Abstract

We previously demonstrated a characteristically high sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells to interferon alpha (IFN-α) gene transfer, which induced a more prominent growth suppression and cell death in pancreatic cancer cells than in other types of cancers and normal cells. The IFN-α protein can exhibit both direct cytotoxicity and indirect immunological antitumour activity. Here, we dissected and examined the two mechanisms, taking advantage of the fact that IFN-α did not show any cross-species activity in its in vivo effect. When a human IFN-α adenovirus was injected into subcutaneous xenografts of human pancreatic cancer cells in nude mice, tumour growth was significantly suppressed due to cell death in an adenoviral dose-dependent manner. The IFN-α protein concentration was markedly increased in the injected subcutaneous tumour, but leakage of the potent cytokine into the systemic blood circulation was minimal. When a mouse IFN-α adenovirus was injected into the same subcutaneous tumour system, all mice showed significant tumour inhibition, an effect that was dependent on the indirect antitumour activities of IFN-α, notably a stimulation of natural killer cells. Moreover, in this case, tumour regression was observed not only for the injected subcutaneous tumours but also for the untreated tumours at distant sites. This study suggested that a local IFN-α gene therapy is a promising therapeutic strategy for pancreatic cancer, due to its dual mechanisms of antitumour activities and lack of significant toxicity.

Keywords: gene transfer, pancreatic cancer, interferon alpha, natural killer cell

Adenocarcinoma of the pancreas is, at present, one of the most intractable cancers, and despite recent advances of therapeutic and diagnostic modalities, the prognosis remains unimproved (Haller, 2003; Safioleas and Moulakakis, 2004). Patients with pancreatic cancer often succumb to local recurrence or metastatic spread (Akerele et al, 2003; Safioleas and Moulakakis, 2004). One major reason for the poor prognosis is that the cancer cells, even when they are small, have a high propensity to infiltrate to the surrounding tissues and metastasise to distant organs. Therefore, it is often necessary to consider pancreatic cancer as a systemic disease, and new therapeutic strategies that effectively target this cancer in vivo, are required (Okusaka and Kosuge, 2004; Yoshida et al, 2004).

The interferon alpha (IFN-α) protein is a cytokine with multiple biological activities that include antiviral activity, regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation and immunomodulation (Pfeffer et al, 1998). The cytokine has been used worldwide for the treatment of a variety of cancers including some haematological malignancies (hairy cell leukaemia, chronic myeloid leukaemia, some B- and T-cell lymphoma) and certain solid tumours such as melanoma, renal carcinoma and Kaposi's sarcoma (Gutterman, 1994; Pfeffer et al, 1998). However, clinical experiences with IFN protein therapy of other cancers, especially in the treatment of many solid tumours, have generally not been encouraging (Pfeffer et al, 1998). In the conventional regimen of IFN clinical trials, the recombinant IFN-α protein is systemically administrated through subcutaneous, intravenous or intramuscular routes. However, pharmacokinetic studies have indicated that the half-life of the IFN-α protein is 3 h in the blood circulation and only 0.01% of subcutaneously injected IFN-α can reach the target sites (Salmon et al, 1996; Suzuki et al, 2003), indicating that IFN-α protein delivery might be insufficient and/or at an unsustainable level in the tumour site. This may be the major reason why the previous trials based on the conventional IFN-α therapy failed to show an adequate antitumour effect. By contrast, improved therapeutic effect and safety are expected for IFN-α gene transfer, because it allows an increased and sustained local concentration of this cytokine in the target sites while minimising unnecessary systemic distribution (Suzuki et al, 2003; Hatanaka et al, 2004). In fact, it has been reported that direct IFN-α gene transfer into tumours suppressed growth of various cancers such as breast cancer, prostate cancer, renal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma and leukaemia (Zhang et al, 1996; Coleman et al, 1998; Hottiger et al, 1999; Iqbal Ahmed et al, 2001). Although no study of IFN-α gene transfer against pancreatic cancer had been reported, we recently found that the expression of IFN-α effectively induced growth suppression and cell death in pancreatic cancer cells, an effect that appeared to be more prominent than in other types of cancers and normal cells (Hatanaka et al, 2004).

In addition to its direct cytotoxicity, IFNs can also exhibit an indirect antitumour effect through immune stimulations. They induce a major histocompatibility complex class I expression, cause an increase in cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity, enhance the generation of T helper cells and activate macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells (Chawla-Sarkar et al, 2003). In this study, to explore the immunological antitumour activity of IFN-α gene therapy, we tested mouse IFN-α gene delivery into human pancreatic cancer xenograft tumours in nude mice. Although the mouse IFN-α did not show a direct antiproliferative effect against human pancreatic cancer cells in vitro, the mouse IFN-α gene transduction into pancreatic cancer xenografts showed significant inhibition of tumour growth, which was attributed to an IFN-α-induced stimulation of NK cells. This study together with our previous report showing a characteristically high sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells to the direct cytotoxicity of IFN-α transgene expression (Hatanaka et al, 2004) suggests that IFN-α gene therapy is a promising therapeutic strategy for pancreatic cancer, due to its dual mechanisms of antitumour activities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and recombinant adenovirus vectors

Human pancreatic cancer cell lines (Panc-1, AsPC-1, BxPC-3 and MIAPaCa-2) and murine renal cancer cell line (Renca) were used in this study. All cell lines were obtained from American Tissue Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA), and were maintained in an RPMI-1640 medium with 10% foetal bovine serum. The recombinant adenovirus vectors expressing human IFN-α2a (AxCA-IFN), mouse IFN-α (AdCA-mIFN), enhanced green fluorescein protein (AdCA-EGFP) and alkaline phosphatase cDNA (AdCA-AP) were prepared as described (Aoki et al, 1999; Nakano et al, 2001; Suzuki et al, 2003). A cesium chloride-purified virus was desalted using a sterile Bio-Gel P-6 DG chromatography column (Econopac DG 10, BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) and diluted for storage in a 13% glycerol/PBS solution. All viral preparations were confirmed to be free of E1+ adenovirus by PCR assay (Zhang et al, 1995).

In vitro growth analysis

The AsPC-1 and Renca cells were seeded at 2 × 103 well−1 in 96-well plates and infected with AxCA-IFN, AdCA-mIFN or AdCA-EGFP at an MOI of 10, 30 and 100. The cell numbers were assessed by a colorimetric cell viability assay using a water-soluble tetrazolium salt (Tetracolor One; Seikagaku Corp., Tokyo, Japan) 5 days after the infection. The absorbance was determined by spectrophotometry using a wavelength of 450 nm with 595 nm as a reference. The assays (carried out in eight wells) were repeated a minimum of two times and the mean±standard deviation (s.d.) was plotted. The data were expressed as the relative cell number (OD450 of AxCA-IFN- or AdCA-mIFN-infected cells/OD450 of AdCA-EGFP-infected cells).

Animal model

Female, 7- to 8-week-old BALB/c nude mice were obtained from Charles River Japan (Kanagawa, Japan), and kept in a specific pathogen-free environment. Among the cell lines used in this study, we chose AsPC-1 for an in vivo gene transfer model, because the cells rapidly form a tumour when inoculated in the subcutaneous or peritoneal space of nude mice. For the direct intratumoral treatment of subcutaneous tumours, AsPC-1 cell suspensions (50 μl of 5 × 106 cells) were injected subcutaneously into the left leg. When the tumour mass was established (∼0.5 cm in diameter), 50 μl of a viral solution was injected into the tumour with a 29-G hypodermic needle, and the animals were observed for tumour growth. The short (r) and long (l) diameters of the tumours were measured and the tumour volume of each was calculated as r2l/2. Tumour sizes (mean±s.e.m. (standard error of mean)) were measured on the days indicated. For the distant metastasis treatment, 5 × 106 of AsPC-1 cells were injected subcutaneously into the left leg and 1 × 106 of AsPC-1 cells were simultaneously injected into the right leg. When the tumour mass on the left leg was established (∼0.5 cm in diameter), 50 μl (1.0 × 108 PFU) of the viral solution was injected once into the subcutaneous tumour on the left leg, and the animals were observed for tumour growth on both legs. For the peritoneal dissemination treatment, 5 × 106 cells of AsPC-1 cell suspensions were injected subcutaneously into the left leg. When the tumour mass on the left leg was established, 1 × 106 or 5 × 106 cells of AsPC-1 cell suspensions were injected into the peritoneal cavity. After 1 day, 1.0 × 108 PFU of the viral solution was injected once into the subcutaneous tumour, and the animals were observed for survival. For NK cell depletion experiments, we started the intraperitoneal injection (50 μl) of anti-asialo GM1 antibody (30 mg ml−1: Wako Chemicals USA Inc., Richmond, VA, USA) 2 days before the vector administration and the treatment was repeated every 2–3 days for five times. Animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Core and Use Committee of the National Cancer Center Research Institute.

RT–PCR and flow cytometric analyses of NKG2D ligands

PCR amplification of five known genes of NKG2D ligands (MICA, MICB, ULBP-1, ULBP-2 and ULBP-3) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was carried out using total RNA from the cells in a 50 μl of PCR mixture containing 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1 U of recombinant Taq DNA polymerase and the following primer set: MICA upstream (5′-TTCCTGCTTCTGGCTGGCATC-3′) and downstream primers (5′-GCAGAAACATGGAATGTCTGCCAA-3′); MICB upstream (5′-CTGCTGTTTCTGGCCGTCGC-3′) and downstream primers (5′-GAAACATATGGAAAGTCTGTCCG-3′); ULBP-1 upstream (5′-CGCCTTCCTTCTGTGCCTCC-3′) and downstream primers (5′-AGATGATGAGAAGGCTCCAGGG-3′); ULBP-2 upstream (5′-AAGATCCTTCTGTGCCTCCCG-3′) and downstream primers (5′-GGATGATGAGGAGGCAGCAAAG-3′); ULBP-3 upstream (5′-GCGATCCTTCCGCGCCTC-3′) and downstream primers (5′-CAGGGTTTCTCGCTGAGGGAC-3′); and GAPDH upstream (5′-TGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGT-3′) and downstream primers (5′-CATGTGGGCCATGAGGTCCACCAC-3′). In total, 35 cycles (GAPDH: 27 cycles) of the PCR were carried out at 94°C for 30 s, 68°C (MICB: 65°C, GAPDH: 60°C) for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel. Daudi (human Burkitt's lymphoma) and K562 (human chronic myelogenous leukaemia) cells were used as negative and positive controls, respectively, for NKG2D ligands. The surface expression of MICA and MICB was then evaluated by flow cytometry. Cells (5 × 105) were incubated at 4°C for 30 min with phycoerythrin-conjugated mouse anti-human MICA/B monoclonal antibody (6D4; IgG, BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA) or isotype control antibody (IgG), and then washed twice with PBS containing 2% BSA and 0.05% NaN3 and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde solution. Flow cytometry was carried out using a FACScan system (Becton Dickinson).

NK cell assay

To determine NK cell activity, BALB/c nude mice were killed 14 days after the administration of the vector. The spleen from each animal was pressed through a nylon mesh and the cells were suspended in DMEM containing 2.5 mM EDTA and 3 U ml−1 of heparin. The suspension was then washed twice with PBS, and incubated with anti-NK cell antibody (DX5)-coated magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA) and passed through a separation column to isolate the NK cells. NK cell activity was determined using a chromium release assay described previously (Tada et al, 2001). Briefly, 1 × 106 YAC-1 mouse lymphoma cells (American Tissue Culture Collection) were radiolabelled with 3.7 Mbq of sodium chromate (51Cr) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA) in 500 μl of RPMI-1640 at 37°C for 2 h. The cells were then washed twice with PBS and diluted to 1 × 104 cells 100 μl−1. Effector cells (NK cells) were added at various effector/target ratios, and a final volume of 100 μl was added to the wells of a U-shaped 96-well plate. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 4 h. The 96-well plate was then centrifuged, and the 51Cr release from 100 μl of supernatant was counted in a liquid scintillation counter. The percentage of cytotoxicity was determined by the formula: (experimental release−spontaneous release/maximum release−spontaneous release) × 100.

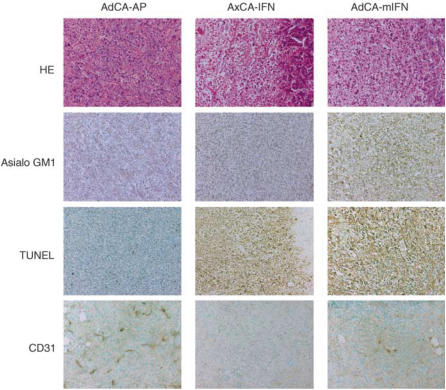

Histology

At 5 days after the injection of 1.0 × 108 PFU of viral solutions (AxCA-IFN, AdCA-mIFN and AdCA-AP), the mice were killed and subcutaneous tumours were collected. The tumours were fixed with formalin, and sections were stained with haematoxylin–eosin or processed for immunohistochemistry with anti-asialo GM1 antibody (Wako Chemicals USA Inc.) and the terminal deoxy-nucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick-end-labelling (TUNEL) assay (ApopTag in situ apoptosis detection kit; Intergen Company, Purchase, NY, USA). For microvessel detection, the fresh tumour samples were embedded in OCT compound (Sakura Finetechnical Co., Tokyo, Japan) and sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then processed for immunohistochemistry with anti-mouse CD31 antibody (MEC13.3; BD Biosciences Pharmingen). Immunostaining was performed using the streptavidin–biotin–peroxidase complex techniques (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan). Parallel negative controls without primary antibodies were run in all cases. The sections were counter-stained with methylgreen. Microvessel areas were quantified by counting of hotspots in sections, and 10 representative fields for each tumour were counted.

Statistical analysis

Comparative analysis of in vivo tumour volume and in vitro cell proliferation was performed by the Student's t-test; mouse survival was analysed by Kaplan–Meier survival plot followed by a log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. Differences were considered statistically significant when P-value was <0.05.

RESULTS

Direct antitumour effect of human IFN-α gene transduction into AsPC-1 tumours

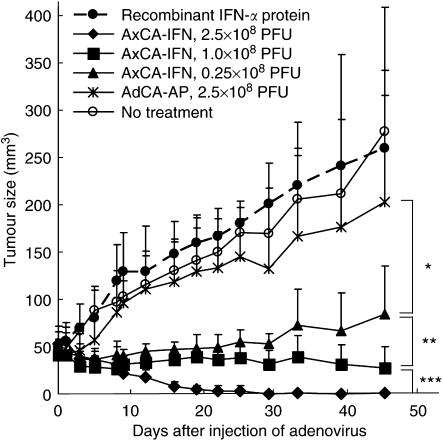

We previously reported that an intratumoral injection of an adenoviral vector expressing the human IFN-α gene, AxCA-IFN (2.5 × 108 PFU), effectively suppressed the growth of nude mouse subcutaneous tumours of the AsPC-1 human pancreatic cancer cells (Hatanaka et al, 2004). In this study, the superior antitumour effect of the IFN-α gene therapy over the recombinant IFN-α protein therapy was evaluated between the single injection of 1.0 × 108 PFU of AxCA-IFN and 3 × 105 IU g−1 of recombinant IFN-α protein, which corresponds to the top level achieved by the 1.0 × 108 PFU of AxCA-IFN infection as shown in Figure 2. The injection of AxCA-IFN showed remarkable tumour suppressive effects in a dose-dependent manner, whereas recombinant IFN-α protein therapy failed to produce a significant therapeutic response (Figure 1), suggesting that an antitumour effect needs a sustained and efficient local expression of IFN-α.

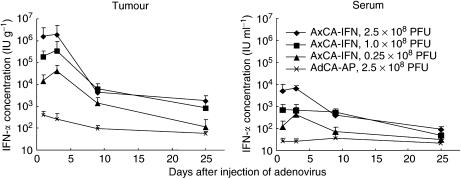

Figure 2.

IFN-α concentration in the subcutaneous tumour and the serum after a single intratumoral injection of AxCA-IFN at various doses. IFN-α was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (Immunotech, Marseille Cedex, France) (n=4).

Figure 1.

Direct antitumour effect of human IFN-α gene transduction into AsPC-1 subcutaneous tumours. When the AsPC-1 subcutaneous tumour was established on the left leg, the tumour was injected once with 2.5, 1.0 or 0.25 × 108 PFU of AxCA-IFN, 2.5 × 108 PFU of AdCA-AP or 3 × 105 IU g−1 of recombinant IFN-α protein (n=6). Tumour size in each mouse was plotted on the days indicated. *P<0.05 for tumours treated with AxCA-IFN at 0.25 × 108 PFU vs treated with AdCA-AP at 2.5 × 108 PFU, **P<0.05 for tumours treated with AxCA-IFN at 0.25 × 108 PFU vs treated at 1.0 × 108 PFU, ***P<0.01 for tumours treated with AxCA-IFN at 1.0 × 108 PFU vs treated at 2.5 × 108 PFU.

High IFN-α expression in subcutaneous tumour tissues following intratumoral injection of AxCA-IFN with little leakage into serum

To determine the kinetics of IFN-α expression after intratumoral injection of AxCA-IFN, the IFN-α levels were measured in the subcutaneous tumour and serum. As shown in Figure 2, the peak levels in the tumour tissue were observed 3 days after the injection and the expression continued for more than 10 days. Although the injection of 2.5 × 108 PFU of AdCA-AP showed a slight expression of IFN-α at day 1, which may be a naïve reaction in response to viral infection, the IFN-α expression returned to the base line (<300 IU g−1) by day 9. The subcutaneous tumour showed approximately 100–1000-fold higher IFN-α levels than the serum did (Figure 2), confirming a markedly increased IFN-α concentration in the subcutaneous tumour with little leakage into the serum (Hatanaka et al, 2004). After the intratumoral injection of recombinant IFN-α protein (3 × 105 IU g−1), the concentration of IFN-α was 609±130 IU g−1 at day 1 and returned to the base line by day 3, which indicated the injected recombinant IFN-α protein was rapidly degraded in the tumour.

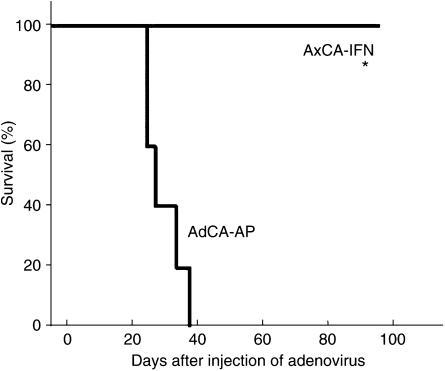

Inhibition of peritoneal dissemination by AxCA-IFN

Peritoneal dissemination is an often fatal end-stage manifestation of pancreatic cancer in the clinical setting. To test the in vivo antitumour effect against peritoneal dissemination, 5 × 106 of AsPC-1 cells were inoculated into the peritoneal cavity of nude mice, and 3 days later, the AxCA-IFN was injected intraperitoneally. Within 42 days after the adenovirus injection, all the control AdCA-AP-injected mice died of peritoneal dissemination that includes tumour formations on the mesentery, pancreas and hepatic hilus. By contrast, the AxCA-IFN-treated group showed a significant suppression of AsPC-1 cell growth in the peritoneal cavity, allowing all the mice to survive more than 100 days (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Treatment of peritoneal dissemination by the intraperitoneal injection of AxCA-IFN. At 3 days after the intraperitoneal injection of AsPC-1 cells (2 × 106 cells), 2.5 × 108 PFU of AxCA-IFN (n=5) or AdCA-AP (n=5) was intraperitoneally injected, and animals were observed for survival. *P<0.01 for survival rates of mice treated with AxCA-IFN vs treated with AdCA-AP.

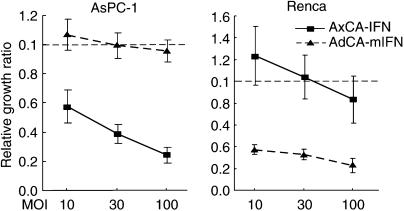

No cross-species activity in the antiproliferative effect of IFN-α

To explore the immunological antitumour effect of IFN-α gene therapy, we transduced the mouse IFN-α gene into human pancreatic cancer xenografts in nude mice. First, the lack of cross-species activity of IFN-α was confirmed by infecting human pancreatic cancer (AsPC-1) and mouse renal cancer (Renca) cells in vitro with a human or mouse IFN-α adenovirus. The infection with AxCA-IFN showed significant growth suppression of AsPC-1 cells but not Renca cells. Conversely, the infection with AdCA-mIFN resulted in marked growth retardation in Renca cells, whereas its growth suppressive effect was not significant in AsPC-1 cells (Figure 4). In our previous report, IFN-α secreted into the medium appeared to account for most, if not all, of the growth suppression (Hatanaka et al, 2004).

Figure 4.

Lack of cross-species activity of human and mouse IFN-α gene transfer. AsPC-1 and Renca cells were infected with AxCA-IFN, AdCA-mIFN or AdCA-EGFP at an MOI of 10, 30 and 100. Cell growth was determined by cell proliferation assay 5 days after the infection.

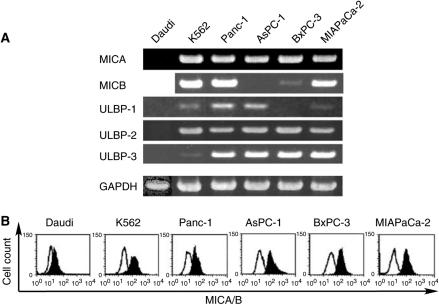

Expression of NKG2D ligands in human pancreatic cancer cells

NK cells are an important element of the innate immune system as they are capable of killing tumour cells. The cytotoxic activity of NK cells is enhanced by IFN-α/β through TRAIL (tumour necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) gene induction (Sato et al, 2001). NKG2D is one of the activating receptors on NK cells, and a number of NKG2D ligands, such as MICA and MICB (major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related) and ULBP (UL16-binding proteins), have been identified (Groh et al, 1999; Bahram, 2000; Kubin et al, 2001; Stephens, 2001; Raulet, 2003; Yokoyama and Plougastel, 2003). It is known that the expression of NKG2D ligands is upregulated in transformed cells, and that the human NKG2D ligands can bind to mouse NKG2D, leading to the activation of mouse NK cells (Kubin et al, 2001). To examine whether the pancreatic cancer cells express the ligands, RT–PCR and flow cytometric analyses were performed in four cell lines (Panc-1, AsPC-1, BxPC-3 and MIAPaCa-2). As shown in Figure 5, all the pancreatic cancer cells examined expressed several kinds of NKG2D ligands, suggesting that the cancer cells are effective targets of NK cells.

Figure 5.

Expression of NKG2D ligands on pancreatic cancer cell lines. (A) RT–PCR analyses of NKG2D ligands. Total RNA was extracted from cell lines and after reverse transcription the mRNA of MICA, MICB, ULBP-1, ULBP-2 and ULBP-3 was detected by PCR. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of MICA and MICB. Cells were incubated with anti-human MICA/B monoclonal antibody (filled curve) or isotype control antibody (open curve), and flow cytometry was carried out using a FACScan system.

Immunological antitumour effect of mouse IFN-α gene transduction into AsPC-1 tumours

We next examined whether mouse IFN-α gene therapy leads to regression of the human AsPC-1 xenograft tumours in nude mice. We injected subcutaneous AsPC-1 tumours with AdCA-mIFN, AxCA-IFN or AdCA-AP at a dose of 1.0 × 108 PFU. Although AxCA-IFN effectively suppressed tumour growth as shown in our previous study (Hatanaka et al, 2004) and Figure 1, complete tumour regression was observed in only one of six mice, and in the particular experiment described here, one of the six mice failed to respond to AxCA-IFN (Figure 6A, middle panel). AdCA-mIFN caused complete regression in four of the six mice, and the remaining two showed a significant growth retardation (Figure 6A, left panel). There was no pathological change in major organs such as the brain, lung, heart, liver, spleen, pancreas, kidney, stomach, intestine, ovary and skeletal muscle of the vector-infected mice (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Immunological antitumour effect of mouse IFN-α gene transduction into AsPC-1 subcutaneous tumours in nude mice. (A) Growth inhibition of subcutaneous tumour injected with AxCA-IFN and AdCA-mIFN. When the AsPC-1 subcutaneous tumour was established on the left leg, 1.0 × 108 PFU of viral solution was injected once into the tumour. Tumour size in each mouse (AdCA-mIFN: n=6; AxCA-IFN: n=6; AdCA-AP: n=4) was plotted on the days indicated. (B) NK cell activity of AdCA-mIFN-injected mice. NK cells were harvested from the spleens of treated animals 14 days after the intratumoral injection of adenoviruses.

To confirm that mouse IFN-α gene delivery enhanced NK cell activity, we collected splenocytes from the mice that received intratumoral AdCA-mIFN injection and examined the NK cell function. Increased NK cytolysis was observed in these mice compared with the AxCA-IFN- or AxCA-AP-injected mice (Figure 6B). Histological analysis of AdCA-mIFN-injected tumours revealed infiltration of many monocytic cells, which were stained with anti-asialo GM1 antibody, whereas AxCA-IFN-injected mice also showed massive cell death but rare infiltration of monocytic cells (Figure 7). TUNEL assay of AxCA-IFN- or AdCA-mIFN-injected tumours revealed marked apoptosis induction (Figure 7). An immunohistochemical staining with anti-murine CD31 antibody revealed a significantly decreased microvessel density in the IFN-α gene-transduced AsPC-1 subcutaneous tumour models (Figure 7); 10 representative fields under a microscope showed 121, 13 and 44 microvessel counts for the tumours injected with AdCA-AP, AxCA-IFN and AdCA-mIFN, respectively. However, it was not determined whether the loss of vessels was indirectly caused by the marked cell death or directly caused by the antiangiogenetic activity of IFN-α.

Figure 7.

Histological and immunohistochemical analyses of AsPC-1 tumours treated with AxCA-IFN and AdCA-mIFN. At 5 days after the injection of 1.0 × 108 PFU of viral solutions, the subcutaneous tumours were fixed with formalin for haematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining, immunohistochemistry with anti-asialo GM1 antibody or TUNEL staining (× 200). Fresh tumour samples were embedded in OCT compound and sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then processed for immunohistochemistry with anti-mouse CD31 antibody (× 200).

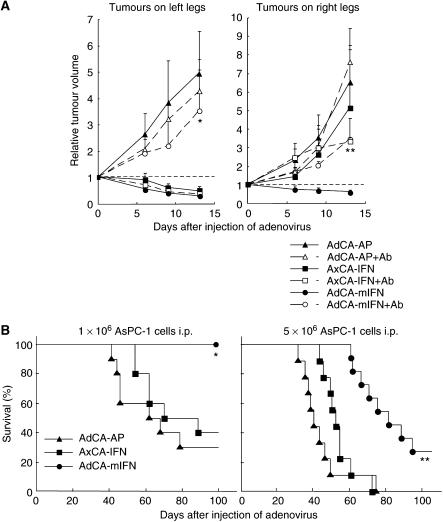

Pretreatment with an anti-asialo GM1 antibody to purge NK cells reduced the antitumour effect of AdCA-mIFN (Figure 8A, left panel) significantly, suggesting that mouse IFN-α expression induced the activation of NK cells, which play a major role in the antitumour effect of AdCA-mIFN.

Figure 8.

Suppression of tumours at distant sites by the intratumoral injection of AdCA-mIFN into subcutaneous xenografts. (A) Suppression of contralateral subcutaneous tumours. The AsPC-1 cells were injected subcutaneously into both legs, and then 1.0 × 108 PFU of viral solution was injected once into the left tumour (n=6). The data (mean±s.d.) were expressed as the relative tumour volume, which is the tumour volume on the days indicated, divided by that on day 0. For NK cell depletion experiments, mice were treated with intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of anti-asialo GM1 antibody for four times. *P<0.05 for tumours on the left legs injected with AdCA-mIFN in the presence or absence of anti-asialo GM1 antibody, **P<0.05 for tumours on the right legs untreated with AdCA-mIFN in the presence or absence of anti-asialo GM1antibody. (B) Suppression of peritoneal dissemination. When the AsPC-1 subcutaneous tumour was established on the left leg, 1 × 106 (left panel) or 5 × 106 cells (right panel) of AsPC-1 cell suspensions were injected into the peritoneal cavity, and 1 day later, 1.0 × 108 PFU of viral solution was injected once into the subcutaneous tumour. (Left panel) AdCA-mIFN: n=10; AxCA-IFN: n=10; AdCA-AP: n=10. (Right panel) AdCA-mIFN: n=11; AxCA-IFN: n=9; AdCA-AP: n=9. ***P<0.01 for survival rate of AdCA-mIFN-treated mice vs AxCA-IFN- and AdCA-AP-treated mice.

No significant systemic toxicity after intratumoral injection of AdCA-mIFN

To characterise the potential toxicity of local IFN-α gene therapy, different doses of AdCA-mIFN were injected into the AsPC-1 subcutaneous tumours, and the animals were killed 5 or 11 days later to evaluate serum enzyme values and histology of major organs. All treated mice looked healthy during the course of the experiment. Although a mild elevation of the hepatic enzymes (AST and ALT) was observed at day 5 only when a relatively high dose (2.5 × 108 PFU) of IFN-α adenovirus was injected into the tumours (Table 1), their values returned to a normal range at day 11. Other biochemical markers (albumin, alkaline phosphatase, BUN, creatinin) were within normal limits, and there were no pathological changes in major organs in all of the treated animals, suggesting that systemic toxicity of local IFN-α gene therapy is minimal.

Table 1. Evaluation of selected serum chemistries 5 days after intratumoral injection of AdCA-mIFN.

|

AdCA-mIFN

|

AdCA-AP

|

No treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (PFU): × 108 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 0.25 | 2.5 | — |

| Mouse IFN concentration | |||||

| Tumour (pg g−1): × 103 | 252.3±292.2 | 53.0±30.0 | 14.3±13.4 | 1.4±0.6 | 0.8±0.2 |

| Serum (pg ml−1): × 103 | 1.7±0.9 | 0.3±0.1 | 0.3±0.2 | 0.2±0.1 | 0.2±0.1 |

| Albumin (g dl−1) | 2.8±0.3 | 2.9±0.4 | 2.8±0.4 | 2.7±0.1 | 2.9±0.3 |

| Alk. phos. (IU l−1) | 231±71 | 186±29 | 199±44 | 186±21 | 218±81 |

| Amylase (U l−1) | 13 910±3932 | 16 595±6937 | 17 790±453 | 14 850±353 | 10 269±3922 |

| BUN (mg dl−1) | 19.1±1.6 | 23.6±6.4 | 21.2±2.4 | 22.7±1.3 | 23.9±4.0 |

| Creatinine (mg dl−1) | 0.08± 0.02 | 0.09± 0.02 | 0.1±0.01 | 0.09±0.02 | 0.11±0.03 |

| LDH (IU l−1) | 379± 69 | 316±68 | 560±244 | 486±252 | 368±216 |

| AST (IU l−1) | 126±4 | 101±42 | 93±34 | 68±17 | 70±23 |

| ALT (IU l−1) | 54±32 | 28±4 | 25±7 | 18±10 | 19±5 |

| T. bil. (mg dl−1) | 0.05±0.01 | 0.04±0.01 | 0.05±0.01 | 0.06±0.01 | 0.04±0.01 |

Suppression of tumours at distant sites by intratumoral injection of AdCA-mIFN

We then tested whether mouse IFN-α gene transduction has an effect on untreated tumours at distant sites. We injected AsPC-1 cells into both legs, and when the tumour diameter reached about 5 mm, 1 × 108 PFU of AdCA-mIFN was injected once into the tumour on the left leg. A regression of both the treated tumour on the left leg and the untreated tumour on the opposite leg was observed, whereas the injection of the control AdCA-AP or AxCA-IFN did not affect the growth of tumours on the right leg. When we pretreated the mice with an anti-asialo GM1 antibody to purge NK cells, the mouse IFN-α-induced antitumour effect was cancelled (Figure 8A, right panel).

As another model of distant metastasis, we injected AsPC-1 cells into the left leg and the peritoneal cavity, and again, when tumour mass was established on the left leg, 1 × 108 PFU of adenovirus was injected once into the tumour. The treatment with AdCA-mIFN resulted in a profound and statistically significant improvement (P<0.01) in the survival of the treated mice as compared with AxCA-IFN and AdCA-AP (Figure 8B). All of the dead animals were confirmed to have disseminated tumours in the peritoneal cavity. These data demonstrated that the antitumour effect of a local IFN-α gene therapy is not limited to a locally injected tumour site, but that it can induce a systemic immunity against pancreatic cancer cells.

DISCUSSION

It has been reported that the modes of antitumour responses from IFN-α gene therapy manifested three aspects: direct antiproliferative effect (Zhang et al, 1996; Ahmed et al, 1999, 2001; Iqbal Ahmed et al, 2001; Demers et al, 2002), stimulation of cytotoxic T cells (Coleman et al, 1998; Horton et al, 1999; Li et al, 2001) and antiangiogenesis activity (Indraccolo et al, 2002a, 2002b). Although others highlighted each antitumour mechanism in the basic studies of IFN-α gene therapy, in this study we demonstrated that intratumoral injection of the IFN-α adenovirus could effectively suppress xenograft tumours of pancreatic cancer due to the dual mechanisms of antitumour activities: the direct regional apoptosis induction and the systemic immunological effect at least through NK cell activation. Furthermore, the IFN-α protein concentration was markedly increased in the injected subcutaneous tumour, but leakage into the serum was minimal, suggesting the safety of intratumoral injection of an IFN-α adenovirus. Qin et al (2001) also reported that IFN-β gene therapy induced direct antitumour activity and an immunological effect of NK cells against human glioblastoma. However, IFN-β protein showed less of an antiproliferative effect against pancreatic cancer cells than did IFN-α (unpublished data). Although the type 1 IFNs, the α-family and β, share receptor components, they were observed to have differences in their receptor binding and signalling (Abramovich et al, 1994a, 1994b), which may explain their different antitumour activities.

In this study, we injected the IFN-α-expressing vector locally to the tumour mass. In pancreatic cancer, such a regional therapy is particularly relevant, because locally advanced cases are surgically unresectable but can be accessible by laparoscopy-mediated injection or ultrasound- or CT-guided percutaneous injection. In a clinical setting, IFN-α gene therapy could exert tumour suppressive effects based both on direct cytotoxicity and indirect immunological antitumour activities, the combination of which is expected to be highly efficacious against locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Even though some pancreatic cancer cells are resistant to the direct antiproliferation and cell death-inducing activities of IFN-α, such resistant cancer cells could be suppressed by the activation of the innate immune system, as shown in this study. The NK cells can be activated locally in the tumour and/or activated systemically through immune organs such as the spleen (Qin et al, 2001). The latter can result from vector dissemination into the spleen or the circulation of a low level of IFN-α that is released by the vector-transduced tumour cells. Pancreatic cancer cells might be an effective target of activated NK cells, because the cancer cell lines express a variety of NKG2D ligands as shown in Figure 5. Moreover, cytokine-mediated activation of a host adaptive immune system may also contribute to the mounting of a systemic immunity against pancreatic cancer in this direct local IFN-α gene therapy, although this effect could not be evaluated in our nude mice study. In addition to locally advanced cases, distant metastasis at the liver and in the peritoneal cavity may be a clinical target of local IFN-α gene therapy.

With respect to the safety of the therapy, it is noteworthy that the IFN-α gene transfer showed very limited antiproliferative effects on normal cells such as hepatocytes and vascular endothelial cells (Hatanaka et al, 2004), although their mechanisms are still not fully understood. In addition, there was much difference in the IFN-α protein concentration between a vector-injected tumour tissue and the serum. In fact, although a mild elevation of hepatic enzymes was observed at day 5 only when a relatively high dose (2.5 × 108 PFU) of IFN-α adenovirus was injected into the tumours (Table 1), the elevation returned to a normal range at day 11. Therefore, we expect that the toxicity of local IFN-α gene therapy is tolerable in human clinical trials, although more preclinical toxicity study using larger animals such as non-human primates will be required. One additional potential advantage of gene therapy technology is that we can design and preinstall safety devices to control transgene effects, such as suicidal gene, regulatable promoter or a Cre/loxP-mediated shut-off system of IFN-α expression in vivo (Suzuki et al, 2003). In sum, our preclinical study suggests that the regional adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of IFN-α is one of the promising new approaches to the pancreatic cancer. The strategy may deserve an evaluation in a future clinical trial for this highly intractable cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Jun-ichi Miyazaki for providing vector pCAGGS. This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for the 2nd and 3rd Term Comprehensive 10-Year Strategy for Cancer Control from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, by grants-in-aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. M Ohashi and Y Miura are awardees of a Research Resident Fellowship from the Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research.

References

- Abramovich C, Chebath J, Revel M (1994a) The human interferon alpha-receptor protein confers differential responses to human interferon-beta vs interferon-alpha subtypes in mouse and hamster cell transfectants. Cytokine 6: 414–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramovich C, Shulman LM, Ratovitski E, Harroch S, Tovey M, Eid P, Revel M (1994b) Differential tyrosine phosphorylation of the IFNAR chain of the type I interferon receptor and of an associated surface protein in response to IFN-alpha and IFN-beta. EMBO J 13: 5871–5877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed CM, Sugarman BJ, Johnson DE, Bookstein RE, Saha DP, Nagabhushan TL, Wills KN (1999) In vivo tumor suppression by adenovirus-mediated interferon alpha2b gene delivery. Hum Gene Ther 10: 77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed CM, Wills KN, Sugarman BJ, Johnson DE, Ramachandra M, Nagabhushan TL, Howe JA (2001) Selective expression of nonsecreted interferon by an adenoviral vector confers antiproliferative and antiviral properties and causes reduction of tumor growth in nude mice. J Interferon Cytokine Res 21: 399–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerele CE, Rybalova I, Kaufman HL, Mani S (2003) Current approaches to novel therapeutics in pancreatic cancer. Invest New Drugs 21: 113–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki K, Barker C, Danthinne X, Imperiale MJ, Nabel GJ (1999) Efficient generation of recombinant adenoviral vectors by Cre-lox recombination in vitro. Mol Med 5: 224–231 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahram S (2000) MIC genes: from genetics to biology. Adv Immunol 76: 1–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla-Sarkar M, Lindner DJ, Liu YF, Williams BR, Sen GC, Silverman RH, Borden EC (2003) Apoptosis and interferons: role of interferon-stimulated genes as mediators of apoptosis. Apoptosis 8: 237–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M, Muller S, Quezada A, Mendiratta SK, Wang J, Thull NM, Bishop J, Matar M, Mester J, Pericle F (1998) Nonviral interferon alpha gene therapy inhibits growth of established tumors by eliciting a systemic immune response. Hum Gene Ther 9: 2223–2230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demers GW, Johnson DE, Machemer T, Looper LD, Batinica A, Beltran JC, Sugarman BJ, Howe JA (2002) Tumor growth inhibition by interferon-alpha using PEGylated protein or adenovirus gene transfer with constitutive or regulated expression. Mol Ther 6: 50–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh V, Rhinehart R, Secrist H, Bauer S, Grabstein KH, Spies T (1999) Broad tumor-associated expression and recognition by tumor-derived gamma delta T cells of MICA and MICB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 6879–6884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutterman JU (1994) Cytokine therapeutics: lessons from interferon alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 1198–1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller DG (2003) Chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 56: 16–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatanaka K, Suzuki K, Miura Y, Yoshida K, Ohnami S, Kitade Y, Yoshida T, Aoki K (2004) Interferon-alpha and antisense K-ras RNA combination gene therapy against pancreatic cancer. J Gene Med 6: 1139–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton HM, Anderson D, Hernandez P, Barnhart KM, Norman JA, Parker SE (1999) A gene therapy for cancer using intramuscular injection of plasmid DNA encoding interferon alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 1553–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hottiger MO, Dam TN, Nickoloff BJ, Johnson TM, Nabel GJ (1999) Liposome-mediated gene transfer into human basal cell carcinoma. Gene Therapy 6: 1929–1935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indraccolo S, Gola E, Rosato A, Minuzzo S, Habeler W, Tisato V, Roni V, Esposito G, Morini M, Albini A, Noonan DM, Ferrantini M, Amadori A, Chieco-Bianchi L (2002a) Differential effects of angiostatin, endostatin and interferon-alpha1 gene transfer on in vivo growth of human breast cancer cells. Gene Therapy 9: 867–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indraccolo S, Habeler W, Tisato V, Stievano L, Piovan E, Tosello V, Esposito G, Wagner R, Uberla K, Chieco-Bianchi L, Amadori A (2002b) Gene transfer in ovarian cancer cells: a comparison between retroviral and lentiviral vectors. Cancer Res 62: 6099–6107 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal Ahmed CM, Johnson DE, Demers GW, Engler H, Howe JA, Wills KN, Wen SF, Shinoda J, Beltran J, Nodelman M, Machemer T, Maneval DC, Nagabhushan TL, Sugarman BJ (2001) Interferon alpha2b gene delivery using adenoviral vector causes inhibition of tumor growth in xenograft models from a variety of cancers. Cancer Gene Ther 8: 788–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubin M, Cassiano L, Chalupny J, Chin W, Cosman D, Fanslow W, Mullberg J, Rousseau AM, Ulrich D, Armitage R (2001) ULBP1, 2, 3: novel MHC class I-related molecules that bind to human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein UL16, activate NK cells. Eur J Immunol 31: 1428–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Zhang X, Xia X, Zhou L, Breau R, Suen J, Hanna E (2001) Intramuscular electroporation delivery of IFN-alpha gene therapy for inhibition of tumor growth located at a distant site. Gene Therapy 8: 400–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano M, Aoki K, Matsumoto N, Ohnami S, Hatanaka K, Hibi T, Terada M, Yoshida T (2001) Suppression of colorectal cancer growth using an adenovirus vector expressing an antisense K-ras RNA. Mol Ther 3: 491–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okusaka T, Kosuge T (2004) Systemic chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 28: 301–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer LM, Dinarello CA, Herberman RB, Williams BR, Borden EC, Bordens R, Walter MR, Nagabhushan TL, Trotta PP, Pestka S (1998) Biological properties of recombinant alpha-interferons: 40th anniversary of the discovery of interferons. Cancer Res 58: 2489–2499 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin XQ, Beckham C, Brown JL, Lukashev M, Barsoum J (2001) Human and mouse IFN-beta gene therapy exhibits different anti-tumor mechanisms in mouse models. Mol Ther 4: 356–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raulet DH (2003) Roles of the NKG2D immunoreceptor and its ligands. Nat Rev Immunol 3: 781–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safioleas MC, Moulakakis KG (2004) Pancreatic cancer today. Hepatogastroenterology 51: 862–868 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon P, Le Cotonnec JY, Galazka A, Abdul-Ahad A, Darragh A (1996) Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of recombinant human interferon-beta in healthy male volunteers. J Interferon Cytokine Res 16: 759–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Hida S, Takayanagi H, Yokochi T, Kayagaki N, Takeda K, Yagita H, Okumura K, Tanaka N, Taniguchi T, Ogasawara K (2001) Antiviral response by natural killer cells through TRAIL gene induction by IFN-alpha/beta. Eur J Immunol 31: 3138–3146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens HA (2001) MICA and MICB genes: can the enigma of their polymorphism be resolved? Trends Immunol 22: 378–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Aoki K, Ohnami S, Yoshida K, Kazui T, Kato N, Inoue K, Kohara M, Yoshida T (2003) Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of interferon alpha improves dimethylnitrosamine-induced liver cirrhosis in rat model. Gene Therapy 10: 765–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada H, Maron DJ, Choi EA, Barsoum J, Lei H, Xie Q, Liu W, Ellis L, Moscioni AD, Tazelaar J, Fawell S, Qin X, Propert KJ, Davis A, Fraker DL, Wilson JM, Spitz FR (2001) Systemic IFN-beta gene therapy results in long-term survival in mice with established colorectal liver metastases. J Clin Invest 108: 83–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama WM, Plougastel BF (2003) Immune functions encoded by the natural killer gene complex. Nat Rev Immunol 3: 304–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Ohnami S, Aoki K (2004) Development of gene therapy to target pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci 95: 283–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JF, Hu C, Geng Y, Selm J, Klein SB, Orazi A, Taylor MW (1996) Treatment of a human breast cancer xenograft with an adenovirus vector containing an interferon gene results in rapid regression due to viral oncolysis and gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 4513–4518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W-W, Koch PE, Roth JA (1995) Detection of wild-type contamination in a recombinant adenoviral preparation by PCR. BioTechniques 18: 444–447 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]