Abstract

The single photon response in vertebrate phototransduction is highly reproducible despite a number of random components of the activation cascade, including the random activation site, the random walk of an activated receptor, and its quenching in a random number of steps. Here we use a previously generated and tested spatiotemporal mathematical and computational model to identify possible mechanisms of variability reduction. The model permits one to separate the process into modules, and to analyze their impact separately. We show that the activation cascade is responsible for generation of variability, whereas diffusion of the second messengers is responsible for its suppression. Randomness of the activation site contributes at early times to the coefficient of variation of the photoresponse, whereas the Brownian path of a photoisomerized rhodopsin (Rh*) has a negligible effect. The major driver of variability is the turnoff mechanism of Rh*, which occurs essentially within the first 2–4 phosphorylated states of Rh*. Theoretically increasing the number of steps to quenching does not significantly decrease the corresponding coefficient of variation of the effector, in agreement with the biochemical limitations on the phosphorylated states of the receptor. Diffusion of the second messengers in the cytosol acts as a suppressor of the variability generated by the activation cascade. Calcium feedback has a negligible regulatory effect on the photocurrent variability. A comparative variability analysis has been conducted for the phototransduction in mouse and salamander, including a study of the effects of their anatomical differences such as incisures and photoreceptors geometry on variability generation and suppression.

INTRODUCTION

Vertebrate rod photoreceptors are capable of detecting the absorption of a single photon with a wavelength of ∼500 nm (1,2). Moreover, the resulting responses are highly reproducible, in the sense that the peak amplitudes and the shapes of the photocurrent as a function of time are very similar. Quantitatively, repeated single photon activations yield peak photocurrents with coefficient of variation (CV), defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean, of ∼20% (3,4). It is generally believed that a key contributor to this high fidelity of the single photon response (SPR) is the amplification part of the cascade (5–12).

One of the main points of this article is to challenge this assumption. We demonstrate that the diffusion of the second messengers cyclic guanosine-monophosphate (cGMP) and Ca2+ in the rod cytoplasm with characteristic complex geometry (13–15), after the activation of the photocascade, is the key determinant of the high reproducibility of the response.

The experimental results of the literature (6–8) have a photon as input and the photocurrent as output, and variability of the resulting photocurrent is statistically estimated. We show that the variation of the photocurrent is determined by two distinct modules, the activation cascade and the diffusion of cGMP and Ca2+, each contributing differently to the reproducibility of the response. Our modeling shows that the activation cascade and the random shutoff mechanism of a photoisomerized rhodopsin (Rh*) yields a CV of the total number of activated effectors, of ∼60%, whereas the diffusion of the second messengers reduces it to the observed 40% for the integration time and to ∼20% for the photocurrent at peak time. These two components, which cannot be distinguished using existing experimental techniques, can be mathematically separated into two modules and analyzed separately.

We show that the random walk of the Rh* after photoactivation, and the randomness of the activation site, contribute negligibly to the CV of the response. The main contributor to the variability seems to be the random shutoff mechanism of Rh*.

Finally, an experimentally observed CV of ∼20% for the current amplitude at peak time is obtained with Rh* shutting off through 2–3, at most, phosphorylated states. This is determined by numerical modeling and simulations of the CV as a function of the underlying biochemistry.

Molecules of receptor rhodopsin (Rh), transducin G-protein (T), and effector phosphodiesterase (E), are regarded as freely diffusing particles on the two-dimensional disk surface, each with their own specific diffusivity. The original signal of a single photon-activating molecule of Rh is amplified in the sense that an Rh* activates along its random walk, during the time it remains active, dozens of transducins (T → T*), by catalyzing GDP/GTP exchange on their α-subunit. Each molecule of T* associates, one-to-one, with a catalytic subunit of the effector forming a T*·E complex, denoted by E*, and called the activated-effector. The full-activation hypothesis postulates that a molecule of PDE is active only if both its subunits are bound to a molecule of T*. Thus, assuming full activation, [PDE*] = 1/2[E*].

A single molecule of E*, during its lifetime, hydrolyzes in excess of 50 molecules of the second messenger, cGMP (16,17). Diffusion of cGMP away from the cationic channels that it keeps open causes channel closure, and thereby suppresses the inward current. Low variability (high fidelity) of the SPR is experimentally assessed in terms of this photocurrent (3,4,6–8).

The strength of the output signal depends on the number of activated effectors E*, which in turn depends on the active lifetime of Rh*, and their own active lifetime. Inactivation of Rh* occurs essentially by two molecular events. First Rh* is phosphorylated by rhodopsin kinase (RK), by the sequential attachment of one or more phosphates at its C-terminal serine and threonine residues (18). Then phosphorylated Rh* is capped by arrestin (Arr), which shuts it off by making it inaccessible for T (19–22). The catalytic activity of E* terminates when activated transducin dissociates from the complex T*·E after its intrinsic GTPase hydrolyzes GTP to GDP. This latter process is greatly accelerated by RGS9 (23).

Absolute sensitivity of the visual system is limited by dark noise due to isomerization of Rh by thermal fluctuations and spontaneous activation of E (1,6,7,24–26). The system is so sensitive that it can act, at least for dim flashes, as a photon counter (27), permitting one absorbed photon to be distinguished from two (4).

This high reproducibility of SPR is intriguing, as the process contains several elements of randomness. For example, the disk activated by a quantum of light is a random one among the 1000 disks forming the rod outer segment (ROS); and the activation site is random within the activated disk; Rh* randomly diffuses within the activated disk, and remains active at random time tRh*. Finally, the number of Rh*-phosphorylations before quenching by arrestin is random.

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain low SPR variability. Among these is that tRh* has little effect on the process, that is, either tRh* is itself little-variable, or the photocurrent is relatively insensitive to variations of tRh* (8). Another is that a multistep Rh* shutoff stabilizes the output photocurrent (6,7,28).

It was pointed out in Pugh (10) that a full account of the single photon response has to include an analysis of the spatiotemporal diffusion of the second messengers cGMP and Ca2+ in the layered geometry of the ROS. This is the key point of this study. In a series of articles, we have created a mathematical and computational model of the spatiotemporal dynamics of cGMP and Ca2+ in the ROS by resolving the layered geometry. This was done by means of the mathematical theories of homogenization and concentrated capacity (13–15,29,30). The model is a tool that permits one, in almost real-time, to separate and check the effects of all the biochemical and physical parameters involved, even the random ones, including diffusivities, reaction rates, catalytic coefficients, and shutoff times. The geometrical parameters of the ROS including disk incisures, their shape, and their geometrical arrangements, can also be varied and their effects on the response can be calculated.

By means of this model, we separate and test the effects of the various random events contributing to the variability of the response. These include the random activation site, the random walk of Rh*, and the hypotheses of a multistep or abrupt random shutoff of Rh*.

We find that neither a random activation site nor a random walk of Rh* contribute significantly to the CV of E*; it is the multistep Rh* inactivation mechanism that is the main contributor to the CV. However, the number of steps in deactivation is not a main contributor to variability suppression. The surprising result of the simulations is that the diffusion of cGMP and Ca2+ damp out the variability of the SPR.

THE MATHEMATICAL MODEL

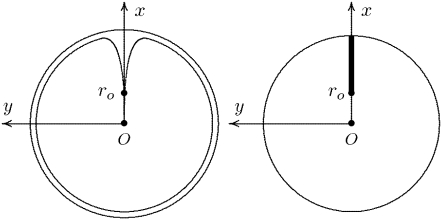

The dynamics of the second messengers cGMP and Ca2+ is modeled by taking the homogenized-concentrated limit of their physical, pointwise dynamics within the interdiscal spaces and in the outer shell. The limiting homogenized geometry is simpler in that the outer shell and the disks disappear and are replaced by dynamic equations on their limiting geometries, linked by equations expressing their mutual balance of fluxes. In particular, incisures in the homogenized-concentrated limit tend to segments Vj (Fig. 1). We denote by DR the disk of radius R and by Deff the effective domain of the activation cascade—that is, DR from which all the segments Vj have been removed:

|

We refer the reader to the literature (29,30) for the underlying mathematical analysis needed to compute such a homogenized-concentrated limit, and to the literature (13,15) for its biophysical significance. In Appendix A, we report the mathematical weak formulation of such a homogenized model, mainly to point out that

It is the starting point to writing a finite-elements code; and

It does not depend on the modeling of the activation cascade.

FIGURE 1.

(Left) Transversal cross section of the ROS bearing an incisure. (Right) Limit of such a cross section, bearing the limiting incisure V.

Indeed the function (x, y, t) → E*(x, y, t) for (x, y) ranging over an activated disk, serves as an input only, and its dynamic can be modeled independently. In this respect, the dynamics of the second messengers cGMP and Ca2+ is a module of the visual transduction cascade and the dynamics of the activated effector E* is a separate module.

Dynamics of the activation cascade

A molecule of rhodopsin, activated at time t = 0, becomes inactivated abruptly, after a random time tRh*, of average τRh*. During the random interval [0, tRh*), however, Rh* goes through n molecular states Rh*j, j = 1, …, n, each with transducin-activation rate νj, which remains constant as long as Rh* remains in the state Rh*j. For example, Rh*j might be in different phosphorylated states of Rh*, identified by the number (j – 1) of phosphates attached to Rh* by RK. The state (n + 1) is identified with Rh* being quenched by Arr binding. The transitions from the state j to (j + 1) occur at random transition times 0 < tj ≤ tn = tRh*, with νj remaining constant during the time interval (tj–1, tj], for j = 1, …, n, and where to = 0. Denote by δx(t) the Dirac mass in R2, concentrated at x(t) = (x(t), y(t)), and dimension μm−2, and by  the characteristic function of the interval (tj–1, tj]. Then the rate equations for T* and E* are

the characteristic function of the interval (tj–1, tj]. Then the rate equations for T* and E* are

|

(1) |

weakly in Deff × (0, T] (Appendix A), complemented by the initial data and the no-flux boundary conditions on ∂Deff as

|

(2) |

where n is the outward unit normal to ∂Deff, which is well defined except at the extremities of the limiting incisures Vj. It is assumed that the diffusivity of T and E is the same as that of their activated states. Thus, DT = DT* and DE = DE*. In the dark, T* and E* are uniformly distributed in Deff, with constant concentrations [T](0) and [E](0), respectively. At all (x, y) ∈ Deff and for all times, [E](0) is distributed into its active and inactive form, i.e.,

|

These stipulations and Eqs. 1 and 2 imply the conservation of mass,

|

(3) |

In Eq. 1, the constant kT*E is the rate of formation of the T*·E complex or equivalently the rate of formation of E*. The constant kE* is the rate of deactivation of E* by the hydrolysis of GTP by T*, within the T*·E complex. The constant kj, in s−1, is the constant of activation of T* by Rh* through a successful encounter at time t at the position x(t) on the random path of Rh*. The activation rate is proportional to the relative number ([T] – [T*])/[T] of transducin molecules available for activation. It is assumed that T*(x,y,t) ≪ [T](x,y,t) at all (x, y) ∈ Deff, and at all times, so that local depletion of T is negligible, which is true for dim light responses including SPR. Alternatively, at bright light the activation process obeys Michaelis-Menten kinetics with Michaelis constant K, and activation occurs in the saturation limit, i.e.,

|

Models like Eq. 1 involve deterministic parts, such as the diffusion processes appearing on the left-hand side, deterministic first-order reactions with given rates, and stochastic terms. Indeed, the transitions times tj for j = 1,…, n are random variables, and the path t → x(t) is random.

STATISTICS AND BIOCHEMISTRY

A newly created Rh* is in the state 1 (denoted by Rh*1). It undergoes a transition to the state 2 after some time s1, which is an exponentially distributed random variable with mean τ1. More generally, Rh* reaches the state j (denoted by Rh*j) after (j – 1) transitions from Rh*1. Then it undergoes a transition to the state (j + 1) after time sj has elapsed from the birth of Rh*j. The quantity sj is an exponentially distributed random variable with mean τj. After n transitions, Rh* is turned off, reaching the state n + 1. The random variables s1,…, sn are mutually independent; their sum, denoted by tRh*, is the lifespan of Rh*, which itself is a random variable with mean τRh*. The sj are connected to the transition times  and their mean values must satisfy

and their mean values must satisfy  The theoretical calculation of the probabilities Pj(t) of Rh* being in the jth state at time t, hinges upon the structure of the sequences of the mean times {τ1,…, τn}, and the catalytic constants {ν1,…, νn}. The structure of such sequences in turn depends on the underlying biochemistry. A theoretical choice could be that τj and νj are the same in each state. More biochemically motivated choices would allow for a {τj} and {νj} to be variable from state to state. The CV of some quantities can be computed theoretically, a priori, in terms of the sequences {νj} and {τj} irrespective of their structure (Appendix B). We will return to these explicit formulae in Eq. 14, to discuss their biochemical significance.

The theoretical calculation of the probabilities Pj(t) of Rh* being in the jth state at time t, hinges upon the structure of the sequences of the mean times {τ1,…, τn}, and the catalytic constants {ν1,…, νn}. The structure of such sequences in turn depends on the underlying biochemistry. A theoretical choice could be that τj and νj are the same in each state. More biochemically motivated choices would allow for a {τj} and {νj} to be variable from state to state. The CV of some quantities can be computed theoretically, a priori, in terms of the sequences {νj} and {τj} irrespective of their structure (Appendix B). We will return to these explicit formulae in Eq. 14, to discuss their biochemical significance.

Biochemical sequences {τj} and {νj}

Experimental evidence suggests that the phosphorylated states Rh*j are functionally different (31). In particular, their ability to activate T is different (32,33).

Shutoff of Rh* occurs by phosphorylation by RK, followed by Arr binding. Like many G-protein coupled receptors, rhodopsin contains multiple sites for phosphorylation in its C-terminus. The contribution of various phosphorylation sites to Rh* interaction with T, RK, and Arr has been addressed by several investigators, in a series of in vitro experiments (32,34–38). Biochemical experiments using the competition of synthetic phosphorylated and unphosphorylated rhodopsin C-terminal peptides suggest that phosphorylation of rhodopsin by RK is a cooperative process, i.e., the incorporation of one or two phosphates increases the probability of further phosphorylation (35). This phenomenon was rationalized in terms of increased affinity of the substrate for RK with increased phosphorylation (35). This should tend to favor the formation of multiphosphorylated rhodopsin species. Another study using full-length proteins (39) came to the opposite conclusion: that phosphorylation of rhodopsin and/or autophosphorylation of RK progressively decreases its affinity for light-activated rhodopsin. This mechanism could favor the accumulation of Rh* species with low level of phosphorylation. These models predict very different outcomes at high levels of illumination, when the number of Rh* molecules is comparable to the number of RK molecules in the photoreceptor, creating conditions where Rh* molecules compete for RK. However, under conditions relevant for our analysis where single photon responses are recorded, i.e., in the dark-adapted rod with only one Rh* and ≈200,000 molecules of RK (16), the difference between the predictions of these two models is negligible.

There is no consensus in the literature regarding the quantitative effect of progressive rhodopsin phosphorylation on transducin activation and arrestin binding (18,32,33). We based our choice for the sequences {τj} and {νj} on the data obtained with chromatographically separated rhodopsin species with different levels of phosphorylation (18,32), rather than on results obtained with complex mixtures of different phosphorhodopsin species (33). The catalytic activity of Rh* decreases with increasing levels of phosphorylation, at a rate of ∼12% for each additional level of phosphorylation (Fig. 2 in (32)). Thus,

|

(4) |

where νRG is the catalytic activity of Rh*, and j is the level of phosphorylation. The mean resting times τj are assumed to be equal, except for the first, nonphosphorylated state. The first resting time τ1 is longer, as several biochemical processes have to occur before the first phosphorylation. At dark concentrations of Ca2+, recoverin is in the Ca2+-bound form at the membrane, and forms a complex with RK, blocking its activity (16). As [Ca2+] drops, recoverin releases Ca2+, and dissociates from RK, which permits the phosphorylation of Rh* (16,34). For the mouse it is reported in Mendez et al. (40) that Rh* remains in its unphosphorylated state, for ∼100 ms or ∼1/2tpeak, and then it deactivates in two or three states, each of comparable length, with decreasing catalytic constants. A recent study (23) provided definitive proof that the observed dominant time constant of recovery (t = 200 ms) reflects RGS9-assisted GTP hydrolysis by transducin α-subunit. Increasing expression of RGS9 in rods progressively reduces this constant. However, eventually the constant reaches a new limit, 80 ms, beyond which further increases in RGS9 expression could not reduce it, indicating that some other step became rate-limiting (23). The molecular nature of this second-slowest step has not been identified. It could be the maximum catalytic rate of transducin-RGS9 complex, the rate of the release of PDE from T-GDP, the rate of rebinding of PDE to PDE, or the rate of rhodopsin inactivation. However, this time constant determines the upper limit of the Rh* lifetime, which includes sequential phosphorylation by RK to appropriate level (18) and arrestin binding. Taking this information into account, we choose

|

(5) |

Simulations for these choices of {τj} and {νj} are referred to in captions and legends as nonequal times and nonequal catalytic rates (NN). Relative length of the steps that reflect rhodopsin phosphorylation by RK and of the last step that involves arrestin binding depends on the concentrations of RK and arrestin in the outer segment (OS) in the dark (SPR is recorded in fully dark-adapted animals). RK concentration was recently estimated at 12 μM (16). The estimates of the amount of arrestin present in the OS in the dark vary from 1–3% (41,42) to <7% of the total (43). The estimated rhodopsin concentration in the OS is ∼3 mM (16) and arrestin is expressed at 0.8:1 ratio to rhodopsin (42,43). So if 1, 2, 3, or 7% of arrestin is present in the OS in the dark, it translates into 24, 48, 72, or 168 μM concentrations, which at first glance look very different. However, based on the self-association constants (44), one can calculate that at any of these concentrations a significant proportion of arrestin would be in the form of dimer and tetramer, with ∼45, 30, 22, and 14%, respectively, being a monomer, which is the only form of arrestin capable of binding rhodopsin (44). This yields the concentrations of the active monomer in dark-adapted OS of 11, 14, 16, and 23 μM, respectively. Thus, the concentrations of active RK (after the decrease of Ca2+ removes recoverin-mediated brake) and of active arrestin monomer are comparable. Therefore the length of the last step (between the last phosphorylation and arrestin binding) can be assumed to be close to the lengths of the preceding phosphorylation steps, with the exception of step 1 (unphosphorylated Rh*), which is longer.

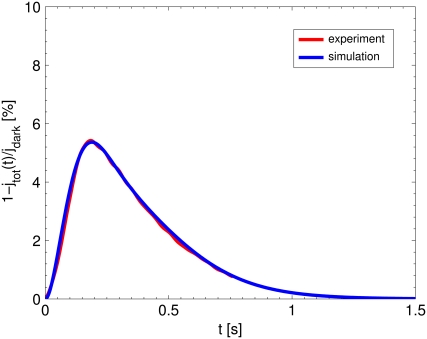

FIGURE 2.

The red curve reports the average of an extensive set of experimental SPR responses for mouse, kindly provided to us by F. Rieke. The blue curve is our numerical simulation of the mouse SPR using the mathematical model of Appendix A for the set of parameters in Table 3. The agreement is excellent, thereby showing that this selection parameters accurately reflects the timecourse and amplitude of experimentally generated light responses.

Sequence for which τjνj = const

This choice is often made (6,7,9,45,46), although it is purely theoretical and is not motivated by known biochemistry. Let E** denote the random total number of molecules of E* produced over the entire time duration of the process, after a single isomerization. In Appendix B, a theoretical formula has been derived for CV(E**), regardless of the structure of the sequences {τj} and {νj} (Eq. 15). This equation implies that if νjτj = const for all j = 1, … , n, then

|

(6) |

A CV of the order of  has been reported in several contributions (6,7,9,46), although it was not precisely defined to which function it relates (molecules of E*, lowest cGMP concentration, peak current, or something else). To compare our approach with the existing literature, we have performed simulations for sequences {νj} and {τj} satisfying Eq. 6 and for which, in addition,

has been reported in several contributions (6,7,9,46), although it was not precisely defined to which function it relates (molecules of E*, lowest cGMP concentration, peak current, or something else). To compare our approach with the existing literature, we have performed simulations for sequences {νj} and {τj} satisfying Eq. 6 and for which, in addition,

|

(7) |

This stipulates that the phosphorylated states of Rh* last, on average, an equal amount of time tRh*/n, and that the catalytic rates νj are the same in each state. Simulations for these choices of {τj} and {νj} are referred to in captions and legends as equal times and equal catalytic rates (EE). To be sure, Eq. 6 is satisfied by infinitely many choices of {νj} and {τj} for which neither νj nor τj is constant, but their product is (See More on statistics and biochemistry in Appendix B).

RANDOM EVENTS CONTRIBUTING TO SPR VARIABILITY

A code for Eq. 1 presents two major difficulties. The first is the incised geometry of Deff, which is dealt with by mathematical methods of numerical analysis. The second is the stochastic input on the right-hand side of the first equation in Eq. 1. This includes the random activation site, the random path of Rh*, and random shutoff mechanism. The model permits one to test independently the effects of these random components on the variability of the response. For example, one can separate the effects of the activation site and the subsequent random walk of Rh* on Deff from the shutoff mechanism. Also, one can separate the effects of the shutoff mechanism from the Brownian motion of Rh*. To achieve this, we performed the following sets of simulations:

Case 1

Fix the activation site xo ∈ Deff and let Rh* follow its random Brownian path t → x(t) starting at x(0) = xo, with a prescribed second moment of its probability density. The shutoff time tRh* and the number n of states before ultimate quenching, are fixed. The mean half-lives of different states could be equal or different, and still deterministically fixed. It turns out that if one regards the activation site as random, its mean position is at distance 2/3 of the radius of the activated disk. Thus, in this case,  The only random effect in this case is that of the Brownian motion of Rh*.

The only random effect in this case is that of the Brownian motion of Rh*.

Case 2

The activation site xo is random and Rh* remains fixed at its initial location. The shutoff time tRh* and the number n of steps before quenching are fixed. The only randomness is the position of the activation site, which discriminates responses from each other.

Case 3

The activation site  is fixed and also Rh* remains fixed at xo. Quenching of Rh* occurs at the random shutoff time tRh*, in n states. Random numbers τj are selected according to their exponential distribution and subject to either the statistic of Eq. 5 or 7, and the probabilities Pj(t), for j = 1,…, n, are computed accordingly (Appendix B). These simulations separate the random effects of the shutoff mechanism from those of the activation sites and the motion of Rh*.

is fixed and also Rh* remains fixed at xo. Quenching of Rh* occurs at the random shutoff time tRh*, in n states. Random numbers τj are selected according to their exponential distribution and subject to either the statistic of Eq. 5 or 7, and the probabilities Pj(t), for j = 1,…, n, are computed accordingly (Appendix B). These simulations separate the random effects of the shutoff mechanism from those of the activation sites and the motion of Rh*.

Case 4

All the previous components are random (activation site, random path of Rh*, random shutoff time tRh* for a given number of steps). This is the biologically realistic case, although the previous cases extract the impact of each component of randomness.

FUNCTIONALS DETECTING THE SPR VARIABILITY

A MATLAB-based, finite-element code has been written for the system in Eqs. 1–3, based on its weak formulation (Appendix A). The output E*, as a function of the two variables (x, y) ∈ Deff and time t, is then fed into the code for the homogenized system describing the dynamics of the second messengers (Appendix A). Finally, local and global currents generated across the ROS lateral surface, are computed by the formulae

|

(8) |

In the first of these,  is the saturated exchange current (as [Ca2+] → ∞), Kex is the Ca2+ concentration at which the exchange rate is half-maximal, and Σrod is the surface area of the lateral boundary Sɛ of the ROS. In the second,

is the saturated exchange current (as [Ca2+] → ∞), Kex is the Ca2+ concentration at which the exchange rate is half-maximal, and Σrod is the surface area of the lateral boundary Sɛ of the ROS. In the second,  is the maximal cGMP-current (as [cGMP] → ∞), mcG is the Hill exponent, and KcG is the binding affinity of each cGMP binding site on the channel. Notice that Jex and JcG are current densities (i.e., current per unit area, measured in pA/μm2), and, in general, have different values at different points of the lateral boundary Sɛ of the ROS. In the absence of light, Jex and JcG are constant and equal to their constant, dark values Jex;dark and JcG;dark defined as in Eq. 8 with [Ca2+] and [cGMP] replaced by [Ca2+]dark and [cGMP]dark, respectively. Introduce cylindrical coordinates (θ, z) on the outer shell Sɛ where z ranges over (0, H) and θ ranges over [0, 2π). The local value of (total) current density Jloc and its dark value Jdark are defined as

is the maximal cGMP-current (as [cGMP] → ∞), mcG is the Hill exponent, and KcG is the binding affinity of each cGMP binding site on the channel. Notice that Jex and JcG are current densities (i.e., current per unit area, measured in pA/μm2), and, in general, have different values at different points of the lateral boundary Sɛ of the ROS. In the absence of light, Jex and JcG are constant and equal to their constant, dark values Jex;dark and JcG;dark defined as in Eq. 8 with [Ca2+] and [cGMP] replaced by [Ca2+]dark and [cGMP]dark, respectively. Introduce cylindrical coordinates (θ, z) on the outer shell Sɛ where z ranges over (0, H) and θ ranges over [0, 2π). The local value of (total) current density Jloc and its dark value Jdark are defined as

|

(9) |

The corresponding global quantities are defined as integrals over the lateral boundary of the ROS, i.e.,

|

(10) |

where dS is the surface measure of the lateral boundary of the ROS.

While Jloc(θ, z, t) is pointwise current defined on the outer shell, experimentally what is measured is the global current jtot(t) as a function of time, and what is graphed is the relative local or global current drop,

|

(11) |

The variability of the SPR will be analyzed by measuring the variability of the effector and the photocurrent separately and then by comparing them. The natural variable functionals of the effector E* are

|

(12) |

The last three are scalar quantities and their CV is reported in Table 1. The first two are functions of time. The CV of the second, as a function of time, will be reported in Fig. 3, A and C, and Fig. 4, A and C. The natural variable functionals of the photocurrent are

|

(13) |

While the last one is a consequence of the first, we have listed it separately since this is the experimental quantity actually being measured (6–8). The last three are scalar quantities and their CV is tabulated in Table 2. The first two are functions of time. The CV of the second is graphed as a function of t in Fig. 3, B and D, and Fig. 4, B and D. The quantity I** is the total relative charge produced over the entire timecourse of the phenomenon after isomerization by a single photon. In Field and Rieke (28) it is argued that the “…area captures fluctuations occurring at any time during the response, and thus provides a good measure of the total extent of response fluctuations…”. Pointwise fluctuations are tracked by I(t) and I*(t). The very same quantity I**, when normalized by the peak response amplitude I(tpeak), is referred to as integration time, and reported as a measure of variability in a number of articles (8,22,31,40,46–48).

TABLE 1.

CV (σ/μ) for E**, E*(t*peak), and t*peak

| E**

|

E*(t*peak)

|

t*peak

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mech. | Species | Incisure | Case | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| NN | Mouse | N | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 3 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.68 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.49 | |||

| 4 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.67 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.49 | |||

| Y | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 3 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.68 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.49 | |||

| 4 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.67 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.49 | |||

| Salamander | N | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 3 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.69 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.54 | |||

| 4 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.57 | 0.55 | |||

| Y | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 3 | 0.71 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.52 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.68 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.54 | |||

| 4 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.54 | |||

| EE | Mouse | N | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 3 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.69 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.43 | |||

| 4 | 0.69 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.68 | 0.56 | 0.48 | 0.43 | |||

| Y | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 3 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.69 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.43 | |||

| 4 | 0.69 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.68 | 0.56 | 0.48 | 0.43 | |||

| Salamander | N | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 3 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.68 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.44 | |||

| 4 | 0.70 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.68 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.43 | |||

| Y | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 3 | 0.71 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.68 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.43 | |||

| 4 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.43 | |||

NN, Shutoff of Rh* in n biochemical states of decreasing duration and catalytic activity (see Biochemical Sequences {τj} and {νj}); EE, Shutoff of Rh* in n theoretical states of equal duration and equal catalytic activity (see Sequence for Which τjνj = Const); Y, Yes; and N, No.

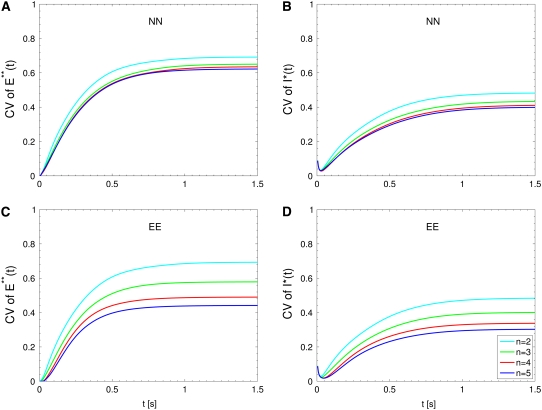

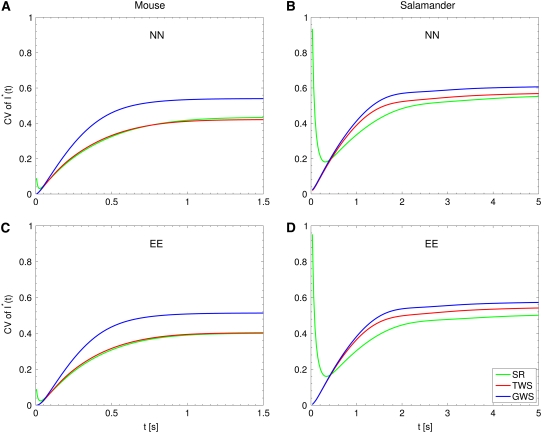

FIGURE 3.

Mouse: comparing the CV of the total activated effectors  at time t with the CV of the total relative charge

at time t with the CV of the total relative charge  up to time t. (NN) Shutoff of Rh* in n biochemical states of decreasing duration and catalytic activity (see Biochemical Sequences {τj} and {νj}). (EE) Shutoff of Rh* in n theoretical states of equal duration and equal catalytic activity (see Sequence for Which τjνj = Const). All simulations assume all activation steps as random (Case 4 of Random Events Contributing to SPR Variability). In all cases, CV decreases with increasing n. (A and B) For the biochemical state NN, the CV of both E**(t) and I*(t) stabilizes asymptotically after 3–4 phosphorylated states. A CV of ∼60% for E**(t) at times past the peak time is reduced to a CV of ∼40% for the corresponding photocurrent I*(t). (C and D) For the theoretical state EE, increasing n gives in all cases a decreased CV although at a decreasing rate for increasing n. The CV comparison E**(t) (∼60%) to I*(t) (∼40%) is still present, thus pointing to an intrinsic variability reduction effect of the diffusion part of the process.

up to time t. (NN) Shutoff of Rh* in n biochemical states of decreasing duration and catalytic activity (see Biochemical Sequences {τj} and {νj}). (EE) Shutoff of Rh* in n theoretical states of equal duration and equal catalytic activity (see Sequence for Which τjνj = Const). All simulations assume all activation steps as random (Case 4 of Random Events Contributing to SPR Variability). In all cases, CV decreases with increasing n. (A and B) For the biochemical state NN, the CV of both E**(t) and I*(t) stabilizes asymptotically after 3–4 phosphorylated states. A CV of ∼60% for E**(t) at times past the peak time is reduced to a CV of ∼40% for the corresponding photocurrent I*(t). (C and D) For the theoretical state EE, increasing n gives in all cases a decreased CV although at a decreasing rate for increasing n. The CV comparison E**(t) (∼60%) to I*(t) (∼40%) is still present, thus pointing to an intrinsic variability reduction effect of the diffusion part of the process.

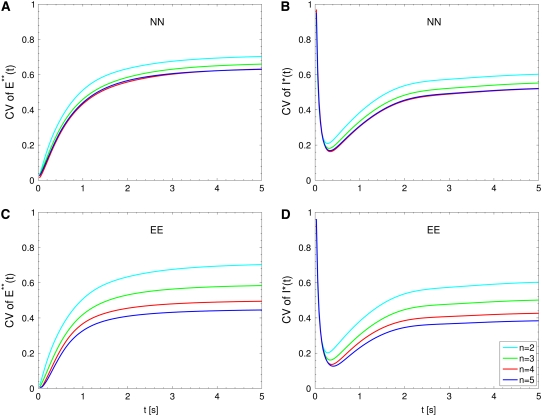

FIGURE 4.

Salamander: comparing the CV of the total activated effectors  at time t with the CV of the total relative charge

at time t with the CV of the total relative charge  up to time t. (NN) Shutoff of Rh* in n biochemical states of decreasing duration and catalytic activity (see Biochemical Sequences {τj} and {νj}); (EE) Shutoff of Rh* in n theoretical states of equal duration and equal catalytic activity (see Sequence for Which τjνj = Const). All simulations assume all activation steps as random (Case 4 of Random Events Contributing to SPR Variability). In all cases, CV decreases with increasing n. For NN, the CV stabilizes for n ≥ 3 and it is essentially the same for n = 3, 4, 5. For EE, the CV keeps decreasing with increasing n, although at a decreasing rate for increasing n. For the salamander at early times, the CV is initially large and then rapidly drops. No similar effect occurs in mouse. (A and B) For the biochemical state NN, the CV of both E**(t) and I*(t) stabilizes asymptotically after 3–4 phosphorylated states. A CV of ∼60% for E**(t) at times past the peak time is reduced to a CV of ∼50% for the corresponding photocurrent I*(t). (C and D) For the theoretical state EE, increasing n gives in all cases a decreased CV although at a decreasing rate for increasing n. The CV comparison E**(t) (∼60%) to I*(t) (∼50%) is still present, thus pointing to an intrinsic variability reduction effect of the diffusion part of the process. The suppression of CV for the photocurrent I*(t) with respect to CV of the activating E**(t), while present, is less dramatic than for mouse (Fig. 3, A and B). In addition, we observe a sharp variability at early times, which is likely due to presence of the incisures and their distributed geometry. This is supported by the absence of such incipient CV, in lumped models insensitive to incisures geometry (see also captions of Fig. 5). This early-time high CV seems also to be due to the random position of the activation site. Indeed, photons absorbed close to the disk boundary, yield a faster response than those absorbed far away from the boundary, say near the center of the disk. After a short time, depending on the diffusivity coefficients on the disk and on the disk radius, this difference is reduced. In the mouse, where diffusivities are larger and the radius is smaller than similar parameters in the salamander, no significant increase of variability at early times is observed (see also Fig. 3).

up to time t. (NN) Shutoff of Rh* in n biochemical states of decreasing duration and catalytic activity (see Biochemical Sequences {τj} and {νj}); (EE) Shutoff of Rh* in n theoretical states of equal duration and equal catalytic activity (see Sequence for Which τjνj = Const). All simulations assume all activation steps as random (Case 4 of Random Events Contributing to SPR Variability). In all cases, CV decreases with increasing n. For NN, the CV stabilizes for n ≥ 3 and it is essentially the same for n = 3, 4, 5. For EE, the CV keeps decreasing with increasing n, although at a decreasing rate for increasing n. For the salamander at early times, the CV is initially large and then rapidly drops. No similar effect occurs in mouse. (A and B) For the biochemical state NN, the CV of both E**(t) and I*(t) stabilizes asymptotically after 3–4 phosphorylated states. A CV of ∼60% for E**(t) at times past the peak time is reduced to a CV of ∼50% for the corresponding photocurrent I*(t). (C and D) For the theoretical state EE, increasing n gives in all cases a decreased CV although at a decreasing rate for increasing n. The CV comparison E**(t) (∼60%) to I*(t) (∼50%) is still present, thus pointing to an intrinsic variability reduction effect of the diffusion part of the process. The suppression of CV for the photocurrent I*(t) with respect to CV of the activating E**(t), while present, is less dramatic than for mouse (Fig. 3, A and B). In addition, we observe a sharp variability at early times, which is likely due to presence of the incisures and their distributed geometry. This is supported by the absence of such incipient CV, in lumped models insensitive to incisures geometry (see also captions of Fig. 5). This early-time high CV seems also to be due to the random position of the activation site. Indeed, photons absorbed close to the disk boundary, yield a faster response than those absorbed far away from the boundary, say near the center of the disk. After a short time, depending on the diffusivity coefficients on the disk and on the disk radius, this difference is reduced. In the mouse, where diffusivities are larger and the radius is smaller than similar parameters in the salamander, no significant increase of variability at early times is observed (see also Fig. 3).

TABLE 2.

CV (σ/μ) for I**, I(tpeak), and tpeak

| I**

|

I(tpeak)

|

tpeak

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mech. | Species | Model | Incisure | Case | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| NN | Mouse | SR | N | 3 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| 4 | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.15 | ||||

| Y | 3 | 0.48 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.19 | |||

| 4 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.19 | ||||

| TWS | N | 4 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.21 | ||

| Y | 4 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.21 | |||

| GWS | 4 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.26 | |||

| Salamander | SR | N | 3 | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.16 | |

| 4 | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.18 | ||||

| Y | 3 | 0.60 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.16 | |||

| 4 | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.16 | ||||

| TWS | N | 4 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.19 | ||

| Y | 4 | 0.66 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.19 | |||

| GWS | 4 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.21 | |||

| EE | Mouse | SR | N | 3 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.15 |

| 4 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.15 | ||||

| Y | 3 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.17 | |||

| 4 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.17 | ||||

| TWS | N | 4 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.19 | ||

| Y | 4 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.21 | |||

| GWS | 4 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.22 | |||

| Salamander | SR | N | 3 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.13 | |

| 4 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.15 | ||||

| Y | 3 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.14 | |||

| 4 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.14 | ||||

| TWS | N | 4 | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.16 | ||

| Y | 4 | 0.66 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.16 | |||

| GWS | 4 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.17 | |||

NN, Shutoff of Rh* in n biochemical states of decreasing duration and catalytic activity (see Biochemical Sequences {τj} and {νj}); EE, Shutoff of Rh* in n theoretical states of equal duration and equal catalytic activity (see Sequence for Which τjνj = Const); SR, space-resolved; TWS, transversally well-stirred; GWS, globally well-stirred; Y, Yes; and N, No.

PROCEDURES AND METHODS

The selection of one of the cases in Random Events Contributing to SPR Variability determines the right-hand side of the Eq. 1, and the corresponding biochemistry and statistics. Then the code computes the functions Deff∋(x, y) → E*(x, y, t) at each time t ≥ 0, the currents in Eqs. 8–11, via [cGMP] and [Ca2+], and then the local and global relative drops (Eq. 10). After a large number of these numerical experiments (∼1000), one computes the mean, the standard deviation, and the CV of the functionals indicated in Functionals Detecting the SPR Variability.

Each of these numerical experiments is carried for ROS with incisures and without incisures, as a way of investigating their functional role. A comparative analysis has been conducted for salamander and mouse, following the experimental results of Rieke and Baylor (6) for amphibians, and of Field and Rieke (28) for mammals.

Finally the simulations are run with clamped calcium, to test the hypothesis put forth in the literature (6,8,46) that calcium feedback does not affect the variability of SPR.

Parameters

For the salamander, a reasonably complete set of parameters has been compiled in the literature (14,15). In Table 3, we have generated a complete, self-consistent set of parameters for the mouse ROS, partly taken from the literature, partly generated by comparative consideration with other higher vertebrate (bovine), and partly computed from the experimental data for mouse SPR kindly provided by Dr. F. Rieke. We discuss here a few points related to the choice of these parameters. The parameters used in the model of the diffusion of Ca2+ and cGMP in the cytosol (see Weak Formulation of the Dynamics of cGMP, and Weak Formulation of the Dynamics of Ca2+) are taken from the literature (14,15).

TABLE 3.

Parameters for the Mouse ROS

| Symbol | Units | Definition | Range | Value | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| αmax | μM s−1 | Maximum rate of cGMP synthesis at low Ca2+ concentration. | 76.5; 55.9 | 76.5 | (70,71) |

| αmax/αmin | — | Suppression ratio of α from high to low Ca2+ concentration. | 6.7–13.9 | 13.9 | (70–72) |

| Ainc | μm2 | Area of the incisure. | 0.0367 | ||

| βdark | s−1 | Rate of cGMP hydrolysis by dark activated PDE. | 1.5–10 | 2.9 | (31,47,71) |

| BcG | — | Buffering power of cytoplasm for cGMP. | 1–2 | 1 | (16,17,49) |

| BCa | — | Buffering power of cytoplasm for Ca2+. | 17.5–44 | 20 | (49,61,64) |

| cGE | — | Coupling coefficient from G* to E*. | <1 | 1 | (16,54) |

| [cGMP]dark | μM | Concentration of cGMP in the dark. | 2–4 | 3.0748 | (16,17,49,62,71–74) |

| [Ca2+]dark | nM | Concentration of Ca2+ in the dark. | 200–670 | 436.2 | (16,47,75–82) |

| DcG | μm2 s−1 | Diffusion coefficient for cGMP. | –500 | 150 | (14,55,59) |

| DCa | μm2 s−1 | Diffusion coefficient for Ca2+. | 15 | 15 | (64) |

| DE* | μm2 s−1 | Diffusion coefficient for activated PDE. | 1.2 | 1.2 | (17) |

| DG* | μm2 s−1 | Diffusion coefficient for activated G protein. | 2.2 | 2.2 | (17) |

| DR* | μm2 s−1 | Diffusion coefficient for activated Rh. | 1.5 | 1.5 | (17) |

| ɛ | nm | Disk thickness. | 14–17 | 14.5 | (17,57,83) |

| η | nm | Volume/surface ratio. | 7.25 | ||

| ℱ | Cmol−1 | Faraday's constant. | 96,500 | 96,500 | |

| fCa | — | Fraction of cGMP-activated current carried by Ca2+. | 0.06–0.17 | 0.06 | (16,31,70,84,85) |

| H | μm | Height of ROS. | 20–24 | 23.6 | (16,57,86,87) |

| jdark | pA | Dark current. | 8.2–21 | 13.24 | (16,22,40,47,48,70,72,88–94) |

|

pA | Maximum cGMP-gated channel current. | 3550 | ||

|

pA | Saturated exchanger current. | 1–2 | 1.8 | (95–97) |

| kcat/Km | μM−1 s−1 | Hydrolytic efficiency of activated PDE dimer. | 450–820 | 540 | (17,54,98) |

| kσ;hyd | μm3 s−1 | Surface hydrolysis rate of cGMP by dark-activated PDE. | 2.8 × 10−5 | ||

| k*σ;hyd | μm3 s−1 | Surface hydrolysis rate of cGMP by light-activated PDE. | 0.75–1.37 | 0.9 | |

| kE | s−1 | Rate constant for inactivation of PDE. | 5–11.5 | 6 | (23,31,47,99) |

| kR | s−1 | Rate constant for inactivation of Rh. | 1.4–11 | 8.5 | (47,61) |

| kT*E | μm2 s−1 | Kinetic constant describing the formation of T*·E complex and thus the production of E*. | 1 | 1 | (9) |

| Kcyc | nM | Half-saturating [Ca2+] for GC activity. | 73–400 | 129 | (31,47,70,71) |

| KcG | μM | [cGMP] for half-maximum cGMP-gated channel opening. | 20 | (16) | |

| Kex | μM | [Ca2+] for half-maximum exchanger channel opening. | 0.9–1.6 | 1.6 | (16,96) |

| lb | μm | Width of the incisure. | 0.2593 | (56) | |

| lr | μm | Length of the incisure. | 0.2828 | (56) | |

| ν | — | Ratio between interdiscal space and disk thickness. | 0.56–1 | 1 | (16,17,54,57) |

| νɛ | nm | Interdiscal space. | 14.5 | (17,57,86,87) | |

| νRE | s−1 | Rate of PDE formation per fully activated Rh. | 120–220 | 170 | (16,46,49,54) |

| νRG | s−1 | Rate of transducin formation per fully activated Rh. | 120–220 | 170 | (16,46,49,54) |

| n | # | Number of disks. | 814 | ||

| ninc | # | Number of incisures. | 1 | 1 | (17,56,57) |

| NAv | #mol−1 | Avogadro number. | 6.02 × 1023 | 6.02 × 1023 | |

| mcyc | — | Hill coefficient for GC effect. | 2.3–4 | 2.45 | (31,47,70–72) |

| mcG | — | Hill coefficient for cGMP-gated channel. | 3 | 3 | (17,47,71,72,92) |

| [PDE]σ | #μm−2 | Surface density of dark-activated PDE. | 500–1000 | 750 | (16,17,83,86,100) |

| R | μm | Radius of disk. | 0.45–1 | 0.7 | (16,17,57,68,83,86,87,101) |

| σ | — | Ratio between outer shell thickness and disk thickness. | 15:14.5 | ||

| σε | nm | Distance between the disk rim and the plasma membrane (outer shell thickness). | 15 | 15 | (17,59) |

| Σrod | μm2 | Lateral surface area of ROS. | 103.8 | ||

| Vcyt | μm3 | Cytoplasmic volume. | 18.16 |

There is considerable uncertainty about the parameters appearing in Eq. 1, and describing the diffusion of E* and T* in the activated disk. These include surface diffusion coefficients DE* and DT* of activated effector and transducin; the rate-constant kE of inactivation of E* through the activation of RGS9 to stimulate the GTP hydrolysis of T*; the rate kT*E of activation of E* by G*; and the constants kj, for j = 1, … , n, which are the rates of activation of G* by Rh*. Finally, though not explicitly appearing in Eq. 1, two more parameters are needed in the model: the diffusivity and the average lifetime of activated rhodopsin.

The parameter kE is the inactivation rate of the G*·E* complex, and identifies the dominant time constant τE = 1/kE, in the recovery process. That is, τE is the time constant for inactivation of the G*·E* complex. For salamander, it is reported to be τE ≈ 1.5 s (49,16). In the simulations, we have taken kE ≈ 0.64 s−1 as in Nikonov et al. (49).

Let  and

and  denote the surface diffusion coefficients of Rh*, G*, and E*, on the activated disks. The value of these parameters has been estimated in Pugh and Lamb (17), both for amphibians and mammals. The diffusion theory put forth in Pugh and Lamb (17) is based on the simplifying assumption that both Rh* and E* remain still, while G* diffuses. In Caruso et al. (15), we adapted this approach, by selecting E* as the only mobile species. The advantage is that the reaction diffusion system describing the motion of G* and E* can be replaced by a single equation, for [PDE*], where the reaction term due to the presence of Rh* appears as a fixed source. This, however, would lead to underestimating the overall activation of E, since this reaction is essentially diffusion-controlled. To compensate for this unwanted effect, we augment the diffusion coefficient of the activated effector by replacing it with the sum of the three diffusivities,

denote the surface diffusion coefficients of Rh*, G*, and E*, on the activated disks. The value of these parameters has been estimated in Pugh and Lamb (17), both for amphibians and mammals. The diffusion theory put forth in Pugh and Lamb (17) is based on the simplifying assumption that both Rh* and E* remain still, while G* diffuses. In Caruso et al. (15), we adapted this approach, by selecting E* as the only mobile species. The advantage is that the reaction diffusion system describing the motion of G* and E* can be replaced by a single equation, for [PDE*], where the reaction term due to the presence of Rh* appears as a fixed source. This, however, would lead to underestimating the overall activation of E, since this reaction is essentially diffusion-controlled. To compensate for this unwanted effect, we augment the diffusion coefficient of the activated effector by replacing it with the sum of the three diffusivities,  and

and  This compensation mechanism is analogous to a similar argument in Pugh and Lamb (17). Notice that the choice of these parameters has to discriminate between Cases 1 and 4, and Cases 2 and 3. In the latter group of simulations, we continue to assume that Rh* remains fixed, but the activation and diffusion of transducin is taken explicitly into account. For this reason, as in the literature (15,17), the diffusion coefficient for G* is taken as the sum of

This compensation mechanism is analogous to a similar argument in Pugh and Lamb (17). Notice that the choice of these parameters has to discriminate between Cases 1 and 4, and Cases 2 and 3. In the latter group of simulations, we continue to assume that Rh* remains fixed, but the activation and diffusion of transducin is taken explicitly into account. For this reason, as in the literature (15,17), the diffusion coefficient for G* is taken as the sum of  and

and  and no correction is required in the remaining part of the cascade. Thus, in Eq. 1, one has

and no correction is required in the remaining part of the cascade. Thus, in Eq. 1, one has  and

and  Instead, in Cases 1 and 4, the simplifying assumption that Rh* stays still is dropped, and we account for each reaction diffusion step in the cascade separately. Then, each diffusion coefficients is set equal to its experimentally estimated value (17). Thus, in particular,

Instead, in Cases 1 and 4, the simplifying assumption that Rh* stays still is dropped, and we account for each reaction diffusion step in the cascade separately. Then, each diffusion coefficients is set equal to its experimentally estimated value (17). Thus, in particular,  and

and

The diffusivity of rhodopsin, although it does not appear explicitly in Eq. 1, is used in generating a random walk of the activated molecule. A second hidden parameter is the mean τRh*, of the random lifetime tRh* of Rh*. Although the general scheme of rhodopsin inactivation has been well established in vitro and is widely used as a paradigm for the inactivation of a larger family of G-protein-coupled receptors, there are no conclusive experimental measurements of the timecourse of Rh* inactivation in vivo. For salamander, Lyubarsky et al. (50) have argued that the inactivation time constant of Rh* is ∼0.4 s. For mouse, Lyubarsky and Pugh (51) found the effective lifetime of Rh* is ≤0.21 s, and an estimate of 0.15 s was also reported. The most recent estimate, based on the assumption that when the deactivation of transducin is progressively accelerated by increasing expression of RGS9, the inactivation of Rh* becomes rate-limiting, yielded 80 ms as a half-life of Rh* (23). Based on data obtained in recordings of human ERGs, Hood and Birch et al. (52) have argued that the lifetime of Rh* is ≈2 s.

The parameter ν1 on the right-hand side of the first part of Eq. 1 is referred to in the literature as νRE, that is, the rate of activation of effector per Rh*, bypassing the role of G*. The value of νRE has been extracted from the published data (16,49,53). This parameter would remain constant along the full activation-deactivation phases if the effects of the different functional species of Rh* were not accounted for.

The kinetic constant KT*E is the rate of formation of the T*·E complex, through which E* is generated. Leskov et al. reported an essentially 1:1 coupling between G* and PDE* (16,54). Thus, it is reasonable to assume KT*E = 1 μm2 s−1/# and νRE = νRG.

The numerical ranges of the parameters DT* and DE*, as well as kj, kT*E, and kE, and their choices in our simulations are collected in Tables 3 and 4.

TABLE 4.

Parameters for the Salamander ROS

| Symbol | Units | Definition | Range | Value | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| αmax | μM s−1 | Maximum rate of cGMP synthesis at low Ca2+ concentration. | 40–50 | 50 | (16,49) |

| αmin/αmax | — | Ratio of αmin to αmax. | 0.00–0.02 | 0.02 | (16,49) |

| Ainc | μm2 | Area of the incisure. | 0.82 | 0.8 | (55) |

| βdark | s−1 | Rate of cGMP hydrolysis by dark-activated PDE. | 1 | 1 | (14–16,49) |

| BcG | — | Buffering power of cytoplasm for cGMP. | 1–2 | 1 | (16,17,49) |

| BCa | — | Buffering power of cytoplasm for Ca2+. | 10–50 | 20 | (16,49,61) |

| cGE | — | Coupling coefficient from G* to E*. | <1 | 1 | (16,54) |

| [cGMP]dark | μM | Concentration of cGMP in the dark. | 2–4 | 3.0046 | (49,62) |

| [Ca2+]dark | nM | Concentration of Ca2+ in the dark. | 400–700 | 653.7 | (49,62) |

| DcG | μm2 s−1 | Diffusion coefficient for cGMP. | 50–196 | 160 | (14,55,63) |

| DCa | μm2 s−1 | Diffusion coefficient for Ca2+. | 15 | 15 | (64) |

| DE* | μm2 s−1 | Diffusion coefficient for activated PDE. | 0.8 | 0.8 | (17) |

| DG* | μm2 s−1 | Diffusion coefficient for activated G protein. | 1.5 | 1.5 | (17) |

| DR* | μm2 s−1 | Diffusion coefficient for activated Rh. | 0.7 | 0.7 | (17) |

| ɛ | nm | Disk thickness. | 10–14 | 14 | (16,62) |

| η | nm | Volume/surface ratio. | 7 | ||

| F | Cmol−1 | Faraday's constant. | 96,500 | 96,500 | (16,49) |

| fCa | — | Fraction of cGMP-activated current carried by Ca2+. | 0.1–0.2 | 0.17 | (16,49) |

| H | μm | Height of ROS. | 20–28 | 22.4 | (16,62) |

| jdark | pA | Dark current. | 74 | 65.862 | (16) |

|

pA | Maximum cGMP-gated channel current. | 70–7000 | 7000 | (49) |

|

pA | Saturated exchanger current. | 17–20 | 17 | (16) |

| kcat/Km | μM−1 s−1 | Hydrolytic efficiency of activated PDE dimer. | 340–600 | 400 | (17,49,54) |

| kσ;hyd | μm3 s−1 | Surface hydrolysis rate of cGMP by dark-activated PDE. | — | 7 × 10−5 | (14) |

| k*σ;hyd | μm3 s−1 | Surface hydrolysis rate of cGMP by light-activated PDE. | — | 1 | (13,14) |

| kE | s−1 | Rate constant for inactivation of PDE. | 0.58–0.76 | 0.6 | (61) |

| kR | s−1 | Rate constant for inactivation of Rh. | 1.69–3.48 | 2.5 | (61) |

| kT*E | μm2 s−1 | Kinetic constant describing the formation of T*·E complex and thus the production of E*. | 1 | 1 | (9) |

| Kcyc | nM | Half-saturating [Ca2+] for GC activity. | 100–230 | 135 | (49,62) |

| KcG | μM | [cGMP] for half-maximum cGMP-gated channel opening. | 13–32 | 20 | (16,49,62) |

| Kex | μM | [Ca2+] for half-maximum exchanger channel opening. | 1.5; 1.6 | 1.5 | (49,62) |

| lb | nm | Width of the incisure. | 10–12 | 15 | (55) |

| lr | μm | Length of the incisure. | 4.6377 | (15) | |

| ν | — | Ratio between interdiscal space and disk thickness. | 1 | ||

| νɛ | nm | Interdiscal space. | 10–14 | 14 | (16,62) |

| νRE | s−1 | Rate of PDE formation per fully activated Rh. | 120–220 | 195 | (16,46,49,54) |

| νRG | s−1 | Rate of transducin formation per fully activated Rh. | 120–220 | 195 | (16,46,49,54) |

| n | # | Number of disks. | 1000 | 800 | (49,62) |

| ninc | # | Number of incisures. | 15–30 | 23 | (55,65–69) |

| NAv | #mol−1 | Avogadro number. | 6.02 × 1023 | 6.02 × 1023 | |

| mcyc | — | Hill coefficient for GC effect. | 2 | 2 | (16,54,63) |

| mcG | — | Hill coefficient for cGMP-gated channel. | 2–3 | 2.5 | (16) |

| [PDE]σ | #μm−2 | Surface density of dark-activated PDE. | 100 | 100 | (16) |

| R | μm | Radius of disk. | 5.5 | 5.5 | (49,62) |

| σ | — | Ratio between outer shell thickness and disk thickness. | 15:14 | (49,62) | |

| σɛ | nm | Distance between the disk rim and the plasma membrane (outer shell thickness). | 15 | 15 | (49,62) |

| Σrod | μm2 | Lateral surface area of ROS. | 773.5 | (62) | |

| Vcyt | μm3 | Cytoplasmic volume. | 1000 | 1076 | (16,62) |

The incisures have been simulated as follows:

Salamander. Twenty-three incisures symmetrically distributed along the edge of the disk. Each is an isosceles triangle, which starts from the edge with width 15 nm and runs radially toward the center of the disk with the height of 4.64 μm. The total area exposed by the incisures is 0.8 μm2. These parameters have been taken from Olson and Pugh (55) and elaborated in Caruso et al. (15).

Mouse. One incisure, shaped as an isosceles triangle of base 0.2593 μm, height 0.2828 μm, and area 0.0367 μm2. These values are taken from the literature (17,56,57) and are elaborated and justified in Caruso et al. (15).

Parameter calibration

The parameters are calibrated by least-square fitting of the simulated response current to the experimental data. In the calibration, it is assumed that Rh* is shut off exponentially in one step. When enforcing the multiple step shutoff for Rh*, in either the EE or NN mechanism, the simulation response currents diverge from the best-fitting curve. To keep the best fitting, we restore the simulation response current by slightly adjusting the value of νRE. The calibration is minimal, and the parameters always remain within the published range of νRE (120 ∼ 220 s−1 (16,46,49,54). These adjustments have little or no effect on the CV of E*, and response current I(t) for the following reasons:

All the remaining parameters have been kept unchanged; and

The adjustments of νRE amount to an equal multiplication factor to each of the νj.

The latter has no effect on the CV of E**, in view of the explicit formula (Eq. 15).

VARIABILITY OF E*

Table 1 reports the CV for the scalar quantities E**, t*peak, and E*(t*peak) defined in Eq. 12 for each of the cases indicated in Random Events Contributing to SPR Variability, and for an Rh* shutoff mechanism occurring in n = 2, 3, 4, 5 steps. The first result is that for Cases 1 and 2, the CV of any of these quantities is essentially zero. Thus, neither the randomness of the activation site nor the random walk of Rh* contribute to the CV of E*. For the mouse, the presence or absence of incisures does not affect the CV of E*. For the salamander, the presence of incisures tends to slightly reduce the CV of E*. The reduction is ∼1%. This effect is most likely due to the different geometry of the ROS for mouse and salamander. Mice have long and thin ROS with one incisure, exposing only a modest area. The complement of the incisure is essentially the whole disk. Salamander ROS have a large cross section bearing up to 30 incisures, exposing a relatively large area. We believe that their number, more than the area they expose, is responsible for a slightly reduced CV; indeed, they tend to create essentially equal compartments, and rhodopsin activated by a photon captured in one of them tends to remain there, thereby yielding a more reproducible response.

The multistep deactivation mechanism of Rh* seems to be responsible for the CV of E*. Moreover the CV produced by Case 3, to which only the randomness of the shutoff mechanism contributes, seems to be roughly the same as that of Case 4, where all components are allowed to be random. In all cases, CV decreases with increasing n. For the biochemical choice of the NN mechanism, the largest CV drop occurs when the number of steps to shutoff goes from 2 to 3. As the number of inactivation steps further increases to 4 and 5, the CV remains essentially the same.

Instead, for the theoretical choice of EE, an increase in the number of shutoff steps from 3 to 5 yields a decrease of CV by up to 12%. For the case EE, the theoretical formula (Eq. 15) predicts a CV for E** of  irrespective of the values of the parameters. Accordingly, the simulated CV for E** reported in Table 1 is exactly

irrespective of the values of the parameters. Accordingly, the simulated CV for E** reported in Table 1 is exactly  both for mouse and salamander, within possible relative statistical errors <1%.

both for mouse and salamander, within possible relative statistical errors <1%.

The comparison of the CV of E**,  and

and  for the biochemically motivated case NN and the theoretical case EE demonstrates that when the number n of Rh* shutoff steps increases, the latter produces a more stable process. For n = 2, the CV of these quantities is essentially the same for the NN and EE cases. Since n increases to 3,4,5, it is higher for NN than for EE by up to 35%, for n = 4, 5. Thus, the EE biochemistry produces a process more stable than the realistic biochemistry NN—most likely because of a more regular distribution of times τj and because the catalytic constants νj are all equal to νRE.

for the biochemically motivated case NN and the theoretical case EE demonstrates that when the number n of Rh* shutoff steps increases, the latter produces a more stable process. For n = 2, the CV of these quantities is essentially the same for the NN and EE cases. Since n increases to 3,4,5, it is higher for NN than for EE by up to 35%, for n = 4, 5. Thus, the EE biochemistry produces a process more stable than the realistic biochemistry NN—most likely because of a more regular distribution of times τj and because the catalytic constants νj are all equal to νRE.

In Fig. 3, A and C, and Fig. 4, A and C, we report the graphs of the CV for E**(t) as functions of time only for Case 4. Indeed, this is the biologically realistic case, where all the parts of the phenomenon are permitted to be random. This variability functional is defined in Eq. 12.

In all cases, the CV decreases with increasing n. For the case of the biochemistry NN, there is a drop in CV in going from two shutoff steps of Rh* to n = 3. For mechanisms with a number of phosphorylations n ≥ 3, the CV of E**(t) is essentially indistinguishable for n = 3, 4, 5. Within the timecourse of the phenomenon (≈1.8 s for the salamander and ≈0.5 s for the mouse), the CV of E**(t) does not exceed 0.5, at least for n ≥ 3, and as t → ∞, it tends asymptotically to ≈0.6.

For the theoretical biochemistry EE, the decrease of CV for n going from 2 to 3, 4, and 5 is more dramatic, although from 4 to 5 the drop in CV is approximately half of that for the preceding values of n. Within the timecourse of the phenomenon, the CV of E**(t), for Rh* shutting off in either 4 or 5 steps, does not exceed 0.4—and as t → ∞, it tends asymptotically to ≈0.42, even for n = 4, 5.

In all cases, despite the different geometry of the disks, including the different distribution of incisures, the CV of E**(t) for mouse and salamander are comparable.

VARIABILITY OF THE PHOTOCURRENT

In Table 2 we have reported the CV of the scalar quantities I**, I(tpeak), and tpeak, defined in Eq. 13 for each of the Cases 3 and 4 indicated in Random Events Contributing to SPR Variability, and for an Rh* shutoff mechanism occurring in n = 2, 3, 4, 5 steps. We do not report the simulations for Cases 1 and 2 that record the random effects of the activation site and the random walk of Rh*. As shown in Table 1, these effects have a negligible effect of the CV of I**, I(tpeak), and tpeak. These random components, which have a negligible effect by themselves, affect the system more noticeably when coupled with the random shutoff of Rh*. This becomes apparent by comparing the Case 3 (randomness only due to shutoff mechanism) and Case 4 (all components are allowed to be random; see Table 2). The results exhibit a pattern similar to those in Table 1, although at considerably lower values of CV.

The biochemistry of NN

In all cases, there is a drop in CV of 10–15% in going from n = 2 to n = 3, and then for n = 3, 4, 5 the CV tends to remain virtually constant. This suggests that an increase in the number of steps in the shutoff process of Rh* to >3–4 steps does not significantly decrease the CV of these functionals, which remain within 2–3% of each other. For the salamander, the presence of incisures increases the CV of I** by 8–13%, and the CV of I(tpeak) by 2–10%. However, the CV of tpeak decreases slightly (by ≤5%). Thus, in terms of photocurrent the presence of incisures in the salamander ROS tends to generate a less stable system and in terms of peak time a slightly more stable system. This is likely explained by more efficient and rapid diffusion of cGMP afforded by the vertical shafts created by the incisures. The effects of incisures in the mouse are similar with reduced quantitative impact, except that in the presence of incisures, the CV of tpeak also increases.

The biochemistry EE

The results for the theoretical case EE are similar, except that the CV of the various functionals decrease as n increases, although at a decreasing rate for increasing n. The pattern suggest an asymptotic limit as n → ∞ for these CV. It is worth noting that for the mouse, the CV of I(tpeak) for n = 5 is smaller than the experimental values reported in the literature (6,8,10,58). This suggests that even assuming the biochemistry EE, the number of steps to Rh* to quenching is limited. It also suggests that the analysis of the CV of the SPR cannot be based only on the number n of steps postulated to shutoff of Rh*; rather, it would require a stipulation on the nature of these steps, which we have translated in the structure of the sequences {νj} and {τj}.

Lumped models

Table 2 contains two extra sets of simulations labeled by the transversally well-stirred (TWS) model and the globally well-stirred (GWS) model, as opposed to the space-resolved (SR) model. The latter corresponds to the model we are using in these simulations, originating from homogenization and concentrated capacity, as described in the literature (13,15,29,30). The TWS model lumps all quantities in the ROS along its longitudinal axis, and takes into account only the diffusion of the second messengers cGMP and Ca2+ along this axis. The GWS model lumps together all quantities as each satisfying global first-order reactions, devoid of any spatial characteristics, such as geometry, diffusion in interdiscal spaces, etc.

In the literature (13,15) we have described how to obtain the GWS model from the SR model, and how to simulate with them and compare the outputs. The main reason we report the results of these simulations is that the GWS model is the most commonly used (16,49) because of its mathematical and computational simplicity, and the TWS model is sometimes used as the first attempt to take into account the spatiotemporal features of the system (53,59).

For the salamander, for the biochemistry NN, there is a relative difference of ≥10% between the CV calculated with the SR model and the TWS model. That difference increases to 20–40% in going from the SR to the GWS model. Discrepancies of the same order or larger occur for the theoretical biochemistry EE (Table 2). In all cases, the CV computed with the coarser models TWS and GWS is larger, and it increases with the coarseness of the model. In particular, the more the model is well stirred, the larger is the CV. Thus, lumped models yield a variability larger than what is physically expected, due to the damping effects of the diffusion process. The latter are being detected and factored in by our the SR model.

The CV of the photocurrent over the timecourse of the response

Fig. 3, B and D, and Fig. 4, B and D, report the CV of the total relative charge produced up to time t, for the physically realistic Case 4, where all random components are present. In all cases, CV decreases with increasing n. However, for the biochemistry NN, the CV stabilizes for n ≥ 3 and it is essentially the same for n = 3, 4, 5. For the theoretical EE case, the CV keeps decreasing with increasing n, although at a decreasing rate for increasing n, and points to some theoretical asymptotic behavior as n → ∞. Fig. 5 compares the CV of the total relative charge up to time t computed with the SR model to the CV of the same quantity computed by the TWS and GWS models. In all cases, the CV computed with the GWS model is higher than the one computed with the other two models.

FIGURE 5.

CV of  : total relative charge up to time t. (SR) Space-resolved; (TWS) transversally well-stirred; (GWS) globally well-stirred; (NN) shutoff of Rh* in n biochemical states of decreasing duration and catalytic activity (see Biochemical Sequences {τj} and {νj}); and (EE) shutoff of Rh* in n theoretical states of equal duration and equal catalytic activity (see Sequence for Which τjνj = Const). All simulations assume all activation steps as random (Case 4 of Random Events Contributing to SPR Variability). In all cases, the CV computed with the GWS model is higher than the one computed with the other two models. A high CV at early times for the salamander, detected by the SR model (where geometry and incisures matter), is not detected by the lumped models TWS and GWS. This suggests the interpretation that a high CV at the inception of the activation cascade is due to the architecture of the salamander ROS.

: total relative charge up to time t. (SR) Space-resolved; (TWS) transversally well-stirred; (GWS) globally well-stirred; (NN) shutoff of Rh* in n biochemical states of decreasing duration and catalytic activity (see Biochemical Sequences {τj} and {νj}); and (EE) shutoff of Rh* in n theoretical states of equal duration and equal catalytic activity (see Sequence for Which τjνj = Const). All simulations assume all activation steps as random (Case 4 of Random Events Contributing to SPR Variability). In all cases, the CV computed with the GWS model is higher than the one computed with the other two models. A high CV at early times for the salamander, detected by the SR model (where geometry and incisures matter), is not detected by the lumped models TWS and GWS. This suggests the interpretation that a high CV at the inception of the activation cascade is due to the architecture of the salamander ROS.

A peculiar, apparently reverse effect, can be observed for the salamander, at early times. The CV is initially large and then rapidly drops. This effect seems to be due to the random position of the activation site. Indeed, photons absorbed close to the disk boundary yield a faster response than those absorbed far away from the boundary, say near the center of the disk. After a short time, depending on the diffusivity coefficients on the disk and on the disk radius, this difference is reduced. In the mouse, where diffusivities are larger and the radius is smaller than similar parameters in the salamander, no significant increase of variability at early times is observed.

DISCUSSION

Rods are highly polarized, and intricately organized, neuronal cells, with elaborate outer segment structure. There is a precise geometry of stacked disks in the cytoplasm, with elaborate precisely aligned incisures that serve to facilitate the longitudinal diffusion of second messengers (15). Rod disks house the integral membrane and peripheral membrane proteins that perform photon capture and chemical amplification of the visual signal. Perturbations of this complex cellular architecture lead to retinal degeneration by triggering apoptosis (60).

We recently introduced a mathematical model of the dynamics of visual transduction that incorporates the precise geometry of outer segments. To make this phenomenon computationally tractable, the model reduced the complex geometry of the outer segment to a simpler one by separating the two-dimensional diffusion of molecules on disks and plasma membrane from the three-dimensional cytoplasmic diffusion. Using this model, we were able to capture fine spatial and temporal dynamics of visual transduction. The computational implementation of the model has allowed us to reproduce the local effects that characterize rod signaling in response to light. This has provided a quantitative assessment of the notion of spread of excitation (13,14), and of the impact of the activation site on the single photon response. In particular, these studies showed that variation in single photon responses that were thought to be random, can be accounted for to some degree, by the distance of the site at which the photon hits from the plasma membrane.

Recently we took advantage of the capabilities of this model to study the role of incisures, intricate structures that are held together with bivalent proteins called peripherin/retinal degeneration-slow, or (rds). Our modeling showed that incisures allowing for larger cytoplasmic spaces, favor the longitudinal diffusion of cGMP and Ca. This effect leads to larger light-responses, and depends on the number of incisures and their geometry.