Abstract

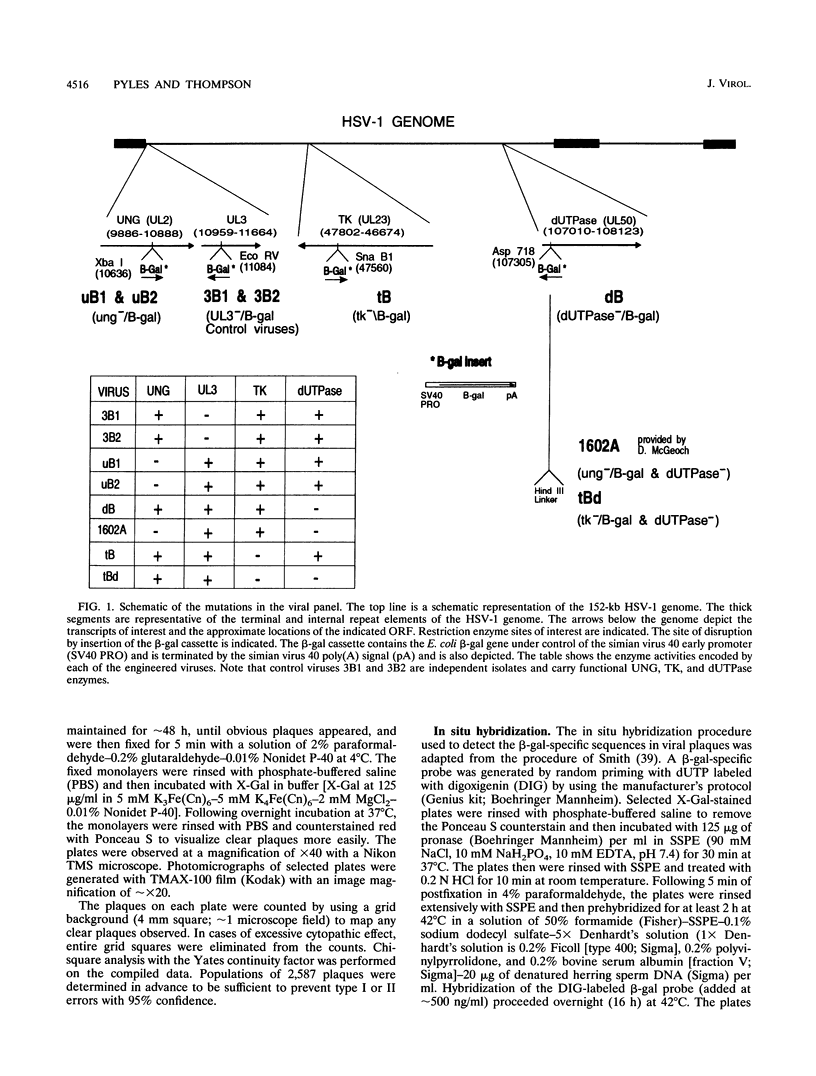

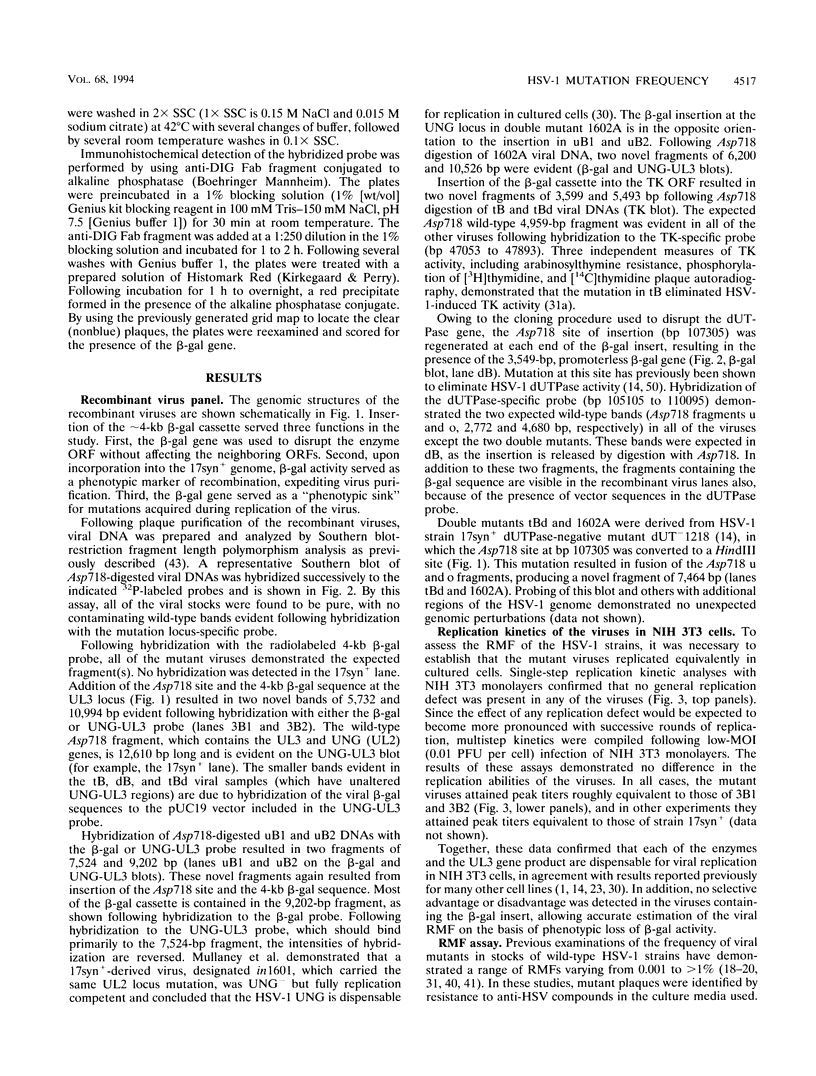

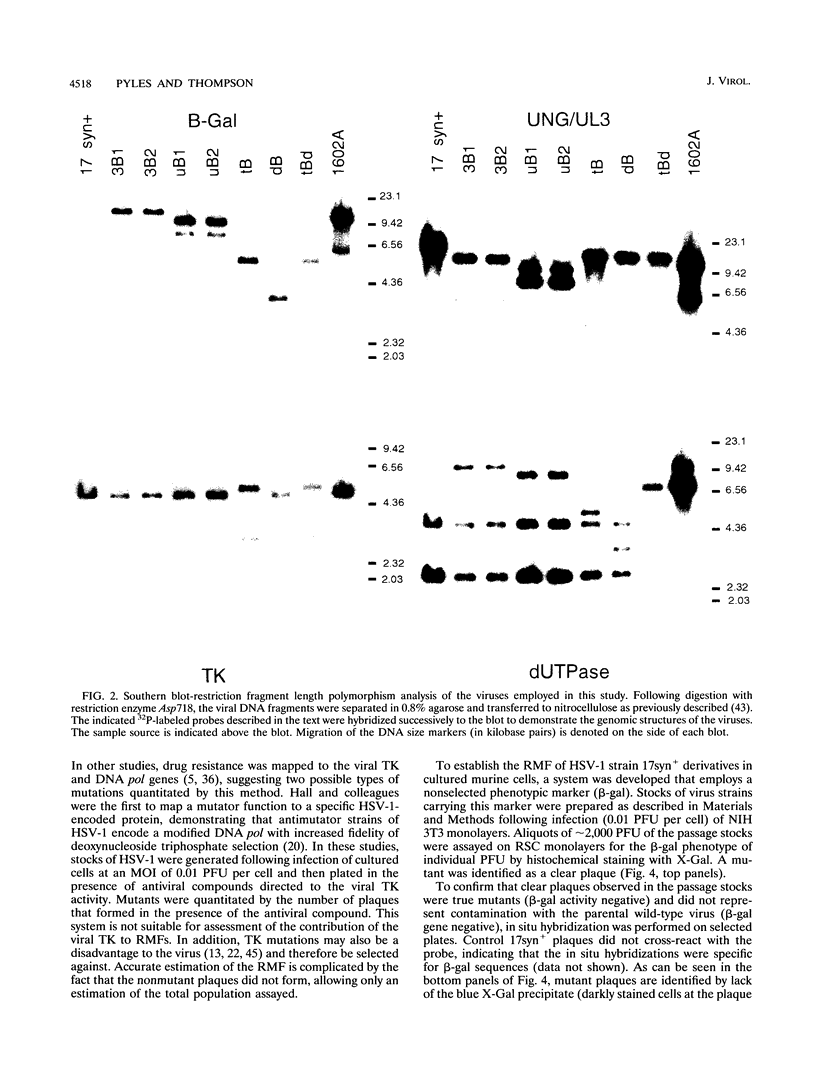

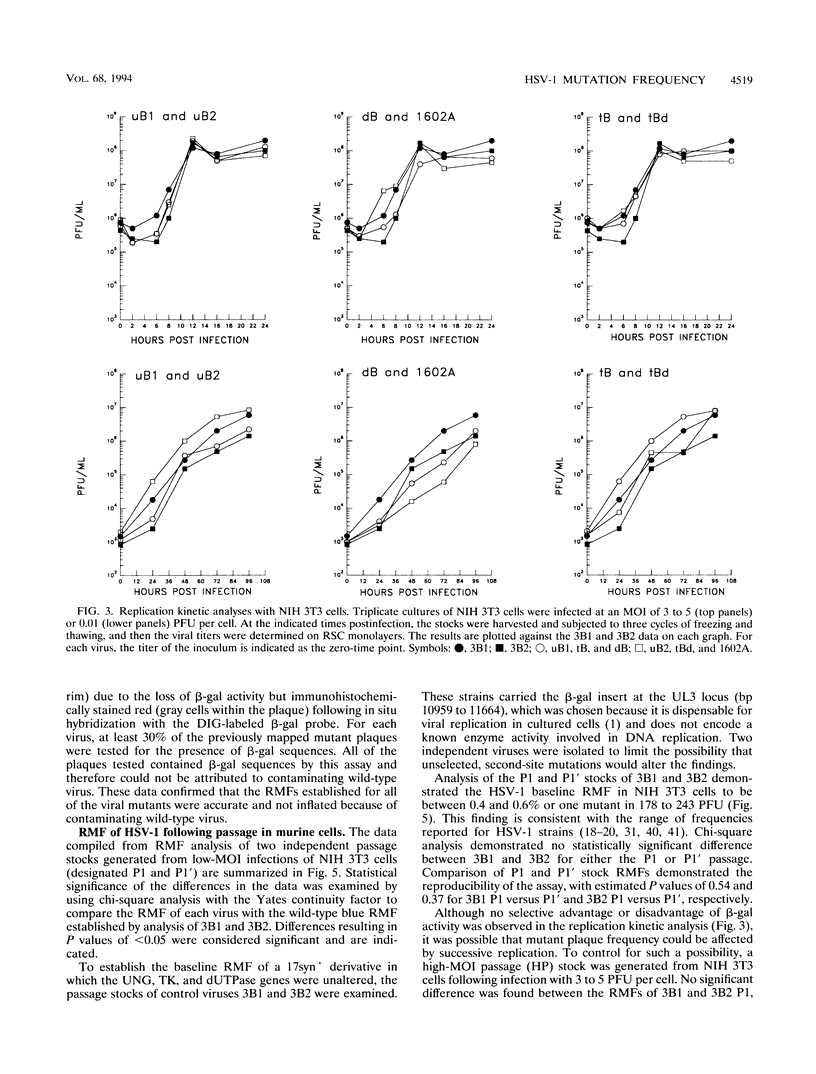

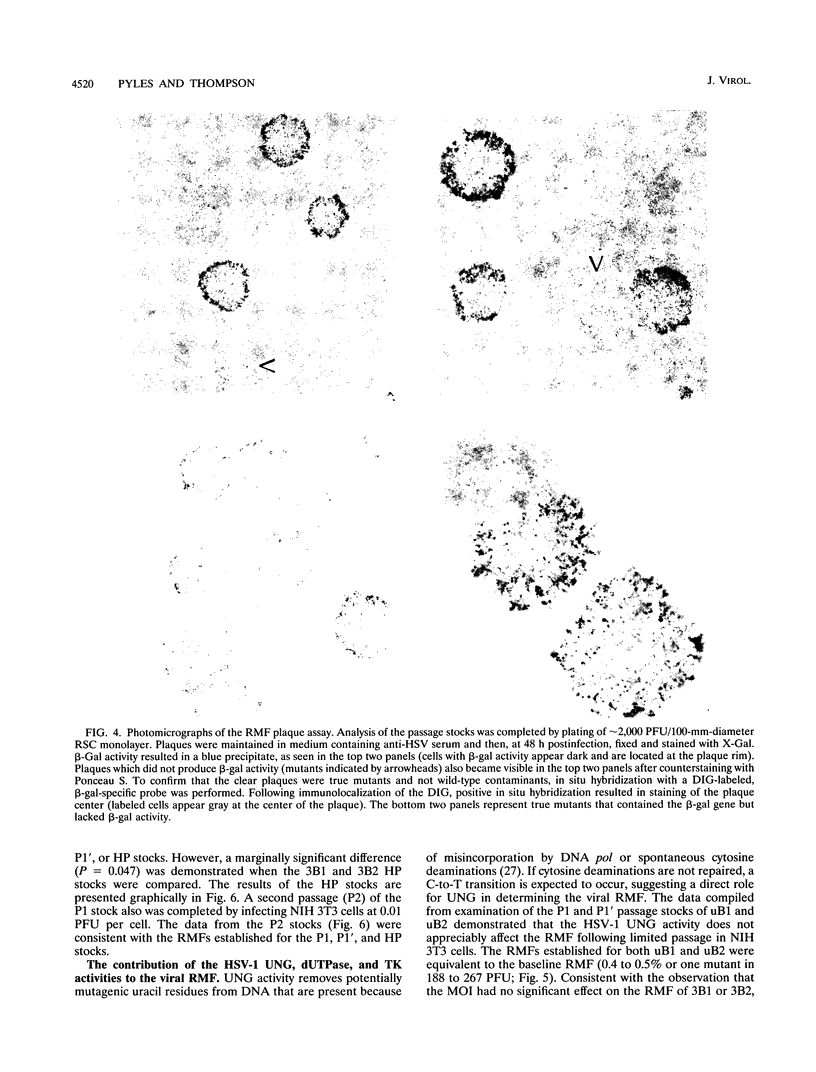

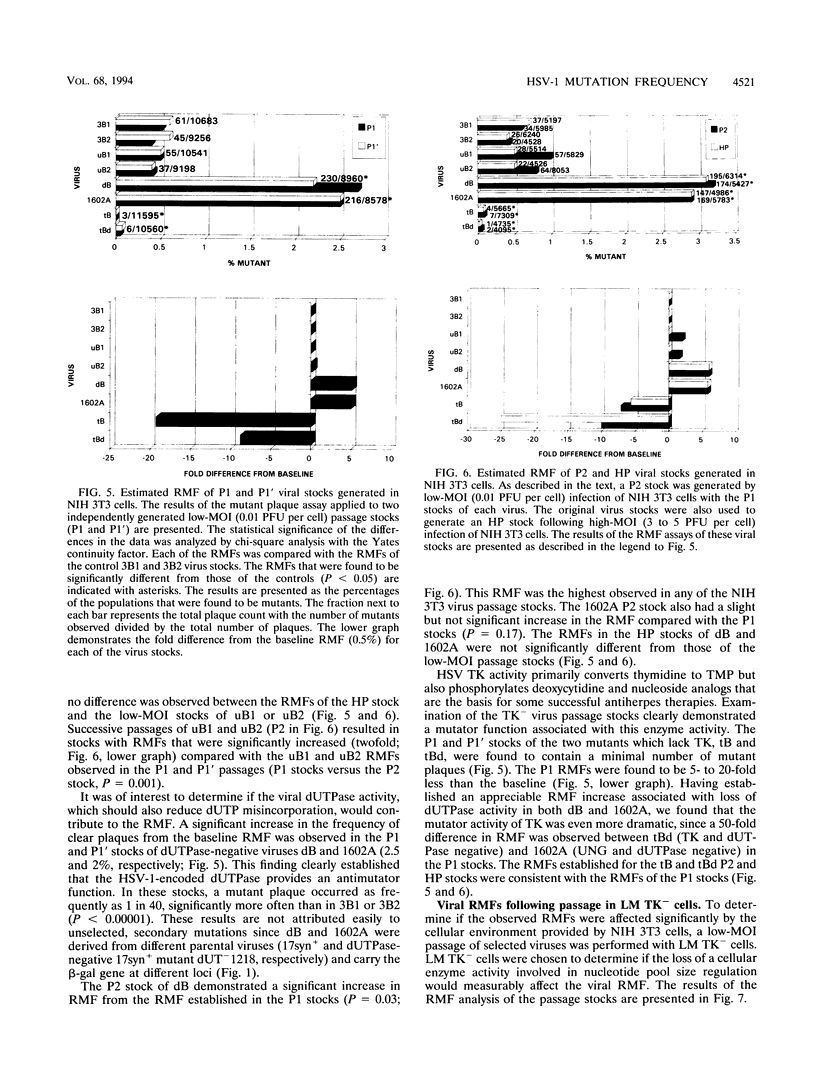

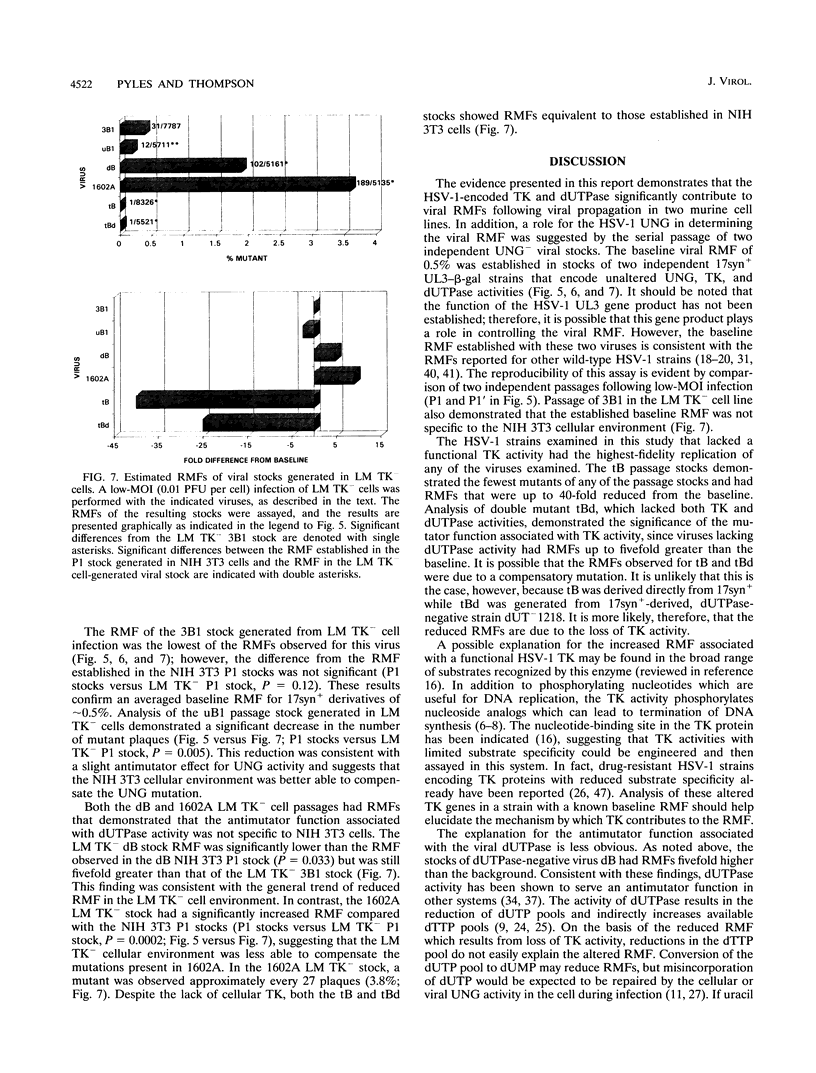

The contribution of the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1)-encoded uracil DNA glycosylase (UNG), thymidine kinase (TK), and dUTPase to the relative mutant frequency (RMF) of the virus in cultured murine cells was examined. A panel of HSV-1 mutants that lacked singly or doubly the UNG, TK, or dUTPase activity were generated by disruption of the enzyme coding regions with the Escherichia coli beta-galactosidase (beta-gal) gene in strain 17syn+. To establish a baseline RMF of strain 17syn+, the beta-gal gene was inserted into the UL3 locus. In all of the viruses, the beta-gal insert served as a phenotypic marker of RMF. A mutant plaque was identified by the lack of beta-gal activity and, in selected cases, positive in situ hybridization for beta-gal sequences. Replication kinetics in NIH 3T3 cells demonstrated that all of the mutants replicated efficiently, generating stocks with equivalent titers. Two independently generated UL3-beta-gal viruses were examined and established a baseline RMF of approximately 0.5% in both NIH 3T3 and LM TK- cells. Loss of dUTPase activity resulted in viruses with fivefold-increased RMFs, indicating that the HSV-1 dUTPase has an antimutator function. The RMF observed for the tk- viruses was reduced as much as 40-fold (RMF of 0.02%), suggesting that the viral TK is a mutator activity. The RMF of two independent UNG- viruses showed no significant difference from the baseline RMF in limited passage; however, following successive passage, the data suggested that UNG activity serves as an antimutator. These results have implications for the natural history of HSV and the development of antiviral therapies.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baines J. D., Roizman B. The open reading frames UL3, UL4, UL10, and UL16 are dispensable for the replication of herpes simplex virus 1 in cell culture. J Virol. 1991 Feb;65(2):938–944. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.2.938-944.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein C., Bernstein H., Mufti S., Strom B. Stimulation of mutation in phage T 4 by lesions in gene 32 and by thymidine imbalance. Mutat Res. 1972 Oct;16(2):113–119. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(72)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns W. H., Saral R., Santos G. W., Laskin O. L., Lietman P. S., McLaren C., Barry D. W. Isolation and characterisation of resistant Herpes simplex virus after acyclovir therapy. Lancet. 1982 Feb 20;1(8269):421–423. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)91620-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challberg M. D., Kelly T. J. Animal virus DNA replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:671–717. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.003323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen D. M. Antiviral drug resistance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;616:224–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb17843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen D. M., Schaffer P. A. Two distinct loci confer resistance to acycloguanosine in herpes simplex virus type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980 Apr;77(4):2265–2269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.4.2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen D. M. The implications of resistance to antiviral agents for herpesvirus drug targets and drug therapy. Antiviral Res. 1991 May;15(4):287–300. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(91)90010-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumpacker C. S., 2nd Molecular targets of antiviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 1989 Jul 20;321(3):163–172. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907203210306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daikoku T., Yamamoto N., Maeno K., Nishiyama Y. Role of viral ribonucleotide reductase in the increase of dTTP pool size in herpes simplex virus-infected Vero cells. J Gen Virol. 1991 Jun;72(Pt 6):1441–1444. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-6-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake J. W., Allen E. F., Forsberg S. A., Preparata R. M., Greening E. O. Genetic control of mutation rates in bacteriophageT4. Nature. 1969 Mar 22;221(5186):1128–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duker N. J., Grant C. L. Alterations in the levels of deoxyuridine triphosphatase, uracil-DNA glycosylase and AP endonuclease during the cell cycle. Exp Cell Res. 1980 Feb;125(2):493–497. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(80)90145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlich K. S., Mills J., Chatis P., Mertz G. J., Busch D. F., Follansbee S. E., Grant R. M., Crumpacker C. S. Acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus infections in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1989 Feb 2;320(5):293–296. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198902023200506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field H. J., Wildy P. The pathogenicity of thymidine kinase-deficient mutants of herpes simplex virus in mice. J Hyg (Lond) 1978 Oct;81(2):267–277. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400025109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher F. B., Preston V. G. Isolation and characterisation of herpes simplex virus type 1 mutants which fail to induce dUTPase activity. Virology. 1986 Jan 15;148(1):190–197. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90414-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Focher F., Verri A., Verzeletti S., Mazzarello P., Spadari S. Uracil in OriS of herpes simplex 1 alters its specific recognition by origin binding protein (OBP): does virus induced uracil-DNA glycosylase play a key role in viral reactivation and replication? Chromosoma. 1992;102(1 Suppl):S67–S71. doi: 10.1007/BF02451788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry G. A. Viral thymidine kinases and their relatives. Pharmacol Ther. 1992;54(3):319–355. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90006-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. D., Almy R. E. Evidence for control of herpes simplex virus mutagenesis by the viral DNA polymerase. Virology. 1982 Jan 30;116(2):535–543. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. D., Coen D. M., Fisher B. L., Weisslitz M., Randall S., Almy R. E., Gelep P. T., Schaffer P. A. Generation of genetic diversity in herpes simplex virus: an antimutator phenotype maps to the DNA polymerase locus. Virology. 1984 Jan 15;132(1):26–37. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. D., Furman P. A., St Clair M. H., Knopf C. W. Reduced in vivo mutagenesis by mutant herpes simplex DNA polymerase involves improved nucleotide selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Jun;82(11):3889–3893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.11.3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday R. Aspects of DNA repair and nucleotide pool imbalance. Basic Life Sci. 1985;31:453–460. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-2449-2_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson A. T., Gentry G. A., Subak-Sharpe J. H. Induction of both thymidine and deoxycytidine kinase activity by herpes viruses. J Gen Virol. 1974 Sep;24(3):465–480. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-24-3-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIT S., DUBBS D. R. PROPERTIES OF DEOXYTHYMIDINE KINASE PARTIALLY PURIFIED FROM NONINFECTED MOUSE FIBROBLAST CELLS. Virology. 1965 May;26:16–27. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(65)90021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz B. A., Kohalmi S. E. Modulation of mutagenesis by deoxyribonucleotide levels. Annu Rev Genet. 1991;25:339–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larder B. A., Cheng Y. C., Darby G. Characterization of abnormal thymidine kinases induced by drug-resistant strains of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1983 Mar;64(Pt 3):523–532. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-3-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl T. DNA glycosylases, endonucleases for apurinic/apyrimidinic sites, and base excision-repair. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1979;22:135–192. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60800-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo K. Y., Bessman M. J. An antimutator deoxyribonucleic acid polymerase. II. In vitro and in vivo studies of its temperature sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 1976 Apr 25;251(8):2480–2486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeoch D. J., Dalrymple M. A., Davison A. J., Dolan A., Frame M. C., McNab D., Perry L. J., Scott J. E., Taylor P. The complete DNA sequence of the long unique region in the genome of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1988 Jul;69(Pt 7):1531–1574. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-7-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullaney J., Moss H. W., McGeoch D. J. Gene UL2 of herpes simplex virus type 1 encodes a uracil-DNA glycosylase. J Gen Virol. 1989 Feb;70(Pt 2):449–454. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-2-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parris D. S., Harrington J. E. Herpes simplex virus variants restraint to high concentrations of acyclovir exist in clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982 Jul;22(1):71–77. doi: 10.1128/aac.22.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyles R. B., Sawtell N. M., Thompson R. L. Herpes simplex virus type 1 dUTPase mutants are attenuated for neurovirulence, neuroinvasiveness, and reactivation from latency. J Virol. 1992 Nov;66(11):6706–6713. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6706-6713.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards R. G., Brown O. E., Sedwick W. D. Misincorporation of deoxyuridine in human cells: consequences of antifolate exposure. Basic Life Sci. 1985;31:149–162. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-2449-2_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH K. O. SOME BIOLOGIC ASPECTS OF HERPESVIRUS-CELL INTERACTIONS IN THE PRESENCE OF 5-IODO, 2-DESOXYURIDINE (IDU). DEMONSTRATION OF A CYTOTOXIC EFFECT BY HERPESVIRUS. J Immunol. 1963 Nov;91:582–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnipper L. E., Crumpacker C. S. Resistance of herpes simplex virus to acycloguanosine: role of viral thymidine kinase and DNA polymerase loci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980 Apr;77(4):2270–2273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.4.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedwick W. D., Brown O. E., Glickman B. W. Deoxyuridine misincorporation causes site-specific mutational lesions in the lacI gene of Escherichia coli. Mutat Res. 1986 Aug;162(1):7–20. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(86)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibrack C. D., McLaren C., Barry D. W. Disease and latency characteristics of clinical herpes virus isolated after acyclovir therapy. Am J Med. 1982 Jul 20;73(1A):372–375. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. H. In situ detection of transcription in transfected cells using biotin-labeled molecular probes. Methods Enzymol. 1987;151:530–539. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(87)51042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. O., Kennell W. L., Poirier R. H., Lynd F. T. In vitro and in vivo resistance of herpes simplex virus to 9-(2-hydroxyethoxymethyl)guanine (acycloguanosine). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980 Feb;17(2):144–150. doi: 10.1128/aac.17.2.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonkin P. L., Baratz K. H., Frothingham R., Cobo L. M. Acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus keratouveitis after penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 1992 Dec;99(12):1805–1808. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31732-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern E. M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975 Nov 5;98(3):503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speyer J. F. Mutagenic DNA polymerase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1965 Oct 8;21(1):6–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(65)90417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenser R. B. Role of herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase expression in viral pathogenesis and latency. Intervirology. 1991;32(2):76–92. doi: 10.1159/000150188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. L., Wagner E. K., Stevens J. G. Physical location of a herpes simplex virus type-1 gene function(s) specifically associated with a 10 million-fold increase in HSV neurovirulence. Virology. 1983 Nov;131(1):180–192. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90544-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veerisetty V., Gentry G. A. Alterations in substrate specificity and physicochemical properties of deoxythymidine kinase of a drug-resistant herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant. J Virol. 1983 Jun;46(3):901–908. doi: 10.1128/jvi.46.3.901-908.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verri A., Mazzarello P., Biamonti G., Spadari S., Focher F. The specific binding of nuclear protein(s) to the cAMP responsive element (CRE) sequence (TGACGTCA) is reduced by the misincorporation of U and increased by the deamination of C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990 Oct 11;18(19):5775–5780. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.19.5775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verri A., Mazzarello P., Spadari S., Focher F. Uracil-DNA glycosylases preferentially excise mispaired uracil. Biochem J. 1992 Nov 1;287(Pt 3):1007–1010. doi: 10.1042/bj2871007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. V. Herpes simplex virus-induced dUTPase: target site for antiviral chemotherapy. Virology. 1988 Sep;166(1):262–264. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]