Abstract

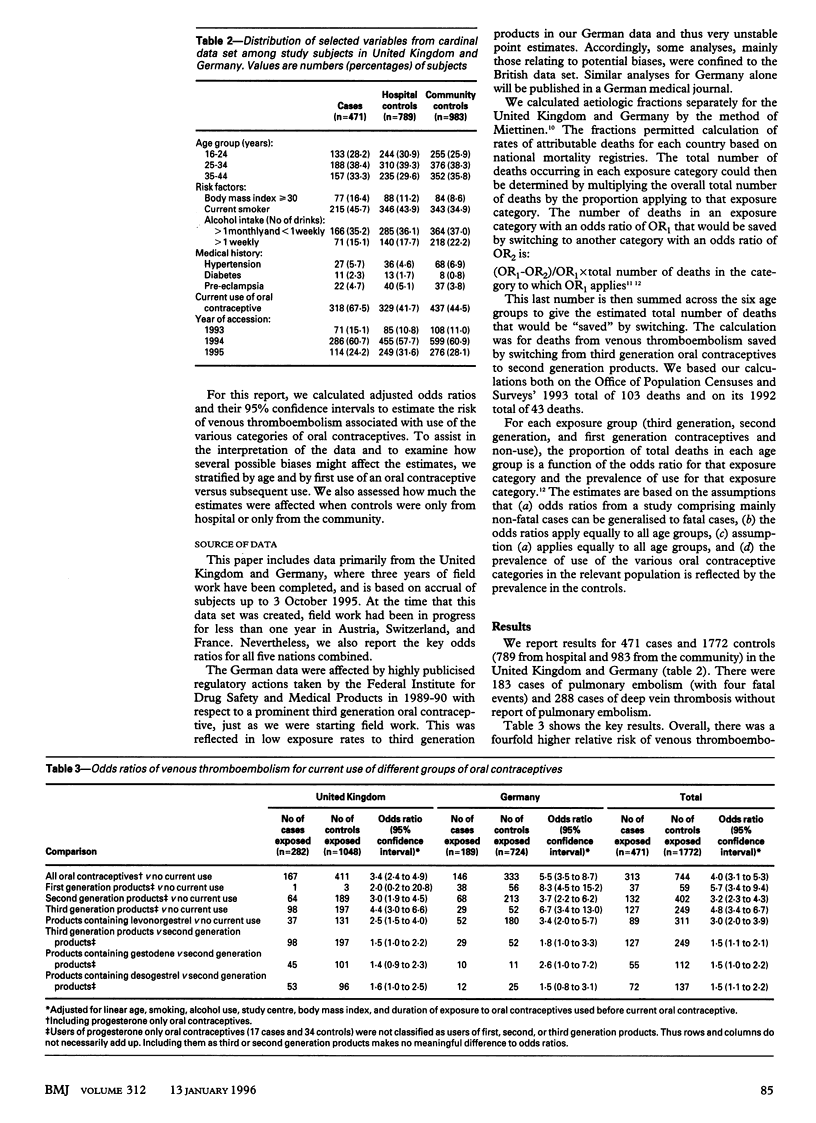

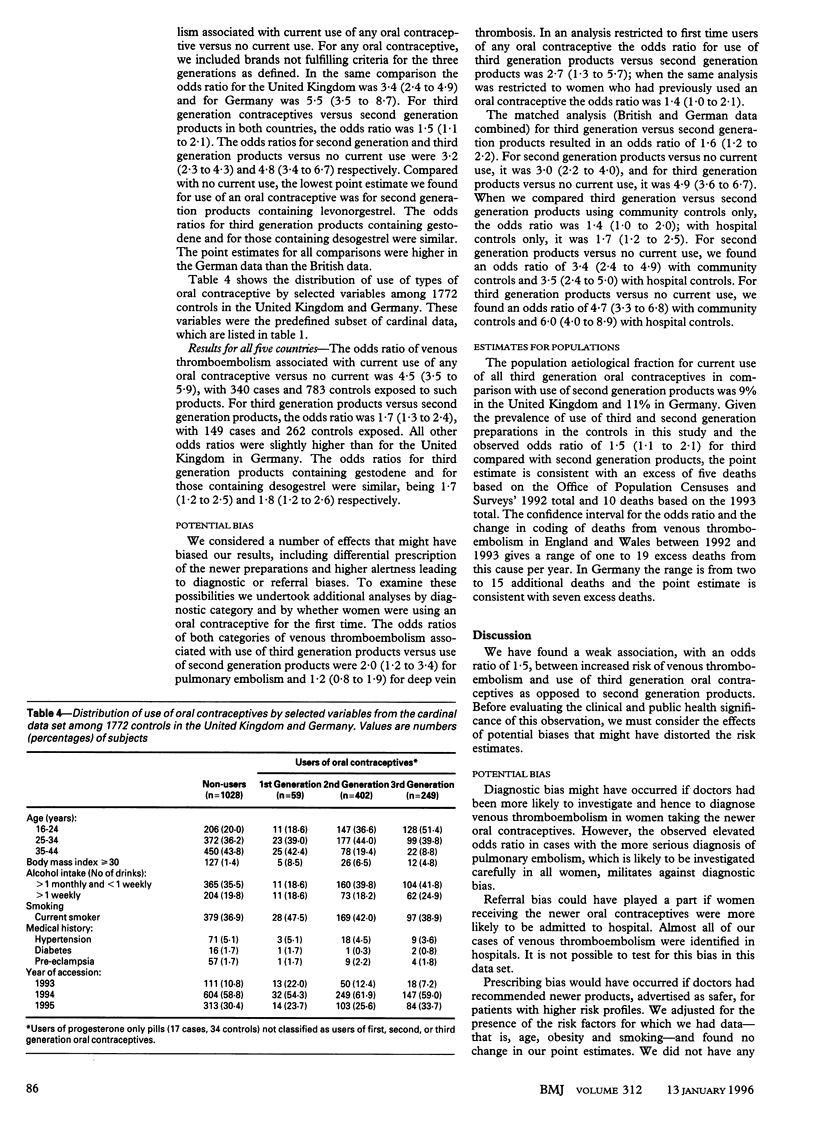

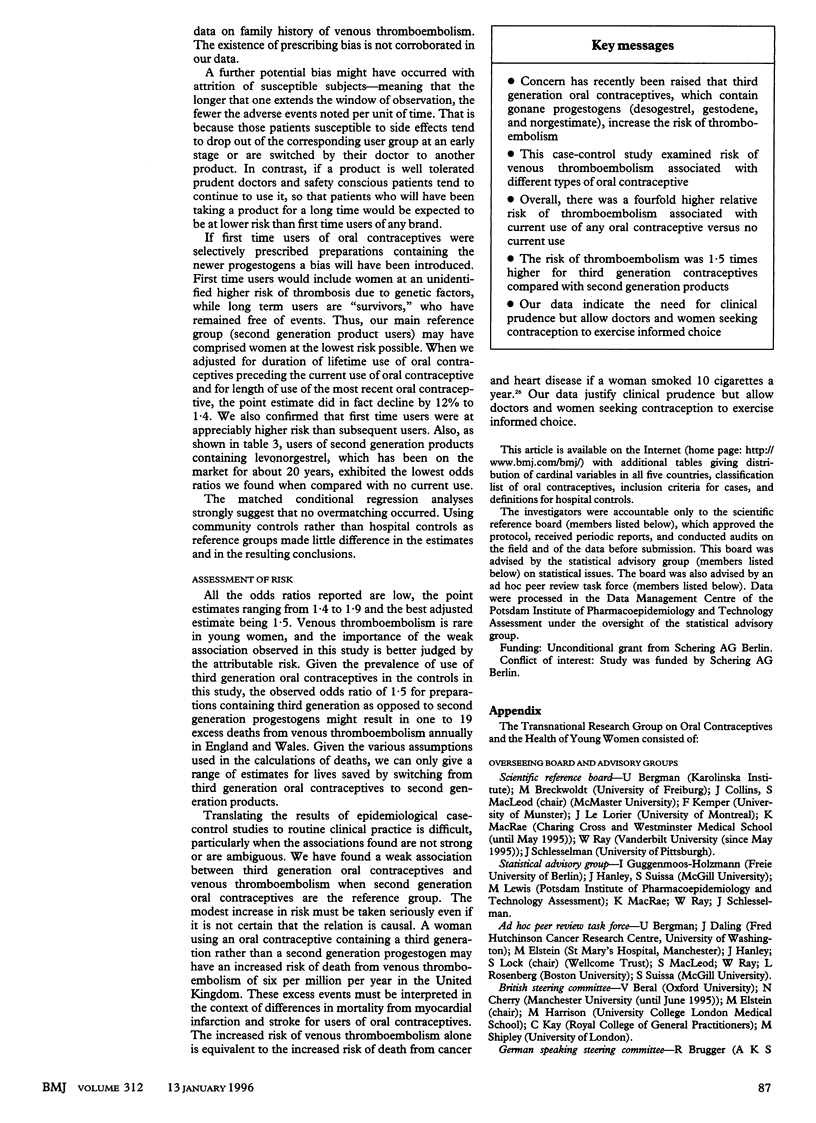

OBJECTIVE--To test whether use of combined oral contraceptives containing third generation progestogens is associated with altered risk of venous thromboembolism. DESIGN--Matched case-control study. SETTING--10 centres in Germany and United Kingdom. SUBJECTS--Cases were 471 women aged 16-44 who had a venous thromboembolism. Controls were 1772 women (at least 3 controls per case) unaffected by venous thromboembolism who were matched with corresponding case for age and for hospital or community setting. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Odds ratios derived with stratified analyses and unconditional logistic regression to adjust for potential confounding variables. RESULTS--Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for venous thromboembolism were: for any oral contraceptives versus no use, 4.0 (3.1 to 5.3); for second generation products (low dose ethinyl-oestradiol, no gestodene or desogestrel) versus no use, 3.2 (2.3 to 4.3); for third generation products (low dose ethinyloestradiol, gestodene or desogestrel) versus no use, 4.8 (3.4 to 6.7); for third generation products versus second generation products, 1.5 (1.1 to 2.1); for products containing gestodene versus second generation products, 1.5 (1.0 to 2.2); and for products containing desogestrel versus second generation products, 1.5 (1.1 to 2.2). Probability of death due to venous thromboembolism for women using third generation products is about 20 per million users per year, for women using second generation products it is about 14 per million users per year, and for non-users it is five per million per year. CONCLUSIONS--Risk of venous thromboembolism was slightly increased in users of third generation oral contraceptives compared with users of second generation products.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Cole P., MacMahon B. Attributable risk percent in case-control studies. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1971 Nov;25(4):242–244. doi: 10.1136/jech.25.4.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldzieher J. W. Advances in oral contraception. An international review of levonorgestrel and ethinyl estradiol. J Reprod Med. 1983 Jan;28(1 Suppl):53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung-Hoffmann C., Kuhl H. Interaction with the pharmacokinetics of ethinylestradiol and progestogens contained in oral contraceptives. Contraception. 1989 Sep;40(3):299–312. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(89)90094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl H., Jung-Hoffmann C., Heidt F. Alterations in the serum levels of gestodene and SHBG during 12 cycles of treatment with 30 micrograms ethinylestradiol and 75 micrograms gestodene. Contraception. 1988 Oct;38(4):477–486. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(88)90088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVIN M. L. The occurrence of lung cancer in man. Acta Unio Int Contra Cancrum. 1953;9(3):531–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen O. S. Proportion of disease caused or prevented by a given exposure, trait or intervention. Am J Epidemiol. 1974 May;99(5):325–332. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadel B. V. Oral contraceptives and cardiovascular disease (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1981 Sep 10;305(11):612–618. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198109103051104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessey M. P. Benefits and risks of combined oral contraceptives. Methods Inf Med. 1993 Apr;32(3):222–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]