Abstract

We have previously shown that mice lacking the TSH receptor (TSHR) exhibit osteoporosis due to enhanced osteoclast formation. The fact that this enhancement is not observed in double-null mice of TSHR and TNFα suggests that TNFα overexpression in osteoclast progenitors (macrophages) may be involved. It is unknown how TNFα expression is regulated in osteoclastogenesis. Here, we describe a receptor activator for nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL)-responsive sequence (CCG AGA CAG AGG TGT AGG GCC), spanning from −157 to −137 bp of the 5′-flanking region of the TNFα gene, which functions as a cis-acting regulatory element. We further show how RANKL treatment stimulates the high-mobility group box proteins (HMGB) HMGB1 and HMGB2 to bind the RANKL-responsive sequence and up-regulates TNFα transcription. Exogenous HMGB elicits the expression of cytokines, including TNFα, as well as osteoclast formation. Conversely, TSH inhibits the expression of HMGB and TNFα and the formation of osteoclasts. These results suggest that HMGB play a pivotal role in osteoclastogenesis. We also show a direct correlation between the expression of HMGB and TNFα and osteoclast formation in TSHR-null mice and TNFα-null mice. Taken together, we conclude that HMGB and TNFα play critical roles in the regulation of osteoclastogenesis and the remodeling of bone.

THYROID HORMONES (TH) affect bone metabolism by stimulating bone resorption directly and indirectly through osteoblast activity (1,2,3). Our recent study of genetically manipulated mice showed that in addition to TH, TSH also plays a role in bone remodeling (4). TSH receptors (TSHR) are expressed in osteoclasts and osteoblasts, and TSH negatively regulates bone remodeling by decreasing the production of TNFα in osteoclasts (5). Thus, double-knockout mice lacking both TSHR and TNFα do not exhibit enhanced osteoclast formation or osteoporosis. Interestingly, the two types of thyroid receptor (TRα and TRβ)-null mice display different pathological bone phenotypes even though they have normal or slightly elevated TSH levels (6,7,8). The TRα-null mice exhibit osteosclerosis, but the TRβ-null mice exhibit osteoporosis. Clearly, the functional roles of TH and TSH in bone remodeling are not completely understood.

TNFα has long been studied under pathophysiological conditions such as autoimmune disease, infection, and inflammation (9,10). Recent studies have shown that estrogen directly inhibits osteoclast formation by stimulating Fas ligand expression (11). It also functions indirectly by suppressing TNFα production in T cells (12,13). Thus, estrogen withdrawal does not cause osteoporosis in nu/nu (T cell-deficient mice), TNFα−/−, or TNFα receptor−/− mice (14). We have recently obtained similar findings from parallel studies that indicate that the enhanced osteoclast formation seen in TSHR+/− and TSHR−/− mice is a result of TNFα overproduction (5), despite the fact that the cellular mechanism of TNFα production differs from that of estrogen withdrawal. Both TSHR+/− and TSHR−/− mice overproduce TNFα in osteoclast progenitors such as macrophages but not in T cells. Recombinant TSH inhibits both cell proliferation and TNFα expression in these progenitors (5). In contrast to osteoclast inhibition by TSH, FSH stimulates TNFα production and osteoclast formation (15,16). Thus, in FSHβ+/− and FSHβ−/− mice, osteoclast formation is suppressed and bone mass is increased, suggesting again that TNFα is playing a regulatory role in bone remodeling. Specifically, TNFα increases osteoclast progenitor numbers in bone marrow, as observed in TNFα transgenic mice and mice in which TNFα is administered (17,18).

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA), and TNFα itself are stimulators of endogenous TNFα expression in macrophages, B cells, and T cells (19,20,21,22). TNFα expression is regulated at the transcriptional level by several mechanisms. For example, the 5′-flanking region of the TNFα gene contains several nuclear factor (NF)-κB-like motifs between −0.2 and −0.6 kb that are considered to be LPS cis-acting regulatory elements (see Fig. 2A) (23). Recently, however, the LPS-induced regulatory element LPS-induced TNFα promoter (LITAF) and its associated proteins have also been identified in the human TNFα promoter (19). PMA stimulates the 5′-flanking sequence between −65 and −120 bp in the TNFα gene, which consists of putative activator protein-1 (AP-1) and cAMP-responsive element (CRE) binding sites (Fig. 2A) (21,22); however, there are no other studies that have explored this transcriptional regulatory mechanism in osteoclastogenesis. We have previously shown that the receptor activator for NF-κB ligand (RANKL) stimulates endogenous TNFα expression during osteoclastogenesis and is necessary for osteoclast formation (5). Furthermore, RANKL and a mixture of IL-1 and TNFα, as well as the macrophage activator PMA, increase murine TNFα promoter activity.

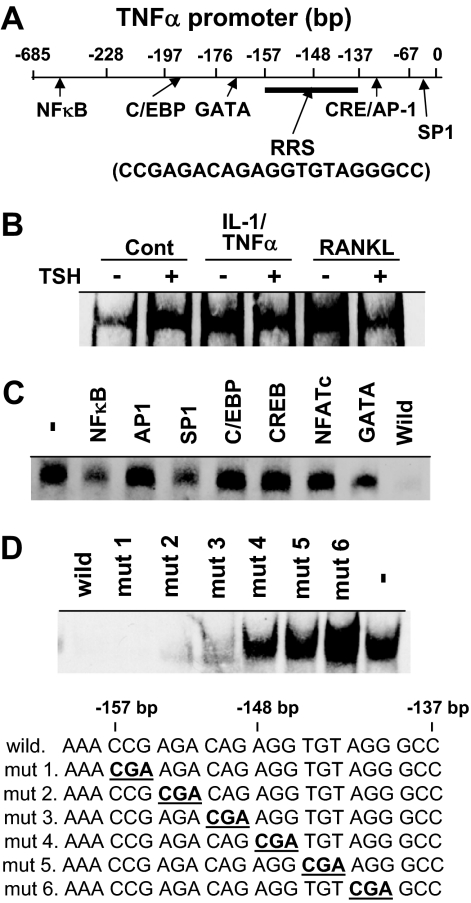

Figure 2.

TNFα Promoter and Binding of Nuclear Factors to the RRS

A, The location of the novel RRS between −157 and −137 bp (CCGAGACAGAGGTGTAGGGCC) on the TNFα promoter in relation to established transcriptional factor binding sites. B, RAW-C3 cells were treated with vehicle (Cont), a mixture of IL-1 (10 ng/ml) and TNFα (50 ng/ml) (IL-1/TNFα), or RANKL (100 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of TSH (200 ng/ml), and nuclear fractions were prepared for the incubation with biotin-labeled RRS for EMSA. C, Nuclear fractions of RAW-C3 cells treated with RANKL were incubated with biotin-labeled RRS with or without a 500 times higher concentration of consensus oligonucleotides for NF-κB, AP-1, SP-1, C/EBP, CREB, NFATc, GATA, and RRS (wild) for the EMSA. Nuclear binding of biotin-RRS in the absence of unlabeled oligonucleotide is denoted as −. D, Nuclear fractions from RAW-C3 cells treated with RANKL (100 ng/ml) were incubated with biotin-labeled RRS and 500-fold excess amounts of natural (wild) or mutated RRS (mut 1 to mut 6). Protein-DNA binding was measured by EMSA. Protein binding in the absence of nonlabeled oligonucleotide is denoted as −. Mutated sequences are described in bold and underlined.

The high-mobility group (HMG) proteins are a family of low-molecular-weight and nonhistone chromatin-associated proteins that regulate the processes of transcription, replication, recombination, and DNA repair (24,25,26). There are three groups of HMG proteins, namely HMGA, HMGB, and HMGN. HMGB1 and HMGB2 are highly homologous (∼80%) 25- to 30-kDa proteins that belong to the HMGB subgroup of the HMG proteins. Both HMGB1 (amphoterin) and HMGB2 contain a highly acidic C-terminal region. Unlike HMGB2, the HMGB1 protein is highly expressed in all cell types during embryonic and postnatal life (25). HMGB1 is secreted by an atypical endolysosomal-like pathway in response to bacterial infection and inflammation (27,28). HMGB1-knockout mice die just after birth due to hypoglycemia (29). A recent study has shown that HMGB1-null mice displayed impaired skeletal development due to a lack of HMGB1 expression in hyperchondrocytes (30). In adult life, the HMGB2 protein and its mRNA are highly expressed only in certain tissues such as the thymus, spleen, and testis. Mice deprived of HMGB2 continue to survive into adulthood, although impaired spermatogenesis has been reported (31). Here we provide the first direct evidence that TSH regulates HMGB and TNFα expression in osteoclastogenesis through a novel DNA sequence.

RESULTS

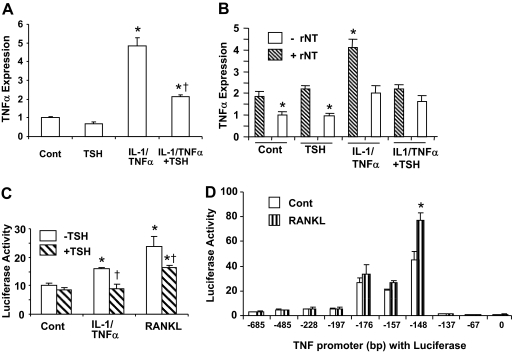

Transcriptional Regulation of TNFα Expression by TSH in Macrophages

We have previously reported that the increase in osteoclast formation seen in TSHR−/− mice is due to TNFα overexpression in osteoclast progenitors and that IL-1/TNFα, as well as RANKL directly increases TNFα expression (5). Figure 1A shows that IL-1/TNFα treatment increases TNFα expression in RAW-C3 cells. This increase is significantly reduced in the presence of TSH, suggesting that TSH is indeed negatively regulating the levels of cytokines known to be involved in osteoporosis. To further examine whether the effects of IL-1/TNFα and TSH on TNFα expression are due to the regulation of TNFα transcription, we performed a PCR-based run-on assay and a luciferase promoter assay. Figure 1B clearly shows that TNFα transcriptional activity, as measured by the PCR-based run-on assay, increased 2-fold in cultures of RAW-C3 cells after IL-1/TNFα treatment, but that this increase was ameliorated by the presence of TSH. This result further suggests that TSH is attenuating the effect of IL-1/TNFα. The absence of the ribonucleotides (rNT) in negative controls results in consistently lower TNFα mRNA expression than in either treated or untreated samples incubated with rNT. Treatment with RANKL (100 ng/ml) and IL-1/TNFα (a mixture of 10 ng/ml IL-1 and 50 ng/ml TNFα) significantly increased luciferase activity in RAW-C3 cells stably transfected with the TNFα promoter-luciferase construct (−176 bp-Luc), but this activity was attenuated by TSH treatment (Fig. 1C). This result indicates that TNFα expression is indeed regulated at the transcriptional level by cytokines (RANKL and IL-1/TNFα) and at least one hormone (TSH). Unless otherwise described, we used the same doses of RANKL (100 ng/ml) and IL-1/TNFα (a mixture of 10 ng/ml IL-1 and 50 ng/ml TNFα) in all experiments using RAW-C3 cells.

Figure 1.

Regulation of TNFα Expression and Transcription

A, RAW-C3 cells were treated with vehicle (Cont), TSH (200 ng/ml), a mixture of IL-1 (10 ng/ml) and TNFα (50 ng/ml), or a mixture of IL-1 (10 ng/ml) and TNFα (50 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of TSH (200 ng/ml) for 6 h, and TNFα mRNA expression was examined. Levels of TNFα expression were compared between treated and control groups (*, P < 0.05) or between IL-1/TNFα and IL-1/TNFα plus TSH treatments (†, P < 0.05). B, TNFα mRNA expression as measured by PCR-based run-on assay. RAW-C3 cells were treated as described above and as detailed in Materials and Methods. Nuclear fractions incubated without rNT were used as negative controls, and TNFα expression levels are described as a ratio to controls; *, P < 0.05. C, The effects of cytokines and hormones on TNFα transcription were examined in stably transfected RAW-C3 cells expressing −176 bp-Luc. Cells were treated with vehicle, RANKL (100 ng/ml), or a mixture of IL-1 (10 ng/ml) and TNFα (50 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of TSH (200 ng/ml). Luciferase activity was measured after 6 h for all samples except the RANKL-treated sample, which was measured after 12 h. Luciferase activity was compared between treated and control groups (*, P < 0.05) and between treated groups in the absence or presence of TSH (†, P < 0.05). D, The 5′-deletion constructs of the TNFα promoter (from 0, −67, −137, −148, −157, −176, −197, −228, −485, or −685 bp to +115 bp) with luciferase were transiently transfected into RAW-C3 cells and treated with either vehicle or RANKL (100 ng/ml) for 12 h and luciferase activity measured. The results shown here were replicated at least twice. Luciferase activity was compared between control and RANKL-treated groups (*, P < 0.05).

Although it has been previously suggested that NF-κB, AP-1, and LPS-induced TNFα promoter (LITAF) proteins are involved in the regulation of TNFα promoter activity induced by PMA and LPS (18,19,20), the functional roles of these proteins have been inadequately studied in macrophages. We therefore examined murine TNFα transcriptional regulation in detail using 5′-deletion constructs of the TNFα promoter coupled to the luciferase reporter gene pGL3 in RAW-C3 cells. Cells were stimulated for 12 h with or without RANKL, and luciferase activity was measured (Fig. 1D). The basal activity of the TNFα promoter begins from −137 bp, peaks at −148 bp, and declines by −157 bp. We found that RANKL treatment specifically enhanced the promoter activity of the −148 bp-Luc construct. These data suggest that RANKL-responsive sequence (RRS) in the TNFα promoter is located between −157 and −137 bp (CCG AGA CAG AGG TGT AGG GCC) (Fig. 2A).

We further examined the regulatory role of the RRS in TNFα transcription by investigating whether transcription factor(s) bind to the sequence. Nuclear fractions from RANKL- or IL-1/TNFα-treated RAW-C3 cells were incubated with biotin-labeled RRS, and samples were analyzed by EMSA. DNA-protein complexes from untreated RAW-C3 cells were used as controls (Fig. 2B). We found that these cytokines, specifically RANKL, increased protein binding to RRS. TSH inhibited this binding, indicating that the protein responsible may be stimulated by cytokines during transcription or translocation from cytoplasm to the nucleus or by DNA binding in the nucleus. Interestingly, the NF-κB and SP-1 consensus nucleotide sequences partially competed with RRS for protein binding, but AP-1, NFATc, C/EBP, GATA, and CREB consensus sequences did not (Fig. 2C). In addition, mutation analysis indicated the sequence downstream of the 12th nucleotide (AGG TGT AGG GCC) between −148 and −137 bp on the RRS was required for protein binding (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, this sequence was identical to the one that exhibited a sharp increase in luciferase activity (Fig. 1D).

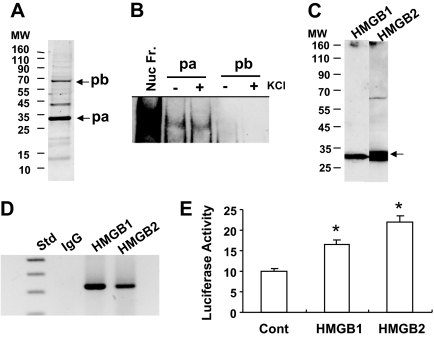

Purification and Identification of the RRS Binding Proteins

In an attempt to purify the nuclear transcription factor(s) bound to the RRS, nuclear fractions from RANKL-treated RAW-C3 cells were applied to a RRS-bound streptavidin gel affinity column. Bound protein(s) were eluted by high salt (150 mm KCl) and detected on a 4–20% SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A). The major proteins in the eluate emerged at about 30 kDa (labeled pa in Fig. 3A). Two other minor proteins emerged at about 40 and 65 kDa (labeled pb in Fig. 3A). After the approximately 30- and 65-kDa proteins were electroeluted from the gel, their ability to bind to the RRS was tested (Fig. 3B). We found that the approximately 30-kDa protein binds to the RRS to create a complex with the same mobility as that formed in the presence of the crude nuclear fraction from RAW-C3 cells. The approximately 65-kDa protein, however, was unable to bind to the RRS even in the presence of 100 mm KCl, an enhancer of protein binding (Fig. 3B). Mass spectrometry analysis of the trypsin-digested proteins indicated that the approximately 30-kDa band was composed of both HMGB1 (HMG box protein 1) and HMGB2, designated by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) accession numbers 600761 and 6680229, respectively. We also identified a 29-kDa cytokine-induced protein in the eluate with NCBI number 13384730, as well as several other protein fragments with various molecular masses. The 65-kDa protein was found to be the pigpen nuclear protein (NCBI accession number 7920331). It is reported to be expressed in craniofacial morphogenesis (32).

Figure 3.

Purification of RRS Binding Protein(s) and Verification of HMGB

A, Proteins purified in an affinity column were run on 4–20% SDS-PAGE and silver stained. The major protein appeared at about 30 kDa (pa), and two other minor proteins appeared at about 40 and about 65 kDa (pb). B, The proteins pa and pb shown in Fig. 3A were electroeluted from the gel and applied to EMSA using biotin-RRS oligonucleotide in the presence or absence of 100 mm KCl. Nuclear fractions from RAW-C3 cells treated with RANKL (100 ng/ml) were used as a positive control. C, Affinity-purified proteins were subjected to Western blotting with anti-HMGB1 and anti-HMGB2 antibody. The expected sizes of the HMGB proteins are indicated by an arrow. D, ChIP analysis. RAW-C3 cells treated with RANKL (100 ng/ml) were prepared for ChIP assay as detailed in the Materials and Methods, and DNAs precipitated with the anti-HMGB1 and -HMGB2 antibody were PCR amplified using a specific primer set. E, The plasmids pcDNA3.1/His (Cont), pcDNA3.1/His-HMGB1 (HMGB1), or pcDNA3.1/His-HMGB2 (HMGB2) were transiently transfected into RAW-C3 cells expressing the TNFα promoter −176 bp-Luc, and luciferase activity was measured 12 h after transfection. Luciferase activity was compared among the control and HMGB-expressing groups (*, P < 0.05).

To confirm that the purified proteins that emerged at about 30 kDa were indeed HMGB1 and HMGB2, we performed Western blot analysis and the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. As shown in Fig. 3C, HMGB1 and HMGB2 antibodies cross-reacted with the approximately 30-kDa protein in the purified protein fraction on the Western blot. Importantly, ChIP assay indicated that both HMGB1 and HMGB2 bound to the RRS in the TNFα promoter in RAW-C3 cells (Fig. 3D). To further test the effects of HMGB on TNFα transcription, we transiently transfected with HMGB1 and HMGB2 expression plasmids into RAW-C3 cells stably transfected with −176 bp-Luc, and luciferase activity was measured (Fig. 3E). We found that overexpression of both HMGB1 and HMGB2 enhanced TNFα promoter-generated luciferase activity. This result suggests that HMGB1 and HMGB2 regulate TNFα transcription by binding to the RRS on the TNFα promoter.

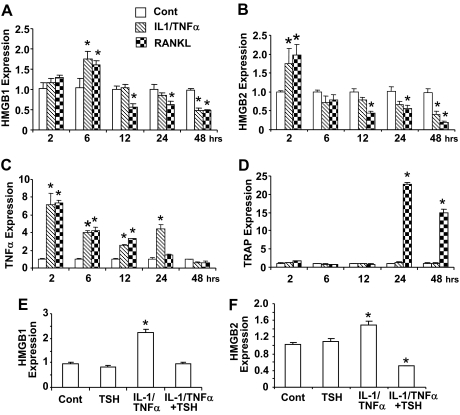

HMGB Expression Is Required for TNFα Expression and Osteoclast Formation

We next studied the effect of HMGB1 and HMGB2 expression on TNFα regulation and osteoclast formation. We hypothesized that HMGB are required for endogenous TNFα expression and osteoclast formation and that under- or overexpressing HMGB would alter both these processes. We demonstrated a time-dependent effect of HMGB and TNFα on the expression of the osteoclast marker tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) in RAW-C3 cells (Fig. 4). Our results indicated that both HMGB1 and HMGB2 were transiently stimulated at 6 and 2 h, respectively, by IL-1/TNFα or RANKL treatments and that the expression of both HMGB decreased after 12 h of treatment (Fig. 4, A and B). TNFα expression increased after 2 h of treatments with IL-1/TNFα or RANKL, and this increase was sustained for 24 h after treatment (Fig. 4C). The expression of the early-stage osteoclast marker TRAP increased sharply 24 h after RANKL but not after IL-1/TNFα treatment (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, TSH inhibited IL-1/TNFα-induced expression of both HMGB1 and HMGB2 (Fig. 4, E and F), suggesting that TSH affects the expression of both HMGB1 and HMGB2 as well as downstream events in osteoclastogenesis.

Figure 4.

HMGB1 and HMGB2 Gene Expression in RAW-C3 Cells Treated with IL-1/TNFα, RANKL, and IL-1/TNFα Plus TSH.

A–D, RAW-C3 cells were stimulated with vehicle, a mixture of IL-1 (10 ng/ml) and TNFα (50 ng/ml) (IL-1/TNF), or RANKL (100 ng/ml) for 2, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h. Time-dependent gene expression of HMGB1 (A), HMGB2 (B), TNFα (C), and the osteoclast marker TRAP (D) were measured by real-time PCR. E and F, HMGB1 (E) and HMGB2 (F) expression was measured after treatments with either vehicle or IL-1/TNFα and in the presence or absence of TSH (200 g/ml). All data are presented as means ± sem. *, P < 0.05.

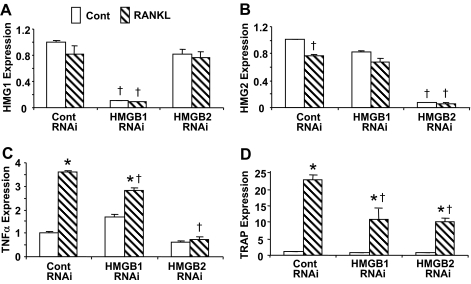

We next examined whether the expression of the HMGB is crucial for TNFα expression and osteoclast formation. RAW-C3 cells were transiently transfected with small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeted to either HMGB1 or HMGB2, and RANKL-induced expression of TNFα and TRAP was assessed (Fig. 5). We found that although transient transfection of the siRNA specifically abolished their mRNA expression after 2 h regardless of the presence or absence of RANKL (Fig. 5, A and B), their expression levels returned to that of controls within 6 h (data not shown). Transient loss of either HMGB1 or -2 expression significantly attenuated RANKL-induced TNFα mRNA expression (Fig. 5C), although the inhibition was greater with HMGB2-targeted siRNA than with siRNA targeted to HMGB1. Consistent with the decrease in TNFα expression, RANKL-induced TRAP expression detected after 24 h of treatment was suppressed approximately 50% by HMGB1 and HMGB2 siRNA (Fig. 5D). These results indicate that the expression of both HMGB1 and HMGB2 is required for TNFα and TRAP expression and osteoclastogenesis.

Figure 5.

Effects of HMGB Knockdown on TNFα and TRAP Expression

RAW-C3 cells were transiently transfected with control (Cont) or HMGB1 or HMGB2 siRNA (RNAi) and then HMGB1 (A), HMGB2 (B), TNFα (C), and TRAP (D) expression were examined after stimulation with RANKL (100 ng/ml) by real-time PCR. The expression levels were compared among groups treated with or without RANKL (*, P < 0.05), and groups transfected with control RNAi and HMGB1 RNAi or HMGB2 RNAi (†, P < 0.05).

Cellular Distribution of HMGB and Their Binding to the RRS in the Nucleus

The HMGB proteins are found mainly in the nucleus. However, only a small fraction of these nuclear HMGB proteins are likely to be bound to the RRS on the TNFα promoter. Immunostaining indicates that HMGB1 and HMGB2 are expressed in a distinct location within the cell under basal conditions (Fig. 6A). HMGB1 was highly localized in the nucleoli, whereas HMGB2 was found primarily in the nucleus and the cytoplasm. We next used Western blot analysis to assess the expression levels of total vs. RRS-bound HMGB in RAW-C3 cells treated with and without RANKL, as detailed in Materials and Methods. Here, we semiquantitatively measured the amounts of HMGB that have the potential to bind to the RRS. We found that there are no clear changes in total HMGB expression (immunoblot) in the nucleus between treated and untreated RAW-C3 cells; however, RRS-bound HMGB protein (immunoprecipitation) was markedly (from minimal to very high intensity) increased by RANKL treatment (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Localization and RRS Binding of HMGB

A, Localization of HMGB proteins in RAW-C3 cells by immunostaining: HMGB1 (b, e, and h) and HMGB2 (c, f, and i). IgG was used as a negative control (a, d, and g). 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole was used for nuclear staining. Arrows indicate staining of HMGB1 protein in the nucleoli. B, Expression of total and RRS-bound (DAPI) HMGB in the nuclei of RAW-C3 cells treated with RANKL (100 ng/ml). Total HMGB expression (IB) was measured by directly analyzing the nuclear fractions on Western blot. To measure the expression of RRS-bound HMGB (IP), nuclear fractions were incubated with biotin-labeled RRS and then with streptavidin agarose beads. Samples were then subjected to Western blotting with anti-HMGB antibodies. The expected sizes of HMGB1 and HMGB2 proteins are indicated by arrowheads and arrows, respectively. C, Recombinant (r) HMGB1 and HMGB2 at 70 and 200 ng/lane doses, with or without nuclear fractions from RAW-C3 cells, were incubated with biotin-labeled RRS for EMSA. IB, Immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation.

We further confirmed the binding of HMGB to the RRS by using generated recombinant proteins (Fig. 6C). Both recombinant HMGB1 and HMGB2 bound to the RRS to create complexes with the same migration rates as those present in the crude nuclear fraction from RAW-C3 cells. These results strongly supported the idea that RANKL treatment stimulates HMGB to bind to the RRS on the TNFα promoter, possibly increasing TNFα and TRAP expression and enhancing osteoclastogenesis.

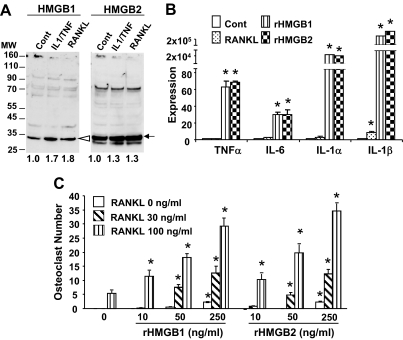

Secretion of HMGB and Exogenous Effects of HMGB on Cytokine Expression and Osteoclast Formation

It has been established that HMGB are secreted by macrophages (27,28). The HMGB are also secreted by RAW-C3 cells under basal conditions. HMGB1 secretion, in particular, is enhanced in RAW-C3 cells treated with IL-1/TNFα and RANKL (Figs. 7A). To understand the functional significance of the secreted HMGB, we measured cytokine expression and osteoclast formation by counting TRAP-positive cells in RAW-C3 cell cultures. Treatment with either recombinant HMGB1 or HMGB2 altered RAW-C3 cell morphology in a dose-dependent manner at doses ranging from 10–250 ng/ml. Furthermore, these doses stimulated the expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in a positive-feedback manner (Fig. 7B). Although 250 ng/ml of recombinant HMGB1 and HMGB2 alone induces a small number of TRAP-positive osteoclasts, the same dose contributes to a robust stimulation of osteoclast formation in the presence of RANKL (Fig. 7C). Similar but marginal enhancements of TRAP expression and osteoclast formation were observed in bone marrow macrophage cultures after HMGB treatment (Fig. 8C), suggesting that extracellular HMGB play an important role in cytokine expression and osteoclastogenesis.

Figure 7.

Secretion of HMGB by RAW-C3 Cells and Their Effect on Cytokine Expression and Osteoclast Formation

A, RAW-C3 cells were cultured with a combination of IL-1 (10 ng/ml) and TNFα (50 ng/ml) (IL-1/TNF) or RANKL (100 ng/ml) for 2 d, and cell supernatants were Western blotted with anti-HMGB1 or -HMGB2 antibody. Band intensities were measured and are expressed as a ratio to control. The expected sizes of HMGB1 and HMGB2 are indicated by arrowheads and arrows, respectively. B, RAW-C3 cells were treated with RANKL (100 ng/ml), recombinant (r) HMGB1 (250 ng/ml) or rHMG2 (250 ng/ml) for 6 h, and the gene expression of TNFα, IL-6, and IL-1α and -1β was determined by real-time PCR. Expression levels were compared between treated and untreated groups; *, P < 0.05. C, RAW-C3 cells were treated with RANKL (30 and 100 ng/ml) alone or RANKL with rHMGB1 or rHMG2 (10, 50, and 250 ng/ml) for 6 d, and TRAP-positive osteoclast formation was assessed. Comparisons were made between cells treated with RANKL alone or RANKL plus HMGB; *, P < 0.05.

Figure 8.

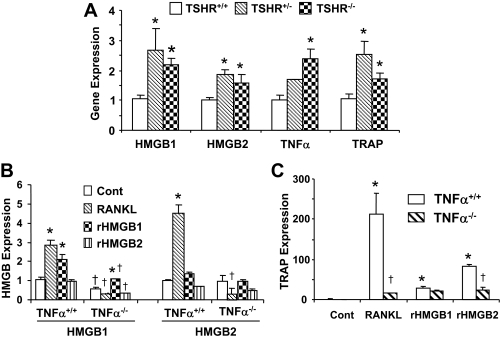

HMGB and TRAP Expression in Bone Marrow of TSHR- or TNFα-Null Mice

A, Bone marrow macrophages from TSHR+/+, TSHR+/−, and TSHR−/− mice were cultured with RANKL (100 ng/ml) for 24 h, and HMGB1, HMGB2, TNFα, and TRAP expression levels were analyzed by real-time PCR. Comparisons were made between TSHR+/+, TSHR+/−, and TSHR−/− mice; *, P < 0.05. B and C, Bone marrow macrophages from TNFα+/+ and TNFα−/− mice were cultured with vehicle, RANKL (100 ng/ml), recombinant (r) HMGB1 (250 ng/ml) or rHMGB2 (250 ng/ml) for 24 h and HMGB1 and HMGB2 expression (B) or TRAP expression (C) was analyzed by real-time PCR. *, P < 0.05; comparisons made between TNFα+/+ or TNFα−/− mice treated with vehicle, RANKL, rHMGB1, or rHMGB2. †, P < 0.05; comparisons in each treatment group made between TNFα+/+ and TNFα−/− mice.

Differential Temporal Expression of HMGB and TNFα in Osteoclastogenesis in Animal Models

We have demonstrated that changes in the expression of HMGB1 and HMGB2 affect both TNFα expression and osteoclastogenesis in RAW-C3 cells (Fig. 5). We reasoned that if HMGB are really vital for these processes, there should be a direct relationship between HMGB expression and TNFα expression and osteoclast formation in vivo or ex vivo. To explore this possibility, we used animal models over- or underexpressing the TNFα gene. Bone marrow macrophages derived from TSHR+/− and TSHR−/− mice, which exhibit enhanced TNFα and osteoclast formation (4,5), were cultured with RANKL or with recombinant HMGB, and the expression levels of HMGB1 and HMGB2 were measured by real-time PCR. As expected, expression of both HMGB1 and HMGB2 was significantly increased in TSHR+/− and TSHR−/− mice, and this increase paralleled increases in TNFα and TRAP expression, a direct indicator of osteoclastogenesis (Fig. 8A). Also, as predicted, we found a significant reduction in HMGB expression in bone marrow macrophage cultures from TNFα−/− mice (Fig. 8B) and a significant reduction in TRAP expression (Fig. 8C) in the presence of RANKL and recombinant HMGB. The suppression of TRAP expression in bone marrow macrophage cultures from TNFα−/− mice may account for the observed decrease in the number of TRAP-positive osteoclasts and suggests that TNFα is playing a critical role in the increase in TRAP activity. The Student's t test revealed a significant difference (P < 0.05) between wild-type and TNFα knockout mice in the number of osteoclasts induced by RANKL (TNFα+/+ mice, 81.5 ± 3.9 per well; TNFα−/− mice, 21.2 ± 3.0 per well).

DISCUSSION

The proinflammatory cytokine TNFα is a member of the tumor necrosis family, and its expression is enhanced in autoimmune diseases and rheumatoid arthritis (9). It also plays a role in tissue damage and bone destruction (9,10). We previously found that TSHR-null mice exhibit increased TNFα expression in osteoclast progenitors. The fact that these mice develop osteoporosis (5) suggests that TNFα overproduction may play a major role in the development of this condition. Here we used a promoter assay and a PCR-based run-on assay to show that TSH directly down-regulates TNFα transcription induced by IL-1/TNFα or RANKL treatment (Fig. 1). Our results further support the idea that TSH is a key regulator of TNFα transcriptional activity and possibly of other downstream events in osteoclastogenesis and bone remodeling.

In an attempt to define the regulatory mechanism responsible for endogenous TNFα overexpression, we performed a deletion analysis of the murine TNFα promoter (Fig. 1D) followed by the EMSA to identify important binding protein(s). We show that the TNFα promoter contains a RRS required for the RANKL-induced increase in expression of a TNFα promoter-luciferase construct (Fig. 1D). Mutations in the RRS ameliorate protein binding from the crude nuclear fraction (Fig. 2D), and TSH inhibits TNFα transcriptional activity through the RRS (Fig. 2B). We next used a RRS-bound streptavidin gel affinity column and mass spectroscopy to identify HMGB1 and HMGB2 as RRS-binding proteins (Figs. 3D and 6, B and C). The fact that HMGB1 and HMGB2 overexpression in cells stimulates TNFα promoter activity (Fig. 3E) indicates that HMGB likely stimulate TNFα transcriptional activity in the nucleus of osteoclast progenitors.

The HMGB1 protein is ubiquitously expressed in all tissues. It is believed to mediate the body's response to bacterial infection, inflammation, sepsis, and tumor metastasis (33,34,35,36). Although this protein localizes to the nucleus (37), it is secreted in large amounts during chronic inflammation and sepsis in synovial fluids and the general circulation (38,39,40,41), and it affects both intra- and extracellular processes. HMGB2 expression, in contrast, is limited to the thymus, spleen, and testis in adults (31) and is required for normal spermatogenesis (31,42). Here we measured the levels of HMGB1 and HMGB2 mRNA and protein expression during osteoclastogenesis (Fig. 4, A and B). We found that the two proteins are not interchangeable. First, HMGB1 and HMGB2 exhibit different temporal profiles of expression after IL-1/TNF and RANKL treatment, perhaps because the genes are located on two separate chromosomes (chromosomes 5 and 8, respectively). Secondly, the subcellular distributions of HMGB1 and HMGB2 are different. HMGB1 is found mainly in the nucleoli, whereas HMGB2 is distributed in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm of RAW-C3 cells (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, in the testis, HMGB1 is highly expressed in spermatogonia, whereas HMGB2 is highly expressed in primary and secondary spermatocytes but weakly expressed in elongated spermatids (42). A lack of HMGB2 inhibits germ cell differentiation in seminiferous tubules and immobilizes spermatozoa, clearly indicating that HMGB2 is required for normal cell differentiation (31). Finally, we showed that both HMGB1 and HMGB2 are required for full TNFα expression and osteoclast formation (Fig. 5). Transfection with either HMGB1 or HMGB2 siRNA significantly suppressed TNFα expression and osteoclast formation.

These results suggest that although HMGB1 and HMGB2 are expressed in the same cells, they may very well have distinct spatial, temporal, and functional roles in osteoclastogenesis. Similar findings have been described in myeloid cells (41). Specifically, the functional role of HMGB in skeletal development has recently been published in detail (30). HMGB1-null embryos exhibit impaired endochondral ossification and impaired osteoclast invasion around the perichondrium in tibia, providing strong evidence of the importance of HMGB1 in chondrogenesis during bone development. However, it is still not clear which of the two proteins, HMGB1 or HMGB2, is the most critical for the regulation of osteoclastogenesis and bone remodeling. Furthermore, the functional role of HMGB on osteoblastogenesis and bone formation has not been established. Therefore, the ultimate goal is to define the function of HMGB in osteoclastogenesis and osteoblastogenesis using conditional knockout mice that allow the effect of each HMGB protein to be individually studied under a variety of conditions.

We have demonstrated with immunostaining, Western blotting, and ChIP analyses that both HMGB1 and HMGB2 are localized in the nuclei of RAW-C3 cells (Figs. 3D and 6, A and B). Both of these proteins are also secreted from osteoclast progenitors after RANKL stimulation (Fig. 7A), probably by an atypical endolysosomal-like process (27). Also, both proteins migrate to the RRS of the TNFα promoter and initiate TNFα transcription in response to RANKL treatment (Figs. 3D and 6B). We hypothesize that the enhanced ability of the HMGB to bind to this specific DNA sequence is probably due to phosphorylation as described for AP-1 (43) or by cross-talk with other factors or receptors such as estrogen receptors, p53, NF-κB, homeobox-containing proteins, or TATA-binding proteins (44,45). Our findings that the RRS is also weakly bound by NF-κB and SP-1 (Fig. 2C) further suggests an association of HMGB with other nuclear factors during trans-activation. More studies of these issues are needed to enhance our understanding of osteoclastogenesis during normal bone remodeling and in pathological conditions.

HMGB are known to bind the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) during intracellular signal transduction (46). RAGE is a member of the Ig superfamily, and it is implicated in the regulation of various disease processes such as tumor metastasis, diabetic complications, neurodegenerative disorders, atherosclerosis, and inflammation (35,47,48,49,50,51). In addition to HMGB1, several other factors including Mac1-integrin, AGEs, and S100/calgranulins (47,52) have been reported to be RAGE ligands. These factors facilitate NF-κB-mediated signals after binding to RAGE to increase cytokine expression in macrophages in vitro and in vivo (33). RAGE signaling is clearly important in normal bone remodeling; RAGE-null mice exhibit increased bone mass due to reduced osteoclast formation (53,54), possibly due to a blockade of intracellular signaling and subsequent cytokine production. Our preliminary results revealed that osteoclast stimulation by HMGB was completely inhibited by treatment with a RAGE-neutralizing antibody (data not shown). This finding strongly suggests that HMGB1 and HMGB2 act on the RAGE receptor in osteoclast progenitors and that the HMGB/RAGE complex modulates cytokine expression and affects osteoclastogenesis in pathological conditions.

Here we report a series of events stemming from the down-regulation of TSH that lead to the overproduction of TNFα. This overproduction is mediated by HMGB protein binding to the RRS in the TNFα promoter. NF-κB signaling is known to be primarily involved in TNFα-mediated inflammation and bone destruction (55). The administration of a peptide that specifically inhibits NF-κB activation by binding to the NF-κB-essential modulator domain at the C terminus of inhibitor of κB kinases, prevents inflammatory bone destruction with osteoclastogenesis in vivo (55). Likewise, the TNFα-mediated osteoporosis seen in hyperthyroidism may be prevented or ameliorated by the administration of HMGB inhibitors or TSH. In fact, the administration of TSH has been shown to increase bone mass by reducing osteoclastogenesis in animal models (56).

Here we use TSHR−/− mice to determine how TSH controls osteoclast formation in osteoporotic conditions. We provide evidence that in the absence TSHR expression, TNFα production increases and HMGB are up-regulated. HMGB then bind to the novel RRS in the TNFα promoter and enhance osteoclast formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cytokines and Animals

Recombinant murine IL-1α, murine TNFα, human RANKL, human macrophage colony-stimulating factor (MCSF), and human TSH were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ), Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), or Fitzgerald Industries (Concord, MA). TSHR+/+, TSHR+/−, and TSHR−/− mice were generated by Dr. Davies at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine (MSSM) (57) and were maintained in-house using standard protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at MSSM. TNFα−/− animals were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME).

siRNA Transfection and Gene Expression

Gene expression levels of TNFα, HMGB1, HMGB2, and TRAP in RAW-C3 cell cultures or bone marrow macrophage cultures were measured by real-time PCR using specific primer sets and iTaq SYBR Green Supermix with a ROX kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) (4,5). PCR products were amplified by HMGB1- and HMGB2-specific primer sets and were sequenced for confirmation. For the gene expression experiments, RAW-C3 cells were cultured with either 100 ng/ml RANKL or a mixture of 10 ng/ml IL-1 and 50 ng/ml TNFα (IL-1/TNFα) either in the presence or absence of TSH (200 ng/ml) at various time points, as described in the figure legends. Bone marrow cells from TSHR+/+, TSHR+/−, TSHR−/−, or TNFα−/− mice were cultured with 30 ng/ml MCSF and 60 ng/ml RANKL. To knock down the expression of HMGB1 and HMGB2, specific siRNAs (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were transfected into RAW-C3 cells using Trans-Neural transfection reagent (Mirus, Madison, WI), and the expression levels of HMGB1, HMGB2, TNFα, and TRAP were measured. Data are described as fold expression compared with control.

PCR-Based Run-On Assay and Luciferase Reporter Assay

TNFα gene transcription was examined by PCR-based nuclear run-on assay (58). RAW-C3 cells were treated with a mixture of IL-1 (10 ng/ml) and TNFα (50 ng/ml) either with or without TSH (200 ng/ml) for 6 h. Nuclear fractions were prepared from each group and incubated with (+) or without (−) 2.5 mm rNT triphosphates (rATP, rUTP, rCTP, and rGTP) in the presence of 30 mm Tris buffer (pH 8.0), 20% glycerol, 150 mm KCl, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and 40 U RNasin for 30 min at 4 C. TNFα expression levels in each sample were quantified by real-time PCR using a specific primer set and described as a ratio to the control without rNT.

5′-Deletion constructs of murine TNFα promoter were PCR amplified and subcloned into a pGL3 basic luciferase plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI) for the measurement of transcriptional activities. Namely, −67 bp-Luc (contains −67 to +115 bp from transcription initiation site of TNFα gene), −137 bp-Luc (−137 to +115 bp), −148 bp-Luc (−148 to +115 bp), −157 bp-Luc (−157 to +115 bp), −176 bp-Luc (−176 to +115 bp), −197 bp-Luc (−197 to +115 bp), −228 bp-Luc (−228 to +115 bp), −485 bp-Luc (−485 to +115 bp), and −685 bp-Luc (−685 to +115 bp) were used for these experiments. These plasmids were transiently transfected with a Renilla luciferase plasmid into RAW-C3 cells using Trans-Neural transfection reagent (Mirus), and luciferase activities were measured by a Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay kit (Promega). In a separate experiment, the effect of cytokines and hormones on TNFα promoter activity was examined using RAW-C3 cells stably transfected with −176 bp-Luc (RAW-C3 cells with −176 bp-Luc). RANKL (100 ng/ml), or a mixture of IL-1 (10 ng/ml) and TNFα (50 ng/ml) either in the presence or absence of TSH (200 ng/ml) were added for 6 h (IL-1/TNF) or 12 h (RANKL), and luciferase activities were measured. To examine the effect of HMGB overexpression on TNFα promoter activity, murine HMGB1 or HMGB2 gene in pcDNA3.1/His plasmids (Invitrogen) was transiently transfected into RAW-C3 with −176 bp-Luc, as described above, and luciferase activity was measured. Finally, luciferase activities were normalized to the total protein content in each sample.

EMSA

Nuclear fractions prepared from RAW-C3 cells were incubated with biotin-labeled RRS (CCG AGA CAG AGG TGT AGG GCC in Fig. 2A) and applied on a 6% native acrylamide gel containing 2.5% glycerol in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (0.05 m Tris, pH 7.4). Biotin-labeled RRS was generated by a DNA 3′-end labeling kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) or obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). To examine binding specificity, nuclear fractions were incubated with biotin-labeled RRS with or without a 500 times higher concentration of consensus sequences of NF-κB (AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC), SP-1 (ATTCGATCGGGGCGGGGCGAGC), AP-1 (CGCTTGATGAGTCAGCCGGAA), NFATC (CGCCCAAAGAGGAAAATTTGTTTCATA), CREB (AGAGATTGCCTGACGTCAGAGAGCTAG), C/EBP (TGCAGATTGCGCAATCTGCA), and GATA (CCCCCGCGATGGAGAAGA). To map the minimum DNA sequence responsible for protein binding along the RRS, we analyzed a series of mutated RRS and wild-type control (see Fig. 2D for details) by the EMSA. Specifically, nuclear fractions from RAW-C3 cells were incubated with 500 times excess amounts of wild-type or mutated sequences with biotin-labeled RRS for the EMSA. Furthermore, the binding of recombinant HMGB1 and HMGB2 proteins to the RRS was also examined. LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Pierce) was used to detect biotin-labeled signals.

ChIP Assay

The ChIP assay was performed using the Chromatin Immuno-Precipitation kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Grand Island, NY) with minor modifications. RAW-C3 cells (107) were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at 37 C and collected in PBS (200 μl) containing protease cocktail inhibitors (Roche). Cell suspensions were sonicated for DNA fragmentation and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. Supernatants containing soluble DNA were diluted with ChIP dilution buffer and incubated with protein A agarose slurry and anti-HMGB1 or anti-HMGB2 antibody (Santa Cruz) overnight at 4 C. Nonimmune goat IgG (2 μg; Zymed, South San Francisco, CA) was used for a nonspecific binding. DNA-protein-antibody complex bound to agarose beads was eluted in the elution buffer by heating at 65 C for 5 h and treated first with RNase A and then with proteinase K. The purified DNA was amplified for the detection of TNFα promoter sequence containing RRS (between −197 and +115 bp) by PCR using a primer set (forward, CCCTCGAGGGCCAACTTTCCAAA; reverse, TGAGTGAAAGGGACAGAACCTGCCTG).

Purification and Sequencing of Binding Proteins

An RRS-bound affinity column was made by adding the annealed biotin-labeled RRS to a streptavidin gel column (1 ml; Pierce). Nuclear samples mixed with calf thymus DNA (5 μg) were applied to the column, and bound proteins were eluted with 10 ml 10 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mm KCl and 2.5% glycerol. Eluted proteins were applied to a 4–20% SDS-PAGE for the determination of molecular weights. Proteins with about 30 (major) and about 65 kDa (minor) on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A) were further analyzed for their ability to bind the RRS by EMSA and amino acid sequencing by mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometry was performed in both the Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences at MSSM and at the Protein Core Facility at Columbia University (New York, NY). Briefly, proteins digested with trypsin (100 ng/band in 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate) were extracted using Porus 20 R2 beads (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in a mixture of 5% formic acid and 0.2% trifluoroacetic acid and then applied to a MicroPro-HPLC system (Eldex Laboratories, Inc., Napa, CA) with a Magic C18 column (Michron BioResources, Inc., Auburn, CA) (59,60). Proteins were identified by their peptide molecular masses and MS/MS fragment spectra searched in the NCBI NR DNA/protein sequence database using Sonar.

Western Blotting and Immunostaining (HMGB Proteins)

HMGB1 and HMGB2 protein expression in nuclear fractions and in cell culture supernatants of RAW-C3 cells was determined by Western blot and immunostaining using rabbit anti-HMGB1 or goat anti-HMGB2 antibody (Santa Cruz). To measure the amounts of HMGB that have the potential to bind to the RRS, nuclear fractions prepared from RAW-C3 cells were incubated with annealed biotin-RRS oligonucleotide for 20 min at room temperature and then incubated with streptavidin-agarose beads for 2 h at 4 C. Finally, HMGB1 and HMGB2 proteins bound to the beads were analyzed on Western blot. To examine the endogenous expression of HMGB1 and HMGB2 proteins, RAW-C3 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, treated with 0.2% Triton X-100, and incubated with HMGB1 or HMGB2 antibody. Donkey antigoat IgG IRDye 800CW (Licor, Lincoln, NE) or goat antirabbit IgG IR680 (Invitrogen) antibody was used as secondary antibody for Western blot. Alexa 488-labeled donkey antigoat IgG antibody (Invitrogen) was used for immunostaining. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole was used for nuclear staining.

Generation of Recombinant HMGB Proteins and Their Effects on Cytokine Expression and Osteoclast Formation

Full-length murine HMGB1 (1.14 kb) and HMGB2 cDNAs (1.20 kb) were PCR amplified using cDNA generated from murine testis and subcloned into a pCAL-n vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) for the generation of calmodulin-binding peptide-tagged fusion proteins. PCR products were sequenced for confirmation. The CAL-HMGB1 and CAL-HMGB2 fusion plasmids were transformed into BL21 (DE3) and incubated with 0.2 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 4 h at 37 C for the induction of recombinant fusion protein. Bacterially generated HMGB proteins were incubated with lysozyme (200 μg/ml) in calcium-containing buffer [50 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm dithiothreitol, 1 mm magnesium acetate, 1 mm imidazole, and 2 mm CaCl2] for 30 min and sonicated for 20 min. After centrifugation of the cell suspension at 14,000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was mixed by rotation with calmodulin affinity resin (Stratagene) for 5 h at 4 C, and the resin was washed once with high-salt (300 mm NaCl) calcium-containing buffer and again with low-salt (150 mm NaCl) calcium-containing buffer. To obtain the CAL-free HMGB proteins, the resin was incubated with biotinylated thrombin (10 U) in thrombin cleavage buffer (1 ml; Invitrogen) for 14 h at 4 C and then with streptavidin agarose beads for 2 h at 4 C to remove biotinylated thrombin. Finally, the supernatants containing CAL-free recombinant HMGB were concentrated by Centricon TM-10 (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and were used as recombinant HMGB1 or HMGB2.

Recombinant CAL-free HMGB1 and HMGB2 protein emerged at an approximately 28-kDa molecular mass on SDS-PAGE and cross-reacted with the appropriate antibody on Western blot (not shown). CAL-free recombinant HMGB1 and HMGB2 proteins were further analyzed for DNA binding activity by EMSA, and examined for cytokine mRNA induction (IL-1α, IL-1β, TNFα, HMGB1, and HMGB2) by real-time PCR. RAW-C3 cells were cultured for 6 d in the presence of RANKL (100 ng/ml), and then TRAP-positive osteoclasts were counted (4,5). Bone marrow cells from TNFα+/+ and TNFα−/− mice were cultured for 6 d in the presence of RANKL (60 ng/ml) and MCSF (30 ng/ml) to stimulate osteoclast formation.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using Student's unpaired t test, with data presented as the mean ± sem. Significance was assumed at P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. S. Masur for her technical assistance with the immunostaining of HMGB.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant AR 052258 to E.A., and by the National Center for Research Resources CA88325, RR017802, and RR022415 to R.W.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no disclosures.

First Published Online January 24, 2008

Abbreviations: AP-1, Activator protein-1; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; CRE, cAMP-responsive element; HMG, high-mobility group; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MCSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; NF, nuclear factor; PMA, phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end products; RANKL, receptor activator for NF-κB ligand; RRS, RANKL-responsive sequence; rNT, ribonucleotide; siRNA, small interfering RNA; TH, thyroid hormone; TR, thyroid receptor; TRAP, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase; TSHR, TSH receptor.

References

- Murphy E, Williams GR 2004 The thyroid and the skeleton. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 61:285–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy GR, Shapiro JL, Bandelin JG, Canalis EM, Raisz LG 1976 Direct stimulation of bone resorption by thyroid hormones. J Clin Invest 58:529–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto JM, Fenton AJ, Holloway WR, Nicholson GC 1994 Osteoblasts mediate thyroid hormone stimulation of osteoclastic bone resorption. Endocrinology 134:169–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe E, Marians RC, Yu W, Wu XB, Ando T, Li Y, Iqbal J, Eldeiry L, Rajendren G, Blair HC, Davies TF, Zaidi M 2003 TSH is a negative regulator of skeletal remodeling. Cell 115:151–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hase N, Ando T, Eldeiry L, Brebene A, Peng Y, Lin Y, Amano H, Davies TF, Sun L, Zaidi M, Abe E 2006 TNFα mediates the skeletal effects of TSH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:12849–12854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett JH, Williams GR 2003 The molecular actions of thyroid hormone in bone. Trends Endocrinol Metab 14:356–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett JH, O'Shea PJ, Sriskantharajah S, Rabier B, Boyde A, Howell PG, Weiss RE, Roux JP, Malaval L, Clement-Lacroix P, Samarut J, Chassande O, Williams GR 2007 Thyroid hormone excess rather than thyrotropin deficiency induces osteoporosis in hyperthyroidism. Mol Endocrinol 21:1095–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett JH, Nordstrom K, Boyde A, Howell PG, Kelly S, Vennstrom B, Williams GR 2007 Thyroid status during skeletal development determines adult bone structure and mineralization. Mol Endocrinol 21:1893–1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann M, Brennan FM, Foxwell BM, Taylor PC, Williams RO, Maini RN 2005 Anti-TNF therapy: where have we got to in 2005? J Autoimmun 25(Suppl):26–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanes MS 2003 Tumor necrosis factor-α: molecular and cellular mechanisms in skeletal pathology. Gene 321:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Imai Y, Matsumoto T, Sato S, Takeuchi K, Igarashi K, Harada Y, Azuma Y, Krust A, Yamamoto Y, Nishina H, Takeda S, Takayanagi H, Metzger D, Kanno J, Takaoka K, Martin TJ, Chambon P, Kato S 2007 Estrogen prevents bone loss via estrogen receptor α and induction of Fas ligand in osteoclasts. Cell 130:811–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenci S, Weitzmann MN, Roggia C, Namba N, Novack D, Woodring J, Pacifici R 2000 Estrogen deficiency induces bone loss by enhancing T-cell production of TNF-α. J Clin Invest 106:1229–1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzmann MN, Pacifici R 2005 The role of T lymphocytes in bone metabolism. Immunol Rev 208:154–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzmann MN, Pacifici R 2006 Estrogen deficiency and bone loss: an inflammatory tale. J Clin Invest 116:1186–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal J, Sun L, Kumar TR, Blair HC, Zaidi M 2006 Follicle-stimulating hormone stimulates TNF production from immune cells to enhance osteoblast and osteoclast formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:14925–14930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Peng Y, Sharrow AC, Iqbal J, Zhang Z, Papachristou DJ, Zaidi S, Zhu LL, Yaroslavskiy BB, Zhou H, Zallone A, Sairam MR, Kumar TR, Bo W, Braun J, Cardoso-Landa L, Schaffler MB, Moonga BS, Blair HC, Zaidi M 2006 FSH directly regulates bone mass. Cell 125:247–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Schwarz EM 2003 The TNF-α transgenic mouse model of inflammatory arthritis. Springer Semin Immunopathol 25:19–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z, Li P, Zhang Q, Schwarz EM, Keng P, Arbini A, Boyce BF, Xing L 2006 TNF increases circulating osteoclast precursor numbers by promoting their proliferation and differentiation in the bone marrow through up-regulation of c-Fms expression. J Biol Chem 281:11846–11855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Fenton MJ, Amar S 2003 Identification and functional characterization of a novel binding site on TNF-α promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:4096–4101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakhov AN, Collart MA, Vassalli P, Nedospasov SA, Jongeneel CV 1990 κB-type enhancers are involved in lipopolysaccharide-mediated transcriptional activation of the tumor necrosis factor α gene in primary macrophages. J Exp Med 171:35–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades KL, Golub SH, Economou JS 1992 The regulation of the human tumor necrosis factor α promoter region in macrophage, T cell, and B cell lines. J Biol Chem 267:22102–22107 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagariya A, Mungre S, Lovis R, Birrer M, Ness S, Thimmapaya B, Pope R 1998 Tumor necrosis factor α gene regulation: enhancement of C/EBPβ-induced activation by c-Jun. Mol Cell Biol 18:2815–2824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxwell B, Browne K, Bondeson J, Clarke C, de Martin R, Brennan F, Feldmann M 1998 Efficient adenoviral infection with IκBα reveals that macrophage tumor necrosis factor α production in rheumatoid arthritis is NF-κB dependent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:8211–8215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaldi T, Langst G, Strohner R, Becker PB, Bianchi ME 2002 The DNA chaperone HMGB1 facilitates ACE/CHRAC-dependent nucleosome sliding. EMBO J 21:6865–6873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller S, Ronfani L, Bianchi ME 2004 Regulated expression and subcellular localization of HMGB1, a chromatin protein with a cytokine function. J Intern Med 255:332–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J, Dixon GH 1990 High mobility group proteins 1 and 2 function as general class II transcription. Am Chem Soc 29:6295–6302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaldi T, Talamo F, Scaffidi P, Ferrera D, Porto A, Bachi A, Rubartelli A, Agresti A, Bianchi ME 2003 Monocytic cells hyperacetylate chromatin protein HMGB1 to redirect it towards secretion. EMBO J 22:5551–5560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME 2002 Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature 418:191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calogero S, Grassi F, Aguzzi A, Voigtlander T, Ferrier P, Ferrari S, Bianchi ME 1999 The lack of chromosomal protein Hmg1 does not disrupt cell growth but causes lethal hypoglycaemia in newborn mice. Nat Genet 22:276–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi N, Yoshida K, Ito T, Tsuda M, Mishima Y, Furumatsu T, Ronfani L, Abeyama K, Kawahara K, Komiya S, Maruyama I, Lotz M, Bianchi ME, Asahara H 2007 Stage-specific secretion of HMGB1 in cartilage regulates endochondral ossification. Mol Cell Biol 27:5650–5663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronfani L, Ferraguti M, Croci L, Ovitt CE, Scholer HR, Consalez GG, Bianchi ME 2001 Reduced fertility and spermatogenesis defects in mice lacking chromosomal protein HMGB2. Development 128:1265–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alappat SR, Zhang M, Zhao X, Alliegro MA, Alliegro MC, Burdsal CA 2003 Mouse pigpen encodes a nuclear protein whose expression is developmentally regulated during craniofacial morphogenesis. Dev Dyn 228:59–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson U, Wang H, Palmblad K, Aveberger AC, Bloom O, Erlandsson-Harris H, Janson A, Kokkola R, Zhang M, Yang H, Tracey KJ 2000 High mobility group 1 protein (HMG-1) stimulates proinflammatory cytokine synthesis in human monocytes. J Exp Med 192:565–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunden-Cullberg J, Norrby-Teglund A, Rouhiainen A, Rauvala H, Herman G, Tracey KJ, Lee ML, Andersson J, Tokics L, Treutiger CJ 2005 Persistent elevation of high mobility group box-1 protein (HMGB1) in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med 33:564–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi A, Blood DC, del Toro G, Canet A, Lee DC, Qu W, Tanji N, Lu Y, Lalla E, Fu C, Hofmann MA, Kislinger T, Ingram M, Lu A, Tanaka H, Hori O, Ogawa S, Stern DM, Schmidt AM 2000 Blockade of RAGE-amphoterin signaling suppresses tumor growth and metastases. Nature 405:354–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Ochani M, Li J, Qiang X, Tanovic M, Harris HE, Susarla SM, Ulloa L, Wang H, DiRaimo R, Czura CJ, Wang H, Roth J, Warren HS, Fink MP, Fenton M J, Andersson U, Tracey KJ 2004 Reversing established sepsis with antagonists of endogenous high-mobility group box 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:296–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotze MT, Tracey K 2005 High-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGN1): nuclear weapon in the immune arsenal. Nat Rev 5:331–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkola R, Sundberg E, Ulfgren AK, Palmblad K, Li J, Wang H, Ulloa L, Yang H, Yan XJ, Furie R, Chiorazzi N, Tracey KJ, Andersson U, Harris HE 2002 High mobility group box chromosomal protein 1: a novel proinflammatory mediator in synovitis. Arthritis Rheum 46:2598–2603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkola R, Li J, Sundberg E, Aveberger AC, Palmblad K, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Andersson U, Harris HE 2003 Successful treatment of collagen-induced arthritis in mice and rats by targeting extracellular high mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 activity. Arthritis Rheum 48:2052–2058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, Vishnubhakat JM, Ombrellino M, Che J, Frazier A, Yang H, Ivanova S, Borovikova L, Manogue KR, Faist E, Abraham E, Andersson J, Andersson U, Molina PE, Abumrad NN, Sama A, Tracey KJ 1999 HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science 285:248–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavart P, Kalousek I, Jandova D, Hrkal Z 1995 Differential expression of nuclear HMG1 and HMG2 proteins and H10 histone in various blood cells. Cell Biochem Funct 13:125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agresti A, Bianchi ME 2003 HMGB proteins and gene expression. Curr Opin Genet Dev 13:170–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abate C, Baker SJ, Lees-Miller SP, Anderson CW, Marshak DR, Curran T 1993 Dimerization and DNA binding alter phosphorylation of Fos and Jun. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:6766–6770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonyaratanakornkit V, Melvin V, Prendergast P, Altmann M, Ronfani L, Bianchi ME, Taraseviciene L, Nordeen SK, Allegretto EA, Edwards DP 1998 High-mobility group chromatin proteins 1 and 2 functionally interact with steroid hormone receptors to enhance their DNA binding in vitro and transcriptional activity in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol 18:4471–4487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayed H, Izsvak Z, Khare D, Heinemann U, Ivics Z 2003 The DNA-bending protein HMGB1 is a cellular cofactor of sleeping beauty transposition. Nucleic Acid Res 31:2313–2322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkola R, Andersson A, Mullins G, Ostberg T, Treutiger CJ, Arnold B, Nawroth P, Andersson U, Harris RA, Harris HE 2005 RAGE is the major receptor for the proinflammatory activity of HMGB1 in rodent macrophages. Scan J Immunol 61:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann MA, Drury S, Fu C, Qu W, Taguchi A, Lu Y, Avila C, Kambham N, Bierhaus A, Nawroth P, Neurath MF, Slattery T, Beach D, McClary J, Nagashima M, Morser J, Stern D, Schmidt AM 1999 RAGE mediates a novel proinflammatory axis: a central cell surface receptor for S100/calgranulin polypeptides. Cell 97:889–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucciarelli LG, Kaneko M, Ananthakrishnan R, Harja E, Lee LK, Hwang YC, Lerner S, Bakr S, Li Q, Lu Y, Song F, Qu W, Gomez T, Zou YS, Yan SF, Schmidt AM, Ramasamy R 2006 Receptor for advanced-glycation end products: key modulator of myocardial ischemic injury. Circulation 113:1226–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucciarelli LG, Wendt T, Qu W, Lu Y, Lalla E, Rong LL, Goova MT, Moser, Kislinger T, Lee DC, Kashyap Y, Stern DM, Schmidt AM 2002 RAGE blockade stabilizes established atherosclerosis in diabetic apolipoprotein E-null mice. Circulation 106:2827–2835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BI, Wendt T, Bucciarelli LG, Rong LL, Naka Y, Yan SF, Schmidt AM 2005 Diabetic vascular disease: it's all the RAGE. Antioxid Redox Signal 7:1588–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong LL, Yan SF, Wendt T, Hans D, Pachydaki S, Bucciarelli LG, Adebayo A, Qu W, Lu Y, Kostov K, Lalla E, Yan SD, Gooch C, Szabolcs, Trojaborg W, Hays AP, Schmidt AM 2004 RAGE modulates peripheral nerve regeneration via recruitment of both inflammatory and axonal outgrowth pathways. FASEB J 18:1818–1825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlova VV, Choi EY, Xie C, Chavakis E, Bierhaus A, Ihanus E, Ballantyne CM, Gahmberg CG, Bianchi M, Nawroth PP, Chavakis T 2007 A novel pathway of HMGB1-mediated inflammatory cell recruitment that requires Mac-1-integrin. EMBO J 26:1129–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding KH, Wang ZZ, Hamrick MW, Deng ZB, Zhou L, Kang B, Yan SL, She JX, Stern DM, Isales CM, Mi QS 2006 Disordered osteoclast formation in RAGE-deficient mouse establishes an essential role for RAGE in diabetes related bone loss. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 340:1091–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Immel D, Xi CX, Bierhaus A, Feng X, Mei L, Nawroth P, Stern DM, Xiong WC 2006 Regulation of osteoclast function and bone mass by RAGE. J Exp Med 203:1067–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimi E, Aoki K, Saito H, D'Acquisto F, May MJ, Nakamura I, Sudo T, Kojima T, Okamoto F, Fukushima H, Okabe K, Ohya K, Ghosh S 2004 Selective inhibition of NF-κB blocks osteoclastogenesis and prevents inflammatory bone destruction in vivo. Nat Med 10:617–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampath TK, Simic P, Sendak R, Draca N, Bowe AE, O'Brien S, Schiavi SC, McPherson JM, Vukicevic S 2007 Thyroid-stimulating hormone restores bone volume, microarchitecture, and strength in aged ovariectomized rats. J Bone Miner Res 22:849–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marians RC, Ng L, Blair HC, Unger P, Graves PN, Davies TF 2005 Defining TSH-dependent and TSH-independent steps of thyroid hormone synthesis using thyrotropin receptor-null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:15776–15781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe FG, Valentine JE, Sewell WA 1997 Cycloporin A and FK506 reduce interleukin-5 mRNA abundance by inhibiting gene transcription. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 17:243–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar A, Chung H, Dolios G, Wang R, Asamoah N, Lobel P, Maxfield FR 10 January 2007 Degradation of fibrillar forms of Alzheimer's amyloid β-peptide by macrophage. J Neurobiol Aging 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging. 2006.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moron JA, Abul-Husn NS, Rozenfeld R, Dolios G, Wang, Devi LA 2007 Morphine administration alters the profile of hippocampal postsynaptic density-associated proteins: a proteomics study focusing on endocytic proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics 6:29–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]