Clinicians know that breast feeding is crucial to infant health in developing countries, but they may be less aware of the potential longer term health benefits for mothers and babies in developed countries, particularly in relation to obesity, blood pressure, cholesterol, and cancer. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breast feeding (breast milk only, with no water, other fluids, or solids) for six months, with supplemental breast feeding continuing for two years and beyond. Governments in the United Kingdom have adopted this recommendation, but it presents an enormous challenge for countries like the UK and the United States, where breast feeding rates have been low for decades and can seem remarkably resistant to change. In this review, we will focus mainly on developed countries, with reference to the global context. We will summarise the evidence for the beneficial effects of breastfeeding on health, discuss the epidemiology, and provide practical guidance for managing problems associated with breast feeding. We highlight new developments in infant growth charts and current controversies around HIV and donor breast milk.

Sources and selection criteria

We searched several databases—including Medline and Embase—using the keywords “breastfeeding”, “breast-feeding”, “breast feeding”, and “infant feeding”. We also searched Issue 4 2007 of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines, World Health Organization systematic reviews, Clinical Evidence, and personal reference archives.

How does breast milk differ from formula milk?

Formula milk is just a food, whereas breast milk is a complex living nutritional fluid that contains antibodies, enzymes, and hormones, all of which have health benefits. In addition, some methods of delivering formula milk expose the baby to serious risks of infection. Early intake of colostrum, which is rich in antibodies, is especially important in developing countries, and the small volume of colostrum helps to prevent renal overload when the newborn baby is adjusting its fluid balance.

What are the health benefits of breast feeding?

Tables 1 and 2 summarise the short term and long term health benefits for the infant and mother (taken from two evidence based reviews).1 2 Caution is needed when assessing evidence from observational studies in high income countries, as these are prone to bias and confounding by educational and socioeconomic factors. For low birthweight infants (below 2500 g), evidence from systematic reviews shows that breast milk reduces mortality and morbidity and has a beneficial effect on neurodevelopment and growth.3 4

Table 1.

Short term and long term health benefits of breast feeding for the child in developed countries3 4

| Condition | Incidence or risk reduction | Studies included | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal infection | Reduced risk of diarrhoea in 1st year for infants who were breast fed compared with those who were not (OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.74)1 | 1 systematic review of 14 cohort studies and 3 case control studies | Risk reduction taken from 1 case-control study only; few studies controlled for potential confounders |

| Lower respiratory tract diseases | Reduced risk of hospital admission for respiratory disease in term infants <1 year who were exclusively breast fed for >4 months compared with those who were formula fed (OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.54)1 | Meta-analysis of 7 cohort studies | Good quality meta-analysis with adjustment for potential confounders |

| Acute otitis media | Reduced risk when comparing ever breast fed with never breast fed (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.91) and exclusive breast feeding for >3 months with never breast fed (0.50, 0.36 to 0.70)1 | 5 cohort studies and 1 case- control study | Studies were of moderate or poor quality; potential confounders were not considered in some studies |

| High blood pressure | Reduction of <1.5 mm Hg in systolic and <0.5 mm Hg in diastolic blood pressure in adults who were ever breast fed compared with formula fed1; reduction of 1.21 mm Hg (95% CI to 1.72 to −0.70) in systolic and 0.49 mm Hg (−0.87 to −0.11) in diastolic blood pressure in adults who were ever breast fed compared with formula fed2 | Two meta-analyses evaluated 26 studies, with 13 studies common to both1; meta-analysis of 30 mostly cohort and cross sectional studies2 | Duration and exclusivity of breast feeding varied; age ranged from 1 to 71 years; publication bias and residual confounding are possible |

| Total cholesterol | 0.18 mmol/l and 0.2 mmol/lreduction in total and low density lipoprotein cholesterol in adults who were ever breast fed compared with formula fed1; 0.18 mmol/l (95% CI −0.30 to −0.06) reduction in mean total cholesterol in adults who were ever breast fed compared with formula fed2 | 1 meta-analysis of 37 cohort and case-control studies1; 1 meta-analysis with 28 estimates of total cholesterol from 23 cohort studies and cross sectional studies2 | Analyses of potential confounders, particularly age and fasting status, varied; no significant effect was seen in children or adolescents |

| Overweight and obesity | Reduced risk of obesity in adolescence or as an adult for ever breast fed compared with never breast fed (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.86 and 0.93, 0.88 to 0.99) in two meta-analyses; a third meta-regression found a 4% risk reduction (unadjusted OR 0.96/month of breast feeding, 0.94 to 0.98) of being overweight in adult life for each additional month of any breast feeding in infancy1; people who had ever been breast fed were less likely to be overweight or obese as adults (0.78, 0.72 to 0.84)2 | Two meta-analyses of 9 and 17 cohort studies or cross sectional studies and one systematic review using meta-regression of 28 cohort or cross sectional studies1; meta-analysis of 33 mainly cohort studies or cross sectional studies2 | Weight was examined at different time points; not all potential confounders were adjusted for; larger studies controlling for socioeconomic status and parental anthropometry showed a statistically significant protective effect, making confounding and publication bias less likely |

| Type 1 diabetes | Any breast feeding for >3 months compared with breast feeding <3 months reduced the risk of childhood type 1 diabetes (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.89 and 0.88, 0.81 to 0.96)1 | Two meta-analyses of 18 and 17 case-control studies | Not all confounders were adjusted for and exclusivity of breast feeding varied; 5 of 6 subsequent studies report similar results |

| Type 2 diabetes | Any breast feeding reduced the risk in later life compared with exclusive formula feeding (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.851 and 0.63, 0.45 to 0.89)2 | Meta-analysis of 7 mostly cohort and cross sectional studies1; meta-analysis of 5 cohort studies2 | Not all primary studies adjusted for all important confounders and publication bias is possible |

| Necrotising enterocolitis | Reduced risk when comparing breast milk with formula milk in preterm births (risk ratio 0.42, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.96)1 | Meta-analysis of 4 trials in preterm infants (n=1134) | Gestational age ranged from 23 to 33 weeks and birth weight from <1 kg to >1.6 kg |

| Childhood leukaemias | Any breast feeding for at least 6 months reduced the risk of acute lymphocytic leukaemia (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.91) and acute myelogenous leukaemia (0.85, 0.73 to 0.98)1 | One meta-analysis of 14 case-control studies | The included studies were of good or moderate quality |

| Pain during procedures | Breast feeding or supplemental breast milk alleviated pain during a single painful procedure compared with placebo or positioning or no intervention5 | Systematic review of 11 randomised or quasi-randomised controlled trials of term infants (n=10 300) | Studies varied in the control used and in both physiological and behavioural pain assessment measures |

| Atopic dermatitis | Reduced risk comparing children with a family history of atopy exclusively breast fed >3 months with those breast fed for <3 months (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.92)1 | 1 meta-analysis of 18 prospective cohort studies | Heterogeneity in age of onset and duration of atopic dermatitis |

| Childhood asthma | Reduced risk for infants without a family history of asthma in children <10 who were breast fed (mixed or exclusive) for >3 months compared with those who were not breast fed (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.94)1; conflicting evidence for infants with a family history of asthma | Meta-analysis of 12 prospective cohort studies with a mean follow-up of 4.1 years; 10 prospective cohort studies | Equivocal conclusions from more recently published studies of moderate quality; relation between breast feeding and risk of asthma in older children is unclear |

| Cognitive development in infants | No definitive conclusion in term or preterm infants1; performance in childhood intelligence tests was higher in those breast fed for >1 month (mean difference 4.9, 95% CI 2.97 to 6.92)2 | 3 meta-analyses of 40, 24, and 11 mostly cohort studies, 7 subsequent cohort studies, and 1 secondary analysis in term infants; 8 cohort studies in preterm infants1; meta-analysis of 7 higher quality cohort studies and one randomised controlled trial2 | Not all primary studies adjusted for maternal education or intelligence, which reduces the advantage from breast feeding |

| Sudden infant death syndrome | Any breast feeding was associated with a reduction in risk compared with exclusive formula feeding (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.81)1 | One meta-analysis of 7 case-control studies fitting strict selection criteria | Essential requirements: autopsy confirmed diagnosis, adjustment for sleeping positions, maternal smoking, socioeconomic status |

CI=confidence interval; OR=odds ratio.

Table 2.

Short term and long term health benefits of breast feeding for mothers in developed countries3 4

| Condition | Incidence or risk reduction | Studies included | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | Reduced risk of 4.3% for each year of breast feeding in one meta-analysis and 28% reduction for >12 months’ breast feeding in another1; 1 of the meta-analyses and the systematic review reported decreased risk mainly in premenopausal women | Two meta-analyses and 1 systematic review of 47, 23, and 27 cohort and case control studies | No studies evaluated exclusive breast feeding; 3 primary studies published subsequently report consistent findings |

| Ovarian cancer | Any breast feeding was associated with a reduced risk of ovarian cancer compared with never breast feeding (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.91)1 | Meta-analysis of 9 case-control studies | Moderate and poor quality studies with inconsistent reporting of breast feeding |

| Type 2 diabetes | For women without a history of gestational diabetes, each additional year of breast feeding was associated with a reduced risk (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.73 in one cohort; 0.76, 0.71 to 0.81 in the other)1 | Two large cohorts from the USA nurses health study, one prospective (n=83 585) and one retrospective (n=73 418) | In women with a history of gestational diabetes, breast feeding had no significant effect |

| Postnatal depression | Three studies found an association between early cessation of breast feeding or not breast feeding and an increased risk of postnatal depression1; cause and effect cannot be determined | Six prospective cohort studies (n=5524) | Studies of moderate or poor quality; no studies screened for depression at baseline; unclear definitions of breast feeding |

CI=confidence interval; OR=odds ratio.

In the developing world, low immunisation rates, contaminated drinking water, and reduced immunity as a result of malnutrition make breast feeding crucial to reducing life threatening infections. A review of interventions in 42 developing countries estimated that exclusive breast feeding for six months, with partial breast feeding continuing to 12 months, could prevent 1.3 million (13%) deaths each year in children under 5.6 In comparison, Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine could prevent 4% of all child deaths and measles vaccine 1% of such deaths. Breast feeding also suppresses ovulation, so that women who are still breast feeding are less likely to become pregnant than those who are not breast feeding.

In the UK millennium cohort survey of 15 890 infants, six months of exclusive breast feeding was associated with a 53% decrease in hospital admissions for diarrhoea and a 27% decrease in respiratory tract infections each month; partial breast feeding was associated with 31% and 25% decreases, respectively.7 The results of this study suggested that the protective effects wore off soon after breast feeding ceased, contrary to smaller cohorts, which have reported benefits for up to seven years.8

How have breastfeeding rates changed?

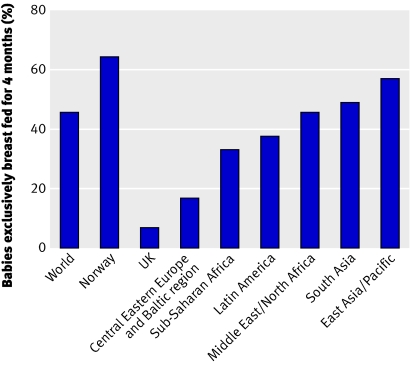

Modified cows’ milk was first manufactured at the end of the 19th century and subsequently breastfeeding rates started to fall, reaching an all time low in developed countries in the 1960s. Worldwide, exclusive breast feeding until 4 months of age (fig 1) seemed to rise from 48% to 52% during the 1990s. The low quality of comparable robust data worldwide is a problem, however. In 2005, the prevalence of exclusive breast feeding until 4 months was 7% in the UK,9 in contrast to 64% in Norway, a comparable developed country. The proportion of babies who are breast fed initially (even for just one feed) has increased steadily since 1990. Older, better educated mothers, who do not smoke, and who have higher socioeconomic status are more likely to breast feed, as are mothers who have previously breast fed or who were breast fed themselves.9

Fig 1 Exclusive breastfeeding at 4 months in 1995-2000 (from Unicef data). Data come from different years and different sources, not all of which are comparable

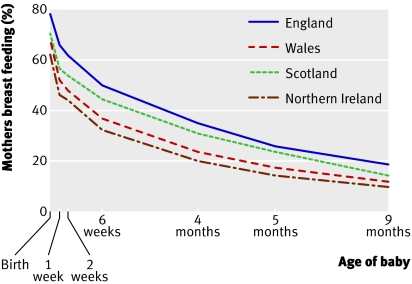

Of concern, the biggest decline in breast feeding occurs during the first four days after birth, when 12% of women in the UK stop, with 22% stopping by two weeks and 37% by six weeks (fig 2).9 Early skilled help is extremely important, as nine out of 10 mothers say they would like to have breast fed for longer.

Fig 2 Prevalence of breast feeding up to the age of 9 months in 20059

Breastfeeding practices vary across different cultures—for example, around 50 cultures withhold colostrum from babies in the first 48 hours.10 Second and subsequent generations of immigrants are beginning to adopt UK customs, with a consequent decline in the number of women who start breast feeding and the duration of breast feeding.11

What interventions might increase breastfeeding rates?

Three Cochrane reviews of randomised controlled trials of interventions to promote and support breast feeding and a National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) review cover this topic.12 13 14 15 Interventions tailored to particular cultural or socioeconomic groups and multifaceted interventions seem to be most effective.12 15 However, the overall quality of trials is poor, health system and cultural contexts are often not comparable, and interventions are heterogeneous.

Summary points

The best option is exclusive breast feeding for six months, with no solids or other fluids, and supplemental breast feeding for two years or more

Breast feeding has important health benefits, including reduced risk of infection in babies and reduced risk of breast and ovarian cancer in mothers

Breast feeding has potential long term health benefits in children—reduced blood pressure, cholesterol concentrations, and obesity

Early assessment of breast feeding and skilled help is the key to preventing problems

New WHO growth charts will establish the breastfed infant as the biological norm with which all children should be compared and will be applicable to all ethnic groups

During pregnancy

Results of five studies from the US (582 women) indicate that education during pregnancy can increase the numbers of women on low income who start breast feeding,12 but overall, evidence for effective interventions is lacking. A Cochrane systematic review looking at the effect of interventions during pregnancy on the duration of breast feeding is in progress.

In hospital

In hospital, early skin to skin contact between mothers and babies (30 trials, 1925 participants),16 frequent and unrestricted breast feeding to ensure continued production of milk (three old trials, new trials considered unethical),15 and help with positioning and attaching the baby (one trial, 160 women)15 increase the chances of breast feeding being successful (table 3). The NICE guidelines on postnatal care recommend the Unicef “baby friendly hospital initiative” is implemented as a minimum standard. This initiative is supported by evidence from several studies, including trials, and has an important health professional training component.10 15 Two trials (1431 women) have found that giving birth in a home-like environment increases the number of women who start breast feeding and continue breast feeding for six to eight weeks.17 Women spend less time in hospital after birth these days, and NICE has concluded that this does not affect the duration of breast feeding.10 18 Caution is needed, however, as breast feeding was a secondary outcome measure. Nine trials (3730 women) have provided convincing evidence that giving mothers commercial discharge packs containing formula or promotional material for formula milk reduces the number of women who exclusively breast feed until 10 weeks.19

Table 3.

Prevention and management of breast feeding problems

| Problem and evidence | Characteristics | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Breast discomfort or pain; Cochrane systematic review (8 trials, 424 women),20 and NICE guidelines10 | A normal full breast is tender; breast engorgement can occur on days 2-7 when milk “comes in;” breasts can become shiny, oedematous, and painful; if milk is not removed, milk production will diminish | Assessment of effective breast feeding;* frequent unrestricted breast feeding; analgesia compatible with breast feeding; breast massage; hand expression if necessary; cabbage leaves or cold compresses may help, but observed effects could be a placebo effect |

| Sore nipples; formal consensus or expert opinion10; a Cochrane review is in progress | Often caused by suction trauma secondary to incorrect positioning; nipples may range in appearance from mildly red to cracked and scabbed; mothers or babies (or both) may have evidence of Candida albicans infection (thrush), particularly if receiving perinatal antibiotics | Correct positioning and attachment may prevent pain; if nipple pain persists after repositioning and reattachment, thrush infection should be considered; prescribing for thrush is contentious; topical antifungal agents should be prescribed as first line; fluconazole is not licensed for use in breastfeeding mothers, but it is licensed for use in neonates at higher doses than are likely to be transferred in breast milk; topical nipple treatments, nipple shells, or nipple shields have not been shown to be effective; evidence for the safety of nipple cream is weak; principles of moist wound healing apply21 |

| Mastitis; mainly observational studies and small poor quality trials10 | Cellulitis of connective tissue caused by a blocked milk duct and poor milk drainage; with time, bacteria (usually Staphylococcus aureus, occasionally β haemolyicstreptococci) grow; signs and symptoms range from local inflammation with minimal systemic symptoms to abscess formation and rarely septicaemia | Continue breast feeding or expressing milk to maximise effective drainage; assessment of effective breast feeding;* analgesia compatible with breast feeding; increase fluid intake; gently massage to help remove any duct blockage; if symptoms continue for more than a few hours of self management, seek professional advice to decide whether a β lactamase resistant antibiotic is indicated |

| Inverted nipples; formal consensus and expert opinion10 | Flat or inverted nipples may require skilled help with positioning and attachment | No contraindications to breast feeding; good practice is to offer women additional care and support |

| Breast implants; a case series of adverse event reports22 | Concern that exposure to biomaterials in breast implants may leach into breast milk | Safety largely unknown |

| Breast reduction surgery; small retrospective observational studies23 | Partial breast feeding is usually possible, but milk supply may be reduced because of interruption of nerves or blood vessels | Assessment of effective breast feeding* |

| Difficulty getting the baby to suck; observational studies10 | Often cited by women as a problem9; narcotic analgesia may adversely affect early sucking behaviour after birth | Assessment of effective breast feeding;* good practice is to encourage extended skin to skin contact16 and offer help to express milk |

| Early weight loss >10% of baby’s weight; expert opinion and case studies10 | Transient early weight loss is normal in healthy babies; however, hypernatraemic dehydration can occur in an otherwise healthy full term, breastfed baby because of poor milk intake, and in extreme cases can lead to brain injury and death | A traditional consensus rule is that babies who lose >10% of their weight should be assessed in a hospital where biochemical tests are available, although this rule has recently been questioned24; assessment should include urine output, stool frequency and character, observation for lethargy or fractious behaviour, and assessment of effective breast feeding* |

| Poor weight gain; observational studies and expert opinion10 (see separate discussion on growth charts) | Almost all mothers can produce enough milk; perceived “insufficient milk” is a complex phenomenon and is a common reason for giving up breast feeding8 | Assessment of effective breast feeding;* reassure and help mothers to gain confidence in their ability to produce enough milk; insufficient evidence is available to determine the optimal frequency of weighing babies; frequent weighing may be undesirable, as short term fluctuations may increase anxiety |

| Neonatal jaundice10; consensus or expert opinion | About 50% of term and 80% of preterm babies develop physiological jaundice within the first week; it is more common in breastfed babies; “breast milk jaundice” is a prolonged unconjugated jaundice, which lasts beyond 14 days, and the mechanism is unknown | Breast feed frequently and wake the baby to feed if necessary; do not routinely supplement with formula, water, or other fluids; investigate jaundice persisting beyond 14 days, even in well babies, to exclude other causes like biliary atresia |

| Ankyloglossia (tongue tie); systematic review based on 1 trial and observational studies25 | A congenital short frenulum, which is often asymptomatic, can resolve spontaneously, and may interfere with feeding; expert opinions differ about definition and diagnosis | Assessment of effective breast feeding;* early division is safe and effective when tongue tie is causing breastfeeding problems |

*Assessment of effective breast feeding should be carried out by a skilled person who has received training. It involves observing and assessing feeding pattern, positioning and attachment, sucking behaviour, and breast fullness.

After birth

A Cochrane review of 34 trials (29 385 women) found that additional professional or lay support increases the duration of any breast feeding to six months, with a greater effect for exclusive breast feeding.13 Exclusive breast feeding was prolonged by WHO and Unicef professional training for health professionals (meta-analysis of six trials). Unicef UK has extended the baby friendly initiative to community healthcare settings; the effectiveness of this policy is still to be evaluated.

Policy interventions

Breastfeeding targets have recently been set in England and Northern Ireland, but their effect is yet to be evaluated. In Scotland, although rates increased, no health board achieved a 1994 target of 50% of babies being breast fed at six weeks by 2005. In 2006, when targets were no longer in place, breastfeeding rates declined in Scotland for the first time in 10 years. No trials have investigated support for breast feeding in the workplace. In Britain, only one in seven working mothers had the facilities to express milk or to breast feed at work.26 In 2005, the Breastfeeding (Scotland) Act made it an offence to prevent or stop a mother breast feeding a child under 2 years in public. In the same year a UK survey of 7186 mothers found that Scottish residents had the most positive experiences of breast feeding in public.9

What clinical problems arise when breast feeding?

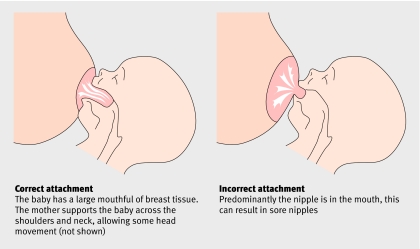

Correct positioning and attachment of the baby at the breast (fig 3) are crucial to establishing and sustaining effective breast feeding. When a mother and baby are learning to breast feed, good practice is for a trained person to observe feeds and provide skilled help and support. Getting the first few feeds right can prevent problems like breast or nipple pain, poor milk supply, and early infant weight loss. Table 3 gives details of associated clinical problems.

Fig 3 Positioning and attachment of the baby on the breast. Adapted, with permission, from the Unicef UK baby friendly initiative

How should doctors prescribe for breastfeeding mothers?

Doctors tend to be overcautious when prescribing for breastfeeding mothers, and specific advice or subtle cues can undermine breast feeding.27 Careful use of expert resources (box), however, can usually enable breast feeding to continue. Each prescribing decision needs to take account of the risks and benefits to the individual mother and baby, including the indication for treatment, the pharmacokinetic properties of the drug, the age of the baby, the volume of feeds, and the frequency of feeds. Unfortunately, standard adult reference texts like the British National Formulary may be unhelpful. Drug manufacturers are not required to license drugs for use by breastfeeding mothers, and they tend to be cautious and recommend against use. Most published data on safety rely on case studies or small samples of fewer than 20 mothers. However, if a drug is licensed for infants, then the small amounts present in breast milk are likely to be safe, so the British National Formulary for Children is a better guide to maternal prescribing.

Guidance for prescribing in breastfeeding mothers

General

Most common conditions can be prescribed for safely using the information in this box—mothers need stop breast feeding only rarely

Prescribe drugs in the British National Formulary for Children that are licensed for use under age 2 years

Use drugs with a relative infant dose <10% of the maternal dose

Avoid newly developed drugs with little information available

Choose drugs that bind to plasma proteins because only small amounts of these drugs are transferred into milk

Drugs that should be used with caution and monitored

Some antiepileptics

Some antipsychotics

Central nervous system sedatives

Combined oral contraceptives (not advised for mothers with babies <3 months old)

Lithium

Diuretics

Drugs that should be avoided

Chemotherapy

Reference sources

British national formulary for children—www.medicinescomplete.com/mc/

Drugs in Lactation Advisory Service—www.ukmicentral.nhs.uk/drugpreg/guide.htm

Hale TW. Medication and mother’s milk. 12th ed. Texas: Pharmasoft Medical Publishing, 2006

Drugs and lactation database—http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi

Breastfeeding Network Drugline (a registered charity)—www.breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk

Current hot topics

New growth charts based on breastfed babies

Until 2006, growth charts were based on children with mixed feeding patterns, predominantly bottle fed, but evidence from various studies suggested that exclusively breastfed infants gained weight differently. Concerns were that misinterpretation of growth charts could lead to breastfed babies being given unnecessary supplements of formula. This led WHO to develop new charts using data collected from six centres worldwide over 15 years. These are intended to be standards of optimum growth, rather than average growth. All data were from children born to non-smoking mothers in non-deprived circumstances who had been breast fed for a year, exclusively for four months, with complementary solids started by 6 months of age. The resulting data show an extraordinary similarity of linear growth between populations and confirm that breastfed infants show a lower weight trajectory from 6 months onwards.28

The Department of Health has recently recommended that the WHO charts be adopted for all children from 2 weeks to 2 years, with a planned launch by early 2009. This allows the UK to keep its valuable birth weight for gestation charts. The new charts will establish breastfed infants as the biological norm—with whom all children should be compared—and they will be applicable to all ethnic groups. After these charts are adopted fewer infants will be defined as underweight or weight faltering, whereas the proportion who are overweight will increase.29 A supporting educational programme will therefore be essential.

Tips for non-specialists

When opportunities arise, inform pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers of the health benefits of breast feeding their infant for six months

Encourage mothers and boost their confidence in their ability to breast feed

Prevention and early help with breastfeeding problems are crucial. Ensure that pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers know where they can get skilled professional or lay help 24 hours a day, seven days a week

If you do not have the skills to assess whether breast feeding is effective, refer the woman to someone who does have the skills and also has the time to observe breast feeds

HIV and breast feeding

WHO consensus guidelines for HIV positive women vary according to context, place, and the individual. Exclusive breast feeding for six months is recommended where no culturally acceptable, feasible, affordable, safe, and sustainable nutritional substitutes for breast milk are available. Otherwise, breast feeding should be avoided in an attempt to prevent new perinatal HIV infections. A Cochrane review of this subject is in progress.

Donor breast milk banks

Throughout history donor milk has been the choice of some parents, and it is currently recommended as second choice if the mother’s own milk is not available.3 However, the risk of possible transmission of HIV, cytomegalovirus, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease has recently caused concern about regulation of the 17 UK donor milk banks. Evidence on donor milk is limited and of poor quality.30 The extent to which pasteurised donor breast milk retains the biological properties of mother’s milk is uncertain. Further evidence about the health benefits and economics is needed to develop evidence based guidance.

Nutrition

A varied and balanced diet is recommended to sustain breast feeding, which requires about 2.09 MJ of extra energy a day. NICE guidance to improve the nutrition of pregnant and breastfeeding mothers is now available.31

Low vitamin D concentrations in residents of the northern hemisphere are a concern and recommendations about supplements vary between countries. Little vitamin D is secreted into breast milk, and NICE recommends supplements for all pregnant and breastfeeding mothers.31 A Cochrane review is in progress.

Additional educational resources for patients

Telephone helplines

The following organisations are a good source of information and they offer telephone helplines staffed by highly trained breastfeeding specialists; some offer chat rooms and support groups:

Department of Health (www.breastfeeding.nhs.uk/); 0844 20 909 20

National Childbirth Trust (www.nct.org.uk/); 0870 444 8708

Breastfeeding Network (www.breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk/); 0844 412 4664

La Leche League (www.laleche.org.uk/); 0845 120 2918

Association of Breastfeeding Mothers (http://abm.me.uk/website/index.htm); 08444 122 949

Good sources of information and video clips

Dipex (www.dipex.org/breastfeeding)—Video clips of women talking about their breastfeeding experiences and web links to other information resources

Best Beginnings (www.bestbeginnings.info/)—Video clips of breastfeeding positioning and attachment

Other good sources of information

Department of Health. Birth to five: 2007 edition. (www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/)—An easy to use and practical booklet for parents on all aspects of child health and nutrition

Health Promotion Agency for Northern Ireland (www.breastfedbabies.org/)—Provides help and support to make breast feeding easier

Health Scotland. Breastfeeding and returning to work: Off to a good start. (http://www.healthscotland.com/documents/1571.aspx)—A booklet about all aspects of combining breast feeding with work

Food Standards Agency. Breastfeeding your baby (www.eatwell.gov.uk/agesandstages/baby/breastfeed/)—Advice on what to eat when breast feeding

Additional educational resources for health professionals

The World Health Organization (www.who.int/)—Information on the global strategy and data bank for infant feeding, the baby friendly hospital initiative, child growth standards, health benefits, HIV, and the microbiological risks of formula feeding procedures

Unicef UK baby friendly initiative (www.babyfriendly.org.uk/)—Supports health services to provide high quality care. Information about training and the latest research updates

Unicef (www.childinfo.org/eddb/brfeed/index.htm)—Breastfeeding and complementary feeding statistics by country

Department of Health (www.dh.gov.uk/en/Policyandguidance/)—Information on breastfeeding policy, rates, and initiatives in England

Health Promotion Agency for Northern Ireland (www.healthpromotionagency.org.uk/ )— Information on breastfeeding policy, rates, and initiatives in Northern Ireland

National Services Scotland (www.isdscotland.org/isd/4811.html)—Scottish health statistics on breast feeding

National Assembly for Wales (www.wales.nhs.uk/publications/bfeedingstrategy-e.pdf)—Information about promoting breast feeding in Wales

Where do we need to go now?

All health professionals should actively support breast feeding as an important way to improve child health. Better implementation of existing evidence—particularly the baby friendly initiative—is needed, as are improvements in the education of healthcare professionals. Adherence to WHO’s International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes is also important in both developing and developed countries. New approaches are required at policy and individual level to deal with health inequalities, consider incentives to breast feed, facilitate breast feeding outside the home, and to find the most effective ways of teaching and learning breastfeeding skills. Meanwhile, the early days after birth are crucial and everyone in health care should chip away at the complex psychological, social, cultural, and health service organisation factors that undermine breast feeding.

Contributors: PH drafted the review. All authors helped collect data and write the paper. All authors are guarantors. Thanks to Jane Britten, Magda Sachs, Wendy Jones, and Linda Wolfson for their helpful comments on drafts of this review.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ip S, Cheung M, Raman G, Chew P, Magula N, DeVine D, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evidence report/technology assessment. Report 153. Rockville, USA: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2007.

- 2.Horta BL, Bahl R, Martines JC, Victora CG. Evidence of the long-term effects of breastfeeding Geneva: WHO, 2007. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241595230_eng.pdf

- 3.Edmond K, Bahl R. Optimal feeding of low-birth-weight infants: technical review Geneva: WHO, 2006. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2006/9789241595094_eng.pdf

- 4.Henderson G, Anthony M, McGuire W. Formula milk versus maternal breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(4):CD002972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah PS, Aliwalas L, Shah V. Breastfeeding or breast milk to alleviate procedural pain in neonates: a systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(3):CD004950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS; Bellagio Child Survival Study Group. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet 2003;362:65-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quigley MA, Kelly YJ, Sacker A. Breastfeeding and hospitalization for diarrheal and respiratory infection in the United Kingdom millennium cohort study. Pediatrics 2007;119:e837-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson AC, Forsyth JS, Greene AS, Irvine L, Hau C, Howie PW. Relation of infant diet to childhood health: seven year follow up cohort of children in Dundee infant feeding study. BMJ 1998;316:21-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolling K, Grant K, Hamlyn B, Thornton A. Infant feeding survey 2005. United Kingdom: Information Centre, Government Statistical Service, 2007

- 10.Demott K, Bick D, Norman R, Ritchie G, Turnbull N, Adams C, et al. Routine postnatal care of women and their babies London: National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care and Royal College of General Practitioners, 2006 [PubMed]

- 11.Hawkins SS, Lamb K, Cole TJ, Law C; the Millennium Cohort Study Child Health Group. Effect on maternal health behaviours of moving to England: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2008. (in press); doi: 10.1136/bmj.39532.688877.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyson L, McCormick F, Renfrew MJ. Interventions for promoting the initiation of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(2):CD001688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Britton C, McCormick FM, Renfrew MJ, Wade A, King SE. Support for breastfeeding mothers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(1):CD001141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gagnon AJ. Individual or group antenatal education for childbirth/parenthood, or both. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(3):CD002869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renfrew MJ, Wallace LM, D’Souza L, McCormick F, Spiby H, Dyson L. The effectiveness of public health interventions to promote the duration of breastfeeding: systematic reviews of the evidence. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2005

- 16.Moore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(3):CD003519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodnett ED, Downe S, Edwards N, Walsh D. Home-like versus conventional institutional settings for birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(1):CD000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown S, Small R, Faber B, Krastev A, Davis P. Early postnatal discharge from hospital for healthy mothers and term infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(3):CD002958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donnelly A, Snowden HM, Renfrew MJ, Woolridge MW. Commercial hospital discharge packs for breastfeeding women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD002075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snowden HM, Renfrew MJ, Woolridge MW. Treatments for breast engorgement during lactation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(2):CD000046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones V, Grey JE, Harding KG. Wound dressings. BMJ 2006;332:777-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown SL, Todd JF, Cope JU, Sachs HC. Breast implant surveillance reports to the US Food and Drug Administration: maternal-child health problems. J Long Term Eff Med 2006;16:281-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aillet S, Watier E, Chevrier S, Pailheret J, Grall J. Breast feeding after reduction mammaplasty performed during adolescence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2002;101:79-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Dommelen P, van Wouwe J, Breuning-Boers J, van Buuren S, Verkerk P. Reference chart for relative weight change to detect hypernatraemic dehydration. Arch Dis Child 2007;92:490-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Division of ankyloglossia (tongue-tie) for breastfeeding 2005. www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=284318

- 26.Abdulwadud OA, Snow ME. Interventions in the workplace to support breastfeeding for women in employment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(3):CD006177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson PO, Pochop SL, Manoguerra AS. Adverse drug reactions in breastfed infants: less than imagined. Clin Pediatr 2003;42:325-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Onis M, Garza C, Onyango AW, Borghi E. Comparison of the WHO child growth standards and the CDC 2000 growth charts. J Nutr 2007;137:144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright C, Lakshman R, Emmett P, Ong K. Implications of adopting the WHO 2006 child growth standard in the UK: two prospective cohort studies. Arch Dis Child 2007; online 1 Oct 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Quigley M, Henderson G, Anthony M, McGuire W. Formula milk versus donor breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(4):CD002971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guidance for midwives, health visitors, pharmacists and other primary care services to improve the nutrition of pregnant and breastfeeding mothers and children in low income households. 2008. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/index.jsp?action=byID&o=11943