Abstract

Chromosomal translocations induced by ionizing radiation and radiomimetic drugs are thought to arise by incorrect joining of DNA double-strand breaks. To dissect such misrepair events at a molecular level, large-scale, bleomycin-induced rearrangements in the aprt gene of Chinese hamster ovary D422 cells were mapped, the breakpoints were sequenced, and the original non-aprt parental sequences involved in each rearrangement were recovered from nonmutant cells. Of seven rearrangements characterized, six were reciprocal exchanges between aprt and unrelated sequences. Consistent with a mechanism involving joining of exchanged double-strand break ends, there was, in most cases, no homology between the two parental sequences, no overlap in sequences retained at the two newly formed junctions, and little or no loss of parental sequences (usually ≤2 bp) at the breakpoints. The breakpoints were strongly correlated (P < 0.0001) with expected sites of bleomycin-induced, double-strand breaks. Fluorescence in situ hybridization indicated that, in six of the mutants, the rearrangement was accompanied by a chromosomal translocation at the aprt locus, because upstream and downstream flanking sequences were detected on separate chromosomes. The results suggest that repair of free radical-mediated, double-strand breaks in confluence-arrested cells is effected by a conservative, homology-independent, end-joining pathway that does not involve single-strand intermediate and that misjoining of exchanged ends by this pathway can directly result in chromosomal translocations.

Keywords: bleomycin, nonhomologous recombination, DNA repair, DNA end-joining, gene rearrangements

Among the chromosomal alterations induced by ionizing radiation (1) and radiomimetic drugs (2, 3) are reciprocal translocations between nonhomologous chromosomes. Although these and other genomic rearrangements for many years have been commonly ascribed to incorrect rejoining of the DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) induced by these agents (3–5), the molecular details of this process have remained obscure.

For analyzing the processing of free radical-mediated DSBs in vivo, radiomimetic drugs offer the distinct advantage of inducing a limited spectrum of chemically defined, sequence-specific DNA lesions, involving oxidative damage that is largely restricted to the sugar moiety (5, 6). As shown below, the rearrangements induced by bleomycin in the aprt gene of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) D422 cells almost exclusively are reciprocal exchanges between unrelated sequences on different chromosomes. The sequences of the newly formed junctions are consistent with a mechanism involving highly conservative end-joining of exchanged DSB ends. In some cases, it has been possible to infer, at single-nucleotide resolution, how these ends must have been processed to produce the observed breakpoint junctions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines with rearranged aprt genes were from a mutant collection generated previously by treatment of confluence-arrested CHO-D422 cells (hemizygous for aprt) for 2 days with low concentrations of bleomycin (7).

After PCR-based mapping (8), the rearrangement breakpoints were amplified by nested ligation-mediated PCR, using pUC19 as an anchor (9). Mutant genomic DNA was cleaved with MboI or Tsp509I, and then 0.5 μg was ligated to 2 μg of BamHI- or EcoRI-cut dephosphorylated pUC19 DNA. The ligated DNA was subjected to 25 cycles of PCR (1 min at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C), using 0.5 μg each of an outer nested aprt primer and the outer nested pUC19 primer (TGTGCTGCAAGGCGATTAAG). A 5-μl aliquot of this reaction mixture then was used as the template for a second PCR with inner nested aprt and pUC19 (TTTCCCAGTCACGACGTTGT) primers. A third inner nested aprt primer then was used to sequence the resulting product across the breakpoint, using an Epicentre Technologies (Madison, WI) cycle sequencing kit. (A complete list of the more than 40 genomic primers used is available from the authors on request.)

To determine whether the two sequences that had become linked to aprt in each mutant were themselves linked in nonmutant cells (as in a reciprocal exchange), PCR was performed using DNA from the CHO-D422 parent line and a primer from each of the two non-aprt genomic sequences, with the primers directed toward each junction with aprt. The products were sized on low melting point agarose gels, in some cases isolated as single bands, and sequenced using one of the PCR primers or an internal primer.

For fluorescence in situ hybridization, metaphase spreads from the cell lines were prepared and GTG-banded by standard procedures (10). The λDM2 and λB21 probes (kindly provided by Mark Meuth) (11) were labeled directly with the fluorophores Spectrum Green and Spectrum Orange (Vysis, Downers Grove, IL), respectively, using a nick-translation kit (Vysis). A mixture consisting of 500 ng of each labeled probe, plus 10 μg of repetitive C0t-1 DNA (12) from CHO-D422 cells to suppress nonspecific hybridization, was precipitated, resuspended in hybridization buffer (Vysis), denatured at 70°C for 5 min, and suppression-hybridized for 1 h at 37°C. In situ hybridization was performed as described (10), except that the slides first were denatured at 70°C for 70 s and then hybridized with the probes at 37°C for 16 h. At least 20 metaphases were analyzed per cell line.

RESULTS

Bleomycin-Induced Rearrangements Are Illegitimate Reciprocal Exchanges.

As reported previously (7), bleomycin-induced mutagenesis at the aprt locus, although barely detectable in exponentially growing CHO-D422 cells, was quite robust in confluence-arrested cells. About 10% of the resulting mutations were large scale rearrangements. PCR-based mapping indicated that, in each of these rearrangements, most if not all of the aprt sequence was retained, but there was a small segment of the gene across which no PCR products could be generated. These results were inconsistent with a simple deletion and instead suggested a discontinuity in gene structure, either a large insertion or the translocation of the two halves of aprt to distant genomic sites. Ligation-mediated PCR was used to walk from known aprt sequences into the rearrangement; usually 100–200 bp of non-aprt sequence beyond each breakpoint was determined. In every case, the aprt sequence stopped abruptly and was linked to a sequence having no homology to aprt (Fig. 1). The upstream and downstream aprt breakpoints were invariably within 2 bp of each other, and in no case was even a single bp of aprt sequence unambiguously duplicated at the two junctions.

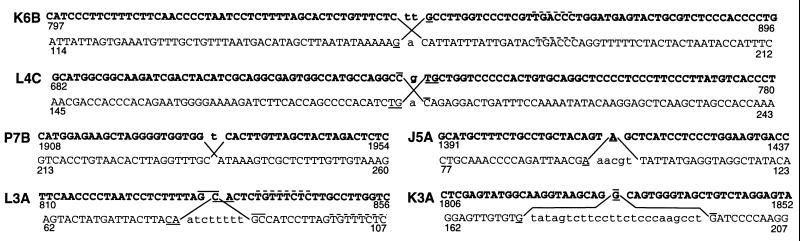

Figure 1.

Lack of homology between aprt (bold) and non-aprt parental sequences (GenBank accession nos. U94480–U94486) at sites of reciprocal exchanges. Diagonal lines show the reciprocal exchange, with bases that were unequivocally deleted shown in lower case. Bases that were present in both parental sequences but that occur only once at the newly formed junction are shown by overlines (upstream aprt breakpoint) and underlines (downstream breakpoint), e.g., the junction sequences in L3A are -TTTAGCCATC- and -CTTACACTCT-. Except for the 8-bp homology in L3A (dashed lines), the longest homologies anywhere within 50-bp regions flanking the breakpoints were 6 bp, and these occurred with the frequency expected for random unrelated sequences. aprt numbering is according to Phear et al. (13).

To determine whether these rearrangements were reciprocal exchanges, PCR was performed using DNA from parental D422 cells and a primer from each of the two sequences to which aprt had been linked. For six of the seven mutants, a PCR product was obtained, with a length approximately equal to the sum of the distances from each primer site to the breakpoint. Sequencing of these products confirmed that they corresponded to the non-aprt sequences involved in the rearrangement; thus, all but one of the rearrangements were reciprocal exchanges between aprt and some unrelated sequence (Fig. 1). The rearrangements involved minimal loss and no duplication of the non-aprt parental sequences although small (5–24 bp) deletions at the breakpoint were more common for the non-aprt than for the aprt parent. Some of the junctions occurred at 1- or 2-bp overlaps common to both parental sequences, but these were no more frequent than would be expected for sequences joined at random. A GenBank search revealed that none of the non-aprt parental sequences had been reported previously, but several showed significant homologies, one (L3A) to a viral env gene, one (L4C) to the rodent L1 long repeat family, and one (K3A) to another rodent middle repetitive element.

Rearrangement Breakpoints Correlate with Potential DSB Sites.

In vitro studies have shown that bleomycin-induced DSBs are sequence-specific, with the primary break consistently occurring at a GC or GT sequence, and the secondary break in the complementary strand nearly always occurring either directly opposite or on a one-base 5′ stagger; the choice of these two secondary cleavage sites can be predicted by a set of sequence-dependent selection rules (14–16). These breaks have 5′-phosphate and 3′-phosphoglycolate termini and involve loss of a single base from each strand (5).

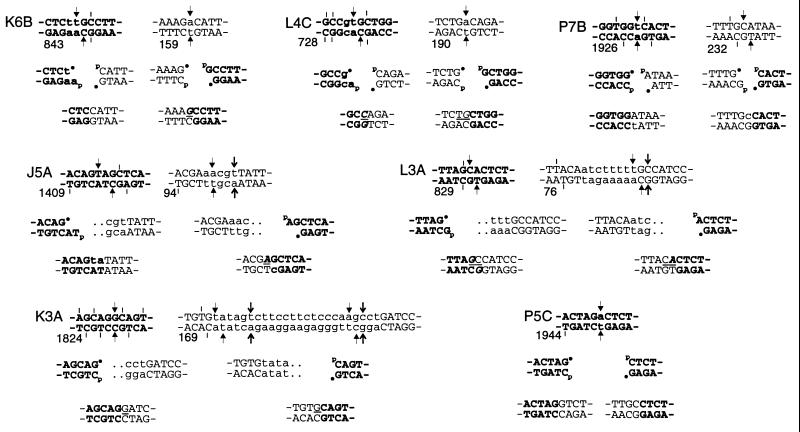

As shown in Fig. 2, one or more potential sites of bleomycin-induced double-strand cleavage (GC or GT) were found between the upstream and downstream breakpoints of each of the two parental sequences involved in each of the bleomycin-induced rearrangements; thus, joining of the exchanged ends of the two breaks could account for each of the exchanges. For three of the mutants (K6B, L4C, and P7B), the putative breaks in both of the parental sequences were determined uniquely. Thus, it was possible to infer, at single-nucleotide resolution, how the termini of these breaks must have been processed during end-joining. In most cases, such processing appeared to be minimal, i.e., the removal of at most 1–2 bases (or bp) from the ends and/or the fill-in of 5′-overhangs, before religation. Sequences surrounding the five uniquely determined sites of putative blunt-end cleavage (non-aprt parental sequences in K6B and L4C; aprt sequences in P7B, K3A, and P5C) appeared to be particularly well conserved; not a single base pair of flanking DNA sequence was unambiguously lost even though the target bp was unambiguously deleted in four of five cases (as expected because both the GPy nucleotide and its complement would be fragmented in formation of the break). For the exchanges with slightly larger deletions, in which the DSB site was not always uniquely determined, more extensive trimming of at least one of the DSB ends would have to be invoked, but otherwise the same homology-independent joining processes appeared to prevail. In no case was there evidence of any complex strand-exchange schemes or nontemplated sequence additions, and only in mutant L3A could a microhomology of more than a single base pair in the two ends be invoked to account for sequence alignment at the junction.

Figure 2.

Putative DSB intermediates and joining mechanisms for bleomycin-induced reciprocal exchanges. The top line shows aprt (bold) and non-aprt parental sequences. Numbering below the sequences refers to the leftmost base pair shown. Arrows show potential DSB sites that could have initiated the exchanges, and short vertical lines show sites that could not; different arrow styles serve to distinguish between individual, closely spaced sites. Lowercase letters show bases that were deleted unambiguously in the rearrangement. In cases in which there was only one cleavage site in the parental sequence consistent with the resulting rearrangement, the second line shows putative exchanged break ends whose joining led to the rearrangements. 3′-phosphoglycolate ends are indicated by •, and 5′-phosphates are indicated by p. Dotted lines indicate cases in which the cleavage site was not uniquely determined. The bottom line shows the junctions. Here, lowercase letters indicate bases that would have to have been added by fill-in of 5′ overhangs, and italics indicate bases that could have come from either break end, assuming the cleavages occurred as shown. Underlines between the strands show base pairs that could have originated from either parental sequence, if no assumptions are made with regard to cleavage sites. The putative cleavage site in the aprt parental sequence of J5A is a two-base-staggered cut; such cuts are rare but do occur at sequences of the form GPyNPuC•GPyNPuC (15), of which there are 33 in the aprt gene. Mutant P5C was presumably not a reciprocal exchange; primers from the two non-aprt sequences did not generate any PCR product from template DNA of nonmutant cells.

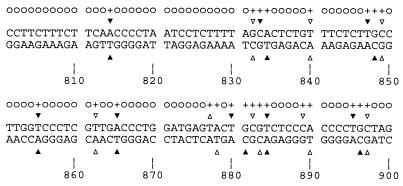

To assess the statistical significance of the apparent correlation between rearrangement breakpoints and potential bleomycin cleavage sites, the entire genomic aprt sequence between the start and stop codons (1913 bp) was analyzed in terms of whether a reciprocal exchange, involving loss of a given number of base pairs and occurring at each possible position in that sequence, would contain a potential cleavage site between the upstream and downstream aprt breakpoints. This analysis (Fig. 3) revealed that, for example, in the case of reciprocal exchanges involving loss of 1 bp, the probability that a randomly positioned breakpoint would correspond to a bleomycin cleavage site is 673/1913 = 0.352. Table 1 lists the comparable probabilities for the six bleomycin-induced reciprocal exchanges for which both parental sequences are known, along with the corresponding probabilities calculated from similar analysis of the known portion of each non-aprt parental sequence. These data show that, although there is a fairly high probability that any given breakpoint will correspond to a bleomycin cleavage site, the cumulative probability that both breakpoints of all six translocations will have this specificity is negligible (<0.0001). Moreover, in nine similar reciprocal exchanges induced by neocarzinostatin, which induces DSBs with a different sequence specificity (6), only 6 of the 15 parental sequences from which <5 bp had been lost contained a potential site for bleomycin-induced cleavage between the two breakpoints (unpublished results). Thus, it appears that the correlation between bleomycin cleavage sites and rearrangement breakpoints is both significant and specific, supporting the proposal that the exchanges arose by exchange of the ends of drug-induced DSBs.

Figure 3.

Analysis of base pairs 801–900 of the aprt coding sequence (encompassing rearrangements K6B and L3A) in terms of potential cleavage sites and rearrangement breakpoints. Triangles show potential DSB sites; solid vs. open triangles serve to distinguish closely spaced sites. Each GPy sequence was considered a potential primary site, and the corresponding secondary site in the complementary strand was assigned as described (15). A “+” or “o” above a particular base pair indicates that a rearrangement with a breakpoint at that nucleotide position, involving only deletion of that single base pair, either would (+) or would not (o) be consistent with the translocation having been initiated by a bleomycin-induced DSB, assuming that there were no nontemplated additions to the break termini. For example, a rearrangement involving loss of only the G⋅C bp at position 833 would be consistent with initiation by a staggered DSB at base pairs 833–834, followed by removal of the resulting “G” overhang on the upstream side of the break and fill-in of the “A” overhang on the downstream side. However, a rearrangement in which only the A⋅T base pair at position 831 was deleted would be inconsistent with initiation by a drug-induced DSB because the blunt-ended break at position 832 would eliminate base pair 832 completely, thus precluding retention of the G in the GCAC sequence on the downstream side of the breakpoint. Continuation of this analysis for the entire aprt coding sequence revealed that translocations involving loss of a single base pair at 673 (35.2%) of the 1913 possible positions in aprt would be consistent with the translocation having originated with a bleomycin-induced DSB. The analysis was repeated for translocations having various numbers of base pairs deleted at the breakpoint.

Table 1.

Cytogenetic characterization of rearrangement mutants and probabilities of translocation breakpoints occurring at potential bleomycin cleavage sites

| Mutant | Chromosomes, n

|

Bases deleted*

|

P value†

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total‡ | Altered§ | aprt | Non-aprt | aprt | Non-aprt¶ | Both‖ | |

| K6B | 21 | 4–7 | 3 | 2 | 0.598 | 0.323 | 0.193 |

| L4C | 21 | 6–7 | 4 | 4 | 0.694 | 0.613 | 0.425 |

| P7B | 21 | 5–8 | 1 | 0 | 0.352 | 0.118 | 0.0415 |

| J5A | 21 | 5–8 | 0 | 6 | 0.153 | 0.800 | 0.122 |

| L3A | 20 | 2–5 | 3 | 12 | 0.598 | 0.929 | 0.556 |

| K3A | 18 | 2–3 | 1 | 26 | 0.352 | 1.000 | 0.352 |

| P5C | 21 | 3–4 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Cumulative‖ | 0.000081 | ||||||

Number of base pairs lost from each parental sequence, as determined from the sequences of the junctions. To obtain the most conservative estimate of statistical significance, bases that could have originated from either sequence (underlines in Figs. 1 and 2) were considered to have been lost from both sequences. Thus, P is actually an upper limit of the probability in those cases.

Probability that a randomly positioned translocation involving deletion of the prescribed number of bases from the sequence in question would correspond to a bleomycin-induced DSB site; determined as described in Fig. 3.

Modal number. The modal number for the parental D422 line was 20.

As compared with D422; there was heterogeneity in the number of rearranged chromosomes seen in individual metaphase spreads of each mutant line.

Probability values for the non-aprt parental sequences were obtained by analyzing the entire known segment of each such sequence (ranging from 145 to 412 bp) as in Fig. 3. Although the limits set on the “target sequence” are thus arbitrary, P values for each deletion size tended to be similar for all sequences examined.

Assuming that the locations of the two breakpoints were independent of each other, the probability that both will correspond to bleomycin cleavage sites is the product of the probabilities for each breakpoint. The probability that all 12 breakpoints will correspond to cleavage sites is the cumulative product of all the individual probabilities.

Most Reciprocal Exchanges Result in Chromosomal Translocations at or near the aprt Locus.

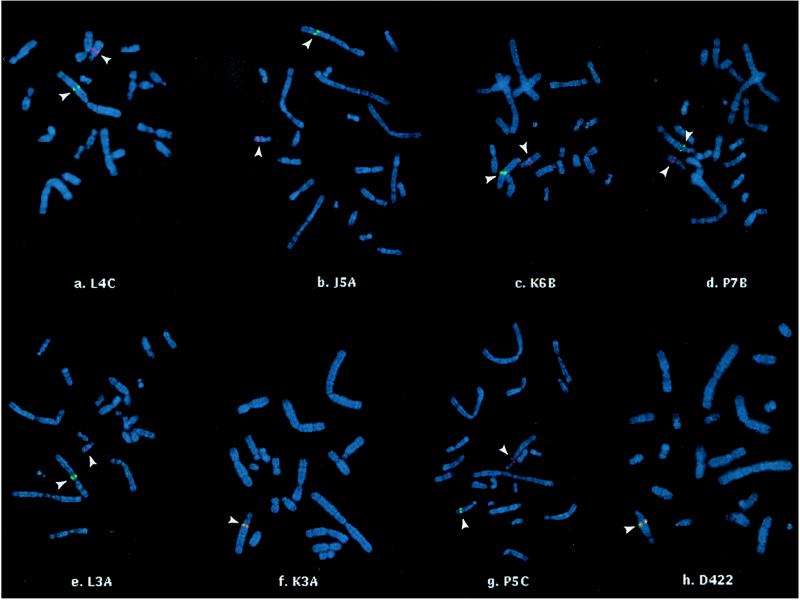

To determine whether the reciprocal exchanges were inter- or intra-chromosomal, metaphase spreads of each mutant cell line were hybridized with probes corresponding to sequences 50 kb upstream (λDM2, green fluorescence) and 10 kb downstream (λB21, red fluorescence) from aprt (11) (Fig. 4). The parental CHO-D422 strain had a chromosomal complement and GTG-banding pattern typical of CHO cells (17, 18). A single overlapping (yellow) hybridization signal corresponding to the hemizygous aprt locus was detected at the expected position in the proximal long arm of CHO chromosome Z4 (Fig. 4h), which is a pericentric inversion of the normal Chinese hamster chromosome 3. The mutant lines, however, all showed rearrangements in two or more chromosomes, as indicated by alterations in GTG-banding patterns (Table 1). In six of the seven mutant lines, the DM2 and B21 sequences no longer were juxtaposed on the Z4 chromosome but were located on separate chromosomes (Fig. 4). For five of these six mutants (L4C, J5A, K6B, P7B, and L3A), the red signal (B21) was localized to an acrocentric chromosome that was smaller than the Z4 chromosome (a probable Z4 derivative). The green signals (DM2) were found on marker chromosomes having different morphologies from one another and from chromosomes seen in the parental D422 line. In the mutant line P5C, the red signal was present on an acrocentric chromosome that was comparable in size to the Z4 chromosome, with the green signal (DM2) hybridizing to a small acrocentric chromosome. Also, in one mutant line (K3A), the signals remained contiguous to one another, apparently being retained on the Z4 chromosome. This result is consistent with a small inversion resulting from an intrachromosomal reciprocal exchange between two nearby DSBs in Z4.

Figure 4.

In situ hybridization of sequences upstream and downstream of aprt. The parental D422 strain (h.) shows the expected single overlapping (red + green = yellow) signal in the long arm of the Z4 chromosome (identified by GTG banding; not shown). All of the mutants except K3A show separation of signals corresponding to the upstream (green) and downstream (red) flanking sequences (arrowheads), implying a translocation at the aprt locus. In h, the Z4 centromere is at the upper end of the chromosome.

The results for the six mutants having separated flanking sequences are most easily explained by a model in which the aprt and non-aprt sequences involved in the rearrangement were on different chromosomes, and thus the exchange of broken DNA ends resulted in a reciprocal (or, in the case of P5C, nonreciprocal) chromosomal translocation. The fact that only the downstream (B21) flanking sequence was found consistently on an apparent Z4 derivative suggests that the direction of aprt transcription on Z4 is toward the centromere. Although it is conceivable that the aprt rearrangement and the chromosomal translocation were independent events, the separation of DM2 and B21 sequences appeared to be specifically associated with aprt rearrangements because (i) of nine cell lines derived from the same mutant collection but having only point mutations in aprt, eight had coincident DM2 and B21 signals on chromosome Z4 or a derivative thereof, and only one showed separation of the two signals (data not shown); and (ii) at least five of nine aprt rearrangement mutants induced by neocarzinostatin also showed separation of the B21 and DM2 signals (unpublished results). Nevertheless, the differences in GTG banding between D422 and the mutants could not be explained by a single reciprocal translocation at the aprt locus, implying that additional chromosome rearrangements had occurred (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

There is an emerging consensus that, in mammalian cells, most DSBs probably are repaired by end-joining rather than by homologous recombination (5, 19, 20). Whereas, at least in theory, repair by homologous recombination should be error-free, repair by end-joining raises the possibility of two types of errors. Small deletions or insertions could result from end-processing (such as removal of fragmented nucleotides) before religation (7, 8, 21); large-scale rearrangements could result from joining of the end of one DSB to an end of another DSB occurring at a site well separated in the genome, perhaps even on a different chromosome. Both reciprocal and nonreciprocal translocations induced by ionizing radiation and radiomimetic drugs (as detected at the chromosomal level) long have been ascribed to such breakage and misjoining (1, 3). Yet, few if any such reciprocal exchanges induced by any of these agents have been characterized fully at the DNA sequence level, and thus the molecular details of these putative misjoining events have remained obscure. Indeed, the apparent acquisition of a persistent, global genomic instability in irradiated cells has raised the possibility that many of the rearrangements seen in the progeny of these cells may occur by mechanisms that do not directly involve the processing of radiation-induced DNA breaks (22, 23).

The present data, however, particularly the correspondence between rearrangement breakpoints and expected DSB sites, suggest that reciprocal exchanges between distant genomic sites and between chromosomes can result directly from the joining of exchanged DSB ends. The data also show that the exchanges are surprisingly conservative and that they can occur between sequences that share no homology whatsoever. Neither of these features give any suggestion of single-stranded DNA segments being intermediates in the exchanges; rather, the results are consistent with a mechanism involving direct joining of DSB ends, with minimal processing of the termini before ligation. Although the data do not rigorously eliminate the possibility that the rearrangements were the result of single-strand breaks (which are also induced at GPy sites, and with higher frequency), it seems unlikely given the lack of homology between the parental sequences at the rearrangement junctions. If single-strand exchange and other homology-dependent processes are excluded, it is difficult to devise a mechanism by which single-strand breaks could lead to reciprocal translocations, other than by their conversion to DSBs. Moreover, those DSBs would have to have geometry very similar to that of bleomycin-induced DSBs (breaks either directly opposed or staggered by ≤2 bp) to explain the infrequency of deletions and duplications in the newly formed junctions. Hence, drug-induced DSBs seem a far more likely candidate for the initiating lesions than single-strand breaks. The apparent retention of nearly all terminal sequences at sites of putative blunt-end cleavage is particularly striking and supports the proposal that the high frequency of −1 deletions at potential sites of blunt-ended DSB, seen in the same collection of bleomycin-induced aprt mutants (7), is caused by conservative end-joining of DSBs.

Although nearly all examples of DNA end-joining share certain common features, i.e., the apparent use of “microhomologies” of one to several base pairs for sequence alignment and the frequent loss of terminal sequences from the ends, there is great variability in the size and frequency of both features (21, 24–29). In the putative end-joining events associated with bleomycin-induced reciprocal translocations, deletions were generally restricted to a very few terminal base pairs, and microhomologies, if used at all, were very short (1–2 bp) and likewise restricted to a very few base pairs at the ends or in the overhangs. These specificities are reminiscent of the in vitro joining of noncomplementary DNA ends, bearing either 3′-hydroxyl or 3′-phosphoglycolate termini by Xenopus egg extracts (24, 30). In contrast, in the putative joining of DSBs induced in the CHO aprt gene by restriction enzymes (21) or by cleavage of an integrated I-SceI site (20), the microhomologies used for alignment (usually 2–4 bp) were often a significant distance from the DNA ends, and there were frequently deletions ranging from several base pairs to a few hundred base pairs at the joining site.

One possible explanation for this disparity is that the 3′-phosphoglycolate termini of bleomycin-induced DSBs may protect the ends from exonucleolytic degradation and thus protect internal sequences from the single-strand exposure that is presumably required for microhomology-based joining. If so, however, this protection apparently does not apply to ends of bleomycin-induced DSBs in transfected shuttle vectors, the rejoining of which is associated with larger terminal deletions and more microhomologies at the junctions (31). Moreover, most aprt rearrangements recovered from irradiated, exponentially growing CHO-D422 cells were also complex, nonconservative events (32), similar to rearrangements found in irradiated human cells (33) but quite different from the relatively simple exchanges described here.

A second possibility is that end-joining is more conservative in plateau-phase cells, nearly all other studies of end-joining and gene rearrangements having been performed on exponentially growing cells. DSB repair in mammalian cells is partially defective in cells lacking DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) (19), and this repair deficit is expressed most strongly in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (34). These results raise the possibility that the conservative nature of bleomycin-induced reciprocal translocations may be attributable to the dominance of a DNA-PK-based pathway in repairing DSBs in G1/G0 cells. Consistent with this proposal is the finding that end-joining in the Xenopus system, which most closely resembles the end-joining associated with bleomycin-induced reciprocal translocations, is completely blocked by inhibitors of DNA-PK (30).

All of the aprt rearrangement mutants showed multiple chromosomal alterations, compared with the D422 parent line. Although these alterations (like the aprt rearrangement itself) could have been a direct result of misjoining of bleomycin-induced DSBs, preliminary results suggest that most of the base substitution mutants from the same mutant collection, which were derived from the same bleomycin treatment and selection process, have karyotypes indistinguishable from that of D422. Thus, there appears to be a nonrandom distribution of chromosome alterations among progeny of the treated cell population, suggesting either a nonrandom distribution of initial damage or a global loss of chromosome stability associated with the aprt rearrangement. The variability in chromosome rearrangements within individual mutant lines (Table 1) is reminiscent of the persistent chromosome instability, associated with lowered plating efficiency and an increased spontaneous mutation rate, typically found in a small fraction of the progeny of irradiated CHO cells (22, 23).

Given that a quite significant fraction of DSBs apparently are misjoined, not only in CHO cells but even in normal diploid cells (35), it is likely that there are additional downstream surveillance systems that are able to recognize these aberrant repair events after they occur and channel the offending cell into permanent growth arrest or programmed cell death. One approach to defining the nature of those systems is to determine the genetic requirements for cellular tolerance of specific misrepair events, such as those described herein.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark Meuth for suggesting use of the λ probes and for editorial comments and Richard Moran for a critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by Grants CA40615 and HD33527 from the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Lea D E. Actions of Radiations on Living Cells. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Bull P P W, Goudzwaard J H. Mutat Res. 1980;69:319–324. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(80)90096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vig B K, Lewis R. Mutat Res. 1978;61:309–317. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bender M A, Griggs H G, Bedford J S. Mutat Res. 1974;23:197–212. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(74)90140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Povirk L F. Mutat Res. 1996;355:71–89. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(96)00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dedon P C, Goldberg I H. Chem Res Toxicol. 1992;5:311–332. doi: 10.1021/tx00027a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Povirk L F, Bennett R A O, Wang P, Swerdlow P S, Austin M J F. J Mol Biol. 1994;243:216–226. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang P, Povirk L F. Mutat Res. 1997;373:17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(96)00182-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizobuchi M, Frohman L A. Biotechniques. 1993;15:214–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson-Cook C, Bae V, Edelman W, Brothman A, Ware J. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1997;87:14–23. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(95)00232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis R, Meuth M. Somatic Cell Mol Genet. 1994;20:287–300. doi: 10.1007/BF02254718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landegent J E, in de Wal N J, Dirks R W, Baas F, van der Ploeg M. Hum Genet. 1987;77:366–370. doi: 10.1007/BF00291428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phear G, Armstrong W, Meuth M. J Mol Biol. 1989;209:577–582. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90595-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steighner R J, Povirk L F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8350–8354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Povirk L F, Han Y-H, Steighner R J. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8508–8514. doi: 10.1021/bi00440a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Absalon M J, Kozarich J W, Stubbe J. Biochemistry. 1995;34:2065–2075. doi: 10.1021/bi00006a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adair G M, Nairn R S, Brotherman K A, Siciliano M J. Somatic Cell Mol Genet. 1989;15:535–544. doi: 10.1007/BF01534914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Worton R G, Ho C C, Duff C. Somatic Cell Genet. 1977;3:27–45. doi: 10.1007/BF01550985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson S P, Jeggo P A. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:412–415. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sargent R G, Brenneman M A, Wilson J H. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:267–277. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillips J W, Morgan W F. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5794–5803. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.5794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murnane J P. Mutat Res. 1996;367:11–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgan W F, Day J P, Kaplan M I, McGhee E M, Limoli C L. Radiat Res. 1996;146:247–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfeiffer P, Thode S, Hancke J, Vielmetter W. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:888–895. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meuth M. In: Mobile DNA. Berg D, Howe M, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1989. pp. 833–853. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth D B, Wilson J H. In: Genetic Recombination. Kucherlapati R, Smith G R, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1988. pp. 621–653. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukacsovich T, Yang D, Waldman A S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5649–5657. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.25.5649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rouet P, Smih F, Jasin M. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8096–8106. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roth D B, Wilson J H. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:4295–4304. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.12.4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gu X-Y, Bennett R A O, Povirk L F. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19660–19663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dar M E, Jorgensen T J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3224–3230. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.16.3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breimer L H, Nalbantoglu J, Meuth M. J Mol Biol. 1986;192:669–674. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris T, Thacker J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1392–1396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee S E, Mitchell R A, Cheng A, Hendrickson E A. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1425–1433. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Löbrich M, Rydberg B, Cooper P K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12050–12054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]