Abstract

Several classes of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) are inhibited by G proteins activated by receptors for neurotransmitters and neuromodulatory peptides. Evidence has accumulated to indicate that for non-L-type Ca2+ channels the executing arm of the activated G protein is its βγ dimer (Gβγ). We report below the existence of two Gβγ-binding sites on the A-, B-, and E-type α1 subunits that form non-L-type Ca2+ channels. One, reported previously, is in loop 1 connecting transmembrane domains I and II. The second is located approximately in the middle of the ca. 600-aa-long C-terminal tails. Both Gβγ-binding regions also bind the Ca2+ channel β subunit (CCβ), which, when overexpressed, interferes with inhibition by activated G proteins. Replacement in α1E of loop 1 with that of the G protein-insensitive and Gβγ-binding-negative loop 1 of α1C did not abolish inhibition by G proteins, but the exchange of the α1E C terminus with that of α1C did. This and properties of α1E C-terminal truncations indicated that the Gβγ-binding site mediating the inhibition of Ca2+ channel activity is the one in the C terminus. Binding of Gβγ to this site was inhibited by an α1-binding domain of CCβ, thus providing an explanation for the functional antagonism existing between CCβ and G protein inhibition. The data do not support proposals that Gβγ inhibits α1 function by interacting with the site located in the loop I–II linker. These results define the molecular mechanism by which presynaptic G protein-coupled receptors inhibit neurotransmission.

Keywords: synaptic transmission, protein–protein interaction, signal transduction, calcium, neurosecretion

Studies on stimulation-evoked release of norepinephrine from sympathetic terminals of the cat’s nictitating membrane before and after α-adrenergic blockade led to the discovery in 1971 of an inhibitory presynaptic α adrenoreceptor, now known as one of the α2-adrenoreceptors (1). Presynaptic inhibition of neurosecretion by the released neurotransmitter (2) or by neuropeptides (3), all acting through G protein-coupled receptors, is now recognized as an important regulatory feedback mechanism utilized throughout the central and the peripheral nervous system. Evidence has accumulated to indicate that this type of inhibition of neurotransmitter release is due to inhibition of presynaptic N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels (4–9) by a mechanism that is likely to use the βγ signaling arm of activated G proteins (10, 11).

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels are multisubunit complexes formed of a pore-forming and voltage-sensing α1 subunit, a regulatory α2δ, and one or possibly two (12) regulatory β subunits. Voltage dependence; fundamental aspects of activation, deactivation, and inactivation; feedback inhibition by Ca2+; and sensitivity to various Ca2+ channel blockers are all encoded in α1 subunits, of which there are six major types (S, A, B, C, D, and E). Each is subject to modulation to variable degrees by the named regulatory subunits, and each is expressed in alternatively spliced forms (reviewed in refs. 13–15). The N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels regulated negatively by a G protein-coupled pathway involving Gβγ are encoded in the A-, B-, and E-type α1 subunits (reviewed in ref. 16). Studies carried out primarily with endocrine cells (refs. 17 and 18; reviewed in ref. 19) and, more recently with cardiomyocytes derived from a Goα knockout mouse (20), have shown that at least one subtype of L-type Ca2+ channels is also subject to inhibitory regulation by a G protein-coupled pathway. In contrast to the regulation of non-L-type Ca2+ channels by a membrane-delimited pathway, regulation of L-type Ca2+ channels by a G protein-coupled pathway is thought to depend on the intermediary activation of a phosphoprotein phosphatase and appears therefore to involve phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycle, affecting an as yet unidentified component of the Ca2+ channel (20, 21).

In addition to the “primary” regulation by β, α2δ and an activated G protein, N- and/or P/Q-type channels are further fine-tuned by a cross-talk between calcium channel β subunits (CCβs) and activated G proteins. This was shown by Dolphin and collaborators (22), who found that inhibition of Ca2+ channel currents in dorsal root ganglion cells by the GABAB agonist baclofen is enhanced in cells in which CCβ subunits had been depleted by previous injection of specific antisense oligonucleotides. This led them to propose that CCβ subunits attenuate or antagonize inhibitory regulation by G proteins.

The inhibitory regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by G protein activation seen in neurons and neuronal-type cells (refs. 4–9; for review see ref. 16) has been reconstituted by expression of cloned α1 subunits in Xenopus oocytes (23) and in mammalian cells (11). Likewise, the antagonism discovered by Dolphin and collaborators (22) between CCβ and inhibition by G protein activation (24, 25) has also been reconstituted in Xenopus oocytes, as G protein activation fails to inhibit α1A currents in oocytes coexpressing a CCβ (24, 25). These findings opened the possibility to answer questions as what is the real molecular (subunit) nature of the regulated channels, whether activated G proteins interact directly with one of the components of the Ca2+ channel complex, and, if so, with which, and whether β subunits and activated G proteins interact competitively.

In support of the proposal of Ikeda (10) and Herlitze et al. (11) that Gβγ may be acting by binding directly to one of the components of the non-L-type α1 subunits, Zamponi et al. (26) and De Waard et al. (27) discovered the existence of a Gβγ-binding activity in G protein-sensitive α1A and α1B subunits that is absent in the G protein-insensitive α1C. This binding activity is located in the cytosolic loop that connects the homologous hydrophobic repeat domains I and II (loop 1), which incidentally also contains the primary CCβ-binding site (28). De Waard et al. (27) reported further that a mutation of α1A, R387E, that interferes in vitro with Gβγ binding interfered in Xenopus oocytes with development of the inhibition by activated G protein, and they proposed that Gβγ acted to inhibit Ca2+ channel activity by binding to the loop 1 site identified through the in vitro binding studies. However, Zhang et al. (29) reported that an α1B/α1C chimera that should not have bound Gβγ exhibits a normal inhibitory response to G protein activation, and, more recently, Herlitze et al. (30) reported that α1A[R387E] expressed in HEK cells is inhibited by activated G protein. It thus appears questionable whether the Gβγ-binding site discovered by Zamponi et al. (26) and De Waard et al. (27) is indeed relevant to G protein-induced inhibition of neuronal Ca2+ currents, and, by extension, it remains to be determined whether α1 is indeed the direct target (effector) of the activated G proteins.

We have also searched for a Gβγ-binding site on an α1 subunit, but instead of working with the α1A or α1B subunit, we worked with α1E, which, like α1A and α1B, is also subject to negative regulation by G protein-coupled receptors (31). We found that Gβγ interacts with two α1E sites, which, coincidentally, colocalize with the two recently identified CCβ-binding sites (12): one is located in the loop connecting homologous repeat domains I and II (28), and the other is in the C-terminal tail. In contrast to the proposals of Zamponi et al. (26) and De Waard et al. (27), we find no evidence that the loop 1 site is involved in mediation of the inhibitory effect of activated G proteins. In contrast, all our data point to the C-terminal Gβγ-binding site as the one that mediates the action of Gβγ. In vitro binding of Gβγ to the C-terminal site is prevented by coincubation with a recombinant α1-binding CCβ fragment.

METHODS

Glutathione S-Transferase-α1E Fusion Proteins.

GST-α1E fusion plasmids were based on pGEX-4T-1 (Pharmacia) and were constructed by conventional means using either natural restriction fragments of α1 subunits or defined fragments excised by PCR. After transfection into E. coli BL21, synthesis of the fusion proteins was induced with 0.2 mM isopropylthiogalactoside (IPTG) in a liquid culture grown to OD of 1.0. After 2–3 hr at 37°C the cells were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in NETN lysis buffer (1.0 ml per 20 ml culture; NETN, 0.5% Nonidet P-40/1 mM EDTA/20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0/100 mM NaCl) and lysed by sonication. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The GST-fusion proteins in the supernatant were adsorbed to glutathione (GSH)–Agarose beads for 30 min at room temperature in NETN (1 vol lysate: 1 vol 50% (vol/vol) slurry of Agarose–GSH beads (Pharmacia) in NETN). The last wash was with binding buffer [1% vol/vol Lubrol-PX (Sigma)/2 mM EDTA/100 mM NaCl/20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0] instead of NETN.

G protein βγ dimers were purified from human or porcine erythrocyte membranes (32) and from bovine brain (33). Bovine brain Go was purified as described previously (34). 35S-labeled forms of rat β2a (35), β2a[D1–3] (β2a[1–211]), and β2a[D4] (β2a[206–415]) and β2a[D4–5] (β2a[206–604]) were synthesized in rabbit reticulocyte lysates by coupled transcription–translation (Promega) in the presence of [35S]methionine as described by Pragnell et al. (28). β2a[D1–3] and β2a[D4], each with a hexa-histidine tag at its N terminus, were synthesized in Escherichia coli (strain BL21[DE3]) fused to thioredoxin using the pET-32a(+) vector and reagents supplied in kit form by Novagen. Single colonies of transformed cells were expanded, inoculated into 100 ml of Luria–Bertani medium, grown to OD 1.0, induced with 0.4 mM IPTG for 2 h at 37°C, and harvested by centrifugation. The pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of 5 mM imidazole/500 mM NaCl/20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.9 (buffer A), sonicated, and centrifuged in the cold at 27,000 × g for 15 min. β2a[D1–3] was purified from the supernatant by Ni affinity chromatography (1-ml bed volume), followed by dialysis against 100 mM NaCl/2 mM EDTA/20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5 (buffer B). β2a[D4] was solubilized from the pellet with 10 ml of 6 M urea in buffer A (1 h at 4°C), followed by centrifugation as above. The supernatant was diluted with 1 vol of buffer A, and the protein was adsorbed onto immobilized Ni (1-ml bed volume equilibrated in buffer A containing 2 M urea). After washing the resin with 2 M urea in buffer A, the protein was eluted with 5 ml of 1 M imidazole/0.5 M NaCl/Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, containing 2 M urea. The eluate was dialyzed against buffer B with decreasing concentrations of urea, ending with an overnight dialysis against buffer B without urea, all at 4°C.

Protein–Protein Interactions.

Twenty-five percent (vol/vol) slurries of Agarose-GSH beads with approximately 1 μg of GST or GST-α1[frg] were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in a final volume of 100 μl of binding buffer (buffer B plus 1% Lubrol-PX) without or with 1 μg (20 pmol) Gβγ, 10 μl reticulocyte lysate containing 10–30 nM 35S-labeled β2a fragments, or 100–500 pmol thioredoxin-His6-β2a.frg. At the end of the incubations the beads were washed three times with 1.0 ml of binding buffer and resuspended in 15 μl of Laemmli’s 2× sample buffer. Proteins released from the beads were analyzed by 10% SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography to detect binding of [35S]β2a fragments or by Western blotting to determine binding of G protein β subunits using rabbit anti-βcommon antibodies (gifts from Suzanne Mumby and Alfred Gilman, University of Texas, Dallas, and from Guenter Schultz, University of Berlin). Rabbit IgG was revealed by ECL (Amersham).

α1 Subunit Constructs and Synthesis of cRNAs.

α1 cDNAs were wild-type (wt) α1E, α1E[1–2312], clone 239 of Schneider et al. (36); α1C[DN60], α1C[60–2171] (37), α1E[DC277], α1E[1–2035]; α1E[DC244], α1E[1–2068]; chimera EC1 (α1E with α1C C-terminal tail): α1E[1–1728]/α1C[1513–2171]; chimera EC30 (α1E with L1 of α1C): α1E[1–337]/α1C[421–583]/α1E[503–2312]. Deletion mutants and chimeras were made by standard recombinant DNA techniques using wild-type α1E and α1C[DN60] cDNAs as donor DNAs. All cDNAs were subcloned into the NcoI site of the transcription competent pAGA2 plasmid (38, 39). cRNAs were synthesized using mMessage mMachine reagents and protocols purchased in kit form from Ambion (Austin, TX). The resulting cRNAs were resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated H2O.

Xenopus Oocytes, Expression of Calcium Channels, and Electrophysiological Recordings.

Stage V and VI Xenopus laevis oocytes, isolated as described in Tareilus et al. (12) and injected with 50 nl containing 100 μg/ml each of two cRNAs: one encoding one of the α1 subunits and the other encoding the human type-2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (40), also transcribed from pAGA2. The cut-open vaseline gap voltage-clamp method of Taglialatela et al. (41), as modified (42, 43), was used throughout. The external solution had the following composition: 10 mM Ba2+/96 mM Na+/10 mM Hepes, titrated to pH 7.0 with methanesulfonic acid (CH3SO3H). The solution in contact with the oocyte interior was 110 mM K-glutamate/10 mM Hepes, titrated to pH 7.0 with KOH. Low-access resistance to the oocyte interior was obtained by permeabilizing the oocyte with 0.1% saponin. For further details see Noceti et al. (43). Currents were recorded 3–5 days after cRNA injection. Test protocols are depicted on the figures.

RESULTS

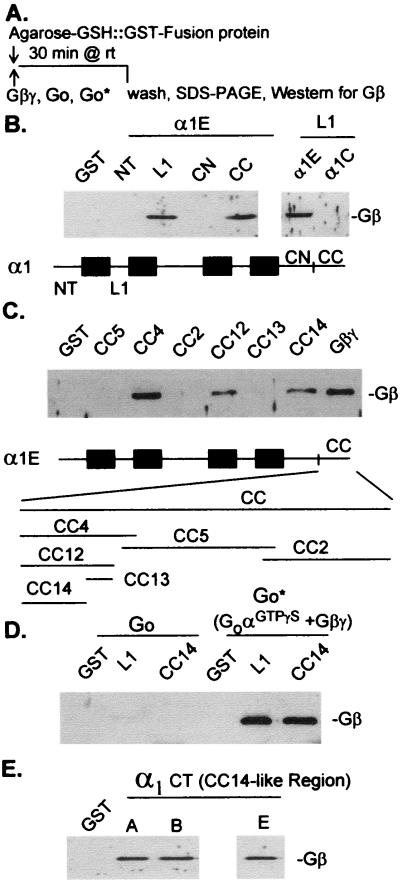

Fig. 1 shows the results from experiments in which we tested the ability of various fragments of the neuronal, G protein-sensitive α1E fused to GST and immobilized on glutathione-Agarose for their ability to bind purified bovine brain G protein βγ dimers. Of the regions tested, we found two that bound Gβγ with sufficient avidity to withstand washing: the loop connecting repeat domains I and II (L1) and the carboxyterminal half of the C-terminal tail (Fig. 1B). In agreement with the findings of Zamponi et al. (26) and DeWaard et al. (27), Gβγ bound also to the L1 regions of the G protein-sensitive α1A and α1B (not shown). Successively smaller fragments of the α1E C-terminal tail showed that the Gβγ-binding activity resides in fragment CC14, a 38-amino acid stretch located approximately in the middle of the tail (Fig. 1C). The need for free Gβγ was tested by incubating α1E[L1] and α1E[CC14] with unactivated bovine brain Go before and after its activation by GTP[γS]. Gβγ in the heterotrimeric Go did not bind to α1E fragments, but the Gβγ released from a Go by treatment with 100 μM GTS[γS] and 10 mM MgCl2 did (Fig. 1D). In other experiments we found that the α1E[CC14] region recognizes not only the bovine brain Gβγ but also Gβγ purified from human and porcine erythrocytes (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Interaction between fragments of α1E and Gβγ. Binding of Gβγ to fragments of α1 fused to GST was analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-Gβcommon antibody. The figure shows digitized pictures of autoradiograms identifying the 35-kDa Gβ subunit. Here and throughout, α1 subunits are represented as homologous hyrophobic repeat domains I–IV (boxes) connected by cytosolic loops (L1 through L3) with N-terminal (NT) and C-terminal extensions. CN, N-terminal portion of a C terminus; CC, C-terminal portion of a C terminus. α1E is represented by black repeat domains connected by heavy lines denoting N and C termini and the connecting loops; α1C is represented by open boxes connected by thin loops and flanked by thin N and C termini. (A) Outline of the experimental protocol. (B and C) Binding of Gβγ to α1 fragments. (B) NT, α1E[1–89]; L1, α1E[356–451]; CN, α1E[1712–1980]; CC, α1E[2036–2312]; α1C L1, α1C[436–554]. (C) Fragments of the CC region of α1E: CC4, α1E[2036–2136]; CC5, α1E[2122–2240]; CC2, α1E[2220–2312]; CC12, α1E[2036–2093]; CC13, α1E[2075–2093]; CC14, α1E[2036–2074]. Gβγ, 12% SDS/PAGE and Western blot of 100 ng bovine brain Gβγ. (D) Only free Gβγ interacts with L1 and CC14. Go, 200 nM purified bovine brain Go in binding buffer (see Methods); Go*, 200 nM Go after 30-min treatment at 32°C with 100 μM GTP[γS] and 10 mM MgCl2 in binding buffer. (E) Binding of Gβγ to C-terminal fragments of α1A and α1B (α1CT fragments). α1A CT, α1A[[2150–2216]; α1B CT, α1B[2013–2069]; α1E CT = CC4 or α1E[2036–2136]. All α1 fragments were fused to GST. α1 numbers correspond to the amino acids of the respective α1 subunits that make up the fragments fused to GST; numbering is according to GenBank L277450 for α1E, GenBank X15539 for α1C, GenBank X57476 for α1A, and GenBank U04999 for α1B. β2a (rat) is numbered according to GenBank M80545. In this and the other figures GST denotes incubation of Gβγ or [35S]β2a with Agarose-GSH::GST without α1 fragments fused to the GST. CC14 or α1E[2036–2073] = MERSSENTYK ARRRSYHSSL RLSAHRLNSD SGHKSDTH.

The discovery that α1E has two Gβγ-binding sites required that we search for a functional correlate that would indicate whether one, both, or neither of these sites is involved in inhibitory regulation of neuronal Ca2+ channels. To this end, α1E Ca2+ channels were expressed in Xenopus oocytes together with the M2 muscarinic receptor (M2R), which is coupled to effector functions by the Gi/Go group of G proteins, and analyzed the inhibition of Ca2+ channel currents by the muscarinic agonist carbachol (CCh). Lux and coworkers (44, 45) and Pollo et al. (46) showed that inhibition by G protein-coupled receptors is relieved by strong depolarizations, a phenomenon that has since been recapitulated in many other studies (e.g., ref. 9), including those of Ikeda (10) and Herlitze et al. (11), which point to Gβγ as the executing arm of activated G proteins. We thus tested for reconstitution of the G protein-dependent regulation in the oocyte both by eliciting the agonist-mediated reduction in current amplitude and/or by assessing the concurrent appearance of its reversal by a depolarizing prepulse.

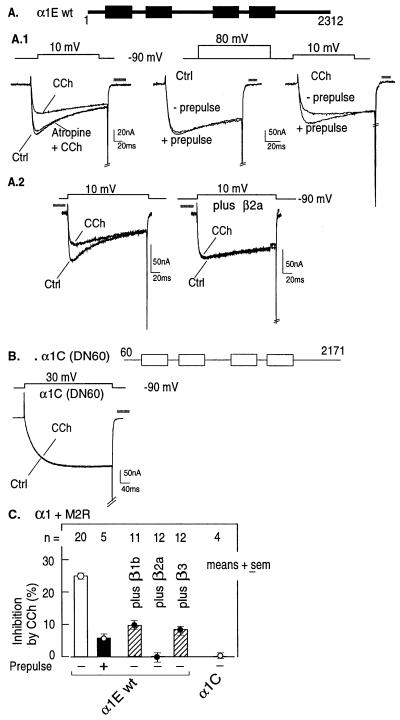

Fig. 2 illustrates the characteristics of inhibition of α1E currents triggered by M2R in Xenopus oocytes and the lack of an effect on α1C. As seen in 20 oocytes, activation of M2R with CCh reduced peak currents 25.1 ± 0.6% (mean ± SEM; Fig. 2 A and C). This inhibition was reversed by the muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine (Fig. 2A Left) and by depolarizing prepulses (Fig. 2 A.1 and C Center and Right). Coexpression of β2a interfered with muscarinic inhibition of α1E (Fig. 2A.2), and the degree of inhibition was dependent on the type of CCβ tested: β2a essentially abolished the effect of M2R, whereas β1b and β3 inhibited it by only about 50–60% (Fig. 2C). In contrast to α1E, and in agreement with previous studies (10), α1C channels failed to be inhibited by activation of a Gi/Go-coupled receptor (Fig. 2 B and C).

Figure 2.

Regulation of α1E but not α1C by a Gi/Go-coupled receptor; reversal of α1E inhibition by ligand antagonist and depolarizing prepulse and prevention by coexpression of calcium channel β2a subunit. All oocytes were injected with M2R and the indicated α1 and β subunits. (A and B) Representative records. Test protocols are shown above the current traces. (C) Summary of results. CCh was 50 μM, atropine (in the presence of CCh, was 0.5 μM. Inhibition by CCh (%) = IBa after 50 μM CCh/IBa after CCh washout × 100. IBa were measured isochronically at the peak of the control current after CCh washout. The bars represent means ± SEM of the indicated number of oocytes.

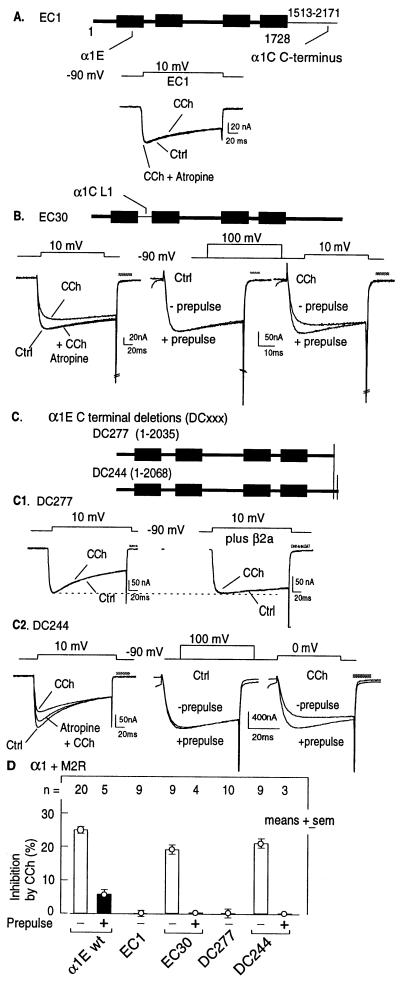

To determine which of the two Gβγ-binding sites had the potential of mediating inhibition of α1E currents, we tested two α1C/α1E chimeras. In EC30 we replaced the α1E L1 segment with that of α1C, which is unable to bind Gβγ (Fig. 1). In EC1 we replaced the complete C terminus of α1E with that of the G protein-insensitive α1C. As shown in Fig. 3, the regulation by M2R was lost in EC1, whereas it was retained in EC30. These results indicated that of the two Gβγ-binding sites discovered in the experiments of Fig. 1, only the one located in the C terminus could be of importance and that Gβγ binding to the L1 segment was not involved in the inhibitory regulation of these channels.

Figure 3.

Functional identification of a 33-aa region of α1E that confers susceptibility to regulation by a G protein-coupled receptor. All oocytes were injected with M2R and the indicated α1 cRNAs. (A) Lack of inhibition by M2R of EC1, a chimera formed of α1E with an α1C C terminus. (B) EC30, a chimera formed of α1E with an α1C L1 region, is susceptible to inhibition by M2R, and this inhibition is sensitive to a depolarizing prepulse. (C) Truncation of the C-terminal tail of α1E by 277 amino acids, α1E[1–2035] (DC277 on figure), eliminates the effect of CCh (C1), but removal of 244 amino acids, α1E[1–2068] (DC 244 on figure), does not eliminate inhibitory regulation by the G protein-coupled receptor, seen as CCh-induced reduction in activity that can be blocked either by atropine or by a depolarizing prepulse (C2). Note that the effect of β2a to slow the rate of α1E inactivation is still present in DC277. (D) Summary of effects of M2R activation on α1E/α1C chimeras and C-terminally truncated, mutated α1E constructs. α1E wild-type data are the same as in Fig. 1B.

Two α1E mutants showed that the C-terminal Gβγ-binding site is essential for responsiveness to G protein activation (Fig. 3 C and D). The inhibitory response to G protein activation was retained in α1E[DC244], an α1E that lacks its last 244 amino acids but retains 35 of the 38 amino acids that constitute the Gβγ-binding α1E[CC14] characterized in Fig. 1, whereas it was lost in α1E[DC277], an α1E that is truncated just prior to the beginning of the Gβγ-binding fragment (Fig. 3C Center and Right). In contrast to the loss of inhibitory regulation by M2R, α1E[DC277] retained full sensitivity to regulation by β2a. This was assessed by expressing α1E[DC277] alone and in combination with β2a. β2a caused (i) a slowing of the rate of inhibition by voltage (Fig. 3C), (ii) a shift in the voltage dependence for activation (data not shown), and (iii) a shift in the midpotential of inactivation (data not shown), as it does when expressed with the wild-type α1E (47).

Amino acid alignments showed that the C-terminal tails of α1B and α1A, but not the tail of α1C, contain a sequence that is homologous to the Gβγ-binding domain of α1E. Fragments containing these α1B and α1A sequences, expressed as GST-fusion proteins, were able to bind Gβγ (Fig. 1E). This indicated that not only the α1E channels but also the N-type α1B and P/Q-type α1A channels have two Gβγ-binding sites. We propose that, as is the case for α1E, Gβγ inhibits α1B and α1A also through its interaction with these C-terminal binding sites instead of the L1 sites. None of the C-terminal Gβγ-binding fragments of α1 subunits contains a QXXER motif of the type found in the Gβγ-binding domains of type-2 adenylyl cyclase (AC2), the G protein-sensitive, inwardly rectifying potassium channel (GIRK1) and the C terminus of the Gβγ-responsive β adrenergic receptor kinase (βARK) (48). Further studies are needed to better define structural features of Gβγ-binding domains.

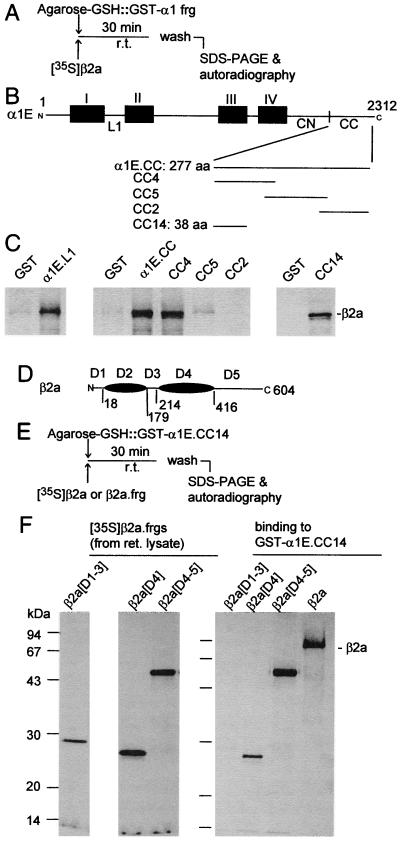

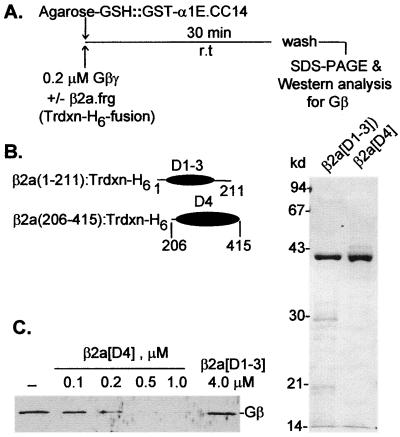

The location of the functionally relevant Gβγ-binding site in α1E is of interest, because, as mentioned above and reported recently (12), α1E has two independently identifiable binding sites for calcium channel β subunits: one is located in its L1 region as shown previously for α1A, α1B, and α1C (28), and the other is in the α1E[CC] fragment that also contains the Gβγ-binding domain. Using the strategy outlined in Fig. 4A and B, we then tested which subregion of the α1E[CC] fragment binds β2a and found it to be the same as the one that binds Gβγ (i.e., α1E[CC14]; Fig. 4C). Amino acid alignments of the four CCβ subunits defines five homology domains of which domains 1, 3, and 5 vary substantially in sequence, whereas domains 2 and 4 are highly conserved. Fig. 4 D–F shows that the portion of β2a that binds to α1E[CC14] is β2a[206–415]. This corresponds to its homology domain 4 (D4) and is the same region of CCβ subunits that interacts with the L1 segments of α1 subunits (49). Given the functional antagonism between Gβγ and CCβ (refs. 22, 24, and 25; see also Fig. 2 A.2), we tested whether binding of one interferes with that of the other. For this purpose we synthesized in E. coli and purified several fragments of β2a. Two that contained domain 4 of β2a (β2a[D4] and β2a[D4–5]) bound to α1E[CC14]; one that did not contain this domain, i.e., β2a[D1–3], did not bind to the C-terminal Gβγ-binding domain of α1E (Fig. 4 D–F). β2a[D4] was then used to test for its ability to interfere with the binding of Gβγ to α1E[CC14] fused to GST (Fig. 5). Binding of Gβγ was monitored by Western blotting after elution from the immobilized α1E[CC14]. As shown in Fig. 5C, β2a[D4] prevented binding of Gβγ α1E[CC14] in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas β2a[D1–3] did not.

Figure 4.

CC14 (α1E[2036–2074]), the C-terminal Gβγ-binding domain of α1E, is also a CCβ-binding domain, and CCβ2a[206–412] contains the α1-binding domain of CCβ2a. (A–C) Localization of a β2a-binding site within the α1E C terminus. (A) Outline of experiment. (B) Ideogram of α1E and α1E fragments tested as GST fusions for β2a-binding activity. (C) Binding of [35S]β2a to the fragments shown in B. CC, CC2, CC4, CC5, and CC14 are the same as in Fig. 1. (D–F) Binding of β2a fragments to α1E[CC14]. (D) Ideogram of β2a. Shown are the five homology domains: D1, β2a[1–17]); D2, β2a[18–178]; D3, β2a[179–213]; D4, β2a[214–415]; and D5, β2a[415–604], of which the D2 and D4 domains are defined by their high, ca. 75% sequence conservation among the type 1, 2, 3, and 4 calcium channel β subunits. Numbers correspond to amino acid positions at domain interfaces. (E) Outline of experiment. (F) SDS/PAGE and autoradiograms of 35S-labeled β2a fragments synthesized by reticulocyte lysates (Left and Center) and binding to α1E[CC14] fused to GST.

Figure 5.

Occlusion of the Gβγ-binding site by β2a[D4], the α1-binding domain of, but not by, D1-D3 of β2a. (A) Outline of experiment. (B) Scheme of the structure of β2a[D1-D3] and β2a[D4] fusion proteins used and SDS/PAGE analysis of the purified fusion proteins. Fusion proteins were visualized by Coomassie blue staining. (C) Inhibition of Gβγ binding to α1E[CC14] by increasing concentrations of the recombinant β2a[D4], but not by the recombinant β2a[D1-D3]. Gβ was visualized by Western blot analysis as in Fig. 1.

DISCUSSION

Taken together our experiments show that the molecular determinant that confers to α1E the sensitivity to regulation by a G protein-coupled pathway resides in a short stretch of only 38 amino acids (α1E[CC14]). A sequence homologous to α1E[CC14] is present also in α1B and α1A Ca2+ channels, and both bind Gβγ (Fig. 1D).

Our data show further that Gβγ reduces macroscopic currents of α1E by interacting with a site that is also seen by a stimulatory CCβ subunit. One mechanism by which Gβγ could be acting could have been by merely displacing a stimulatory β from its site. In this case, inhibition would have been the expression of a loss of β function. Given that the Gβγ-insensitive α1E[DC277] retains all known regulations by β2a, this is not a likely mechanism. A different mechanism by which Gβγ might be acting is by enhancing an intrinsic inhibitory activity of the C terminus. In support of this possibility, in the case of α1C channels, removal of 2/3 of its C terminus leads to an increase in channel activity due to an increase in the channel’s Po, which is suggestive of existence of an intrinsic C terminus-mediated autoinhibitory activity (50). Studies of single-channel kinetics will be necessary to elucidate the biophysical nature of the changes induced in α1E channels by Gβγ.

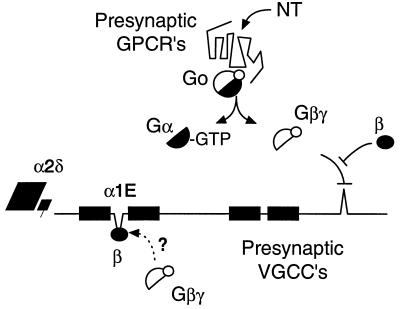

In summary we provide proof for direct interaction of Gβγ with two sites of the α1 subunit of a neuronal, non-L-type Ca2+ channel and for the functional relevance of one but not the other of these sites. In addition, as shown in Fig. 5 and summarized in the model of Fig. 6, we showed the existence of direct antagonism between the binding of inhibitory Gβγ and that of a stimulatory CCβ subunit. Our results and conclusions stand in contrast to those of Zamponi et al. (26) and De Waard et al. (27), who have proposed the L1 Gβγ-binding site as the site responsible for mediation of inhibition by Gβγ. However, an analysis of their data shows that their conclusions were not based on unique interpretations of their data. Thus, Zamponi et al. (26) established only that L1 sequences that bind Gβγ can inhibit G protein regulation of α1B. This result could also have been obtained with other Gβγ-scavenging compounds whether or not they were derived from α1. De Waard et al. (27), on the other hand, probed for a role of the L1-binding site by testing the effect of a point mutation that abolished Gβγ binding in vitro. But they did so using oocytes that were inhibited by G protein activation by only 12.6%, making it difficult to assess an effect of the mutation on inhibition of peak currents. Although De Waard et al. (27) attempted to circumvent this shortcoming in the assay system by measuring changes in kinetics (time to peak) and indeed seem to have observed the expected loss of an effect of G protein activation, studies by others (29, 30) have shown that the same mutation (QQIER to QQIEE) does not interfere with the inhibitory effect of Gβγ. Our conclusion that the L1 site is not required for inhibition of the channel by Gβγ is based on the assessment of the unaltered regulation of EC30 by G protein activation, which is present even though this chimera carries an L1 loop that does not bind Gβγ. It is worth noting that Zhang et al. (29) tested an α1B/α1C chimera equivalent to our EC30 and also found that it retained regulation by G protein activation.

Figure 6.

Model of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) regulated by protein–protein interactions defined in this report. The channels are envisioned as α1.β.α2δ heterotetramers regulated negatively by free Gβγ formed upon activation of a G protein of the Gi/Go family. This occurs in response to stimulation of presynaptic G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) by the released neurotransmitter (NT) or by neuromodulatory peptides that are either coreleased with the neurotransmitter or released by neighboring neurons. The action of free Gβγ can in turn be prevented by a Ca2+channel β subunit (CCβ). Note that the function of the Gβγ-binding site in L1 is unknown, and also that, although CCβ inhibition of the inhibitory effect of Gβγ is likely to be due to competitive displacement of Gβγ from its C-terminal binding site, we have not ruled out the possibility that CCβ interferes additionally by binding to Gβγ.

The complete description of the biochemical pathway by which G protein-coupled receptors inhibit neurotransmission is now possible: neurotransmitter binds to the receptor, the receptor catalyzes the activation of a G protein, this results in GTP binding followed by dissociation of the trimeric protein into an α-GTP complex and a βγ dimer, and, as surmised from intact cell studies by Ikeda (10) and Herlitze et al. (11), the Gβγ dimer proceeds to inhibit Ca2+ channel activation by the incoming action potential through direct interaction with its α1 subunit. This inhibition can account for the potentiation of stimulus-evoked noradrenaline release from sympathetic terminals reported by Langer and Vogt (1) 25 years ago when they treated the synapses with phenoxybenzamine, an alkylating agent that irreversibly blocks α-adrenergic receptors. Likewise, this mechanism also explains the pertussis toxin-sensitive and, thus, Gi/Go-mediated inhibition by both carbachol and morphine of the depolarization-evoked release of acetylcholine from rat myenteric plexus neurons (51).

Depending on the type of β subunit that colocalizes with α1, and also on the type of α1 subunit, it is possible to envision fine tuning of the inhibition by Gβγ to the extent that it may be extremely potent, as shown for inhibition of K+-induced neurotransmitter release from cerebral cortex slices by opioids (3), or be very subtle and even absent. The G protein activated by receptor at the presynaptic terminal is likely to be Go (reviewed in ref. 16).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants DK19318 and AR43411 to L.B. and A.R. and 38970 to E.S., by an American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid to R.O., and National Institutes of Health National Research Service Award GM 17120 and an American Heart Association Scientist Development grant to N.Q.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CCβ

calcium channel β subunit

- CCh

carbachol

- Gβγ

G protein βγ dimer

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- M2R

type-2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor

- VGCC

voltage-gated calcium channel

References

- 1.Langer S Z, Vogt M. J Physiol (London) 1971;214:159–171. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langer S Z, Adler-Graschinsky E, Giorgi O. Nature (London) 1977;265:648–650. doi: 10.1038/265648a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arbilla S, Langer S Z. Nature (London) 1978;271:559–560. doi: 10.1038/271559a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bean B P. Nature (London) 1989;340:153–156. doi: 10.1038/340153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipscombe D, Kongsamut S, Tsien R W. Nature (London) 1989;340:639–642. doi: 10.1038/340639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunlap K, Fischbach G D. J Physiol (London) 1981;317:519–535. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsunoo A, Yoshii M, Narahashi T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9832–9836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seward E, Hammond C, Henderson G. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1991;244:129–135. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAllister-Williams R H, Kelly J S. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1491–1506. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00131-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeda S. Nature (London) 1996;380:255–258. doi: 10.1038/380255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herlitze S, Garcia D E, Mackie K, Hille B, Scheuer T, Catterall W A. Nature (London) 1996;380:258–262. doi: 10.1038/380258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tareilus E, Roux M, Qin N, Olcese R, Zou J, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12703–12708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birnbaumer L, Campbell K P, Catterall W A, Harpold M M, Hofmann F, Horne W A, Mori Y, Schwartz A, Snutch T P, Tanabe T, Tsien R W. Neuron. 1994;13:505–506. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perez-Reyes E, Schneider T. Kidney Int. 1995;48:1111–1121. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunlap K, Luebke J I, Turner T J. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolphin A C. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:35–43. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)81865-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleuss C, Scherübl H, Hescheler J, Schultz G, Wittig B. Nature (London) 1992;358:424–426. doi: 10.1038/358424a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen C, Clarke I J. J Physiol (London) 1996;491:21–29. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider T, Igelmund P, Hescheler J. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:8–11. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(96)01001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venzuela D, Han X, Mende U, Fankhauser C, Mashimo H, Huang H, Pfeffer J, Neer E J, Fishman M C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1727–1732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armstrong D L, White R E. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:403–408. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90192-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell V, Berrow N S, Fitzgerald E M, Brickley K, Dolphin A C. J Physiol (London) 1995;485:365–372. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaneko S, Fukuda K, Yada N, Akaike A, Mori Y, Satoh M. NeuroReport. 1994;5:2506–2508. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199412000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roche J P, Anantharam V, Treistman S N. FEBS Lett. 1995;371:43–46. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00860-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bourinet E, Soong T W, Stea A, Snutch T P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1486–1491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zamponi C N, Nargeot J, Snutch T P. Nature (London) 1997;385:442–446. doi: 10.1038/385442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Waard M, Liu H, Walker D, Scott V F S, Gurnett C A, Campbell K P. Nature (London) 1997;385:446–450. doi: 10.1038/385446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pragnell M, De Waard M, Mori Y, Tanabe T, Snutch T, Campbell K P. Nature (London) 1994;368:67. doi: 10.1038/368067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J F, Ellinor P T, Aldrich R W, Tsien R W. Neuron. 1996;17:991–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herlitze S, Hockerman G H, Scheuer T, Catterall W A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1512–1516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olcese R, Ottolia M, Qin N, Platano D, Birnbaumer M, Toro L, Birnbaumer L, Stefani E. Biophys J. 1997;72:A145. (abstr.). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Codina J, Rosenthal W, Hildebrandt J D, Birnbaumer L, Sekura R D. Methods Enzymol. 1985;109:446–468. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(85)09108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Codina J, Birnbaumer L. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29339–29342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Dongen A, Codina J, Olate J, Mattera R, Joho R, Birnbaumer L, Brown A M. Science. 1988;242:1433–1437. doi: 10.1126/science.3144040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perez-Reyes E, Castellano A, Kim H S, Bertrand P, Baggstrom E, Lacerda A E, Wei X, Birnbaumer L. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1792–1797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider T, Wei X, Olcese R, Constantin J, Neely A, Palade P, Perez-Reyes E, Qin N, Zhou J, Crawford G D, Smith G R, Appel S H, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. Recept Channels. 1994;2:255–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei X, Neely A, Olcese R, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. Recept Channels. 1997;4:205–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanford J, Codina J, Birnbaumer L. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:9570–9579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei X, Perez-Reyes E, Lacerda A E, Schuster G, Birnbaumer L, Brown A M. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21943–21947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peralta E G, Ashkenazi A, Winslow J W, Smith D H, Ramachandran J, Capon D J. EMBO J. 1987;6:3923–3929. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taglialatela M, Toro L, Stefani E. Biophys J. 1992;61:78–82. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81817-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neely A, Olcese R, Wei X, Birnbaumer L, Stefani E. Biophys J. 1994;66:1895–1903. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80983-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noceti F, Baldelli P, Wei X, Qin N, Toro L, Birnbaumer L, Stefani E. J Gen Physiol. 1996;108:143–156. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.3.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marchetti C, Carbone E, Lux H D. Pflügers Arch. 1986;406:104–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00586670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grassi F, Lux H D. Neurosci Lett. 1989;105:113–119. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pollo A, Lovallo M, Sher E, Carbone E. Pflügers Arch. 1992;422:75–83. doi: 10.1007/BF00381516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olcese R, Qin N, Neely A, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. Neuron. 1994;13:1433–1438. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen J, DeVivo M, Dingus J, Harry A, Li J, Sui J, Carty D J, Blank J L, Exton J H, Stoffel R H, Inglese J, Lefkowitz R J, Logothetis D E, Hildebrandt J D, Iyengar R. Science. 1995;268:1166–1169. doi: 10.1126/science.7761832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waard M D, Pragnell M, Campbell K. Neuron. 1994;13:495–503. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei X, Perez-Reyes E, Lacerda A E, Schuster G, Birnbaumer L, Brown A M. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21943–21947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dolezal V, Tucek S, Hynie S. Eur J Neurosci. 1986;1:127–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1989.tb00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]