Abstract

Paired recordings between CA3 interconnected pyramidal neurons were used to study the properties of short-term depression occurring in these synapses under different frequencies of presynaptic firing (n = 22). In stationary conditions (0.05–0.067 Hz) pairs of presynaptic action potentials (50 ms apart) evoked EPSCs whose amplitude fluctuated from trial to trial with occasional response failures. In 15/20 cells, paired-pulse ratio (PPR) was characterized by facilitation (PPF) while in the remaining five by depression (PPD). Increasing stimulation frequency from 0.05–0.067 Hz to 0.1–1 Hz induced low frequency depression (LFD) of EPSC amplitude with a gradual increase in the failure rate. Overall, 9/12 cells at 1 Hz became almost ‘silent’. In six cells in which the firing rate was sequentially shifted from 0.05 to 0.1 and 1 Hz, changes in synaptic efficacy were so strong that PPR shifted from PPF to PPD. The time course of depression of EPSC1 could be fitted with single exponentials with time constants of 98 and 36 s at 0.1 and 1 Hz, respectively. In line with the inversion of PPR at 1 Hz, the time course of depression of EPSC2 was faster than EPSC1 (7 s). Recovery from depression could be obtained by lowering the frequency of stimulation to 0.025 Hz. These results could be explained by a model that takes into account two distinct release processes, one dependent on the residual calcium and the other on the size of the readily releasable pool of vesicles.

Short-term forms of synaptic plasticity are crucial for regulating the temporal code and information processing between neurons in a network (Tsodyks & Markram, 1997). These vary from synapse to synapse and in the same synapse according to its previous history (Markram & Tsodkys, 1996; Debanne et al. 1996; Canepari & Cherubini, 1998; Markram et al. 1998). One common form of short-term plasticity lasting from seconds to minutes is depression upon repeated use (Thomson & Deuchars, 1994; Nelson & Turrigiano, 1998). This may provide a dynamic gain control over a variety of presynaptic afferent firing action potentials at different rates (Markram & Tsodyks, 1996; Abbott et al. 1997; O'Donovan & Rinzel, 1997). This form of plasticity may reflect mainly presynaptic depletion of a readily releasable pool of vesicles (Rosenmund & Stevens, 1996; Wang & Kaczmarek, 1998; Oleskevich et al. 2000; Meyer et al. 2001). However, other mechanisms, such as presynaptic calcium channel inactivation (Gingrich & Byrne, 1985), negative feedback through inhibitory autoreceptors (Forsythe & Clements, 1990) or receptor desensitization (Otis et al. 1996; Neher & Sakaba, 2001) cannot be ruled out.

In most cases, synaptic depression should be dependent on previous release (Debanne et al. 1996) in such a way that, in a paired-pulse protocol, the ratio between the mean amplitudes of the second EPSC over the first EPSC (paried-pulse ratio, PPR) is inversely related to the initial release probability (Dobrunz & Stevens, 1997). In general, the smaller is the probability of release to the first pulse, the more facilitated is the response to the second pulse. This phenomenon, known as paired-pulse facilitation (PPF), is accounted for by the residual calcium hypothesis, according to which the small fraction of calcium entering the terminal during the first spike increases the probability of transmitter release to a second action potential (Zucker, 1989). It follows that if repetitive stimulation of presynaptic neurons causes a reduction in the release probability and, therefore, in the amplitude of the first EPSC (Thomson et al. 1993), it should induce a further facilitation of the second EPSC, leading to an increase in PPR. The present experiments were undertaken to see whether the relation between PPR and probability of release was still maintained during use-dependent depression.

In the hippocampus, synaptic depression has been studied mainly with minimal stimulation of afferent inputs (Voronin, 1993; Larkman et al. 1997; Gasparini et al. 2000). With this method it is impossible to ascertain that the same presynaptic axon is activated trial after trial as different axons are likely to be stimulated. Moreover failures of presynaptic release cannot be unambiguously distinguished from failures of the stimulus to trigger an action potential in the presynaptic fibre. To overcome these problems we used whole-cell recordings from pairs of interconnected CA3–CA3 pyramidal neurons in hippocampal slice cultures (Debanne et al. 1996; Pavlidis & Madison, 1999). We found that in the majority of neurons low frequency depression (LFD) was associated with a reduction in EPSC amplitude. The magnitude of LFD varied between pairs and depended on the rate of presynaptic firing. Unexpectedly PPR was reduced at higher presynaptic firing frequency (1 Hz) and, on average, PPF was converted into PPD suggesting that during LFD release probability results from the balance of at least two distinct processes, one depending on the residual calcium and the other on the number of available vesicles.

METHODS

Organotypic cultures

Hippocampi were removed from 4- to 7-day-old rats killed by decapitation and organotypic cultures were prepared following the method already described (Gähwiler, 1981). The procedure was performed in accordance with the regulations of the Italian Animal Welfare Act and was approved by the local authority veterinary service. Transverse 400 μm thick slices were cut with a tissue chopper and attached to coverslips in a film of reconstituted chicken plasma (Cocalico, Reamstown, PA, USA) clotted with thrombin (Sigma, Milan, Italy). The coverslips were transferred to plastic tubes containing 0.75 ml of medium. The tubes were placed in a roller drum (6 revolutions h−1) inside an incubator at 36 °C. The medium contained: basal medium (BME, Eagle, with Hanks' salts, without l-glutamine; Gibco, 100 ml), Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS; Gibco, 50 ml), horse serum (Gibco, 50 ml), l-glutamine (Gibco, 200 mm, 1 ml), 50 % d-glucose in sterile water for tissue culture (Gibco, 2 ml).

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings

After 10-14 days incubation, slices, which had flattened near-monolayer thickness, were transferred to a recording chamber fixed to the stage of an upright microscope. Cultured slices in the recording chamber were superfused at room temperature (22-24 °C) with a bath solution containing (mm): 150 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 10 glucose (adjusted to pH 7.3 with NaOH). Electrophysiological experiments were performed on CA3 pyramidal neurons using the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique in current (presynaptic cell) and voltage clamp mode (postsynaptic cell). Patch electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (Hingenberg, Malsfeld, D). They had a resistance of 3-6 MΩ when filled with an intracellular solution containing (mm): 135 KMeSO4, 10 KCl, 10 Hepes, 1 MgCl2, 2 Na2ATP, 0.4 Na2GTP for the presynaptic cell and 135 CsMeSO4, 10 CsCl, 10 Hepes, 5 QX 314, 0.5 EGTA, 2 MgATP, 0.3 NaGTP for the postsynaptic cell; pH was adjusted to 7.3 with KOH and CsOH, respectively. Pairs of presynaptic action potentials (50 ms interval) were evoked at resting membrane potential (−58.1 ± 0.73 mV) by short (5 ms) depolarizing current pulses at different frequency (from 0.025 to 1 Hz). AMPA-mediated EPSCs were recorded at a holding potential of −60 mV. A liquid junction potential of 9 mV was not corrected. In some experiments (n = 4) the NMDA receptor antagonist 2-amino-5-phosphopentanoic acid (AP5, obtained from Tocris Cookson Ltd, Bristol, UK) was added to the perfusion solution to block NMDA receptors.

Data were sampled at a rate of 20 kHz and filtered with a cut off frequency of 1 kHz. Series resistance compensation was used only for the presynaptic cell.

Data acquisition and analysis

EPSCs were stored on a magnetic tape and transferred to a computer after digitization with an A/D converter (Digidata 1200). Data acquisition was done using pCLAMP (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). EPSCs were analysed with AxoGraph 4.6 (Axon Instruments), which uses a detection algorithm based on a sliding template. The onset of the EPSC was given by the intersection of a line through the 20 and 80 % of EPSC rise time with the baseline. The same program was used to fit the decay phase of the EPSCs with a monoexponential function. Failures (N0) were identified visually. In a set of experiments (n = 12), in order to control the adequacy of the visual selection, the fraction of responses with amplitude > 0 pA, corresponding to failures, was calculated. Since failures should be symmetrically distributed around zero, N0 was calculated by doubling this fraction (Nicholls & Wallace, 1978). A similarity and a high correlation between N0 estimated by the two methods were found (mean failure rates were 84.9 ± 4.5 and 81.5 ± 6.0 %, respectively, r = 0.95; P < 0.001).

For any given frequency, mean EPSC amplitude was obtained by averaging successes and failures.

The time course of synaptic depression and recovery could be fitted with a monoexponential function (using a Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm implemented in SigmaPlot 2001, Jandel, Germany). Data points were obtained by averaging for any given frequency EPSC amplitudes over four to eight consecutive trials and normalizing them to the first value in the train (I/I1st, in the case of depression) or to the mean EPSC amplitude obtained in control conditions (I/Icontrol, in the case of recovery from depression).

Values are given as means ± s.e.m. Significance of differences was assessed using Student's t test or the Wilcoxon signed rank test. The differences were considered significant when P was < 0.05.

RESULTS

Stable long-lasting (>30 min) whole-cell recordings were obtained from 22 CA3 pyramidal cell pairs. Interconnected neurons were identified as pyramidal cells both visually and on the basis of their firing properties, i.e. their ability to accommodate in response to long (800 ms) depolarizing current pulses. The identity of the connected cells as pyramidal neurons was confirmed in three experiments in which cell pairs were labelled with neurobiotin. In control conditions, pairs of presynaptic action potentials (50 ms apart), delivered at the frequency of 0.05–0.067 Hz, evoked two sequential EPSCs that fluctuated in amplitude from trials to trials with occasional response failures (Fig. 1). Paired-pulse modulation was quantified by calculating the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) as the ratio between the mean amplitude of the second and the first EPSC. In agreement with previous reports (Debanne et al. 1996; Pavlidis & Madison, 1999) a strong heterogeneity in PPR across different connections was observed. The majority of cells (15 of 20) exhibited PPF (1.4 ± 0.1, see Fig. 1), while the remaining five exhibited PPD (0.7 ± 0.1).

Figure 1. Low frequency depression induced in a synaptically connected pair of CA3 neurons by increasing the presynaptic firing frequency from 0.05 to 1 Hz.

A and B, ten postsynaptic responses (B) induced by pairs of depolarization-evoked action potentials (50 ms apart) in the presynaptic cell (A) are superimposed for each frequency. The resting potential of both neurons was −60 mV. C, all EPSCs evoked at a given frequency (including failures) are averaged. D, time course of EPSC amplitude to the first and second pulse for the same neuron shown in A-C.

Properties of low frequency depression

Increasing frequency of presynaptic firing from 0.05–0.067 to 0.1–1 Hz induced depression of postsynaptic responses (n = 14). The degree of synaptic depression was heterogeneous across different pairs but was clearly dependent on the testing frequency, being larger at higher frequencies. As shown in the example of Fig. 1, consecutive changes in presynaptic firing frequency from 0.05, to 0.1 and 1 Hz induced a gradual reduction in the number of successes, leading only to transmission failures. Overall, in 9 of 12 cells at the end of a 1 Hz low frequency train, synaptic transmission was almost completely abolished (Fig. 1D and Fig. 2C). In the remaining three cells 1 Hz stimulation induced a reduction of the mean amplitude of synaptic responses of 60 ± 10 and 70 ± 10 %, for EPSC1 and EPSC2, respectively, although only a few failures were observed. Successful transmission reappeared in all cells examined (n = 8) after switching to a lower frequency (0.025 Hz).

Figure 2. Short-term depression in a synapse with high release probability.

A, superimpositions of ten EPSC pairs evoked at different frequencies by presynaptic action potentials. B, all EPSCs evoked at a given frequency (including failures) are averaged (scale bar is the same for A and B). C, time course of EPSC amplitude to the first (filled circles) and second pulse (open circles) for the same neuron shown in A and B.

Interaction between paired-pulse modulation and low frequency depression

In the example of Fig. 1, increasing the stimulation frequency from 0.05 to 0.1 Hz produced a reduction in the amplitude of both EPSC1 and EPSC2. This was associated with an enhanced number of failures and a slight decrease in PPR. The figure shows also that a further increase of stimulation frequency to 1 Hz strongly depressed both responses. Unexpectedly EPSC2 became silent before EPSC1, leading to the conversion of PPF into PPD. Responses reappeared after setting the frequency of stimulation to 0.025 Hz (Fig. 1D and E). In this particular case EPSC1 recovered less than EPSC2 leading to a very strong PPF.

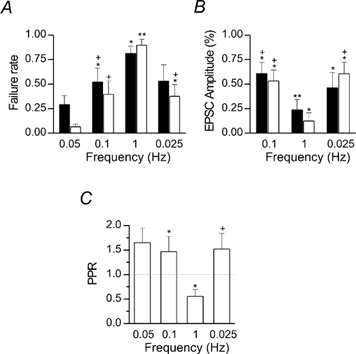

LFD was observed also in cases with initial high probability of release as in the example of Fig. 2, where only successes were recorded in control conditions (at 0.05 Hz). Increasing the stimulation frequency led to a decrease in the mean EPSCs amplitude and to the appearance of some transmission failures. Again, at 1 Hz, the responses were almost abolished with sporadic responses to EPSC2. A complete recovery of both EPSC1 and EPSC2 was obtained at 0.025 Hz (Fig. 2A-C). Similar depression and recovery were observed in an additional four neurons that were sequentially tested at 0.05, 0.1, 1 and 0.025 Hz. Mean values of failure rate, changes in EPSC amplitudes and PPR are shown in Fig. 3. While at 0.05 Hz the failure rate in response to the first spike was significantly higher than that to the second (filled and open columns of Fig. 3A, respectively, P < 0.05), at 0.1 Hz this difference was less pronounced. At 1 Hz, the failure rate of synaptic response to the second spike was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than that to the first one. A partial recovery was observed at 0.025 Hz (n = 4). The higher failure rate found at 0.025 Hz in comparison with that at 0.05 Hz reflects the slowness of the recovery process since, for any given frequency, we analysed responses occurring during the entire period of stimulation. This also accounts for the smaller mean EPSC amplitude measured at 0.025 Hz with respect to controls (Fig. 3B, see also Fig. 2B and C). In fact, the percentage of recovery obtained after the first 5 min was 70 ± 20 and 80 ± 20 %, for EPSC1 and EPSC2, respectively (n = 3). This rules out the possibility of long-term depression (Montgomery & Madison, 2002) or response run down. At 0.1 and 1 Hz, changes in failure rate were associated with a reduction in the mean EPSC amplitude (Fig. 3B). The greater reduction of EPSC2 in comparison with EPSC1 is in line with the frequency-dependent PPR changes shown in Fig. 3C. Similar results were found in an additional eight neurons in which use-dependent depression was investigated using different stimulation frequencies.

Figure 3. Summary data of changes in failures rate, amplitude and paired-pulse ratio of synaptic responses evoked at different frequencies.

A, failure rates to the first (filled columns) and second (open columns) pulse under different frequencies of stimulation (n = 5). B, mean EPSC amplitude plotted for three different frequencies as a percentage of control (six connected pairs). C, PPR calculated at different frequencies for the same six pairs of cells (0.025 Hz refers to 3 neurons). Reference marks (* and +) indicate significant differences from control or from 1 Hz values, respectively. Single reference marks indicate P < 0.05 and double reference marks P < 0.001.

Time course of low frequency depression

The amount of depression varied from cell to cell according to their previous history (i.e. to the duration and frequency of stimulation). In the graphs of Fig. 4, the time courses of depression and recovery are shown. While at 0.05 Hz, the mean EPSC amplitudes remained stable (Fig. 4A), LFD appeared at the presynaptic firing frequency of 0.1 Hz and strongly increased at 1 Hz (Fig. 4B and C). The time course of depression of EPSC1 could be fitted with a mono-exponential function having a time constant of 98 and 36 s at 0.1 and 1 Hz, respectively. Interestingly, the time course of depression of EPSC2 did not follow that of EPSC1. While at 0.1 Hz, depression of EPSC2 was slower than EPSC1 (time constants of 145 versus 98 s), at 1 Hz it was faster (7 versus 36 s). All synapses slowly recovered from depression during 0.025 Hz stimulation. The time course of recovery was well described by a single exponential function having a time constant of 594 and 603 s for EPSC1 and EPSC2, respectively (Fig. 4D). The slowness of this process may account for the incomplete (70 ± 20 %) recovery of EPSC1 after 5 min. In line with a presynaptic site of action, LFD did not modify EPSC kinetics (Fig. 4E). As shown in Fig. 4F, the decay time constants of single EPSCs evoked at different frequencies were not significantly different (P = 0.89). Moreover, taking advantage of the double recordings technique, possible modifications of the presynaptic action potential were investigated. In spite of a small reduction in spike amplitude (from 92 ± 9 to 86 ± 9 mV), no change in spike half-width value (from 1.7 ± 0.1 to 1.66 ± 0.07 ms) was observed between 0.05 and 1 Hz.

Figure 4. Time course of frequency depression and recovery.

A-D, time course of normalized mean EPSC amplitude evoked at different frequencies (n = 5-6 neurons for A-C and 3 for D, see methods for normalization). Filled and open circles refer to the first and second EPSC, respectively. Data points were fitted with one exponential function. Continuous and dotted lines represent the fit to the first and the second EPSC, respectively. E, an example of normalized and superimposed mean EPSC evoked at 0.05 (continuous line) and 1 Hz (dashed line) in one representative neuron. F, mean decay time constant of EPSC evoked at 0.05 and 1 Hz (n = 4).

NMDA receptors are not involved in short-term low frequency depression

Recently it has been reported that in the same preparation at CA3–CA3 connections, presynaptic action potentials (600 pulses) at 1 Hz associated with a slight depolarization (−55 mV) of the postsynaptic cell were able to induce a long-term depression (LTD) of EPSCs of almost 80 % (Montgomery & Madison, 2002). This effect required the activation of NMDA receptors and was prevented by the NMDA receptor antagonist AP5 (Montgomery & Madison, 2002). To see whether a similar type of mechanism could account for the present results, in four experiments LFD was induced in the presence of the NMDA receptor antagonist AP5 (50 μM). A similar degree of depression of EPSC1 was attained when the presynaptic firing was switched from 0.05 to 1 Hz (34 ± 6 and 40 ± 10 % in control and AP5, respectively). Also in the presence of AP5, this effect was associated with a reduction of the paired-pulse ratio (from 1.3 ± 0.3 to 0.82 ± 0.03, data not shown). In two cases, LFD was studied in the same pairs before and after application of AP5. Thus, after EPSC depression at 1 Hz and recovery, presynaptic firing was set again at 1 Hz in the presence of AP5. Also in these cases a similar degree of depression was obtained in control (31 ± 9 %) and in the presence of AP5 (28 ± 4 %). These data exclude the involvement of NMDA receptors in LFD.

DISCUSSION

The present results indicate that LFD is a common form of short-term synaptic plasticity at CA3–CA3 connections in hippocampal slice cultures. The reduction in synaptic strength varied across different connections according to presynaptic firing frequency and was associated with a modulation of the paired-pulse ratio, with PPD prevailing over PPF at higher stimulation frequencies.

Mechanisms of low-frequency synaptic depression

Frequency depression constitutes the predominant form of short-term dynamics in many CNS structures including sensorimotor cortex (Thomson et al. 1993; Abbott et al. 1997; Tsodyks & Markram, 1997), auditory pathways (von Gersdorff & Borst, 2002), cerebellum (Silver et al. 1998) and hippocampus (Dobrunz & Stevens, 1997). Although in the present experiments comparatively low frequencies were used, they were able to produce a gradual reduction in EPSCs amplitude. Moreover, especially at 1 Hz, synaptic depression could be so strong as to make synapses almost ‘silent’. The LFD observed here differed from the LTD recently described in the same preparation by Montgomery & Madison (2002) since responses recovered after switching to a low frequency stimulation. Unlike LTD, the induction of LFD was NMDA independent because it was insensitive to AP5. Moreover, LFD could be induced from a holding potential of −69 mV (including the correction for liquid junction potential, see Methods), while LTD from −55 mV.

As in other CNS structures (Thomson et al. 1993; Abbott et al. 1997; Tsodyks & Markram, 1997; Silver et al. 1998), use-dependent depression was found to be presynaptic in origin as suggested by the increase in failure rate and changes in PPR. Presynaptic mechanisms interfering with synaptic vesicle release include changes in action potential waveform, inactivation of calcium currents, modulation of presynaptic calcium channels by G-protein coupled receptors, etc. Changes in action potential waveform may depend on sodium channel inactivation. However, this mechanism does not seem to play a crucial role in paired-pulse depression under basal conditions (He et al. 2002). Moreover, the observation that small changes in spike amplitude were not associated with modifications in action potential half-width rules out sodium channel inactivation playing an important role in LFD (Brody & Yue, 2000; von Gersdorff & Borst, 2001). Presynaptic group II and III metabotropic glutamate receptors could potentially exert a strong inhibitory effect on transmitter release (Takahashi et al. 1996; von Gersdorff et al. 1997). These receptors, however, are not present on hippocampal associative commissural fibres (Berretta et al. 2000).

Although the locus of depression is likely to be presynaptic, a postsynaptic effect, such as receptor desensitization, cannot be completely ruled out. In our case, EPSC kinetics was unchanged under different stimulation frequencies, suggesting that modifications in AMPA receptor gating are not involved in this form of plasticity.

Frequency-dependent modulation of paired-pulse ratio

Several independent approaches suggest that both frequency depression and paired-pulse modulation depend largely on changes in release probability (Pr). A reduction in Pr during LFD predicts an increase in the PPR. Indeed, PPR has been shown to be enhanced when the extracellular calcium/ magnesium ratio was lowered (Debanne et al. 1996; Canepari & Cherubini, 1998). Unexpectedly, we found that PPF was converted into PPD. The reduction in PPR can be attributed to the activation of two temporally distinct processes: (i) modulation of the release probability by residual calcium and (ii) changes in size of the readily releasable pool of vesicles (Wu & Saggau, 1997; Dittman et al. 2000). The idea of expressing release probability as the balance between two processes, one related to the residual calcium and the other to vesicle availability, is similar in many aspects to that put forward by Zucker (1973), Quastel (1997) and Scheuss & Neher (2001). Unlike previously proposed models, we did not impose any constraint on the number of docked vesicles per release site, even though the model proposed by Zucker (1973) could lead to equations similar to those presented in the Appendix. Moreover, we did not consider desensitization (Scheuss & Neher, 2001), since our data exclude this possibility. Finally, in our model the interaction between paired-pulse ratio and stimulation frequency was described by a differential equation for the mean population of docked vesicles. It should be stressed that, although the number of docked vesicles may be related to the release probability (Dobrunz & Stevens, 1997), this cannot be generalised to all synapses (see Xu-Friedman et al. 2001).

According to our model, the probability of release at a single active zone (Pr) can be written as:

| (1) |

where Pr(Ca2+) and Pr(Ves) are the probability of release dependent on residual calcium and on the size of the available pool, respectively. The interplay between Pr(Ca2+) and Pr(Ves) at the moment of arrival of the second spike would determine the direction of the paired-pulse modulation (PPF or PPD). Thus, PPF observed in the majority of neurons in stationary conditions would be mainly dictated by the residual calcium (Zucker, 1989), being Pr(Ves) constant. In fact, at lower stimulation frequencies the size of the pool should be larger and any ‘loss’ of vesicles during the first pulse will be negligible. At higher stimulation frequencies, when the available pool becomes too small, an additional depletion due to the release from the first presynaptic spike in the paired-pulse protocol could diminish the size of the pool to such a critical level that at the moment of the arrival of the second spike Pr(Ves) would be close to zero. In this case, according to eqn (1), Pr would be close to zero independently of the value of Pr(Ca2+). Therefore, PPR is expected to increase at relatively low frequencies, and to decrease at higher frequencies when fewer vesicles are available for release. To validate these assumptions, a simple model has been developed (see Appendix). As predicted by the model in stationary conditions, when the time-dependent term of the process is neglected (f(t) of eqn (A8), Appendix), PPR is dependent on the frequency of stimulation (Fig. 5A). It is clear from the figure that the switch from PPF to PPD occurs between 0.1 and 1 Hz.

Figure 5. Expected frequency-dependent modulation of paired-pulse ratio.

A, stationary PPR obtained for different stimulation frequencies according to the proposed model (see eqn (A6), Appendix). B, predicted time course of the probability of release to the first (filled circles) and second pulse (open circles) at different stimulation frequencies. C, PPR calculated from the data of Fig. 4B for respective frequencies. PPR was obtained as the ratio between the mean values of p2 and p1. Model parameters: α= 0.48, γ= 0.28, nd = 18, λr = 0.0026 Hz, τ= 100 ms, Nc = 5.

The time dependency of the process is introduced by describing the dynamics of the population of docked vesicles via a first-order differential equation that considers both depletion and refilling of the pool. These two processes are characterized by time constants λd and λr, respectively (see also Scheuss & Neher, 2001). While λd depends on the stimulation frequency ω, the question as to whether λr also depends on the same factor is still open. Recently it has been suggested that the endocytosis rate, which influences the refilling of the pool (λr), depends on the frequency of stimulation (Sun et al. 2002). However, assuming that λr is independent of ω, we underestimated the frequency-dependent decrease in the mean pool size. The time course of the probability of release obtained at different frequencies (Fig. 5B) is similar to that of EPSC amplitudes obtained in experimental conditions, including the switch from PPF to PPD at 1 Hz. This suggests that a decrease in λr can account for our observations, without requiring changes in quantal size or in the number of release sites. By averaging the probability of release over all trials (at each frequency) an estimate of PPR in non-stationary conditions was obtained (Fig. 5C). As in experimental conditions (compare with Fig. 3C) PPR decreased with increasing frequency leading to PPD at 1 Hz. This effect fully recovered after switching to 0.025 Hz.

In conclusion, from our experiments it appears that presynaptic changes in Pr accounts for frequency-dependent synaptic depression. Release probability is directly correlated with a morphologically defined pool of docked vesicles (Dobrunz & Stevens, 1997; but see Xu-Friedman et al. 2001). The size of this pool would vary enormously between different synapses. This may account for the different time course of depletion and replenishment and for distinct frequency-dependent modulation of paired-pulse ratio found in various brain structures. Thus, a large pool of vesicles at the calyx of Held would ensure reliable synaptic transmission even at high frequencies when only a small fraction of synaptic vesicles are available for release (von Gersdorff et al. 1997).

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our gratitude to B. Gähwiler and L. Ballerini for helping us setting the hippocampal organotypic cultures. This work was supported by grants from Ministero dell'Università e Ricerca Scientifica (MURST) to E.C., from INTAS to E.C. and L.L.V. and from RFBR and the Welcome Trust to L.L.V.; L.P.S. was supported by the Program for Training and Research in Italian laboratories, International Center for Theoretical Physics, Trieste, Italy.

APPENDIX

The dependency of Pr on the size of the available pool can be written as:

| (A1) |

where k is a constant, p1 is the probability of release to the first pulse, λ the fusion rate for a vesicle integrated over the duration of the presynaptic pulse (Dobrunz & Stevens, 1997) and N is the number of ready releasable vesicles.

The probability of release to the second pulse (p2) is given by:

| (A2) |

where P2(1) is the probability of release to the second pulse, after release to the first and P2(0) the same probability after no release to the first pulse.

Taking into account also the effect of the residual calcium, we can write:

| (A3) |

and

| (A4) |

where α is a constant representing the sensitivity to residual calcium and τ is the time constant of decay of the higher probability of release, which is related to the rate of removal of residual calcium (Atluri & Regehr, 1996).

Hence the paired-pulse ratio is:

| (A5) |

Thus, by substituting P2(1), P2(0) and p1 from eqns (A3) and (A4) into eqn (A5):

| (A6) |

The number of available vesicles N can be modelled by writing:

| (A7) |

where λd and λr are the depletion and refilling constants, respectively, while Nc is the maximum size of the ready releasable pool of vesicles.

This equation states that there is a use-dependent depletion, whose rate depends on: (i) the frequency of stimulation (ω) with λd = ω/nd, and (ii) the refilling process controlled by λr. The solution of this first-order differential equation gives us the mean occupancy of each release site in our model synapse at time t:

| (A8) |

where the time-dependant term f(t) is equal to a exp(−(λd + λr)t) and the equilibrium term Neq is given by:

REFERENCES

- Abbott LF, Varela JA, Sen K, Nelson SB. Synaptic depression and cortical gain control. Science. 1997;275:220–224. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atluri PP, Regehr WG. Determinants of the time course of facilitation at the granule cell to Purkinje cell synapse. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:5661–5671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05661.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berretta N, Rossokhin AV, Kasyanov AM, Sokolov V, Cherubini E, Voronin LL. Postsynaptic hyperpolarisation increases the strength of AMPA mediated synaptic transmission at large synapses between the mossy fibres and CA3 pyramidal cells. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:2288–2301. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody DL, Yue DT. Release-independent short-term synaptic depression in cultured hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:2480–2494. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-07-02480.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canepari M, Cherubini E. Dynamics of excitatory transmitter release: analysis of synaptic responses in CA3 hippocampal neurons after repetitive stimulation of afferent fibers. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;79:1977–1988. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.4.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D, Guerineau NC, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Paired-pulse facilitation and depression at unitary synapses in rat hippocampus: quantal fluctuation affects subsequent release. Journal of Physiology. 1996;491:163–176. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittman JS, Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG. Interplay between facilitation, depression and residual calcium at three presynaptic terminals. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:1374–1385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01374.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrunz LE, Stevens CF. Heterogeneity of release probability, facilitation and depletion at central synapses. Neuron. 1997;18:995–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe ID, Clements JD. Presynaptic glutamate receptors depress excitatory monosynaptic transmission between mouse hippocampal neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1990;429:1–16. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gähwiler BH. Organotypic monolayer cultures of nervous tissue. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1981;4:329–342. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(81)90003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini S, Saviane C, Voronin LL, Cherubini E. Silent synapses in the developing hippocampus: lack of functional AMPA receptors or low probability of glutamate release. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2000;97:9741–9746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170032297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Zorumski CF, Mennerick S. Contribution of presynaptic Na+ channel inactivation to paired-pulse synaptic depression in cultured hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2002;87:925–936. doi: 10.1152/jn.00225.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkman AU, Jack JJB, Stratford KJ. Quantal analysis of excitatory synapses in rat hippocampal CA1 in vitro during low-frequency depression. Journal of Physiology. 1997;505:457–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.457bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Tsodyks M. Redistribution of synaptic efficacy between neocortical pyramidal neurons. Nature. 1996;382:807–810. doi: 10.1038/382807a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Wang Y, Tsodyks M. Differential signaling via the same axon of neocortical pyramidal neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:5323–5328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AC, Neher E, Schneggenburger R. Estimation of quantal size and number of functional active zones at the calix of Held synapse by nonstationary EPSC variance analysis. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:7889–7900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-07889.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery JM, Madison DM. State-dependent heterogeneity in synaptic depression between pyramidal cell pairs. Neuron. 2002;33:765–777. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Sakaba T. Combining deconvolution and noise analysis for the estimation of transmitter release rates at the calix of Held. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:444–461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00444.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Synaptic depression: a key player in the cortical balancing act. Nature Neuroscience. 1998;1:539–541. doi: 10.1038/2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls J, Wallace BG. Quantal analysis of transmitter release at an inhibitory synapse in the central nervous system of the leech. Journal of Physiology. 1978;281:171–185. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donovan MJ, Rinzel J. Synaptic depression: a dynamic regulator of synaptic communication with varied functional roles. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:431–433. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleskevich S, Clemens J, Walmsley B. Release probability modulates short-term plasticity at a rat giant terminal. Journal of Physiology. 2000;524:513–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00513.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis T, Zhang S, Trussel LO. Direct measurement of AMPA receptor desensitization induced by glutamatergic synaptic transmission. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:7496–7504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07496.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis P, Madison DV. Synaptic transmission in pair recordings from CA3 pyramidal cells in organotypic culture. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;81:2787–2797. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.6.2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quastel DM. The binomial model in fluctuation analysis of quantal neurotransmitter release. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:728–753. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(97)78709-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C, Stevens CF. Definition of the readily releasable pool of vesicles at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 1996;16:1197–1207. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuss V, Neher E. Estimating parameters from mean, variance, and covariance in trains of synaptic responses. Biophysical Journal. 2001;81:1970–1989. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75848-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver RA, Momiyama A, Cull-Candy SG. Locus of frequency dependent depression identified with multiple-probability fluctuation analysis at rat climbing fibre-Purkinje cell synapses. Journal of Physiology. 1998;510:881–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.881bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Wu X, Wu L. Single and multiple vesicles fusion induce different rates of endocytosis at a central synapse. Nature. 2002;417:555–559. doi: 10.1038/417555a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Forsythe ID, Tsujimoto T, Barnes-Davies M, Onodera K. Presynaptic calcium current modulation by a metabotropic glutamate receptor. Science. 1996;274:594–597. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AM, Deuchars J. Temporal and spatial properties of local circuits in neocortex. Trends in Neurosciences. 1994;17:119–126. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AM, Deuchars J, West DC. Large, deep layer pyramid-pyramid single axon EPSPs in slices of rat motor cortex display paired pulse and frequency-dependent depression, mediated presynaptically and self-facilitation mediated postsynaptically. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;70:2354–2369. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.6.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsodkys M, Markram H. The neural code between neocortical pyramidal neurons depends on neurotransmitter release probability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:719–723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Gersdorff H, Borst GJ. Short term plasticity at the calyx of Held. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3:53–64. doi: 10.1038/nrn705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Gersdorff H, Schneggenburger R, Weis S, Neher E. Presynaptic depression at a Calyx synapse: the small contribution of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:8137–8148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08137.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronin LL. On the quantal analysis of hippocampal long-term potentiation and related phenomena of synaptic plasticity. Neuroscience. 1993;56:275–304. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90332-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L-Y, Kaczmarek LK. High-frequency firing helps replenish the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles. Nature. 1998;394:384–388. doi: 10.1038/28645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L-J, Saggau P. Presynaptic inhibition of elicited neurotransmitter release. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:204–212. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu-Friedman MA, Harris KM, Regehr WG. Three-dimensional comparison of ultrastructural characteristics at depressing and facilitating synapses onto cerebellar Purkinje cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:6666–6672. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06666.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS. Changes in the statistics of transmitter release during facilitation. Journal of Physiology. 1973;229:787–810. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1989;12:13–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.12.030189.000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]