Abstract

Intracellular Mg2+ (Mgi2+) blocks single-channel currents and modulates the gating kinetics of NMDA receptors. However, previous data suggested that Mgi2+ inhibits whole-cell current less effectively than predicted from excised-patch measurements. We examined the basis of this discrepancy by testing three hypothetical explanations.

To test the first hypothesis, that control of free Mgi2+ concentration ([Mg2+]i) during whole-cell recording was inadequate, we measured [Mg2+]i using mag-indo-1 microfluorometry. The [Mg2+]i measured in cultured neurons during whole-cell recording was similar to the pipette [Mg2+] measured in vitro, suggesting that [Mg2+]i was adequately controlled.

To test the second hypothesis, that open-channel block by Mgi2+ was modified by patch excision, we characterised the effects of Mgi2+ using cell-attached recordings. We found the affinity and voltage dependence of open-channel block by Mgi2+ similar in cell-attached and outside-out patches. Thus, the difference between Mgi2+ inhibition of whole-cell and of patch currents cannot be attributed to a difference in Mgi2+ block of single-channel current.

The third hypothesis tested was that the effect of Mgi2+ on channel gating was modified by patch excision. Results of cell-attached recording and modelling of whole-cell data suggest that the Mgi2+-induced stabilisation of the channel open state is four times weaker after patch excision than in intact cells. This differential effect of Mgi2+ on channel gating explains why Mgi2+ inhibits whole-cell NMDA responses less effectively than patch responses.

The free concentration of Mgi2+, the second most abundant intracellular cation, is regulated at approximately 5–10 % of the total concentration of Mgi2+ through buffering, ion exchange and pumping (for reviews see Flatman, 1991; Romani & Scarpa, 1992). Mgi2+ modulates diverse types of ionic channels, including NMDA receptors, a glutamate receptor subtype important in many aspects of brain physiology and pathology (e.g. Morris et al. 1991; Sakimura et al. 1995; Choi, 1995; Rothman & Olney, 1995). In experiments on membrane patches from cultured neurons, Mgi2+ was found to block ionic conduction through the channel of the NMDA receptors (Johnson & Ascher, 1990; Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996a). While Mgi2+ blocks, it weakly stabilises the open state of the channel of native NMDA receptors in membrane patches (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b) and of some mutant receptors (Kupper et al. 1998), though not of wild-type receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Wollmuth et al. 1998; Kupper et al. 1998). Stabilisation of the channel open state weakens the ability of a channel blocker to inhibit steady-state currents (Neher, 1983). Correspondingly, Mgi2+ inhibits steady-state NMDA responses of outside-out patches somewhat less effectively than it inhibits single-channel currents (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b).

Intriguingly, Mgi2+ appeared to inhibit NMDA responses measured in whole-cell experiments much less effectively than steady-state responses measured in patch experiments (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b). Potential explanations for this observation based on inadequate voltage control or a non-uniform [Mg2+]i in neurons were eliminated by experiments on Chinese hamster ovary cells transfected with NMDA receptors (Li-Smerin et al. 2000). At least three other hypotheses can be considered to explain the discrepancy between inhibition by Mgi2+ in whole-cell and patch experiments: (1) [Mg2+]i during whole-cell recordings is maintained by cellular machinery below the [Mg2+] in the pipette solution; (2) patch excision enhances channel block by Mgi2+ implying that channel block is weak in intact neurons; and (3) patch excision attenuates stabilisation of the open state by Mgi2+ implying that Mgi2+ strongly stabilises the open state in intact neurons.

Here we have tested these three hypotheses. We found that neither poor control of [Mg2+]i during whole-cell recording nor a change in channel block by Mgi2+ following patch excision could explain the preparation dependence of Mgi2+ inhibition. However, we found that patch excision weakens the ability of Mgi2+ to stabilise the channel open state, and that this effect can fully explain the difference between inhibition by Mgi2+ of whole-cell and patch currents. In addition to their implications for NMDA receptor regulation, our results permit estimation of the free [Mg2+]i of any cell that expresses NMDA receptors using cell-attached recordings.

METHODS

Cell culture

Primary neuronal cultures were prepared following the procedures described in Li-Smerin & Johnson (1996a). All procedures using animals were in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the University of Pittsburgh's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Briefly, 16-day-old pregnant rats (Sprague-Dawley) were killed by CO2 inhalation; the embryos (8–10) were rapidly removed and kept cold (5 °C) during removal of the brain. A suspension of dissociated cells was prepared from the hemispheres and plated onto glass coverslips in 35 mm Petri dishes on which either poly-l-lysine had been previously coated or a monolayer of glia had been previously grown. The glass coverslips were 15 mm in diameter for the electrophysiological studies and 31 mm in diameter for the microfluorometry studies. Neurons were used after 7–40 days in culture.

Microfluorometry

Recording conditions

Experiments were performed on an inverted microscope (Olympus IMT2) equipped with a × 40 oil-immersion objective (1.3 NA). The fluorescent dye mag-indo-1 was excited with a 100 W mercury lamp at a wavelength of 340 nm and the fluorescence emissions at 405 and 495 nm were measured with two photomultiplier tubes. The ratio of fluorescence emission at these two wavelengths (R, or F405/F495) was recorded after background fluorescence, measured at each wavelength, was subtracted. Data were filtered at 10 Hz.

Solutions

Six solutions were used to calibrate mag-indo-1 (calibration solutions, Table 1). The four pipette solutions that were used in Li-Smerin & Johnson (1996a,b) to study the effects of Mgi2+ on NMDA receptors were used to measure [Mg2+]i during whole-cell recording (whole-cell recording solutions, Table 1). The osmolality of each of the calibration and whole-cell recording solutions was 260–270 mosmol kg−1. The control extracellular solution contained (mm): 140 NaCl, 2.8 KCl, 1 CaCl2 and 10 Hepes. To elevate [Mg2+]i in neurons, Mg2++ NMDA + glycine solution was used, which contained: 91 mm MgCl2, 2 mm EGTA, 10 mm Hepes, 100 μm NMDA and 10 μm glycine.

Table 1.

Composition of solutions used for mag-indo-1 calibration and measurement of [Mg2+]i during whole-cell recording

| Solution name | [CsCl](mm) | [Hepes] (mm) | [EGTA] (mm) | [EDTA] (mm) | [4-fluoro-APTRA] (mm) | [MgCl2](mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calibration | ||||||

| 0 Mg2+ | 125 | 10 | 10 | 2 | — | — |

| 3.4 mM Mg2+ | 103 | 10 | — | — | 10 | 8.4 |

| 3.4 mM Mg2+, high APTRA | 26 | 10 | — | — | 30 | 18.4 |

| 6.8 mM Mg2+ | 88 | 10 | — | — | 10 | 13.5 |

| 20 mM Mg2+ | 68 | 10 | — | — | 10 | 28.6 |

| 50 mM Mg2+ | 25 | 10 | — | — | 10 | 59.4 |

| 89 mM Mg2+ | — | 10 | 2 | — | — | 91 |

| Whole-cell recording | ||||||

| 0 Mg2+ | 125 | 10 | 10 | — | — | — |

| Low Mg2+ | 125 | 10 | 10 | — | — | 1.9 |

| Intermediate Mg2+ | 125 | 10 | 10 | — | — | 5.3 |

| High Mg2+ | 125 | 10 | 10 | — | — | 15 |

In vitro measurement of [Mg2+]

In vitro measurements of mag-indo-1 fluorescence were made following addition of 50 μm mag-indo-1 to each solution. The background-subtracted value of the fluorescence ratio R was recorded with about 50 μl of solution placed on the glass coverslip that formed the bottom of the recording chamber. The value of R was converted to free [Mg2+] using an in vitro calibration curve measured using each of the calibration solutions (Table 1) except the 3.4 mm Mg2+, high APTRA solution. The Mg2+ buffer 2-amino-4-fluorophenol-N,N,O-triacetic acid (4-fluoro-APTRA; Levy et al. 1988) was used to ensure a stable [Mg2+] in the calibration solutions during both in vitro and in situ (next section) measurements. Free [Mg2+] was calculated based on the measured KD of 4-fluoro-APTRA for Mg2+ at 22 oC of 3.4 mm (Haugland, 1992). We performed two sets of experiments to test the accuracy of the calculated free [Mg2+]. First, to ensure that the [MgCl2] added to each solution was accurate, we compared the R values of solutions made from two different 1 m MgCl2 solutions at five different [Mg2+] values. One solution was made from solid MgCl2.6H2O (Sigma), and the other was a 1 m standard MgCl2 solution (Sigma). There were no significant or systematic differences in the R values of the two sets of solutions. Second, we compared the R values of the 4-fluoro-APTRA-containing calibration solutions with the R values of solutions containing only MgCl2 at the free concentrations calculated for the corresponding calibration solutions (0, 3.4, 6.8, 20 and 50 mm). Again, no significant or systematic differences in the R values were observed, verifying the accuracy of the reported KD of 4-fluoro-APTRA.

The R values of the calibration solutions were fitted with the equation (Grynkiewicz et al. 1985):

| (1) |

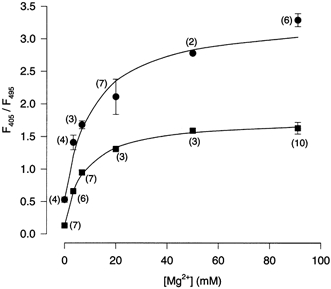

where Rmin is the value of R in 0 Mg2+ and Rmax is the value of R in a saturating [Mg2+]. Equation (1) was fitted to mag-indo-1 calibration curves with Rmin fixed at the value of R measured with the 0 Mg2+ calibration solution and Rmax and Kapp allowed to vary as free parameters. The results of curve fitting (Fig. 2) yielded the following equation, which was used to calculate the free [Mg2+] of the whole-cell recording solutions: [Mg2+]=7.3 mm(R − 0.13)/(1.76 − R).

Figure 2. Calibration of mag-indo-1.

The values of R (F405/F495) for each of the calibration solutions (Table 1) measured in vitro (▪) and in situ (•) are plotted. In vitro measurements were made with the calibration solution placed in the recording chamber. In situ measurements are the values of R averaged for each neuron from 10–20 min (see Fig. 1) after initiation of whole-cell recording with the calibration solution in the recording pipette. The data points were fitted (lines) with eqn (1) as described in Methods. Each point represents mean ±s.e.m.; numbers of experiments are shown in parentheses.

In situ measurement of [Mg2+]i

The free [Mg2+] inside neurons during whole-cell recording was measured using mag-indo-1. Cells were bathed in the control extracellular solution. During some in situ experiments, 0.2 μm TTX was added to the control extracellular solution to inhibit voltage-gated Na+ channels; the presence of TTX had no apparent effect on [Mg2+]i. Whole-cell pipettes pulled from borosilicate thin-walled glass with filaments (Clark Electromedical, Reading, UK) were filled with a calibration or whole-cell recording solution (Table 1) containing 50 μm mag-indo-1. The whole-cell configuration was established and monitored using a List EPC-9 amplifier and Pulse software (HEKA Electronics GmbH, Germany). Background fluorescences at 409 and 495 nm were measured with each pipette while in the cell-attached configuration and subtracted from values measured later during whole-cell recording before R was calculated.

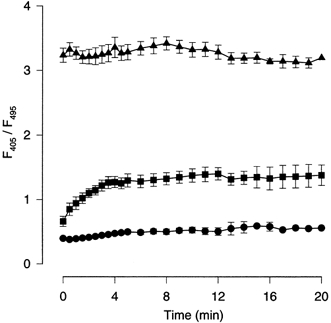

Figure 1 shows that with an intermediate [Mg2+] in the recording pipette (the 3.4 mm Mg2+ solution), R reached a steady-state value within several minutes of formation of the whole-cell configuration. This observation is consistent with previous reports of the time course of solution exchange during whole-cell dialysis (e.g. Pusch & Neher, 1988; Zarei & Dani, 1995). To calculate a steady-state value of R, the data points from 10–20 min after initiation of whole-cell recordings were averaged for each cell. R reached its steady-state value by the time of the first measurement of R, when either the 89 mm or the 0 Mg2+ solutions were in the recording pipette (Fig. 1). The rapid change of R observed with the 89 mm solution probably resulted from the high [Mg2+] overwhelming the endogenous Mg2+ buffering capacity of the cell. In addition, 89 mm Mg2+ is a more than saturating [Mg2+] for mag-indo-1 (Fig. 2), and so a plateau in the R value would be reached before exchange is complete. With the 0 Mg2+ solution, the rapid change of R probably resulted from the presence of 2 mm EDTA in the solution. This concentration of EDTA is much higher than the resting neuronal [Mg2+]i, and thus diffusion of EDTA into the cell would be expected to lower the free [Mg2+] rapidly.

Figure 1. Time dependence of fluorescence ratio during whole-cell dialysis.

The whole-cell recording pipette contained 50 μm mag-indo-1 in the 0 Mg2+ (•), 3.4 mm Mg2+ (▪) or 89 mm Mg2+ (▴) calibration solutions (see Table 1). The value of R (F405/F495) was obtained as soon as the whole-cell configuration was formed (0 min) and then measured as a function of dialysis time: every 30 s for the first 5 min and every 1 min for the remaining 15 min. Neurons were held at a membrane potential of −60 mV. Symbols represent the mean ±s.e.m. from 2–10 cells for the points with error bars and one cell for the points without error bars. The data points are connected by straight lines.

An in situ mag-indo-1 calibration curve was made using the same calibration solutions (Table 1) used for in vitro measurements. To determine whether 10 mm 4-fluoro-APTRA was sufficient to buffer [Mg2+]i in situ, we measured R in situ using a second pipette solution with a calculated free [Mg2+] of 3.4 mm, but with a higher concentration (30 mm) of 4-fluoro-APTRA, the 3.4 mm Mg2+, high-APTRA solution (Table 1). The values of R obtained with this solution in situ, 1.41 ± 0.05 (n = 2), were not different from the values of 1.41 ± 0.11 (n = 4) obtained with the 3.4 mm Mg2+ calibration solution that contained 10 mm 4-fluoro-APTRA. The similarity of these R values suggests that 10 mm 4-fluoro-APTRA was sufficient for buffering [Mg2+]iin situ.

The in situ calibration curve was fitted with eqn (1) as described above. The results (Fig. 2) yielded the following equation, which was used to calculate the free [Mg2+] of the whole-cell recording solutions during whole-cell recording: [Mg2+]=10.6 mm (R − 0.53)/(3.32 − R).

[Mg2+]i measurement in intact neurons

Intact neurons (neurons in primary culture whose membranes had not been ruptured with a patch pipette) were loaded with mag-indo-1 by incubation at 37 °C for 5 min in 5 μm mag-indo-1 AM (acetoxy-methyl ester form of mag-ingo-1), 0.5 % DMSO and 0.5 % BSA dissolved in the control extracellular solution. Following this incubation, neurons were reincubated at 37 °C for another 60 min without the dye, but with 0.5 % BSA. To ensure that the 60 min reincubation time was sufficient for a complete hydrolysis by endogenous esterase of the AM form of the dye, we measured the value of R as a function of the duration of reincubation. The value of R was 0.26 ± 0.03 for 30 min (n = 7), 0.31 ± 0.01 for 60 min (n = 110), 0.29 ± 0.05 for 90 min (n = 11) and 0.31 ± 0.04 for 120 min (n = 9) reincubation period. The differences in these values of R were not significant. The background fluorescence signal, mainly due to the presence of the dye in glia underneath neurons, was measured in regions adjacent to the neurons selected for [Mg2+]i measurements. This background signal (typically 10–20 % of the absolute fluorescence emission measured in neurons) was subtracted before measuring the values of R in neurons. The value of R measured in intact neurons was converted to [Mg2+]i based on the in situ calibration curve (Fig. 2).

Electrophysiology

Cell-attached and inside-out patch recordings

Recordings were performed with a pipette solution that contained 140 mm CsCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 2.8 mm KCl, 10 mm Hepes, 2 μm strychnine to inhibit glycine-activated channels and 0.2 μm TTX. The presence of 2 μm strychnine did not influence the amplitude of single-channel NMDA receptor currents (Bertolino & Vicini, 1988), as the i–V relation at negative potentials was linear (Fig. 6). Two bath solutions were used during patch recording. The normal (1 mm) Ca2+ extracellular solution was made by adding 5 mm 4-AP and 0.2 μm TTX to the control extracellular solution described above. The low-Ca2+ extracellular solution was made by replacing the 1 mm CaCl2 in the normal Ca2+ extracellular solution with 5 mm EDTA and 2.5 mm CaCl2 to reduce free [Ca2+] to 70 nm. During cell-attached patch recordings, neurons were perfused with bath solutions with a five-barrel fast perfusion system (Blanpied et al. 1997). Recording pipettes (resistance, 2–4 MΩ) were coated with Sylgard (Dow Corning Corp.) and lightly fire polished. Single-channel currents were recorded using an Axopatch-1D amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). Patch current was low-pass filtered (4-pole Bessel) at 10 kHz (-3 dB frequency), sampled at 44 kHz with a Neuro-Corder (Model DR-890; Neuro Data Instruments Corp., New York, USA) and stored on magnetic tapes for off-line analysis.

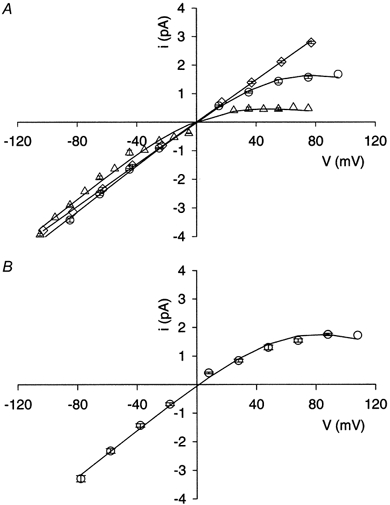

Figure 6. Voltage-dependent block by Mgi2+ of NMDA-activated single-channel currents recorded in cell-attached patches.

A and B, single-channel current is plotted as a function of membrane potential. Symbols show means ±s.e.m. when the number of measurements is greater than 2. A, data were obtained from: ○, cell-attached patches with resting [Mg2+]i; ▵, cell-attached patches while the neuron was in the low-Ca2+ extracellular solution but 1-10 min after [Mg2+]i was elevated by a 5 min application of the Mg2++ NMDA + glycine solution; ⋄, inside-out patches in the low-Ca2+ extracellular solution that were excised following recording of cell-attached patch data at resting [Mg2+]i. Numbers of measurements (n) are: ○, 7 or 8 except at −105 mV (n = 3) and +95 mV (n = 1); ▵, 2 or 3 at all potentials; ⋄, 3 except at −83, −23 and 17 mV (n = 2) and at −103 mV (n = 1). Lines show fits of eqn (2) to data points (○ and ▵) or linear regression fitted to data points (⋄). B, data were obtained from cell-attached patches at resting [Mg2+]i in the normal Ca2+ extracellular solution. n = 4 except at 100 mV (n = 3) and 110 mV (n = 2). The line shows the fit of eqn (2) to data points.

Inclusion of 30 μm NMDA + 10 μm glycine in the pipette solution during cell-attached or inside-out recordings typically induced high-frequency single-channel currents over a wide range of pipette potentials (Vpip). These channel openings were identified as NMDA receptor mediated as described in Results. Single-channel conductance measured with inside-out patches was approximately 40 pS, a value less than typical when measured with outside-out patches, but consistent with previous inside-out patch measurements made with a similar pipette [Ca2+] (e.g. Xiong et al. 1998; Lei et al. 1999). Some brief (≤ 1 ms) single-channel openings were observed in cell-attached patches at depolarised membrane potentials when neurons were perfused with the normal Ca2+ extracellular solution. The frequency of non-NMDA receptor channel openings was greatly reduced when neurons were perfused with the low-Ca2+ extracellular solution, which was used in most cell-attached recordings. Non-NMDA receptor channel openings were also largely excluded from analysis by elimination of brief and low-amplitude single-channel currents (see below). Comparison of results from cell-attached patch recordings from neurons perfused with normal Ca2+ and with low-Ca2+ extracellular solutions (Fig. 6) suggested that even in the normal Ca2+ extracellular solution, non-NMDA receptor channel openings did not interfere with our measurements.

The neuronal resting potential (Vrest) was estimated as the Vpip at which NMDA-activated single-channel currents reversed. When neurons were perfused with the normal Ca2+ extracellular solution, the average value of Vrest was −74.4 ± 2.2 mV, in reasonable agreement with the values (around −60 mV) determined under similar conditions by Paoletti & Ascher (1994). NMDA-activated single-channel currents were recorded at pipette potentials (Vpip) from +20 to −180 mV in 20 mV increments during perfusion with normal Ca2+ extracellular solution. When the neuron was perfused with the low-Ca2+ extracellular solution, the average value of Vrest was −3.6 ± 0.9 mV, and single-channel currents were recorded at Vpip values ranging from −100 to +100 mV. The membrane potential of patches (Vm) was calculated as Vm =Vrest − Vpip.

Data analysis

Data were played back through an 8-pole low-pass Bessel filter (Model 902; Frequency Devices, Haverhill, MA, USA) with a corner (−3 dB) frequency of 2 kHz and digitised at 5 kHz with a Digidata 1200 (Axon Instruments) for single-channel analysis. Single-channel current amplitude was determined by fitting open event amplitude histograms (see Fig. 5B) using pCLAMP 6 (Axon Instruments). Events ≤ 1 ms and events of amplitude less than one-half the NMDA receptor main conductance state amplitude were excluded from amplitude histograms. These procedures diminished the influence of non-NMDA receptor channel activity and improved the accuracy of amplitude estimates. Channel openings were identified with a 50 % threshold criterion (Colquhoun & Sigworth, 1995). The procedures of burst analysis were described in Li-Smerin & Johnson (1996b). Briefly, the data acquired with pCLAMP 5 were edited, mainly to eliminate shifts in the baseline, with the Channel Analysis Program (CAP, RC Electronics, Goleta, CA, USA). The mean open time and the frequency of openings were analysed using CAP and a program written by one of the authors (J. W. J.) using the AxoBASIC (Axon Instruments) programming environment. Burst frequency and burst duration were analysed after eliminating brief events (see Results). The mean burst duration was obtained by fitting unbinned data using the maximum likelihood method, and was compensated for the elimination of brief events (Colquhoun & Sigworth, 1995).

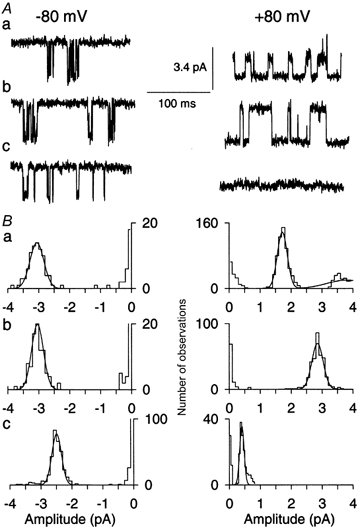

Figure 5. NMDA-activated single-channel currents measured with resting and with elevated [Mg2+]i.

A, recordings of NMDA-activated single-channel currents at −80 mV (left column) and +80 mV (right column) with 30 μm NMDA + 10 μm glycine in the pipette solution. B, amplitude histograms derived from single-channel currents shown in corresponding records in A. a, a cell-attached patch on a neuron with resting [Mg2+]i (approximately 0.35 mm; see Table 2) in the low-Ca2+ extracellular solution; b, an inside-out patch was pulled during continued superfusion with low-Ca2+ extracellular solution; c, a cell-attached patch on a neuron in the low-Ca2+ extracellular solution following elevation of [Mg2+]i (to approximately 2.4 mm; see Fig. 4 and Table 2). Data in a and b are from the same patch; data in c are from a patch on a different cell. The bin width was 0.1 pA in all histograms except in c at +80 mV, where the bin width was 0.05 pA.

Curve fitting and statistics

For the calibration of mag-indo-1, eqn (1) was fitted to data (Fig. 2) using the Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm in GraphPad Prism. Equation (2) was fitted to data from cell-attached patch recordings (Fig. 6) and eqn (4) to data from whole-cell recordings (Fig. 7) using the Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm in SigmaPlot 5.0. Data are presented as means ±s.e.m. Statistical tests were performed with Systat 5 for Windows, and P < 0.05 was set as the significance level.

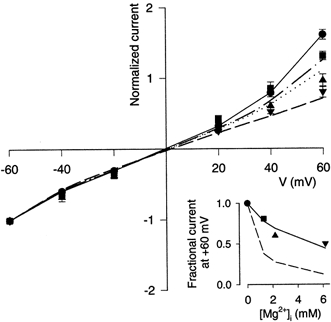

Figure 7. Application of gating hypothesis to inhibition by Mgi2+ of whole-cell current.

Current data are from Fig. 5 of Li-Smerin & Johnson (1996b). Main plot shows mean ±s.e.m. of normalised currents (whole-cell current measured at the indicated membrane potential divided by the absolute value of current measured at −60 mV). Inset shows mean of fractional currents at +60 mV (normalised current in the indicated [Mg2+]i divided by normalised current in 0 Mgi2+). Symbols correspond to the following [Mg2+]i values (mm), which are based on [Mg2+] measurements presented here (Fig. 3): •, 0; ▪, 1.3; ▴, 2.2; ▾, 6.2. Note that the [Mg2+] values calculated in Li-Smerin & Johnson (1996b) (1, 3 and 10 mm in the three Mg2+-containing solutions) were inaccurate. Data for each point from at least 5 cells. Inset: the continuous line is the result of fitting eqn (3) to data points with KRg the only free parameter, yielding KRg = 5.7. The dashed line represents fractional current predictions based solely on the reduction of single-channel current measured with cell-attached patches (Fig. 6). Main plot: eqn (3) with KRg set to 5.7 was used to predict the whole-cell currents at each potential with [Mg2+]i equal to 1.3 mm (dashed and dotted line), 2.2 mm (dotted line) and 6.2 mm (dashed line). Predictions were made by multiplying the value of In,Mg/In,control derived from eqn (3) by the plotted value of normalised current with 0 Mgi2+; this procedure took into account the outward rectification of currents measured with 0 Mgi2+, which is not predicted by eqn (3). Data points with 0 Mgi2+ are connected by the continuous line.

Materials

Cell culture reagents were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA), Gibco Laboratories (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY, USA) and HyClone Laboratories, Inc. (Logan, UT, USA). Mag-indo-1 and mag-indo-1 AM were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA), dissolved in anhydrous DMSO and frozen in aliquots. All other chemicals used for solutions were obtained from Sigma or Aldrich.

RESULTS

[Mg2+]i during whole-cell recording

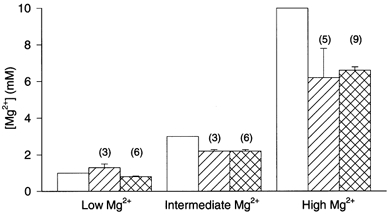

Our first goal was to determine whether the unexpectedly weak inhibition by Mgi2+ of whole-cell NMDA responses was due to a difference between the [Mg2+] in the recording pipette and inside neurons during dialysis. Because the Mg2+-containing pipette solutions we used previously (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996a) also contained EGTA, which acts as a Mg2+ buffer, we calculated the [Mg2+] by subtracting Mg2+ bound to EGTA from total Mg2+. This calculation requires that the EGTA apparent affinity constant for Mg2+ be estimated by extrapolation from published complexation constants, a process that may not yield accurate results. Here instead, we measured in vitro the [Mg2+] in our three pipette solutions using mag-indo-1. The results indicate that the previously calculated values of free [Mg2+] (1 mm in the low, 3 mm in the intermediate, and 10 mm in the high [Mg2+] whole-cell recording solutions) were surprisingly inaccurate (Fig. 3). We then determined [Mg2+] inside neurons during whole-cell dialysis with each pipette solution using mag-indo-1. These results show that the neuronal [Mg2+] was significantly higher than pipette [Mg2+] when neurons were dialysed with the low Mg2+ whole-cell recording solution (1.3 ± 0.2 mmin situ; 0.8 ± 0.05 mmin vitro, P = 0.01; Fig. 3 left). There were no significant differences between neuronal and pipette [Mg2+] during dialysis with the intermediate (2.2 ± 0.08 mmin situ; 2.2 ± 0.08 mmin vitro; Fig. 3 middle) or high (6.2 ± 1.6 mmin situ; 6.6 ± 0.2 mmin vitro, P = 0.60; Fig. 3 right) Mg2+ whole-cell recording solutions. These results indicate that neuronal regulation of [Mg2+] during whole-cell recording cannot explain the weak inhibition of NMDA responses.

Figure 3. Comparison of [Mg2+] estimated using three different approaches.

Estimates of [Mg2+] in the low (left three columns), intermediate (middle three columns) and high (right three columns) Mg2+ whole-cell recording solutions (Table 1) are shown. □: calculated free [Mg2+] in the whole-cell recording solutions based on extrapolated EGTA complexation constants (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996a).  : free in situ[Mg2+] based on the steady-state value of R measured during whole-cell recording with pipettes filled with each whole-cell recording solution; R value was converted to the plotted [Mg2+] using the in situ calibration curve (Fig. 2).

: free in situ[Mg2+] based on the steady-state value of R measured during whole-cell recording with pipettes filled with each whole-cell recording solution; R value was converted to the plotted [Mg2+] using the in situ calibration curve (Fig. 2).  : free in vitro[Mg2+] based on the value of R measured with each whole-cell recording solution in the recording chamber; the R value was converted to the plotted [Mg2+] using the in vitro calibration curve (Fig. 2). Columns for the in situ and in vitro[Mg2+] show means ±s.e.m.; numbers of experiments are shown in parentheses.

: free in vitro[Mg2+] based on the value of R measured with each whole-cell recording solution in the recording chamber; the R value was converted to the plotted [Mg2+] using the in vitro calibration curve (Fig. 2). Columns for the in situ and in vitro[Mg2+] show means ±s.e.m.; numbers of experiments are shown in parentheses.

Effects of Mgi2+ on the NMDA receptor in intact neurons

Our next goal was to test an alternative hypothetical explanation for why Mgi2+ inhibits mean patch current more effectively than whole-cell current: patch excision may cause a modification of the NMDA receptor that results in the open channel binding Mgi2+ with higher affinity. To achieve this goal, we first measured the [Mg2+]i in intact neurons using mag-indo-1 AM, and then examined the effects of this measured [Mg2+]i on single-channel activity using cell-attached recordings in separate experiments.

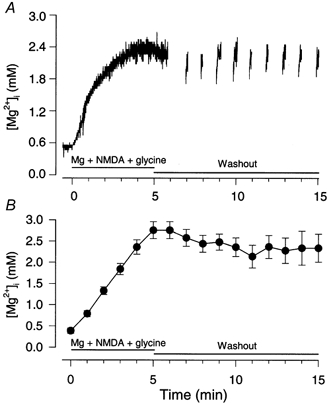

Measurements of [Mg2+]i in intact neurons

[Mg2+]i in intact neurons bathed in control extracellular solution measured with mag-indo-1 AM was 0.35 ± 0.01 mm (n = 110; Table 2). This value is somewhat lower than the value reported by Brocard et al. (1993) for neurons (0.6 mm) obtained with magfura-2 and the average values obtained with diverse techniques in several types of mammalian cells (0.5–0.6 mm; for review see Romani & Scarpa, 1992). The difference may be related to the approaches used for measurements. For example, we employed the in situ calibration curve that we measured for mag-indo-1 (Fig. 2), a procedure that was not used in other studies. In order to study channel block by Mgi2+ in intact neurons at a second [Mg2+]i, we made similar measurements with the control extracellular solution being replaced by the Mg2++ NMDA + glycine solution (see Methods). We expected that the application of this solution would elevate [Mg2+]i because extracellular Mg2+ (Mgo2+) has been reported to permeate NMDA receptor channels in the absence of other permeant extracellular cations (Stout et al. 1996). When we superfused neurons with the Mg2++ NMDA + glycine solution, [Mg2+]i increased from 0.35 to 2.8 ± 0.2 mm (n = 11) by the end of a 5 min application, supporting the conclusions of Stout et al. (1996). The elevated [Mg2+]i remained reasonably stable for an extended period after washout of the Mg2++ NMDA + glycine solution with the control extracellular solution: [Mg2+]i was at 91 % of the peak value 5 min after washout, and at 83 % 10 min after washout (Fig. 4, Table 2). The mean value of [Mg2+]i during the 10 min washout period, 2.4 mm, was used in the following analysis of block by Mgi2+ in intact neurons.

Table 2.

Measurements of [Mg2+] in intact neurons

| Condition | [Mg2+]i (mm) | n |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.35 ± 0.01 * | 110 |

| High Mg2+ (5 min) | 2.76 ± 0.17 † | 11 |

| Washout (6–10 min) | 2.52 ± 0.07 ‡ | 10 |

| Washout (11–15 min) | 2.28 ± 0.13 § | 8 |

Measurements obtained with the control extracellular solution.

Measurements obtained 5 min after the start of the application of the Mg2+ + NMDA + glycine solution (91 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 10 mM Hepes, 100 μM NMDA, 10 μM glycine).

Mean of measurements during the first 5 min after washout of the Mg2++ NMDA + glycine solution (see Fig. 4).

Mean of measurements during the second 5 min after washout of the Mg2++ NMDA + glycine solution. All [Mg2+]i measurements are means ± S.E.M.

Figure 4. Persistent increase in [Mg2+]i by influx of Mg2+ through NMDA-activated channels.

[Mg2+]i in intact neurons was calculated from the value of R based on the in situ calibration curve (Fig. 2). [Mg2+]i was raised by perfusion of the neurons with Mg2++ NMDA + glycine solution (91 mm MgCl2, 2 mm EGTA, 10 mm Hepes, 100 μm NMDA and 10 μm glycine). A 5 min application of Mg2++ NMDA + glycine solution was followed by a 10 min wash with the control extracellular solution (Washout). A, an example of the increase in [Mg2+]i upon application of Mg2++ NMDA + glycine solution and during the washout period. [Mg2+]i at time 0 was measured during perfusion of the control solution immediately before application of Mg2++ NMDA + glycine. For this illustration, the fluorescence signal was sampled continuously during the first 6 min and then every 1 min for the remaining 9 min. B, means ±s.e.m. of data pooled from 11 neurons during application of Mg2++ NMDA + glycine and from at least 6 cells during the washout period. The [Mg2+]i was measured every minute during the application of Mg2++ NMDA + glycine and during the washout period. Data points are connected by a straight line.

Block by Mgi2+ of NMDA-activated single-channel currents recorded in cell-attached and inside-out patches

To determine the sensitivity to Mgi2+ of the open channel of NMDA receptors in intact neurons, we recorded NMDA-activated single-channel currents as a function of membrane potential in cell-attached patches. Channel openings were identified as NMDA receptor mediated based on the following observations: (1) omission of NMDA + glycine from the pipette solution (n = 6) or addition of 100 μm d,l-aminophosphonovalerate (APV) with the agonists (n = 4) largely eliminated single-channel activity at resting potential; (2) the amplitude of the single-channel currents measured with Vpip = 0 mV was consistent with the results of previous cell-attached studies (Legendre et al. 1993; Paoletti & Ascher, 1994; Kleckner & Pallotta, 1995); (3) the mean open time (1.70 ms) and burst duration (3.63 ms) values we measured using the approach of Paoletti & Ascher (1994) at a comparable membrane potential (around −60 mV) were similar to the values they measured (1.88 and 3.75 ms, respectively); these values are also in reasonable agreement with measurements by Gibb & Colquhoun (1992) from cell-attached and inside-out patches of mean open time (1.22 ms) and burst duration (2.30 ms).

Examples of single-channel current records and corresponding amplitude histograms recorded in the low-Ca2+ extracellular solution are presented in Fig. 5. The amplitude of single-channel currents obtained from the cell-attached patch with resting [Mg2+]i was smaller at +80 than at −80 mV (Fig. 5Aa and Ba). This voltage-dependent reduction in the current amplitude was removed when the patch was excised and superfused with the low-Ca2+ extracellular solution (Fig. 5Ab and Bb). The contrast in the single-channel current amplitude at +80 mV between the cell-attached and cell-free inside-out patches suggests that resting Mgi2+ had blocked the NMDA receptor channel in the intact neuron. If this block was due to the binding of Mgi2+ inside the channel pore, then the degree of the block should be enhanced with an elevated [Mg2+]i. This notion was supported by the striking further reduction in single-channel current amplitude observed at positive potentials (Fig. 5Ac and Bc) when [Mg2+]i in intact neurons was increased by Mg2+ influx through NMDA receptor channels (see Fig. 4 and Table 2). The elevated [Mg2+]i also induced a moderate decrease in the single-channel current at negative potentials (Fig. 5Ac and Bc). The voltage-dependent reduction of single-channel current amplitude in cell-attached patches following elevation of [Mg2+]i was removed by subsequent excision of an inside-out patch into the low-Ca2+ extracellular solution (data not shown). These data demonstrate that Mgi2+ blocks the channel of NMDA receptors in intact neurons.

Comparison of the sensitivity to channel block by Mgi2+ of NMDA receptors in intact neurons and in outside-out patches

We next tested the hypothesis that Mgi2+ blocks the open channel of NMDA receptors with higher affinity following patch excision. Channel block of NMDA receptors before patch excision (in cell-attached patches) and after patch excision (in outside-out patches) was compared quantitatively with a model in which Mgi2+ inhibits single-channel current by occluding the conducting pathway (Johnson & Ascher, 1990; Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996a). In this model, Mgi2+ appears to decrease single-channel current because transitions between the blocked and the unblocked states are so rapid that they cannot be resolved. The voltage dependence of block in this model results from the requirement that Mgi2+ traverses part of the electric field of the membrane to reach its blocking site in the channel. The following equation was previously derived (Johnson & Ascher, 1990) from this model:

| (2) |

where i(Vm) is the measured single-channel current at any membrane potential, Vm, in the presence of [Mg2+]i, g is the single-channel conductance in the absence of [Mg2+]i, Vr is the reversal potential, K0 is the dissociation constant of Mgi2+ at Vm = 0, and V0 is a parameter that reflects the voltage dependence of block by Mgi2+. Thus, K0 characterises the affinity and V0 the voltage dependence of block by Mgi2+.

To quantify Mgi2+ block while minimising the number of free parameters, we fitted eqn (2) to single-channel current data from cell-attached patches with V0 set equal to 36.8 mV, the value previously measured in outside-out patches (Johnson & Ascher, 1990). [Mg2+]i was set equal to the value measured in the appropriate experiments on intact neurons (Table 2), and g and K0 were free parameters. We fitted three sets of data obtained from cell-attached patches (Fig. 6). Two of the data sets were obtained at the resting [Mg2+]i, one in the low-Ca2+ (Fig. 6A) and the other in the normal Ca2+ (Fig. 6B) extracellular solution. These two conditions were compared to determine whether non-NMDA receptor channel openings, which were greatly reduced in frequency by use of low-Ca2+ extracellular solution, significantly affected our results. The third data set was obtained in the low-Ca2+ extracellular solution after elevation of [Mg2+]i. With [Mg2+]i set at 0.35 mm (Table 2), fitting of eqn (2) to the pooled data obtained at the resting [Mg2+]i and in the low-Ca2+ extracellular solution (Fig. 6A) yielded 3.3 ± 0.3 mm for K0. Use of the same approach to fit the pooled data obtained at the resting [Mg2+]i and in the normal Ca2+ extracellular solution (Fig. 6B) yielded 3.8 ± 0.6 mm for K0. With [Mg2+]i set at 2.4 mm (Table 2), fitting of eqn (2) to the pooled data obtained after [Mg2+]i was elevated by a 5 min application of the Mg2++ NMDA + glycine solution yielded 3.0 ± 0.6 mm for K0 (Fig. 6A). Since these three values were not significantly different, the average, 3.4 ± 0.2 mm, is shown in Table 3 as the value of K0 for Mgi2+ block in intact neurons.

Table 3.

Dissociation constants of inhibition by Mgi2+ of NMDA-activated currents

| Type of current | K0 (mm) |

|---|---|

| Cell-attached patch single-channel current | 3.4 ± 0.2* |

| Outside-out patch single-channel current | 4.1 ± 0.6† |

| Type of current | K0,app (mm) |

| Outside-out patch mean current | 5.9‡ |

| Whole-cell current | 19.5§ |

Mean ± S.E.M. of the results from fitting the i—V relation in Fig. 6 with [Mg2+]i = 0.35 mM (Table 2).

Results from previous (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996a,b) analysis of inhibition by Mgi2+ of outside-out patch single-channel current († mean ± S.E.M.) and mean patch current (‡), but with [Mg2+] in each of the pipette solutions set to the values derived here from in vitro measurements of [Mg2+] (Fig. 3).

Results from previous (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996a,b) analysis of inhibition by Mgi2+ of outside-out patch single-channel current († mean ± S.E.M.) and mean patch current (‡), but with [Mg2+] in each of the pipette solutions set to the values derived here from in vitro measurements of [Mg2+] (Fig. 3). K0,app values were calculated as K0KRg.

Results from previous (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b) analysis of inhibition by Mgi2+ of whole-cell current (see inset in Fig. 7), but with [Mg2+] in each of the whole-cell recording solutions set to the values derived here from in situ measurements (Fig. 3). K0,app values were calculated as K0KRg.

The similarity in the values of K0 in the low-Ca2+ and the normal Ca2+ extracellular solutions suggests that the presence of non-NMDA receptor channel openings did not interfere with our results. The accuracy of the fits shown in Fig. 6 and the consistency in the values of K0 in resting and elevated [Mg2+]i supports the validity in intact neurons of the model used to derive eqn (2).

The results shown in Fig. 6 were next compared with our previous measurements of channel block by Mgi2+ of NMDA receptors in outside-out patches (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996a,b). To allow comparison of the two data sets, the outside-out patch data were refitted after being corrected for inaccuracies in our previous estimates of the free [Mg2+] in the whole-cell recording solutions. Based on the results of in vitro mag-indo-1 measurements of free [Mg2+] (Fig. 3), we refitted the outside-out patch single-channel i–V relations in Li-Smerin & Johnson (1996a) using 0.8 mm (low), 2.2 mm (intermediate) and 6.6 mm (high) as the free [Mg2+] values. As a result of these corrections in [Mg2+]i, the value of K0 obtained from curve fitting of the i–V relation of outside-out patches was 4.1 ± 0.6 mm, which is lower than the previous estimate (7.8 mm) because of the lower estimates of the free [Mg2+] values in the whole-cell recording solutions. The value of 4.1 ± 0.6 mm is not significantly different from the value of 3.4 ± 0.2 mm obtained in intact neurons (Table 3, Student's two-tailed t test). These data suggest that NMDA receptors in intact neurons are at least as sensitive to block of single-channel current by Mgi2+ as receptors in outside-out patches.

Effects of Mgi2+ on gating of NMDA receptors

The data presented above demonstrate that the ability of Mgi2+ to inhibit mean outside-out patch current more effectively than whole-cell current cannot be attributed to either: (1) [Mg2+]i regulation during whole-cell recording (Fig. 3); or (2) a patch excision-induced increase in the affinity of Mgi2+ for the open channel of the NMDA receptor (Fig. 6, Table 3). An alternative hypothesis is suggested by the observation in outside-out patches that Mgi2+ binding modifies channel gating of the NMDA receptor, resulting in stabilisation of the open state of the channel (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b). This effect of Mgi2+ causes an increase in the frequency of channel opening (quantified as burst frequency), partially compensating for the inhibition of current due to channel block. If Mgi2+ affects channel gating of the NMDA receptor in intact neurons more strongly than NMDA receptors in outside-out patches, then the observed differential inhibition of steady-state responses between these two preparations could result.

To test this ‘gating’ hypothesis, we first examined the effect of Mgi2+ on the channel gating of the NMDA receptor in cell-attached patches.

Effect of Mgi2+ on channel gating of NMDA receptors in intact neurons

The effects of Mgi2+ on the channel gating of NMDA receptors were previously characterised by measuring the frequency and duration of bursts of channel openings to minimise potential errors relating to the extremely fast kinetics of Mgi2+ block (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996a,b). We found that Mgi2+ caused a small increase the frequency of channel bursts of the NMDA receptor in outside-out patches (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b). To determine whether Mgi2+ has the same effect on NMDA receptor channel gating in intact neurons, we measured the burst frequency and burst duration in cell-attached patches. Cell-attached patch recordings made at Vm values of +60 and −60 mV, with 20–60 s recording times at each potential, and at the resting [Mg2+]i, were used to maximise the reliability of the results. Records at intermediate potentials or during elevation of [Mg2+]i were not used because under these conditions the small single-channel current and large open-channel noise caused by Mgi2+ precluded accurate measurement of burst parameters. Only data obtained in the low-Ca2+ extracellular solution were used to minimise interference from non-NMDA receptor channel openings at +60 mV. Burst analysis was performed using the procedure we developed previously to ignore 50 % channel threshold crossings caused by open-channel noise, a particular problem in the presence of Mgi2+. This procedure, which involved elimination of closures of ≤ 1 ms and then of openings of ≤ 0.4 ms (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b), reduced the apparent number of openings at +60 mV by 80 %.

The burst frequency and burst duration values measured at +60 mV were normalised to the values obtained at −60 mV for each cell-attached patch in order to pool the data from different neurons. The normalised burst frequency (fb) was 2.1 ± 0.2 (n = 4) and the normalised burst duration (tb) was 1.6 ± 0.1 (n = 4). The product fbtb was 3.3 ± 0.2 in cell-attached patches. This value was significantly larger (P < 0.02, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's HSD test for post hoc comparisons) than the fbtb values obtained in outside-out patches (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b) either with 0 Mgi2+ (1.9 ± 0.2; n = 3) or with 0.8 mm Mgi2+ (2.3 ± 0.1; n = 3). Previous data suggest that, in the absence of Mgi2+, the value of fbtb for NMDA receptors is either similar in outside-out patches and in intact neurons or is larger in outside-out patches (Nowak & Wright, 1992; Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b). Thus, the observation that fbtb is larger in cell-attached patches (where [Mg2+]i is 0.35 mm; Table 2) than in outside-out patches with 0 Mgi2+ suggests that Mgi2+ stabilises the channel open state of NMDA receptors in intact neurons. The observation that fbtb is larger in cell-attached patches than in outside-out patches with 0.8 mm Mgi2+ suggests that Mgi2+ stabilises the channel open state more effectively in intact neurons than in outside-out patches.

This burst analysis of cell-attached patch data supports the gating hypothesis. Further testing of the gating hypothesis with cell-attached patch data was hindered by our inability to lower [Mg2+]i in intact cells, or to perform burst analysis at elevated [Mg2+]i. We instead evaluated the plausibility of the gating hypothesis by determining in the next two sections: (1) whether the gating hypothesis is capable of reproducing quantitatively the voltage and [Mg2+]i dependence of our previously published whole-cell data (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b); and (2) whether the increase in fb and tb observed in cell-attached patches at the resting [Mg2+]i is sufficient to explain the difference between inhibition by Mgi2+ of single-channel and whole-cell currents.

Consistency of gating hypothesis with voltage- and [Mg2+]i-dependence of inhibition of whole-cell currents

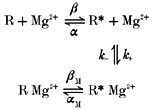

To determine whether the gating hypothesis is quantitatively consistent with the observed properties of Mgi2+ inhibition of whole-cell currents, we used the following four-state model of Mgi2+ action, which was introduced in Li-Smerin & Johnson (1996b):

|

Model(1) |

R, R*, R*Mg2+ and R Mg2+ are the fully liganded receptors in the closed, open, open blocked and closed blocked states, respectively. α and β represent the indicated rate constants of channel gating. The values of the rate constants for block (k+) and unblock (k−) of Mgi2+ were taken from Li-Smerin & Johnson (1996a). Because the equilibrium between the open and closed channel states can change as a result of Mgi2+ binding in model (1), it can be used to test the gating hypothesis. The following form of the equation derived in Li-Smerin & Johnson (1996b) from model (1) can be applied to normalised whole-cell currents:

In this equation, In is the steady-state NMDA-activated current at membrane potential Vm normalised to the current measured at −60 mV in the presence (In,Mg) or absence (In,control) of Mgi2+, K0 is the dissociation constant of Mgi2+ at 0 mV, and KRg is a parameter that reflects the change in channel gating induced by Mgi2+ binding. Quantitatively, KRg =(1 + α/β)/(1 + αM/βM), where α is the channel closing rate, β is the channel opening rate, and αM and βM are the corresponding rates when the channel is blocked by Mgi2+. A value of greater than 1 for KRg would indicate that Mgi2+ binding stabilises the open state of the channel of the NMDA receptor (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b).

The following predictions can be derived from the gating hypothesis: (1) fitting of eqn (3) to whole-cell data should provide a value of KRg substantially greater than the value derived from fits to data from outside-out patches (1.4; Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b), and (2) a single value of KRg should provide adequate fits to whole-cell data at all voltages and [Mg2+]i values. These predictions were tested by first fitting eqn (3) to the values of fractional block of whole-cell current at +60 mV measured with three different concentrations of Mgi2+ (inset, Fig. 7). The values of fractional current were taken from Li-Smerin & Johnson (1996b) and the [Mg2+]i during whole-cell recording from measurements reported here (Fig. 3). By using the value of K0 derived from cell-attached patches (3.4 mm; Table 3), the only free variable in eqn (3) was KRg. The fit provided a value of 5.7 for KRg, which would raise the apparent dissociation constant of Mgi2+ at 0 mV in whole-cell experiments to 19.5 mm (Table 3). Equation (3) was then used with no free variables to predict the fractional inhibition by Mgi2+ of NMDA-activated whole-cell current over a range of membrane potentials. Considering the simplicity of model (1), the predictions appear in reasonable agreement with the data (Fig. 7), in support of the gating hypothesis.

Consistency of Mgi2+-dependent increase in fbtb and weak inhibition of whole-cell currents

In the previous two sections we determined: (1) in intact neurons, fbtb equals 3.3 at +60 mV when [Mg2+]i equals 0.35 mm, indicating that Mgi2+ strongly stabilises the open state; (2) the disparity between inhibition by Mgi2+ of single-channel and whole-cell currents can be explained if Mgi2+ stabilises the open state of NMDA receptors by a factor of 5.7 as measured by KRg. As a final test of the gating hypothesis, we determine here that these two results are mutually consistent.

To relate KRg to fbtb, we first use eqn (3) to predict that with [Mg2+]i = 0.35 mm, K0 = 3.4 mm, and KRg = 5.7, In,Mg/In,control should equal 0.92 in whole-cell experiments at +60 mV. This means that at 0.35 mm Mgi2+, the fits shown in Fig. 7 predict only an 8 % inhibition by Mgi2+ of normalised whole-cell current at +60 mV. The value of In,control was measured as 1.6 (Fig. 7), yielding a predicted value of In,Mg of 1.5 at 0.35 mm Mgi2+. In contrast, in,Mg measured in cell-attached patches at the resting [Mg2+]i (Fig. 6) is 0.58 at +60 mV. The identity I =NPopeni can be used to determine the value of fbtb (which equals normalised Popen) needed to explain this difference. N, which is voltage independent, equals 1 following normalisation. The required value of fbtb then is 1.5/0.58=2.6. The value of fbtb measured in cell-attached patches (3.3) was therefore more than adequate to account for the weak inhibition by Mgi2+ of whole-cell currents relative to mean patch currents. The effect of Mgi2+ on gating of NMDA receptors in cell-attached patches is thus adequate to explain the disparity between inhibition by Mgi2+ of single-channel and whole-cell currents.

DISCUSSION

Control of [Mg2+]i during whole-cell recordings

One goal of this study was to determine why Mgi2+ inhibits whole-cell NMDA-activated currents less effectively than mean currents of outside-out patches. One possible explanation is that [Mg2+]i during whole-cell recording is maintained below the [Mg2+]i in the pipette solution (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b). Neurons, like many other cell types, have powerful mechanisms to regulate free [Mg2+]i at 5–10 % of total [Mg2+]i (for reviews see Flatman, 1991; Romani & Scarpa, 1992). For example, the block of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in PC12 cells by residual Mgi2+ during whole-cell recording can only be relieved by dialysing cells with Mg2+ chelators for at least 20 min (Sands & Barish, 1992). If some of the cellular regulatory mechanisms remain functional during whole-cell dialysis, then the effectiveness with which Mgi2+ inhibited whole-cell current could have been underestimated. We previously observed that inclusion of EGTA in the pipette solution as a Mg2+ buffer enhanced the inhibition by Mgi2+, suggesting that an exogenous Mg2+ buffer can partially overcome cellular regulation of [Mg2+]i (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b). Our results from fluorescence measurements, however, show that [Mg2+]i measured during whole-cell recordings was nearly the same as the [Mg2+] of the pipette solution. Furthermore, inhibition by Mgi2+ of whole-cell currents of neurons and of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected with NR1/NR2A or NR1/NR2B receptors are not significantly different (Li-Smerin et al. 2000). Since CHO cells are compact and have no neurites, [Mg2+]i is likely to be maintained at the pipette [Mg2+]. These results contradict the hypothesis that the relatively ineffective inhibition by Mgi2+ of whole-cell current was due to inadequate control of [Mg2+]i during whole-cell recordings.

Two procedures were performed to ensure the accuracy of measurements of [Mg2+] in dialysed neurons, and comparisons of pipette and neuronal [Mg2+]: (1) in situ calibration of mag-indo-1; and (2) in vitro mag-indo-1 measurements of [Mg2+] in the EGTA-buffered whole-cell recording solutions. The in vitro measurements of [Mg2+] in the whole-cell recording solutions indicated that the free [Mg2+] in EGTA-containing solutions cannot be accurately estimated using published complexation constants for EGTA and Mg2+.

Affinity of Mgi2+ for open channel of NMDA receptors in intact neurons

A second hypothesis that could explain the difference in Mgi2+ inhibition of whole-cell and excised patch experiments is that patch excision modifies the affinity of Mgi2+ for the open channel of NMDA receptors. To test this possibility, we determined the affinity of Mgi2+ for the open channel of NMDA receptors in intact neurons using cell-attached recording. Mgi2+ blocked the NMDA receptor channel in cell-attached patches in a voltage- and [Mg2+]-dependent manner. The values of K0 and V0 obtained from cell-attached and outside-out patches are similar, suggesting that the affinity of Mgi2+ for the open channel of NMDA receptors was not modified by patch excision. Therefore, the difference between inhibition by Mgi2+ of NMDA responses in outside-out patch and in whole-cell preparations cannot be attributed to a difference in the affinity of Mgi2+ for the open channel of NMDA receptors.

One of the benefits of the results of this study is that they permit the measurement of the [Mg2+]i of cells expressing NMDA receptors using cell-attached recordings. Based on our cell-attached recording results, the voltage and [Mg2+]i dependence of the amplitude of single-channel NMDA-activated current is:

Fitting this equation to NMDA receptor i–Vm relations measured with a cell-attached patch and with [Mg2+]i, Vr and g as free parameters can be used to measure [Mg2+]i. A potential concern with this approach is that there may be intracellular ions other than Mgi2+ that can block the channel of NMDA receptors and cause rectification of NMDA receptor i–Vm relations. However, the similarity of the values of K0 derived from outside-out patch data and cell-attached patch data (Table 3) argues that Mg2+ is the predominant intracellular ion responsible for NMDA receptor i–Vm curve rectification.

The advantages of i–Vm curve-based estimates of [Mg2+]i include: (1) [Mg2+]i can be estimated without interference from intracellular Ca2+, which causes only slight channel block of NMDA receptors even at 1 mm (Johnson & Ascher, 1990); (2) the approach is minimally invasive, because the cytoplasm is unaffected by a fluorescent dye or transmembrane electrode.

Although the affinity of Mgi2+ for the open channel of NMDA receptors is not influenced by patch excision, there nevertheless may be endogenous factors that regulate the open-channel affinity of Mgi2+. Permeant ions, for example, profoundly affect the affinity, voltage dependence and kinetics of extracellular Mg2+ block through binding to sites near the extracellular entrance to the channel of NMDA receptors (Antonov & Johnson, 1999; Zhu & Auerbach, 2001). An intracellular permeant ion binding site has also been identified (Antonov et al. 1998), suggesting the possibility that permeant ions may affect block by Mgi2+. Many endogenous factors that might regulate Mgi2+ block remain to be investigated.

Effect of Mgi2+ on channel gating of NMDA receptors in intact neurons

We previously showed that Mgi2+ weakly stabilises the channel open state of NMDA receptors in outside-out patches (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b). Based on this observation, we tested a third hypothesis (the ‘gating hypothesis’) to explain the differential inhibition by Mgi2+ in whole cells and excised patches: that Mgi2+ powerfully stabilises the channel open state of NMDA receptors in intact neurons, but that the effect is weakened by patch excision. We first made burst measurements in cell-attached patches and found that Mgi2+ does stabilise the channel open state of NMDA receptors in cell-attached patches more powerfully than NMDA receptors in outside-out patches. We then fitted a model of the gating effects of Mgi2+ to whole-cell data. The model indicated that the gating hypothesis is consistent with the voltage and Mgi2+ dependence of whole-cell currents provided that the Mgi2+-induced stabilisation of the open state is attenuated fourfold by patch excision. Finally, we integrated the model with our other electrophysiological and fluorescence measurements to compare the magnitudes of the effects of Mgi2+ on burst parameters and on whole-cell currents. This comparison showed that the measured effect of Mgi2+ on the gating of NMDA receptors in intact cells is powerful enough to explain the differential inhibition by Mgi2+ of single-channel and whole-cell currents.

Implications of Mgi2+ modulation of NMDA receptors

Block of NMDA responses by Mgi2+ is less likely than block by Mgo2+ to be important under physiological conditions because Mgi2+ blocks with high affinity only at very positive membrane potentials. In addition, the effect of Mgi2+ on channel gating acts to weaken the inhibition by Mgi2+ of NMDA responses. These findings underscore the danger in extrapolating between measurements of single-channel current block and whole-cell current inhibition; channel blockers generally influence the gating of NMDA receptors (e.g. Koshelev & Khodorov, 1992; Benveniste & Mayer, 1995; Antonov & Johnson, 1996; Dilmore & Johnson, 1998; Sobolevsky et al. 1999), rendering the extrapolation inaccurate.

The interaction between Mgi2+ and NMDA receptors nevertheless is a useful experimental tool in several respects: (1) Mg2+ can be used to probe the structure, function and gating of NMDA receptors from the inside as well as the outside of the membrane (e.g. Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996a,b; Kupper et al. 1996; Wollmuth et al. 1998); (2) block by Mgi2+ can be used to measure [Mg2+]i (see above); (3) because modulation of NMDA receptor gating by Mgi2+ is strongly affected by patch excision, Mgi2+ may be used to study interactions between intracellular constituents and NMDA receptor properties.

The majority of properties of NMDA receptors that have been compared in intact cells and in excised patches have been found to be unaffected by patch excision (e.g. Lester et al. 1990; Gibb & Colquhoun, 1992). However, several properties of NMDA receptors have been found to be modified by patch excision in addition to the effect of Mgi2+ on channel gating, including channel open probability (Rosenmund et al. 1995), single-channel conductance (Clark et al. 1997), glycine-insensitive desensitisation (Sather et al. 1990, 1992; Benveniste et al. 1990) and mechanosensitivity (Paoletti & Ascher, 1994). These changes in NMDA receptor properties could result from either loss of diffusible intracellular constituents or disruption of interactions between NMDA receptors and immobile intracellular proteins. It seems unlikely that loss of diffusible intracellular constituents (such as ATP (MacDonald et al. 1989) or calmodulin (Ehlers et al. 1996)) are responsible for the change in Mgi2+ influence on channel gating induced by patch excision: inhibition by Mgi2+ of whole-cell NMDA responses recorded with a simple intracellular solution remains weak over at least a 30 min recording period (Li-Smerin & Johnson, 1996b). The more likely explanation is loss of interaction of NMDA receptors with intracellular proteins that may not be diffusible, such as proteins that contain the PDZ domain (for review see Dingledine et al. 1999). Inhibition by Mgi2+ during whole-cell recordings is as weak in CHO cells tranfected with NMDA receptors as in neurons (Li-Smerin et al. 2000). Thus, if patch excision affects inhibition by Mgi2+ by disrupting NMDA receptor interactions with another non-diffusible protein, that protein must not be specific to the nervous system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Juliann Jaumotte for technical assistance and Dr Jerry Wright for providing software for the analysis of single-channel data. This work was supported by NIMH grants MH45817 and MH00944 to J.W.J., by NIMH Training grant T32 MH18273 to Y.L.S., and by NIH grant 32385 to E.S.L.

References

- Antonov SM, Gmiro VE, Johnson JW. Binding sites for permeant ions in the channel of NMDA receptors and their effects on channel block. Nature Neuroscience. 1998;1:451–461. doi: 10.1038/2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonov SM, Johnson JW. Voltage-dependent interaction of open channel blocking molecules with gating of NMDA receptors in rat cortical neurons. Journal of Physiology. 1996;493:425–445. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonov SM, Johnson JW. Permeant ion regulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor channel block by Mg2+ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;96:14571–14576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste M, Clements J, Vyklicky L, Mayer ML. A kinetic analysis of the modulation of N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptors by glycine in mouse cultured hippocampal neurons. Journal of Physiology. 1990;428:333–357. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolino M, Vicini S. Voltage-dependent block by strychnine of N-methyl-D-aspartic acid-activated cationic channels in rat cortical neurons in culture. Molecular Pharmacology. 1988;34:98–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpied TA, Boeckman FA, Aizenman E, Johnson JW. Trapping channel block of NMDA-activated receptors by amantadine and memantine. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;77:309–323. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocard JB, Rajdev S, Reynolds IJ. Glutamate-induced increase in intracellular free Mg2+ in cultured cortical neurons. Neuron. 1993;11:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW. Calcium: still center-stage in hypoxic-ischemic neuronal death. Trends in Neurosciences. 1995;18:58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark BA, Farrant M, Cull-Candy SG. A direct comparison of the single-channel properties of synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:107–116. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00107.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D, Sigworth FJ. Fitting and statistical analysis of single-channel records. In: Sakmann B, Neher E, editors. Single-Channel Recording. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 483–585. [Google Scholar]

- Dilmore JG, Johnson JW. Open channel block and alteration of N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor gating by an analog of phencyclidine. Biophysical Journal. 1998;75:1801–1816. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77622-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacological Reviews. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers MD, Zhang S, Bernhardt JP, Huganir RL. Inactivation of NMDA receptors by direct interaction of calmodulin with the NR1 subunit. Cell. 1996;84:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatman PW. Mechanisms of magnesium transport. Annual Review of Physiology. 1991;53:259–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.001355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb AJ, Colquhoun D. Activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors by L-glutamate in cells dissociated from adult rat hippocampus. Journal of Physiology. 1992;456:143–179. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugland RP. Handbook of Fluorescent Probes and Research Chemicals. Eugene, OR, USA: Molecular Probes; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JW, Ascher P. Voltage-dependent block by intracellular Mg2+ of N-methyl-D-aspartate-activated channels. Biophysical Journal. 1990;57:1085–1090. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82626-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleckner NW, Pallotta BS. Burst kinetics of single NMDA receptor currents in cell-attached patches from rat brain cortical neurons in culture. Journal of Physiology. 1995;486:411–426. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshelev SG, Khodorov BI. Tetraethylammonium and tetrabutylammonium as tools to study NMDA channels of neuronal membrane. Biologicheskie Membrany. 1992;9:1365–1369. [Google Scholar]

- Kupper J, Ascher P, Neyton A. Probing the pore region of recombinant N-methyl-D-aspartate channels using external and internal magnesium block. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:8648–8653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupper J, Ascher P, Neyton A. Internal Mg2+ block of recombinant NMDA channels mutated within the selectivity filter and expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.001bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P, Rosenmund C, Westbrook GL. Inactivation of NMDA channels in cultured hippocampal neurons by intracellular calcium. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:674–684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00674.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei S, Lu W-Y, Xiong Z-G, Orser BA, Valenzuela CF, Macdonald JF. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-induced feed-forward inhibition of excitatory transmission between hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:30617–30623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester RA J, Clements JD, Westbrook GL, Jahr CE. Channel kinetics determine the time course of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic currents. Nature. 1990;346:565–567. doi: 10.1038/346565a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy LA, Murphy E, Raju B, London RE. Measurement of cytosolic free magnesium ion concentration by 19F NMF. Biochemistry. 1988;27:4041–4048. doi: 10.1021/bi00411a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Smerin Y, Aizenman E, Johnson JW. Inhibition by intracellular Mg2+ of recombinant N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2000;292:1104–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Smerin Y, Johnson JW. Kinetics of the block by intracellular Mg2+ of the NMDA-activated channel in cultured rat neurons. Journal of Physiology. 1996a;491:121–135. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Smerin Y, Johnson JW. Effects of intracellular Mg2+ on channel gating and steady-state responses of the NMDA receptor in cultured rat neurons. Journal of Physiology. 1996b;491:137–150. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald JF, Mody I, Salter MW. Regulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors revealed by intracellular dialysis of murine neurones in cultures. Journal of Physiology. 1989;414:17–34. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathie A, Colquhoun D, Cull-Candy SG. Rectification of currents activated by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat sympathetic ganglion neurons. Journal of Physiology. 1990;427:625–655. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RG, Davis S, Butcher SP. Hippocampal synaptic plasticity and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors: a role in information storage. In: Baudry M, Davis JL, editors. Long-term Potentiation: a Debate of Current Issues. Cambridge, USA: MIT Press; 1991. pp. 27–300. [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. The charge carried by single-channel currents of rat cultured muscle cells in the presence of local anaesthetics. Journal of Physiology. 1983;339:663–687. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak LM, Wright JM. Slow voltage-dependent changes in channel open-state probability underlie hysteresis of NMDA responses in Mg2+-free solutions. Neuron. 1992;8:181–187. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P, Ascher P. Mechanosensitivity of NMDA receptors in cultured mouse central neurons. Neuron. 1994;13:645–655. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusch M, Neher E. Rates of diffusional exchange between small cells and a measuring patch pipette. Pflügers Archiv. 1988;411:204–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00582316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani A, Scarpa A. Regulation of cell magnesium. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1992;298:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90086-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C, Felts A, Westbrook GL. Synaptic NMDA receptor channels have a low open probability. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:2788–2795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02788.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman SM, Olney JW. Excitotoxicity and the NMDA receptor - still lethal after eight years. Trends in Neurosciences. 1995;18:57–58. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93869-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakimura K, Kutsuwada T, Ito I, Manabe T, Takayama C, Kushiya E, Yagi T, Aizawa S, Inoue Y, Sugiyama H, Mishina M. Reduced hippocampal LTP and spatial learning in mice lacking NMDA receptor ε1 subunit. Nature. 1995;373:151–155. doi: 10.1038/373151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands SB, Barish ME. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor currents in phaeochromocytoma (PC12) cells: dual mechanisms of rectification. Journal of Physiology. 1992;447:467–487. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sather W, Dieudonné S, Macdonald J, Ascher P. Activation and desensitization of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in nucleated outside-out patches from mouse neurons. Journal of Physiology. 1992;450:643–672. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sather W, Johnson JW, Henderson G, Ascher P. Glycine-insensitive desensitization of NMDA responses in cultured mouse embryonic neurons. Neuron. 1990;4:725–731. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90198-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolevsky AI, Koshelev SG, Khodorov BI. Probing of NMDA channels with fast blockers. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:10611–10626. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-24-10611.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout AK, Li-Smerin Y, Johnson JW, Reynolds IJ. Mechanisms of glutamate-stimulated Mg2+ influx and subsequent Mg2+ efflux in rat forebrain neurons in culture. Journal of Physiology. 1996;492:641–657. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollmuth LP, Kuner T, Sakmann B. Intracellular Mg2+ interacts with structural determinants of the narrow constriction contributed by the NR1-subunit in the NMDA receptor channel. Journal of Physiology. 1998;506:33–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.00033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z-G, Raouf R, Lu W-Y, Wang L-Y, Orser BA, Dudek EM, Browning MD, Macdonald JF. Regulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor function by constitutively active protein kinase C. Molecular Pharmacology. 1998;54:1055–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarei MM, Dani JA. Structural basis for explaining open-channel blockade of the NMDA receptor. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:1446–1454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01446.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Auerbach A. K+ occupancy of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor channel probed by Mg2+ block. Journal of General Physiology. 2001;117:287–297. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]