Abstract

Interleukin-16 (IL-16), produced by activated CD8+ T lymphocytes, is inhibitory to human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) replication. In an attempt to determine whether human B cells express and secrete IL-16, a wide panel of B-cell lines derived from patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-associated B-cell lymphomas (AABCL) (n = 5) and from non-AABCLs (n = 8) were studied. Using reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) analysis, we were able to observe ubiquitous expression of IL-16 mRNA. Kinetic studies on constitutive mRNA turnover and secretion for IL-16 suggests that the optimum expression is at 24 hr. Interestingly, we report, for the first time, IL-16 secretion by human B-cell lines.

Introduction

The interleukin (IL)-16 gene, located on chromosome 15, and formerly known as lymphocyte chemoattractant factor, is produced by activated CD8+ T lymphocytes.1,2 IL-16 functions as a chemoattractant for CD4+ T cells,3,4 eosinophils,5 monocytes,3 bronchial epithelial cells6 and macrophages.2 IL-16 has been shown to up-regulate IL-2 receptor (IL-2R or CD25)3,7 and induce the transient loss of responsiveness via the T-cell receptor (TCR). This multifunctional cytokine and its precursor (pro-IL-16) have been detected in various tissues and in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC).8 IL-16 is synthesized in the form of pro-IL-16 with an apparent molecular weight of 80 000.9 Studies suggest that pro-IL-16 is proteolytically cleaved intracellularly to form peptides of 14–17 kDa prior to secretion.8 However, for biological function, these peptides multimerize to form 56-kDa homotetramers. Western blot analysis with antibodies to the 14-kDa protein enabled identification of an 80-kDa protein, suggesting the presence of pro-IL-16.8,9 Although IL-16 appears to autoaggregate to form bioactive multimers,8 the mechanism of IL-16 secretion remains uncertain. IL-16 does not appear to have any homology with any previously described cytokines.10 The role of IL-16 in diseases is characterized by CD4+ T-cell involvement, as observed in multiple sclerosis,11,12 asthma4,13 and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).14–16 Besides its function as a chemoattractant, IL-16 is also known as a modulator of T-cell activation and as a potential inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) replication.14,15,17 Given the pivotal role of this cytokine in AIDS, defining cellular distributions of IL-16 will enhance our understanding of IL-16 production and secretion. In this report we demonstrate that tumour-derived human B-cell lines express IL-16 mRNA ubiquitously and secrete IL-16 protein, irrespective of whether or not these cells have integrated Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) genome.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

The study included 13 tumour B-cell lines derived from patients with undifferentiated lymphomas of Burkitt’s and non-Burkitt’s origin, as described previously.18 The characteristics of these cells are summarized in Table 1. Five of these cell lines – 10C9, 2F7, HBL-1, HBL-2 and HBL-3 – are AIDS-associated B-cell lines (AABCL). 10C9 is an EBV+ human B-cell line established from a non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patient with AIDS. 2F7 is also EBV+, and was established from a Burkitt’s lymphoma patient with AIDS. HBL-1, HBL-2 and HBL-3 were derived from patients with AIDS-associated lymphomas and were a kind gift from Dr Riccardo Dalla-Favera (Columbia University, NY). HBL-1 is EBV+, whereas HBL-2 and HBL-3 are EBV–.19 HIV-1 viral sequences were not detected in any of these cell lines. The non-AABCLs comprised five EBV– American Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines: BJAB, EW36, CA46, ST486 and MC116; and three EBV+ African Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines: Raji, Namalva and Daudi. Establishment of the B-cell lines, together with their phenotypic characteristics, have been reported previously.18,20,21 All cell lines were maintained in suspension culture in RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Cellgro; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) at 37° in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

Table 1.

Characteristics of B-cell lines

| Cell line | EBV status | Continent | Histology | Tissue source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines | |||||

| AABCL | 10C-9 | Positive | N. America | Burkitt’s | Peripheral blood |

| 2F7 | Positive | N. America | Burkitt’s | Peripheral blood | |

| HBL-1 | Positive | N. America | UL | Peripheral blood | |

| HBL-2 | Negative | N. America | UL | Pleural effusion | |

| BL-3 | Negative | N. America | UL | Liver | |

| Non-AABCL | BJAB | Negative | N. America | Burkitt-like | Lymphoblastoid |

| EW36 | Negative | N. America | UL | Pleural effusion | |

| CA46 | Negative | S. America | Burkitt-like | Ascitic fluid | |

| ST486 | Negative | N. America | UL | Ascitic fluid | |

| MC116 | Negative | N. America | UL | Pleural effusion | |

| African Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines | |||||

| Non-AABCL | Raji | Positive | Africa | Burkitt’s | Jaw tumour |

| Daudi | Positive | Africa | Burkitt’s | Orbital tumour | |

| Namalva | Positive | Africa | Burkitt’s | Lymphoblastoid | |

AABCL, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-associated B-cell line; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; UL, undifferentiated lymphoma.

Exposure of cells to phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

Cells obtained on day 4 of subculture were resuspended in fresh medium at a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/ml. The cells were incubated in 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks at 37° for various lengths of time in the presence or absence of the tumour promoter phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO). A wide range of PMA concentrations (5–100 ng/ml) was studied, and optimal results were obtained at a concentration of 10 ng/ml. Control and PMA-activated cultures were harvested at designated time-points, and the cells were immediately processed for RNA isolation. The supernatants were collected and stored at − 80° until assayed for IL-16 secretion. Total cellular RNA was extracted from control and PMA-activated cells using guanidinium isothiocyanate–phenol chloroform, as described previously.18,20,21

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) analysis for detection of interleukin-16 transcript

Using a Perkin-Elmer PE2400 Thermal Cycler (Perkin-Elmer Foster City, CA), cDNAs were prepared by reverse transcription (RT) of 1 µg of total RNA, as previously described.18,20–23 Briefly, 5 µl of the cDNA sample was amplified with 2·5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Fisher). The reaction mixture consisted of 20 pmol of each of the sense and antisense primers in PCR buffer, 2 m m MgCl2 and 200 µ m each of dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP. The mixture was amplified over 30 cycles. The first two cycles consisted of denaturation at 97° for 1 min, primer annealing at 60° for 1 min, and primer extension at 72° for 1 min. An additional 28 cycles of denaturation at 94° for 1 min were followed with similar annealing and primer extension conditions as used in the first two cycles. A final extension was performed at 72° for 7 min, followed by storage at 4°. Primers were designed based on the sequence published by Baier et al.14 Specific primers for the upper and lower strands consisted of bp 789–808: 5′-GACCTCAACTCCTCCACTGA-3′; and bp 1111–1130: 5′-CTCCTGATGACAATCGTGAC-3′, respectively. Primers were custom made by Bioserve (Laurel, MD) and were used to amplify a 341-bp region of the IL-16 transcript. The housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was amplified concurrently with IL-16 using the same RT mixture. The primers used for GAPDH amplification have been published previously.18,20–23 The amplicons were detected by ethidium bromide staining after electrophoresis through 2% Tris-borate/EDTA agarose gels. Semiquantification of relative intensities of the PCR amplicons was performed using the Collage 3·0 intensity scanning function (Macintosh, Apple Computer Inc., Cupertino, CA). Intensity readings were quantified by comparing the IL-16 expression levels with those of GAPDH.

Cloning and sequencing of RT–PCR products

The 341-bp amplicons of IL-16 and 358-bp sequence of GAPDH from two representative cell lines, HBL-1 and Raji, were subcloned into the dephosphorylated HincII site of the pBluescript II plasmid vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), following modification with T4 DNA polymerase to remove the 3′ non-template-directed base addition, as previously described.18,20–23 Briefly, the blunt-end amplicons were treated with T4 polynucleotide kinase and ligated into the vector using T4 DNA ligase at 12° overnight. After transformation of competent bacteria, white colonies growing in Luria–Bertani medium (LB) agar containing 100 µg/ml of ampicillin, 40 µg/ml of isopropylthio-β- d-galactoside and 40 µg/ml of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-inodyl-β- d-galactoside, were selected and grown in 5 ml of Terrific Broth with 100 µg/ml of ampicillin. Plasmid mini preparations were performed by alkaline lysis of 1·5 ml of the overnight culture. Plasmids containing the appropriate size inserts, as determined by electrophoresis through 1·5% Tris-acetate/EDTA agarose after restriction digestion, were sequenced using the Applied Biosystems Sequencer model 373A (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

IL-16 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Supernatants obtained from control and PMA-activated cells were collected and 100 µl of the supernatant was assayed. After normalizing for equal amounts of protein, secreted IL-16 was detected using the Cytoscreen immunoassay kit (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA), following the manufacturer’s guidelines. This kit recognizes both precursor and mature forms of IL-16. The minimum detectable dose, without apparent cross-reactivity to various cytokines and adhesion molecules, was < 5 pg/ml, as outlined by the manufacturer.

Results

Detection of the IL-16 transcript by using RT–PCR

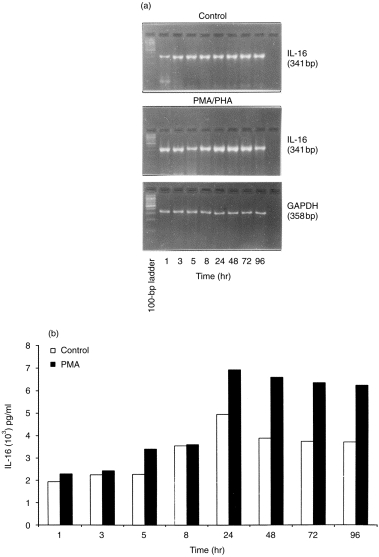

The HBL-1 cell line was used as a representative B-cell line to study the kinetics of IL-16 mRNA transcripts and secretion from 1 to 96 hr in culture. HBL-1 cells obtained on day 3 after subculture were resuspended at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/ml in fresh medium containing 10% FCS and incubated at 37° with and without PMA for 1, 3, 5, 8, 24, 48, 72 and 96 hr. At each time-point, the culture was harvested for RNA isolation, and the supernatants were collected for ELISA. As shown in Fig. 1(a), constitutive IL-16 transcripts were expressed from 1 hr with a peak accumulation at 24 hr. Furthermore, mitogen stimulation augmented mRNA expression by ≈ onefold, as compared to untreated control cells, at each time-point. To ensure that the differences seen in mRNA expression at these time-points were not caused by variations in PCR efficiency or relative amounts of amplicon products, but indeed reflected changes in IL-16 kinetics, these expressions were normalized to that of GAPDH and repeated several times. Figure 1(b) displays a time-course secretion of IL-16 in HBL-1. Although the constitutive secretion of IL-16 was detected as early as 1 hr, increased secretion in control and PMA-stimulated cells was observed from the 24 hr time-point onwards.

Figure 1.

Time-course kinetics of mRNA expression and secretion of interleukin-16 (IL-16). At the indicated time-points, HBL-1 control and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-stimulated cultures were harvested, total RNAs were extracted from cell pellets and IL-16 expression was analysed by using the reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) (a). Supernatants were assayed for IL-16 secretion by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (b). PHA, phytohaemagglutinin.

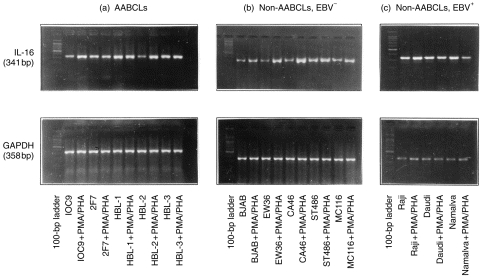

Having identified the optimal time-point for IL-16 expression and secretion as 24 hr in the representative HBL-1 cell line, we performed RT–PCR analysis several times on constitutive and PMA-induced expression of IL-16 in all the other B-cell lines. All the 13 cell lines (Table 1) expressed IL-16 mRNA transcript constitutively, as shown in Fig. 2. However, upon mitogen stimulation in the AABCLs (Fig. 2a), a twofold increase in IL-16 expression was observed in 10C9, no change in 2F7, HBL-1 or HBL-3 and a fourfold increase in HBL-2. Figure 2(b) shows constitutive and PMA-induced expression of IL-16 for all non-AABCLs that were EBV.– Upon PMA stimulation, we observed a 0·8-fold increase in IL-16 expression in the EW36 cell line, and no significant changes for BJAB, CA46, ST486 and MC116 cell lines. Figure 2(c) shows constitutive and PMA-induced expression of IL-16 in EBV+ African Burkitt’s lymphoma B-cell lines. We did not observe any significant change upon mitogen stimulation in Raji, Daudi or Namalva cells. In essence, ubiquitous constitutive expression of IL-16 mRNA was observed in every tumour-derived B-cell line studied in this work. The presence or absence of EBV did not appear to be a factor affecting IL-16 expression because both EBV+ and EBV– cell lines expressed IL-16 mRNA.

Figure 2.

Interleukin-16 (IL-16) expression as determined by using reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) analysis. (a) Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-associated B-cell lines (AABCLs); (b) non-AABCLs, Epstein–Barr virus negative (EBV–); and (c) non-AABCLs, EBV+. The 341-bp amplicon of IL-16 was generated from total RNAs isolated from control and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-stimulated cells. The 358-bp amplicon represents glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) for semiquantification by densitometry. PHA, phytohaemagglutinin.

Cloning and sequencing IL-16 and GAPDH RT-PCR products

We cloned and sequenced the 341-bp amplicons of IL-16, and the 358-bp of GAPDH, from two representative cell lines, HBL-1 and Raji. The IL-16 sequence was identical to the sequence reported previously by Baier et al.14 The GAPDH sequence was identical to sequence previously described18,20–23 (data not shown).

Il-16 ELISA

Secretion of IL-16 was quantified using standard IL-16 protein provided by the manufacturer (BioSource). Least-square-fit linear regression analysis was performed on the absorbance value measured by using an EL309 microplate autoreader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT), and the results are summarized in Table 2. We did not observe any specific patterns of IL-16 secretion between AABCLs, EBV– non-AABCLs and EBV+ non-AABCLs at the 24 hr time-point. The data, as shown in Table 2, suggests heterogeneity in IL-16 secretion.

Table 2.

Analysis of interleukin-16 (IL-16) secretion by human B-cell lines

| IL-16 secretion (pg/ml) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell line | EBV status | Control | PMA | |

| American Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines | ||||

| AABCL | 10C-9 | Positive | 2686 | 3176 |

| 2F7 | Positive | 672 | 811 | |

| HBL-1 | Positive | 4933 | 4991 | |

| HBL-2 | Negative | 1040 | 2907 | |

| BL-3 | Negative | 1054 | 1152 | |

| Non-AABCL | BJAB | Negative | 75 | 75 |

| EW36 | Negative | 131 | 233 | |

| CA46 | Negative | 886 | 1254 | |

| ST486 | Negative | 2862 | 3119 | |

| MC116 | Negative | 2252 | 2397 | |

| African Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines | ||||

| Non-AABCL | Raji | Positive | 583 | 835 |

| Daudi | Positive | 1366 | 2257 | |

| Namalva | Positive | 1846 | 2257 | |

AABCL, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-associated B-cell line; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate.

Discussion

Studies of the role that B cells play in pathogenesis have identified several important cytokines, such as IL-10, IL-7, IL-12 and macrophage inflammatory protein-1a (MIP-1a), some of which are secreted in an autocrine manner.18,20,21,24 These findings suggest that modulation of viral expression may be influenced by some of these regulatory cytokines. In addition, some of the soluble factors secreted by B cells may, in fact, have suppressive effects on viral replication. Although B cells are not natural targets for HIV, their transformation with EBV may cause expression of the CD4 molecule, thus facilitating viral infection.25 The binding of IL-16 to CD4 results in activation of p56lck, the function of which is essential for the chemotactic response.26

Zhou et al. demonstrated that transfection of CD4+ Jurkat cells with IL-16 dramatically reduced the expression of HIV-1 tat and rev transcripts, as analysed by RT–PCR analysis.17 To determine whether IL-16 mRNA is modulated by HIV-1 tat, RT–PCR analysis was performed on HIV-1 tat-transfected B-cell (Raji-tat) and T-cell (Jurkat-tat) lines. The Jurkat-tat cell line was obtained from The AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH (Bethesda, MD; donated by Drs A. Caputo, W. Haseltine and J. Sodroski) and the Raji-tat cell line was a gift from Dr J. Sodroski (Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA). The Raji-tat and Jurkat-tat cell lines were used in a previous study on cytokine modulation of HIV-1 tat transfection.23 In a later work, no dramatic changes were observed with regard to IL-16 mRNA expression or secretion, either constitutively or with PMA induction, as compared to non-transfected Jurkat or Raji control cells (data not shown).

Several exciting features can be deduced from the results of the present work. IL-16 expression and secretion has been demonstrated for the first time in tumour-derived human B-cell lines. It is tempting to speculate that the histology and tissue source of these cell lines may be attributed to the heterogeneous expression and secretion of IL-16. EBV– B-cell lines are generally not known for their cytokine production,18,20,21 with the exception of MC116 for MIP-1α.18 However, we observed expression and secretion of IL-16 mRNA in all EBV– cell lines. To conclude, the recognition that B cells are a source of IL-16 adds to the cytokines known to be formed by this class of lymphocytes.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by funds from the Department of Biology and the small grant award from the research and graduate studies (nos: 5302-240-22 and 5302-255-22), University of West Florida, Pensacola, FL-32514 (V. S.). We thank John VanSteenbergen and Edward P. Ravey for assistance, John Blackie for photographs and Dr S. Bagui for statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Center DM, Berman JS, Kornfeld H, Theodore AC, Cruikshank WW. The lymphocyte chemoattractant factor. J Lab Clin Med. 1995;125:167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center DM, Kornfeld H, Cruikshank WW. Interleukin 16 and its function as a CD4 ligand. Immunol Today. 1996;17:476. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10052-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruikshank WW, Center DM, Nisar N, et al. Molecular and functional analysis of a lymphocyte chemoattractant factor: association of biologic function with CD4 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruikshank WW, Long A, Tarpy R, et al. Early identification of interleukin-16 (lymphocyte chemo-attractant factor) and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of antigen-challenged asthmatics. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:738. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.6.7576712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim KG, Wan H, Bozza PT, et al. Human eosinophils elaborate the lymphocyte chemoattractants. J Immunol. 1996;156:2566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellini A, Yoshimura H, Vittori E, Marrini M, Mattoli S. Bronchial epithelial cells of patients with asthma release chemoattractant factors for T-lymphocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;92:412. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruikshank WW, Center DM, Berman JS, Bernardo J, Theodore AC. Lymphokine activation of T4+ T lymphocytes and monocytes. J Immunol. 1987;138:3817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chupp GL, Wright EA, Wu D, et al. Tissue and T cell distribution of precursor and mature IL-16. J Immunol. 1998;161:3114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baier M, Bannert N, Werner A, Lang K, Kurth R. Molecular cloning, sequence, expression, and processing of the interleukin 16 precursor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schall T. The chemokines. In: Thomson A, editor. The Cytokine Handbook. New York: Academic Press; 1994. p. 419. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biddison WE, Taub DD, Cruikshank WW, Center DM, Connor EW, Honma K. Chemokine and matrix metalloproteinase secretion by myelin proteolipid protein-specific CD8+ T cells: potential roles in inflammation. J Immunol. 1997;158:3046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schluesener HJ, Scid K, Kretzeschmer J, Myermann R. Leukocyte chemotactic factor: a natural ligand to CD4 is expressed by lymphocytes and microglial cells of the MS plaque. J Neurosci Research. 1996;44:606. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960615)44:6<606::AID-JNR11>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laberge S, Ernst P, Ghafar O, et al. Increased expression of interlukin 16 in bronchial mucosa of subjects with atopic asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:193. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.2.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baier M, Bannert N, Werner A, Metzner K, Kurth R. HIV suppression by interleukin 16. Nature. 1995;378:563. doi: 10.1038/378563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maciaszek JW, Prada NA, Cruikshank WW, Center DM, Kornfeld H, Vigilanti GA. IL-16 represses HIV-1 promoter activity. J Immunol. 1997;158:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scala E, D’Officzi G, Rosso R, et al. C-C chemokines, IL-16, and soluble antiviral factor activity are increased in cloned T cells from subjects with long-term nonprogressive HIV infection. J Immunol. 1997;158:4485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou P, Goldstein S, Devadas K, Tewari D, Notkins A. Human CD4+ cells transfected with IL-16 cDNA are resistant to HIV-1 infection: inhibition of mRNA expression. Nature Med. 1997;3:659. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma V, Walper D, Deckert R. Modulation of macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha and its receptors in human B-cell lines derived from patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and Burkitt’s lymphoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;235:576. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaidano G, Parsa N, Tassi V, et al. In vitro establishment of AIDS-related lymphoma lines: phenotypic characterization, oncogene and tumour suppressor gene lesions, and heterogeneity in Epstein–Barr viral infection. Leukemia. 1993;7:1621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benjamin D, Sharma V, Knobloch T, Armitage R, Dayton M, Goodwin R. Human B cell lines constitutively secrete IL-7 and express IL-7 receptors. J Immunol. 1994;152:4749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benjamin D, Sharma V, Kubin M, et al. IL-12 expression in AIDS-related lymphoma B cell lines. J Immunol. 1996;156:1626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma V, Xu M, Vail J, Campbell R. Comparative analysis of multiple techniques for semi-quantitation of RT–PCR amplicons. Biotechnol Techniques. 1998;12:521. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma V, Knobloch TJ, Benjamin D. Differential expression of cytokine genes in HIV-1 tat transfected T and B cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;208:704. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benjamin D, Park C, Sharma V. Human B cell interleukin 10. Leukemia Lymphoma. 1994;12:205. doi: 10.3109/10428199409059591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montagnier L, Gruest J, Chamaret S, et al. Adaptation of lymph-adenopathy associated virus (LAV) to replication in EBV transformed B lymphoblastoid cell lines. Science. 1984;225:63. doi: 10.1126/science.6328661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan TC, Kornfeld H, Collins LT, Center DM, Cruikshank WW. The CD4-associated tyrosine kinase p56lck is required for lymphocyte chemoattractant factor-induced T-lymphocyte migration. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]