Abstract

Neuronal acetylcholine nicotinic receptors (nAChR) are composed of 12 subunits (α2-10, β2-4), of which α3, α5, α7,β2 and β4 subunits are known to exist in the autonomic nervous system (ANS). α5 subunits possess unique biophysical and pharmacological properties. The present study was undertaken to examine the functional role and pharmacological properties of the nAChR α5 subunits in the ANS using mice lacking α5 nAChR subunits (α5–/–). These mice grew to normal size showing no obvious physical or neurological deficit. They also showed normality in thermo- regulation, pupil size and resting heart rate under physiological conditions. The heart rate and rectal temperature did not differ between α5–/– and wild-type mice during exposure to cold stress. An impairment of cardiac parasympathetic ganglionic transmission was observed during high frequency vagal stimulation, which caused cardiac arrest in all wild-type animals while α5–/– mice were more resistant. Deficiency of α5 subunits strikingly increased the sensitivity to a low concentration of hexamethonium, leading to a nearly complete blockade of bradycardia in response to vagal stimulation. Such a concentration of hexamethonium only slightly depressed the effects of vagal stimulation in control mice. Deficiency of α5 subunits significantly increased ileal contractile responses to cytisine and epibatidine. These results suggest that α5 subunits may affect the affinity and sensitivity of agonists and antagonists in the native receptors. Previous studies revealed that α5 subunits form functional receptors only in combination with other α and β subunits. Thus, the data presented here imply that α5 subunits modulate the activity of nAChR in autonomic ganglia in vivo.

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) maintains internal homeostasis by regulating cardiovascular, body temperature, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, exocrine and pupillary functions. The autonomic ganglia contain predominantly neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), which play a central role in neural transmission in the ANS. nAChRs are ligand-gated ion channels that are arranged in a pentameric combination composed of distinct subunits of which 12 have been identified (α2-10 and β2-4) (Anand et al. 1991; Cooper et al. 1991; Sargent, 1993; Changeux & Edelstein, 2001). Of these nAChR subunits, five (α3, α5, α7, β2 and β4) are known to exist in peripheral autonomic neurons (Klimaschewski et al. 1994; Poth et al. 1997; Zhou et al. 1998; Devay etal. 1999; Erkman etal. 2000).

α5 subunits appear to have unique properties in their sequences and their combinations with other subunits. Like all α subunits, the α5 subunit contains a cysteine pair at positions 192-193 (Couturier et al. 1990; Wada et al. 1990; Chini et al. 1992), but it lacks the nearby tyrosine residue (Abramson et al. 1989; Cohen et al. 1991) which has been implicated in high affinity binding of agonists and competitive antagonists (Abramson et al. 1989; Cohen et al. 1991; Tomaselli et al. 1991). In vitro studies have revealed unique biophysical and pharmacological properties of α5 subunits, such as increase of desensitization of nAChRs and Ca2+ permeability (Ramirez-Latorre et al. 1996; Gerzanich et al. 1998) as well as altered affinities and sensitivities to nicotinic antagonists (Yu & Role, 1998), supporting the importance of α5 subunits in ANS function. Studies in heterologous expression systems strongly suggest that α5 subunits can form functional combinations with other α and β subunits (Ramirez-Latorre et al. 1996; Wang et al. 1996). These subunits have been found in chicken embryonic sympathetic neurons (Yu & Role, 1998), chicken ciliary ganglia (Vernallis et al. 1993; Conroy & Berg, 1995) and the human peripheral neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y (which resembles fetal sympathetic neurons in culture) (Wang et al. 1996). The subunit composition α3α5β2, α3α5β4 or α3α5β2β4, respectively, suggests that α5 subunits may be a component of ganglionic receptors in both human and animal ANS ganglia. Several studies have examined the differences between receptors containing an assemblance of different subunits (Ramirez-Latorre et al. 1996; Wang et al. 1996; Gerzanich et al. 1998; Yu & Role, 1998). However, most of these studies were of isolated receptors such as those expressed in Xenopus oocytes. While of importance, the relevance of such biophysical studies to the function of the ANS as a whole is only beginning to be explored. In order to investigate these physiological and pharmacological functions of native α5 subunits in the ANS, we report a series of autonomic tests in mice lacking nAChR subunit α5.

METHODS

Congenic mice lacking α5 subunits (α5–/–) and their wild-type littermate control mice were used for these experiments (Orr-Urtreger et al. 2000). Mice were back-crossed eight generations onto C57Bl/6J background. The mice were housed in group cages, with food and water freely available, in thermostable rooms (21°C). A light-dark schedule of 12:12 h was maintained. The animals used in this study were cared for in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Clark, 1996) and the experiments were carried out with local ethical committee approval. At the end of experiments the animals were killed by injection (I.P.) of an overdose of pentobarbital. The experiments were performed with the experimenter blind to the mouse genotype and the mice were re-genotyped after the animals were killed. Mice lacking α5 nAChRs grew to normal size without showing any obvious physical, neurological or autonomic deficits. No differences of body weight were found between α5–/– and wild-type mice.

Thermoregulation

The mice were kept in individual cages, moving freely. To investigate thermoregulation in α5–/– mice, rectal temperature was measured in an ambient temperature of 21°C and during exposure to an acute cold stress, using a rectal probe (Yokogawa MF-28) inserted to a depth of 1.5 cm. Rectal temperature was measured three times, and the highest temperature was recorded as baseline. The baseline rectal temperature was measured at 14.00 h for 5 days in 21°C. During cold stress (6°C), the rectal temperature was measured at half-hour intervals for 4.5 hours. The mice were then immediately returned to the animal facility, where the rectal temperature continued to be measured until their recovery.

Changes of body temperature were also measured for 210 min after injection of 30 mg kg−1 morphine (Adler et al. 1988), in an attempt to cause central, rather than environmental, hypothermia.

Pupil size changes

Injection of morphine induces mydriasis in small animals, such as mice and rats. The effect is primarily due to disruption of parasympathetic innervation of the iris (Murray et al. 1983; Klemfuss & Adler, 1986). Pupillary diameters were measured using an Olympus binocular microscope with a magnification of X 20. One of the oculars was fitted with a divided 0.1 mm ruler. All the measurements were made while the animals were non-sedated and held gently under the microscope in an ambient temperature of 21°C. Total handling time was less than 5 s. Both pupils of each animal were always measured, and the average value was recorded. (–)-Morphine hydrochloride was injected subcutaneously at a dose of 30 mg kg−1 to groups of mice (Korczyn et al. 1979; Korczyn & Maor, 1982). Pupillary diameter was measured prior to, as well as 15,30,60,90,120,150 and 180 min after drug administration.

Regulation of heart rate

Under pentobarbital (30 mg kg−1, I.P.) anaesthesia, the right cervical vagus was exposed and placed on silver electrodes, connected with a stimulator (Grass SD9). The heart rate (HR) was measured on a polygraph (Grass model 7P6B) with paper speed of 30 mm s−1. For nerve stimulation, voltage was set at 2 V and trains of square wave pulses were delivered (duration, 0.2 ms). The stimulation frequency was gradually increased (5, 10, 20, 40, 60, 100 and 160 pulses s−1). Each train was given for 10 s with 2-5 min intervals. HR was recorded prior to (HRr), as well as during the period of vagal stimulation (HRvs) and immediately after, and 30, 60, 90 and 120 s after each vagal stimulation subsequently until recovery. The effect of vagal stimulation on heart rate was defined as (HRvs − HRr) × 100/HRr. To keep the depth of anaesthesia, additional doses of pentobarbital (10 mg kg−1) were administered at intervals of about 1 h.

To observe the effects of ganglionic blockade on vagal stimulation, hexamethonium (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was injected intra- peritoneally at 3, 15 and 30 mg kg−1 to groups of mice. HRr was measured 10 min after injection of each concentration of hexa- methonium, repeating the vagal stimulations and measurement of HRvs as detailed above.

In separate experiments, HR was measured during exposure to cold stress of 6°C at 30 min intervals for 270 min.

Ileal contractile responses to nicotinic agonists

Preparation of ilea

Mice were killed by cervical dislocation. The abdomen was opened and the ileum carefully removed immediately and kept in Krebs solution with bubbling oxygen containing 5 % CO2. Distal segments (2-2.5 cm long) of ileum from the same animal were cleaned from adhering tissue and used freshly. Preparations were suspended with silk thread number 3 and attached to an isometric force transducer FTO3C, which was connected to a Grass polygraph (model 7B). The response amplitude was calibrated so that each gram of tension equalled 3 cm in amplitude. Before drug administration the ileum segments were allowed to equilibrate for at least 1 h at resting tension of 1 g in a 10 ml organ bath filled with Krebs solution, kept at 37°C and constantly aerated with bubbling oxygen containing 5 % CO2 with replacement of the Krebs solution every 20 min.

The optimal concentrations to elicit contractile responses were determined in preliminary experiments. The non-specific muscarinic agonist, bethanechol and the nicotinic agonists cytisine, dimethylphenylpiperazinium iodide (DMPP) and nicotine itself were used at concentrations of 0.1, 1, 3, 10, 30 and 100 μm. The nicotinic agonist epibatidine was applied at concentrations of 0.01, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3 and 10 μm (all drugs were Sigma products). Log concentration-response curves were drawn for wild-type mice. For each drug, experiments were performed on ilea of six mice. The results showed that consistent concentration-response curves were elicited for these drugs. Maximal responses were induced by bethanechol, cytisine, DMPP and nicotine at concentrations of 10-30 μm and by epibatidine at concentrations of 0.1-0.3 μm. The response to the four nicotinic agonists was independent of the order of administration. For subsequent studies, each agonist was used at a single concentration (cytisine 10 μm, DMPP 10 μm, nicotine 10 μm and epibatidine 0.1 μm), repeated three times in the same preparation. These concentrations evoked efficient and consistent responses and no tachyphylaxis was observed.

Injection protocol

To characterize the contractile responses to different nicotinic agonists, bethanechol was used as a reference agent, applied in progressively increasing concentrations to give a final concentration of 1-10 μm. The agonists were injected as follows: bethanechol (1, 3 and 10 μm), cytisine (10 μm), DMPP (10 μm), epibatidine (0.1 μm) and nicotine (10 μm) at 40min intervals with four washouts following each administration of drug. At the end of the test bethanechol 3 μm was applied to ensure the preparations were still viable.

Data analysis

The contractile responses to ganglionic agonists were calculated as a percentage of the response to 10 μm bethanechol in the same preparation. The data from the four preparations from the same mouse were averaged. Bonferroni multiple comparison tests were used for comparing the responses of α5–/– mice and their wild- type controls.

RESULTS

Physiological normality of α5–/– mice

All the α5–/– mice grew to normal size showing no obvious physical, neurological or autonomic deficit.

Rectal temperatures

The rectal temperatures of the α5–/– (n = 13) and wild-type mice (n = 27) in ambient temperature of 21°C were similar (mean 38.5 ± 0.2 and 38.4 ± 0.3°C, respectively). During exposure to cold stress, the rectal temperature of the mutant and wild-type mice decreased gradually to 26.7 ± 4.3 and 28.6 ± 5.4°C, respectively (P > 0.05, unpaired t test) after 270 min, with similar recovery after being returned to 21°C ambient temperature (data not shown).

After injection of 30 mg kg−1 morphine, hypothermia developed within 30 min, reaching a nadir of 34.3 ± 0.9 and 34.4 ± 0.8°C in α5–/– (n = 7) and wild-type mice (n = 16), respectively. The rectal temperature recovered to baseline at 240 min after injection of the drug. There was no difference between the two groups of mice.

Pupillary size

All the mice showed normal pupillary size. The mean pupil diameters were 0.51 ±0.16 and 0.52 ± 0.12 mm in α5–/– mice (n = 15) and in wild-type mice (n = 25), respectively. Administration of (–)-morphine hydrochloride (30 mg kg−1) caused a mydriatic effect. The maximal pupillary sizes were 1.81 ±0.94 and 1.80 ± 0.37 mm in α5–/– (n = 11) and wild-type (n = 14) mice, respectively. Thus, deficiency of α5 subunits did not change the effects of morphine on parasympathetic ganglionic transmission.

Heart rate

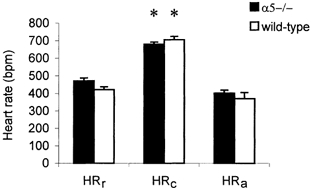

The heart rates of mice were similar and not significantly different between the α5–/– (n = 14) and wild- type (n = 23) mice at rest, during exposure to cold stress or when anaesthetized (fig. 1). In awake mice the resting heart rates (HRr) were 470 ± 61 and 421 ± 82 beats min−1, respectively. Exposure to cold stress induced extreme tachycardia in both strains of mice. Figure 1 illustrates the HR 30 min after exposure to 6°C in α5–/– (n = 8) and wild-type (n = 7) mice, which were not significantly different (680 ± 52 and 706 ± 32 beats min−1, respectively, but significantly higher than that at rest, P < 0.001, t test). The HR under pentobarbital anaesthesia was also similar inα5–/– (n = 7) and wild-type (n = 6) mice, 401 ± 94 and 370 ± 43 beats min−1, respectively, although interestingly in both awake and anaesthetized states the α5–/– mice had a slightly higher HR.

Figure 1. Heart rate of α5–/– and wild-type mice.

HRr, the heart rate (beats min−1, bpm) in awake (α5–/–, n = 14 and wild-type, n = 23) mice at rest (column 1);HRc, the heart rate 30 min after exposure to cold stress (column 2) in α5–/– (n = 8) and wild-type (n = 7) mice; HRa, resting heart rate of α5–/– (n = 7) and wild-type (n = 6) mice under anaesthesia (column 3). There was no significant difference in heart rate between mutant and controlmice. *P < 0.001, t test (HRc vs. HRr). Vertical bars indicate s.e.m.

Vagal stimulation

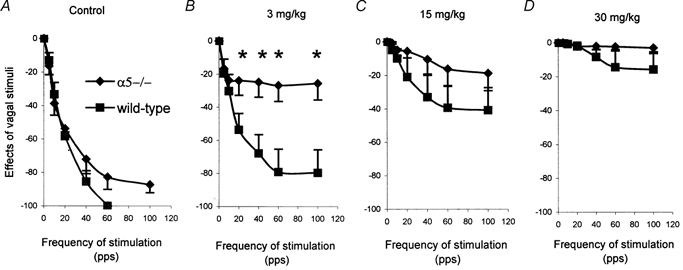

Vagal stimulation caused a frequency-dependent brady-cardia and finally asystole in both mutant and wild-type mice (Fig. 2A). In α5–/– mice at 5 and 10 pulses s−1stimulation the HR was about 16 and 39 % lower than at baseline, respectively, while in the wild-type mice the HR was 15 and 33 % lower than their baseline, respectively (Fig. 2A). Stimulation at 60 pulses s−1 caused asystole in all six control mice, while only in three out of seven α5–/– mice (χ2 = 4.95, P < 0.05). The remaining four α5–/– mice did not develop asystole even after maximal stimulation (160 pulses s−1/5 V), but their HRvs was 70 % lower than their baseline (HRvs = 123 ± 34 beats min−1).

Figure 2. Effects of vagal stimulation on heart rate and its blockade by hexamethonium in α5–/– (n = 7) and wild-type (n = 6) mice.

The effects of vagal stimulation on heart rate (HR) are presented as (HRvs − HRr) × 100/HRr. HRvs, HR following vagal stimulation. HRr, resting HR before each vagal stimulation. pps, pulses s−1. Each vagal stimulation was given for 10 s at 5 min intervals (2 V, 0.2 ms duration). A, baseline of effects of vagal stimulation on HR. B, blockade by 3 mg kg−1 of hexamethonium. C, blockade by 15mg kg−1 of hexamethonium. D, blockade by 30 mg kg−1 of hexamethonium. *P < 0.01, t test, α5–/– vs. control mice. The vertical bars indicate s.e.m.

Different concentrations of hexamethonium failed to alter the HR at rest in both mutant and control mice. However, the response to vagal stimulation showed striking differences between the two strains. While 30 mg kg−1 of hexamethonium completely blocked (Fig. 2D) the HR responses in both α5–/– and wild-type mice, lower concentrations showed a differential sensitivity of α5–/– mice to hexamethonium. For example, while 3 mg kg−1produced only a slight depression of the vagal response in wild-type mice, a nearly complete abolition of the response to vagal stimulation occurred in α5–/– mice (Fig. 2B). Asystole was completely eliminated by all concentrations of hexamethonium in both mutant and control mice, except for three out of six control mice at 3 mg kg−1hexamethonium (χ2 = 0.18).

Contractile responses of ileum to ganglionic agonists

Preliminary experiments revealed that the doses at a final concentration of 10 μm for cytisine, DMPP and nicotine and 0.1 μm for epibatidine induced efficient submaximal ileal contractions. There was no tachyphylaxis in either α5–/– or wild-type mice.

Bethanechol induced a dose-dependent contractile response in ilea. There was no difference in the mean magnitude of contraction between mutant (n = 6) and wild-type (n = 20) mice ilea in different concentrations (P > 0.05, t test, Table 1). A single application giving a final concentration of 3 μm bethanechol was repeated after administration of all nicotinic agonists, with similar responses to that induced by the same dose at the beginning of the experiments, ensuring that the ilea were still viable.

Table 1.

Amplitude of contractile responses to bethanechol in α5–/– and wild-type mice

| Concentration of bethanechol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 μm | 3 μm | 10 μm | *3 μm | |

| α5–/– | 0.55 ± 0.15 | 0.71 ± 0.11 | 1.01 ± 0.11 | 0.73 ± 0.15 |

| Wild-type | 0.50 ± 0.12 | 0.69 ± 0.14 | 0.92 ± 0.16 | 0.69 ± 0.14 |

The mean contractile responses to bethanechol in α5–/– (n = 6) and wild-type (n = 20) mice. Amplitudes of responses (in grams) are given as mean ± S.D. There was no difference in response between ilea of mutant and wild-type mice in different concentrations of bethanechol (P > 0.05, t test).

Repeated administration of bethanechol at the end of the experiments.

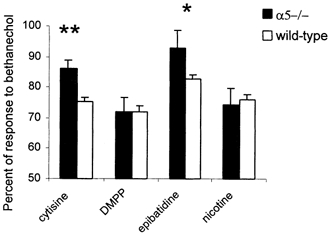

The agonist-induced responses of the ileum in α5–/– and wild-type mice are illustrated in Fig. 3. A significantly higher response was observed to cytisine and epibatidine in α5–/– mice that were 11 % (P < 0.01, t test) and 10 % (P < 0.05, Bonferroni multiple comparison tests) higher than that in wild-type mice. The responses to DMPP and nicotine were similar in α5–/– mice and wild-type mice (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Ileal contractile responses to nicotinic agonists in α5–/– (n = 6) and wild-type (n = 20) mice.

Ileal contractile responses are represented as a percentage of response to bethanechol at a concentration of 10 μm. The nicotinic agonists were used at concentrations of 10 μm for cytisine, dimethylphenylpiperazinium iodide (DMPP) and nicotine and 0.1 μm for epibatidine. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Bonferroni multiple comparison tests, in α5–/– mice compared to littermate wild-type animals. Vertical bars indicate s.e.m.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the functional role and pharmacological properties of α5 nAChR subunits using mice genetically lacking these subunits. Results of studies using knockout animals should be interpreted cautiously. The α5 subunit is not indispensable, as is evidenced by the apparent normal development of the mutated mice. Obviously, other subunits can form functional receptor compositions that will replace the normally existing, α5- containing, nicotinic receptors in the ANS and elsewhere. Thus an intact response or behaviour in α5 knockout animals cannot be taken to imply that α5 subunits are not normally involved in these functions. On the other hand, any abnormal response or behaviour seen in these knockout animals suggests that α5 subunits are normally involved in this function. The data obtained from our study show not only normal growth and development, but also normality of α5–/– mice in body thermoregulation, pupil size and heart rate under physiological conditions. Based on these results, we suggest that although α5 nAChR subunits are normally present in the ANS (Poth et al. 1997; Yu & Role, 1998), nicotinic receptors containing α5 sub- units are not essential for the transmission the autonomic nervous signals for these functions. Nevertheless, α5–/– mice were not normal. Cardiac parasympathetic ganglionic transmission induced by direct cervical vagal stimulation was less effective in knockout animals. This probably implies that the ACh released from vagal terminals is less effective at stimulating the intracardiac parasympathetic postsynaptic nicotinic receptors, although this is only expressed when the stimulation is almost maximal. Strikingly, the deficiency of α5 subunits increased the sensitivity to a low concentration of hexamethonium leading to a nearly complete elimination of HR response to vagal stimulation (Fig. 2). Such a concentration of hexa- methonium only slightly depressed the effects in control mice. This observation is also consistent with a reduced effect of ACh, which is only expressed when a substantial proportion of nicotinic receptors are blocked by hexa- methonium. On the other hand, deficiency of α5 subunits significantly increased ileal contractile responses to cytisine and epibatidine.

In principle, elimination of one subunit can change the ganglionic function in several ways. Firstly, it is possible that since receptors with this type of subunit will not be formed, the total number of receptors will be reduced, possibly resulting in diminished response to ACh. However, we do not necessarily know what is the concentration of the ACh receptors in the specific system, and whether there are enough remaining receptors to prevent this presumed effect. It may also be that the remaining receptors, without the knocked-out subunit, are composed of subunits which are more effective than the lost ones. Alternatively it may be that the system will compensate for the lack of the subunit and synthesize the normal (or even higher) number of receptors consisting of other constructs, which again may respond differently to ACh than the deleted ones, theoretically even enhancing the response to ACh. In addition we may expect to see differences in the effects of cholinomimetic drugs and of antagonists, since these may need specific subunits for ligation.

The physiological relevance of α5 receptor subunits depends either on their abundance, as well as on their association with other nAChR subunit constructs. In heterogeneous expression system, α5 subunits cannot form functional channels when they are expressed alone or in combination with any other single α or β subunit (Conroy et al. 1992; Ramirez-Latorre et al. 1996; Wang et al. 1996). The functional compositions can be with another kind of α subunit and one (or two) kinds of β subunits, such as α3α5β2, α3α5β4 or α3α5β2β4. (Ramirez-Latorre et al. 1996; Wang et al. 1996; Fucile et al. 1997; Nelson & Lindstrom, 1999). In the ANS, studies showed varied abundance of α5 subunit distribution and subunit composition in different tissues. For example, rat intra- cardiac ganglia cultured parasympathetic neurons express α5 subunit mRNA in about 30 % of detected neurons (co-expressed in 30 % of detected neurons with α3 (100 %) andβ2 (55 %) or β4 (55 %) subunits (Poth et al. 1997), but in all the neurons in rat cervical sympathetic ganglia (Skok et al. 1999). In chick ciliary ganglion neurons, which normally express α3, α5, β2 and β4 subunits, α5 subunits were present in about 80 % of neurons (Conroy & Berg, 1995). Although they do not form ACh binding sites, α5 subunits participate in the formation of ion channels (Wang et al. 1996; Nelson & Lindstrom, 1999; Groot-Kormelink et al. 2001). Previous studies have shown that α5 subunits altered channel properties when co-expressed with α3-containing receptors, such as α3β2 and α3β4 receptors in different degrees in an expression system, for example, they increase desensitization and Ca2+ permeability of nAChR (Wang et al. 1996; Gerzanich et al. 1998; Yu & Role, 1998). The α3α5β4 nAChRs have a higher conductance, longer open time and an increased burst duration in comparison to channels composed of only α3β4 subunits (Wang et al. 1996; Nelson & Lindstrom, 1999). These results suggest the physiological importance of α5 subunits in the ANS. Thus, deficiency of α5 subunits can be presumed to influence autonomic ganglionic trans- mission to end-organs. However, in the present study, most autonomic physiological functions, for example in cardiac regulation, did not differ between α5–/– and wild-type mice. Similar results in HR at rest have also been seen in several reported results relating to HR regulation, such as in mice overexpressingb1-adrenergic receptor kinase 1 inhibitor (Koch et al. 1995), G-protein-coupled receptor kinase (Rockman et al. 1996) and in knockout mice lacking b1-adrenergic receptors (Rohrer et al. 1996) and cardiac G-protein-potassium channel subunit GIRK4 (Wickman et al. 1998). Thus, HR is determined by several regulation factors. The normality of HR in α5–/– mice suggests at least two mechanistic possibilities on ganglion transmission to the heart. First, it has been evident that α5 subunits can be functional when combined with other α and β subunits, for example, α3β2 and α3β4 (Ramirez-Latorre etal. 1996; Wang et al. 1996), which are important components in autonomic transmission (Xu et al. 1999a, b). Receptors of α3β2 or α3β4 composition are functional with or without α5 subunits and they could allow normal physiological function in vivo. Based on this prerequisite, the second possibility is that cardiac nAChRs or their signal transduction may have adapted during development in the α5–/– mice, probably by replacing α5 with other nAChR subunits, e.g. β subunits (Wang et al. 1996; Nelson & Lindstrom, 1999) or that the total amount of missed receptors did not reach a critical level influencing ganglionic transmission under physiological conditions. However with excessive excitation (for example after high frequency vagal stimulation) ‘resting receptors’ in the repertoire (Margiotta & Gurantz, 1989) are called into play and remaining receptors cannot deliver the full effect of the released ACh. Our results show that differences between the α5–/– and wild-type controls were only minimal during the normal repertoire of behaviour examined, and differences were seen mainly when pharmacological manipulations were applied. This suggests that the α5–/– receptors respond differently when drugs with slightly altered affinity to the nicotinic receptors (whether agonists or antagonists) are used. This may suggest that genetic changes (even small poly- morphisms) while consistent with normal development and function, may underlie abnormal responses to drugs. Although so far we are unable to determine the exact composition of nAChRs in mice lacking α5 subunits, the results suggest that the participation of α5 subunits in formation of ion channels, probably affects ganglion transmissions.

Our results showed supersensitive responses to hexa- methonium in blockade of ACh transmission to heart induced by direct vagal stimulation (Fig. 2) and increased ileal contractile responses to nicotinomimetic drugs, cytisine and epibatidine, but not to nicotine itself or DMPP (Fig. 3) in mice lacking α5 subunits. Studies in native receptors and in heterologously expressed α5- containing receptors, showed functional deletion of the α5 subunits by antisense oligonucleotide treatment in embryonic chick sympathetic neurons increased 4-fold the apparent affinities for cytisine, as well as for ACh and nicotine. The whole cell currents elicited by ACh are 25 % larger in α5 subunit deleted neurons than that in controls (McGehee & Role, 1995; Yu & Role, 1998). The inclusion of α5 subunits altered the affinities and sensitivities to nicotinic agonists by different degrees in α3-containing nAChRs expressed in heterologous expression systems and showed that these effects are β subunit composition related (Wang et al. 1996; Gerzanich et al. 1998; Yu & Role, 1998; Nelson & Lindstrom, 1999). For example, incorporating α5 subunits in recombinant human α3β2 receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes, increased the sensitivity for ACh and nicotine, but the EC50 for cytisine did not change and for DMPP it was reduced. While the sensitivity to ACh, nicotine and DMPP were similar between α3α5β4 and α3β4 receptors, the incorporation of α5 subunits into α3β4 receptors increased the sensitivity to cytisine (Wang et al. 1996; Gerzanich et al. 1998). The efficacies of the drugs were also changed: nicotine switching from a partial agonist in α3β2 receptors to full agonist in α3α5β2 receptors, and DMPP increasing in efficacy compared with ACh (Wang et al. 1996; Gerzanich et al. 1998; Nelson & Lindstrom, 1999). The different influence of α5 in α3-containing receptors to agonists may be based on profiles of α3 and b composition themselves. In vitro studies show the differences between β2 and β4 subunits on the affinity of agonists, such as epibatidine and DMPP on β2-containing receptors, while cytisine is thought effective in β4-containing receptors (Covernton et al. 1994; Parker et al. 1998). Also β2-containing receptors have higher affinity and sensitivity to nicotine and ACh than β4-containing receptors; nicotine is a partial agonist in β4-containing receptors (Luetje & Patrick, 1991; Papke & Heinemann, 1991; Patrick et al. 1993; Covernton et al. 1994; Sivilotti et al. 1997). Hexamethonium is a non- selective ganglionic blocker; it blocks all α3β2 and α3β4 receptors with or without α5 subunits (Nelson & Lindstrom, 1999), although according to our results of increased sensitivity to hexamethonium blockade of vagal stimulation and the increased ileal contractile responses to cytisine and epibatidine in α5–/– mice, it seems that the pharmacological changes are not due to loss of ACh binding sites, but appear because the α5 subunits seem to regulate agonist and antagonist ligand-binding to the nicotinic receptors and may modulate the interactions between other α and β subunits in vivo. These effects of α5 subunits altering pharmacological and physiological properties may be due to their structural participation in functional receptor complexes and due to the contributions of α5 subunit M2 segment to the lining of the ion channels (Ramirez-Latorre et al. 1996). Although they are not directly involved in the agonist binding sites, α5 subunits may be responsible for the changes in overall structure of the AChRs, which influence the ability of the AChRs to make the concerted changes in subunit orientation needed for channel opening (Ramirez-Latorre et al. 1996; Wang et al. 1996; Gerzanich et al. 1998), resulting in alteration of the EC50 or efficacy of some drugs to the receptors.

To date, the pharmacological data obtained from studies in vitro are poorlymatched to in vivo results (Sivilotti etal. 1997; Nelson & Lindstrom, 1999). Furthermore, compensatory effects might occur during animal development (Yu & Role, 1998). Although previous studies have shown distinct differences in pharmacological properties between α3β2 and α3β4 receptors in vitro (for example, higher efficiency of cytisine on β4-containing receptors and of nicotine, epibatidine and DMPP onβ2-containing receptors), we are unable to fully explain the increased ileal responses to cytisine and epibatidine, but not to nicotine and DMPP in α5–/– mice. In similar experiments with the same agonists, ileal contractions were greatly reduced to all four agonists in β4 knockout mice (Wang et al. 2001), while there was no significant reduction in responses to the four agonists in β2 knockout mice (authors' unpublished data). These data suggest that the effects of α5 subunits are not drug selective in native receptors.

In summary, α5 nAChR subunits are normally present in ANS ganglia and possess unique physiological and pharmacological properties, probably modulating post- synaptic nAChR channels responses to endogenous ACh and regulating responses to ganglion drugs in receptor complexes. Since the autonomic ganglia operate without direct inhibition (Skok, 1983), such effects of α5 subunits may lower the safety factor in transmission systems.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Sieratzki Chair ofNeurology, Tel Aviv University, and the Miriam Turjanski de Gold and Dr Roberto Gold Fund for Neurological Research and by a NARSAD award to A. Orr-Urtreger. This work is part of the PhD thesis submitted by N. Wang to Tel Aviv University.

REFERENCES

- Abramson SN, Li Y, Culver P, Taylor P. An analog of lophotoxin reacts covalently with Tyr190 in the alpha-subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264:12666–12672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler MW, Geller EB, Rosow CE, Cochin J. The opioid system and temperature regulation. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 1988;28:429–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.28.040188.002241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand R, Conroy WG, Schoepfer R, Whiting P, Lindstrom J. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes have a pentameric quaternary structure. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:11192–11198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changeux J, Edelstein SJ. Allosteric mechanisms in normal and pathological nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2001;11:369–377. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chini B, Clementi F, Hukovic N, Sher E. Neuronal-type alpha-bungarotoxin receptors and the alpha 5-nicotinic receptor subunit gene are expressed in neuronal and nonneuronal human cell lines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:1572–1576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JB, Sharp SD, Liu WS. Structure of the agonist-binding site of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. [3H] Acetylcholine mustard identifies residues in the cation-binding subsite. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:23354–23364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy WG, Berg DK. Neurons can maintain multiple classes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors distinguished by different subunit compositions. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:4424–4431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy WG, Vernallis AB, Berg DK. The alpha 5 gene product assembles with multiple acetylcholine receptor subunits to form distinctive receptor subtypes in brain. Neuron. 1992;9:679–691. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper E, Couturier S, Ballivet M. Pentameric structure and subunit stoichiometry of a neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Nature. 1991;350:235–238. doi: 10.1038/350235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier S, Erkman L, Valera S, Rungger D, Bertrand S, Boulter J, Ballivet M, Bertrand D. Alpha 5, alpha 3, and non-alpha 3. Three clustered avian genes encoding neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-related subunits. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:17560–17567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covernton PJ, Kojima H, Sivilotti LG, Gibb AJ, Colquhoun D. Comparison of neuronal nicotinic receptors in rat sympathetic neurones with subunit pairs expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of Physiology. 1994;481:27–34. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devay P, McGehee DS, Yu CR, Role LW. Target-specific control of nicotinic receptor expression at developing interneuronal synapses in chick. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:528–534. doi: 10.1038/9183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkman L, Matter J, Matter-Sadzinski L, Ballivet M. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene expression in developing chick autonomic ganglia. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2000;393:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucile S, Barabino B, Palma E, Grassi F, Limatola C, Mileo AM, Alema S, Ballivet M, Eusebi F. Alpha 5 subunit forms functional alpha 3 beta 4 alpha 5 nAChRs in transfected human cells. NeuroReport8. 1997:2433–2436. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199707280-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerzanich V, Wang F, Kuryatov A, Lindstrom J. Alpha 5 subunit alters desensitization, pharmacology, Ca++ permeability and Ca++ modulation of human neuronal alpha 3 nicotinic receptors. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;286:311–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groot-Kormelink PJ, Boorman JP, Sivilotti LG. Formation of functional alpha3beta4alpha5 human neuronal nicotinic receptors in Xenopus oocytes: a reporter mutation approach. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2001;134:789–796. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemfuss H, Adler MW. Autonomic mechanisms for morphine and amphetamine mydriasis in the rat. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1986;238:788–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimaschewski L, Reuss S, Spessert R, Lobron C, Wevers A, Heym C, Maelicke A, Schroder H. Expression of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the rat superior cervical ganglion on mRNA and protein level. Brain Research. Molecular Brain Research. 1994;27:167–173. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch WJ, Rockman HA, Samama P, Hamilton RA, Bond RA, Milano CA, Lefkowitz RJ. Cardiac function in mice overexpressing the beta-adrenergic receptor kinase or a beta ARK inhibitor. Science. 1995;268:1350–1353. doi: 10.1126/science.7761854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korczyn AD, Boyman R, Shifter L. Morphine mydriasis in mice. Life Sciences. 1979;24:1667–1673. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(79)90251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korczyn AD, Maor D. Central and peripheral components of morphine mydriasis in mice. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and behavior. 1982;17:897–899. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90468-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luetje CW, Patrick J. Both alpha- and beta-subunits contribute to the agonist sensitivity of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:837–845. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00837.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margiotta JF, Gurantz D. Changes in the number, function, and regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors during neuronal development. Developmental Biology. 1989;135:326–339. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS, Role LW. Physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed by vertebrate neurons. Annual Review of Physiology. 1995;57:521–546. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RB, Adler MW, Korczyn AD. The pupillary effects of opioids. Life Sciences. 1983;33:495–509. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(83)90123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson ME, Lindstrom J. Single channel properties of human alpha3 AChRs: impact of beta2, beta4 and alpha5 subunits. Journal of Physiology. 1999;516:657–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0657u.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr-Urtreger A, Kedmi M, Karmeli F, Yaron Y, Rachmilewitz D. The severity of experimental colitis in mice is dependent on the presence of the alpha5 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR).subunit. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2000;67:184. [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Heinemann SF. The role of the beta 4-subunit in determining the kinetic properties of rat neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine alpha 3-receptors. Journal of Physiology. 1991;440:95–112. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MJ, Beck A, Luetje CW. Neuronal nicotinic receptor beta2 and beta4 subunits confer large differences in agonist binding affinity. Molecular Pharmacology. 1998;54:1132–1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick J, Sequela P, Vernino S, Amador M, Luetje C, Dani JA. Functional diversity of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Progress in Brain Research. 1993;98:113–120. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poth K, Nutter TJ, Cuevas J, Parker MJ, Adams DJ, Luetje CW. Heterogeneity of nicotinic receptor class and subunit mRNA expression among individual parasympathetic neurons from rat intracardiac ganglia. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:586–596. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00586.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Latorre J, Yu CR, Qu X, Perin F, Karlin A, Role L. Functional contributions of alpha5 subunit to neuronal acetylcholine receptor channels. Nature. 1996;380:347–351. doi: 10.1038/380347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockman HA, Choi DJ, Rahman NU, Akhter SA, Lefkowitz RJ, Koch WJ. Receptor-specific in vivo desensitization by the G protein-coupled receptor kinase-5 in transgenic mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:9954–9959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer DK, Desai KH, Jasper JR, Stevens ME, Regula DP, JR, Barsh GS, Bernstein D, Kobilka BK. Targeted disruption of the mouse beta1-adrenergic receptor gene: developmental and cardiovascular effects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:7375–7380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent PB. The diversity of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1993;16:403–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.16.030193.002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivilotti LG, McNeil DK, Lewis TM, Nassar MA, Schoepfer R, Colquhoun D. Recombinant nicotinic receptors, expressed in Xenopus oocytes, do not resemble native rat sympathetic ganglion receptors in single-channel behaviour. Journal of Physiology. 1997;500:123–138. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skok MV, Voitenko LP, Voitenko SV, Lykhmus EY, Kalashnik EN, Litvin TI, Tzartos SJ, Skok VI. Alpha subunit composition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the rat autonomic ganglia neurons as determined with subunit - specific anti-alpha(181-192) peptide antibodies. Neuroscience. 1999;93:1427–1436. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skok VI. Fast synaptic transmission in autonomic ganglia. In: Elfvin L-G, editor. Autonomic ganglia. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1983. pp. 265–280. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli GF, McLaughlin JT, Jurman ME, Hawrot E, Yellen G. Mutations affecting agonist sensitivity of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biophysical Journal. 1991;60:721–727. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82102-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernallis AB, Conroy WG, Berg DK. Neurons assemble acetylcholine receptors with as many as three kinds of subunits while maintaining subunit segregation among receptor subtypes. Neuron. 1993;10:451–464. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90333-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada E, McKinnon D, Heinemann S, Patrick J, Swanson LW. The distribution of mRNA encoded by a new member of the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor genefamily (alpha 5). in the rat central nervous system. Brain Research. 1990;526:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90248-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Gerzanich V, Wells GB, Anand R, Peng X, Keyser K, Lindstrom J. Assembly of human neuronal nicotinic receptor alpha5 subunits with alpha3, beta2, and beta4 subunits. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:17656–17665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Orr-Urtrege A, Chapman J, Rabinowitz R, Nachman R, Korczyn AD. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits alpha5 and beta4 in ileal contractile response to ganglionic agonists. Annals of Neurology. 2001;50:S35–S36. [Google Scholar]

- Wickman K, Nemec J, Gendler SJ, Clapham DE. Abnormal heart rate regulation in GIRK4 knockout mice. Neuron. 1998;20:103–114. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Gelber S, Orr-Urtreger A, Armstrong D, Lewis RA, Ou CN, Patrick J, Role L, De Biasi M, Beaudet AL. Megacystis, mydriasis, and ion channel defect in mice lacking the alpha3 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999a;96:5746–5751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Orr-Urtreger A, Nigro F, Gelber S, Sutcliffe CB, Armstrong D, Patrick JW, Role LW, Beaudet AL, De Biasi M. Multiorgan autonomic dysfunction in mice lacking the beta2 and the beta4 subunits of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999b;19:9298–9305. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09298.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CR, Role LW. Functional contribution of the alpha5 subunit to neuronal nicotinic channels expressed by chick sympathetic ganglion neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1998;509:667–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.667bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Deneris E, Zigmond RE. Differential regulation of levels of nicotinic receptor subunit transcripts in adult sympathetic neurons after axotomy. Journal of Neurobiology. 1998;34:164–178. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19980205)34:2<164::aid-neu6>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]