Abstract

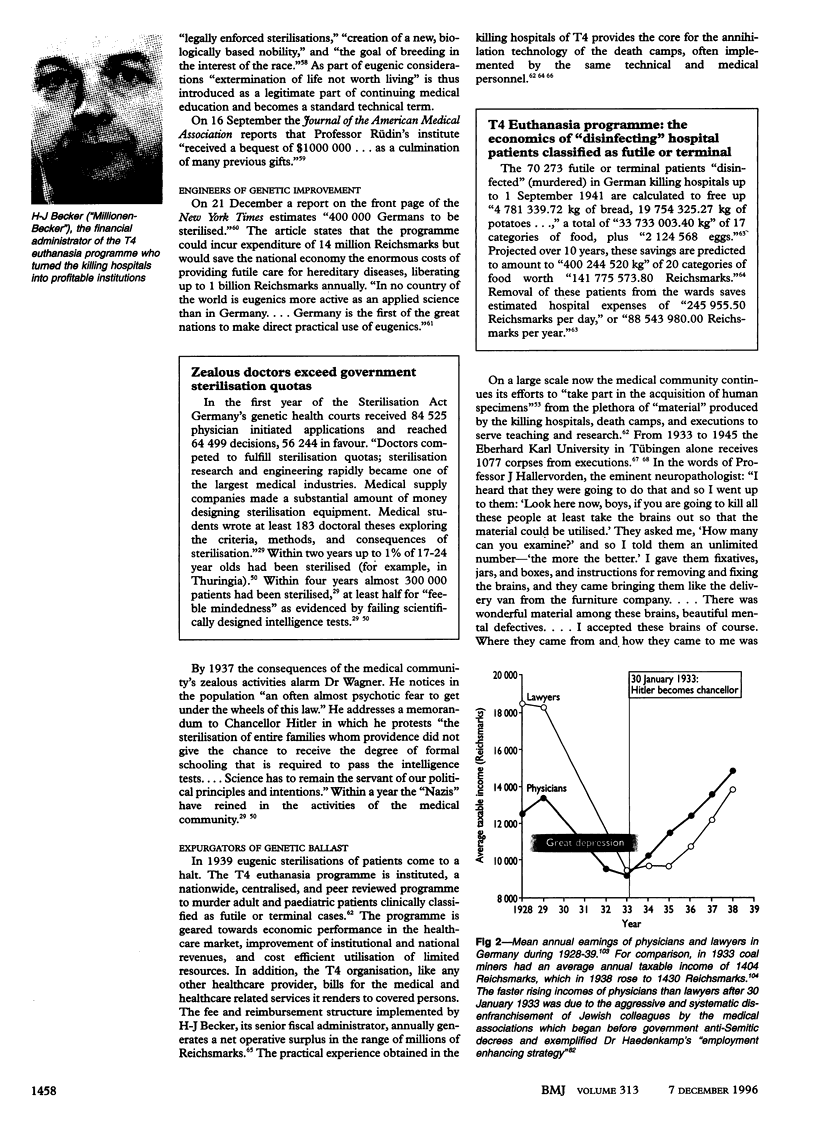

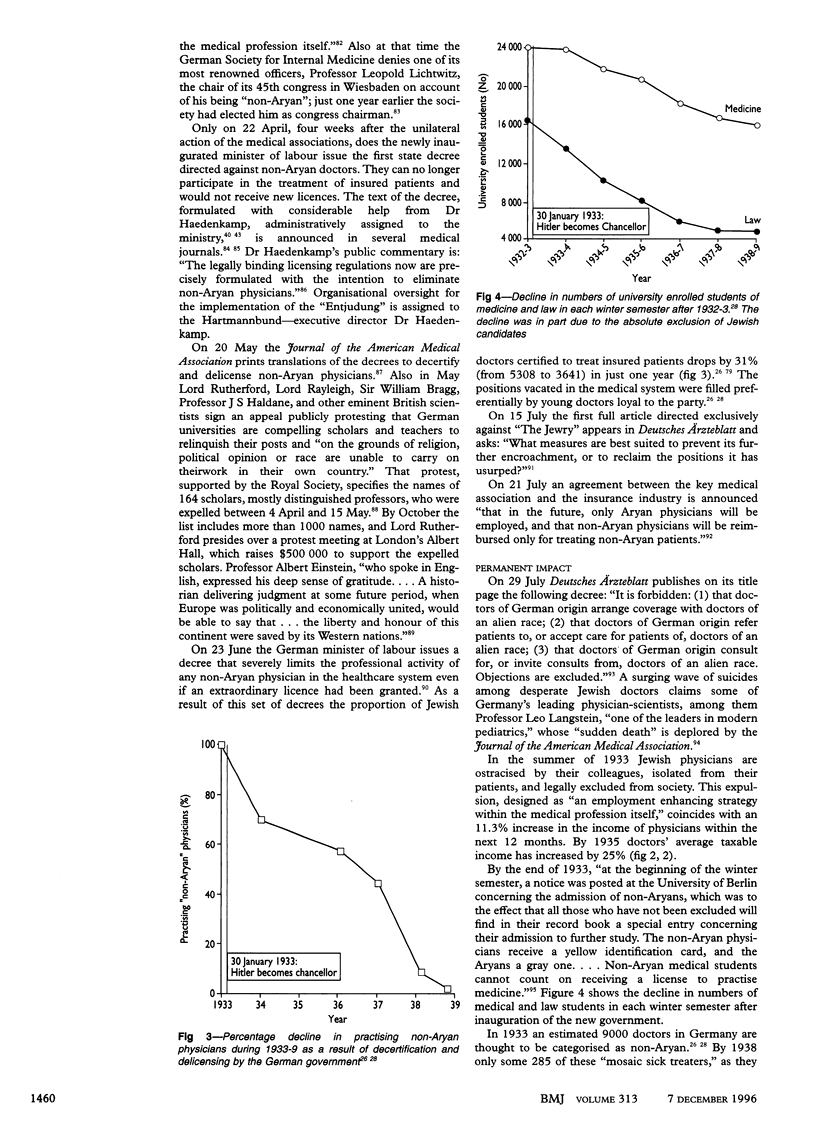

The history of medicine this century is darkened by the downfall of the German medical profession, exposed during the doctors' trial at Nuremberg in 1946. Relying largely on documents published during 1933 in German medical journals, this paper examines two widely accepted notions of those events, metaphorically termed "slippery slope" and "sudden subversion." The first connotes a gradual slide over infinitesimal steps until, suddenly, all footing is lost; the second conveys forced take over of the profession's leadership and values. Both concepts imply that the medical profession itself became the victim of circumstances. The slippery slope concept is a prominent figure of argument in the current debate on bioethics. The evidence presented here, however, strongly suggests that the German medical community set its own course in 1933. In some respects this course even outpaced the new government, which had to rein in the profession's eager pursuit of enforced eugenic sterilizations. In 1933 the convergence of political, scientific, and economic forces dramatically changed the relationship between the medical community and the government. That same convergence is occurring again and must be approached with great caution if medicine is to remain focused on the preservation of physical and medical integrity.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

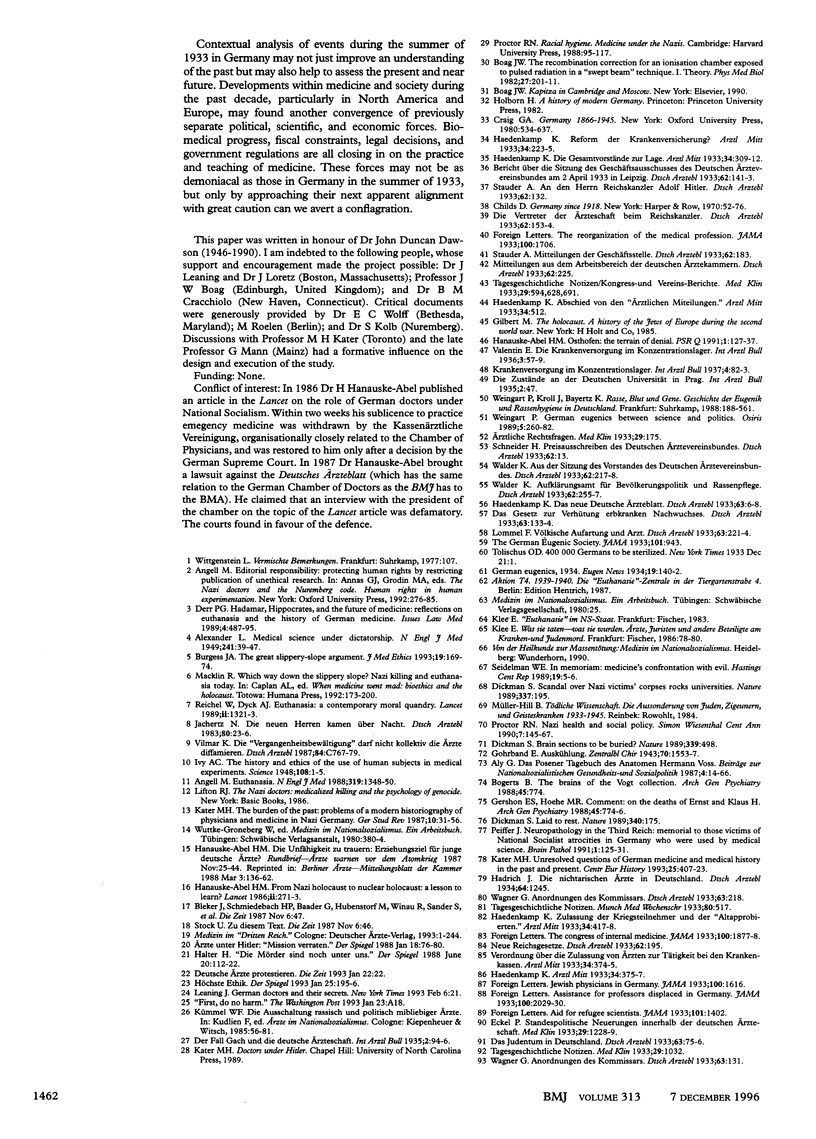

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ALEXANDER L. Medical science under dictatorship. N Engl J Med. 1949 Jul 14;241(2):39–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJM194907142410201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angell M. Euthanasia. N Engl J Med. 1988 Nov 17;319(20):1348–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811173192010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boag J. W. The recombination correction for an ionisation chamber exposed to pulsed radiation in a 'swept beam' technique. I. Theory. Phys Med Biol. 1982 Feb;27(2):201–211. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/27/2/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogerts B. The brains of the Vogt collection. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988 Aug;45(8):774–774. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800320092013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan A. Judging the past. The case of the human radiation experiments. Hastings Cent Rep. 1996 May-Jun;26(3):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess J. A. The great slippery-slope argument. J Med Ethics. 1993 Sep;19(3):169–174. doi: 10.1136/jme.19.3.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cut-price fingerprints. Nature. 1989 Jul 20;340(6230):175–175. doi: 10.1038/340175c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derr P. G. Hadamar, Hippocrates, and the future of medicine: reflections on euthanasia and the history of German medicine. Issues Law Med. 1989 Spring;4(4):487–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman S. Brain sections to be buried? Nature. 1989 Jun 15;339(6225):498–498. doi: 10.1038/339498c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman Steven. Scandal over Nazi victims' corpses rocks universities. Nature. 1989 Jan 19;337(6204):195–195. doi: 10.1038/337195a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden R. The Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments. Reflections on a Presidential Commission. Hastings Cent Rep. 1996 Sep-Oct;26(5):5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivy A. C. The History and Ethics of the Use of Human Subjects in Medical Experiments. Science. 1948 Jul 2;108(2792):1–5. doi: 10.1126/science.108.2792.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kater Michael H. The burden of the past: problems of a modern historiography of physicians and medicine in Nazi Germany. Ger Stud Rev. 1987 Feb;10(1):31–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCally Michael, Cassel Christine, Kimball Daryl G. U.S. government-sponsored radiation research on humans 1945-1975. Med Glob Surviv. 1994 Mar;1(1):4–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiffer J. Neuropathology in the Third Reich. [Memorial to those victims of National-Socialist atrocities in Germany who were used by medical science]. Brain Pathol. 1991 Jan;1(2):125–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1991.tb00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel W., Dyck A. J. Euthanasia: a contemporary moral quandary. Lancet. 1989 Dec 2;2(8675):1321–1323. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91921-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidelman W. E. In memoriam: medicine's confrontation with evil. Hastings Cent Rep. 1989 Nov-Dec;19(6):5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevell M. I., Evans B. K. The "Schaltenbrand experiment," Würzburg, 1940: scientific, historical, and ethical perspectives. Neurology. 1994 Feb;44(2):350–356. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevell M. Racial hygiene, active euthanasia, and Julius Hallervorden. Neurology. 1992 Nov;42(11):2214–2219. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.11.2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingart P. German eugenics between science and politics. Osiris. 1989;5:260–282. doi: 10.1086/368690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]