Abstract

Bacterial outer membrane porins have a robust β-barrel structure and therefore show potential for use as stochastic sensors based on single-molecule detection. The monomeric porin OmpG is especially attractive compared with multisubunit proteins because appropriate modifications of the pore can be easily achieved by mutagenesis. However, the gating of OmpG causes transient current blockades in single-channel recordings that would interfere with analyte detection. To eliminate this spontaneous gating activity, we used molecular dynamics simulations to identify regions of OmpG implicated in the gating. Based on our findings, two approaches were used to enhance the stability of the open conformation by site-directed mutagenesis. First, the mobility of loop 6 was reduced by introducing a disulfide bond between the extracellular ends of strands β12 and β13. Second, the interstrand hydrogen bonding between strands β11 and β12 was optimized by deletion of residue D215. The OmpG porin with both stabilizing mutations exhibited a 95% reduction in gating activity. We used this mutant for the detection of adenosine diphosphate at the single-molecule level, after equipping the porin with a cyclodextrin molecular adapter, thereby demonstrating its potential for use in stochastic sensing applications.

Keywords: gating, MD simulation, OmpG, stochastic sensor

Engineered protein pores can be used as stochastic sensors for single-molecule detection (1). The ionic current flowing through a pore under an applied potential is altered when an analyte binds within the lumen (1). Measurement of the frequency of occurrence of the binding events allows the determination of the concentration of an analyte, while the nature of the events (e.g., their amplitude or duration) aids in analyte identification. To date, studies of proteinaceous stochastic sensing elements have mostly focused on staphylococcal α-hemolysin (αHL), a β-barrel pore-forming toxin (1, 2). However, the stoichiometry and symmetry of the heptameric αHL pore generate a large number of combinations and permutations when more than one type of subunit is used (3), which makes it difficult to fine-tune the properties of the pore. Therefore, it would be highly desirable to design a stochastic sensor based on a monomeric β-barrel.

OmpG is a monomeric porin from the outer membrane of Escherichia coli that presents an attractive alternative to αHL for stochastic sensing (4–7). Previous studies have shown that OmpG undergoes pH-dependent, voltage-dependent, and spontaneous gating (4, 5). Specifically, the pore tends to close when the pH decreases to below 7 or when the voltage is higher than ±100 mV (5). At neutral pH and an applied potential lower than ±100 mV, OmpG exhibits a spontaneous gating behavior—i.e., it rapidly switches between open and closed states (Fig. 1A). Such spontaneous gating interferes with the application of a pore as a biosensor. Therefore, eliminating or significantly reducing the intrinsic gating activity of OmpG would be an important step in the development of an alternative to αHL.

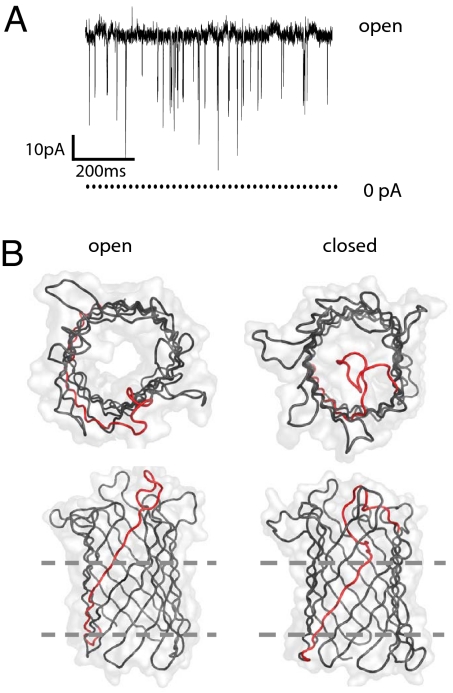

Fig. 1.

Open and closed structures of OmpG. (A) Single-channel current recording of OmpG in a planar bilayer. The cis and trans chambers both contained 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.5)/1 M KCl. Protein was added to the cis chamber, and recordings were made at +50 mV. (B) Top and side view of OmpG in the open and closed states. Structures were created according to Protein Data Bank entries 2IWW (closed) and 2IWV (open). Loop 6 (L6) and strand β12 are highlighted in red. Dashed lines indicate the proposed position of the phosphates in the lipid head groups of the bilayer.

The x-ray and NMR structures of OmpG (6–8) reveal that, like the heptameric αHL, OmpG has a 14-stranded β-barrel architecture. The strands are connected by long loops on the extracellular side and short turns on the periplasmic side of the outer membrane. The structures determined by Kuhlbrandt's group show that OmpG adopts an open conformation at neutral pH (pH 7.5), whereas at acidic pH (pH 5.6) it is closed (Fig. 1). In the closed state, strand β12 is partly unfolded to extend loop 6 (L6), which in turn folds into the barrel lumen and occludes the pore (Fig. 1). We hypothesized that the flexibility of L6 and strand β12 might be responsible for most of OmpG's spontaneous gating activity. Therefore, we developed a twofold approach to stabilizing the positions of strand β12 and L6 in an open conformation. First, a disulfide bond was created between strands β12 and β13 by introducing cysteine residues at positions G231 and D262, which are located at the extracellular ends of strands β12 and β13, respectively [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. The oxidized form of this protein will be referred to as S-S and the reduced form as SH-SH. Second, all three x-ray structures of OmpG reveal a bulge in strand β11 at residues L214 and D215 (Fig. S1) (6, 7). The side chains of these adjacent residues point in the same direction, rather than in opposite directions, which causes a mismatch in hydrogen bonding between strands β11 and β12. Therefore, we optimized the hydrogen bonding by deleting residue D215. The wild-type protein and the mutants were characterized by molecular dynamics simulations and single-channel electrical recording. Gating was reduced in both mutants and therefore they were combined in a double mutant (S-S/ΔD215), which was fitted with a molecular adapter, heptakis-(6-deoxy-6-amino)-β-cyclodextrin (am7βCD), and tested as a sensor for the detection of ADP.

Results

Molecular Dynamics (MD).

MD simulations of the wild-type protein, in the open and closed conformations (Protein Data Bank entries 2IWV and 2IWW, respectively) and of the S-S and ΔD215 mutants were performed for 10 ns. Models of the mutants were created by aligning the mutant sequence with the wild-type sequence and then threading this onto the open-conformation x-ray structure (2IWV) as a template. The ΔD215 mutant was generated by homology modeling using MODELLER. In all simulations, the ionizable protein residues were modeled in their default states at pH 7. In each simulation, the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the Cα atoms from the starting structure at t = 0 ps rose steadily before reaching a plateau value after ≈3 ns, indicating that the simulations had equilibrated. Following the general pattern seen in MD simulations of other outer membrane proteins (9), the structural drift was greatest for the extracellular loops and lowest for the transmembrane barrel regions. The RMSD of the β-barrel regions, in the wild-type and mutant simulations, had plateau values of ≈1.3 Å after 10 ns.

Principal Components Analysis.

Principal components analysis enables the isolation of global concerted motions from local conformational fluctuations. We have analyzed the motion described by eigenvector 1—i.e., the lowest frequency motion—for each simulation by calculating the two extreme projections of the eigenvector on the time-averaged structure and then interpolating between these extremes. In each case, the motion is dominated by L6. The dominant motion of L6 in 2IWW (closed), S-S, and ΔD215 is a movement away from the barrel mouth (Fig. 2). In contrast, the dominant motion of L6 in 2IWV (open) is toward the mouth of the barrel.

Fig. 2.

Principal component analysis. The motion of L6 as described by eigenvector 1 from principal components analysis (other motion has been omitted). The protein backbone is shown in tube representation (black). The motion of L6 is depicted by extrapolating between the two extreme projections described by eigenvector 1 and then overlaying the conformation of the loop after every 40 ps (each simulation has a total time of 10 ns). The RGB color scheme is used with red representing the start of the simulation. L6 is clearly moving toward the interior of the barrel in 2IWV. In contrast, L6 in D215 and S-S (models built based on the open structure 2IWV) move away from the lumen. In 2IWW, L6 is moving out from the center of the barrel.

Pore Dynamics.

Pore diameter profile analysis [using HOLE (10)] revealed that after the 10-ns simulations, the mutant pores in general are wider than wild-type pores. We calculated the pore diameter profiles of both crystal structures used to initiate the wild-type simulations (2IWW and 2IWV) and compared them with the average pore profiles over the last 200 ps of each simulation (Fig. 3). As expected, the main differences in the diameter are at the extracellular ends of the pores. The pore diameter in the x-ray structure of the closed protein (2IWW) is only ≈1.4 Å at its narrowest point, which is too narrow to allow the passage of hydrated ions. This constriction is caused by the collapse of strand β12 and the folding of L6 into the lumen of the β-barrel. In contrast, the narrowest region of the pore in the open-conformation structure (2IWV) is ≈8.0 Å and hence sufficiently wide for the passage of hydrated ions. The pore profiles averaged over the last 200 ps of the simulations reveal that by the end of the simulations of the wild-type proteins, the diameter of the open conformation has been reduced from ≈8.0 to ≈4.2 Å at the narrowest point, whereas the diameter of the closed conformation has increased from ≈1.4 to ≈6.0 Å. This dynamic behavior of the pore—i.e., widening and narrowing at the extracellular mouth of the barrel—arises largely from the motion of L6 as discussed above. It is interesting that the narrowest regions in the pore in the two simulations of the wild-type are at slightly different locations within the barrel. The location of the ≈4.2-Å-diameter constriction in the 2IWV pore after 10 ns of simulation is at the mouth of the barrel, whereas the ≈6.0-Å-diameter constriction in the 2IWW pore is located slightly nearer the center of the barrel. This difference can be explained by examining the nature of the constrictions. In 2IWW, before the simulation, the constriction is formed by the collapse of strand β12 and the folding of L6 into the lumen of the barrel. Although movement of L6 out of the pore is observed in 2IWW after the simulation, strand 12 remains folded into the pore and a significant constriction remains. The constriction in 2IWV after simulation is due only to the folding of L6 into the pore and hence is located at the mouth of the barrel. The collapse of strand β12 is not observed on this time scale. After simulation, S-S remained in the open conformation. Indeed, the pore diameter is >8 Å in the narrowest region after 10 ns of simulation—i.e., the pore is wider than that in the x-ray structure of the open conformation. At the end of the simulation, the ΔD215 pore is narrower than the S-S pore after simulation and the 2IWV x-ray structure but wider than both the 2IWW and 2IWV pores (after simulation).

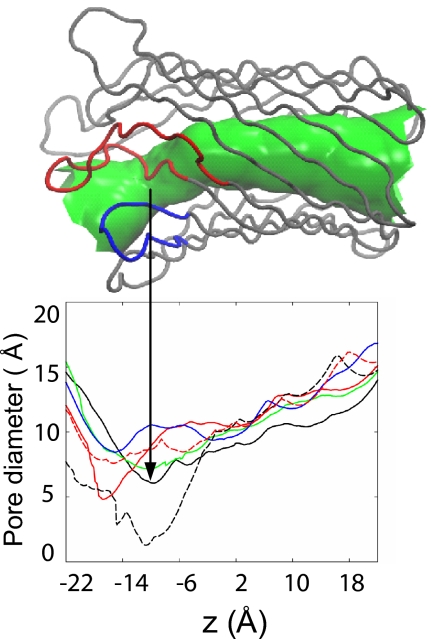

Fig. 3.

Pore profiles. The pore diameters of the open (red, dashed line) and closed (black, dashed line) crystal structures before the simulation, differ by up to ≈4 Å at the extracellular side. After 10 ns of simulation, these differences are less marked; in fact, motion of L6 toward the mouth of the barrel in the initially open 2IWV (red, solid line) results in a narrower pore than the initially closed 2IWW (black, solid line). The pore diameters in ΔD215 (green) and S-S (blue) after 10 ns are wider than both of the wild-type proteins at the end of the simulations. The surface representation of the pore (green) corresponds to the 2IWW radius profile and provides a visual aid in identification of the various regions of the pore.

Hydrogen Bonding.

The x-ray structures of OmpG in the open (2IWV) and closed (2IWW) conformations and analysis of the conformational dynamics of the pores from MD simulations of the wild-type protein and mutants implicated loop L6 and strand β12 in the spontaneous gating of OmpG. We have analyzed the pattern of hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) in these regions in an attempt to understand how OmpG might be stabilized in an open conformation. During the simulations of the wild-type protein, there are ≈10 ± 2 H-bonds (average number ± standard deviation over 10 ns of simulation time) between strands β10 and β11 in both simulations and ≈12.0 ± 2.5 H-bonds between strands β11 and β12 in the simulation of 2IWV (open), compared with only ≈9.0 ± 2.5 in 2IWW (closed). This suggests a correlation between the higher number of β11/β12 H-bonds and the openness of the pore. Thus, in the closed state, strands β11 and β12 are unable to form their full complement of H-bonds because β12 is folded into the interior of the β-barrel. The number of H-bonds between strands β10 and β11 in S-S is similar to that in the simulations of the wild type, but for strands β11 and β12 the number is similar to that of 2IWW. The number of H-bonds between strands β10 and β11 and strands β11 and β12 in ΔD215 is ≈13.0 ± 2.6 for both, indicating that the removal of D215 allows formation of a greater number of interstrand H-bonds.

Table 1.

Average number of H-bonds in wild-type and OmpG mutants during the 10-ns simulations

| Simulation | Average number of H-bonds |

|

|---|---|---|

| Strands 10–11 | Strands 11–12 | |

| 2IWW | 10.2 ± 2.1* | 9.5 ± 2.5 |

| 2IWV | 9.9 ± 2.1 | 12.2 ± 2.5 |

| S-S | 9.5 ± 2.3 | 9.6 ± 2.4 |

| ΔD215 | 13.2 ± 2.7 | 13.5 ± 2.7 |

*The average and SD was calculated from the number of H-bonds in each frame of the 10-ns simulation.

Single-Channel Recording of OmpG Variants.

All OmpG variants were expressed in inclusion bodies in E. coli and purified by ion-exchange chromatography. After the proteins had been refolded (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S2), single-channel current recording was performed. The OmpG mutants exhibited unitary conductance values of ≈1.2 nS in the fully open states (Table S1), which is similar to that of the monomeric wild-type pore (4–7). This indicates that the mutants insert into the lipid bilayer as monomeric pores and that the overall structure is not affected by the mutations described here. Based on the pattern of gating, we observed that all variants of OmpG can insert into the lipid bilayer in either orientation—i.e., the extracellular domain can be located in either the cis or the trans chamber—when the protein is added to the cis side. The pattern of the gating noise in the single-channel recordings is asymmetric with respect to the polarity of the applied potential—i.e., one current trace is always quieter than the one acquired at the opposite potential (Figs. S3–S6). We named the orientation in which the pore shows a quieter trace (Q-trace) at negative potential as “heads up,” with the other orientation as “tails up.” Following this definition, typical Q-trace recordings for all of the mutants in the “heads up” orientation are shown (Fig. 4A). In comparison with the wild type, S-S shows a reduced level of gating at −50 mV as indicated by the lower number of current spikes (Fig. 4A). Cleavage of the disulfide bond by the addition of DTT (to yield SH-SH) transforms the protein into a noisier pore, indicating that it is the presence of the disulfide bond rather than the cysteine residues that is responsible for the reduction in gating events. Fewer gating events were also observed with the ΔD215 mutant.

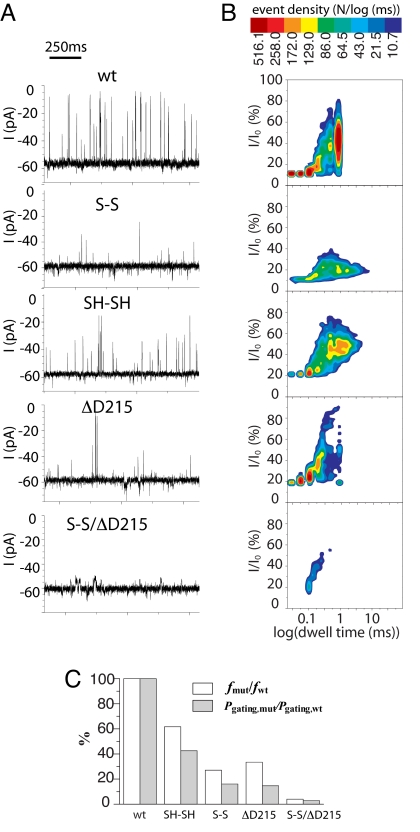

Fig. 4.

Reduced gating noise in the mutant OmpG pores. (A) Single-channel recordings of wild-type and mutant OmpG pores. Typical Q-traces (1 s) for each mutant in the “heads up” orientation are shown. Each chamber of the recording apparatus was filled with 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.5)/1 M KCl. The applied potential was −50 mV. Proteins were added to the cis chamber. In the case of the cysteine mutants, the oxidized form (S-S) was examined first. Afterward, DTT (10 mM, final) was added to both chambers to reduce the disulfide bridge and form SH-SH. (B) Corresponding 2D event-distribution plots associated with wild-type OmpG and various mutants. The distribution of gating events for 100 s of recording time is plotted according to the event amplitudes and dwell times. The amplitude (I) is the current change of an event relative to the current at the fully open state (I0). The density of events at each coordinate is indicated by the color code. (C) Comparison of gating activities of wild-type and mutant OmpG. The relative gating frequency f and Pgating of OmpG mutants are calculated taking the f and Pgating of wild-type OmpG as 100%.

To quantitatively evaluate the effect of the mutations on gating, two parameters are introduced: (i) the gating frequency (f, events/s), defined as the total number of gating events divided by the recording time; and (ii) the gating probability (Pgating), defined as the total time for which a pore is in the gated state (closed or partially closed) divided by the total recording time (all states). The former is a direct measure of the gating activity of the pore, whereas the latter describes the equilibrium between the closed and open states. The gating properties derived from the Q-traces of each OmpG variant are summarized (Fig. 4C and Table S2). In both S-S and ΔD215, the gating frequency (f) was decreased to 27% and 34% of the wild-type values, respectively (Fig. 4C). Breaking the disulfide bridge (to give SH-SH) increased f by 2-fold to 60% of the wild-type value (Fig. 4C). A shift in the gating equilibrium (Pgating) toward the value for the open state was also observed for ΔD215 and S-S. In the case of ΔD215, the improved H-bonding drives the equilibrium toward the open state by 7-fold. Because of the presence of a few very long duration events in the recordings of S-S, this mutant had a similar Pgating to ΔD215, although it closed less frequently than ΔD215.

Although both mutations (S-S and ΔD215) reduce gating, they have different effects on two characteristics of the gating events: the amplitude of the current block and the duration of the current block (mean dwell time) (Fig. 4B). For the wild-type protein, the gating amplitude ranges from 12% to 85% current block and the dwell time of the events ranges from 30 μs to 1 ms. The introduction of a disulfide bond between β-strands 11 and 12 (S-S) greatly decreased the amplitude of the events (<40% current block). When the disulfide bond is reduced (SH-SH), the amplitude of the gating events increases. These data indicate that the disulfide bond reduces the flexibility of strand 12, which, we propose, is responsible for high amplitude current blockades. Disulfide formation had little effect on the dwell time of the gating events. However, ≈2.5% of the events in the current traces of S-S have a long duration (τ > 10 ms) and were absent in the recordings of the wild type. In contrast to S-S, events with a high magnitude of current block are observed with the ΔD215 mutant, while the mean dwell time of the events is reduced. Notably, the events with high current block and a long dwell time seen in recordings with wild-type OmpG are greatly diminished in the 2-D (current block versus dwell time) events distribution plot of ΔD215. The plot also reveals that the events with a low magnitude of current block and short dwell times are not affected by the ΔD215 mutation. This result is consistent with the simulation data because the deletion of D215 enhances the H-bonding between strands β11 and β12. Therefore, the long current blocking events, which most likely require more extensive unfolding of strand β12, become unfavorable because such a conformational change requires the breaking of an additional approximately two H-bonds. The short, low-block events, which are present in the 2-D events distribution plot, probably require the breaking of fewer hydrogen bonds (Fig. 4B).

We combined the two mutations to create a double mutant (S-S/ΔD215), in an attempt to further reduce the gating noise. After adding this “double lock” to the gating strand β12, the gating signals were further diminished (Fig. 4). The gating frequency f in S-S/ΔD215 was <4% of the value for the wild-type pore and Pgating shifted toward the open state by a factor of ≈30 (Fig. 4C and Table S2). The events distribution plot shows that the majority of gating events are restricted to a zone with low current block (<60%) and short duration time (<0.6 ms) (Fig. 5). Therefore, our strategy produced a quiet protein pore (named qOmpG) that might be used to resolve analyte binding events with durations of >0.6 ms or high amplitude block >60% without compromise.

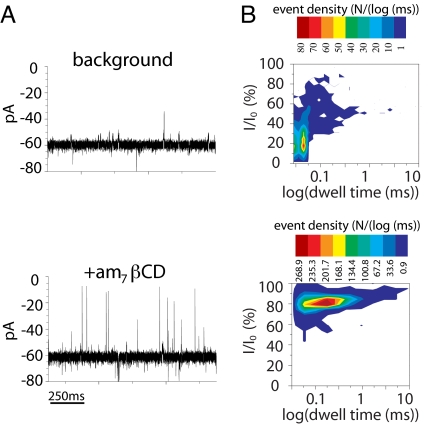

Fig. 5.

Interaction of am7βCD with the qOmpG pore. (A) A single qOmpG pore recorded with and without the addition of 1 μM am7βCD in buffer containing 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.5)/1 M KCl. The applied potential was −50 mV. (B) 2D event-distribution plots derived from current recordings over 500 s of recording time in the presence or absence of am7βCD.

Stochastic Detection of ADP by qOmpG·am7βCD.

Cyclodextrins (CDs) have been established as adapters for the αHL pore, allowing the detection of a wide variety of organic molecules through stochastic sensing (11, 12). We tested the ability of qOmpG to bind heptakis-(6-deoxy-6-amino)-β-cyclodextrin (am7βCD) (13). am7βCD is a positively charged β-cyclodextrin derivative in which the seven primary hydroxyl groups are replaced with amino groups. After a single qOmpG insertion had occurred, the current was recorded for 10 min at ±50 mV to provide the background level of events arising from gating of the pore (Fig. 5). Next, am7βCD was added to the cis chamber with the pore in the “heads up” orientation, and current recordings were performed at −50 mV. The addition of am7βCD caused reversible partial blockades of the ionic current passed by qOmpG (Fig. 5A). At −50 mV, the unitary conductance was reduced from 1.21 ± 0.06 nS (qOmpG) to 0.24 ± 0.02 nS (qOmpG·am7βCD) (Fig. 5A). The 2-D events distribution plot revealed a single population of events with ≈80% current block, which suggests that there is only one binding site for am7βCD within the qOmpG lumen (Fig. 5B). The dwell time histogram of the am7βCD binding events constructed after recording at an applied potential of −100 mV can be fitted to a single exponential function yielding a mean dwell time of 1.6 ± 0.3 (n = 3) ms, which is comparable with the lifetime of the αHL·βCD complex used for analyte detection (12). Therefore, we examined whether the qOmpG pore might be used to detect ADP. Because ADP is negatively charged, it was added to the trans chamber. In the absence of the analyte, the current exhibited two levels, open and blocked by am7βCD (Fig. 6B). The addition of ADP caused a further ≈16 pA of current block on top of the am7βCD binding events (Fig. 6C). The residence time of the ADP was 0.42 ± 0.02 ms (n = 3). Thus, the signal block can be used to identify and quantify ADP (1).

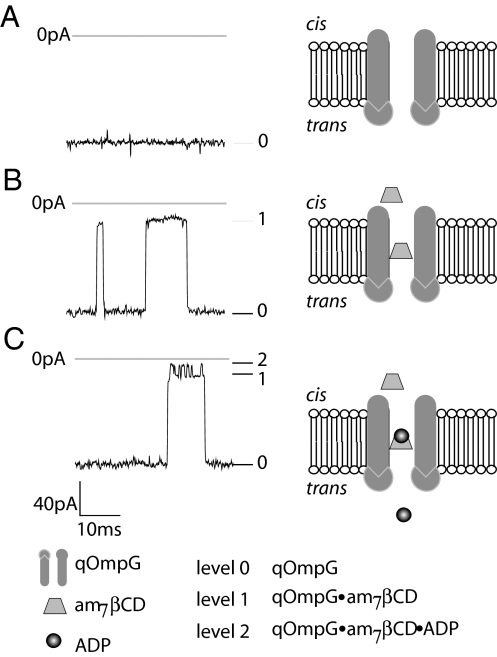

Fig. 6.

Detection of ADP with the qOmpG·am7βCD complex. The current recording shows the interaction of am7βCD and ADP with a single qOmpG pore inserted in the “heads up” orientation recorded at −100 mV in 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.5)/1 M KCl. am7βCD (1 μM final) was added to the cis chamber and ADP (5 mM final) was added to the trans chamber. (A) A single OmpG S-S/ΔD215 pore, −125 pA (level 0). (B) am7βCD binding to S-S/ΔD215 produces transient partial blockades of the channel, −20 pA (level 1). (C) ADP binding to am7βCD produces additional blockades, −4 pA (level 2).

Discussion

Potential of OmpG as a Biosensor.

qOmpG has the potential to become the first monomeric stochastic sensing pore. We show here that qOmpG, in combination with a molecular adapter, can be used to detect ADP. The utility of qOmpG as a sensor might be expanded by tailoring the properties of the pore and by the selection of different molecular adapters (14, 15). Furthermore, protein nanopores are currently being investigated for their utility in sequencing single molecules of DNA (13, 16–19). When a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) is electrophoresed through a pore, such as heptameric αHL, its sequence might be read from fluctuations in the ionic current characteristic of each of the four bases. However, in contrast to αHL, the monomeric structure of OmpG would allow complex patterns of amino acid side chains to be introduced more readily into the lumen of the pore to facilitate DNA sequencing. For example, positive charges could be placed along one side of the β-barrel to align the DNA backbone, leaving the other side of the pore available for base reading. An alternative sequencing method might also benefit from the quiet monomeric porin (13). By attaching an exonuclease to a protein pore, the nucleoside monophosphates cleaved by the enzyme might be read one base at a time (13). A qOmpG-based nanopore with an exonuclease attached should be easier to prepare than αHL hetero-heptamers containing a single exonuclease.

MD was applied to identify factors implicated in the gating activity of OmpG, which we then verified by single-channel recording experiments. MD greatly accelerated the discovery of pores with reduced noise, avoiding a random mutagenesis and screening process. This synergistic approach could help to remove the remaining noise associated with qOmpG and aid in the introduction of specific analyte detection sites. Again, by combining MD and single-channel recording, the qOmpG pore might become a useful model system with which to gain insights into important biological processes, such as transmembrane polymer translocation (e.g., DNA and polysaccharides) or nutrient uptake (e.g., sugars and amino acids).

Spontaneous Gating Mechanism of OmpG.

The mechanisms governing the spontaneous gating of β-barrel porins are complex and vary from porin to porin. Outer membrane protein A (OmpA) from E. coli contains eight β strands forming a small pore ≈15 Å in diameter (measured from Cα to Cα) (20–22). The gating of OmpA is associated with breaking and rearrangement of the salt bridges in the center of the barrel (21, 23). In the case of the trimeric porin OmpC, it has been proposed that spontaneous gating is related to the positioning or flexibility of loop 3, which folds to form an eyelet (constriction zone) within the pore (24, 25). It has been previously suggested that, under acidic conditions, L6 is implicated in the pH-dependent gating of OmpG (7). However, our results indicate an additional explanation for the role of this loop in the gating. Because both MD simulations and single-channel recording experiments (performed at pH 7.0 and 8.5, respectively) reveal a strong correlation between the gating activity and the mobility of strand β12 and L6, we believe that conformational changes of these regions are responsible for the majority of the spontaneous gating of OmpG. It is noteworthy that loop 3 is also related to voltage-dependent gating in the trimeric porin family (26–28). Thus, strand β12 and L6 may also play a role in the pH-gating and/or voltage-gating of OmpG; further work will be required to address this issue.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that conformational changes of strand β12 and L6 in OmpG play major roles in spontaneous gating. By reducing the mobility of strand β12 through mutagenesis and disulfide bond formation, we were able to greatly attenuate the gating of OmpG and make a quiet protein nanopore. Furthermore, the engineered pore was fitted with a molecular adapter, am7βCD, to detect ADP.

Methods

Molecular Simulations.

Homology models of the mutants were built by using MODELLER v7 (29, 30) with the x-ray structures (Protein Data Bank entries 2IWV and 2IWW) as templates. The protein was embedded in a preequilibrated, presolvated 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) bilayer (Fig. S7). The simulation set-up protocol was similar to that used in previous studies (31, 32). Ionizable side chains were modeled in their default states at neutral pH based on pKA calculations using PropKA (33). Counterions were added to give an overall neutral system. 0.5 ns of protein-restrained dynamics were followed by a 10-ns unrestrained simulation run.

Simulation Protocols.

Simulations were performed by using GROMACS v3 (34), (www.gromacs.org), with an extended, united atom version of the GROMOS96 force field (35). Long-range electrostatic interactions were calculated by using the particle-mesh Ewald method with a 1-nm cut-off for the real-space calculation (36). A cutoff of 1 nm was used for the van der Waals interactions. The simulation was performed at constant temperature, volume, and number of particles. The temperatures of the protein, detergent, and solvent were each coupled separately. The Nosé–Hoover thermostat was applied at 300 K with the coupling constant τ = 0.5 ps (37). Analyses were performed by using GROMACS routines and locally written scripts. Molecular graphics images were produced by using VMD (10) and PyMOL (38).

Single-Channel Recording of OmpG in Planar Lipid Bilayers.

Planar lipid bilayer experiments were performed in a Delrin cell partitioned with a 25-μm-thick Teflon film. An aperture ≈100 μm in diameter had been made near the center of the film with an electric arc. Each chamber was filled with 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.5)/1 M KCl. A Ag/AgCl electrode was immersed in each chamber with the cis chamber grounded. A positive potential indicates a higher potential in the trans chamber. 1,2-Diphytanoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine (Avanti Polar Lipids) dissolved in pentane (10% vol/vol) was deposited on the surface of the buffer in both chambers, and monolayers formed after the pentane evaporated. The lipid bilayer was formed by raising the liquid level up and down across the aperture, which had been pretreated with a hexadecane/pentane (1:10 vol/vol) solution. OmpG protein (1–5 μl of ≈0.5 mg/ml) was added to the cis chamber, and a potential of +150 mV was applied to induce protein insertion into the lipid bilayer. After a single channel had inserted, the ionic current was recorded at +50 mV, unless otherwise stated. The current was amplified with an Axopatch 200B integrating patch clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments). Signals were filtered with a Bessel filter at 2 kHz (unless otherwise stated) and then acquired by a computer (sampling at 50 μs) after digitization with a Digidata 1320A/D board (Axon Instruments). Data were analyzed with Clampex 10.0 software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. Matthew Holden and James Thompson for suggestions about the manuscript and Beatrice Li for technical support. This work was supported by grants from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (through the Oxford Bionanotechnology Interdisciplinary Research Collaboration), the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Medical Research Council, and the National Institutes of Health. H.B. is the holder of a Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Award.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See Commentary on page 6211.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0711561105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bayley H, Cremer PS. Stochastic sensors inspired by biology. Nature. 2001;413:226–230. doi: 10.1038/35093038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhee M, Burns MA. Nanopore sequencing technology: Nanopore preparations. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayley H. Designed membrane channels and pores. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1999;10:94–103. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(99)80017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conlan S, Bayley H. Folding of a monomeric porin, OmpG, in detergent solution. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9453–9465. doi: 10.1021/bi0344228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conlan S, Zhang Y, Cheley S, Bayley H. Biochemical and biophysical characterization of OmpG: A monomeric porin. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11845–11854. doi: 10.1021/bi001065h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subbarao GV, van den Berg B. Crystal structure of the monomeric porin OmpG. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:750–759. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yildiz O, Vinothkumar KR, Goswami P, Kuhlbrandt W. Structure of the monomeric outer-membrane porin OmpG in the open and closed conformation. EMBO J. 2006;25:3702–3713. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang B, Tamm LK. Structure of outer membrane protein G by solution NMR spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16140–16145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705466104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khalid S, Bond PJ, Carpenter T, Sansom MS. OmpA: Gating and dynamics via molecular dynamics simulations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.05.024. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD—Visual Molecular Dynamics. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu LQ, Bayley H. Interaction of the noncovalent molecular adapter, β-cyclodextrin, with the staphylococcal α-hemolysin pore. Biophys J. 2000;79:1967–1975. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76445-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu LQ, et al. Stochastic sensing of organic analytes by a pore-forming protein containing a molecular adapter. Nature. 1999;398:686–690. doi: 10.1038/19491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Astier Y, Braha O, Bayley H. Toward single molecule DNA sequencing: Direct identification of ribonucleoside and deoxyribonucleoside 5′-monophosphates by using an engineered protein nanopore equipped with a molecular adapter. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1705–1710. doi: 10.1021/ja057123+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rekharsky MV, Inoue Y. Complexation thermodynamics of cyclodextrins. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1875–1918. doi: 10.1021/cr970015o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu L-Q, Cheley S, Bayley H. Prolonged residence time of a noncovalent molecular adapter, β-cyclodextrin, within the lumen of mutant α-hemolysin pores. J Gen Physiol. 2001;118:481–494. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.5.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasianowicz JJ, Brandin E, Branton D, Deamer DW. Characterization of individual polynucleotide molecules using a membrane channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13770–13773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deamer DW, Akeson M. Nanopores and nucleic acids: Prospects for ultrarapid sequencing. Trends Biotechnol. 2000;18:147–151. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(00)01426-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bayley H. Sequencing single molecules of DNA. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:628–637. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhee M, Burns MA. Nanopore sequencing technology: Research trends and applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24:580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beckstein O, et al. Ion channel gating: Insights via molecular simulations. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:85–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong H, Szabo G, Tamm LK. Electrostatic couplings in OmpA ion-channel gating suggest a mechanism for pore opening. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:627–635. doi: 10.1038/nchembio827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moroni A, Thiel G. Flip-flopping salt bridges gate an ion channel. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:572–573. doi: 10.1038/nchembio1106-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bond PJ, Faraldo-Gómez JD, Sansom MSP. OmpA—A pore or not a pore? Simulation and modelling studies. Biophys J. 2002;83:763–775. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75207-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu N, Delcour AH. The spontaneous gating activity of OmpC porin is affected by mutations of a putative hydrogen bond network or of a salt bridge between the L3 loop and the barrel. Protein Eng. 1998;11:797–802. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.9.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu N, et al. Effects of pore mutations and permeant ion concentration on the spontaneous gating activity of OmpC porin. Protein Eng. 2000;13:491–500. doi: 10.1093/protein/13.7.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bainbridge G, et al. Voltage-gating of Escherichia coli porin: A cystine-scanning mutagenesis study of loop 3. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:171–176. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eppens EF, et al. Role of the constriction loop in the gating of outer membrane porin PhoE of Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1997;415:317–320. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phale PS, et al. Voltage gating of Escherichia coli porin channels: Role of the constriction loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6741–6745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marti-Renom MA, et al. Comparative protein structure modelling of genes and genomes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:291–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sali A, Blundell TL. Comparative protein modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khalid S, Bond PJ, Deol SS, Sansom MSP. Modelling and simulations of a bacterial outer membrane protein: OprF from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinformatics. 2005;63:6–15. doi: 10.1002/prot.20845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khalid S, Sansom MSP. Molecular dynamics simulations of a bacterial autotransporter: NalP from Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Membr Biol. 2006;23:499–508. doi: 10.1080/09687860600849531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H, Robertson AD, Jensen JH. Very fast empirical prediction and interpretation of protein pKa values. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinformatics. 2005;61:704–721. doi: 10.1002/prot.20660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindahl E, Hess B, van der Spoel D. GROMACS 3.0: A package for molecular simulation and trajectory analysis. J Mol Model. 2001;7:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Gunsteren WF, et al. Biomolecular Simulation: The GROMOS96 Manual and User Guide. Groningen & Zurich: Biomos & Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zurich; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald—An N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nosé S. A molecular dynamics method for simulations in the canonical ensemble. Mol Phys. 1984;52:255–268. [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphic System. San Carlos, CA: Delano Scientific; 2004. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.