Abstract

A gene homologous to methionine sulfoxide reductase (msrA) was identified as the predicted ORF (cosmid 9379) in chromosome V of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encoding a protein of 184 amino acids. The corresponding protein has been expressed in Escherichia coli and purified to homogeneity. The recombinant yeast MsrA possessed the same substrate specificity as the other known MsrA enzymes from mammalian and bacterial cells. Interruption of the yeast gene resulted in a null mutant, ΔmsrA::URA3 strain, which totally lost its cellular MsrA activity and was shown to be more sensitive to oxidative stress in comparison to its wild-type parent strain. Furthermore, high levels of free and protein-bound methionine sulfoxide were detected in extracts of msrA mutant cells relative to their wild-type parent cells, under various oxidative stresses. These findings show that MsrA is responsible for the reduction of methionine sulfoxide in vivo as well as in vitro in eukaryotic cells. Also, the results support the proposition that MsrA possess an antioxidant function. The ability of MsrA to repair oxidative damage in vivo may be of singular importance if methionine residues serve as antioxidants.

Methionine (Met) oxidation is mediated by various biological oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals, ozone, peroxynitrite, and hypochlorite, as well as by metal catalyzed oxidation systems. Peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase (MsrA) is capable of reducing either free methionine sulfoxide [Met(O)] or protein-bound Met(O) to Met, in vitro (1). Recently, the mammalian msrA cDNA has been cloned (1) and its protein has been shown to be highly expressed in renal medulla, retinal pigmented epithelial cells (RPE), blood, and alveolar macrophages (2). Both macrophages and RPE cells have the abilities to produce oxidants (3, 4), and their high level of MsrA is probably maintained to provide an efficient mechanism for restoration of intracellular Met(O) to Met. In addition to its role in repairing oxidative Met damage to protein, the MsrA in kidney may perform a salvage function by converting the Met(O) to Met and thereby sparing the need for replacement of Met lost by oxidative processes. An Escherichia coli msr A null mutant has been shown to be more sensitive to oxidative stress caused by hydrogen peroxide than the parent strain (5). It has been suggested that MsrA repairs oxidative damage to Met that occurs in vivo. This function of MsrA in vivo has special importance if Met residues act as endogenous antioxidants as proposed by Levine et al. (6).

In this study we use Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model for oxidative stress in a eukaryotic system. First, the yeast msrA gene has been cloned and overexpressed in E. coli and the resulting recombinant protein has been characterized. Then, a yeast null msrA mutant has been made and its growth and its cellular pool of Met(O) have been monitored relative to the parent strain under various culture conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The compound 2,2-azobis-(2-amidino-propane) dihydrochloride (AAPH) was purchased from Wako Chemicals (Richmond, VA). Hydrogen peroxide was purchased from Fisher. Dabsyl-chloride was purchased from Pierce.

S. cerevisiae Peptide Met(O) Reductase: Cloning and Overexpression.

Searching GenBank for a yeast homologue to the bovine msrA cDNA (GenBank accession no. U37150) revealed an ORF of 552 bp that had 32% identity over its whole length to the cDNA sequence of the bovine msrA (GenBank accession no. U18796, cosmid 9379, denoted as a homologue of pilB). This ORF was amplified by PCR using S. cerevisiae DNA as template, a 5′ sense primer (H1) containing a BamHI site (5′-CTGGAGGGATCCATGGCTGTCGCTGCCAAC), and a 3′ reverse complement primer (H2) with HindIII site (H2: 5′-AGGGCAAAGCTTCTAAAAAAGCTACATTTC). PCR was performed for one cycle of 5 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 sec at 94°C, 60 sec at 50°C, and 90 sec at 72°C. Both the amplified product and pQE-30 (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) were digested with BamHI and HindIII, and the PCR fragment encompassing the complete yeast msrA coding region was ligated into the restricted pQE-30 by using T4 DNA ligase (Boehringer Mannheim). E. coli cells (M15) were transformed with an aliquot of the ligation mixture and grown in Luria–Bertani medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and kanamycin (25 μg/ml). When cells reached an A600 of 0.8, isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and the growth continued for an additional 5 hr. The cells were harvest by centrifugation and resuspended in 50 mM Na-phosphate (pH 8.0) and 300 mM NaCl (buffer A), and sonicated. The lysate was centrifuged, the supernatant was applied to Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen), and following extensive washing with buffer A, the protein was eluted with buffer A containing 400 mM imidazole. The purity of the protein was analyzed by SDS/PAGE.

Disruption of msr A Gene in Yeast Cells.

The disruption of msrA was performed according to the procedure developed by H. Nelson and N. Nelson (personal communication). The msrA gene was interrupted by insertion of URA3 gene in the middle of the gene after a small deletion, as follows. The marker gene (URA3) was cloned in the HindIII site in pBluescript and amplified by PCR using the T3 and T7 primers. One pair of primers, A1 and A2, were made at the 3′ end of the N-terminal piece of the msrA gene and 5′ end of the C-terminal piece, respectively, each containing a specific part of A1 or A2 fused with the complement sequence of T3 and T7, respectively. The latter pair is used with H1 and H2 in the first set of PCRs to produce the N-terminal and C-terminal pieces of the msrA gene as follows: (i) PCR containing H1 + A1 primers with the msrA gene which resulted in the N-terminal piece; and (ii) PCR containing H2 + A2 primers with the msrA gene which resulted in the C-terminal piece. The second set of PCRs were as follows: (i) PCR containing the H1 + T7 primers with the URA3 gene and the N-terminal piece which resulted in the N-terminal piece fused to the URA3 gene; and (ii) PCR containing H2 + T3 primers with the URA3 gene and the C-terminal piece which resulted in the C-terminal piece fused to the URA3 gene. The third PCR consisted of H1 + H2 primers with the products of the second PCR set which resulted in the final construct: N terminus msrA + URA3 + C-terminal msrA (MUM). This construct was used for yeast transformation.

All PCRs were performed as above, and the sequences of the T7, T3, A1, and A2 primers are as follows: T3, ATTAACCCTCACTAAAG; T7, AATACGACTCACTATAG; A1, TTCCCTTTAGTGAGGGTTAATGGATACTTGTAAAACCTCCGC; and A2, GCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTGAATCCATGATCCTACTAC.

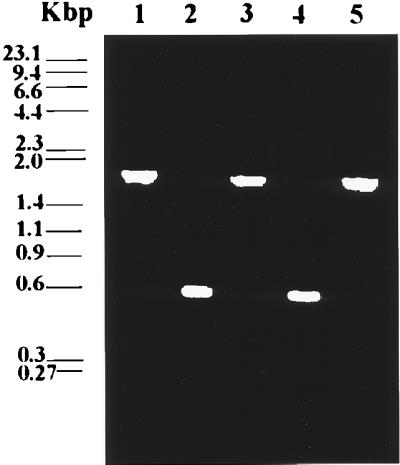

Yeast Strains and Analysis of Mutants.

S. cerevisiae haploid strains H8 (Mata ura3–52 his5) and H9 (Matα ura3–52 his6 leu2) were the original strains used in this study. These strains were a gift from Alan Hinnebusch (National Institutes of Health). Both strains were transformed with the final PCR product (MUM) by the lithium acetate method (7), and were grown on minimal media plates containing 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% dextrose, 2% agar, and the appropriate nutritional requirements without uracil. Several colonies were collected and grown on minimal medium without uracil, genomic DNA was isolated from the different transformants, and the presence of disrupted msrA gene was assayed by PCR. As shown in Fig. 2, the expected fragments of ≈550 bp (msrA gene) in wild types and 1,800 bp (≈550 bp of the msrA gene plus ≈1,250 bp of the URA3 gene) in the ura-disrupted mutants appeared following agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR products. The msrA activity in the different yeat strains was assayed as described below.

Figure 2.

Interruption of the msrA gene in yeast cells. Haploid strains H8 and H9 were transformed with a DNA fragment containing the disrupted msrA gene by the URA3 gene insertion. The cells were grown on minimal medium plates without uracil. Several colonies were collected and grown on minimal liquid medium without uracil. DNA was isolated from the different transformants, and the presence of disrupted msrA gene was assayed by PCR. PCR products are shown in the agarose gel, using oligonucleotides H1 and H2, of the wild-type and the disruptant strains and the original DNA construct used for the disruption of the gene. Lanes: 1, DNA fragment used for the interruption of the gene; 2 and 4, PCR product of DNA isolated from H8 and H9 wild-type cells, respectively; 3 and 5, PCR product of DNA isolated from msrA disruptant cells of H8 and H9 strains, respectively.

Determination of MsrA Activity.

The ability of Met(O) reductase to reduce free Met(O) was assayed by using [3H]Met(O) as substrate, prepared as described by Brot et al. (8). The reaction mixture (30 μl) contained 15 mM DTT, 25 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 16.7 μM of [3H]Met(O), and yeast extract or pure MsrA. Following incubation at 37°C the reaction was stopped by adding 0.33 mM of Met(O), and conversion of [3H]Met(O) to [3H]Met was analyzed by thin-layer chromatography on a silica gel plate using the solvent n-butanol/acetic acid/water (60:12:25). After ninhydrin treatment of the plate, the spot that corresponded to the migration of Met was extracted by water and the radioactivity was measured. The reduction of protein-bound Met(O) by MsrA was assayed using either N-acetyl[3H]Met(O) (8) or dabsyl-Met(O) (9) as substrate. In the latter assay the amino group of the Met(O) had been derivatized with dabsyl chloride (4-N,N-dimethylaminoazobenzene-4′-sulfonyl chloride). Reduction of the dabsyl-Met(O) to dabsyl-Met was determined by means of an HPLC technique. Reaction mixtures (100 μl) containing 20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 30 mM KCl, 20 mM DTT, 1 μM dabsyl-Met(O), and an aliquot of purified MsrA or yeast extract were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and stopped by the addition of 200 μl acetonitrile. After centrifugation for 5 min (top speed in a Beckman Microfuge 12 centrifuge), 10 μl of the clear supernatant solution was injected onto a 10-cm C18 column (Apex, Jones Chromatography, Denver, CO) equilibrated at 50°C with buffer [0.14 M sodium acetate, 0.5 ml/liter triethylamine (pH 6.1)] containing 30% acetonitrile. Using a linear gradient from 30 to 70% acetonitrile over 11 min the dabsyl-Met(O) was eluted at 2.6 min whereas the dabsyl-Met was eluted at 5.0 min, as monitored by peak integration at 436 nm (1 pmol of dabsyl-Met gives 340 area units). The column is washed for 5 min with the solvent containing 70% acetonitrile and re-equilibrated at 30% before the next injection. The dabsyl-Met(O) was prepared by reacting an aqueous solution of Met(O) in 100 mM bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.0) with dabsyl-chloride in acetonitrile. After 10 min at 70°C, the dabsyl-Met(O) was purified from the reaction mixture by passage through a silica gel column and step-wise elution with aqueous solutions of methanol and methanol-acetonitrile. Purity of the eluates were checked by thin-layer chromatography on silica gel plates using the solvent n-butanol/acetic acid/water (60:12:25). The dabsyl-Met(O) was collected by evaporating the solvent and stored at room temperature. For measuring MsrA activity in yeast the cells were disrupted in 25 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5) in a French pressure cell.

Determination of Met(O) in Yeast Extracts.

Yeast cells were grown aerobically in synthetic complete medium at 30°C with or without H2O2 (1 mM) or AAPH (6 mM). When cell density reached 300 Klett units (turbidity measured in a Klett–Summerson colorimeter at 540 nm) cells were spun down and washed five times with PBS prior to their disruption in French pressure cell in buffer B [6 M guanidine chloride/500 mM K-phosphate (pH 2.5)]. Following centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min the supernatant solutions were passed through microconcentrators (microcon 3; Amicon). In each case, the flow-through was collected for free amino acid analysis whereas the retained material was kept for protein bound amino acid analysis, after extensive washing with buffer B. The protein moiety of each preparation was subjected to CNBr cleavage as described to quantitate the oxidized Met (6). CNBr cleaves peptide bonds on the carboxyl side of Met [but not of such bonds involving Met(O)] to yield homoserine (10). Hydrogen chloride hydrolysis and amino acid analysis were carried out on samples with and without CNBr treatment, as described (11).

RESULTS

Isolation of the Yeast msrA Gene and Expression, Purification, and Characterization of the Recombinant MsrA Protein.

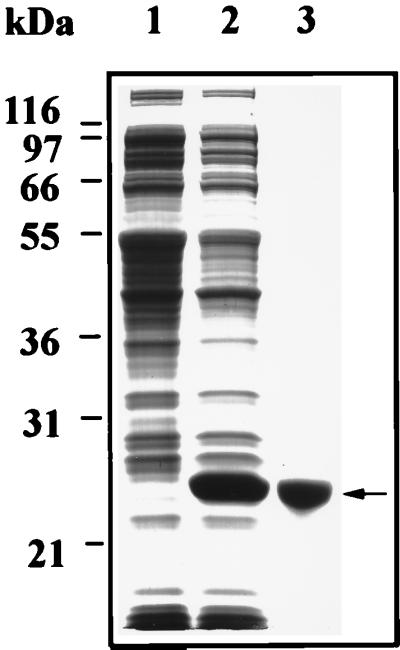

The yeast msrA gene was cloned by PCR method from yeast genomic DNA using the sequence at chromosome 5 (GenBank accession no. U18796). An ORF of 184 amino acids (calculated molecular mass of 21,140 Da) showed high homology (≈40%) to the pilB sequence that had been shown to be the msrA of Neisseria gonorrhoeae (12). The corresponding protein was overexpressed in E. coli and purified to homogeneity (Fig. 1). The ability of this protein to reduce protein-bound Met(O) and free Met(O) to Met was investigated by using dabsyl-Met(O) or N-acetyl-Met(O) and free Met(O) as substrate, respectively. The recombinant protein was found to reduce both classes of substrates as shown in Table 1. These results confirmed that the yeast homologue to pil B is actually the yeast msrA.

Figure 1.

SDS/PAGE analysis of fractions during the purification of recombinant yeast MsrA protein. M15 cells were transformed with pQE-30 harboring the yeast msrA gene and the expressed protein was purified as described. Lanes: 1, S-30 − IPTG; 2, S-30 + IPTG; 3, yeast MsrA protein eluted from the Ni-NTA resin after treatment with buffer A containing 400 mM imidazole. The arrow indicates where MsrA migrates.

Table 1.

Methionine sulfoxide reductase (MsrA) activity

| Enzyme | Specific activity, pmol/min/mg protein

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Dabsyl-Met(O) | l-(3H) Met(O) | |

| Recombinant yeast MsrA | 43,074 | 4,256 |

| Extract of yeast parent strain | 68 | 15 |

| Extract of yeast msrA mutant | 0 | 5 |

The MsrA activity was determined as described. The results for the yeast extracts represent both the H8 and H9 strains and their msrA–null mutants, respectively. Similar results to the activities shown with the dabsyl-Met(O) substrate were obtained with N-actyl-Met(O) (data not shown).

Analysis of MsrA Activity in Yeast msrA Null Mutants and Their Parent Strains.

To investigate the effects of oxidative stress on yeast cells lacking the msrA gene, a yeast null mutant of msrA was constructed as described. To confirm that these yeast strains were indeed msrA null mutants, their extracts were assayed for msrA activity. As shown in Table 1, the msrA mutant strains lost their ability to reduce protein-bound Met(O) and retained only ≈33% of their activity toward free Met(O) relative to their parent strains (Fig. 2). In addition, rabbit antibodies raised against the recombinant yeast MsrA protein showed no immunological cross reactivity with cell extracts of ΔmsrA::URA3 null mutants (data not shown).

Effect of Oxidative Stress on Growth and Met(O) Accumulation.

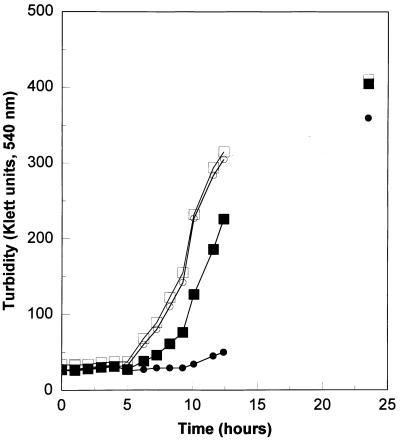

Under normal growth conditions, the ΔmsrA::URA3 mutant and its parent strain exhibited similar growth pattern. After a lag of about 5 hr both strains grew at identical rates (Fig. 3). However, in the presence of H2O2 growth of the parental strain was only slightly delayed (1–2 hr), whereas growth of the msrA mutant was delayed for an additional 4–5 hr. Similar results were obtained with the H8 strain and its msrA mutant (data not shown). In contrast, when the radical-generating compound AAPH was added to the growth medium, the growth of the msrA mutant was only slightly retarded relative to the wild-type cells (data not shown). In each case the cells were harvested when the culture reached a density of 300 Klett units. Following extensive washing the cells were resuspended in buffer B and extracts were made by passage through a French pressure cell. Amino acid composition of the protein moiety and the free amino acid content in each extract was determined.

Figure 3.

Growth of yeast strains in the presence and absence of H2O2. Yeast from stationary phase cultures were inoculated into yeast synthetic medium at 1:300 dilution and were grown aerobically at 30°C with or without H2O2 (1 mM). The symbols are defined as follows: wild-type parent strain (H9) grown with (▪) or without (□) H2O2; and H9 ΔmsrA::URA3 strain grown with (•) or without (○) H2O2.

Oxidation of Protein Met Residues.

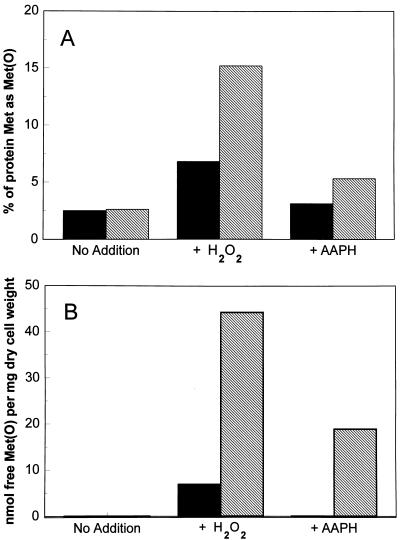

As shown in Fig. 4A, under normal conditions the Met(O) accounted for only 2.5% of the total protein Met [Met(O) + Met]. However, after growth in the presence of H2O2 Met(O) accounts for 7.5% and 15% of the total protein Met residues in the H9 and its msrA null mutant, respectively. The treatment with AAPH resulted in a similar pattern but the level of Met(O) was lower, accounting for only 3% and 5% in the H9 and H9ΔmsrA::URA3 cells, respectively. These results show that the msrA null mutant of yeast is about twice as sensitive to oxidation of protein-bound Met than is the wild-type parent strain under the oxidative stress conditions examined. It is also evident that hydrogen peroxide is more potent than AAPH in causing Met oxidation in proteins, in vivo.

Figure 4.

Met(O) content in yeast strains that were grown under different oxidative stress conditions. Each yeast strain was generally grown in a synthetic medium as described in Fig. 3 until the cell density reached 300 Klett units under each culture condition. Then cells were harvested and their extracts were measured for protein-bound Met(O) (A) or free Met(O) (B), as described. Filled bars represent wild-type (H9) strain and hatched bars represent H9 ΔmsrA::URA3 strain. Similar results were obtained with the H8 yeast strain and its corresponding null msrA mutant strain. H2O2 and AAPH concentrations were 1 mM and 6 mM, respectively.

Oxidation of Free Met.

The difference between the wild-type and the mutant msrA yeast strains, in regard to Met oxidation, was much more pronounced when the content of free Met(O) was measured in these cells under the same conditions as described above. As shown in Fig. 4B, under normal culture conditions without addition of oxidants, no free Met(O) was detected in either the msrA mutant or its parent yeast strain. In contrast, the highest value of free Met(O) (nmol/mg dry weight) was detected in the msrA mutant strain when H2O2 was added to the culture medium. Also, the ratio of free Met(O) in the msrA mutant to its parent wild-type strain was ≈7:1 under these conditions (Fig. 4B), which was about 3-fold higher than the ratio observed with the protein Met(O) (Fig. 4A). When AAPH was used to induce oxidative stress the amount of free Met(O) in the msrA mutant was much lower than that obtained with H2O2, and no free Met(O) was detected in the wild-type strain (Fig. 4B). These results clearly show that Met(O) accumulated in proteins as well as in the free amino acid pool of the yeast strain lacking the msrA gene.

DISCUSSION

In this study we describe the cloning and disruption of the yeast msrA gene. The cloned yeast gene had high homology (≈30–40% identity) to previously described msrA genes from E. coli (5), Bos tauros (1), N. gonorrhoeae (12), and Streptococcus pneumoniae (12). The overexpression and purification of the yeast MsrA in E. coli resulted in an ≈24 kDa (Fig. 1) protein by analysis on an SDS/PAGE. The molecular mass of the recombinant MsrA was slightly higher than the predicted ≈21-kDa protein, partly attributable to the six histidine residues fused to its N terminus. In general, the characteristics of the yeast MsrA enzyme activities toward Met(O) were the same as that from cow and E. coli. Like the previously described enzymes, the yeast MsrA can reduce Met(O) to Met either in its protein-bound or free form (Table 1). In addition, extract of yeast msrA null mutant showed no reducing activity toward N terminus blocked Met(O) while retaining only ≈33% of the activity toward free Met(O) in comparison to the extracts of its parent strain. These results are in agreement with previous results obtained with the E. coli msrA null mutant (5). In yeast as in E. coli, there are at least two Met(O) reductases, one (MsrA) is able to reduce both free and protein-bound Met(O) and the other that can reduce only free Met(O).

In the upstream region of the msrA ORF (ATG 17177 at chromosome V), three sequences containing the TATA box motif have been identified. One (TATA) starting at −42, and the other two (CATATATA) at positions −72 and −114, respectively. These sequences could be the binding sites for RNA polymerase or other transcription factors. Further study is needed to establish the function of these sites.

It is evident from the growth patterns that the yeast msrA mutant is more severely inhibited by H2O2 treatment than the wild-type parent strain (Fig. 3). In contrast, the msrA mutant and wild-type strains of yeast are almost equally susceptible to growth inhibition by AAPH (data not shown). The differential effect of H2O2 and AAPH on growth of mutant and wild-type strains may reflect difference in their specificity for amino acid residue oxidation. H2O2 has little ability to directly oxidize amino acid residue other than Met or Cys residues. However, in addition to Met and Cys, free radicals (ROO⋅, RO⋅) formed in the decomposition of AAPH (13) can also oxidize tryptophan, tyrosin, phenylalanine, and histidine residues in proteins (Y. Ma and E.R.S., unpublished results). This could explain why growth of the msrA mutant is more susceptible to inhibition by H2O2 than is the wild type. MsrA can repair growth-limiting oxidation of Met residues in the presence of H2O2 but cannot repair damage to other amino acids residues that limit growth in the presence of AAPH. Nevertheless, exposure of yeast to either H2O2 or AAPH leads to a substantial increase in the cellular levels of both free and protein bound Met(O). However, in all cases the increasing levels of Met(O) in msrA mutants are considerably greater than in the parent wild-type strains (Fig. 4). From these results it is clear that free and protein-bound Met(O) are substrates for the MsrA enzyme in vivo.

The oxidative stress-induced increase in free Met(O) is likely due to both an increase in the rate of free Met oxidation and the release of Met(O) from oxidized proteins as a consequence of accelerated proteolytic degradation. Indeed, oxidation of Met residue in protein has been shown to increase their susceptibility to proteolysis by the multicatalytic protease (6). In addition, the increase in free Met(O) in the msrA mutant may reflect up-regulation of de novo Met synthesis to compensate for the loss of the ability to reduce Met(O) and consequently a decrease in the steady-state level of free Met needed for protein synthesis. The latter possibility is consistent with the observation that the level of total free Met [Met(O) + Met] is 6-fold higher in the msrA mutant than in the wild-type strain when grown in medium containing H2O2 or AAPH (data not shown).

In view of the fact that Met residues are among the first to be attacked by almost all forms of reactive oxygen species (HO⋅, O3, H2O2, ROOH, ROO⋅, RO⋅, HOCl, ONOO−, etc.), and that oxidized Met residues are readily reduced back to Met by MsrA, Levine et al. (6) proposed that Met residues in proteins may serve as a “built-in” antioxidant defense system to protect proteins from oxidation under conditions of oxidative stress. This concept is consistent with the results presented here. Overall, MsrA exerts its protection against oxidative stress by maintaining a low level of oxidized Met, either in protein-bound or free amino acid form; thus, in effect it serves as an antioxidant. Also, by keeping the level of protein Met(O) down, MsrA decreases the need for degradation of Met(O)-rich proteins and their replacement by de novo synthesis. The required levels of free Met needed for protein synthesis is maintained also by salvaging free Met from free Met(O) by the MsrA; therefore, suppressing the need for de novo synthesis of Met.

Further experiments are underway to determine what factors regulate the transcription and expression of the yeast Met(O) reductase under different levels of oxidative stress.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Alan Hinnebusch for the yeast strains, and Drs. Reed Wickner, Rodney L. Levine, and P. Boon Chock for helpful discussions.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AAPH

2,2-azobis-(2-amidino-propane) dihydrochloride

- Met

methionine

- Met(O)

methionine sulfoxide

- MsrA

peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase enzyme

- yeast strain ΔmsrA::URA3

yeast null mutant of peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase gene

- IPTG

isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside

References

- 1.Moskovitz J, Weissbach H, Brot N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;93:2095–2099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moskovitz J, Jenkins N A, Gilbert D J, Copeland N G, Jursky F, Weissbach H, Brot N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;93:3205–3208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brot N, Fliss H, Coleman T, Weissbach H. Methods Enzymol. 1984;107:352–360. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(84)07023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babior B M. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:659–669. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197803232981205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moskovitz J, Rahman A M, Strassman J, Yancey S O, Kushner S R, Brot N, Weissbach H. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:502–507. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.502-507.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine R L, Mosoni L, Berlett B S, Stadtman E R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15036–15040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito H, Fukuda Y, Murata K, Kimura A. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brot N, Werth J, Koster K, Weissbach H. Anal Biochem. 1982;122:291–294. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minetti G, Balduini C, Brovelli A. Ital J Biochem. 1994;43:273–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fliss H, Weissbach H, Brot N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:7160–7164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.23.7160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy V Y, Desrochers P E, Pizzo S V, Gonias S L, Sahakian J A, Levine R L, Weiss S J. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4683–4691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wizemann T M, Moskovitz J, Pearce B J, Cundell D, Arvidson C G, So M, Weissbach H, Brot N, Masure R H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7985–7990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiramoto K, Johkoh H, Sako K, Kikugawa K. Free Radical Res Commun. 1993;19:323–332. doi: 10.3109/10715769309056521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]