Abstract

Myosin I heavy chain kinase from Acanthamoeba castellanii is activated in vitro by autophosphorylation (8–10 mol of P per mol). The catalytically active C-terminal domain produced by trypsin cleavage of the phosphorylated kinase contains 2–3 mol of P per mol. However, the catalytic domain expressed in a baculovirus–insect cell system is fully active as isolated without autophosphorylation in vitro. We now show that the expressed catalytic domain is inactivated by incubation with acid phosphatase and regains activity upon autophosphorylation. The state of phosphorylation of all of the hydroxyamino acids in the catalytic domain were determined by mass spectrometry of unfractionated protease digests. Ser-627 was phosphorylated in the active, expressed catalytic domain, lost its phosphate when the protein was incubated with phosphatase, and was rephosphorylated when the dephosphorylated protein was incubated with ATP. No other residue was significantly phosphorylated in any of the three samples. Thus, phosphorylation of Ser-627, which is in the same position as the Ser and Thr residues that are phosphorylated in many other kinases, is necessary and sufficient for full activity of the catalytic domain. Ser-627 is also phosphorylated when full-length, native kinase is activated by autophosphorylation.

Myosin I heavy chain kinase (MIHCK) of Acanthamoeba castellanii has been identified as a member of the p21-activated kinase (PAK)/STE20 kinase family based on the sequence of its catalytic domain (1) and, more recently, by the sequence of a putative Cdc42-binding site (H.B., R. Young, and E.D.K., unpublished data). These kinases (PAK65, Ste20p, Cla4, and Shk1), which are activated by autophosphorylation induced by binding to the small GTP-binding proteins, Rac and Cdc42 (but not Rho), are the first enzymes in several kinase cascade signaling pathways through which the small GTPases initiate transcription in the nucleus and cytoskeletal reorganization (for references, see refs. 2 and 3). These small GTPases have not yet been shown to activate Acanthamoeba MIHCK, but Rac and Cdc42 have been shown to stimulate both autophosphorylation and kinase activity (4) of the functionally homologous (5) Dictyostelium MIHCK, whose sequence is also similar to the sequences of PAK and Ste20p (4). The recent reports that PAK/STE20 kinases phosphorylate and activate Acanthamoeba (6) and Dictyostelium (7) myosin I, and have similar specificities for synthetic substrates (6) as Acanthamoeba MIHCK, suggest that the MIHCKs and other PAK/STE20 kinases may have multiple and overlapping functions in vivo. In addition, Rho-associated kinase (8), a member of a different kinase family (2, 3), phosphorylates and regulates the activity of myosin II (9) and myosin II light chain phosphatase (10). Thus, the reorganization of the cytoskeleton induced by Rac, Cdc42, and Rho (11, 12) may, at least in part, result from regulation of myosin phosphorylation and actomyosin activity.

The activity of MIHCK increases about 50-fold coincident with autophosphorylation of up to 8–10 mol of P per mol (13, 14). About 2–3 mol of P per mol are retained in the fully active, ≈35 kDa, C-terminal fragment produced by trypsin digestion of phosphorylated Acanthamoeba MIHCK (15). The catalytic domain could not be obtained by proteolysis of unphosphorylated kinase and, therefore, the activity of the unphosphorylated catalytic domain could not be determined in those experiments. However, the catalytic domain produced by a baculovirus–insect cell expression system is fully active as isolated (1). The present experiments were undertaken to determine whether the expressed MIHCK catalytic domain is fully active without phosphorylation or, as suggested by its resistance to trypsin cleavage (1, 15), was already phosphorylated as expressed and, if the latter, to identify the phosphorylated site(s) essential for catalytic activity. Hopefully, insights into the regulation of Acanthamoeba MIHCK by phosphorylation will be applicable to other members of the PAK/STE20 family of which Acanthamoeba MIHCK is, biochemically, the best characterized member.

We decided to use mass spectrometry of protease digests to identify the phosphorylation site(s) of the expressed catalytic domain because this method does not require use of radioisotopes and, in principle, allows the phosphorylation status of all Ser and Thr residues to be determined in one experiment requiring less than 1 μg of protein. The results presented in this paper illustrate the advantages of mass spectrometry for studies of posttranslational modifications of this kind.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Catalytic Domain of MIHCK.

The catalytic domain of Acanthamoeba MIHCK was expressed as an N-terminal poly(His) (pBlueBacHis vector; Invitrogen) fusion protein in SF9 insect cells, purified by chromatography on a Ni-NTA column (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) and a Mono Q column (Pharmacia Biotech) and stored at −20°C in 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5) containing 50% glycerol (vol/vol), 50 mM KCl, and 1 mM DTT (storage buffer) as described (1). Full-length, native kinase was purified from A. castellanii as described (16). Kinase activity was assayed with synthetic peptide as substrate as described (17).

For dephosphorylation, the catalytic domain and type III potato acid phosphatase (Sigma) were dialyzed separately overnight against 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM mercaptoethanol, 10 mM imidazole (pH 7.0), 1 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and a mixture of protease inhibitors including leupeptin (2.5 μg/ml), soy bean trypsin inhibitor (5 μg/ml), and pepstatin (5 μg/ml). After dialysis, the catalytic domain (0.12–0.18 mg/ml) was incubated with phosphatase (10–12 units/μmol catalytic domain) for 2 h at 30°C in the same buffer, and then mixed with Ni-NTA (1 mg protein/ml of packed resin) equilibrated in the same buffer without the phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and protease inhibitors. The resin was washed with 10 volumes of 10 mM imidazole (pH 7.9) containing 10 mM mercaptoethanol and 500 mM NaCl, followed by 10 volumes of the same buffer containing 50 mM NaCl and then eluted with 4 volumes of 125 mM imidazole (pH 7.0) containing 10 mM mercaptoethanol, 50 mM NaCl, 15% glycerol, and bovine serum albumin (0.2 mg/ml). The concentration of the catalytic domain in the eluates was estimated by scanning Coomassie blue-stained SDS/PAGE gels. In one control, the catalytic domain was incubated without phosphatase and, in another, the kinase and phosphatase were mixed immediately with the Ni-NTA without incubation. The two control samples had the same activity.

Dephosphorylated catalytic domain was autorephosphorylated by incubating for 20 min at 30°C in 50 mM imidazole (pH 7.0) containing 3.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, and 2.5 mM [γ-32P]ATP (300 cpm/pmol). After separation of the protein by SDS/PAGE, the incorporation of 32P was quantified by liquid scintillation counting of the solubilized, excised band (13).

Mass Spectrometry.

A matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI–TOF) mass spectrometer with delayed extraction (Voyager-DE; Perseptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA), a home-built MALDI–ion trap mass spectrometer described previously (18), and an electrospray ion trap mass spectrometer (LCQ; Finnigan–MAT, San Jose, CA) coupled on-line with a microbore HPLC (Magic 2002, Auburn, CA) were used for the identification of the phosphorylation sites of the expressed catalytic domain of MIHCK. For MALDI mass spectrometry (MS), 1 μl of a 2-fold dilution of saturated 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid in acetonitrile/H2O (1:1), the working matrix solution, was mixed with 1 μl of peptide mixture on the sample plate and dried in the air. For on-line HPLC/MS/MS analysis, a C18 column (5 μm particle diameter, 150 A pore size, 0.5 × 150 mm) with mobile phases of acetonitrile/n-propanol/H2O/acetic acid/trifluoroacetic acid in the ratios of 1:1:98:0.1:0.02 (A) and 70:20:10:0.09:0.02 (B) was used with a two-step gradient of 2–60% of B in A in 20 min and 60–98% of B in A in 5 min.

In-solution digestions of the protein (160 ng/digestion) with sequencing grade modified trypsin or endoproteinase Glu-C (Boehringer Mannheim) were carried out for 2 h at 37°C using a protein/enzyme weight ratio of 1:1 in 50 mM NH4HCO3. In-gel trypsin digestions of Cu-stained, SDS/PAGE (Bio-Rad)-separated catalytic domain (200 ng of protein per band) and native MIHCK (1 μg per band) were performed on extensively washed gel slices suspended as fine powders in 10–20 μl of buffer and incubated for 2 h at 37°C using a protein/enzyme weight ratio of 1:1 (J.Q., D. Fenyo, Y. Zhao, W. Zheng, W. W. Hall, D. M. Chao, C. J. Wilson, R. A. Young, and B. T. Chait, unpublished work).

RESULTS

We first tested the possibility that the expressed MIHCK catalytic domain might be constitutively active because of the N-terminal poly(His) fusion peptide that was added to facilitate its purification. As confirmed by SDS/PAGE and N-terminal sequencing, both trypsin (1) and enterokinase (data not shown) removed the N-terminal tag (except for 1 Ser) with no effect on kinase activity.

Effect of Dephosphorylation and Rephosphorylation on Catalytic Activity.

The specific enzymatic activity of the expressed catalytic domain was substantially reduced by phosphatase treatment and returned to its original value when the phosphatase-treated sample was incubated with ATP (Fig. 1). The increase in electrophoretic mobility of the catalytic domain after incubation with phosphatase and its decrease to less than the original value after incubation with ATP (Fig. 1 Inset) provided strong, independent evidence that dephosphorylation and rephosphorylation had, in fact, occurred. Rephosphorylation was quantified by determining the incorporation of 32P from [γ-32P]ATP; about 3.5 mol of P per mol were incorporated into the rephosphorylated catalytic domain. After removal of the poly(His) tag, about half of the 32P (1.8 mol of P per mol) that had been incorporated during rephosphorylation remained with the catalytic domain.

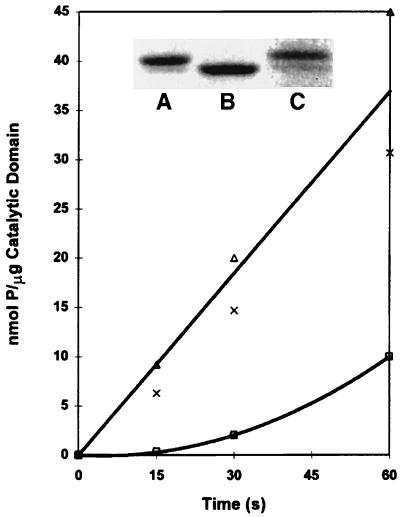

Figure 1.

Effect of dephosphorylation and rephosphorylation on the specific enzymatic activity of expressed MIHCK catalytic domain. Expressed catalytic domain was dephosphorylated and rephosphorylated as described in Materials and Methods. The kinase activities of the original (×), dephosphorylated (□), and rephosphorylated (▵) proteins were assayed using synthetic peptide as substrate. Similar results were obtained in three other experiments. The activity of dephosphorylated catalytic domain increases during the assay because it rapidly autophosphorylates, as observed previously for active proteolytic fragments of MIHCK (19). (Inset) SDS/PAGE of the catalytic domain. Lanes: A, as isolated; B, after dephosphorylation; C, after rephosphorylation. Much less protein was applied to lane C, and its image was photographically enhanced.

Localization of the Phosphopeptide(s) in the Catalytic Domain of MIHCK.

We initially used MALDI–ion trap MS to identify the phosphopeptide(s) produced by in-gel trypsin digestion of Cu-stained, SDS/PAGE-separated catalytic domain. MALDI–ion trap MS is unusual in that a phosphopeptide partially loses the H3PO4 moiety in the mass spectrometer, thereby spontaneously producing a pair of peaks separated by a mass difference of 98 Da (the mass of H3PO4). Thus, a peptide produced by proteolysis can be identified as a phosphopeptide with a high level of confidence (J.Q. and B. T. Chait, unpublished data) if its initial mass is 80 Da (the mass of H3PO4–H2O) greater than the mass calculated from its amino acid sequence and MALDI–ion trap MS shows a second peak of mass 98 Da lower than the initial (18 Da less than the mass from amino acid sequence).

A MALDI–ion trap mass spectrum of the in-gel trypsin digest of the expressed catalytic domain of MIHCK is shown in Fig. 2a. There are two pairs of peaks separated by 98 kDa (Fig. 2a, arrows) indicating that at least one residue of the catalytic domain was phosphorylated during its expression. From the published sequence of the catalytic domain (1) and the measured masses of the peaks, it was determined that the two phosphopeptides came from the same region of the protein. The larger pair¶ was the product of incomplete trypsin digestion with cleavage at K606 and K641: 607ITDFGYGAQLGVGAGQDKRASVVGTTYWMAPEVVK641, with a single phosphate (m/z 3754.7 Da), and the peptide derived from it by the loss of H3PO4 (m/z 3656.2 Da). The masses of the smaller pair identify them as the singly phosphorylated tryptic peptide, 625RASVVGTTYWMAPEVVK641 (m/z 1976.7 Da), produced by cleavage at K624 and K641, and the peptide derived from it by the loss of H3PO4 (m/z 1877.1).

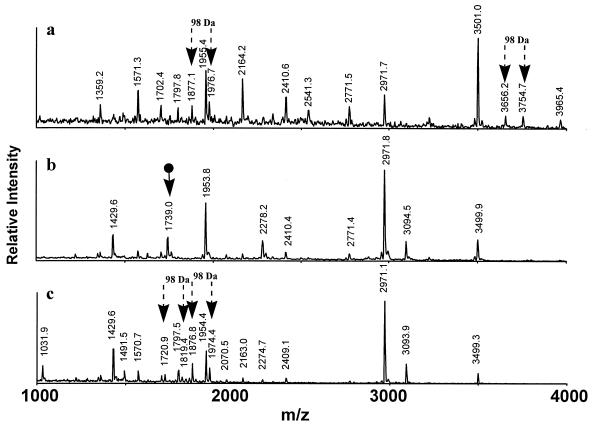

Figure 2.

MALDI–ion trap mass spectra of total trypsin digests of expressed Acanthamoeba MIHCK catalytic domain as isolated (a) and after dephosphorylation (b) and rephosphorylation (c). Arrows in the figure identify peptides of interest (see text). Mass accuracy: ±1 Da (average mass).

Neither pair of peaks was present in the MALDI–ion trap spectrum of the tryptic digest of the dephosphorylated catalytic domain (Fig. 2b), but a new peak appeared with m/z 1739.0 Da (Fig. 2b, arrow), which corresponds to the unphosphorylated sequence 626ASVVGTTYWMAPEVVK641 (cleavage having occurred at R625 rather than at K624). The mass spectrum of the digest of the autorephosphorylated catalytic domain shows two pairs of peaks with a separation of 98 Da (Fig. 2c, arrows) which correspond to singly phosphorylated 625RASVVGTTYWMAPEVVK641 (m/z 1974.4) and singly phosphorylated 626ASVVGTTYWMAPEVVK641 (m/z 1819.4) and the corresponding peptides after loss of H3PO4 (m/z 1876.8 and 1720.9, respectively). The disappearance of the unphosphorylated peptide, m/z 1739.0, upon rephosphorylation (compare Fig. 2c to Fig. 2b) confirmed that the dephosphorylated catalytic domain was rephosphorylated in the same region as was the expressed catalytic domain before it was dephosphorylated.

The results of the MALDI–ion trap mass spectral analysis, coupled with the kinase activity data (Fig. 1), strongly suggested that phosphorylation of either Ser-627, Thr-631, or Thr-632 (or, less likely, any one of them) was required for activation of the catalytic domain. However, as the total number of phosphate moieties in the expressed catalytic domain was not known in these experiments, and as ≈2 mol of P per mol were incorporated when the dephosphorylated catalytic domain was rephosphorylated, it was possible that catalytic activity also correlated with the phosphorylation of a Ser or Thr elsewhere in the molecule. Therefore, we decided to carry out extensive peptide mapping by MALDI–TOF MS of protease digests to determine the phosphorylation status of all 36 Ser and Thr residues in the expressed MIHCK catalytic domain and the 6 Ser and Thr residues in the N-terminal poly(His) tag. In contrast to MALDI–ion trap MS, phosphopeptides are stable in MALDI–TOF MS.

By mass spectrometric analysis of in-solution trypsin and Glu-C digests, peptides accounting for all 42 Ser and Thr residues were identified (Table 1). The N-terminal region of the poly(His) tag was found to be partially phosphorylated (and partially N-acetylated) (Table 1, trypsin peptides containing residues −37 to −15). However, as the poly(His) tag is not part of the catalytic domain and has no effect on its enzymatic activity, this partial phosphorylation could be ignored. The only other phosphorylated peptide (Table 1, trypsin peptide 626–641) was that previously identified by MALDI–ion trap MS; within the sensitivity of the method, this peptide was stoichiometrically phosphorylated as the corresponding unphosphorylated peptide was not observed. Thus, these data established that phosphorylation of either Ser-627, Thr-631, or Thr-632 is both necessary and sufficient for activation of the expressed catalytic domain of MIHCK.

Table 1.

Sequence assignments of peptides observed by MALDI-TOF of trypsin and Glu-C in-solution digestions of expressed MIHCK catalytic domain as purified

| Protease | Residues* | Number of serine + threonine residues | Average mass, Da

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured | Calculated | Difference | |||

| Trypsin | (−37)–(−15) | 3 | 2,565.1 | 2,565.9 | −0.8 |

| Trypsin | (−37)–(−15) + P† | 3 | 2,645.0 | 2,645.9 | −0.9 |

| Trypsin | (−37)–(−15) + P + acetyl‡ | 3 | 2,687.0 | 2,687.9 | −0.9 |

| Trypsin | (−35)–(−2) | 5 | 3,800.5 | 3,801.0 | −0.5 |

| Trypsin | (−1)–457 | 1 | 969.1 | 969.1 | 0.0 |

| Trypsin | 458–490 | 6 | 3,498.2 | 3,498.9 | −0.7 |

| Glu-C | 474–514 | 6 | 4,408.2 | 4,407.2 | +1.0 |

| Glu-C | 515–536 | 2 | 2,626.5 | 2,626.0 | +0.5 |

| Glu-C | 537–553 | 2 | 1,790.5 | 1,789.1 | +0.6 |

| Glu-C | 545–556 | 1 | 1,229.0 | 1,228.4 | +0.6 |

| Glu-C | 557–563 | 1 | 825.2 | 824.0 | +1.2 |

| Glu-C | 564–575 | 2 | 1,304.0 | 1,303.6 | +0.4 |

| Trypsin | 572–583 | 1 | 1,428.1 | 1,428.7 | −0.6 |

| Trypsin | 584–590 | 0 | 861.9 | 862.1 | −0.2 |

| Trypsin | 591–606 | 2 | 1,700.0 | 1,701.1 | −1.1 |

| Trypsin | 607–624§ | 1 | 1,796.1 | 1,797.0 | −0.9 |

| Trypsin | 607–625 | 1 | 1,952.4 | 1,953.1 | −0.7 |

| Trypsin | 626–641§ + P† | 3 | 1,817.0 | 1,818.0 | −1.0 |

| Trypsin | 642–675 | 3 | 3,889.0 | 3,889.6 | −0.6 |

| Trypsin | 676–699 | 2 | 2,645.0 | 2,646.0 | −1.0 |

| Trypsin | 684–704 | 1 | 2,460.9 | 2,461.8 | −0.9 |

| Trypsin | 700–713 | 1 | 1,737.4 | 1,738.0 | −0.6 |

| Trypsin | 714–740 | 6 | 2,969.6 | 2,970.5 | −0.9 |

| Trypsin | 741–753§ | 2 | 1,620.1 | 1,620.8 | −0.7 |

The N-terminal poly(His) tag is numbered (−37) to (−1) and the expressed catalytic domain is residues 451–753 as numbered for the sequence of the full-length kinase.

Phosphopeptides were confirmed by a loss of 80 Da when the sample was treated with phosphatase.

N-terminal acetylation is assumed because the mass is 42 Da higher than calculated for the phosphopeptide.

Sequence confirmed by MS/MS.

Identification of the Phosphorylated Amino Acid.

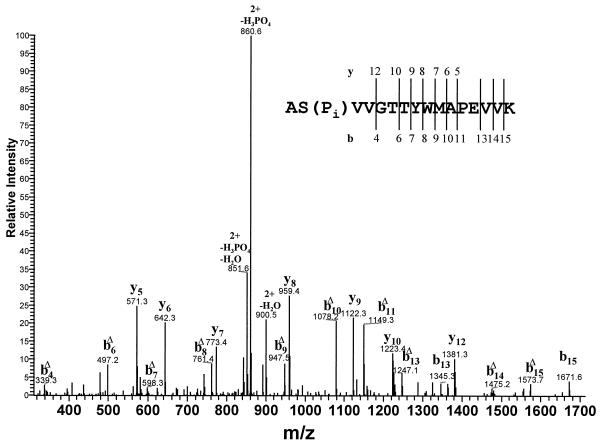

A total trypsin digest of expressed catalytic domain (about 200 ng protein digested in solution) was fractionated on a microbore HPLC connected to an on-line electrospray ion trap mass spectrometer. The experiment was carried out in a data-dependent fashion in which the mass spectrometer switched automatically to the MS/MS mode to record a collision-induced dissociation spectrum once the ion intensity exceeded a preset value as the peptides were eluted from the column. The collision-induced dissociation spectrum of the doubly charged ion of the phosphopeptide with the sequence 626ASVVGTTYWMAPEVVK641, which eluted at ≈40% of mobile phase B, is shown in Fig. 3. The mass of the dominant peak, m/z 860.6, corresponds to the doubly charged phosphopeptide minus H3PO4 (the loss of H3PO4 is expected in ion trap MS/MS), in agreement with the identification of this phosphopeptide by MALDI–ion trap and MALDI–TOF MS (Fig. 2 and Table 1) and confirming that either the Ser or one of the two Thr residues was phosphorylated. The y12 ion at m/z 1381.3 (Fig. 3) produced by collision-induced dissociation corresponds to unphosphorylated 630GTTYWMAPEVVK641, which unequivocally identified Ser-627 as the phosphorylated site. This conclusion was supported by the identification of many other y and b type ions (Fig. 3), especially the series of bnΔ ions with masses consistent with the loss of H3PO4 from phosphoserine-627 (bnΔ ions are produced by the loss of H3PO4 from the corresponding bn ions). Results essentially the same as those in Fig. 3 were also obtained with a sample of MIHCK catalytic domain that had been dephosphorylated with acid phosphatase and then rephosphorylated by incubation with ATP (data not shown). Independent confirmation of Ser-627 as the phosphorylated site was obtained by MALDI–TOF mass measurements during the course of aminopeptidase M digestion of the total tryptic digest of the expressed catalytic domain (data not shown). Thus, Ser-627, and not Thr-631 or Thr-632, is the phosphorylated amino acid that is responsible for the activation of the MIHCK catalytic domain.

Figure 3.

HPLC/MS/MS spectrum of phosphopeptide AS(P)VVGTTYWMAPEVVK. The notations bnΔ denotes the corresponding bn ions minus H3PO4, which serve to confirm the phosphopeptide. Mass accuracy: ±1 Da (monoisotopic mass).

Mass Spectrometry of Tryptic Peptides Produced from Native MIHCK.

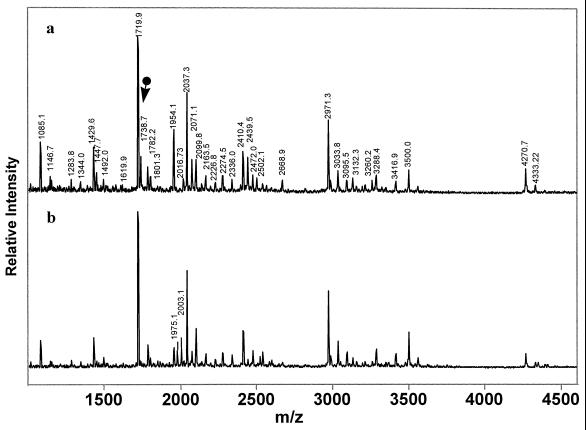

MIHCK purified from the amoeba was subjected to similar analysis before and after its autophosphorylation (Fig. 4). The MALDI–TOF spectrum of in-gel trypsin digests of the isolated, unphosphorylated, inactive MIHCK contained the peak of m/z 1738.7 (Fig. 4a, arrow) corresponding to the unphosphorylated peptide 626ASVVGTTYWMAPEVVK641 observed previously in the dephosphorylated, inactive catalytic domain (Fig. 2a). That peak was not present in the spectrum of autophosphorylated, active MIHCK (Fig. 4b), which contained two new peaks: m/z 1975.1, which corresponds to the singly phosphorylated peptide 625RASVVGTTYWMAPEVVK641, and m/z 2003.1 which corresponds to singly phosphorylated 626ASVVGTTYWMAPEVVKGK643. Although we have not identified the other Ser and Thr residues that are autophosphorylated in native, full-length MIHCK, autophosphorylation of Ser-627 is consistent with the requirement for phosphorylation of this residue for activity of the expressed catalytic domain.

Figure 4.

MALDI–TOF mass spectra of in-gel trypsin digestion of native Acanthamoeba MIHCK before (a) and after (b) autophosphorylation. The marked peak in a corresponds to unphosphorylated peptide 625–641. The labeled peaks in b correspond to the singly phosphorylated peptides 625–641 and 626–643. The unlabeled peaks in b are identical to those labeled in a. Mass accuracy: ±1 Da (average mass).

DISCUSSION

The data in this paper show that phosphorylation of Ser-627, which lies in the activating loop within the linkage region between subdomains VII and VIII (20), is both necessary and sufficient for full activity of the expressed catalytic subdomain of MIHCK. The activities of many other serine/threonine kinases have been shown to be dependent on phosphorylation of Ser or Thr residues at the same or neighboring position(s). These include two other members of the PAK family (Table 2): S6/H4 kinase from human placenta (21) and, as inferred from its activation by substitution of Glu for the putative phosphorylation site (T422E), rat brain α-PAK (22). However, the two corresponding Thr residues of a third member of the PAK/STE20 family, yeast Ste20p (Table 2), can both be replaced by Ala residues in a double mutant (T772A, T773A) with no phenotypic effect in vivo or effect on autophosphorylation in vitro whereas the T777A mutant is inactive in both assays (23). The apparent difference between yeast Ste20p and the three other PAK enzymes deserves further study.

Table 2.

Important serine and threonine residues in the linker region of PAK/STE20 kinases

| Enzyme | Sequence | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| MIHCK | 623KRASVVGTTYWMAPE637 | This paper |

| S6/H4 | 383SSMVGTPYWMAPE395 | 22 |

| α-PAK | 419KRSTMVGTPYWMAPE423 | 23 |

| Ste20p | 770KPTTMVGTPYWMAPE784 | 24 |

Phosphorylation of the underlined residues is required for activity. Phosphorylation of the double underlined residues is presumed to be required for activity based on the effects of amino acid substitutions (see text). The residues in S6/H4 are numbered by analogy to PAK 65 (24).

Although Ser-627 is the only specific residue that must be phosphorylated for full activation of the expressed catalytic domain of Acanthamoeba MIHCK, additional phosphorylations may be necessary for activation of full-length, native kinase (13, 14). It is likely that the native Acanthamoeba MIHCK, as proposed for other PAKs (2), is folded such that its N-terminal region blocks the catalytic domain. The catalytic domain may then be opened to substrate either by the kinase binding to membranes or phospholipid and/or by phospholipid/membrane-stimulated autophosphorylation (13, 14, 25). Consistent with this proposal, autophosphorylation of the 54-kDa C-terminal fragment of native kinase (19) and of the expressed catalytic domain (data not shown) are much faster than autophosphorylation of native kinase. This explanation would also be consistent with the need for phosphorylation of a second residue in the catalytic region of S6/H4 kinase prepared from the holoenzyme (21), which has a substantial extension N terminal to the catalytic domain, and for activation by autophosphorylation in vitro of kinases such as Rho-activated protein kinase N (26), in which the residue corresponding to MIHCK Ser-627 seems to be constitutively phosphorylated.

In addition to the specific information provided on the regulation of Acanthamoeba MIHCK by autophosphorylation, the data in this paper more generally illustrate the power of applying mass spectrometric analysis to problems of this kind. One can obtain information on the phosphorylation state of many residues throughout an entire protein in a single analysis that requires very little material that need not be highly purified; as demonstrated here, microgram quantities of protein separated by SDS/PAGE are sufficient for a full analysis that would be impossible to obtain as readily by any other means.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Brian Martin for N-terminal sequencing.

ABBREVIATIONS

- MALDI

matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization

- MIHCK

myosin I heavy chain kinase

- MS

mass spectrometry

- TOF

time-of-flight

- PAK

p21-activated kinase

Footnotes

References

- 1.Brzeska H, Szczepanowska J, Hoey J, Korn E D. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27056–27062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.27056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim L, Manser E, Leung T, Hall C. Eur J Biochem. 1996;242:171–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0171r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyriakis J M, Avruch J. BioEssays. 1996;18:567–577. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee S-F, Egelhoff T T, Mahasneh A, Côté G P. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27044–27048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.27044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S-F, Côté G P. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11776–11782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brzeska H, Knaus U G, Wang Z-Y, Bokoch G M, Korn E D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1092–1095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu C, Lee S-F, Furmaniak-Kazimierczak, Côté G P, Thomas D Y, Leberer E. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31787–31790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsui T, Amano M, Yamamoto T, Chihara K, Nakafuku M, Ito M, Nakano T, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K. EMBO J. 1996;15:2208–2216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amano M, Ito M, Kimura K, Fukata T, Chihara K, Nakano T, Matsuura Y, Kaibuchi K. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20246–20249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimura K, Ito M, Amano M, Chihara K, Fukata Y, Nakafuku M, Yamamori B, Feng J H, Nakano T, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K. Science. 1996;273:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sells M A, Knaus U G, Bagrodia S, Ambrose D M, Bokoch G M, Chernoff J. Curr Biol. 1997;7:202–210. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(97)70091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amano M, Chihara K, Kimura K, Fukata Y, Nakamura N, Matsuura Y, Kaibuchi K. Science. 1997;275:1308–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brzeska H, Lynch T J, Korn E D. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:3591–3594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Z Y, Brzeska H, Baines I C, Korn E D. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27969–27976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brzeska H, Martin B M, Korn E D. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27049–27055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.27049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynch T J, Brzeska H, Baines I C, Korn E D. Methods Enzymol. 1990;196:12–23. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)96004-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brzeska H, Lynch T J, Martin B, Corigliano-Murphy A, Korn E D. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:109–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin J, Steenvoorden R J J M, Chait B T. Anal Chem. 1996;68:1784–1791. doi: 10.1021/ac9511612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brzeska H, Martin B, Kulesza-Lipka D, Baines I C, Korn E D. J Biol Chem. 1997;267:4349–4356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanks S K, Hunter T. FASEB J. 1995;9:576–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benner G E, Dennis P B, Masaracchia R A. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21121–21128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.21121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manser E, Huang H-Y, Loo T-H, Chen X-Q, Dong J-M, Leung T, Lim L. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1129–1143. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu C, Whiteway M, Thomas D Y, Leberer E. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15984–15992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.27.15984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin G A, Bollag G, McCormick F, Abo A. EMBO J. 1995;14:1970–1978. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulesza-Lipka D, Brzeska H, Baines I C, Korn E D. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17995–18001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng B, Morrice N A, Groenen L C, Wettenhall R E H. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32233–32240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]