Abstract

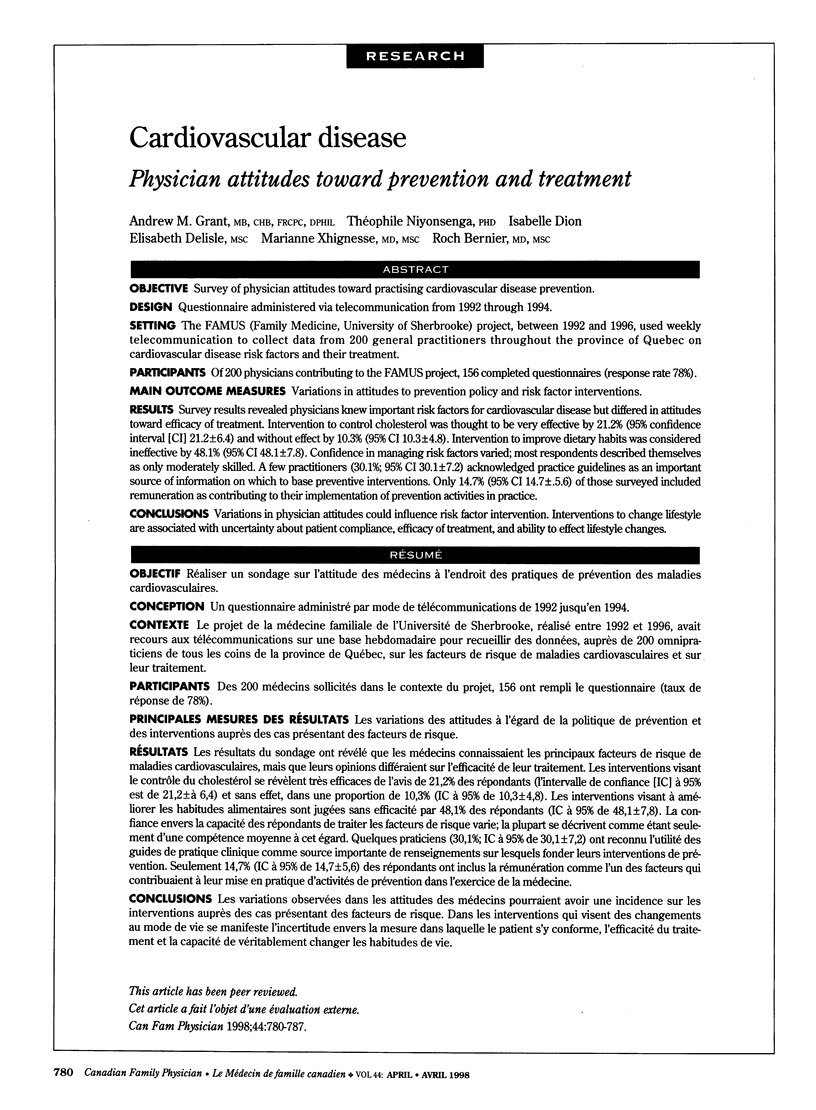

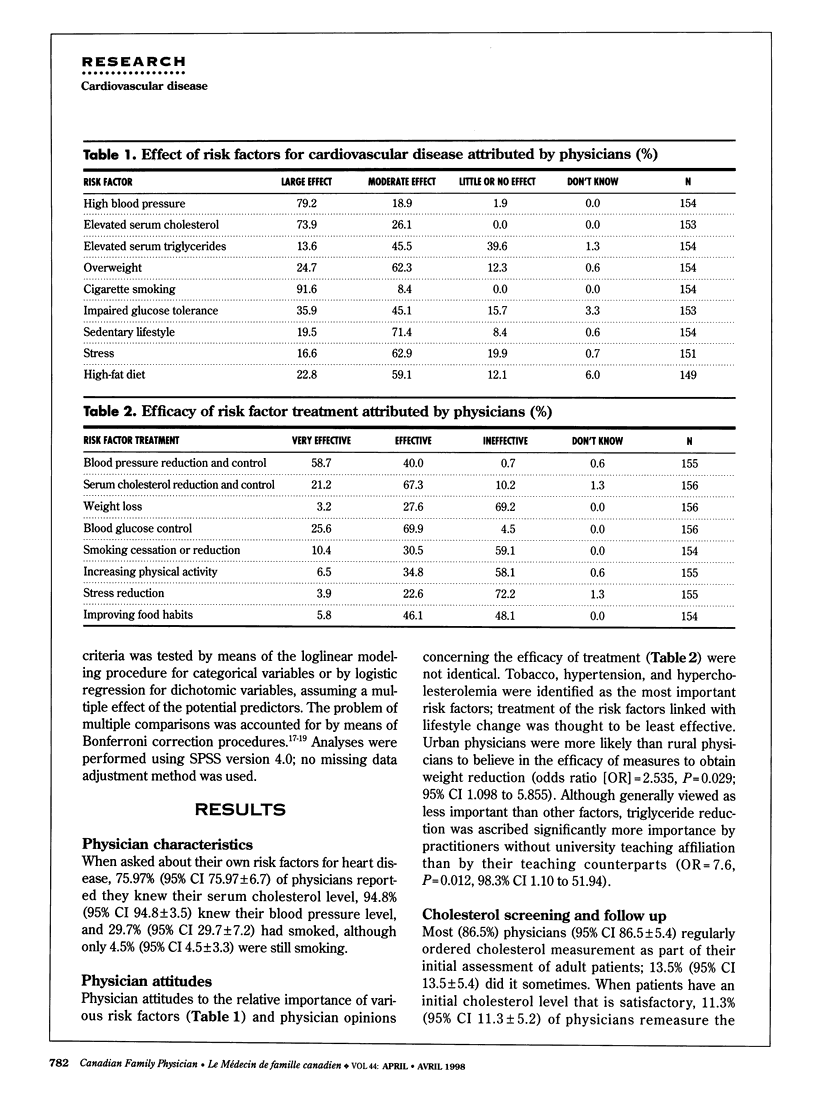

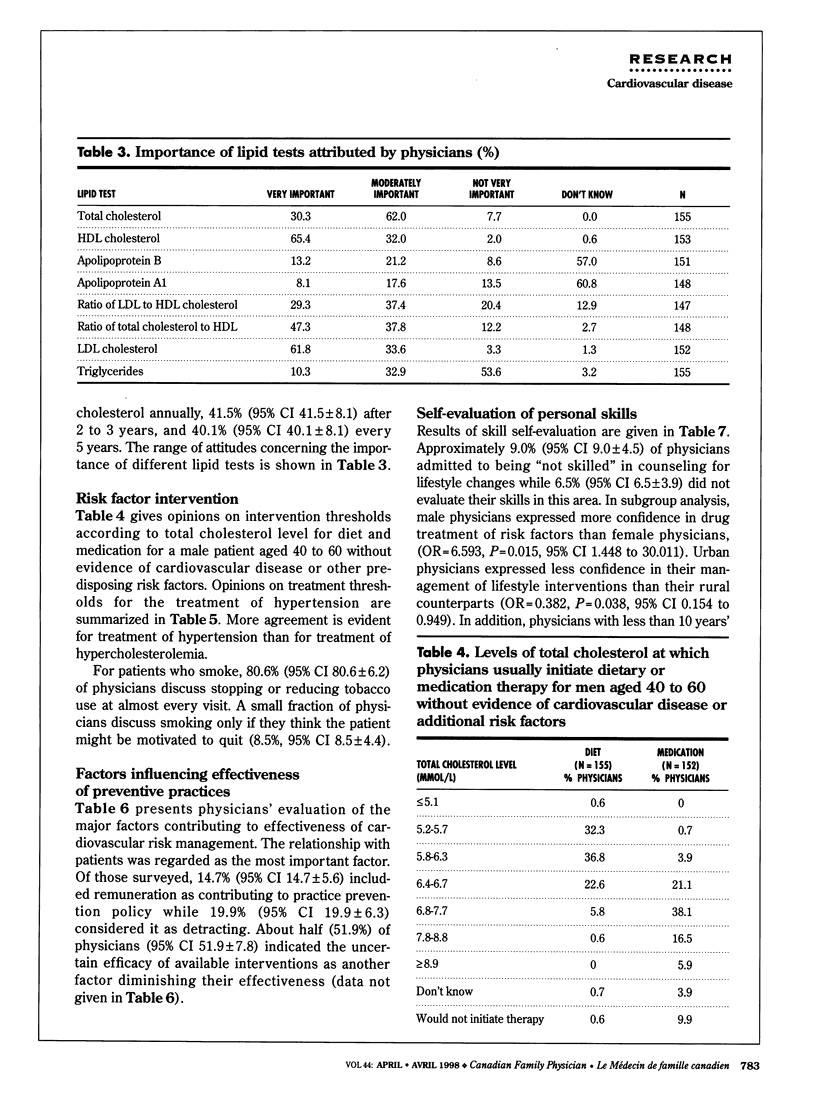

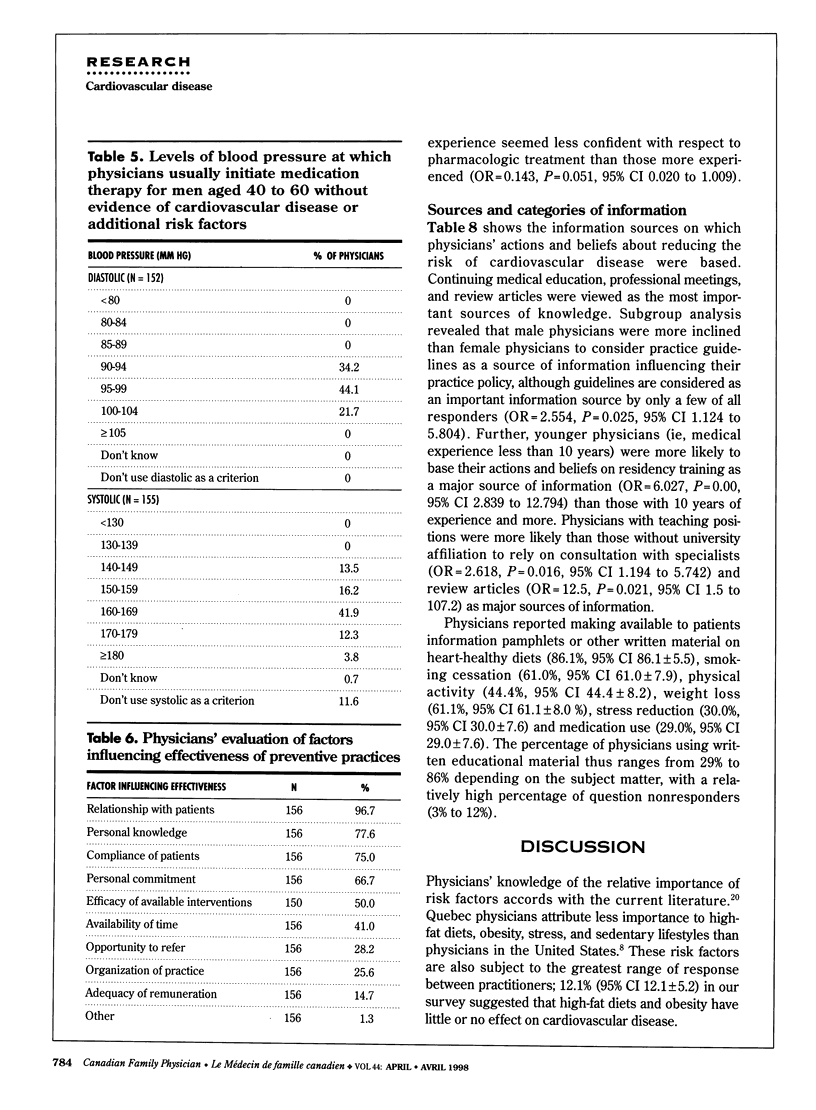

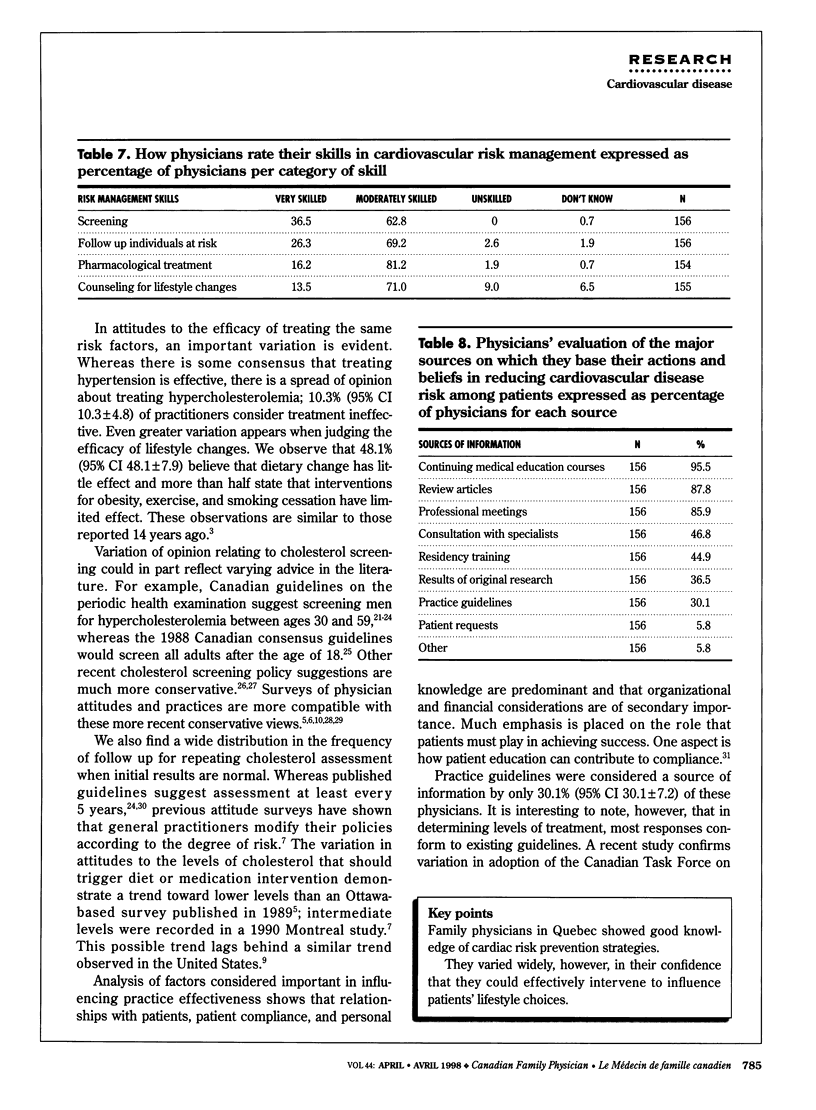

OBJECTIVE: Survey of physician attitudes toward practising cardiovascular disease prevention. DESIGN: Questionnaire administered via telecommunication from 1992 through 1994. SETTING: The FAMUS (Family Medicine, University of Sherbrooke) project, between 1992 and 1996, used weekly telecommunication to collect data from 200 general practitioners throughout the province of Quebec on cardiovascular disease risk factors and their treatment. PARTICIPANTS: Of 200 physicians contributing to the FAMUS project, 156 completed questionnaires (response rate 78%). MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: Variations in attitudes to prevention policy and risk factor interventions. RESULTS: Survey results revealed physicians knew important risk factors for cardiovascular disease but differed in attitudes toward efficacy of treatment. Intervention to control cholesterol was thought to be very effective by 21.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] 21.2 +/- 6.4) and without effect by 10.3% (95% CI 10.3 +/- 4.8). Intervention to improve dietary habits was considered ineffective by 48.1% (95% CI 48.1 +/- 7.8). Confidence in managing risk factors varied; most respondents described themselves as only moderately skilled. A few practitioners (30.1%; 95% CI 30.1 +/- 7.2) acknowledged practice guidelines as an important source of information on which to base preventive interventions. Only 14.7% (95% CI 14.7 +/- 5.6) of those surveyed included remuneration as contributing to their implementation of prevention activities in practice. CONCLUSIONS: Variations in physician attitudes could influence risk factor intervention. Interventions to change lifestyle are associated with uncertainty about patient compliance, efficacy of treatment, and ability to effect lifestyle changes.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bostick R. M., Luepker R. V., Kofron P. M., Pirie P. L. Changes in physician practice for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 1991 Mar;151(3):478–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinwoodie A., Frohlich J., Hoag G., Luxton A. W., McQueen M., Rasaiah B., Salkie M. L. Position statement of the CSCC and CAP Task Force on the measurement of lipids for the assessment of risk of CHD. Clin Biochem. 1989 Jun;22(3):231–237. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(89)80082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar J. W., Fortmann S. P., Flora J. A., Taylor C. B., Haskell W. L., Williams P. T., Maccoby N., Wood P. D. Effects of communitywide education on cardiovascular disease risk factors. The Stanford Five-City Project. JAMA. 1990 Jul 18;264(3):359–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant A., Delisle E., Dubois S., Niyonsenga T., Bernier R. Implementation of a province-wide computerized network in Quebec: the FAMUS Project. MD Comput. 1995 Jan-Feb;12(1):45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant A., Lussier Y., Delisle E., Dubois S., Bernier R. The TEAM evaluation approach to Project FAMUS, a pan-Canadian risk register for primary care. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1992:734–738. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S. A., Lowensteyn I., Esrey K. L., Steinert Y., Joseph L., Abrahamowicz M. Do doctors accurately assess coronary risk in their patients? Preliminary results of the coronary health assessment study. BMJ. 1995 Apr 15;310(6985):975–978. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6985.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt G. H., Bombardier C., Tugwell P. X. Measuring disease-specific quality of life in clinical trials. CMAJ. 1986 Apr 15;134(8):889–895. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg Y., Benjamini Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat Med. 1990 Jul;9(7):811–818. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langner N. R., Hasselback P. D., Dunkley G. C., Corber S. J. Attitudes and practices of primary care physicians in the management of elevated serum cholesterol levels. CMAJ. 1989 Jul 1;141(1):33–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurier D., Maheux B. Hypercholestérolémie: attitudes et pratiques des omnipraticiens lavallois. Union Med Can. 1993 May-Jun;122(3):176–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton A. L. Cholesterol: consensus and controversy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(10):1021–1022. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90146-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas J., Anderson G. M., Domnick-Pierre K., Vayda E., Enkin M. W., Hannah W. J. Do practice guidelines guide practice? The effect of a consensus statement on the practice of physicians. N Engl J Med. 1989 Nov 9;321(19):1306–1311. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911093211906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann K. V., Putnam R. W. Barriers to prevention: physician perceptions of ideal versus actual practices in reducing cardiovascular risk. Can Fam Physician. 1990 Apr;36:665–670. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann K. V., Putnam R. W. Physicians' perceptions of their role in cardiovascular risk reduction. Prev Med. 1989 Jan;18(1):45–58. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(89)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen T. A., Strandberg T. E. Implications of recent results of long term multifactorial primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Ann Med. 1992 Apr;24(2):85–89. doi: 10.3109/07853899209148332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan P. P., Lindsay E. A. Screening in the office for elevated cholesterol levels: still a dilemma. CMAJ. 1994 Jul 1;151(1):25–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe C. E., Hahn D. F., Betts N. M. Physicians' perspectives on cholesterol and heart disease. J Am Diet Assoc. 1991 Feb;91(2):189–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen M. A., Logsdon D. N., Demak M. M. Prevention and health promotion in primary care: baseline results on physicians from the INSURE Project on Lifecycle Preventive Health Services. Prev Med. 1984 Sep;13(5):535–548. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(84)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. E., Herbert C. P. Preventive practice among primary care physicians in British Columbia: relation to recommendations of the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. CMAJ. 1993 Dec 15;149(12):1795–1800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sox H. C., Jr Screening for lipid disorders under health system reform. N Engl J Med. 1993 Apr 29;328(17):1269–1271. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford R. S., Blumenthal D., Pasternak R. C. Variations in cholesterol management practices of U.S. physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997 Jan;29(1):139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum T. N., Sampalis J. S., Battista R. N., Rosenberg E. R., Joseph L. Early detection and treatment of hyperlipidemia: physician practices in Canada. CMAJ. 1990 Nov 1;143(9):875–881. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Weijden T., Dansen A., Schouten B. J., Knottnerus J. A., Grol R. P. Comparison of appropriateness of cholesterol testing in general practice with the recommendations of national guidelines: an audit of patient records in 20 general practices. Qual Health Care. 1996 Dec;5(4):218–222. doi: 10.1136/qshc.5.4.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]