Abstract

Many studies show agreement within and between cultures for general judgements of facial attractiveness. Few studies, however, have examined the attractiveness of specific traits and few have examined preferences in hunter-gatherers. The current study examined preferences for symmetry in both the UK and the Hadza, a hunter-gatherer society of Tanzania. We found that symmetry was more attractive than asymmetry across both the cultures and was more strongly preferred by the Hadza than in the UK. The different ecological conditions may play a role in generating this difference. Such variation in preference may be adaptive if it reflects adaptation to local conditions. Symmetry is thought to indicate genetic quality, which may be more important among the Hadza with much higher mortality rates from birth onwards. Hadza men who were more often named as good hunters placed a greater value on symmetry in female faces. These results suggest that high quality Hadza men are more discriminating in their choice of faces. Hadza women had increased preferences for symmetry in men's faces when they were pregnant or nursing, perhaps due to their increased discrimination and sensitivity to foods and disease harmful to a foetus or nursing infant. These results imply that symmetry is an evolutionarily relevant trait and that variation in symmetry preference appears strategic both between cultures and within individuals of a single culture.

Keywords: facial attractiveness, asymmetry, culture, Hadza, cross-cultural agreement

1. Introduction

An evolutionary view of human facial attractiveness posits that certain traits are indicators of mate value—the degree to which an individual could enhance the fitness of their partner. These traits may indicate good health, fertility, physical and/or behavioural dominance, even pro-social investment. It might therefore be expected that, if some cues are reliably associated with mate value, there would be agreement among humans on which faces are attractive and unattractive. Indeed, across many studies considerable agreement is found within a particular culture, as well as across different cultures (e.g. Cunningham et al. 1995; see Langlois et al. (2000), for a meta-analytic review). Such studies have generally only examined an agreement on global attractiveness (i.e. is one face more attractive than another face) and such studies have usually examined urban university-based populations.

While there is much agreement on which faces are attractive and unattractive, it has also become apparent that there are predictable individual differences in preferences for some facial traits (Little et al. 2001, 2002). If there are differences between individuals of the same culture, there may also be differences between cultures. Darwin (1871) was struck by cultural differences in attractiveness criteria, such as preferences for skin colour, body hair, body fat and practices such as lip ornamentation and teeth filing. Such convictions were supported by early cross-cultural work by Ford & Beach (1951) who catalogued differences between cultures in preferences for various aspects of female physique.

In the current study, we examine preferences for facial symmetry as this trait is potentially linked to evolutionarily relevant aspects of mate value. Fluctuating asymmetry (Valen 1962) is thought to reflect an individual's ability to maintain the stable development of their morphology under the prevailing environmental conditions. In urban Western samples, studies of real (Scheib et al. 1999; Penton-Voak et al. 2001) and manipulated faces (Perrett et al. 1999; Little & Jones 2003) show that symmetry is found attractive. While the issue is controversial, many studies do show links between symmetry and quality including factors such as growth rate, fecundity and survivability (Møller 1990, 1997), and one study has shown that more asymmetrical men and women reported more health problems (Thornhill & Gangestad 2006).

These data may imply that all individuals should prefer symmetry. However, such a preference could also carry a cost, which may then change the value of symmetry according to circumstance. It has been argued that humans have variable mating strategies, with preferences changing in response to environmental and life-history factors (Gangestad & Simpson 2000). One aspect of this argument is that high quality males should be less willing to provide paternal investment than males who are less preferred by women. In terms of symmetry preference, we might therefore expect that individuals that are relatively more interested in high quality offspring (genetically) would have stronger preferences for symmetry than for help in provisioning. Symmetry preferences may then vary between cultures where parental investment is more important and those where resistance to disease is more important.

Two studies have examined symmetry preferences across cultures using manipulated faces. Kowner (1996) examined the attractiveness of manipulated symmetry in Japanese participants, demonstrating that Japanese participants preferred the unmanipulated, slightly asymmetric versions (although symmetry was preferred in elderly faces). The manipulation used by Kowner, reflecting the face along the vertical midline, is known to create unusual but symmetric faces, with for example, any incorrect placing of the midline creating large or small noses in the resulting symmetric images (see Perrett et al. 1999).

A more recent and more technically sophisticated study (manipulating symmetry by blending each face with its mirror image) has shown that symmetry of faces is found attractive in Japanese faces in Japan (Rhodes et al. 2001). Thus, while compatible with the view that there is cross-cultural agreement, the current data on cross-cultural preferences for symmetry are few and limited to affluent societies. The explanations put forward by Rhodes et al. (2001) to explain similarity in preference are that similar visual experience between cultures could explain agreement or a similar pressure to choose symmetric partners has led to preferences in both cultures.

(a) Rationale

Previous studies of cross-cultural preferences for symmetry have been limited to urban societies with exposure to modern media. We examined preferences for symmetry in opposite-sex faces in the Hadza, a hunter-gatherer society from northern Tanzania in East Africa and from UK participants. The Hadza live under conditions very different from those generally assessed. The Hadza have very limited exposure to modern media and, as foragers depend on acquiring wild foods, they live under radically different circumstances to people in Western cultures. The Hadza live under potentially more challenging ecological conditions (Gray & Marlowe 2002). For example, they sleep outside on the ground, have greater daily physical exertion and have limited access to medical care. Living outside in the tropics where pathogens are more prevalent (Low 1990) means that they are exposed to more pathogens. There are also potential differences in investment in partners between the two cultures. Any or all of these differences are variables that could generate differences in facial preferences. If symmetry is an important, sexually selected trait we should expect it to be preferred across cultures.

We were also interested in variability in symmetry preferences among the Hadza. Preferences for symmetry have been found to vary according to the attractiveness of the perceiver, with women who think they are attractive preferring more symmetric male faces (Little et al. 2001). Here, we collected data on perceptions of male quality by the Hadza with the prediction that those men who were seen as attractive would be relatively more choosy about symmetry in faces. Limited data were collected on Hadza women but data were available on whether women were pregnant and/or nursing. Given that previous studies have found pregnancy increases preferences for healthy appearing faces and decreases preferences for masculinity (Jones et al. 2005), we examined this variable in relation to symmetry preference.

2. Material and methods

(a) Participants

The Hadza are mobile hunter-gatherers who number approximately 1000. They live in a savannah-woodland habitat in Northern Tanzania and have camps that average approximately 30 individuals. The camp membership continually changes as people move in and out. The camps generally move to different locations about once every one to two months. Women dig for wild tubers, gather berries and collect baobab fruit while men hunt prey and collect honey. Most Hadza are monogamous, though approximately 4% of men have two wives.

Hadza participants were recruited from three separate camps and were interviewed in private by one of the authors (C.L.A.). The Hadza are fluent in Swahili and the interviews were conducted in Swahili. European participants were recruited over the Internet via a mailing list. All European participants reported being heterosexual and were volunteers.

Seventy-eight European participants from the UK (39 males, 39 females, aged 18–44, mean age=24.4, s.d.=5.6) and 42 Hadza participants from Tanzania (21 males, 21 females, aged 20–56, mean age=33.6, s.d.=9.6) took part in the study.

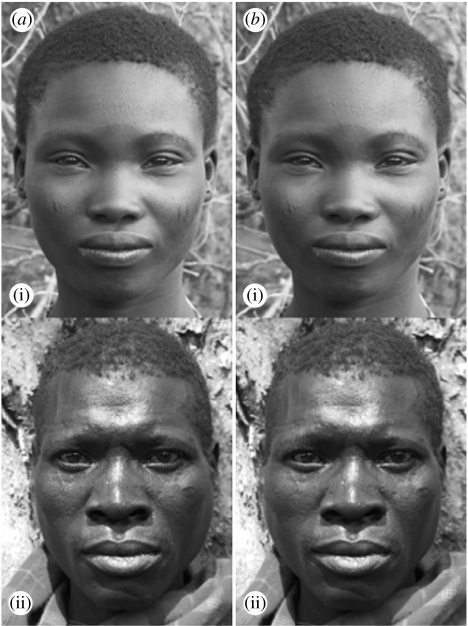

(b) Stimuli

Five original male and five original female face images were selected for each race from larger sets of photographs White European images were taken under standardized lighting at the same distance from the camera. Hadza images were taken under natural lighting conditions in the field and at a variable distance from the camera. Images were selected for the faces to be looking directly at the camera to minimize asymmetries due to head tilt. The test was made up of a pair of images, one original and one symmetric. All images were manipulated to match the position of the left and right eyes by standardizing the interpupillery distance. To generate the symmetric images, original images were morphed so that the position of the features on either side of the face was symmetrical. Images maintained original textural cues and were symmetric in shape alone (see Perrett et al. (1999) for technical details). An example of an original and symmetrical Hadza face can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Examples of symmetrized (a(i,ii)) and original (b(i,ii)) male and female Hadza faces.

We measured horizontal and vertical asymmetries from the unmanipulated images using established measurement techniques (for details see Penton-Voak et al. (2001)). Univariate ANOVAs were conducted with race of face and sex of face as fixed factors which revealed no significant effects of either variable for horizontal symmetry (all F1,16<0.23, p>0.64) or vertical symmetry (all F1,16<1.68, p>0.21) suggesting that the asymmetry in the unmanipulated faces was equivalent for all types of face.

(c) Procedure

All participants were presented with face pairs of the opposite sex. European and Hadza individuals participated in different ways though the instructions and images were equivalent. The Europeans had the faces presented electronically on a computer screen and the test was self-administered. The Hadza had the test administered to them on photographic quality printed cards. Both Europeans and Hadza had unlimited time to complete their judgements. The face pairs were presented in random order with participants being asked to choose from the pair ‘which face is most attractive?’. For each trial, presentation of symmetric/asymmetric on left or right was randomized. Age, sex and sexuality were recorded in a short questionnaire for the European participants and the experimenter noted sex and age for the Hadza. Randomization for the Europeans was done using computer-generated random numbers, whereas for the Hadza this was done via the experimenter shuffling the image pairs and dealing left and right images at random.

Additional data were collected on Hadza women's perceptions of the male judges. Pictures of all possible pairs of men within a given camp were shown to all women living within the same camp in order to get within-camp ranks of all men. Women were asked to make forced choice decisions about the men based on best hunter, most attractive in appearance, best father, most healthy and who spends the most time with their children. The pictures were displayed on a computer and both the pairing order and the presentation of the actual pictures (e.g. whether they were displayed on the left or right side of the computer screen) were randomized. One set of rankings for a particular measure was collected before moving on to a new set. For instance, women were first asked to make a forced choice for ‘best hunter’ for all possible pairs of men in each camp before being asked to choose the most attractive man from each pair. This methodology helps ensure some independence between the questions. Ranks were averaged across all women in a camp and since some camps were bigger than the others, men's within-camp ranks were standardized by transforming them to z-scores to allow for comparisons across camps. Cronbach's alpha was calculated suggesting that the agreement was high for ranking of all traits. Alpha ranged from 0.686 to 0.969 (mean=0.873) for the three camps. The third camp was the smallest and we did not compute agreement for best father or time spent with children owing to the small sample size of men with children (n=3). Data are missing for four men because they were tested outside the three main camps and no ranking data was collected. Data are missing for an extra four men for best father and time spent with children due to these men not having children.

3. Results

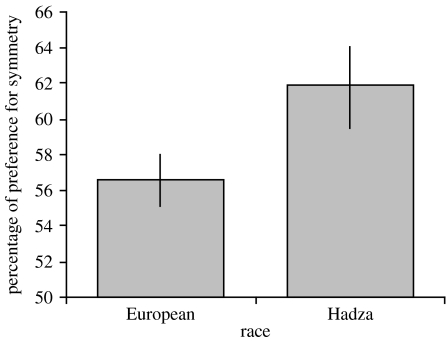

We computed symmetry preference as the number of symmetric faces chosen converted to a percentage score (100%=all symmetric faces chosen). This was computed separately for European and Hadza faces. A repeated measures ANOVA was conducted with ‘face-race’ (European/Hadza) as a within participant factor and ‘rater-race’ (European/Hadza) and ‘rater-sex’ (male/female) as between participant factors. This revealed a significant main effect of rater-race (F1,116=4.05, p=0.046). No other effects of interactions were significant (all F1,116<0.46, p>0.498). From figure 2, it can be seen that Hadza judges had stronger preferences for symmetry than European judges. One sample t-test comparing preferences for symmetry, collapsing across both sex of judge and race of faces, against chance (50%) revealed significant preferences for symmetry in both the UK (mean=56.5, s.d.=12.8, t77=4.52, p<0.001, Cohen's D=1.03) and Hadza (mean=61.9, s.d.=15.7, t41=4.93, p<0.001, Cohen's D=1.54) samples.

Figure 2.

Percentage of preferences for symmetry (±1 s.e. of mean) in opposite-sex faces split by European (N=78) and Hadza (N=42) judges.

To examine variability in preference, a composite symmetry preference score was calculated by taking the average score for both European and Hadza faces. Note that sample size differs in these calculations as complete data were unable to be collected for all participants, Pearson product moment correlations were performed for several traits relevant to male quality and symmetry preferences. These correlations revealed a significant positive correlation between a man's perceived hunting ability (N=17, r=0.544, p=0.024) and their preferences for symmetry in female faces and a close to significant correlation between perceived attractiveness (N=17, r=0.466, p=0.096) and preference for symmetry. Correlations did not reach significance between health (N=17, r=0.041, p=0.877), good father (N=13, r=0.290, p=0.336) and time spent with children (N=13, r=0.284, p=0.346) and preferences for symmetry. We found no significant correlations between symmetry preference and male age (N=21, r=−0.274, p=0.277).

For female Hadza participants, we examined relationships relevant to reproduction. With a composite symmetry preference score, we found no significant correlations between symmetry preference and female age (r=0.159, p=0.492). We selected Hadza women below 41 years of age to restrict the sample to reproductively active women. Small sample sizes meant we did not calculate statistics comparing married with unmarried (N=2) women. Three women reported to be pregnant and six women were nursing and so we compared the preferences of those pregnant/nursing (N=9) with those who were not either (N=9) in a repeated measures ANOVA with race of face (European/Hadza) as a within-participant variable and pregnant/nursing (yes/no) as a between-participant variable. There was a close to significant interaction between pregnant/nursing and race of faces so that those women who were pregnant/nursing preferred symmetry more than those who were not when judging Hadza faces (F1,17=4.34, p=0.053). No other effects or interactions were close to significance (F1,17<0.45, p>0.510). Independent sample t-tests revealed that preferences were close to being significantly higher for those who were pregnant/nursing than those who were not for Hadza faces (yes mean=68.9, s.d.=10.5, no mean=54.0, s.d.=21.2, t17=−1.90, p=0.074, Cohen's D=0.90) but not for European faces (yes mean=60.0.0, s.d.=17.3, no mean=68.0, s.d.=14.0, t17=1.11, p=0.281, Cohen's D=0.52).

4. Discussion

The current study demonstrates both similarities and differences in face preferences between Hadza and UK judges. Men and women judged opposite-sex faces, and symmetry was preferred to asymmetry in all faces across male and female faces and across UK and Hadza faces. Our study is the first to show that facial symmetry is attractive in a relatively isolated hunter-gatherer population. There was also a significant difference between UK and Hadza judges in terms of the overall preference with Hadza judges more strongly preferring symmetry in the faces. The methods did differ in assessing preferences between the two groups with one group taking the test face to face and the other taking the test on computer screen. There is, however, no strong reason to believe that participant's choices or motivations would differ based on the manner in which the test was carried out.

Both cultures preferred symmetry indicating cross-cultural agreement that symmetry is attractive as has been seen in prior studies in a Japanese sample (Rhodes et al. 2001). Such data are important as they suggest that preferences for symmetry are not arbitrary across cultures, which further highlights the importance of symmetrical appearance as an attractive trait in humans, just as it is in other species (Møller 1992; Waitt & Little 2006). Symmetry has been proposed to be attractive owing to experience with faces (Enquist & Arak 1994). The Hadza, however, showed no difference in their preference between European and Hadza faces even though they have limited experience with European faces. We have previously found that Hadza judges do not prefer more average European faces but do prefer more average Hadza faces (Apicella et al. in press). If limited visual experience leads to a lack of preference for averageness in European faces then comparison with an average is unlikely to account for preferences for symmetry in European faces among the Hadza. Such a logic also suggests that different visual experience does not account for the increased preferences for symmetry in the Hadza.

Differences in preferences may instead reflect an adaptive response to particular environmental or cultural variables. Given symmetry is proposed to advertise immunocompetence in both males and females (Thornhill & Gangestad 1999), the pathogen prevalence explanation is plausible to explain the increased preference for symmetry in the Hadza judges. Penton-Voak et al. (2004) found stronger preferences for masculinity in Jamaicans than in the UK and Japan and suggested that a higher pathogen prevalence may result in increased preferences for masculinity in male faces as it has been shown that pathogen load is positively related to the importance of facial attractiveness in mate choice across different cultures (Gangestad & Buss 1993) and that masculinity is more preferred under conditions where women may acquire genetic benefits to offspring (Penton-Voak et al. 1999; Little et al. 2002). As individuals close to the equator have higher pathogen loads (Low 1990) and outdoor living may increase exposure to pathogens, a difference in pathogen load between our samples may also explain increased preferences for symmetry in the Hadza. Penton-Voak et al. (2004) also suggest differences in culture could also lead to adaptive preferences. For example, societal tendencies towards relatively low paternal investment or emphasis on physical quality may increase the importance of proposed signs of immunocompetence like symmetry. More data examining symmetry preferences across culture will be important to determine the exact conditions under which symmetry is more or less preferred.

As well as variability between cultures, we also assessed variability in symmetry preferences among the Hadza. We found that men who were perceived as better hunters and as more attractive showed the strongest preferences for symmetry in female faces. This finding is analogous to findings that women who think they are attractive are choosier about face traits (Little et al. 2001; Little & Mannion 2006) and findings in other species whereby high quality males are also choosier in their partner preferences. We note that the Hadza women knew the men that they were rating and so attractiveness, while focused on physical traits, may reflect a general attraction.

Jones et al. (2005) have shown that women who are pregnant have higher preferences for health in faces and decreased preferences for masculinity. While we examined preferences for Hadza women who were pregnant and/or nursing, the logic remains similar though potentially the hormonal profiles differ. Women who are pregnant/nursing have the greatest need of investment in their offspring and a greater motivation to avoid disease. That those pregnant or nursing had strongest preferences for symmetry (though only when judging Hadza faces) fits well with the later proposal if symmetric men are more resistant to disease. Alternatively, if more symmetrical men tend to be better hunters, women could be attracted to them for their provisioning potential. Provisioning is important among foragers as male contribution to diet is positively correlated with female reproductive success (Marlowe 2001). The individual differences shown here then are in line with the pattern seen in Western cultures for facial masculinity preferences. Such differences highlight strategic elements of symmetry preferences but we note that the small sample sizes here limit the conclusions that can be drawn.

In summary, the current study demonstrates that symmetry is more strongly preferred in a hunter-gatherer society than in the UK, although symmetry was found attractive in both the cultures. The different ecological conditions and cultures may play a role in generating such differences. In the same way that some individual differences in preferences have been theorized to be adaptive, so cultural variation in preference should be adaptive if it reflects adaptation to local conditions. Symmetry can be seen as an attractive trait across cultures, but cultures, and individuals within those cultures, may also vary in their symmetry preference in an adaptive fashion. In this way, individual and cultural differences in preferences can themselves be the outcome of a universal adaptation.

Acknowledgments

A.C.L. is supported by a Royal Society University Research Fellowship. F. W. M. is sponsored by the National Science Foundation grant no. 0544751. Monetary support for this work was also provided by the Biological Anthropology Department of Harvard University. We thank COSTECH for having permitted us to conduct research in Tanzania, and the UK sample and the Hadza for their participation.

References

- Apicella, C. L., Little, A. C. & Marlowe, F. W. In press. Facial averageness and attractiveness in an isolated population of hunter-gatherers. Perception [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cunningham M.R, Roberts A.R, Barbee A.P, Druen P.B. “Their ideas of beauty are, on the whole, the same as ours”: consistency and variability in the cross-cultural perception of female attractiveness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995;68:261–279. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.68.2.261 [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. John Murray; London: 1871. [Google Scholar]

- Enquist M, Arak A. Symmetry, beauty and evolution. Nature. 1994;372:169–172. doi: 10.1038/372169a0. doi:10.1038/372169a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C.S, Beach F.A. Harper & Row; New York, NY: 1951. Patterns of sexual behaviour. [Google Scholar]

- Gangestad S.W, Buss D.M. Pathogen prevalence and human mate preferences. Ethol. Sociobiol. 1993;14:89–96. doi:10.1016/0162-3095(93)90009-7 [Google Scholar]

- Gangestad S.W, Simpson J.A. The evolution of human mating: trade-offs and strategic pluralism. Behav. Brain Sci. 2000;23:573–644. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x0000337x. doi:10.1017/S0140525X0000337X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray P.B, Marlowe F. Fluctuating asymmetry of a foraging population: the Hadza of Tanzania. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2002;29:495–501. doi: 10.1080/03014460110112060. doi:10.1080/03014460110112060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B.C, et al. Menstrual cycle, pregnancy and oral contraceptive use alter attraction to apparent health in faces. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2005;272:347–354. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2962. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowner R. Facial asymmetry and attractiveness judgment in developmental perspective. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 1996;22:662–675. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.22.3.662. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.22.3.662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois J.H, Kalakanis L, Rubenstein A.J, Larson A, Hallamm M, Smoot M. Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol. Bull. 2000;126:390–423. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.390. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little A.C, Jones B.C. Evidence against perceptual bias views for symmetry preferences in human faces. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2003;270:1759–1763. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2445. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little A.C, Mannion H. Viewing attractive or unattractive same-sex individuals changes self-rated attractiveness and face preferences in women. Anim. Behav. 2006;72:981–987. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.01.026 [Google Scholar]

- Little A.C, Burt D.M, Penton-Voak I.S, Perrett D.I. Self-perceived attractiveness influences human female preferences for sexual dimorphism and symmetry in male faces. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2001;268:39–44. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1327. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little A.C, Jones B.C, Penton-Voak I.S, Burt D.M, Perrett D.I. Partnership status and the temporal context of relationships influence human female preferences for sexual dimorphism in male face shape. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2002;269:1095–1100. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.1984. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low B.S. Marriage systems and pathogen stress in human societies. Am. Zool. 1990;30:325–339. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe F. Male contribution to diet and female reproductive success among foragers. Curr. Anthropol. 2001;42:755–760. doi:10.1086/323820 [Google Scholar]

- Møller A.P. Fluctuating asymmetry in male sexual ornaments may reliably reveal male quality. Anim. Behav. 1990;40:1185–1187. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80187-3 [Google Scholar]

- Møller A.P. Female swallow preference for symmetrical male sexual ornaments. Nature. 1992;357:238–240. doi: 10.1038/357238a0. doi:10.1038/357238a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller A.P. Developmental stability and fitness: a review. Am. Nat. 1997;149:916–942. doi: 10.1086/286030. doi:10.1086/286030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penton-Voak I.S, Perrett D.I, Castles D.L, Kobayashi T, Burt D.M, Murray L.K, Minamisawa R. Menstrual cycle alters face preference. Nature. 1999;399:741–742. doi: 10.1038/21557. doi:10.1038/21557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penton-Voak I.S, Jones B.C, Little A.C, Baker S, Tiddeman B, Burt D.M, Perrett D.I. Symmetry, sexual dimorphism in facial proportions, and male facial attractiveness. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2001;268:1617–1623. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1703. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penton-Voak I.S, Jacobson A, Trivers R. Populational differences in attractiveness judgements of male and female faces: comparing British and Jamaican samples. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2004;25:355–370. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2004.06.002 [Google Scholar]

- Perrett D.I, Burt D.M, Penton-Voak I.S, Lee K.J, Rowland D.A, Edwards R. Symmetry and human facial attractiveness. Evol. Hum. Behav. 1999;20:295–307. doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(99)00014-8 [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes G, Yoshikawa S, Clark A, Lee K, McKay R, Akamatsu S. Attractiveness of facial averageness and symmetry in non-Western populations: in search of biologically based standards of beauty. Perception. 2001;30:611–625. doi: 10.1068/p3123. doi:10.1068/p3123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheib J.E, Gangestad S.W, Thornhill R. Facial attractiveness, symmetry, and cues to good genes. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1999;266:1913–1917. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0866. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill R, Gangestad S.W. Facial attractiveness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 1999;3:452–460. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(99)01403-5. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(99)01403-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill R, Gangestad S.W. Facial sexual dimorphism, developmental stability, and susceptibility to disease in men and women. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2006;27:131–144. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.06.001 [Google Scholar]

- Valen L.V. A study of fluctuating asymmetry. Evolution. 1962;16:125–142. doi:10.2307/2406192 [Google Scholar]

- Waitt C, Little A.C. Preferences for symmetry in conspecific facial shape among Macaca mulatta. Int. J. Primatol. 2006;27:133–145. doi:10.1007/s10764-005-9015-y [Google Scholar]