Abstract

Hybrid mice carrying oncogenic transgenes afford powerful systems for investigating loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in tumors. Here, we apply this approach to a neoplasm of key importance in human medicine: mammary carcinoma. We performed a whole genome search for LOH using the mouse mammary tumor virus/v-Ha-ras mammary carcinoma model in female (FVB/N × Mus musculus castaneus)F1 mice. Mammary tumors developed as expected, as well as a few tumors of a second type (uterine leiomyosarcoma) not previously associated with this transgene. Genotyping of 94 anatomically independent tumors revealed high-frequency LOH (≈38%) for markers on chromosome 4. A marked allelic bias was observed, with M. musculus castaneus alleles almost exclusively being lost. No evidence of genomic imprinting effects was noted. These data point to the presence of a tumor suppressor gene(s) on mouse chromosome 4 involved in mammary carcinogenesis induced by mutant H-ras expression, and for which a significant functional difference may exist between the M. musculus castaneus and FVB/N alleles. Provisional subchromosomal localization of this gene, designated Loh-3, can be made to a distal segment having syntenic correspondence to human chromosome 1p; LOH in this latter region is observed in several human malignancies, including breast cancers. Evidence was also obtained for a possible second locus associated with LOH with less marked allele bias on proximal chromosome 4.

Keywords: allelotype, loss of heterozygosity, tumor suppressor gene, transgenic mice, experimental breast neoplasms

Specific losses of heterozygosity (LOH) are observed frequently in a variety of human and murine tumors, underscoring the importance of tumor suppressor gene inactivation as a mechanism in carcinogenesis (1–7). Observing LOH in a genomic location in multiple tumor specimens has been interpreted as reflecting the presence of a tumor suppressor gene in that region (1–3). Allele-specific LOH is often found in tumors associated with familial cancer syndromes, at the site of the responsible gene (1–3, 8, 9). Delineating the boundaries of a minimal region of common LOH among multiple tumors has been a useful approach in positional cloning of candidate novel tumor suppressor genes (1, 2, 10–12).

Mouse genetic systems (and transgenic mouse tumor models in particular) offer a number of useful features for LOH analysis, including the ability to breed genetically uniform and fully “informative” hybrid mice that can provide an essentially unlimited number of tumors (5–7). Previously (7), we conducted a genome-wide search for LOH in two neoplasms—pancreatic insulinomas and gut carcinoid tumors—that developed in hybrid Rip1-Tag2 transgenic mice (13) due to tissue-specific expression of the simian virus 40 early region genes. Frequent allelic loss was observed only for markers on chromosomes 9 and 16. The putative tumor suppressor genes that are involved in these losses, designated Loh-1 and Loh-2, respectively, have been localized to narrow map intervals by identifying the common region of LOH in two large sets of tumors (7, 14). Recently, evidence supporting the suggestion that Loh-2 may normally function by inhibiting angiogenesis has been presented (14). Similar experimental approaches have been used by others to investigate the genetics of tumorigenesis in several mouse models (5, 6, 15–26).

To extend our studies to a transgenic mouse model of a clinically important tumor, we conducted a genome-wide survey for LOH on a large collection of mammary carcinomas and several uterine sarcomas derived from female (FVB/N × Mus musculus castaneus)F1 mice carrying the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV)/v-Ha-ras transgene (27). Crosses with M. musculus castaneus (CAST) mice were employed because of the high genetic polymorphism rate between laboratory mice and this distinct Mus subspecies (7, 28). We found that LOH in tumors frequently occurred for markers on chromosome 4. A profound bias toward loss of the CAST-derived alleles was observed, most often due to apparent loss of the entire CAST-derived chromosome. These results are consistent with the presence of a tumor suppressor gene(s) on mouse chromosome 4 that modulates Hras-mediated mammary tumorigenesis, and for which the CAST allelic configuration is more functionally active than FVB/N; we have named this locus Loh-3. Interestingly, the presence of the CAST allele of Loh-3 in the F1 mice did not change the frequency or latency for development of mammary tumors as compared with the parental FVB/N transgenic line; this result may indicate that inactivation of multiple tumor suppressor genes is necessary for development of these neoplasms (cf. ref. 1). Analysis of the few tumors found to have partial chromosome losses suggests that Loh-3 may be located on distal chromosome 4, in a region syntenic with human chromosome 1p that is thought to harbor at least one important tumor suppressor gene (1–3, 29–32). In addition, the data may suggest the presence of a possible second tumor suppressor gene, on proximal chromosome 4, associated with LOH in this system, but apparently with less allelic bias.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tumor Generation.

MMTV/v-Ha-ras transgenic mice, originally described as line TG.SH (27) and subsequently backcrossed onto the FVB/N (33) background, were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. M. musculus castaneus CAST/EiJ mice were from the Jackson Laboratory. Transgenic F1 females (“study mice”) were identified by Southern blot hybridization (34) of tail DNA samples using the v-Ha-ras probe BS9 (35). Study mice of different degrees of parity were caged together for up to 36 months to observe tumor formation; nontransgenic littermates were caged with the study mice as controls. Tumors were identified by palpation, and they were typically harvested at ≤1-cm diameter size; mammary tumors larger than this were frequently found to undergo very rapid necrotic degeneration. Complete gross necropsy examination was performed at the time of euthanasia or death without tumor. For DNA isolation, the cellular portions of tumors were dissected free of capsule, large vascular elements, and any necrotic debris. DNA was isolated from tumor, tail, and spleen tissue by using a proteinase K digestion–phenol extraction protocol (34).

Simple Sequence Length Polymorphism (SSLP) Genotyping.

A whole-genome survey of tumor DNAs for LOH, using a map of PCR-typeable SSLP markers (28), was performed as described previously (7). Genetic loci that gave robust amplification suitable for detecting LOH on the FVB/N × CAST cross were identified in pilot experiments using parental and F1 DNAs isolated from splenocytes; quantitative image analysis permitted reliable LOH detection in the presence of appreciable contamination of tumor cells by normal diploid cellular elements (7). The SSLP markers used for the initial whole-genome screen were D1MIT4, D1MIT257, D1MIT360, D2MIT317, D2MIT207, D2MIT52, D3MIT23, D3MIT73, D3MIT32, D4MIT103, D4MIT166, D4MIT208, D5MIT24, D5MIT23, D5MIT224, D6MIT170, D6MIT70, D6MIT15, D7MIT56, D7MIT182, D7MIT209, D8MIT60, D8MIT51, D8MIT87, D9MIT161, D9MIT174, D9MIT45, D10MIT28, D10MIT207, D10MIT47, D11MIT15, D11MIT35, D11MIT168, D12MIT82, D12MIT214, D12MIT17, D13MIT15, D13MIT157, D13MIT230, D14MIT201, D14MIT66, D14MIT38, D15MIT10, D15MIT67, D15MIT75, D16MIT129, D16MIT147, D16MIT20, D17MIT144, D17MIT138, D17MIT41, D18MIT30, D18MIT161, D18MIT155, D19MIT79, D19MIT11, D19MIT33, DXMIT136, DXMIT119, and DXMIT60. Additional markers studied on chromosome 4 are shown in Fig. 2. Allele typings were performed as described previously (7, 36), with the exception of marker D4MIT235, for which a 2.5 mM MgCl2 concentration for the PCR amplification was used.

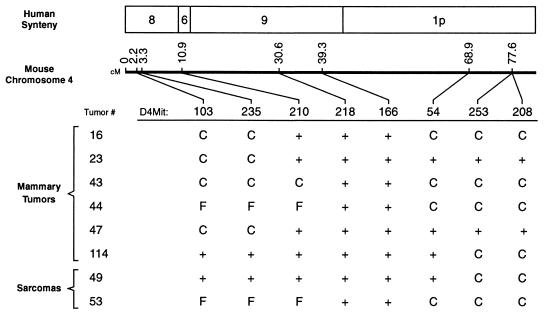

Figure 2.

Table (bottom) lists allele lost (C for CAST, F for FVB/N) for six mammary tumors and two sarcomas showing partial LOH on chromosome 4; a + in a cell in the table denotes no allele loss detected. Middle line shows Massachusetts Institute of Technology database marker locations along chromosome 4 (cM, centimorgans), and top section depicts human syntenic correspondence of mouse chromosome 4 subregions (41).

Statistical Analyses.

Tumor-free survival was calculated using the product-limit method of Kaplan and Meier (37), with censoring of data for mice lost to observation without tumor development; comparisons between subgroups of study mice were made using the log rank test (38). Pairwise statistical comparison tests were made as noted in the text.

RESULTS

Kinetics of Tumorigenesis.

To permit observation of parental genomic imprinting effects in LOH (17, 19, 24), both male and female transgenic FVB/N mice were used for producing the F1 study mice. This experimental design would also allow for possible detection of variations in the mechanism of transgene-induced tumorigenesis arising due to different horizontal transmission of MMTV by lactating FVB/N and CAST mothers (39). Study mice developed mammary tumors between 4 and 28 months of age (Fig. 1); for some of these, up to four anatomically independent mammary tumors were present at the time of harvest. The gross morphological characteristics of these tumors did not vary appreciably between mice or over the duration of the experiment. The histopathological appearance of some of these tumors was examined, and it was carcinoma, as described previously for this transgene (27, 40). Seven aged virgin mice developed leiomyosarcomas of the uterine cervix or horns; the histopathology of these tumors will be described elsewhere. Most of the mice exhibited some degree of exopthalmia (bulging of the eyes) due to Halderian gland hyperplasia (27). Malignant lymphomas were not observed in this experiment, in contrast to a previous report (27). No tumors of any kind were detected in nontransgenic F1 littermate control mice followed for up to 36 months (Fig. 1C).

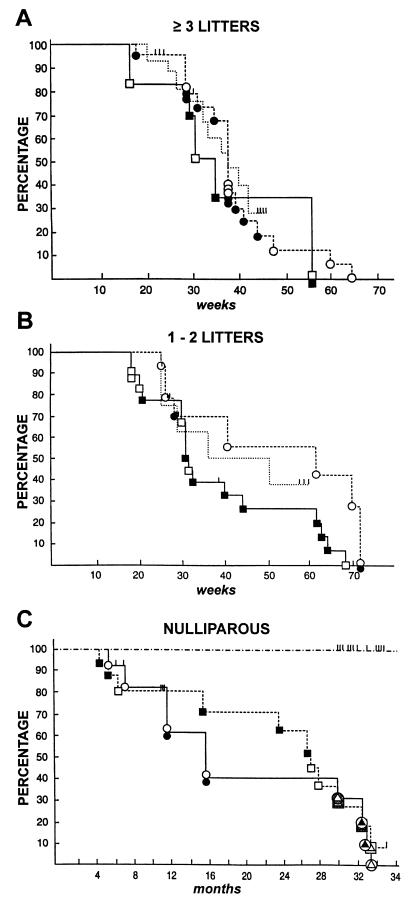

Figure 1.

Kinetics of tumorigenesis and occurrence of LOH in female hybrid study mice that had ≥3 litters (A), 1–2 litters (B), or no litters (C). Tumor-free survival is shown as a function of age for each study mouse having a male (•, ○) or female (▪, □) FVB/N transgenic parent. Each symbol at an event timepoint represents one mouse; a filled symbol denotes occurrence of LOH in one or more tumors harvested from that mouse. Tick marks represent mice lost to follow-up without tumor. Tumor-free survival of parous FVB/N transgenic females is shown as the dotted lines in A and B. In C, seven nulliparous study mice developing sarcomas are designated with symbols having triangular inserts that are filled or not to signify LOH; background shading for three of these indicates no genotyping data available. –⋅–⋅, Control nontransgenic F1 mice.

The reproductive history of the study mice was found to be a determinant of tumor latency in this experiment (Fig. 1): as the number of times the mice had delivered litters of pups increased, the average time to development of one or more mammary tumors by the mice decreased. Mice were therefore grouped by number of litters produced for further analysis. After controlling for the effect of parity in this way, the kinetics with which mammary tumors developed were found to be the same whether the transgenic FVB/N parent was male or female (Fig. 1). The mean number of mammary tumors present at the time of harvest was similar whether the study mice had a female (average of 1.33 tumors per mouse) or a male (average of 1.55 tumors per mouse) transgenic FVB/N parent (Table 1). The frequency (average 1.4 tumors per mouse) and latency (Fig. 1 A and B) of mammary tumorigenesis in the FVB/N transgenic breeding females did not differ from that of the parous study mice.

Table 1.

Frequencies of tumorigenesis and chromosome 4 allele loss

| Parity | Tumor host mice

|

|

|---|---|---|

| (CAST ♀ × FVB/N ♂)F1 | (FVB/N ♀ × CAST ♂)F1 | |

| Mammary carcinomas | ||

| Overall | 42 tumors/32 mice | 48 tumors/31 mice |

| 1.31 tumors/mouse | 1.55 tumors/mouse | |

| 38.1% LOH | 37.5% LOH | |

| ≥3 litters | 22 tumors/17 mice | 9 tumors/6 mice |

| 1.29 tumors/mouse | 1.50 tumors/mouse | |

| 45.5% LOH | 33% LOH | |

| 1–2 litters | 14 tumors/9 mice | 27 tumors/17 mice |

| 1.56 tumors/mouse | 1.59 tumors/mouse | |

| 21.4% LOH | 37.0% LOH | |

| Nulliparous | 6 tumors/6 mice | 12 tumors/8 mice |

| 1.0 tumors/mouse | 1.50 tumors/mouse | |

| 50.0% LOH | 41.7% LOH | |

| Uterine leiomyosarcomas | ||

| Nulliparous | 2/3 LOH + | 0/1 LOH + |

The occurrence of chromosome 4 LOH (partial or complete) in 90 mammary carcinomas and 4 uterine sarcomas is shown in relation to parentage and reproductive history of the hybrid transgenic mice.

LOH Analysis.

An initial group of 74 mammary carcinomas and four uterine sarcomas was surveyed for LOH on a genome-wide basis, using three markers per chromosome. A low overall rate of allelic loss was measured here (Table 2), but a large number of LOH events were detected for markers on chromosome 4. On the basis of these results, this set of tumors was reexamined with a higher density of genetic markers on chromosome 4, and an additional 16 mammary tumors were investigated for chromosome 4 markers only. In total, approximately 38% of these 94 tumors showed allele loss for chromosome 4 markers (Table 2). For many of the tumors, paired normal DNA (from the tail or spleen of the same mouse) was genotyped in parallel to definitively prove LOH. Three of the seven sarcomas were harvested postmortem, and they did not yield DNA of sufficient quality for LOH analysis. No allelic losses in the genomic regions encompassing Trp53, Rb-1, or the mouse homolog of BRCA1 (6) were observed in any of the tumors (Table 2).

Table 2.

LOH in 74* mammary carcinomas and 4 uterine sarcomas

| Chromosome | Percentage of tumors losing allele

|

|

|---|---|---|

| CAST | FVB/N | |

| 1 | 1.3 | |

| 2 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 4† | 37.2 | 3.2 |

| 5 | ||

| 6 | ||

| 7 | 1.3 | |

| 8‡ | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| 9 | 1.3 | |

| 10 | ||

| 11 | ||

| 12 | ||

| 13‡ | 3.8 | 1.3 |

| 14 | ||

| 15 | 1.3 | |

| 16 | 1.3 | |

| 17 | ||

| 18 | 1.3 | |

| 19 | 2.6 | |

| X | ||

Percentage of tumors with LOH at any marker along a chromosome is shown; two tumors having mixed allele loss on chromosome 4 (Fig. 2) are scored as two loss events of each parental type. Allele loss rates were significantly different from the background rate of 1.1% at nominal levels of P < 0.001(†) and P < 0.04 (‡) by two-sided Fisher’s exact test; this background rate is defined by 16 total losses ÷ (78 tumors × chromosomes) (chromosome 4 is excluded). There was no association of chromosome 8 and 13 LOH events with each other or with chromosome 4 LOH. Losses in the regions containing Rb-1 (chromosome 14), Trp53, or the homolog of BRCA1 (chromosome 11) were not observed.

After an initial survey of 74 mammary carcinomas, 90 mammary carcinomas were analyzed for chromosome 4 LOH.

Thirty-four mammary tumors showed LOH on chromosome 4, with 32 of these having loss of CAST alleles exclusively; this bias is highly significant (P ≪ 0.001 by χ2 test). Of these 32 tumors, 27 showed LOH for CAST alleles at all markers examined on chromosome 4. One additional mammary tumor lost FVB/N alleles for all chromosome 4 markers typed. These results suggest loss of an entire homolog, probably by one or more nondisjunction events. We were not able to establish with certainty, using Southern blot hybridization and quantitative densitometry, whether these 28 tumors are haploid or diploid for chromosome 4 sequences (data not shown).

Six mammary tumors displayed partial LOH for chromosome 4 markers (Fig. 2). Five of these lost CAST alleles exclusively, while one tumor (no. 44) had a mixed pattern of LOH: FVB/N alleles were lost proximally and CAST alleles were lost distally. Two of the sarcomas lost CAST alleles on distal chromosome 4, and one of these also lost FVB/N alleles on proximal chromosome 4 (Fig. 2).

The same rate of LOH in tumors was observed for mice regardless of whether the FVB/N transgenic parent was male or female (Table 1); therefore, there was no evidence for parental genomic imprinting effects (see later). The increasing latency for mammary tumor development observed with decreasing parity raised the possibility that the genetic mechanisms of tumor progression could be different for the three reproductive history groups. However, no systematic variation in the rate of LOH on chromosome 4 was observed between these groups (Table 1) or with the time to tumor development (Fig. 1). The rate of LOH on chromosome 4 in the mammary tumors from mice that had multiple tumors at the time of harvest (35%) did not differ significantly from the overall group.

DISCUSSION

LOH in Mouse Tumor Models.

A growing body of published mouse LOH experiments, based upon a variety of established carcinogen or transgene-induced tumor models, reflects increasing appreciation of the power that this approach brings to dissecting the genetic mechanisms of neoplasia in these systems (5–7, 14–26). Mouse chromosome 4 has figured prominently in the findings of several of these studies, with a number of candidate tumor suppressor genes localized there to date (19–26). It is noteworthy that this chromosome contains the syntenic counterparts of human genomic regions 1p32–36 and 9p21–22 (41), and that these regions display frequent LOH in a variety of human tumors (1–3, 29–32, 42, 43). Thus, it seems likely that there is meaningful biological correspondence between mouse tumor models that show allele loss for chromosome 4 markers and some human cancers. The fact that LOH for human 1p32–36 sequences, syntenic with distal mouse chromosome 4, has been noted for both breast carcinomas (29, 30) and uterine leiomyosarcomas (31) is especially intriguing in relation to the results of this study.

Candidate Novel Tumor Suppressor Gene(s) on Mouse Chromosome 4.

We considered the possibility that the frequent loss of the entire CAST-derived homolog observed in the mammary tumors here might reflect only a general instability of this chromosome in neoplastic mammary epithelial cells. However, analogous studies on mammary tumors using CAST-derived hybrid mice and another transgenic model, MMTV/Wnt-1 (44), did not show loss of this kind (K.H., L. Godley, L. Yuschenkoff, E.S.L., and H. E. Varmus, unpublished observations). The v-Ha-ras and Wnt-1 transgene-induced mammary tumors probably develop from closely related cell types, as promoter elements derived from the MMTV long terminal repeat (LTR) were used in constructing both of these lines; comparable loss of CAST chromosome 4 would have been expected in these two tumor models if this process were nonspecific. Similar wholesale loss of one copy of chromosome 4 in tumors was also observed very frequently in lung carcinomas and lymphomas where an exotic Mus subspecies was not employed in breeding the hybrid mice (6, 19, 20, 25). It is most likely, then, that the LOH for chromosome 4 markers detected in this study reflects activity of a gene(s) located there that can suppress mammary tumorigenesis induced by mutant Hras but not Wnt-1. We designate this gene Loh-3. A transgene mapping experiment excluded linkage of the v-Ha-ras sequences to FVB/N alleles for each of seven markers spanning chromosome 4 (data not shown); thus, the CAST specificity of LOH that was found is not attributable to selective retention of the transgene-containing FVB/N-derived homolog in tumor cells. Although other interpretations are tenable, the strain bias for LOH observed here may indicate that the FVB/N allele of Loh-3 is less functionally active as a tumor suppressor gene than the CAST allele.

Location and Identity of Loh-3.

We attempted to more precisely localize Loh-3 by defining a common region of LOH in the six mammary tumors that showed partial allelic losses for chromosome 4 markers (Fig. 2); such an analysis makes the assumption that partial and complete LOH events lead to inactivation of the same gene(s) and promote tumorigenesis equivalently. In contrast to several previous studies (7, 14, 20–25), a simple pattern of overlapping contiguous allelic losses was not found in this experiment. Instead, two distinct regions showed independent partial LOH events at a significant frequency (P < 0.03 by two-sided Fisher’s exact test): five of six tumors showed LOH proximal to D4MIT210, while four of six tumors showed LOH distal to D4MIT54 (Fig. 2). In principle, either of these regions might contain Loh-3, based on the frequency of LOH. However, the distal region showed LOH of CAST alleles only (as seen in the tumors having complete chromosomal LOH), while the proximal region did not show strain-specific loss (Fig. 2). Thus, the Loh-3 locus that drives the strain-specific LOH in most tumors seems likely to lie in the distal region. The results of a preliminary linkage mapping experiment using N2 backcrossed transgenic mice as tumor hosts, in which the correlation between CAST-specific allele loss in tumors and chromosome 4 host haplotype was investigated, also indicated that Loh-3 is distal to D4MIT166 (E.H.R., unpublished observations). The allele loss patterns found in the two uterine sarcomas with LOH were similar to the mammary tumors (Fig. 2) and were in keeping with this assignment of Loh-3 to the distal portion of chromosome 4; it cannot be assumed, however, that the same tumor suppressor genes are necessarily involved in these two different types of neoplasm (1–3).

These tumor partial LOH data (Fig. 2) support the suggestion that two separate tumor suppressor loci on chromosome 4 (one located in the proximal region and the other in the distal region) might be involved in carcinogenesis in this system. The putative locus in the proximal interval appears to be associated with LOH having less strain bias than the more distal one. The existence of two tumor suppressor genes on a chromosome, with inactivation of each of them contributing to neoplasia, may provide an explanation for the high rate at which apparent nondisjunction events serve as the mechanism of LOH (45) in this and some other (21, 25, 45) tumor models.

The murine homologs of p16 (INK4a/MTS1) and p15 (INK4b/MTS2) genes (46) are candidates for the loci responsible for LOH in several tumor models that show chromosome 4 allele losses (19, 20, 23–25). These genes map proximal to D4MIT166 (19, 20, 28) in a region that did not display LOH in any of the tumors having partial allele losses (Fig. 2); this result would tend to argue against p16 and p15 as candidates for Loh-3. In support of this view, no allelic loss at the p16 locus has been identified in any of 53 mammary tumors (ones without gross chromosome 4 LOH) examined (E.H.R, unpublished observations). Most of mouse chromosome 4 distal to D4MIT166 is syntenic with human chromosome 1p32–36 (41), and it is attractive to speculate that Loh-3 is the murine counterpart of one of the suspected human tumor suppressor genes in that genomic region (1–3, 29–32). Loh-3 may correspond to one or more tumor susceptibility genes mapped to distal chromosome 4 in other mouse models (47, 48), although it seems unlikely to be Mom-1 (49), which does not appear to undergo mutational inactivation in tumors (50). For two of the tumors having distal partial allele losses, heterozygosity was preserved at D4MIT54 (Fig. 2), likely indicating that Loh-3 is also distinct from a putative candidate tumor suppressor gene near that locus (21, 24, 25).

Strain-Specific LOH and Tumor Susceptibility.

As noted above, one model to explain the strong strain specificity of LOH is that the CAST allele of Loh-3 is more active as a tumor suppressor than the FVB/N allele. On its face, this model might seem to contradict our finding that (CAST × FVB/N)F1 transgenic mice show the same incidence and latency of tumor development as the parental FVB/N transgenic mice (despite carrying a copy of the more active CAST allele). Such a conclusion, however, would not be justified: a more active allele could well be preferentially lost, but would have no effect on tumor incidence if the loss were not a rate-limiting step of tumorigenesis. Such a situation is seen with the RB1 gene in human small cell lung carcinoma (SCCA): although virtually all of these tumors show complete inactivation of RB1, the presence of a germ-line mutation in this gene does not significantly increase the risk of developing SCCA (1). Knudson has hypothesized that, in the bronchial cells that are the progenitors of SCCA, multiple tumor suppressor genes in addition to RB1 govern proliferation (1). In such a setting, inheritance of an initial gene “hit” in RB1 need not appreciably accelerate the overall kinetics of multistep carcinogenesis (and thereby increase host tumor susceptibility). Loh-3 may function similarly in the MMTV/v-Ha-ras-induced mammary carcinomas; however, the genome-wide survey for LOH did not identify candidate locations for additional tumor suppressor genes of this kind (Table 2).

Previously, strain-specific LOH on chromosome 4 was detected in some lung tumors (19), and in thymic lymphomas (24), obtained from F1 mice. Neither of the parental strains used to construct the hybrid tumor host mice in these experiments displayed a relatively greater susceptibility to tumorgenesis, and the observed allele loss bias was suggested to involve possible tumor suppressor gene silencing by genomic imprinting (cf. refs. 17 and 51). However, our results may indicate that, as in the human system (1), parental allelic differences that influence LOH need not alter the frequency or latency of tumorigenesis in a particular mouse tissue. Genomic imprinting effects could be excluded as the basis for biased allele loss here, because reciprocal crosses were used in constructing the hybrid transgenic mice. Thus, the possibility that strain-related differences in Loh-3 function (or that of another tumor suppressor gene) were responsible for these earlier results, instead of imprinting, can be entertained.

RAS Pathway Signaling and Mammary Carcinogenesis.

Although RAS mutations are not commonly observed in human breast cancers (52), dysregulated RAS pathway signaling appears to exist in many of these tumors, due to a variety of mechanisms. In particular, wild-type RAS participates in some parts of the signaling events (53–56) that result from genetic lesions, such as amplification of ERBB2 and EGFR genes, that are clearly important in the molecular pathogenesis of breast cancer (57). It is likely that some of the phenotypic effects resulting from these lesions are modeled by mutant RAS gene expression (53–56, 58). It may be reasonably expected, then, that tumor suppressor gene alterations associated with v-Ha-ras-induced carcinogenesis in transgenic mouse mammary epithelial cells would be homologous to a subset of those occurring in human breast, and other, cancers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Edison Liu, Steven Ethier, Samir Hanash, and Beverly Mock for thoughtful criticism of the manuscript, and Miriam Meisler for helpful discussions. This work was supported in part by a Clinical Investigator Award from the National Institutes of Health (K08-CA1590) and a pilot grant from the University of Michigan Breast Oncology Program to E.H.R.; by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (HG00098) to E.S.L.; and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (CA44338) and funds from the G. W. Hooper Foundation to J.M.B.

ABBREVIATIONS

- LOH

loss of heterozygosity

- CAST

Mus musculus castaneus

- MMTV

mouse mammary tumor virus

References

- 1.Knudson A G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10914–10921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fearon E R. In: Scientific American Molecular Oncology. Bishop J M, Weinberg R, editors. New York: Scientific American; 1996. pp. 143–178. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leiss J F, Livingston D M. In: Scientific American Molecular Oncology. Bishop J M, Weinberg R, editors. New York: Scientific American; 1996. pp. 111–142. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lasko D, Cavenee W, Nordenskjold M. Annu Rev Genet. 1991;25:281–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.001433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kemp C J, Fee F, Balmain A. Cancer Res. 1993;53:6022–6027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiseman R W, Cochran C, Dietrich W, Lander E S, Soderkvist P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3759–3763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietrich W F, Radany E H, Smith J S, Bishop J M, Hanahan D, Lander E S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9451–9455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavenee W K, Hansen M F, Nordenskjold M, Kock E, Maumenee I, Squire J A, Phillips R A, Gallie B L. Science. 1985;228:501–503. doi: 10.1126/science.3983638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gailani M R, Bale S J, Leffell D J, DiGiovanna J J, Peck G L, Poliak S, Drum M A, Pastakia B, McBride O W, Kase R, Greene M, Mulvhill J J, Bale A E. Cell. 1992;69:111–117. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90122-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dryja T P, Rapaport J M, Joyce J M, Petersen R A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7391–7394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.19.7391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fearon E R, Cho K R, Nigro J M, Kern S E, Simons J W, Ruppert J M, Hamilton S R, Preisinger A C, Thomas G, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Science. 1990;247:49–56. doi: 10.1126/science.2294591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn S A, Schutte M, Hoque A T, Moskaluk C A, da Costa L T, Rozenblum E, Weinstein C L, Fischer A, Yeo C J, Hruban R H, Kern S E. Science. 1996;271:350–353. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanahan D. Nature (London) 1985;315:115–122. doi: 10.1038/315115a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parangi S, Dietrich W, Christofori G, Lander E S, Hanahan D. Cancer Res. 1995;55:6071–6076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bianchi A B, Navone N M, Aldaz C M, Conti C J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7590–7594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Held W A, O’Brien J G, Kerns K, Gallagher J F, Sigmund C D, Gross K W. Cancer Res. 1994;54:6496–6499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Held W A, Pazik J, O’Brien J G, Kerns K, Gobey M, Meis R, et al. Cancer Res. 1994;54:6489–6495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis L M, Caspary W J, Sakallah S A, Maronpot R, Wiseman R, Barrett J C, Elliott R, Hozier J C. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:1637–1645. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.8.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hegi M E, Devereux T R, Dietrich W F, Cochran C J, Lander E S, Foley J F, Maronpot R R, Anderson M W, Wiseman R W. Cancer Res. 1994;54:6257–6264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herzog C R, Wiseman R W, You M. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4007–4010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herzog C R, Wang Y, You M. Oncogene. 1995;11:1811–1815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee G-H, Ogawa K, Nishimori H, Drinkwater N R. Oncogene. 1995;11:2281–2287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyasaka K, Ohtake K, Nomura K, Kanda H, Kominami R, Miyashita R, Kitagawa T. Mol Carcinog. 1995;13:37–43. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940130107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos J, de Castro I P, Herranz M, Pellicer A, Fernandez-Piqueras J. Oncogene. 1996;12:669–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhuang S M, Elkund L K, Cochran C, Rao G N, Wiseman R W, Soderkvist P. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3338–3343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aldaz C M, Liao Q Y, Paladugu A, Rehm S, Wang H. Mol Carcinog. 1996;17:126–133. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2744(199611)17:3<126::AID-MC4>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinn E, Muller W, Pattengale P, Tepler I, Wallace R, Leder P. Cell. 1987;49:465–475. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90449-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dietrich W F, Miller J, Steen R, Merchant M A, Damron-Boles D, et al. Nature (London) 1996;380:149–152. doi: 10.1038/380149a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bieche I, Champeme M H, Lidereau R. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4274–4286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagai H, Negrini M, Carter S L, Gillum D R, Rosenberg A L, Schwartz G F, et al. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1752–1757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sreekantaiah C, Davis J R, Sandberg A A. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:293–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fong C T, White P S, Peterson K, Sapienza C, Cavenee W K, et al. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1780–1785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taketo M, Schroeder A C, Mobraaten L E, Gunning K B, Hanten G, Fox R R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2065–2069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellis R W, DeFeo D, Maryak J M, Young H A, Shih T Y, Chang E, Lowy D R, Scolnick E M. J Virol. 1980;36:408–420. doi: 10.1128/jvi.36.2.408-420.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dietrich W, Katz H, Lincoln S E, Shin H S, Friedman J, et al. Genetics. 1992;131:423–447. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.2.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaplan E L, Meier P. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mantel N. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee F S, Lane T F, Kuo A, Shackleford G M, Leder P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2268–2272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cardiff R D, Sinn E, Muller W, Leder P. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:495–501. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mock B A, Stoye J, Spence J, Jackson I, Eppig J T, et al. Mamm Genome. 1996;6:S73–S96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kamb A, Gruis N A, Weaver-Feldhaus J, Liu Q, Harshman K, Tavtigian S V, et al. Science. 1994;264:436–440. doi: 10.1126/science.8153634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nobori T, Miura K, Wu D J, Lois A, Takabayashi K, Carson D A. Nature (London) 1994;368:753–756. doi: 10.1038/368753a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsukamoto A S, Grosschedl R, Guzman R C, Parslow T, Varmus H E. Cell. 1988;55:619–625. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luongo C, Moser A R, Gledhill S, Dove W F. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5947–5952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quelle D E, Ashmun R A, Hannon G J, Rehberger P A, Trono D, Richter K H, et al. Oncogene. 1995;11:635–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mock B A, Krall M M, Dosik J K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9499–9503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee G H, Bennett L M, Carabeo R A, Drinkwater N R. Genetics. 1995;139:387–395. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dietrich W F, Lander E S, Smith J S, Moser A R, Gould K A, Luongo C, et al. Cell. 1993;75:631–639. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dove W F, Luongo C, Connelly C S, Gould K A, Shoemaker A R, Moser A R, et al. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1994;59:501–507. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1994.059.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schroeder W T, Chao L Y, Dao D D, Strong L C, Pathak S, Riccardi V, et al. Am J Hum Genet. 1987;40:413–420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rochlitz C F, Scott G K, Dodson J M, Liu E, Dollbaum C, Smith H S, et al. Cancer Res. 1989;49:357–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Janes P W, Daly R J, deFazio A, Sutherland R L. Oncogene. 1994;9:3601–3608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Satoh T, Endo M, Nakafuku M, Akiyama T, Yamamoto T, Kaziro Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7926–7929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li N, Batzer A, Daly R, Yajnik V, Skolnik E, Chardin P, et al. Nature (London) 1993;363:85–88. doi: 10.1038/363085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ben-Levy R, Paterson H F, Marshall C J, Yarden Y. EMBO J. 1994;13:3302–3311. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ethier S P. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:964–973. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.13.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Happ B, Hynes N E, Groner B. Cell Growth Differ. 1993;4:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]