Abstract

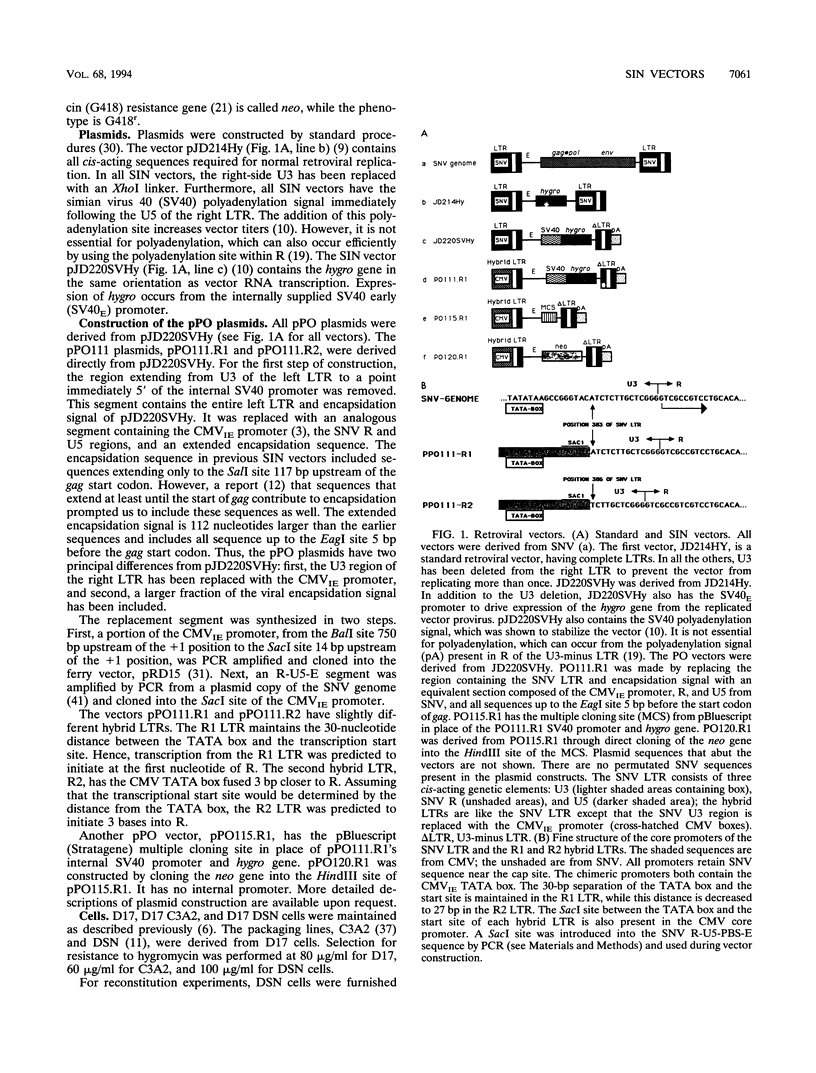

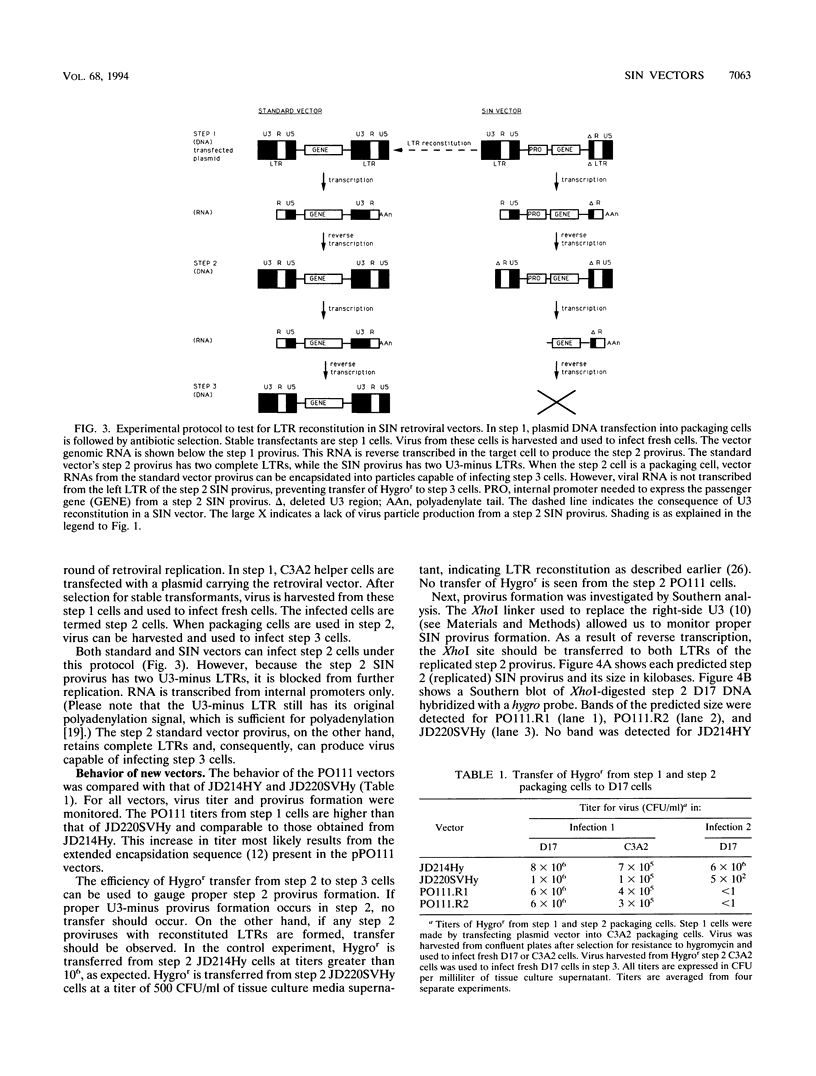

Self-inactivating (SIN) retroviral vectors contain a deletion spanning most of the right long terminal repeat's (LTR's) U3 region. Reverse transcription copies this deletion to both LTRs. As a result, there is no transcription from the 5' LTR, preventing further replication. Many previously developed SIN vectors, however, had reduced titers or were genetically unstable. Earlier, we reported that certain SIN vectors derived from spleen necrosis virus (SNV) experienced reconstitution of the U3-deleted LTR at high frequencies. This reconstitution occurred on the DNA level and appeared to be dependent on defined vector sequences. To study this phenomenon in more detail, we developed an almost completely U3-free retroviral vector. The promoter and enhancer of the left LTR were replaced with those of the cytomegalovirus immediate-early genes. This promoter swap did not impair the level of transcription or alter its start site. Our data indicate that SNV contains a strong initiator which resembles that of human immunodeficiency virus. We show that the vectors replicate with efficiencies similar to those of vectors possessing two wild-type LTRs. U3-deleted vectors carrying the hygromycin B phosphotransferase gene did not observably undergo LTR reconstitution, even when replicated in helper cells containing SNV-LTR sequences. However, vectors carrying the neomycin resistance gene did undergo LTR reconstitution with the use of homologous helper cell LTR sequences as template. This supports our earlier finding that sequences within the neomycin resistance gene can trigger recombination.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson W. F. Prospects for human gene therapy. Science. 1984 Oct 26;226(4673):401–409. doi: 10.1126/science.6093246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop J. M. Cellular oncogenes and retroviruses. Annu Rev Biochem. 1983;52:301–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.001505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boshart M., Weber F., Jahn G., Dorsch-Häsler K., Fleckenstein B., Schaffner W. A very strong enhancer is located upstream of an immediate early gene of human cytomegalovirus. Cell. 1985 Jun;41(2):521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone R. D., Mulligan R. C. High-efficiency gene transfer into mammalian cells: generation of helper-free recombinant retrovirus with broad mammalian host range. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Oct;81(20):6349–6353. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue R. E., Kessler S. W., Bodine D., McDonagh K., Dunbar C., Goodman S., Agricola B., Byrne E., Raffeld M., Moen R. Helper virus induced T cell lymphoma in nonhuman primates after retroviral mediated gene transfer. J Exp Med. 1992 Oct 1;176(4):1125–1135. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.4.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornburg R., Temin H. M. Presence of a retroviral encapsidation sequence in nonretroviral RNA increases the efficiency of formation of cDNA genes. J Virol. 1990 Feb;64(2):886–889. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.886-889.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornburg R., Temin H. M. cDNA genes formed after infection with retroviral vector particles lack the hallmarks of natural processed pseudogenes. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Jan;10(1):68–74. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty J. P., Temin H. M. A promoterless retroviral vector indicates that there are sequences in U3 required for 3' RNA processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Mar;84(5):1197–1201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty J. P., Temin H. M. High mutation rate of a spleen necrosis virus-based retrovirus vector. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Dec;6(12):4387–4395. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.12.4387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty J. P., Wisniewski R., Yang S. L., Rhode B. W., Temin H. M. New retrovirus helper cells with almost no nucleotide sequence homology to retrovirus vectors. J Virol. 1989 Jul;63(7):3209–3212. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3209-3212.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embretson J. E., Temin H. M. Lack of competition results in efficient packaging of heterologous murine retroviral RNAs and reticuloendotheliosis virus encapsidation-minus RNAs by the reticuloendotheliosis virus helper cell line. J Virol. 1987 Sep;61(9):2675–2683. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.9.2675-2683.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerman M., Temin H. M. Comparison of promoter suppression in avian and murine retrovirus vectors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986 Dec 9;14(23):9381–9396. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.23.9381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerman M., Temin H. M. Genes with promoters in retrovirus vectors can be independently suppressed by an epigenetic mechanism. Cell. 1984 Dec;39(3 Pt 2):449–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann T. Progress toward human gene therapy. Science. 1989 Jun 16;244(4910):1275–1281. doi: 10.1126/science.2660259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilboa E. Retroviral gene transfer: applications to human therapy. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1990;352:301–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritz L., Davies J. Plasmid-encoded hygromycin B resistance: the sequence of hygromycin B phosphotransferase gene and its expression in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1983 Nov;25(2-3):179–188. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley R. G., Covarrubias L., Hawley T., Mintz B. Handicapped retroviral vectors efficiently transduce foreign genes into hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Apr;84(8):2406–2410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki K., Temin H. M. The U3 region is not necessary for 3' end formation of spleen necrosis virus RNA. J Virol. 1990 Dec;64(12):6329–6334. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6329-6334.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K. A., Luciw P. A., Duchange N. Structural arrangements of transcription control domains within the 5'-untranslated leader regions of the HIV-1 and HIV-2 promoters. Genes Dev. 1988 Sep;2(9):1101–1114. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.9.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen R. A., Rothstein S. J., Reznikoff W. S. A restriction enzyme cleavage map of Tn5 and location of a region encoding neomycin resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;177(1):65–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00267254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai S., Nishizawa M. New procedure for DNA transfection with polycation and dimethyl sulfoxide. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Jun;4(6):1172–1174. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.6.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn D. B., Anderson W. F., Blaese R. M. Gene therapy for genetic diseases. Cancer Invest. 1989;7(2):179–192. doi: 10.3109/07357908909038283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linial M., Groudine M. Transcription of three c-myc exons is enhanced in chicken bursal lymphoma cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Jan;82(1):53–57. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan R. A., Anderson W. F. Human gene therapy. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:191–217. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson P., Temin H. M., Dornburg R. Unusually high frequency of reconstitution of long terminal repeats in U3-minus retrovirus vectors by DNA recombination or gene conversion. J Virol. 1992 Mar;66(3):1336–1343. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1336-1343.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne G. S., Bishop J. M., Varmus H. E. Multiple arrangements of viral DNA and an activated host oncogene in bursal lymphomas. Nature. 1982 Jan 21;295(5846):209–214. doi: 10.1038/295209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey C. A., Panganiban A. T. Replication of the retroviral terminal repeat sequence during in vivo reverse transcription. J Virol. 1993 Jul;67(7):4114–4121. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4114-4121.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway A. A. Reticuloendotheliosis virus long terminal repeat elements are efficient promoters in cells of various species and tissue origin, including human lymphoid cells. Gene. 1992 Nov 16;121(2):213–218. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheay W., Nelson S., Martinez I., Chu T. H., Bhatia S., Dornburg R. Downstream insertion of the adenovirus tripartite leader sequence enhances expression in universal eukaryotic vectors. Biotechniques. 1993 Nov;15(5):856–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smale S. T., Schmidt M. C., Berk A. J., Baltimore D. Transcriptional activation by Sp1 as directed through TATA or initiator: specific requirement for mammalian transcription factor IID. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Jun;87(12):4509–4513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern E. M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975 Nov 5;98(3):503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temin H. M. Safety considerations in somatic gene therapy of human disease with retrovirus vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 1990 Summer;1(2):111–123. doi: 10.1089/hum.1990.1.2-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S., Temin H. M. Construction of a helper cell line for avian reticuloendotheliosis virus cloning vectors. Mol Cell Biol. 1983 Dec;3(12):2241–2249. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.12.2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis L., Reinberg D. Transcription by RNA polymerase II: initiator-directed formation of transcription-competent complexes. FASEB J. 1992 Nov;6(14):3300–3309. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.14.1426767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westaway D., Payne G., Varmus H. E. Proviral deletions and oncogene base-substitutions in insertionally mutagenized c-myc alleles may contribute to the progression of avian bursal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Feb;81(3):843–847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsen K. C., Eggleton K., Temin H. M. Nucleic acid sequences of the oncogene v-rel in reticuloendotheliosis virus strain T and its cellular homolog, the proto-oncogene c-rel. J Virol. 1984 Oct;52(1):172–182. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.1.172-182.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee J. K., Moores J. C., Jolly D. J., Wolff J. A., Respess J. G., Friedmann T. Gene expression from transcriptionally disabled retroviral vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Aug;84(15):5197–5201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S. F., von Rüden T., Kantoff P. W., Garber C., Seiberg M., Rüther U., Anderson W. F., Wagner E. F., Gilboa E. Self-inactivating retroviral vectors designed for transfer of whole genes into mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 May;83(10):3194–3198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenzie-Gregory B., Sheridan P., Jones K. A., Smale S. T. HIV-1 core promoter lacks a simple initiator element but contains a bipartite activator at the transcription start site. J Biol Chem. 1993 Jul 25;268(21):15823–15832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]