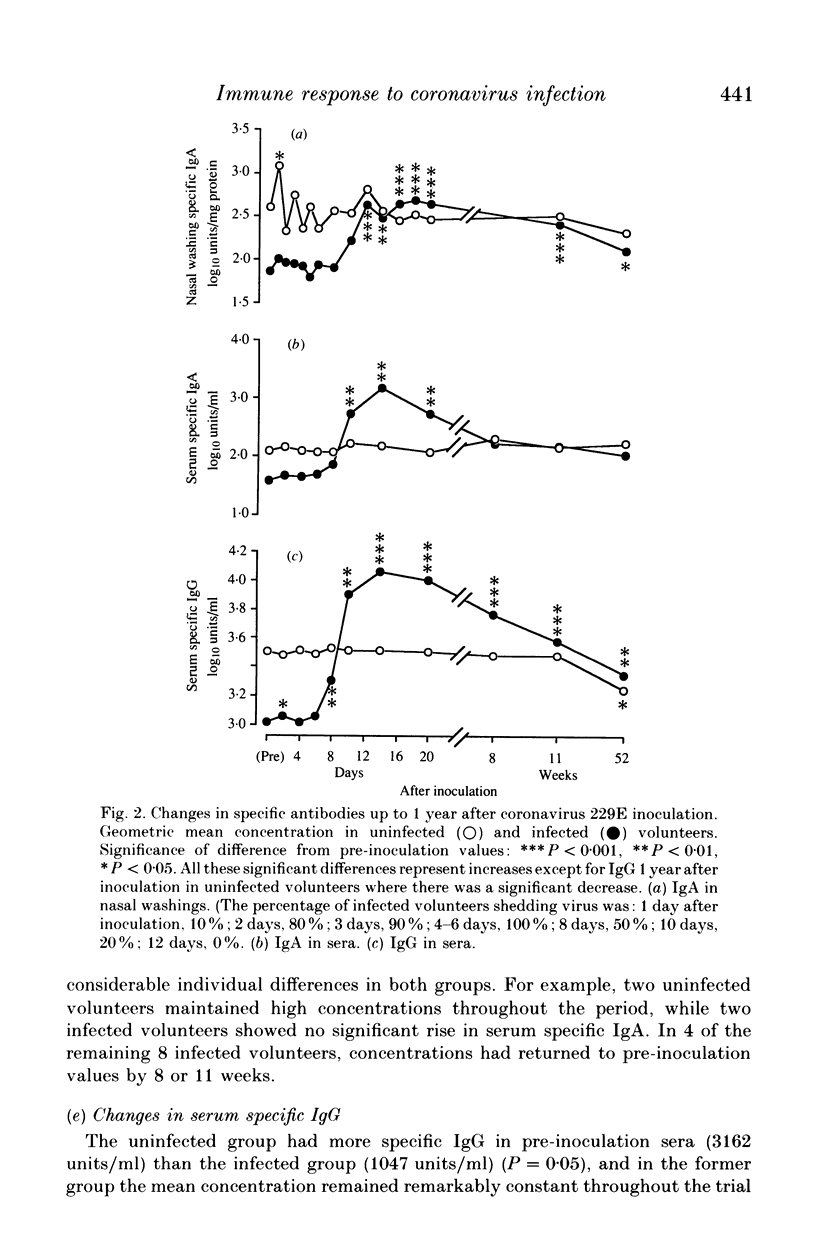

After preliminary trials, the detailed changes in the concentration of specific circulating and local antibodies were followed in 15 volunteers inoculated with coronavirus 229E. Ten of them, who had significantly lower concentrations of pre-existing antibody than the rest, became infected and eight of these developed colds. A limited investigation of circulating lymphocyte populations showed some lymphocytopenia in infected volunteers. In this group, antibody concentrations started to increase 1 week after inoculation and reached a maximum about 1 week later. Thereafter antibody titres slowly declined. Although concentrations were still slightly raised 1 year later, this did not always prevent reinfection when volunteers were then challenged with the homologous virus. However, the period of virus shedding was shorter than before and none developed a cold. All of the uninfected group were infected on re-challenge although they also appeared to show some resistance to disease and in the extent of infection. These results are discussed with reference to natural infections with coronavirus and with other infections, such as rhinovirus infections.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aoki F. Y., Stiver H. G., Sitar D. S., Hammond G. W., Milley E. V., Vermeersch C., Hughes H. E., Cooper T., Sekla L., Lamontage M. Potential of influenza vaccine and amantadine to prevent influenza A illness in Canadian forces personnel 1980-1983. Mil Med. 1986 Sep;151(9):459–465. doi: 10.1093/milmed/151.9.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay W. S., Callow K. A., Sergeant M., al-Nakib W. Evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay that measures rhinovirus-specific antibodies in human sera and nasal secretions. J Med Virol. 1988 Aug;25(4):475–482. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890250411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay W. S., al-Nakib W., Higgins P. G., Tyrrell D. A. The time course of the humoral immune response to rhinovirus infection. Epidemiol Infect. 1989 Dec;103(3):659–669. doi: 10.1017/s095026880003106x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent D. E., Broadbent M. H., Phillpotts R. J., Wallace J. Some further studies on the prediction of experimental colds in volunteers by psychological factors. J Psychosom Res. 1984;28(6):511–523. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(84)90085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscho R. F., Perkins J. C., Knopf H. L., Kapikian A. Z., Chanock R. M. Further characterization of the local respiratory tract antibody response induced by intranasal instillation of inactivated rhinovirus 13 vaccine. J Immunol. 1972 Jan;108(1):169–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler W. T., Waldmann T. A., Rossen R. D., Douglas R. G., Jr, Couch R. B. Changes in IgA and IgG concentrations in nasal secretions prior to the appearance of antibody during viral respiratory infection in man. J Immunol. 1970 Sep;105(3):584–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callow K. A. Effect of specific humoral immunity and some non-specific factors on resistance of volunteers to respiratory coronavirus infection. J Hyg (Lond) 1985 Aug;95(1):173–189. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400062410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cate T. R., Rossen R. D., Douglas R. G., Jr, Butler W. T., Couch R. B. The role of nasal secretion and serum antibody in the rhinovirus common cold. Am J Epidemiol. 1966 Sep;84(2):352–363. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro J. J., Monto A. S. Community-wide outbreak of infection with a 229E-like coronavirus in Tecumseh, Michigan. J Infect Dis. 1970 Oct;122(4):272–279. doi: 10.1093/infdis/122.4.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crifö S., Vella S., Filiaci F., Resta S., Rocchi G. Secretory immune response after nasal vaccination with live attenuated influenza viruses. Rhinology. 1980 Jun;18(2):87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolin R., Richman D. D., Murphy B. R., Fauci A. S. Cell-mediated immune responses in humans after induced infection with influenza A virus. J Infect Dis. 1977 May;135(5):714–719. doi: 10.1093/infdis/135.5.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faguet G. B. The effect of killed influenza virus vaccine on the kinetics of normal human lymphocytes. J Infect Dis. 1981 Feb;143(2):252–258. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins P. G., Phillpotts R. J., Scott G. M., Wallace J., Bernhardt L. L., Tyrrell D. A. Intranasal interferon as protection against experimental respiratory coronavirus infection in volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983 Nov;24(5):713–715. doi: 10.1128/aac.24.5.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes M. J., Callow K. A., Parry H. F. An improved method for recovery of secretory immunoglobulins and lymphocytes from the nasal mucosa. J Immunol Methods. 1987 Apr 16;98(2):183–187. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(87)90003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes M. J., Reed S. E., Stott E. J., Tyrrell D. A. Studies of experimental rhinovirus type 2 infections in polar isolation and in England. J Hyg (Lond) 1976 Jun;76(3):379–393. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400055303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye H. S., Marsh H. B., Dowdle W. R. Seroepidemiologic survey of coronavirus (strain OC 43) related infections in a children's population. Am J Epidemiol. 1971 Jul;94(1):43–49. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIDWELL O. M., WILLIAMS R. E. The epidemiology of the common cold. I. J Hyg (Lond) 1961 Sep;59:309–319. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400038973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson H. E., Reed S. E., Tyrrell D. A. Isolation of rhinoviruses and coronaviruses from 38 colds in adults. J Med Virol. 1980;5(3):221–229. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890050306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levandowski R. A., Ou D. W., Jackson G. G. Acute-phase decrease of T lymphocyte subsets in rhinovirus infection. J Infect Dis. 1986 Apr;153(4):743–748. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macnaughton M. R. Occurrence and frequency of coronavirus infections in humans as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Infect Immun. 1982 Nov;38(2):419–423. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.2.419-423.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monto A. S. Medical reviews. Coronaviruses. Yale J Biol Med. 1974 Dec;47(4):234–251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillpotts R. J. Clones of MRC-C cells may be superior to the parent line for the culture of 229E-like strains of human respiratory coronavirus. J Virol Methods. 1983 May;6(5):267–269. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(83)90041-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed S. E. The behaviour of recent isolates of human respiratory coronavirus in vitro and in volunteers: evidence of heterogeneity among 229E-related strains. J Med Virol. 1984;13(2):179–192. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890130208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossen R. D., Butler W. T., Cate T. R., Szwed C. F., Couch R. B. Protein composition of nasal secretion during respiratory virus infection. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1965 Aug-Sep;119(4):1169–1176. doi: 10.3181/00379727-119-30406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossen R. D., Butler W. T., Waldman R. H., Alford R. H., Hornick R. B., Togo Y., Kasel J. A. The proteins in nasal secretion. II. A longitudinal study of IgA and neutralizing antibody levels in nasal washings from men infected with influenza virus. JAMA. 1970 Feb 16;211(7):1157–1161. doi: 10.1001/jama.211.7.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinberg M., Blacklow N. R., Goldstein A. L., Parrino T. A., Rose F. B., Cathcart E. S. Influenza: response of T-cell lymphopenia to thymosin. N Engl J Med. 1976 May 27;294(22):1208–1211. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197605272942204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totman R., Kiff J., Reed S. E., Craig J. W. Predicting experimental colds in volunteers from different measures of recent life stress. J Psychosom Res. 1980;24(3-4):155–163. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(80)90037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagihara R., McIntosh K. Secretory immunological response in infants and children to parainfluenza virus types 1 and 2. Infect Immun. 1980 Oct;30(1):23–28. doi: 10.1128/iai.30.1.23-28.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]