Abstract

In the last decade, more than half of U.S. children were born to working mothers and 65% of working men and women were of reproductive age. In 2004 more than 28 million women age 18–44 were employed full time. This implies the need for clinicians to possess an awareness about the impact of work on the health of their patients and their future offspring. Most chemicals in the workplace have not been evaluated for reproductive toxicity, and where exposure limits do exist, they were generally not designed to mitigate reproductive risk. Therefore, many toxicants with unambiguous reproductive and developmental effects are still in regular commercial or therapeutic use and thus present exposure potential to workers. Examples of these include heavy metals, (lead, cadmium), organic solvents (glycol ethers, percholoroethylene), pesticides and herbicides (ethylene dibromide) and sterilants, anesthetic gases and anti-cancer drugs used in healthcare. Surprisingly, many of these reproductive toxicants are well represented in traditional employment sectors of women, such as healthcare and cosmetology. Environmental exposures also figure prominently in evaluating a woman’s health risk and that to a pregnancy. Food and water quality and pesticide and solvent usage are increasingly topics raised by women and men contemplating pregnancy. The microenvironment of a woman, such as her choices of hobbies and leisure time activities also come into play. Caregivers must be aware of their patients’ potential environmental and workplace exposures and weigh any risk of exposure in the context of the time-dependent window of reproductive susceptibility. This will allow informed decision-making about the need for changes in behavior, diet, hobbies or the need for added protections on the job or alternative duty assignment. Examples of such environmental and occupational history elements will be presented together with counseling strategies for the clinician.

Keywords: Reproductive, Reproductive toxicants, Environmental exposure

Introduction

The influence of environmental exposures on the general status of health has been increasingly acknowledged for numerous disease outcomes. The connection between air pollution and acute respiratory disease, for example and, more recently, the observation linking poor indoor air quality to increases in the incidence of childhood asthma has been widely publicized. Such epidemiologic observations are often reported in the media and, when combined with the growing public interest in a clean and healthy environment, have translated into an increasingly sophisticated patient population that expects healthcare providers to be conversant with the environmental contribution to disease risk. Indeed, the lay public often has shown more interest in– and occasionally knowledge of– the relationship between health and the environment than has the medical community.

Medical educators and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) both have addressed this dilemma by promoting enhanced medical student and physician training in environmental medicine in order to develop ‘environmentally literate’ physicians. In this brief, the term ‘environmental medicine’ will refer to “diagnosing and caring for people exposed to chemical and physical hazards in their homes, communities and workplaces through such media as contaminated soil, water and air” [1, 2]. This definition was taken from a 1992

IOM Committee report on Curriculum Development in Environmental Medicine. The preconception clinical visit already includes environmental history queries regarding smoking and alcohol use, [3] but must be enlarged to address the broader concept of environmental exposures occurring in the woman’s home, community and workplace.

Sources of environmental exposure

Organizing the environmental exposure history can be facilitated by using the definition referred to above and by eliciting information on aspects of the patient’s larger environment; this includes the specific community locale (workplace and her home environment) and infrastructure which relates to air quality and soil or water pollution, all of which the patient deals with on a regular basis.

Community

Surprisingly, a clinician would likely not know if a given patient in his/her practice was living in an area near by an environmentally polluted location, such as a National Priority Listed (NPL) waste site or a local toxic waste dump. In large metropolitan areas, many such sites are present and unknown to most citizens. Although clinically significant exposure to a toxic hazard present on the site would be unlikely to threaten the wider community, a risk may exist for some residents living very close to the site, possibly allowing for soil or drinking water contamination. In specific instances often covered by the news media, patients would likely be able to report knowledge of living in the vicinity of such a place. Such a ‘self-report’ response could be elicited by simply asking the question, “Do you live near or have contact with a waste site?” Probably the most potentially important exposure opportunity is via contaminated drinking water. Here the biggest risk is usually from a small private water source such as a well, not subject to municipal water treatment standards and testing. According to the EPA approximately 15% of the U.S. population has a private drinking water source.

Workplace

An intimate relationship exists between occupational and environmental health, because often the source of environmental contamination is a former (or present day) work site. The workplace is an important ‘special case’ in environmental history taking, because populations exposed at work tend to be exposed at higher concentrations than the larger community, regardless whether contamination is via air, water or soil. Thus, though the working population is smaller than the public at large, workers are exposed at higher ‘doses’. It is thus sometimes observed that workers are the ‘canaries’ or ‘sentinels’, exhibiting first the health effects which might be expected in a wider community exposure from an environmental pathway.

It is fair to say that the principal exposure opportunity to an environmental reproductive or developmental toxicant in patients will be from their work place. Many toxicants with unambiguous reproductive and developmental effects are still in regular commercial or therapeutic use, and thus pose a continued potential risk in the occupational environment. Several employment sectors where such toxicants commonly are found employ women workers primarily and include: laboratory and clinical medicine, printing and dry cleaning [4] though this is clearly not always the case and the gender mix varies by sector. (See Table 1). Whereas some of these chemical toxicants are regulated by public health agencies, the majority of chemicals considered for regulation are not evaluated for reproductive endpoints [5] but rather, for other toxic effects. This gap in the regulatory safety net allows reproductive toxicants to be encountered in both environmental and work settings by men and women.

Table 1.

Employment sectors and associated reproductive/develop-mental toxicants

| Sector | Toxicant | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Pesticides/Herbicides | Ethylene Dibromide |

| Manufacturing | Organic Solvents | Glycol ethers, lead, |

| Heavy Metals | Cadmium | |

| Dry Cleaning | Solvents | Perchloroethylene |

| Printing | Solvents/inks | |

| Pharmaceutical Compounding/Manufacture | Hazardous Drugs | Antineoplastics, hormones, immunologic modifiers |

| Health Care | Biologics | Rubella, CMV, Hepatitis virus |

| Physical Agents | Ionizing Radiation/Heat | |

| Chemicals | Antineoplastics/Hazardous Drugs Anesthetic Gases Sterilants | |

| Physical Exertion | Lifting/Prolonged Standing Shift Work |

Note. Ref: Summarized from GAO, 1988; Stellman, 1994.

Home

Here, one must consider the exposure opportunities posed by the woman’s residential environment, such as those involved with household tasks, those related to her pursuit of hobbies and those related to her ‘micro-environment,’ including diet.

Diet

Beyond the current recommendations related to healthy eating, the uses of non-prescription herbal or alternative medicines or supplements are crucial parts of the medical history for women planning a pregnancy. Also, some ethnic home remedies must be queried for, as some contain hazardous contaminants such as lead and mercury [6]. There are also several dietary cautions, which should be reviewed with the woman contemplating pregnancy. One is not new and relates to the warning regarding exposure to food borne listeria infections. Although listeriosis may cause only mild flu-like symptoms in the pregnant mother, serious outcomes in the fetus may result. These include premature delivery, stillbirth or neonatal infection [7–8]. General advice relies upon avoidance of soft cheese such as feta, Brie, Camembert, blue-veined and Mexican-style cheeses and unpasteurized milk or milk products [9]. Strict adherence to food preparation safety, such as vigilant washing of raw fruits and vegetables, avoidance of undercooked and raw meat and careful separation of stored raw food from uncooked meats serves to enhance safety for the entire family as most food borne illness is preventable.

Consumer advisory on methylmercury in fish

In 2004, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a joint consumer advisory on methylmercury in fish and shellfish. The warning specifically targets women who may become pregnant, are pregnant or are nursing mothers, and also includes young children. The document emphasizes the health benefits of fish in the diet generally as a good source of protein, and also warns of several types of fish which contain comparatively higher concentrations of mercury and should be avoided. These include: shark, swordfish, King mackerel and Tilefish. Other types of fish may be consumed in up to two meals (6 oz each) per week, including: shrimp, canned light tuna (but not albacore, which has more mercury), salmon, pollock and catfish. The Advisory also warns about local fish advisories, which are generally posted for specific populations which supplement their diets with locally, caught fish. Appropriate discussion of relevant advisories should take place in the preconception visit and is especially important for non-meat eating patients whose total dietary intake of fish may be relatively greater than is the case for meat consumers. Also of note, the U.S. Department of Health’s Women’s Infants, and Children Program (WIC) sometimes gives canned tuna as a diet supplement. This practice should be weighed in light of the above concerns, however, at least in terms of the relative amount of tuna in a weekly diet. The complete consumer advisory can be found at: www.epa.gov/ost/fish.

Hobbies and home-based work

The hobbies of concern generally would include those involving similar types of chemical toxicants discussed in the occupational section above, including heavy metals (lead, cadmium, arsenic) and solvents (paints (other than latex based), furniture stripper, metal cleaners etc.) Hobbies to be discouraged include: painting, ceramics, stained-glass window making (lead solder), furniture re-finishing and the like. Leisure activities to be avoided include use of saunas and hot tubs.

A number of home-based work activities, which resulted in contamination of the home and family members, have been documented in the literature. Although uncommon, they deserve mention here. At one end of the spectrum most involve the use of metals, either in metal parts reclamation (lead batteries being melted down) or jewelry making (heating and soldering) [10]. At the other, the home environment may be unwittingly contaminated by family members who bring work contaminants home on their shoes or dirty work clothes. If the work clothes are laundered at home, there not only is opportunity for exposure to the launderer but also other household members. For this reason, some OSHA standards require changing rooms so work clothes will not secondarily expose family members, in the case of lead and asbestos work, for example [11].

Household exposures

Pesticides, herbicides and rodenticides are likely the most common chemical toxicants in the average home. Certainly, a pregnant woman or one actively attempting to conceive, should not apply any of these [12]. Because the concept of ‘second hand’ exposure as described above applies here also, care needs be taken so that the chemicals are not ‘tracked’ into or throughout the house, no matter who performs the chemical applications. Of far greater importance on a population basis is second hand smoke in the home and/or workplace. Numerous polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons present in cigarette smoke are carcinogenic and have been shown to affect reproductive outcomes in animal studies. They cross and affect the placenta, and enter breast milk [13]. Laundering of contaminated work clothes is also a concern, as discussed above. A hiatus from caring for the family cat and litter box should be mentioned due to the toxoplasmosis risk.

Many non-latex paints are solvent based and contain small amounts of metals to enhance wear, and as preservatives. This is especially true of exterior paint, such as that used on porches or building exteriors or even in the interiors of older buildings. Rehabbing older homes, which often involve paint stripping, either with a heat gun or a chemical stripper is particularly hazardous. Inhalation is a very efficient means of producing a clinically significant exposure to lead which was commonly used years ago in interiors of homes. Many commercial paint strippers contain methylene chloride (dichloromethane), which metabolizes to carbon monoxide, and is particularly toxic to the fetus.

Guidance for clinician

Certainly, awareness that occupational and environmental hazards encountered by patients may play a clinically significant role in a pregnancy outcome is the first step in effective patient management. Therefore, enlarging the standard health history form, completed by the patient on or before the first visit to obtain a more detailed environmental history is a necessary first step and is also often very informative. Whereas a number of preconception checklists exist, only some of which address fish consumption or residence near a waste site, most poorly capture, or even fail to query about occupation, despite this being the likely greatest ‘environmental’ risk the patient faces.

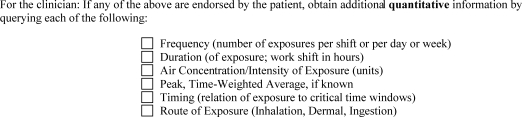

A ‘qualitative’ evaluation of a patient’s potential exposure to reproductive and developmental toxicants can be obtained with a screening questionnaire as seen in Fig. 1. This involves examining occupation by industry sector of employment and then by chemical, physical and biological agents of concern. If a reproductive hazard is present in the patient’s work environment, an initial quantitative assessment can be made regarding the exposure intensity (Fig. 2). However, at this point, the clinician may want to consult an occupational medicine colleague to elicit a more detailed history and assist in the preconception recommendations.

Fig. 1.

Example checklist for initial qualitative evaluation of reproductive hazards, (modified from Grajewski, 2005)

Fig. 2.

Example of checklist for initial quantitative evaluation of reproductive hazards, (modified from Grajewski, 2005)

Preconception management strategies, should be based on the occupational history and include a decision on the safety of continued employment during the preconception period and pregnancy. If the patient works with bona fide reproductive and development toxicants, continued employment and under what circumstances must be determined. This may involve identifying additional protections, such as a respirator, gloves or other personal protective apparel or equipment that may make the job safer for the patient. There are some jobs, however, where it is recommended by professional organizations as well as governmental safety and health agencies, that pregnant persons, or those actively trying to conceive be provided with alternative duty [14]. A good example here is nurses who handle cancer chemotherapy [15]. However, a related issue involves crafting elements of an existing job which the pregnant patient, such as the oncology nurse may safely continue, such as patient education, telephone triage and the like. This arrangement is termed ‘alternative duty’. Also involved in preconception counseling is the potential impact on the quality of breast milk if the mother is planning to breastfeed. The majority of organic solvents and pharmaceuticals absorbed by the mother in the workplace invariably make their way into milk. Thus, both work during pregnancy and return to work while breastfeeding need to be considered.

We have thus far focused on the working patient’s current job, which is generally considered the most influential on pregnancy outcome, as most reproductive toxicants are thought to act via an acute toxicity mechanism during the three to four months prior to conception and pregnancy [16–18]. However, there are also several examples of remote past exposure that are important to elicit, though likely less commonly encountered. An example includes the patient who has high bone lead stores from remote past (childhood) exposure that can be mobilized during pregnancy and expose the fetus [19–20]. Medical management at the preconception visit would include a blood lead level so this can be tracked during pregnancy. Also, maternal stores of fat-soluble organic chemicals, such as dioxins and PCBs may also expose the fetus [21, 22]. Positive responses to exposure to occupational or environmental agents by the preconception patient may require consultation. The Association of Occupational and Environmental Clinics can supply referrals to clinicians in various locales nationwide at (www.aoec.org).

Conclusion

The preconception office clinic visit presents a strategic opportunity to minimize the environmental and occupational sources of reproductive risk facing the preconception patient. This requires the two-way exchange of information between the patient and her clinician, clarifying misunderstandings and implementing reasonable strategies to minimize exposures from the wider community, in the workplace and at home. Taking an environmental and occupational history and tailoring recommendations based on that, enlarges the likelihood that preventable, adverse pregnancy outcomes can be avoided.

Reference

- 1.Institute of Medicine (IOM). Role of the primary care physician in occupational and environmental medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1988. [PubMed]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Committee report on curriculum development in environmental medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1992.

- 3.American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG). Ante Partam Record Plain paper Version Form #. Retrieved from Web www.acog.org/October 31, 2005.

- 4.Stellman JM. Where women work and the hazards they may face on the job. J Occup Environ Med. 1994;36(8):814–25. [PubMed]

- 5.GAO U.S. (Government Accounting Office). Reproductive and Developmental Toxicants, October 1991.

- 6.Riley DM, Newby CA, Leal-Almeraz TO, Thomas VM. Assessing elemental mercury vapor exposure from cultural and religious practices. Environ Health Perspect. 2001 Aug;109(8):779–84. UI: 11564612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Ogunmodede F, Jones JL, Scheftel J, Kirkland E, Schulkin J, Lynfield R. Listeriosis prevention knowledge among pregnant women in the USA. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Mar;13(1):11–5. UI: 16040322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Posfay-Barbe KM, Wald ER, Listeriosis. [Review] [87 refs] [Journal Article. Review. Review, Tutorial] Pediatrics in Review. 2004 May;25(5):151–9. UI: 15121906. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Danielsson-Tham ML, Eriksson E, Helmersson S, Leffler M, Ludtke L, Steen M, Sorgjerd S, Tham W. Causes behind a human cheese-borne outbreak of gastrointestinal listeriosis. Foodborne Pathogens Dis. 2004;1(3):153–9. UI: 15992274. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.McDiarmid MA, Weaver V. Fouling ones own nest revisited. Am J Ind Med. 1993;24:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). 29 CFR 1910.1025. The Lead Standard. 1978.

- 12.March of Dimes (MOD). Environmental Risks and Pregnancy, Quick References and Fact Sheet. Retrieved from web www.marchofdimes.com 10/31/05.

- 13.Institute of Medicine (IOM). Environmental medicine. In: Pop AM, Rall DP, editors. Integrating a missing element into medical education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1995. [PubMed]

- 14.American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM). Reproductive Hazard Management Guidelines 1994. Arlington Heights, Illinois. Retrieved from the web at www.acoem.org/guidelines/article.asp?ID=65

- 15.Oncology Nursing Society ONS. Chemotherapy and biotherapy guidelines and recommendations for practice. 2nd ed. Polovich M, White JM, Keller LO, editors. Pittsburgh, PA: Oncology Nursing Society; 2005.

- 16.Grajewski B, et al. Occupational exposures and reproductive health: 2003 teratology society meeting symposium summary. Birth Defects Res Part B-Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2005;74:157–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Selevan SG, Kimmel CA, Mendola P. Identifying critical windows of exposure for children’s health. Environ Health Perspectives. 2000;108(Suppl. 3):451–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Kimmel CA, Makris SL. Recent developments in regulatory requirements for developmental toxicology. Toxicology Lett. 2001;120(1–3):73–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Gulson BL, et al. Impact of diet on lead in blood and urine in female adults and relevance to mobilization of lead from bone stores. Environ Health Perspectives. 1999;107(4):257–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Brown MJ, et al. Determinants of bone and blood lead concentrations in the early postpartum period. Occupational Environ Med. 2000;57(8):535–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Muckle G, et al. Prenatal exposure of the Northern Quebec inuit infants to environmental contaminants. Environ Health Perspectives. 2001;109(12):1291–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Vreugdenhil HJI, et al. Effects of prenatal PCB and dioxin background exposure on cognitive and motor abilities in Dutch children at school age. J Pediatrics. 2002;140(1):48–56. [DOI] [PubMed]