Abstract

The G protein-coupled μ-opioid receptor (μOR) mediates the physiological effects of endogenous opioid peptides as well as the structurally distinct opioid alkaloids morphine and etorphine. An intriguing feature of μOR signaling is the differential receptor trafficking and desensitization properties following activation by distinct agonists, which have been proposed as possible mechanisms related to opioid tolerance. Here we report that the ability of distinct opioid agonists to differentially regulate μOR internalization and desensitization is related to their ability to promote G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK)-dependent phosphorylation of the μOR. Although both etorphine and morphine effectively activate the μOR, only etorphine elicits robust μOR phosphorylation followed by plasma membrane translocation of β-arrestin and dynamin-dependent receptor internalization. In contrast, corresponding to its inability to cause μOR internalization, morphine is unable to either elicit μOR phosphorylation or stimulate β-arrestin translocation. However, upon the overexpression of GRK2, morphine gains the capacity to induce μOR phosphorylation, accompanied by the rescue of β-arrestin translocation and receptor sequestration. Moreover, overexpression of GRK2 also leads to an attenuation of morphine-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase. These findings point to the existence of marked differences in the ability of different opioid agonists to promote μOR phosphorylation by GRK. These differences may provide the molecular basis underlying the different analgesic properties of opioid agonists and contribute to the distinct ability of various opioids to induce drug tolerance.

Opioid alkaloids are among the most potent analgesics used clinically (1). Opioid alkaloids, as well as endogenous opioid peptides, exert their multiple biological effects on target tissues through interacting with cell surface receptors including the δ-, μ-, and κ-opioid receptors (2–5). All three opioid receptor subtypes belong to the family of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and, when expressed in cell lines, mediate the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity by opioids (2–5). Chronic administration of opioids has been associated with drug tolerance and dependence, processes that are intimately related to opioid addiction (5–7). The μ-opioid receptor (μOR) serves as the principle physiological target for most clinically important opioid analgesics, including those with high addiction liability such as morphine and fentanyl (5, 6). Although many opioid alkaloids exert their pharmacological effects via the μOR, their binding affinities for the μOR and potencies to activate the receptor do not always correspond to their ability to induce tolerance. This suggests that other cellular processes that modulate μOR responsiveness, such as receptor desensitization and internalization (i.e., sequestration), may contribute to opioid tolerance and dependence (5–12).

Like many other GPCRs, the opioid receptors are regulated by agonist-dependent processes and undergo receptor phosphorylation, desensitization, internalization, and downregulation (8–16). Interestingly, in addition to the subtype-specific regulation of different opioid receptors (11, 16–18), individual opioid receptors are differentially regulated by distinct opioid agonists (8–10, 12, 15, 19–21). In the case of the μOR, opioid agonists that demonstrate equivalent abilities to activate μOR signaling exhibit remarkable differences in their ability to functionally desensitize the μOR (10, 12) and induce μOR internalization both in transfected cells and in neurons (8, 9, 15, 19, 20). Thus, although etorphine and various other opioid peptides elicit rapid μOR desensitization and internalization, morphine, the prototypic opioid analgesic, fails to elicit μOR sequestration. However, the detailed molecular events underlying this differential regulation of the μOR by distinct agonists remain unclear.

Studies on the regulation of the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) have identified G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) and arrestin proteins as the crucial molecular determinants governing receptor desensitization and resensitization (22–26). This molecular scheme has now been extended to other GPCRs and probably represents a common regulatory scenario for members of the GPCR superfamily (27–30). In the case of the β2AR, GRKs specifically phosphorylate and uncouple the agonist-activated receptors and facilitate their interaction with β-arrestins (22, 23). β-arrestins, when bound, not only serve to further uncouple the receptors from their cognate heterotrimeric G proteins (23) but play an important role in initiating receptor sequestration and resensitization (22, 24–26, 31, 32). Intriguingly, in rat locus coeruleus, a region rich in μORs, levels of GRK2 and β-arrestin expression are elevated as a result of chronic morphine administration (33). Moreover, coexpression of GRK3 and β-arrestin2 in Xenopus oocytes results in an attenuation of μOR-activated potassium conductance (11). These findings suggest that GRK and β-arrestin might play a role in the functional modulation of μOR signaling.

In this study, we explored whether GRK-mediated phosphorylation and β-arrestin interaction represent the molecular mechanisms underlying μOR desensitization and sequestration. Our findings reveal that GRKs play a pivotal role in the regulation of μOR function. Moreover, we show that the observed differences in the ability of distinct opioid agonists to promote μOR sequestration are related to their ability to induce GRK-mediated phosphorylation of the receptor. The inability of morphine to stimulate the intracellular trafficking of the μOR was overcome following overexpression of GRK2, suggesting that the specific pattern of μOR regulation may be dependent on the cell- and/or tissue-specific complement of GRK proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA Construction and Cell Culture.

The human influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) epitope-tagged μOR was constructed by using oligonucleotides and PCR to add 13 amino acids (YPYDVPDYALVPR) to the amino terminus of the rat μ-opioid receptor (34). The construction of plasmids containing cDNAs for GRK2, GRK2-K220M, β-arrestin1, β-arrestin1-V53D, dynamin I, dynamin I-K44A, and β-arrestin2 green fluorescent protein conjugate (βarr2/GFP) was described previously (24, 25, 31, 35). HEK 293 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were grown in Eagle’s minimal essential medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10% vol/vol) (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA). The cells were transiently transfected with a modified calcium phosphate method as described (36). The μOR expression was measured by flow cytometry and normalized according to the β2AR expression measured at the same time by both flow cytometry and saturating binding studies (25). The level of μOR expression was between 4,000 and 6,000 fmol/mg whole cell protein for the experiments with a confocal microscope (see below) and between 1,500 and 2,000 fmol/mg whole cell protein for all other experiments.

μOR Sequestration.

Sequestration of HA-tagged μOR was measured by flow cytometry as described (31). Sequestration was defined as the fraction of total cell surface receptors that are removed from the plasma membrane after exposure to agonist and thus are not accessible to antibodies from outside the cell. The cells were exposed to 500 nM etorphine or 10 μM morphine at 37°C for 1 hr before antibody staining.

Whole Cell Receptor Phosphorylation.

Receptor phosphorylation was carried out as previously described (25, 26). Briefly, cells were grown in six-well dishes and labeled with [32P]orthophosphate (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA). Cells were then treated with or without 500 nM etorphine or 10 μM morphine for 10 min at 37°C, washed with PBS, and solubilized in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl/50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4/5 mM EDTA/10 mM NaF/10 mM disodium pyrophosphate/1% Nonidet P-40/0.5% deoxycholate/0.1% SDS). HA-tagged μORs were immunoprecipitated with 12CA5 antibody (Boehringer Mannheim) as described, and were subjected to SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography. An equivalent amount of receptor protein was loaded in each well as judged by μOR expression and the amount of solubilized protein in each lysate. The extent of receptor phosphorylation was analyzed by using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImaging system and imagequant software.

Confocal Microscopy.

Confocal microscopy was performed on a Zeiss LSM-410 laser scanning microscope by using a 40 × 1.2NA water immersion lens. HEK 293 cells were transfected to overexpress μOR and low levels of βarr2/GFP with or without GRK2 or GRK2-K220M, and were plated on 35-mm glass-bottomed culture dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA) and warmed to 30°C in culture medium with 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.3) on a heated microscope stage. βarr2/GFP fluorescence was collected sequentially by using the Zeiss LSM software time scan function using single line excitation (488 nm). Etorphine (500 nM) or morphine (10 μM) was applied to the cells during the scanning.

Whole Cell Adenylyl Cyclase Assay.

Cells were grown in twelve-well dishes, labeled overnight with 1 μCi/ml per well (1 Ci = 37 GBq) of [3H]adenine (NEN Life Science Products), and then washed with fresh serum-free medium. For measuring the dose response of morphine-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity, cells were treated with 1 μM forskolin (Sigma) alone (control) or with 1 μM forskolin and varying concentrations of morphine in medium containing 10 mM Hepes and 1 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine at pH 7.4 for 15 min at 37°C. For assessing the time course of morphine-mediated inhibition of cyclase response, cells were treated with 1 μM forskolin in the absence (control) or presence of 10 μM morphine for varying time periods at 37°C. The medium was aspirated, and 1 ml of ice-cold stop solution (2.5% vol/vol perchloric acid, 0.1 mM cAMP, and 2 μCi [14C]cAMP per 500 ml) was added to each well followed by incubation on ice for 20–30 min. The cell lysate was added to tubes containing 100 μl of 4.2 M KOH and the cAMP accumulated in the cells was quantitated chromatographically by the method of Salomon (37).

Data Analysis.

The mean and standard error of the mean are expressed for values obtained from the number of separate experiments indicated. Dose response and time course data were analyzed by using graphpad prism. Statistical analysis of adenylyl cyclase inhibition curves was performed by a two-way ANOVA combined with a contrast matrix. In all other cases, statistical significance was determined by an unpaired two-tailed t test.

RESULTS

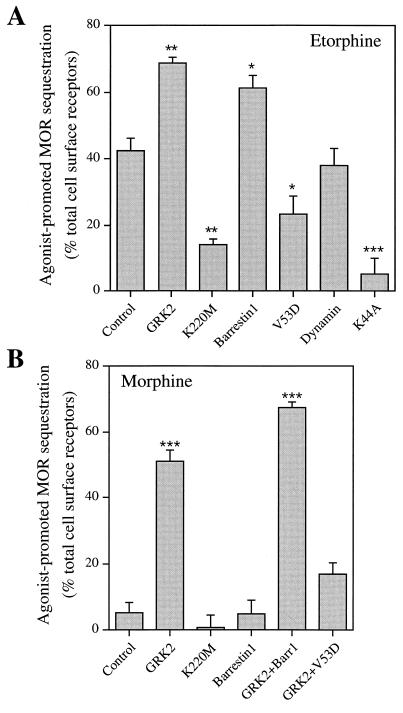

Initial experiments explored the possible regulatory role of GRKs and β-arrestins in μOR endocytosis. When transiently expressed in HEK 293 cells, quantitation by flow cytometry indicated that 42 ± 4% of total cell surface receptors were internalized in response to 1 hr agonist stimulation with etorphine (Fig. 1A). Overexpression of wild-type GRK2 or β-arrestin1 enhanced further the magnitude of etorphine-mediated μOR sequestration to 69 ± 2% and 61 ± 4%. In contrast, dominant negative mutants GRK2-K220M and β-arrestin1-V53D previously shown to block β2AR internalization (24, 25), reduced μOR sequestration to 14 ± 2% and 24 ± 5%, respectively (Fig. 1A). Moreover, μOR sequestration was inhibited by as much as 88 ± 11% (Fig. 1A) following the coexpression of dynamin I-K44A, which we have used previously to block clathrin-mediated endocytosis of the β2AR (31). These results indicate that etorphine-promoted μOR sequestration follows the same β-arrestin- and clathrin-coated vesicle-mediated endocytic pathway used by the β2AR.

Figure 1.

Agonist-mediated internalization of the μ-opioid receptor. (A) Effect of wild-type and mutant GRK2, β-arrestin1, or dynamin I on etorphine-promoted internalization of the μOR. (B) Effect of wild-type and mutant GRK2 and/or β-arrestin1 on morphine-promoted internalization of the μOR. HEK 293 cells were transiently transfected with plasmids containing cDNAs for HA epitope-tagged μOR together with empty vector (Control) or various other DNA constructs as indicated. Data represent mean ± SE of three to five independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001 vs. control μOR sequestration.

Although both etorphine and morphine effectively activate the μOR, morphine fails to stimulate μOR sequestration (8, 9, 15) (Fig. 1B). Therefore, because etorphine-mediated μOR sequestration was β-arrestin-dependent, we hypothesized that morphine activation of the μOR might not lead to GRK-mediated receptor phosphorylation and/or β-arrestin binding. Similar to previous reports (8, 9, 15), no apparent morphine-mediated μOR internalization was observed in HEK 293 cells (5 ± 3%) in the absence of GRK or β-arrestin overexpression. However, upon coexpression of wild-type GRK2, but not GRK2-K220M, 51 ± 3% of cell surface μORs were internalized in response to morphine treatment (Fig. 1B). Unexpectedly, even though overexpressing β-arrestin1 enhanced the effect of GRK2 on μOR sequestration (67 ± 2%), in the absence of GRK2 overexpression, β-arrestin1 overexpression alone had no rescuing effect on morphine-induced μOR sequestration (5 ± 4%) (Fig. 1B). Nevertheless, the GRK2-induced increase in μOR sequestration in response to morphine was β-arrestin-dependent, because the sequestration dominant negative mutant β-arrestin1-V53D inhibited the rescuing effect of GRK2 (Fig. 1B). The inability of β-arrestin alone to rescue μOR sequestration in response to morphine indicate that GRK-mediated phosphorylation is a prerequisite for μOR interaction with β-arrestin and therefore plays a central role in the intracellular trafficking of this opioid receptor subtype.

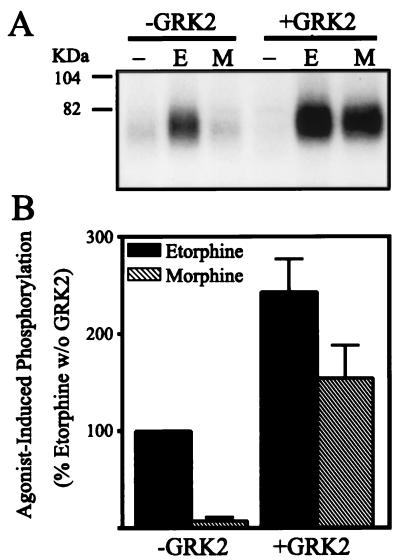

To determine whether the GRK2-induced changes in μOR internalization were associated with changes in the phosphorylation status of the receptor, we assessed the whole cell μOR phosphorylation in response to both etorphine and morphine in the presence and absence of overexpressed GRK2 in HEK 293 cells. In the absence of GRK overexpression, etorphine, but not morphine, induced a marked increase of μOR phosphorylation above basal (Fig. 2). However, overexpression of GRK2 not only increased etorphine-induced phosphorylation of the μOR to 243 ± 34% of the control levels, but also established the ability of morphine to induce μOR phosphorylation (Fig. 2). GRK overexpression increased morphine-induced phosphorylation of the μOR from 8 ± 3% to 154 ± 33% of etorphine-mediated μOR phosphorylation (Fig. 2B). These data indicate that the effects of GRK2 overexpression on μOR sequestration are at the level of the receptor but not some other cellular elements.

Figure 2.

Differential phosphorylation of the μ-opioid receptor in response to etorphine and morphine in the absence or presence of overexpressing GRK2. HA epitope-tagged μORs were transiently expressed in HEK 293 cells together with or without cotransfected GRK2. The cells were then treated with serum-free medium (−) or medium containing agonists etorphine (E) or morphine (M) as described. (A) Autoradiograph from a representative experiment showing the whole cell phosphorylation of the μOR in HEK 293 cells in the absence and presence of overexpressing GRK2 in response to etorphine (E) and morphine (M). (B) Mean ± SE of three independent experiments quantified by PhosphorImager analysis. Data were normalized to the etorphine-induced μOR phosphorylation in the absence of GRK2. Morphine-induced μOR phosphorylation in the absence of GRK2 is significantly different from etorphine-induced μOR phosphorylation without GRK2 (P < 0.001), as well as morphine-induced μOR phosphorylation in the presence of GRK2 (P < 0.05).

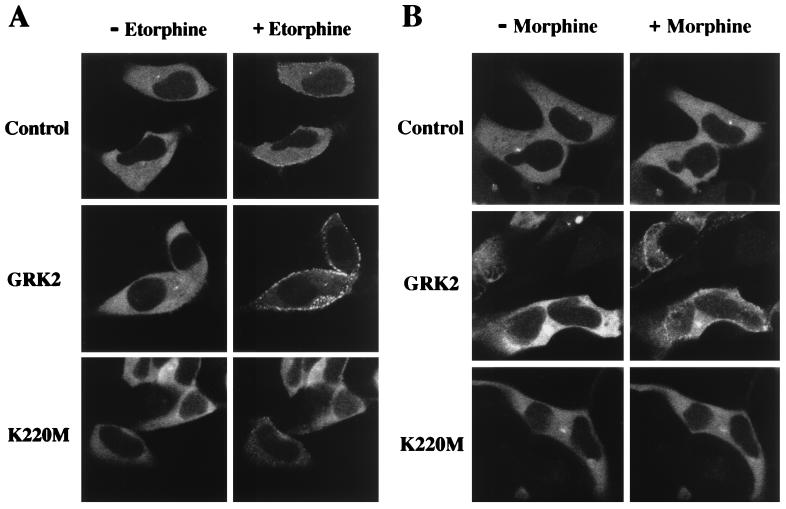

Data obtained in studying the β2AR have indicated that GRK-mediated phosphorylation is facilitory rather than mandatory for receptor sequestration (22, 24, 25), because β-arrestins exhibit the capacity to interact with β2ARs lacking sites for GRK-mediated phosphorylation (24). In contrast, β-arrestin interactions with the μOR appear exquisitely dependent on GRK-mediated phosphorylation. To investigate whether GRK-mediated phosphorylation promotes β-arrestin interactions with the μOR, we used a recently developed molecular tool, βarr2/GFP (35). The βarr2/GFP fusion protein is fully functional and has been used previously to study β-arrestin interactions with the β2AR in live cells and in real time by confocal microscopy (35). In the absence of receptor activation, βarr2/GFP was evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm of HEK 293 cells coexpressing μORs (Fig. 3). Upon exposure of the same cells to etorphine (Fig. 3A, Control) but not morphine (Fig. 3B, Control), a rapid translocation of βarr2/GFP (t1/2 ≈ 5 min) from the cytosol to a punctated membrane localization was observed. The punctated pattern of βarr2/GFP fluorescence at the plasma membrane reflects its localization with the receptor in clathrin-coated pits, as documented with the β2AR (S.S.G.F., L.S.B., J.Z., and M.G.C., unpublished data). Overexpression of GRK2 both accelerated the rate (t1/2 ≈ 2 min) and increased the magnitude of etorphine-mediated βarr2/GFP translocation as evidenced by a clearance of cytoplasmic βarr2/GFP fluorescence (Fig. 3A, GRK2). Moreover, GRK2 overexpression established the ability of morphine to induce βarr2/GFP translocation (Fig. 3B, GRK2). In contrast, overexpression of the mutant GRK2-K220M blocked etorphine-mediated βarr2/GFP translocation (Fig. 3A, K220M). These visual data indicate that GRK-dependent phosphorylation of the μOR is essential for the interaction of this receptor with β-arrestin, which when bound mediates receptor endocytosis via clathrin-coated pits.

Figure 3.

Differential βarr2/GFP translocation in response to μOR activation by etorphine (A) or morphine (B) in the absence and presence of overexpressing GRK2 or GRK-K220M. HEK 293 cells were transiently transfected to express βarr2/GFP and μOR together with or without (Control) GRK2 or GRK2-K220M. Experiments were done on a heated microscope stage set at 30°C. Shown are representative confocal microscopic images of βarr2/GFP fluorescence obtained before (− Etorphine, − Morphine) and 10 min following the addition of etorphine (+ Etorphine) or morphine (+ Morphine) to the medium. Experiments were performed independently on three to five different occasions and each time four to six cells from independent stimulation by each agonist were recorded.

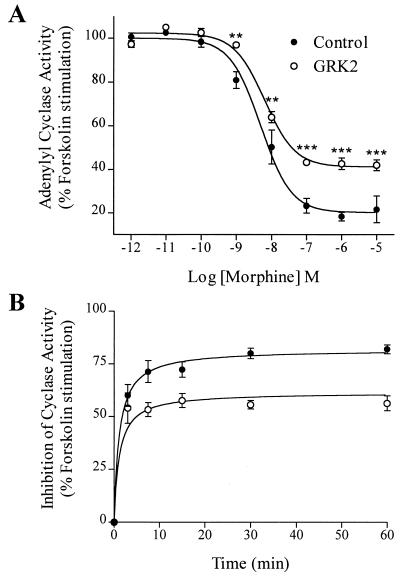

The increase in morphine-induced phosphorylation of the μOR following GRK2 overexpression was also paralleled by increased μOR desensitization (Fig. 4). In the absence of GRK2 overexpression, morphine, although unable to trigger μOR phosphorylation and internalization, is a potent inhibitor of forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity (80 ± 3% inhibition, IC50 = 4.9 ± 1.3 nM) in cells transfected to express μORs. GRK2 overexpression attenuated morphine-stimulated μOR-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase by 26 ± 1% without affecting the IC50 (6.4 ± 1.2 nM) (Fig. 4A). The observed GRK2-mediated desensitization of morphine-stimulated inhibition of cyclase activity was persistent throughout a time course for as long as 1 hr (Fig. 4B). Similar results were obtained by using etorphine, which caused an 80 ± 2% inhibition of forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity with an IC50 = 50 ± 15 pM in the absence of GRK2 overexpression, and a 57 ± 2% maximal cyclase inhibition with an IC50 of 83 ± 21 pM in the presence of overexpressing GRK2. These data support the notion that the ability of distinct opioid agonists to activate the μOR can be dissociated from their ability to trigger receptor desensitization and internalization.

Figure 4.

Effect of overexpressing GRK2 on μOR-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity by morphine. HEK 293 cells were transiently transfected to express μOR and adenylyl cyclase type V in the absence (•, control) or presence (○) of GRK2. Whole cell adenylyl cyclase activity was measured as described. (A) Dose-dependent inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity by morphine. (B) Time course of morphine-induced inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity. The results were normalized to the forskolin-stimulated cellular cyclase response. Data shown represent means ± SE of three independent experiments analyzed by graphpad prism software. **, P < 0.01 and ***, P < 0.001 vs. matched adenylyl cyclase activity in the absence of GRK2.

DISCUSSION

This study reveals the molecular basis for the observed agonist-specific regulation of μOR desensitization and sequestration by the opioid agonists, etorphine and morphine. We find that, whereras both morphine and etorphine effectively activate the μOR, unlike etorphine, morphine does not induce GRK-mediated receptor phosphorylation. The inability of morphine to induce GRK-mediated μOR phosphorylation is associated with impaired β-arrestin binding resulting in a lack of μOR endocytosis. Interestingly, GRK overexpression overcomes the inability of morphine to promote β-arrestin binding and μOR sequestration. Following the overexpression of GRK2, μOR responses to both etorphine and morphine are indistinguishable. These observations may have important implications for our understanding of both basic GPCR pharmacology and pathophysiological changes associated with drug tolerance and addiction.

Recently, several components required for the sequestration of many GPCRs were identified. It was found that the same proteins mediating GPCR desensitization, GRKs and arrestins, contribute directly to the clathrin-mediated endocytosis of the β2AR, CCR-5, D2 dopamine receptor, and m2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (24, 25, 27–32, 38). We find here that the preferred mechanism of μOR endocytosis in HEK 293 cells is via the same β-arrestin- and dynamin-dependent clathrin-coated vesicle-mediated pathway first described for the β2AR (24, 31, 39). However, unlike the β2AR, sequestration of the μOR is exquisitely dependent on GRK-mediated phosphorylation. This is highlighted by the observations that etorphine-mediated μOR endocytosis could be effectively blocked by using a dominant-negative GRK mutant construct and that morphine promoted the internalization of the μOR only following the overexpression of GRK2, but not β-arrestin. This differs significantly from β2AR mutants lacking putative GRK phosphorylation sites whose sequestration can be facilitated by the overexpression of β-arrestin alone, and CCR-5, which requires overexpression of both GRK and β-arrestin proteins to allow sequestration in HEK 293 cells (24, 27). These observations suggest a more critical role for GRK-mediated phosphorylation in initiating GPCR sequestration than originally envisaged. Moreover, they indicate receptor-type differences in affinity for GRK and arrestin proteins. It is likely that the observed ability of the β2AR to sequester in the absence of GRK phosphorylation is the exception rather than the rule and that for many GPCRs, β-arrestin binding may be more exquisitely GRK regulated.

The observation that, although both etorphine and morphine are agonists, only etorphine induces GRK-mediated μOR phosphorylation in HEK 293 cells, indicates that different agonist-activated conformations of the μOR may exist. Therefore, the etorphine-activated receptor may have a greater affinity for GRKs than the morphine-activated receptor. As a consequence, a two-state model (A+R → AR*) of receptor activation may not adequately reflect the multiple agonist-specific conformations required for GPCR interaction with regulatory proteins. We have previously demonstrated that mutations made to the NPXXY motif in the seventh transmembrane domain of the β2AR differentially affect its G protein coupling and GRK-mediated phosphorylation, and that GRK overexpression can influence phosphorylation and sequestration of these receptors (25, 40). More recently, β-arrestin binding has been reported to stabilize the high-affinity conformation state of both the β2AR and m2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (41). This study on the μOR provides evidence that the stability of the receptor activation state required for GRK phosphorylation and β-arrestin binding can be differentially modulated by the binding of distinct agonists. This agonist binding to GPCRs probably involves ionic and hydrogen bonding interactions with residues in different transmembrane domains of the receptors (42, 43). Therefore, the molecular basis of the observed differential regulation of μOR responsiveness by different opioid agonists may likely be explained by differences in their chemical structures and relative abilities to interact with amino acid residues in the transmembrane domains of the μOR. Additionally, the existence of opioid agonists that discriminate between receptor/G protein coupling and receptor desensitization suggests that the development of ligands that lead to the activation but not the desensitization of GPCRs should be possible.

Although second messenger-dependent protein kinases, in particular protein kinase C, may contribute to the agonist-induced phosphorylation of the μOR (44, 45), there is a strong correlation between GRK-mediated μOR phosphorylation, β-arrestin binding, and μOR desensitization (refs. 11 and 12; see Figs. 2 and 3). In this study, GRK2 overexpression attenuated μOR-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity in response to both etorphine and morphine, indicating that GRK-mediated phosphorylation is important for μOR desensitization in response to different opioid agonists in HEK 293 cells. This is supported by studies in Xenopus oocytes, where coexpression of GRK3 and β-arrestin2 synergistically attenuated μOR-activated potassium conductance (11) and by studies demonstrating parallels between μOR phosphorylation and desensitization in response to distinct opioid ligands (12). However, the observation that GRK2 overexpression was required to promote μOR phosphorylation and β-arrestin recruitment suggests that differences in cell- and tissue-specific GRK expression levels are important. GRK protein expression levels will not only regulate the extent of μOR endocytosis in response to different opioid ligands but will also influence the level of μOR desensitization.

Opioid tolerance is a complex phenomenon that involves changes at the level of opioid receptors as well as the activation of compensatory systems. For instance, there is mounting evidence for a potential role of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors in mediating morphine tolerance. However, the ability of GRK overexpression to facilitate morphine-induced μOR phosphorylation and β-arrestin binding is particularly intriguing considering recent hypotheses surrounding the contribution of μOR desensitization and intracellular trafficking to the development of drug tolerance and dependence associated with opioid addiction (5–9). The differential regulation of μOR sequestration by distinct agonists suggests that the higher liability for morphine to develop tolerance and addiction might be attributable to its inability to promote μOR sequestration, a critical step in GPCR resensitization (22, 26). However, the present results suggest that GRK-mediated mechanisms of μOR desensitization in response to morphine stimulation may also be impaired in vivo. Interestingly, following chronic morphine treatment of rats, GRK2 and β-arrestin protein levels are specifically upregulated in the locus coeruleus (33). The assumption at the time, based on available experimental data, was that the increased GRK and β-arrestin expression contributed to increased receptor desensitization and the observed development of opioid tolerance. However, because GRKs and β-arrestins regulate both GPCR desensitization and resensitization, the consequence of increased GRK and β-arrestin expression levels could be influenced by this duality. Indeed, impaired morphine-induced μOR sequestration can be overcome by supplementing GRK protein. This suggests that the observed adaptation in the levels of GRK and β-arrestin proteins following chronic morphine treatment might antagonize rather than confer the development of drug tolerance. The relative contribution of increased GRK expression to drug tolerance and dependence should be testable in transgenic mice targeted to specifically overexpress GRK2 in the locus coeruleus and/or other brain regions associated with drug tolerance.

In summary, this study uncovers a fundamental molecular mechanism underlying the regulation of μOR cellular signaling and highlights further a universal and pleiotropic role of GRK-mediated phosphorylation and β-arrestin in multiple GPCR regulatory processes, including receptor desensitization and sequestration. Moreover, it highlights the need for the development of new experimental paradigms to test the relative contributions of opioid receptor desensitization and resensitization to both the development and amelioration of drug dependence and tolerance. The development of animal models genetically engineered to either overexpress or disrupt the expression of GRK and/or β-arrestin should greatly facilitate this goal (46, 47).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Linda Cyzyk for expert technical assistance and Dr. William Wetsel for his helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant NS 19576, an unrestricted Neuroscience Award from Bristol–Myers Squibb, an unrestricted grant from Zeneca Pharmaceutical (to M.G.C.), and National Institutes of Health Grant HL 03422 (to L.S.B.). S.A.L. is a recipient of a fellowship award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

ABBREVIATIONS

- μOR

μ-opioid receptor

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- GRK

G protein-coupled receptor kinase

- β2AR

β2-adrenergic receptor

- βarr2/GFP

β-arrestin2 green fluorescent protein conjugate

- HA

hemagglutinin

- A

agonist

- R

receptor

- R*

activated receptor

References

- 1.Cherny N I. Drugs. 1996;51:713–737. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199651050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kieffer B L. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1995;15:615–635. doi: 10.1007/BF02071128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piros E T, Hales T G, Evans C J. Neurochem Res. 1996;21:1277–1285. doi: 10.1007/BF02532368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Standifer K M, Pasternak G W. Cell Signalling. 1997;9:237–248. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(96)00174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raynor K, Kong H, Law S, Heerding J, Tallent M, Livingston F, Hines J, Reisine T. NIDA Res Monogr. 1996;161:83–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mestek A, Chen Y, Yu L. NIDA Res Monogr. 1996;161:104–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nestler E J, Aghajanian G K. Science. 1997;278:58–63. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keith D E, Murray S R, Zaki P A, Chu P C, Lissin D V, Kang L, Evans C J, von Zastrow M. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19021–19024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sternini C, Spann M, Anton B, Keith D E, Jr, Bunnett N W, von Zastrow M, Evans C, Brecha N C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9241–9246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blake A D, Bot G, Freeman J C, Reisine T. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:782–790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovoor A, Nappey V, Kieffer B L, Chavkin C. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27605–27611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu Y, Zhang L, Yin X, Sun H, Uhl G R, Wang J B. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28869–28874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, Yu Y, Mackin S, Weight F F, Uhl G R, Wang J B. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11449–11454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pak Y, O’Dowd B F, George S R. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24961–24965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arden J R, Segredo V, Wang Z, Lameh J, Sadée W. J Neurochem. 1995;65:1636–1645. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65041636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chakrabarti S, Yang W, Law P Y, Loh H H. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:105–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu P, Murray S, Lissin D, von Zastrow M. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27124–27130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaudriault G, Nouel D, Dal Farra C, Beaudet A, Vincent J-P. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2880–2888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capeyrou R, Riond J, Corbani M, Lepage J-F, Bertin B, Emorine L J. FEBS Lett. 1997;415:200–205. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segredo V, Burford N T, Lameh J, Sadée W. J Neurochem. 1997;68:2395–2404. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68062395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cvejic S, Devi L A. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26959–26964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.26959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferguson S S G, Barak L S, Zhang J, Caron M G. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996;74:1095–1110. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-74-10-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lefkowitz R J. Cell. 1993;74:409–412. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80042-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferguson S S G, Downey W E, III, Colapietro A-M, Barak L S, Ménard L, Caron M G. Science. 1996;271:363–366. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferguson S S G, Ménard L, Barak L S, Koch W J, Colapietro A-M, Caron M G. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24782–24789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Barak L S, Winkler K E, Caron M G, Ferguson S S G. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27005–27014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aramori I, Ferguson S S G, Bieniasz P D, Zhang J, Cullen B R, Caron M G. EMBO J. 1997;16:4606–4616. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuga H, Kameyama K, Haga T, Kurose H, Nagao T. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32522–32527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlador M L, Nathanson N M. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18882–18890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iacovelli L, Franchetti R, Masini M, De Blasi A. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1138–1146. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.9.8885248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J, Ferguson S S G, Barak L S, Ménard L, Caron M G. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18302–18305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goodman O B, Jr, Krupnick J G, Santini F, Gurevich V V, Penn R B, Gagnon A W, Keen J H, Benovic J L. Nature (London) 1996;383:447–450. doi: 10.1038/383447a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terwilliger R Z, Ortiz J, Guitart X, Nestler E J. J Neurochem. 1994;63:1983–1986. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63051983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arvidsson U, Riedl M, Chakrabarti S, Lee J H, Nakano A H, Dado R J, Loh H H, Law P Y, Wessendorf M W, Elde R. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3328–3341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03328.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barak L S, Ferguson S S G, Zhang J, Caron M G. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27497–27500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cullen B R. Methods Enzymol. 1987;152:684–704. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salomon Y. Methods Enzymol. 1991;195:22–28. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)95151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Itokawa M, Toru M, Ito K, Tsuga H, Kameyama K, Haga T, Arinami T, Hamaguchi H. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:560–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.von Zastrow M, Kobilka B K. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3530–3538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barak L S, Ménard L, Ferguson S S G, Colapietro A-M, Caron M G. Biochemistry. 1995;34:15407–15414. doi: 10.1021/bi00047a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gurevich V V, Pals-Rylaarsdam R, Benovic J L, Hosey M M, Onorato J J. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28849–28852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tota M R, Candelore M R, Dixon R A, Strader C D. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991;12:4–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90479-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferguson S S G, Caron M G. In: Molecular Mechanisms of Neuronal Communication. Fuxe K, Hokfelt T, Olson L, Ottoson D, editors. Oxford, U.K.: Elsevier; 1996. pp. 219–242. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mestek A, Hurley J H, Bye L S, Campbell A D, Chen Y, Tian M, Liu J, Schulman H, Yu L. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2396–2406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-02396.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Y, Yu L. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7839–7842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jaber M, Koch W J, Rockman H, Smith B, Bond R A, Sulik K K, Ross J, Jr, Lefkowitz R J, Caron M G, Giros B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12974–12979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peppel K, Boekhoff I, McDonald P, Breer H, Caron M G, Lefkowitz R J. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25425–25428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]