Abstract

AQP1-dependent CO2 transport has been suggested from the increased CO2 permeability in Xenopus oocytes expressing AQP1. Potential implications of this finding include AQP1-facilitated CO2 exchange in mammalian lung and HCO3−/CO2 transport in kidney proximal tubule. We reported previously that: (a) CO2 permeability in erythrocytes was not affected by AQP1 deletion, (b) CO2 permeability in liposomes was not affected by AQP1 reconstitution despite a 100-fold increased water permeability, and (c) CO2 blow-off by the lung in living mice was not impaired by AQP1 deletion. We extend these observations by direct measurement of CO2 permeabilities in lung and kidney. CO2 transport across the air-space-capillary barrier in isolated perfused lungs was measured from changes in air-space fluid pH in response to addition/removal of HCO3−/CO2 from the pulmonary artery perfusate. The pH was measured by pleural surface fluorescence of a pH indicator (BCECF-dextran) in the air-space fluid. Air-space fluid pH equilibrated rapidly (t1/2 ∼ 6 s) in response to addition/removal of HCO3−/CO2. However, the kinetics of pH change was not different in lungs of mice lacking AQP1, AQP5 or AQP1/AQP5 together, despite an up to 30-fold reduction in water permeability. CO2 transport across BCECF-loaded apical membrane vesicles from kidney proximal tubule was measured from the kinetics of intravesicular acidification in response to rapid mixing with a HCO3−/CO2 solution. Vesicles rapidly acidified (t1/2 ∼ 10 ms) in response to HCO3−/CO2 addition. However the acidification rate was not different in kidney vesicles from AQP1-null mice despite a 20-fold reduction in water permeability. The results provide direct evidence against physiologically significant transport of CO2 by AQP1 in mammalian lung and kidney.

Facilitated transport of CO2 by aquaporin-1 (AQP1) water channels has been suggested from comparative measurements on control and AQP1-expressing Xenopus oocytes. Nakhoul et al. (1998) reported a 30-40 % increased rate of cytoplasmic acidification after CO2 exposure in AQP1-expressing oocytes that were microinjected with carbonic anhydrase and impaled with pH-sensitive microelectrodes. Further work from the same group (Cooper & Boron, 1998) showed inhibition of CO2 transport by p-chloromercuriphenylsulfonic acid (pCMBS) in oocytes expressing wild-type AQP1 but lesser inhibition in oocytes expressing an AQP1 mutant lacking the cysteine known to be involved in water transport inhibition. The facilitated transport of CO2 by a membrane protein was a surprising observation given the very high CO2 permeability of biological membranes and consequent unstirred layer effects that are predicted to preclude an increase in apparent membrane CO2 permeability even if intrinsic membrane CO2 permeability could increase. Nevertheless, the potential consequences of AQP1-mediated CO2 permeability in mammalian physiology include AQP1-dependent CO2 exchange in erythrocytes and lung, and possibly AQP1-dependent HCO3− absorption by kidney proximal tubule. AQP1 is strongly expressed in cell plasma membranes in erythrocytes, alveolar capillary endothelia and kidney proximal tubule epithelia, sites where it has been shown in knockout mice to constitute the major pathway for osmotically driven water transport (Ma et al. 1998; Schnermann et al. 1998; Bai et al. 1999; Chou et al. 1999).

We recently investigated the possibility of AQP1-mediated CO2 transport by comparison of CO2 permeabilities in erythrocytes of wild-type vs. AQP1 null mice, and in liposomes vs. AQP1-reconstituted proteoliposomes (Yang et al. 2000). Apparent CO2 permeability was not impaired in erythrocytes lacking AQP1 despite a 7-fold reduced water permeability, nor was apparent CO2 permeability increased in proteoliposomes despite a > 100-fold increased water permeability. A previous report of HgCl2 inhibition of apparent CO2 permeability in AQP1-containing proteoliposomes (Prasad et al. 1998) was confirmed, but the reduced CO2 permeability was attributed to HgCl2 inhibition of carbonic anhydrase (added to the liposome lumen) rather than to inhibition of AQP1. We also tested whether AQP1 deletion in mice affected the physiological exchange of CO2 across the air-space-blood interface in lung. AQP1 deletion in mice did not affect the partial pressure of CO2 in blood, nor the kinetics of CO2 blow-off in anaesthetized, ventilated mice subject to an acute reduction in inspired CO2 content from 5 % to 0 % (Yang et al. 2000). In those studies the mice were not stressed, so that CO2 transport across the air-space-capillary barrier may have been limited by flow rather than diffusion and thus relatively insensitive to changes in the intrinsic CO2 permeability of alveolar capillaries. We did not measure CO2 or HCO3− transport in perfused kidney proximal tubules from AQP1-null mice because unstirred layers would preclude meaningful measurement of CO2 transport, and compensatory changes in transporter expression would preclude meaningful comparison of HCO3− transport in wild-type vs. AQP1-null mice.

This paper is part of a special issue of The Journal of Physiology containing reviews and commentaries written in conjunction with a Journal of Physiology-sponsored synthesium entitled ‘Water Transport Controversies’ that was held at the 2001 IUPS meeting in Christchurch, New Zealand. In addition to providing a commentary on the work of Professor Walter Boron and colleagues published in this issue (see Discussion), we report new data on CO2 permeability in lung and kidney of wild-type vs. AQP1 null mice. Diffusion-limited CO2 permeability was measured in isolated, rapidly perfused lungs utilizing a pleural surface fluorescence method in which changes in air-space fluid pH were followed in response to addition of HCO3−/ CO2 to the pulmonary artery perfusate. CO2 permeability of the proximal tubule cell luminal membrane was measured by a stopped-flow fluorescence method in isolated membrane vesicles. The new results extend our previous observations, and provide further evidence against physiologically important transport of CO2 by AQP1.

METHODS

Transgenic mice

Transgenic knockout mice deficient in AQP1 or AQP5 in a CD1 genetic background were generated by targeted gene disruption (Ma et al. 1998, 1999). AQP1-AQP5 double knockout mice were generated by serial breeding of the single knockout mice (Ma et al. 2000). All animal procedures were approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Animal Research.

Isolated lung perfusion

Mice were killed with intraperitoneal pentobarbital (150 mg kg−1). The trachea was cannulated with polyethylene PE-90 tubing, and the pulmonary artery with PE-20 tubing. The left atrium was transected to permit fluid exit. The pulmonary artery was gravity perfused at constant pressure (25-30 cmH2O) at room temperature. More than 90 % of lung perfusions were successful. The time between death and perfusion was generally < 7 min. The air-space was filled with 0.5 ml of a buffered isosmolar saline solution containing fluorescent indicators (see below).

Pleural surface fluorescence measurements

Air-space fluid fluorescence was measured by a pleural surface fluorescence method (Carter et al. 1996). The heart and lungs were positioned in a perfusion chamber for observation by epifluorescence microscopy. 2′,7′-Bis(carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF)-dextran (0.2 mg ml−1) was added to the air-space fluid as pH indicator or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran (70 kDa, 0.5 mg ml−1) as a volume marker. The fluorescence from a 3-5 mm diameter spot on the lung pleural surface was monitored continuously with an inverted epifluorescence microscope using a × 10 air objective and filter set consisting of 490 ± 10 nm excitation filter, 510 nm dichroic mirror, and > 515 nm cut-on filter. Signals were detected by a photomultiplier, amplified, digitized and recorded at a rate of 1 Hz. Rates of airway fluid pH change were determined from the time course of BCECF-dextran fluorescence in response to CO2/HCO3− gradients using an in vitro fluorescence vs. pH calibration. Osmotic water permeability (Pf) was computed from the time course of FITC-dextran fluorescence in response to osmotic gradients as described previously (Carter et al. 1996).

Measurement of air-space-capillary CO2 and osmotic water permeabilities

CO2 transport between the air-space and capillary compartments was determined from the time course of pleural surface fluorescence in response to exchange of CO2/HCO3−-free and CO2/HCO3−-containing perfusates. The air-space fluid contained 133 mm NaCl, 3 mm KCl, 0.68 mm CaCl2, 0.49 mm MgCl2, 1.5-25 mm sodium phosphate, and 1 % bovine serum albumin (pH 7.4, 300 mosmol kg−1). The air-space instillate also contained 0.5-2.5 mg ml−1 carbonic anhydrase (CA) to promote rapid CO2/HCO3− equilibration. The CO2/HCO3−-containing perfusate contained 25 mm NaHCO3 instead of NaCl and was bubbled with 5 % CO2. Osmotically driven water transport between the air-space and capillary compartment was measured as described previously (Bai et al. 1999; Song et al. 2000). The air-space fluid contained Hepes-buffered Ringer solution: 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 1.25 mm MgSO4, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 5.5 mm glucose, 12 mm Hepes, 1 % bovine serum albumin; pH 7.4, 300 mosmol kg−1. The perfusate was switched between osmolalities of 300 and 500 mosmol kg−1 (sucrose added).

Isolation and water permeability of proximal tubule apical membrane vesicles from mouse kidney

Sealed apical membrane vesicles from kidney proximal tubule were isolated by a magnesium aggregation procedure (Booth & Kenny, 1974; Ma et al. 1998). Osmotic water permeability in apical membrane vesicles was measured by stopped-flow light scattering as described previously (Ma et al. 1998).

CO2 permeability in apical membrane vesicles

Stopped-flow measurements were carried out on a Hi-Tech Sf-51 stopped-flow apparatus with dead time ∼1.2 ms. Vesicles were labelled with the acetoxymethyl ester of BCECF (BCECF AM, Molecular Probes) by incubation with 20 μM BCECF AM in PBS at 22 °C for 15 min. External dye was removed by four washes (12 000 g, 5 min). BCECF-labelled apical membrane vesicles were suspended at 5 mg protein ml−1 in 110 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 25 mm Hepes (bubbled for 30 min in N2) and mixed in the stopped-flow apparatus with an equal volume of 60 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 50 mm NaHCO3, 25 mm Hepes titrated to give specified pH after mixing with an equal volume of the vesicle suspension. Solutions were incubated at least 2 h in a sealed flask to insure CO2/HCO3− equilibration, and solution pH was checked before stopped-flow measurements. BCECF fluorescence was excited using a 485 ± 10 nm interference filter and detected using a > 515 nm cut-on filter. In some experiments, acetazolamide (0.1 mm) was added to the vesicle suspension. The apparent CO2 permeability coefficient (PCO2, cm s−1) was estimated as described previously (Yang et al. 2000) from an exponential time constant (τ) fitted to the fluorescence time course:

where S/V is vesicle surface-to-volume ratio (2.5 × 105 cm−1), pKa is 6.1, and pHf is final intravesicular pH determined from the drop in BCECF fluorescence.

RESULTS

CO2 permeability of the lung alveolar-capillary barrier

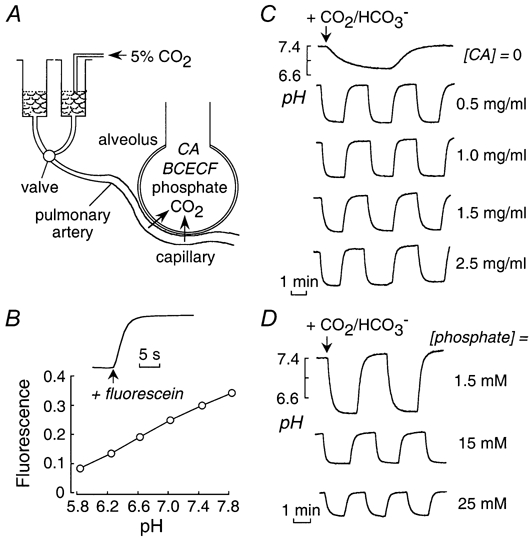

Figure 1A shows a schematic of the pleural surface method used to measure lung CO2 permeability. The air-space was filled with CO2/HCO3−-free fluid containing carbonic anhydrase to ensure rapid HCO3−/CO2/pH equilibration, and BCECF-dextran to give a pH-dependent fluorescence signal that was detected at the lung surface. Rapid exchange of the pulmonary artery perfusate from a CO2/HCO3−-free to a CO2/HCO3−-containing solution resulted in CO2 influx, producing a drop in pH and a decrease in BCECF fluorescence. The pH increased reversibly after return to a CO2/HCO3−-free solution. Figure 1B (inset) shows the perfusate exchange time in these experiments as determined from the kinetics of pleural surface fluorescence following the exchange of a non-fluorescent to fluorescent perfusate. The half-equilibration time (t1/2) was 1.3 s. Figure 1B shows that BCECF-dextran fluorescence is sensitive to pH in the range appropriate for the experiments here. By stopped-flow analysis, BCECF-dextran fluorescence responded in < 1 ms to pH changes in the pH range 6-8 (data not shown). These experiments demonstrate the suitability of the pleural surface fluorescence method to detect rapid air-space-capillary CO2 exchange.

Figure 1. Air space-capillary CO2 transport in mouse lung measured by a pleural surface fluorescence method.

A, schematic showing an isolated perfused mouse lung. The air-space fluid contains carbonic anhydrase and the fluorescent pH indicator BCECF-dextran. The pulmonary artery perfusate was exchanged between isosmolar CO2/HCO3−-free and CO2/HCO3−-containing solutions. CO2/HCO3− addition results in acidification of air-space fluid and a decrease in pleural surface BCECF-dextran fluorescence. B, relationship between BCECF fluorescence and pH. Inset, perfusate exchange rate. Time course of pleural surface fluorescence in response to exchange between non-fluorescent and fluorescent (containing FITC-dextran) perfusates. Perfusate flow rate was 3-5 ml min−1, as in subsequent CO2 transport measurements. C, time course of air-space fluid pH (computed from pleural surface fluorescence) in response to exchange between CO2/HCO3−-free and CO2/HCO3−-containing perfusates. Air-space fluid contained carbonic anhydrase (CA) at indicated concentrations. D, same as in C (with 1 mg ml−1 CA) in which the air-space instillate contained indicated amounts of phosphate buffer.

Figure 1C shows representative time courses of air-space fluid pH in response to exchange between CO2/HCO3−-free and CO2/HCO3−-containing pulmonary artery perfusates. The pH equilibration was slow in the absence of carbonic anhydrase in the air-space fluid (top curve). The pH equilibration was rapid (t1/2 ∼ 5.6 s) and reversible in the presence of carbonic anhydrase. The equilibration time was not sensitive to carbonic anhydrase concentration in range 0.5-2.5 mg ml−1, as predicted from the millisecond kinetics of CO2/HCO3− equilibration at these concentrations reported in previous stopped-flow measurements (Yang et al. 2000). The magnitude of the pH drop was sensitive to air-space fluid buffer capacity, increasing from 0.47 to 1.3 pH units for air-space solutions containing 25 and 1.5 mm phosphate, respectively (Fig. 1D). The non-linear dependence of the drop in pH on instillate buffer capacity indicates that the alveolar lumen contains endogenous buffers such as cell surface proteins.

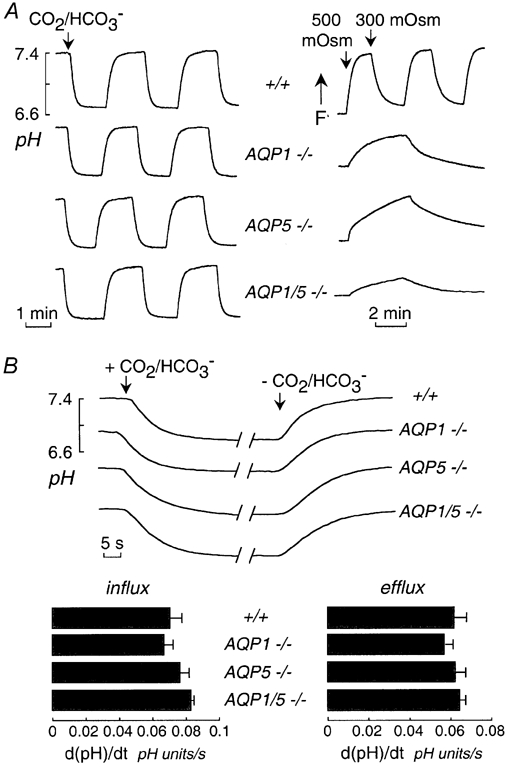

Measurements of air-space-capillary CO2 exchange were done in wild-type mice, and mice lacking AQP1 and AQP5, individually and together. Representative fluorescence time course data in Fig. 2A (left) show no apparent affect of aquaporin deletion. Measurement of air-space-capillary osmotically induced water permeability showed marked reduction in water permeability in the aquaporin-null mice (Fig. 2A, right). Water permeability was 10-fold reduced by deletion of AQP1 or AQP5 separately, and was further reduced ∼3 fold by their deletion together. Figure 2B (top) shows the direct comparison on an expanded time scale of changes of air-space fluid pH following CO2/HCO3− addition and removal. Figure 2B (bottom) summarizes the rates of CO2 influx and efflux for lungs from a series of mice. There was no significant effect of aquaporin deletion on air-space-capillary CO2 transport.

Figure 2. Influence of aquaporin deletion on air-space-capillary CO2 and osmotic water permeabilities.

A, left, CO2 permeability in lungs from mice of indicated genotype. Time course of air-space fluid pH in response to exchange between CO2/HCO3−-free and CO2/HCO3−-containing perfusates measured as in Fig. 1C. The air-space instillate contained 1 mg ml−1 CA and the perfusate contained 0 or 25 mm HCO3−. Right, osmotic water permeability. Time course of air-space fluid osmolality (measured by FITC-dextran fluorescence) in response to exchange between perfusates of osmolality 300 and 500 mosmol kg−1. B, top, representative time course data as in A (left) shown on an expanded time scale. Bottom, summary of rates of CO2 transport into and out of the air-space fluid. Data are shown as mean and s.e.m. for n = 3.5 lungs per group. Differences not significant.

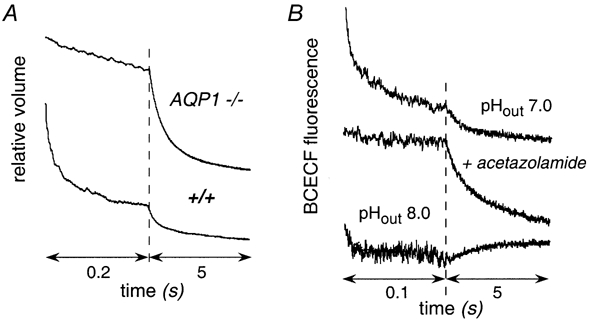

CO2 permeability of proximal tubule vesicles

Figure 3A shows osmotic water permeability in suspended proximal tubule vesicles measured by stopped-flow light scattering. Osmotic water permeability coefficients (Pf) were 0.039 ± 0.002 cm s−1 (wild-type) and 0.0020 ± 0.0002 cm s−1 (AQP1 null), indicating that AQP1 provides the major route for water transport in these membranes. The low Pf after AQP1 deletion suggests water movement across the lipid bilayer.

Figure 3. Osmotic water permeability and CO2 permeability in apical membrane vesicles from mouse kidney proximal tubule.

A, vesicles were subjected to a 250 mm inwardly directed sucrose gradient at 10 °C. Data are plotted using two contiguous times scales to show the complete osmotic equilibration. B, vesicles were loaded with the fluorescent pH indicator BCECF and suspended in an isosmolar buffer at pH 7.4 (not containing CO2/HCO3−, see Methods). The suspension was mixed in a stopped-flow apparatus with appropriate buffers to give 25 mm CO2/HCO3− at pH 7.0 or 8.0. Where indicated, vesicles were incubated with acetazolamide prior to the assay. Curves have been displaced arbitrarily in the y-direction for clarity.

CO2 transport was measured from the kinetics of intravesicular acidification following rapid mixture of vesicles suspended in a CO2/HCO3−-free buffer with an isosmolar buffer containing CO2/HCO3−. Intravesicular CO2/HCO3−/pH equilibration is facilitated by the endogeneous membrane-associated carbonic anhydrase (type IV) present on proximal tubule cell membranes (Maren et al. 1993; Brion et al. 1997). The vesicles were loaded with the fluorescent pH indicator BCECF by incubation with BCECF AM followed by extensive washing. The intravesicular de-esterification of BCECF AM in these vesicles is thought to arise in part from carbonic anhydrase activity, so that vesicles containing higher amounts of carbonic anhydrase are preferentially labelled. Figure 3B shows the time course of intravesicular BCECF fluorescence following exposure of proximal tubule vesicles (from wild-type mice) to a CO2-equilibrated solution containing 25 mm HCO3− at indicated pHout. There was a biphasic time course of decreasing fluorescence, with 75-80 % of the signal dropping very rapidly (t1/2 ∼ 10 ms) and the remaining signal dropping over ∼300 ms. The rapid phase of decreasing fluorescence probably corresponds to CO2 transport in a population of proximal tubule apical membrane vesicles containing relatively large amounts of carbonic anhydrase; the slower signal component may correspond to contaminating vesicles or vesicles from regions of the proximal tubule containing less carbonic anhydrase. This interpretation is supported by the slowed acidification after incubation of vesicles with the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor acetazolamide (Fig. 3B, second curve). As expected, the magnitude of the prompt intracellular acidification was decreased with increasing extracellular pH because of the decrease in CO2/HCO3− ratio (Fig. 3B, third curve).

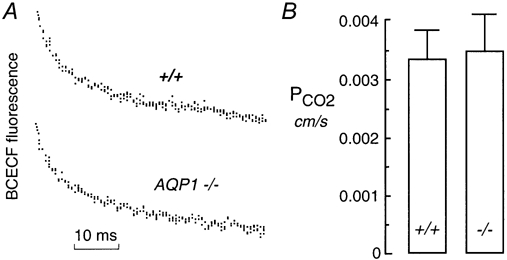

CO2 permeability was compared in proximal tubule vesicles isolated from kidneys of three wild-type and three AQP1-null mice. Representative stopped-flow data are given in Fig. 4A, showing similar kinetics of acidification in vesicles from wild-type and AQP1-null mice. Figure 4B summarizes apparent CO2 permeability coefficients (PCO2) computed from acidification rates, final intravesicular pH, and vesicle geometry (see Methods). PCO2 was not significant affected by AQP1 deletion: 0.0034 ± 0.0005 cm s−1 (wild-type) and 0.0035 ± 0.0006 cm s−1 (AQP1 null).

Figure 4. Influence of AQP1 deletion on CO2 permeability in apical membrane vesicles from proximal tubule.

A, vesicles were subjected to a 25 mm CO2/HCO3− gradient at a final outside pH of 7.0 as in Fig. 3B. B, averaged PCO2 computed from experiments as in A. Data are means and s.e.m.

DISCUSSION

The experiments here address whether transport of CO2 by AQP1 is physiologically important in lung and kidney. Measurements in the isolated perfused lung under diffusion-limited conditions extend previous data in living ventilated mice showing no effect of AQP1 deletion on CO2 transport across the air-space-capillary barrier. The measurements in kidney proximal tubule vesicles indicate that CO2 transport across the proximal tubule apical membrane is rapid and not affected by AQP1 deletion. Additional comments follow, after which general issues with regard to aquaporin-mediated CO2 transport are discussed.

The exchange of CO2 between the air-space and erythrocytes in alveolar capillaries involves CO2 movement across the alveolar epithelium and endothelium, and the erythrocyte membrane, as well as CO2 diffusion through the lung interstitium and serum. CO2 transport across the erythrocyte membrane is not rate limiting in air-space-erythrocyte CO2 exchange since CO2 equilibration in erythrocytes occurs within a few milliseconds (Yang et al. 2000) and is facilitated by anion exchange of HCO3− catalysed by carbonic anhydrase. The question addressed here is whether aquaporin-dependent CO2 transport across the alveolar barriers facilitates air-space-capillary CO2 equilibration. CO2 transport into and out of the air-space was measured by a kinetic approach, from the time course of air-space fluid pH in response to changes in the CO2/HCO3− content of fluid perfused rapidly through the pulmonary artery. Changes in air-space CO2 content were followed from the fluorescence of a pH indicator in the air-space fluid using carbonic anhydrase to ensure rapid HCO3−/CO2 and thus pH equilibration. Stopped-flow measurements showed previously that HCO3−/CO2/pH equilibration occurs in < 1 ms, a time much faster than that of alveolar-capillary CO2 exchange measured here. The rapid pulmonary artery perfusion and the measurement of pH in a small volume of air-space fluid by the pleural surface fluorescence method minimized effects of uneven capillary perfusion.

We found that CO2 exchange across the lung alveolar epithelial and endothelial barriers was rapid and not affected by deletion of AQP1 and/or AQP5, whereas osmotically induced water permeability was reduced by up to 30-fold. The time for pH equilibration was much slower than the time for perfusate exchange as measured by addition of a fluorescent marker to one of the perfusates. Aquaporin-mediated CO2 transport thus does not contribute to CO2 equilibration across the air-space-capillary barrier.

CO2 transport across the AQP1-containing apical membrane of kidney proximal tubule was measured from the rate of acidification in apical membrane vesicles following rapid exposure to CO2/HCO3− in a stopped-flow apparatus. Measurement of CO2 transport in small suspended vesicles is advantageous to measurements in intact proximal tubule because more rapid mixing is possible, and because the small size and single barrier structure of vesicles minimizes unstirred layer effects. We found rapid CO2 transport across the proximal tubule apical membrane that was not affected by AQP1 deletion. It is thus unlikely that CO2 transport by AQP1 could augment proximal tubule HCO3− absorption. Indeed, the data of Vallon et al. (2000), in which end-proximal tubule micropuncture samples were analysed for tubular fluid osmolarity and chloride concentration, provided evidence against significant accumulation of HCO3− at the end proximal tubule of AQP1-null mice. AQP1 deficiency in mice generates marked luminal hypotonicity in proximal tubules, indicating that near-isosmolar fluid absorption requires functional AQP1. However, ion/HCO3− transport data in AQP1-null mice should be viewed cautiously because of compensatory changes in proximal tubule transporter expression. When available, potent non-toxic AQP1 inhibitors will be useful in defining the role of AQP1 in complex systems involving osmotic and electrochemical gradients produced by multiple interacting transporting systems.

A concern in the measurement of CO2 permeability across highly CO2-permeable biological membranes is unstirred layer effects. Diffusion of CO2 in unstirred aqueous solutions adjacent to membranes is generally substantially slower than CO2 transport across the membrane itself. However, we note that unstirred layer effects in experimental models of CO2 transport are relevant in vivo, so that augmentation of CO2 transport by an aquaporin or other protein would be possible only when intrinsic membrane CO2 permeability is exceptionally low, or by some unusual mechanism involving spatially organized CO2 generation and channelling.

Unstirred layer effects are predicted to be greatest for large and complex cellular systems and when CO2 diffusion is slowed by high cytoplasmic viscosity as expected in Xenopus oocytes. With respect to CO2 transport, intrinsic membrane permeabilities have been estimated by extrapolation of CO2 transport rates at high pH in the presence of carbonic anhydrase where CO2 is rapidly created/dissipated near membranes by high concentrations of HCO3− (Suchdeo & Schultz, 1973; Geers & Gros, 2000). As summarized in Table 1, the true CO2 permeability (PCO2) across planar lipid bilayer is very high (≈0.35 cm s−1, Gutknecht et al. 1977). A cleaver approach to estimate true CO2 permeability in erythrocytes by establishing a quasi-steady-state CO2 profile (Forster et al. 1998) also indicated a very high membrane PCO2 of ∼1 cm s−1. More conventional CO2 mixing approaches, which are relevant in vivo, give substantially lower PCO2 values of < 0.01 cm s−1 as summarized in Table 1 for erythrocytes, liposomes, kidney vesicles and Xenopus oocytes. It is thus likely that CO2 transport in each of these cases is unstirred-layer limited and so not sensitive to intrinsic membrane CO2 permeability. Thus, as discussed previously (Yang et al. 2000), we can only report an upper limit to the quantity of CO2 transported by individual AQP1 monomers. With regard to mammalian physiology, direct evidence in erythrocytes, lung and kidney argues strongly against physiologically important transport of CO2 by AQP1.

Table 1.

CO2 permeabilities (PCO2) of lipid bilayers and biological membranes

| System | Measurement method | PCO2(cm s−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planar bilayer | pH measurements | 0.35 | Gutknecht et al. 1977 |

| Erythrocyte | Mass spectrometry | ∼1 | Forster et al. 1998 |

| Luminal pH kinetics | 0.01 | Yang et al. 2000 | |

| Liposome | Luminal pH kinetics | 0.001 | Yang et al. 2000 |

| Proximal tubule vesicle | Luminal pH kinetics | 0.0035 | This paper |

| Corneal cell cultures | Cytoplasmic pH (BCECF) | 0.0036 | Sun et al. 2001 |

| Xenopus oocyte | pH microelectodes | 0.006 | Nakhoul et al. 1998 |

In conclusion, the transport of small gases by aquaporins is an interesting hypothesis, though from the experiments reported here, and based on general principles, physiologically significant transport of CO2 by AQP1 is unlikely. We showed previously that NH3 transport in erythrocytes, which is relatively slow and thus not unstirred-layer limited, is not affected by AQP1 deletion (Yang et al. 2000). Aquaporin-mediated transport of other small gases (O2, CO, NO) may warrant investigation; however, the high intrinsic membrane permeabilities for these gases makes aquaporin-facilitated transport unlikely. Finally, transport measurements of CO2, NH3 and other small gases by the aquaglyceroporins (AQP3, AQP7 and AQP9) may be interesting. These proteins are able to transport glycerol and some small solutes along with water, and so may contain a relatively wide, non-selective pore.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants DK35124, HL59198, HL51856, HL60288 and DK43840 from the National Institutes of Health and a grant from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Bai C, Fukuda N, Song Y, Ma T, Matthay MA, Verkman AS. Lung fluid transport in aquaporin-1 and aquaporin-4 knockout mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;103:555–561. doi: 10.1172/JCI4138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth AG, Kenny AJ. A rapid method for the preparation of microvilli from rabbit kidney. Biochemical Journal. 1974;142:575–581. doi: 10.1042/bj1420575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brion LP, Cammer W, Satlin LM, Suarez C, Zavilowitz BJ, Schuster VL. Expression of carbonic anhydrase IV in carbonic anhydrase II-deficient mice. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:F234–245. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.2.F234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter EP, Matthay MA, Farinas J, Verkman AS. Transalveolar osmotic and diffusional water permeability in intact mouse lung measured by a novel surface fluorescence method. Journal of General Physiology. 1996;108:133–142. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.3.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou CL, Knepper MA, Hoek AN, Brown D, Yang B, Ma T, Verkman AS. Reduced water permeability and altered ultrastructure in thin descending limb of Henle in aquaporin-1 null mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;103:491–496. doi: 10.1172/JCI5704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper GJ, Boron WF. Effect of PCMBS on CO2 permeability of Xenopus oocytes expressing aquaporin 1 or its C189S mutant. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:C1481–1486. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.6.C1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster RE, Gros G, Lin L, Ono Y, Wunder M. The effect of 4,4′-diisothiocyanato-stilbene-2,2′-disulfonate on CO2 permeability of the red blood cell membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:15815–15820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geers C, Gros G. Carbon dioxide transport and carbonic anhydrase in blood and muscle. Physiological Reviews. 2000;80:681–715. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutknecht J, Bisson MA, Tosteson FC. Diffusion of carbon dioxide through lipid bilayer membranes: effects of carbonic anhydrase, bicarbonate, and unstirred layers. Journal of General Physiology. 1977;69:779–794. doi: 10.1085/jgp.69.6.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Fukuda N, Song Y, Matthay MA, Verkman AS. Lung fluid transport in aquaporin-5 knockout mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;105:93–100. doi: 10.1172/JCI8258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Song Y, Gillespie A, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Verkman AS. Defective secretion of saliva in transgenic mice lacking aquaporin-5 water channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:20071–20074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Yang B, Gillespie A, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Verkman AS. Severely impaired urinary concentrating ability in transgenic mice lacking aquaporin-1 water channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:4296–4299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren TH, Wynns GC, Wistrand PJ. Chemical properties of carbonic anhydrase IV, the membrane-bound enzyme. Molecular Pharmacology. 1993;44:901–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakhoul NL, Davis BA, Romero MF, Boron WF. Effect of expressing the water channel aquaporin-1 on the CO2 permeability of Xenopus oocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:C543–548. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.2.C543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad GV, Coury LA, Finn F, Zeidel ML. Reconstituted aquaporin 1 water channels transport CO2 across membranes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:33123–33126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnermann J, Chou CL, Ma T, Traynor T, Knepper MA, Verkman AS. Defective proximal tubular fluid reabsorption in transgenic aquaporin-1 null mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:9660–9664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Ma T, Matthay MA, Verkman AS. Role of aquaporin-4 in airspace-to-capillary water permeability in intact mouse lung measured by a novel gravimetric method. Journal of General Physiology. 2000;115:17–27. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchdeo S, Schultz JS. Effect of carbonic anhydrase on the facilitated diffusion of CO2 through bicarbonate solutions. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 1973;37:969–974. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5089-7_39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XC, Xie Q, Stamer WD, Bonanno JA. Effect of AQP1 expression level on CO2 permeability in bovine corneal endothelium. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2001;42:417–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallon V, Verkman AS, Schnermann J. Luminal hypotonicity in proximal tubules of aquaporin-1-knockout mice. American Journal of Physiology – Renal Physiology. 2000;278:F1030–1033. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.6.F1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Fukuda N, van Hoek A, Matthay MA, Ma T, Verkman AS. Carbon dioxide permeability of aquaporin-1 measured in erythrocytes and lung of aquaporin-1 null mice and in reconstituted proteoliposomes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:2686–2692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]