Abstract

Interleukin-16 (IL-16) acts as a chemoattractant for CD4+ cells, as a modulator of T-cell activation, and plays a key role in asthma. This report describes the cytokine-inducing effects of IL-16 on total peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and PBMC subpopulations. While CD4+ T lymphocytes did not secrete cytokines in response to rhIL-16, CD14+ CD4+ monocytes and maturing macrophages secrete IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) upon rhIL-16 stimulation. The mRNA species for these four cytokines were detected as early as 4 hr post-stimulation, with protein being secreted by 24 hr. Secretion of IL-1β and IL-6 by total PBMC was dose dependent, with maximal secretion being observed using 50 ng/ml rhIL-16. However, for IL-15 or TNF-α maximal secretion by total PBMC occurred with all concentrations between 5 ng/ml to 500 ng/ml rhIL-16. Purified monocytes/macrophages secreted maximal concentrations of all four cytokines in the presence of 500 ng/ml rhIL-16, except for monocytes where maximal secretion of IL-15 was, interestingly, observed with only 50 ng/ml rhIL-16. The use of higher concentrations of rhIL-16 (1000 ng/ml) inhibited secretion of all four cytokines. While these IL-16-induced cytokines are likely to be involved in the immune system's response to antigen, the data suggest that IL-16 may play a key role in initiating and/or sustaining an inflammatory response.

Introduction

Cytokines are important multifunctional mediators of cell behaviour and cell-to-cell communication, whose functions vary from being stimulatory, inhibitory to migratory. The manner in which they affect the cells in the environment is frequently also dependent on the presence or absence of other cytokines.

Interleukin-16 (IL-16) is still a relatively uncharacterized cytokine. IL-16 is initially produced as a precursor, pro-IL-16, a 67000 MW protein of 631 amino acids.1 The C-terminal portion of pro-IL-16 is cleaved at Asp253 by caspase-3 releasing the bioactive 121-amino acid IL-16.2 CD8+ T lymphocytes constitutively store pro-IL-16 mRNA and protein, as well as bioactive IL-16, which is secreted upon stimulation with histamine, serotonin and concanavalin A.3 Mast cells similarly constitutively store pro-IL-16 mRNA and protein, and secrete active IL-16 upon C5a and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) stimulation.4 Eosinophils also contain pro-IL-16 mRNA and protein, although these cells apparently secrete IL-16 without additional stimulus.5 Bronchial epithelial cells from asthmatic patients have also been shown to secrete bioactive IL-16.6 The known functions of IL-16 include induction of the IL-2Rα on T cells,7 suppression of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) replication8–10 and inhibition of T-cell antigen receptor/CD3 mediated T-cell stimulation in mixed lymphocyte reactions.11 In addition, IL-16 acts in concert with IL-2 and/or IL-15 to promote CD4+ T-cell proliferation,12 and is a chemoattractant factor for CD4+ cells.13 IL-16 has also been shown to play a key role in airway hyper-responsiveness and up-regulation of immunoglobulin E (IgE).14

Because, to date, no data has been published on the cytokine cascade initiated by IL-16, we decided to investigate which cytokines are secreted by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), CD4+ T lymphocytes and CD14+ monocytes/macrophages in response to IL-16 stimulation. This information would also help understand what role IL-16 may play, via other cytokines, in the general immune response. Because direct proof of an interaction between IL-16 and CD4 has yet to be shown, we also wanted to determine if CD4+ T lymphocytes and CD4+ monocytes/macrophages are equally responsive to IL-16.

Materials and methods

In vitro cell culture

Fresh human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBMC) from healthy donors (n = 20) were isolated by Ficoll/Hypaque gradient centrifugation. Total PBMC or purified cell populations were cultured at 1 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 4 mm l-glutamine, 100 µg/ml penicillin/streptomycin (cRPMI) supplemented with or without rhIL-16 or with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (5 µg/ml). For cultures requiring macrophages, monocytes were isolated using CD14 microbeads (see below), and cultured in cRPMI at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml in the presence of 100 U/ml granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Calbiochem, Schwalbach, Germany). For time course experiments, cells were cultured (± rhIL-16) for 2, 4, 8, 24 or 48 hr. Cells from the 2, 4, and 8 hr samples were used for RNA extractions and detection of cytokine mRNA by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR). Supernatants from the 8, 24 and 48 hr cultures were used for direct detection of cytokines by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The IL-16 used in these experiments was an endotoxin-free recombinant form of human IL-16 (rhIL-16) synthesized by Roche Diagnostics (Penzberg, Germany) (endotoxin levels: < 0·1 endotoxin unit/10 µg protein). To test for specificity, a neutralizing anti-IL-16 antibody (Pharmingen, Hamburg, Germany) was added to the cell cultures at a concentration of 0·2 µg/ml per 15 ng/ml IL-16.

Magnetic cell sorting

CD14+ monocytes and CD4+ T lymphocytes were isolated by magnetic cell sorting (MACS) CD14 or CD4 microbeads, respectively, according to manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). CD14+ monocytes were isolated first, and the CD14– fraction used to isolate the CD4+ T-cell population (being devoid of CD14+ CD4+ cells). The remaining cells were used as the CD14– CD4– fraction. The purified cell populations were > 95% pure, as determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis.

RNA extractions and RT–PCR

Total RNA was extracted from total PBMC using the Qiagen RNeasy kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). cDNA synthesis (RT) was performed using the First-strand cDNA synthesis kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pharmacia, Braunschweig, Germany). PCR amplifications were performed on 2 µl cDNA sample in a 40-µl final volume using a PTC-100 Thermal cycler (Biozym, Hess. Oldendorf, Germany) also containing 1 U Taq polymerase (Perkin Elmer, Weiterstadt, Germany), 2 µl 5 mm dinucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) and 4 µl PCR buffer (Perkin Elmer). Thirty-five PCR cycles were carried out as follows: 94° for 30 s, 55° for 30 s and 72° for 1 min. Primers for IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), GM-CSF, regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) and reduced glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were purchased from R & D systems (Weisbaden, Germany). Sequences for the remaining primers were as follows: IL-3F: CGA CAA AGT CGT CTG TTG AG; IL-3R: GCC TTT GCT GGA CTT CAA C; IL-8F: CTC ACT GTG TGT AAA CAT GAC; IL-8R: TTC TTG GAT ACC ACA GAG AAT G; IL-9F: GAT CCT GGA CAT CAA CTT CC; IL-9R: GCC TCT CAT CCC TCT CAT C; IL-11F: CTG TGT TTG CCG CCT GGT C; IL-11R: CCC GTC AGC TGG GAA TTT G; IL-13F: CTC ATG GCG CTT TTG TTG AC; IL-13R: GAT GCT TTC GAA GTT TCA GTT G; IL-15F: GAG AAG TAT TTC CAT CCA GTG; IL-15R: GCA ATC AAG AAG TGT TGA TGA AC; proIL-16F: CAA GCT CGA GAG CCC AGG CAA GC; proIL-16R: TGT TAT TGG CTT TGG CTT C; MIP-1αF: GGT GTC ATC ACC AGC ATC; MIP-1αR: GGA AGG GGA GCC ATT TAA C (MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein). Samples were visualized in ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels under ultraviolet (UV) light. Similar amounts of GAPDH cDNA were obtained from each sample., Cytokine sandwich ELISA, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15, and TNF-α protein levels were detected using a sandwich ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions (R & D systems). Serial dilutions of rhIL-1β, rhIL-6, rhIL-15 and rhTNF-α, respectively, were used for the standard curves. The absorbance of the standards and samples were measured at 405 nm. The minimum detectable concentrations were 4 pg/ml for IL-1β, 3 pg/ml for IL-6, 4 pg/ml for IL-15 and 15 pg/ml for TNF-α. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis to identify differences between samples. Significance was established at the P < 0·05 level of confidence.

Results

Production of cytokine mRNA by total PBMC stimulated with IL-16

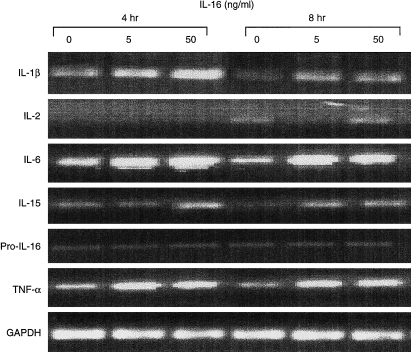

Total human PBMC were cultured in the presence of 5 ng/ml or 50 ng/ml of rhIL-16. Cells were cultured for 2, 4 or 8 hr, RNA extracted and RT–PCR for the various cytokines performed. Two hours following incubation with either rhIL-16 concentration, no increase in mRNA, compared to PBMC cultured in the absence of rhIL-16, was detected for any of the cytokines tested. However, after 4 hr, increases in the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and TNF-α were detected, primarily in the samples incubated with 50 ng/ml rhIL-16 (Fig. 1). Less pronounced increases in these cytokines were also detected in samples incubated with 5 ng/ml rhIL-16 (Fig. 1). No changes (increases or decreases) were seen in the levels of IL-2 and pro-IL-16 (Fig. 1), as well as for IL-1α, IL-3, IL-4, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-11, IL-13, IFN-γ, GM-CSF, MIP-1α, or RANTES mRNA (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Cytokine specific RT–PCR for IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-15, proIL-16, TNF-α and GAPDH after rhIL-16 stimulation (0, 5 or 50 ng/ml rhIL-16) for 4 or 8 hr.

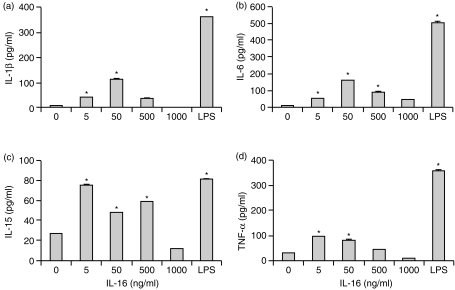

Production of cytokine proteins by total PBMC stimulated with IL-16

Because increases in IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and TNF-α mRNA levels were detected after stimulation of PBMC with rhIL-16, it was necessary to see if and when the proteins of these cytokines were being released. Supernatants from PBMC incubated with 5 ng/ml, 50 ng/ml, 500 ng/ml or 1000 ng/ml for 8, 24 and 48 hr, were isolated and tested for expression of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and TNF-α by ELISA. After 8 hr, no significant increases in the concentrations of either of these cytokines were detected in supernatants (data not shown). However, after 24 hr, there were significant increases in the concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and TNF-α. Secretion of IL-1β and IL-6 was induced with 5, 50 and 500 ng/ml of rhIL-16, with maximal secretion being seen with 50 ng/ml (Fig. 2a, b). IL-15 was also secreted in response to 5, 50 and 500 ng/ml of rhIL-16 where all three concentrations induced secretion (Fig. 2c). TNF-α was also detected in supernatants of PBMC stimulated with 5, 50 and 500 ng/ml rhIL-16 (Fig. 2d). It should be noted that the decreased level of TNF-α secreted in the presence of 500 ng/ml IL-16 was not always observed, with the amount of TNF-α sometimes being similar to that seen with 5 or 50 ng/ml rhIL-16. The use of 1000 ng/ml rhIL-16 seemed to inhibit secretion of all four cytokines. LPS stimulated the production of higher concentrations of the four cytokines than did any of the IL-16 concentrations (Fig. 2). When a neutralizing anti-IL-16 antibody was added to the cultures, production of the four cytokines was inhibited (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Concentrations of (a) IL-1β (b) IL-6 (c) IL-15 and (d) TNF-α secreted by total PBMC stimulated with varying concentrations of rhIL-16 or LPS (5 µg/ml) for 24 hr. The data represent the mean± SD and are representative of 20 donors. An asterisk (*) denotes statistically significant increases in cytokine concentration (P < 0·05).

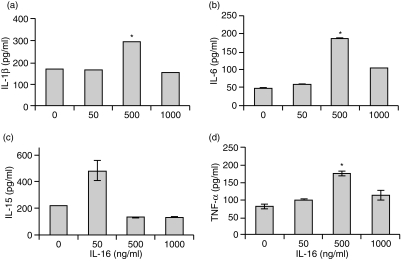

CD4+ T lymphocytes do not secrete cytokines in response to IL-16 stimulation, whereas CD14+ CD4+ monocytes do

To further identify which cells, of the total PBMC population, were being stimulated to secrete the various cytokines by IL-16, CD4+ T lymphocytes or CD14+ monocytes were isolated using CD4 or CD14 MACS beads, respectively, and cultured with either no, 50 ng/ml or 500 ng/ml rhIL-16 for 24 or 48 hr. Supernatants were collected and tested for the presence of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and TNF-α protein by ELISA following rhIL-16 stimulation. As can be seen in Fig. 3, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and TNF-α were detected in the supernatant of CD14+ monocytes 24 hr after stimulation with rhIL-16. At 48 hr, no additional increase in cytokine secretion was seen (data not shown). Maximal secretion of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α was observed with 500 ng/ml rhIL-16 (Fig. 3a, b, d). Interestingly, maximal secretion of IL-15 by monocytes was consistently observed with only 50 ng/ml rhIL-16 (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

Concentrations of (a) IL-1β (b) IL-6 (c) IL-15 and (d) TNF-α secreted by CD14+ monocytes stimulated with varying concentrations of rhIL-16 for 24 hr. The data represent the mean± SD and are representative of 20 donors. An asterisk (*) denotes statistically significant increases in cytokine concentration (P < 0·05).

CD4+ T lymphocytes cultured with rhIL-16 for 24 or 48 hr did not secrete any of these cytokines (data not shown). The population of cells remaining after CD14 and CD4 cell isolation (CD14– CD4– cells) were also cultured with rhIL-16, to determine if these too were being stimulated by rhIL-16 to secrete other cytokines. Like the CD4+ T cells, these cells did not secrete any of these cytokines (data not shown).

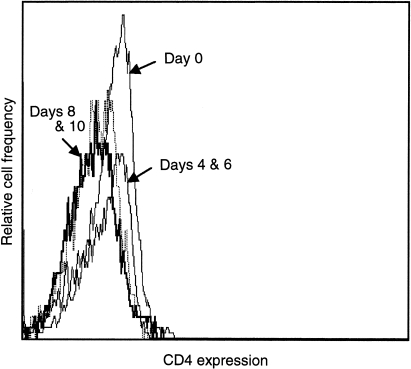

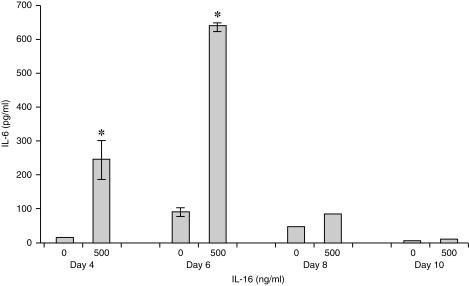

Monocytes lose their responsiveness to IL-16 as they differentiate into mature macrophages

To extend the monocyte responsiveness further, CD14+ monocytes were isolated from peripheral blood and cultured for up to 14 days with GM-CSF to promote differentiation into macrophages.15 Cell samples were removed at days 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14 and analysed for CD4 expression by flow cytometry, or used for culture in the presence of 500 ng/ml rhIL-16 for 24 hr. Supernatants from these IL-16 cultures were tested for IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and TNF-α protein by ELISA. On days 4 and 6, all cells expressed similar levels of CD4 as seen on freshly isolated monocytes (Fig. 4). Following stimulation of day 4 and 6 monocytes/maturing macrophages with IL-16, secretion of the four cytokines was detected (data not shown; see below for detailed study). The most prominent level of secretion was seen on day 6 as shown on a representative graph (Fig. 5; IL-6 secretion). By days 8 and 10, the cells no longer expressed CD4 (Fig. 4) nor did they secrete the four cytokines (Fig. 5, IL-6 data shown). This was similarly seen on days 12 and 14 (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Expression of CD4 on monocytes/maturing macrophages on days 0, 4, 6, 8 and 10 after culture with GM-CSF. The dashed line represents the negative control.

Figure 5.

Concentration of IL-6 secreted by CD14+ monocytes stimulated with 0 or 500 ng/ml rhIL-16 for 24 hr, 4, 6, 8 and 10 days post incubation with GM-CSF. The data represent the mean ± SD and are representative of 20 donors. An asterisk (*) denotes statistically significant increases in cytokine concentration (P < 0·05).

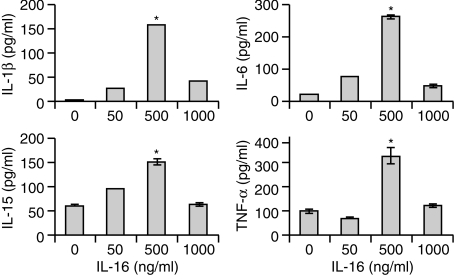

The kinetics of secretion of these maturing macrophages to various concentrations of rhIL-16 was also examined. Monocytes were cultured for 6 days in the presence of GM-CSF, then cultured in the presence or absence of rhIL-16 (0, 50 or 500 ng/ml) for 24 or 48 hr. IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and TNF-α were detected in supernatants of all cultures stimulated with rhIL-16 after 24 hr (Fig. 6). Similar concentrations were observed after 48 hr (data not shown). Maximal secretion for all four cytokines was observed with 500 ng/ml rhIL-16, with significantly lower levels being secreted with only 50 ng/ml rhIL-16 (Fig. 6), and similar to that observed with total PBMC, the use of 1000 ng/ml rhIL-16 inhibited maximal secretion of the four cytokines (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Concentrations of (a) IL-1β (b) IL-6 (c) IL-15 and (d) TNF-α secreted by CD14+ macrophages stimulated with varying concentrations of rhIL-16 for 24 hr. The data represent the mean± SD and are representative of 20 donors. An asterisk (*) denotes statistically significant increases in cytokine concentration (P < 0·05).

Discussion

Over recent years, IL-16 has become a cytokine of interest due to its possible involvement in numerous diseases, in particular aquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and allergy.9,16–18 While it is known which cells secrete IL-16, and the conditions under which secretion is induced, the functions of IL-16 are still not completely known. IL-16 has been shown to induce the expression of CD25 (IL-2R) on T cells,7 induce chemotaxis of CD4+ cells,19 as well as activating the SAPK (stress-activated protein kinase) signalling pathway in macrophages.20 The data presented here demonstrates that CD4+ CD14+ monocytes/maturing macrophages are the population that are responsive to IL-16, in terms of cytokine production, being the only cells in PBMC secreting the cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and TNF-α.

Of all the cytokines tested for, only increases in the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and TNF-α mRNA were detected in cultured human PBMC as early as 4 hr after stimulation with 5 ng/ml or 50 ng/ml rhIL-16. No other cytokine species were detected, nor were there increased levels of pro-IL-16 mRNA. The lack of additional pro-IL-16 mRNA is, however, not completely surprising considering both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes constitutively store pro-IL-16 mRNA, releasing the protein upon the appropriate stimuli,3 although the lack of additional pro-IL-16 mRNA may also suggest that IL-16 does not act in an autocrine manner. IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and TNF-α protein was detected 24 hr post stimulation with either 5, 50 or 500 ng/ml of rhIL-16, although in lower concentrations than that for PBMC stimulated with LPS. Secretion of IL-1β and IL-6 was optimal with 50 ng/ml rhIL-16, and the IL-16 appeared to act in a dose-dependent manner. By comparison, IL-15 and TNF-α were secreted in similar quantities with between 5 and 500 ng/ml rhIL-16. Secretion of these four cytokines was, however, considerably reduced or inhibited when a higher concentration of rhIL-16 (1000 ng/ml) was used. Future studies to investigate this inhibitory effect are planned.

As it has been suggested that CD4 is the ligand for IL-16,7,19 CD14+ monocytes and maturing macrophages, which express low levels of CD4, and CD4+ T lymphocytes were isolated, and cultured under conditions similar to that performed for the total PBMC. Monocytes and maturing macrophages stimulated with rhIL-16 for 24 hr did indeed secrete IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and TNF-α, while the CD4+ T cells were not responsive. Secretion of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α was dose dependent and maximal upon stimulation with 500 ng/ml rhIL-16. Maturing macrophages required a greater amount of rhIL-16 to produce IL-15 than did the monocytes. The maturing macrophages also consistently secreted higher concentrations of IL-6 and TNF-α, in particular, than the monocytes, a factor that has previously been shown for in vitro cultured macrophages and monocytes.21

An interesting point for these culturing systems is the fact that when total PBMC are cultured with rhIL-16, maximal secretion of the four secreted cytokines is observed with only 50 ng/ml rhIL-16, whereas with the purified monocytes/macrophages, maximal secretion is observed with 500 ng/ml rhIL-16. While there may be no clear cut reason for why this effect was observed, it is possible that another factor (cytokine/chemokine?), being secreted in the total PBMC cultures, cell-to-cell contact, or another interaction not provided in the purified cell cultures, induces optimal secretion of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and TNF-α in the presence of less rhIL-16.

While IL-16 has been shown to perform a number of functions, its ability to promote the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α) or cytokines leading to pro-inflammatory activity (IL-15) does suggest a pathophysiological role for IL-16 as a mediator of inflammation.22–24 Another function of IL-16 which could theoretically be regulated by cytokines is the inhibition of HIV replication.8 As the mechanism for this inhibition is not fully understood, it is possible that IL-16 might indirectly be suppressing HIV replication via the production of other cytokines. This, however, does not appear to be the case. First, because no MIP-1α or RANTES were produced, these cytokines being known suppressors of HIV replication,25 it is unlikely that this is a mechanism by which IL-16 inhibits HIV replication, although this is contrary to results shown by Hermann et al. where MIP-1α was produced by macrophages stimulated with 10 µg/ml IL-16.26 Second, and providing more direct evidence, supernatants taken from IL-16 stimulated PBMC and monocyte cultures did not contain a HIV/simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) inhibitory activity (Mathy and Norley, unpublished data). This, therefore, supports the idea that the antiviral effects of IL-16 are not mediated by secondarily induced and secreted factors, but are a direct consequence of IL-16 binding to its target cell.

As a final point, the CD4+ T lymphocytes were not responsive to IL-16 in the manner observed for the monocytes/macrophages. This does not, however, rule out that the receptor for IL-16 is CD4, because, as seen with the monocytes/macrophages, CD4 appears to be necessary for IL-16 responsiveness as the loss of CD4 coincides with the loss of IL-16 responsiveness. Others studies have also shown that the use of the anti-CD4 antibody OKT4 inhibits IL-16 induced chemotaxis.19 However, the fact that CD4+ T lymphocytes were not responsive to IL-16 (as determined by the secretion of the tested cytokines), suggests two possibilities: that the CD4+ T cells are secreting a factor that was not tested for in these experiments, or that a cofactor, present on the CD4+ monocytes/maturing macrophages and not the CD4+ T cells, is necessary for the cytokine-inducing function of IL-16.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Oliver Hohn for assistance with preparation of this manuscript, and Karin Vollhardt for technical assistance. This work was in part supported by contract no. 1506/TG04 from the Federal Ministry of Health. NM is recipient of an EC Marie Curie Research Fellowship.

References

- 1.Baier M, Bannert N, Werner A, Lang K, Kurth R. Molecular cloning, sequence, expression, and processing of the interleukin 16 precursor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Center DM, Wu MH, et al. Processing and activation of pro-interleukin-16 by caspase-3. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laberge S, Cruikshank WW, Kornfeld H, Center DM. Histamine-induced secretion of lymphocyte chemoattractant factor from CD8+ T cells is independent of transcription and translation. J Immunol. 1995;155:2902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rumsaeng V, Cruikshank WW, Foster B, et al. Human mast cells produce the CD4+ T lymphocyte chemoattractant factor, IL-16. J Immunol. 1997;159:2904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim KG, Wan H-C, Bozza PT, et al. Human eosinophils elaborate the lymphocyte chemoattractants IL-16 (lymphocyte chemoattractant factor) and RANTES. J Immunol. 1996;156:2566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellini A, Yoshimura H, Vittori E, Marini M, Mattoli S. Bronchial epithelial cells of patients with asthma release chemoattractant factors for T lymphocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;92:412. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruikshank WW, Berman JS, Theodore AC, Bernardo J, Center DM. Lymphokine activation of T4+ T lymphocytes and monocytes. J Immunol. 1987;138:3817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baier M, Werner A, Bannert N, Metzner K, Kurth R. HIV suppression by interleukin-16. Nature. 1995;378:563. doi: 10.1038/378563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou P, Goldstein S, Devadas K, Tewari D, Notkins AL. Human CD4+ cells transfected with IL-16 cDNA are resistant to HIV-1 infection: inhibition of mRNA expression. Nature Med. 1997;3:659. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Idziorek T, Khalife J, Billaut-mulot O, et al. Recombinant human IL-16 inhibits HIV-1 replication and protects against activation-induced cell death (AICD) Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;112:84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Theodore AC, Center DM, Nicoll J, Fine G, Kornfeld H, Cruikshank WW. CD4 ligand IL-16 inhibits the mixed lymphocyte reaction. J Immunol. 1996;157:1958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parada NA, Center DM, Kornfeld H, et al. Synergistic activation of CD4+ T cells by IL-16 and IL-2. J Immunol. 1998;160:2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Center DM, Cruikshank W. Modulation of lymphocyte migration by human lymphokines. I. Identification and characterization of chemoattractant activity for lymphocytes from mitogen-stimulated mononuclear cells. J Immunol. 1982;128:2563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hessel EM, Cruikshank WW, Van Ark I, et al. Involvment of IL-16 in the induction of airway hyper-responsiveness and up-regulation of IgE in a murine model of allergic asthma. J Immunol. 1998;160:2998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metcalf D, Begley CG, Johnson GR, et al. Biologic properties in vitro of a recombinant human granulocyte– macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 1986;67:37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mashikian MV, Tarpy RE, Saukkonen JJ, et al. Identification of IL-16 as the lymphocyte chemotactic activity in the bronchoalveolar lavage of fluid of histamine-challenged asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101:786. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70403-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laberge S, Durham SR, Ghaffar O, et al. Expression of IL-16 in allergen-induced late-phase nasal responses and relation to topical glucocorticosteroid treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:569. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baier M, Kurth R. Fighting HIV-1 with IL-16. Nature Med. 1997;3:605. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruikshank WW, Center DM, Nisar N, et al. Molecular and functional analysis of a lymphocyte chemoattractant factor: association of biologic function with CD4 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krautwald S. IL-16 activates the SAPK signaling pathway in CD4+ macrophages. J Immunol. 1998;160:5874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gessani S, Testa U, Varano B, et al. Enhanced production of LPS-induced cytokines during differentiation of human monocytes to macrophages: role of LPS receptors. J Immunol. 1993;151:3758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-harthi L, Roebeck KA, Kessler H, Landay A. Inhibition of cytokine-driven human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by protease inhibitor. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1175. doi: 10.1086/514110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LeNaour R, Lussiez C, Raoul H, Mabondzo A, Dormont D. Expression of cell adhesion molecules at the surface of in vitro human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected human monocytes: relationships with tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1beta, and interleukin 6 syntheses. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:841. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musso T, Calosso L, Zucca M, et al. Interleukin-15 activates proinflammatory and antimicrobial functions in polymorphonuclear cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2640. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2640-2647.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cocchi F, De Vico AL, Garzino-demo A, Arya SK, Gallo RC, Lusso P. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1 alpha and MIP-1 beta as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science. 1995;270:1811. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hermann E, Darcissac E, Idziorek T, Carpon A, Bahr GM. Recombinant interleukin-16 selectively modulates surface receptor expression and cytokine release in macrophages and dendritic cells. Immunology. 1999;97:241. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00786.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]