Abstract

The semiempirical PM3 method, calibrated against ab initio HF/6–31+G(d) theory, has been used to elucidate the reaction of 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE) with the carboxylate of Asp-124 at the active site of haloalkane dehalogenase of Xanthobacter autothropicus. Asp-124 and 13 other amino acid side chains that make up the active site cavity (Glu-56, Trp-125, Phe-128, Phe-172, Trp-175, Leu-179, Val-219, Phe-222, Pro-223, Val-226, Leu-262, Leu-263, and His-289) were included in the calculations. The three most significant observations of the present study are that: (i) the DCE substrate and Asp-124 carboxylate, in the reactive ES complex, are present as an ion-molecule complex with a structure similar to that seen in the gas-phase reaction of AcO− with DCE; (ii) the structures of the transition states in the gas-phase and enzymatic reaction are much the same where the structure formed at the active site is somewhat exploded; and (iii) the enthalpies in going from ground states to transition states in the enzymatic and gas-phase reactions differ by only a couple kcal/mol. The dehalogenase derives its catalytic power from: (i) bringing the electrophile and nucleophile together in a low-dielectric environment in an orientation that allows the reaction to occur without much structural reorganization; (ii) desolvation; and (iii) stabilizing the leaving chloride anion by Trp-125 and Trp-175 through hydrogen bonding.

For a catalytic reaction, knowledge of the structure of the critical transition state (TS) tells much about the means of catalysis. This is particularly so in the case of enzyme catalysis, considering the school of thought that enzyme catalysis is due to transition-state stabilization (1–4). Even though experimental techniques such as x-ray diffraction and NMR have provided and will continue to provide valuable structural information concerning the enzyme–substrate (ES), enzyme–intermediate, and enzyme–product complexes, it is highly unlikely that experimental techniques will ever allow direct observation of the transition state in an enzymatic reaction because of the extremely short life time of the transition state.

An approach to characterizing a TS at the active site of an enzyme is to use quantum mechanical theory (5–7). To test this procedure, the following criteria must be met. First, for the theoretical results to be meaningful, the method should be able to treat at least the amino acid residues that line the active site of the enzyme. Second, the enzyme and the substrate must be small in size. Third, for the sake of simplicity, the reaction being studied should consist of a single step, thereby obviating intermediates. Fourth, a well studied enzyme must be chosen so that the theoretical results can be validated. The catalytic reactions with the haloalkane dehalogenase of Xanthobacter autothropicus meet these criteria (8).

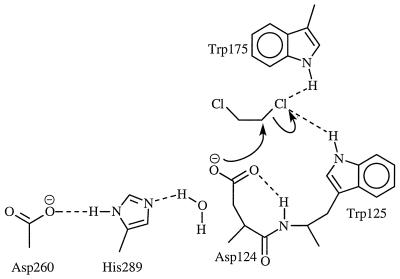

Dehalogenation enzymes have attracted considerable attention owning to the potential of applying these enzymes to the treatment of halogenated hydrocarbon-contaminated soil and water supplies (9–11). Haloalkane dehalogenase is of particular interest because it catalyzes hydrolysis of alkyl halides without requiring any cofactors or metal ions (8). The enzymatic hydrolysis of alkyl halides to the corresponding alcohols follows a two-step process, which involves the formation of an alkyl-enzyme ester intermediate (12–14). Our interest is in the initial step of the enzymatic-dehalogenation reaction, which involves a nucleophilic attack of the carboxylate group of Asp-124 on the halogen-bearing carbon, displacing the chloride via an SN2-displacement reaction (Scheme1). From examination of the x-ray crystallographic structure of the ES complex, Verschueren et al. (12–14) observed the indole NH groups of Trp-125 and Trp-175 to be in position to hydrogen bond to the leaving chloride and proposed this to be assisting in departure of Cl− from the haloalkane. This feature has since been confirmed by other experimental studies (15). The simplicity of the bimolecular SN2 displacement of Cl− from a primary haloalkane by a carboxylate anion allows the comparison of the transition states for such a displacement in non-enzymatic and enzymatic reactions. Using ab initio and semiempirical molecular orbital theory, the non-enzymatic reaction of Eq. 1 has recently been studied in both gas phase and in solution in this laboratory (16). Here we report the results of an investigation of the enzymatic reaction.

|

1 |

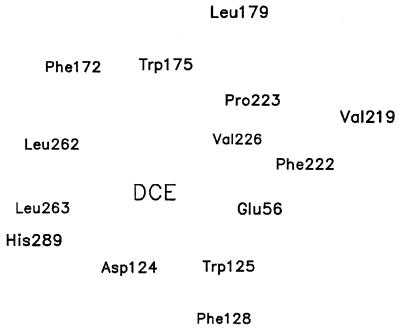

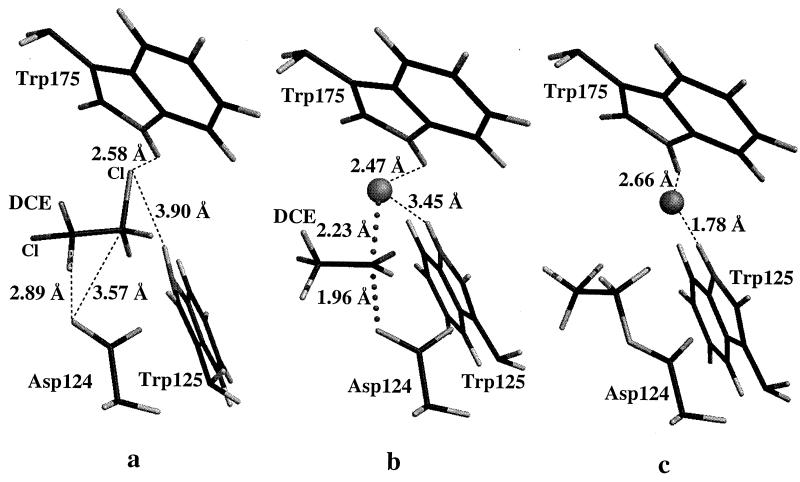

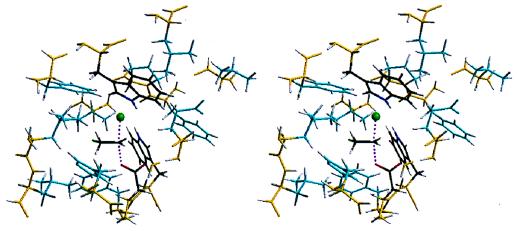

Currently, it is computationally prohibitive to include an entire enzyme in a quantum mechanical computation. In the present study, the active site model consists of a crystallographic water and the 14 amino acid residues (Glu-56, Asp-124, Trp-125, Phe-128, Phe-172, Trp-175, Leu-179, Val-219, Phe-222, Pro-223, Val-226, Leu-262, Leu-263, and His-289; see Fig. 1) that surround the Asp-124 carboxylate anion nucleophile and the 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE) substrate. Additional hydrogen atoms were included to satisfy all valences of the crystal structure coordinates; the resulting system of partial amino acid structures and substrate contains 288 atoms. To retain the overall structure of the system during the calculations, the peptide backbone atoms were held fixed to their x-ray crystallographic coordinates (2dhc) to compensate for the absence of the rest of the enzyme. All side chain atoms and DCE were allowed to move. The PM3 (17) hamiltonian as implemented in gaussian 94 (18) was used. PM3 was chosen based on the following observations. Our previous study (16) has demonstrated that the semiempirical PM3 method provides essentially the same transition-state structure for the reaction of Eq. 1 as does ab initio HF/6–31+G(d) level of theory. The semiempirical PM3 was chosen over AM1 (19) for comparison with ab initio calculations because AM1 tends to give bifurcated hydrogen bonding geometries (20). Also, the large error associated with AM1-calculated heat of formation of chloride ion (21) further limits its utility for our purpose. To determine the entire reaction path of the substitution reaction, we calculated the structures of the following species: (1) the active site cavity modeled by the 14 residues and one water molecule; (2) the active site containing 1,2-dichloroethane substrate (Fig. 2a); (3) the active site with the SN2 TS (Figs. 2b and 3); and (4) the alkyl-enzyme ester product and leaving Cl− that is held between the NH groups of Trp-125 and Trp-175 (Fig. 2c). In all calculations, the Asp-124 is assumed to be ionized because the x-ray crystallographic studies indicate that Asp-124 is ionized in the presence of the DCE substrate.

Figure 1.

The 14 amino acids that were included in the calculations. The relative position of each residue is projected from the x-ray crystal structure.

Figure 2.

The three PM3-calculated stationary points for the chloride displacement from DCE by the carboxylate of Asp-124 in the active site of haloalkane dehalogenase. Only the amino acid residue side chains involved in the SN2 displacement and the substrate are shown. (A) The ES complex, where the nucleophilic oxygen is 3.57 Å from the electrophilic carbon. (B) The transition state. (C) The ester intermediate with the bound chloride between the indole HN of Trp-125 and Trp-175.

Figure 3.

A stereoview of the PM3-calculated transition state active site with 14 amino acid residues surrounding the 1,2-dichloroethane substrate. This view of the active site is from within the enzyme, and the active site is completely sequestered from solvent. The partial bonds of the SN2 reaction are colored in magenta. Yellow-colored atoms of the peptide backbone are those fixed during the calculation. Those amino acid residue side chains that were allowed to move during the calculation are colored cyan. The amino acid residues involved in the reaction (Asp-124, Trp-125, and Trp-175) and the substrate are color-coded in the CPK standard: C, black; O, red; N, dark blue; H, white; and Cl, green.

In the x-ray crystallographic structure of haloalkane dehalogenase with bound 1,2-dichloroethane substrate (12–14), the attacking oxygen of the side chain carboxylate of Asp-124 is located approximately equidistant to the two carbon atoms of DCE (3.5 and 3.5 Å, as reported in the Protein Data Bank file). In the PM3-calculated structure of the active site containing DCE substrate (2), the attacking carboxylate oxygen is 3.6 Å away from the DCE carbon undergoing reaction and 2.9 Å away from the adjacent carbon as shown in Fig. 2a. The difference between the calculated and the x-ray distances is probably due to the PM3 geometry corresponding to a single energy minimum, whereas the x-ray crystal structure is a time-averaged structure. The calculated ground state is very similar to the gas-phase ion–molecule complex for the non-enzymatic reaction (Eq. 1) of DCE with acetate (16). It should be noted that in 2, DCE is in a gauche-like conformation with a Cl-C-C-Cl dihedral angle of 74.2°, which also is similar to the dihedral angle in the gas-phase ion–molecule complex (16). In the original x-ray crystallographic study, DCE was built into the enzyme active site in a trans conformation during structure refinement, although the electron density for one of the chlorines is not very strong (12–14). However, as indicated by our previous ab initio calculations on the non-enzymatic reaction of AcO− with DCE and the current calculations in the active site, DCE is probably in a gauche conformation or a mixture of both trans and gauche when bound in the active site of the enzyme. The gauche form is expected to have a stronger interaction with the enzyme than the trans form because the former has a dipole. If DCE is in the trans form on approach to the carboxylate of Asp-124, there will be a large repulsion between the negatively charged carboxylate group and the chlorine on the adjacent carbon of DCE. This repulsion gets stronger as DCE gets closer to the carboxylate; a simple conformational change (trans to gauche) alleviates this unfavorable interaction. Thus, the active form of DCE is the gauche conformation.

To locate a transition state, a stepwise procedure was followed. First, the gas-phase transition state was docked into the active site by superimposing the -CH2-COO- moiety of the gas-phase transition state and the side chain carboxylate of Asp-124. The transition state was optimized with the amino acid side chains (including the crystallographic water) in a fixed state. Second, with the resulting transition state fixed, the amino acid side chains were optimized. Third, the transition state was optimized again with the optimized side chains fixed. Lastly, both side chains and transition state were optimized together. Starting with the gas-phase transition state rather than the substrate ground state greatly simplifies the transition-state search and shortens the computational time. The same transition state is ensured when starting with substrate ground state.

The PM3-calculated transition state inside the model cavity (3; Figs. 2b and 3) is similar to the PM3-calculated gas-phase transition state for reaction of AcO− with DCE (16). The C · · · O distance of the forming ester bond is 1.965 Å in 3, and the corresponding C · · · O distance in the transition state of the gas-phase reaction is 1.942 Å. Similarly, the C · · · Cl distance is 2.228 Å in 3, whereas the corresponding distance is 2.196 Å for the non-enzymatic reaction in the gas phase. Clearly, the transition state in the active site is slightly looser than the transition state for the non-enzymatic reaction in the gas phase. This is in agreement with previous theoretical observations that the transition state of SN2 reactions seems to be implastic (16, 22). In addition, the orientation of the remaining chlorine atom of DCE in the transition state is also similar. The Cl-C-C-Cl dihedral angle in the transition state of 3 is 67.4°, and it is 92.9° in the PM3-calculated gas-phase transition state of the non-enzymatic reaction. In the transition state of 3, the two NH · · · Cl distances are 2.47 Å (to Trp-175) and 3.48 Å (to Trp-125), and the corresponding N · · · Cl distances are 3.1 and 4.2 Å, respectively. To check whether the unequal N · · · Cl distances were caused by the constraints imposed during the PM3 calculations, we reconstituted the calculated E⋅TS into the enzyme and carried out molecular mechanics optimization on the entire enzyme with bound crystallographic water molecules using quanta/charmm (Micron Separations). During the molecular mechanical calculation, the forming O · · · C and the breaking C · · · Cl distances were kept fixed and no other constraints were used. However, after several hundred steps of energy minimization we did not observe any indication that the two N · · · Cl distances become equal. Further molecular dynamics simulations will be carried out to examine this aspect of the reaction.

Surprisingly, in the calculated ester product of the SN2 reaction (4; Fig. 2c), the -OCH2CH2Cl group is in an almost eclipsed conformation as expressed by Cl-C-C-O dihedral angle of −114.6°. This might be due to the fact that the model cavity has limited flexibility because of the fixed backbone atoms. The chloride anion product has moved between the two tryptophan indole NH hydrogens. However, the chloride ion is much closer to the indole nitrogen atom of the Trp-125 residue. In the product, the Cl · · · N distances are 3.54 Å (to the indole nitrogen of Trp-175) and 2.82 Å (to the indole nitrogen of Trp-125) compared with the x-ray coordinate distances of 3.2 and 3.5 Å, respectively. The Cl · · · H-(N) distances are 2.48 (to Trp-175) and 1.75 Å (to Trp-125), respectively. Again, molecular dynamics simulations with the entire enzyme–product complex could provide more information on the hydrogen-bonding interactions between the chloride ion and the two indole HN hydrogens.

We also tried to estimate the potential energy barrier for the SN2 reaction in the active site. However, it should be pointed out that these energetic calculations may only be approximations due to the restriction of the movement of the peptide backbone in the energy-minimization calculations. A recent study on carbonic anhydrase II indicated that the dynamic motion of the enzyme has a large effect on the calculated energetics (23). The calculated energies reveal a complexation energy of −15.4 kcal/mol for the formation of the ES complex (1 + DCE → 2). DCE is not well solvated in aqueous solution, and the experimental solvation free energy for DCE is only about −1.5 kcal/mol (24). Therefore, it requires only approximately 1.5 kcal/mol free energy to bring DCE to the active site of the enzyme. However, there is a large entropic penalty for the formation of the ES complex. The entropic cost of 3–6 kcal/mol (TΔS) to bring DCE to the active site can be estimated roughly from experimental entropies in solution for formation of complexes and in comparison of reactions of different kinetic order at 25°C (25). Thus, there is at least a 4.5–7.5 kcal/mol free energy cost to bring DCE to the active site. However, the binding energy gained is enough to compensate for this free energy cost. As a result, the free energy of formation of the ES complex is probably less negative than the above-mentioned value (−15.4 kcal/mol) by at least 4.5–7.5 kcal/mol. The overall reaction is exothermic by 13.6 kcal/mol, and the overall potential energy barrier is about 17 kcal/mol. Remembering that the relationship of Asp-124–CO2− and DCE is that of a gas-phase ion–molecule complex, it is interesting to note that the barrier (32.5 kcal/mol) from the ES complex to the enzyme-bound TS (2 → 3) and the barrier from the ion–molecule complex to the same transition state in the gas-phase nonenzymatic reaction (16) differ only by about 2 kcal/mol. Our previous study indicated that the calculated gas-phase non-enzymatic reaction barrier using PM3 is about 7.3 kcal/mol higher than the corresponding barrier calculated using ab initio molecular orbital theory at the HF/6–31+G(d) level (16). Thus, the PM3 barrier for the enzymatic reaction should be corrected by subtraction of ≈7.3 kcal/mol to provide ≈25 kcal/mol.

In the enzyme–substrate complex, the relative arrangement of DCE to the carboxylate of Asp-124 resembles the gas-phase ion–molecule complex of the non-enzymatic reaction. Weak hydrogen bonding interactions between one of the DCE chlorines and the indole NHs of Trp-125 and Trp-175 along with the ion–molecule complex electrostatic attraction hold the substrate in place. As the SN2 reaction proceeds, negative charge gradually accumulates on the leaving chlorine, strengthening hydrogen-bonding interactions between Clδ− and the indole HNs. This differential hydrogen bonding could provide significant transition-state stabilization (12–14); similar effects have been proposed for other enzymatic reactions (26–30). It has been shown recently that the non-enzymatic reaction is extremely slow in aqueous solution and the gas-phase reaction is very fast (16). Taken together, it is clear that the haloalkane dehalogenase derives its catalytic power from: (i) bringing the electrophile and nucleophile together in a reactive orientation in a very low dielectric environment to allow the reaction to occur without much structural reorganization (16), (ii) stabilizing the chloride anion-leaving group by hydrogen bonding (with the indole NHs of Trp-125 and Trp-175), and (iii) desolvation. Concerning our findings that the enzyme has been selected to provide the most favorable environment for carboxylate nucleophilic attack and to stabilize the gas-phase transition state, we note that Dewar and Storch (31) have previously drawn attention to expected similarities between gas-phase and enzymatic SN2 reactions of negative nucleophile and neutral substrate. They pointed out that such enzymatic reactions, like the gas-phase reactions, should pass through reactive ion–molecule complex ground states and that the facility of the enzymatic reaction could be explained by this feature. The SN2 displacement of Cl− in the Xanthobacter autothropicus haloalkane dehalogenase enzyme appears to provide an example. It is well known that ion–molecule SN2 displacements, as in Eq. 1, are much more rapid in the gas phase than in solution (32).

Although our model using 14 residues that form the active site cavity is a reasonable approximation to model the transition-state structure of the enzyme haloalkane dehalogenase-catalyzed reaction, it would be beneficial to investigate how the dynamic motion of the enzyme affects the calculated transition-state structure and the energetics. Further molecular dynamics and combined quantum mechanics and molecular mechanics calculations are underway to address this issue.

Scheme 1.

Acknowledgments

The assistance by Rhonda Torres in using quanta/charmm is appreciated. We acknowledge the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (Urbana, IL) for allocation of computing time. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ES

enzyme substrate

- TS

transition state

- DCE

1,2-dichloroethane

References

- 1.Pauling L. Chem Eng News. 1946;24:1375–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jencks W P. In: Current Aspects of Biochemical Energetics. Kaplan N O, Kennedy E P, editors. New York: Academic; 1966. pp. 273–298. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfenden R. Nature (London) 1969;223:704–705. doi: 10.1038/223704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fersht A R. Enzyme Structure and Mechanism. 2nd Ed. New York: Freeman; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warshel A. Computer Modeling of Chemical Reactions in Enzymes and in Solution. New York: Wiley; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aqvist J, Warshel A. Chem Rev. 1993;93:2523–2544. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daggett V, Schroder S, Kollman P A. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:8926–8935. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keuning S, Janssen D B, Witholt B. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:635–639. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.2.635-639.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fetzner S, Lingens F. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:641–685. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.4.641-685.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janssen D B, van der Ploeg J R, Pries F. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103:29–32. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leisinger T. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1996;7:295–300. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(96)80033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verschueren K H G, Seljee F, Rozeboom H J, Kalk K H, Dijkstra B W. Nature (London) 1993;363:693–698. doi: 10.1038/363693a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verschueren K H G, Kingma J, Rozeboom H J, Kalk K H, Janssen D B, Dijkstra B W. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9031–9037. doi: 10.1021/bi00086a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verschueren K H G, Franken S M, Rozeboom H J, Kalk K H, Dijkstra B W. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:856–872. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennes C, Pries F, Krooshof G H, Bokma E, Kingma J, Janssen D B. Eur J Biochem. 1995;228:403–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maulitz A H, Lightstone F C, Zheng Y-J, Bruice T C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6591–6595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart J J P. J Comput Chem. 1989;10:209–220. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frisch M J, Trucks G W, Schlegel H B, Gill P M W, Johnson B G, et al. gaussian 94. Pittsburgh: Gaussian; 1995. , Revision B.2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dewar M J S, Zoebisch E G, Healy E F, Stewart J J P. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:3902–3909. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng Y-J, Merz K M., Jr J Comput Chem. 1992;13:1151–1169. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartsough D, Merz K M., Jr J Phys Chem. 1995;99:11266–11275. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaik S S, Schlegel H B, Wolfe S. Theoretical Aspects of Physical Organic Chemistry: The SN2 Mechanism. New York: Wiley; 1992. pp. 188–191. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merz K M, Jr, Banci L. J Phys Chem. 1996;100:17414–17420. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cabani S, Gianni P, Mollica V, Lepori L. J Solution Chem. 1981;10:563–598. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruice T C. The Enzymes. Vol. 2. New York: Academic; 1970. p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerlt J A, Gassman P G. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11943–11952. doi: 10.1021/bi00096a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng Y-J, Ornstein R L. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:648–655. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng Y -J, Bruice T C. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:3868–3877. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng Y-J, Bruice T C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4285–4288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benning M M, Taylor K L, Liu R-Q, Yang G, Xiang H, Wesenberg G, Dunaway-Mariano D, Holden H M. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8103–8109. doi: 10.1021/bi960768p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dewar M J S, Storch D M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:2225–2229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.8.2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nibbering N M M. Adv Phys Org Chem. 1988;24:1–55. [Google Scholar]