Abstract

A computational comparison of 102 high-resolution (≤1.90 Å) enzyme-dinucleotide (NAD, NADP, FAD) complexes was performed to investigate the role of solvent in dinucleotide recognition by Rossmann fold domains. The typical binding site contains about 9–12 water molecules, and about 30% of the hydrogen bonds between the protein and the dinucleotide are water mediated. Detailed inspection of the structures reveals a structurally conserved water molecule bridging dinucleotides with the well-known glycine-rich phosphate-binding loop. This water molecule displays a conserved hydrogen-bonding pattern. It forms hydrogen bonds to the dinucleotide pyrophosphate, two of the three conserved glycine residues of the phosphate-binding loop, and a residue at the C-terminus of strand four of the Rossmann fold. The conserved water molecule is also present in high-resolution structures of apo enzymes. However, the water molecule is not present in structures displaying significant deviations from the classic Rossmann fold motif, such as having nonstandard topology, containing a very short phosphate-binding loop, or having α-helix "A" oriented perpendicular to the β-sheet. Thus, the conserved water molecule appears to be an inherent structural feature of the classic Rossmann dinucleotide-binding domain.

Keywords: NAD, NADP, FAD, dinucleotide-protein interactions, Rossmann fold, structurally conserved water molecule, molecular recognition

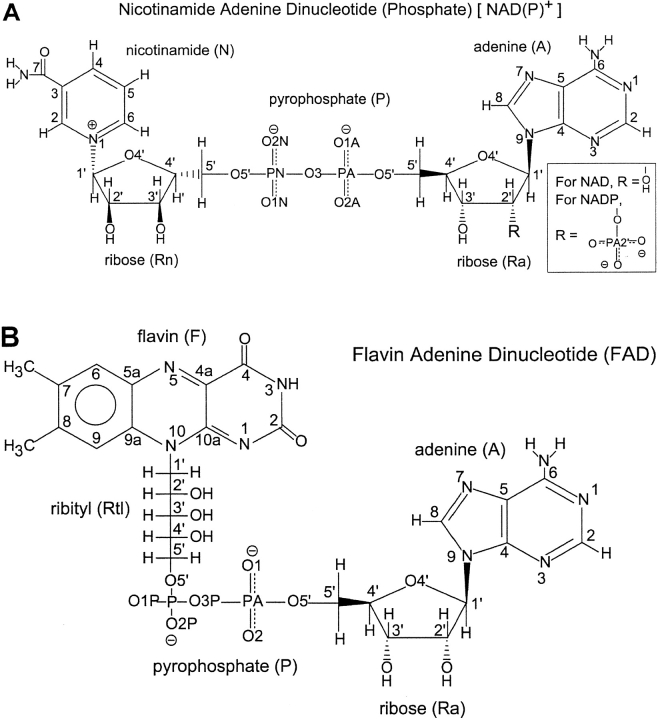

Flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP) serve as enzyme cofactors in many essential biologic processes, such as glycolysis (NAD), the citric acid cycle (FAD and NAD), and photosynthesis (NADP) (Fig. 1 ▶).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures and nomenclature for (A) NAD(P)+ and (B) FAD.

Because of the central role played by adenine dinucleotides in biologic redox chemistry, many dinucleotide-dependent enzymes are potential drug design targets for the treatment of cancer (Konno et al. 1991; Nagai et al. 1991; Franchetti et al. 1998; Faig et al. 2001), bacterial infections (Zhang et al. 1999), and trypanosomal diseases (Verlinde et al. 1994; Verlinde and Hol 1994; Van Calenbergh et al. 1995; Aronov et al. 1998; Bressi et al. 2001). Knowledge of the structural and dynamic features that govern dinucleotide recognition by enzymes is important for understanding the many biochemical roles of dinucleotides and for designing analogs for therapeutic applications.

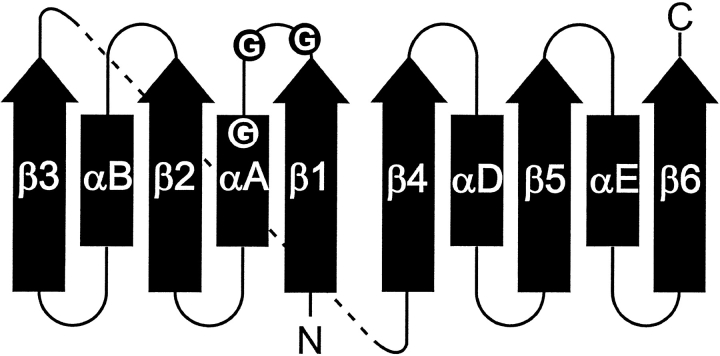

The Rossmann fold was first identified in dinucleotide-binding proteins (Rossmann et al. 1974) and remains one of the most thoroughly studied dinucleotide-binding folds. The Rossmann fold, or mononucleotide-binding motif, is a single βαβαβ motif that binds a mononucleotide. The fold that binds NAD and NADP consists of two mononucleotide-binding motifs that are structurally related by a pseudo twofold rotation, with the most N-terminal strands adjacent to each other (Fig. 2 ▶). Together, the two βαβαβ motifs form a six-stranded parallel β-sheet flanked by α-helices, with relative strand order 321456. The fold that binds FAD typically contains one mononucleotide-binding motif with two additional parallel β-strands, giving a relative strand order of 32145 (Murzin et al. 1995).

Fig. 2.

Classic Rossmann fold topology. The arrows designate β-strands and rectangles denote α-helices. The circles represent conserved glycine residues.

Although dinucleotide-binding domains show very low overall sequence homology, large portions of their protein backbones superimpose very well (Branden and Tooze 1991). However, there are two common sequence features. First, a glycine-rich phosphate-binding loop connects the C-terminus of β1 with the N-terminus of αA (Wierenga et al. 1985) (Fig. 2 ▶). Typically, this loop contains three conserved glycine residues arranged in patterns such as GXGXXG. Mutations in the conserved glycine residues of the loop have been correlated with attenuation or elimination of enzyme activity (Rescigno and Perham 1994; Nishiya and Imanaka 1996; Eschenbrenner et al. 2001) and also with disease (van Grunsven et al. 1998). The second feature is a side chain interaction with the adenine ribose group of the dinucleotide. In NAD- and FAD-binding Rossmann fold proteins, the carboxylate of Asp or Glu interacts with the adenine ribose hydroxyls. In contrast, NADP-binding proteins typically have Arg interacting with the monophosphate at the O2` position of adenine ribose (Branden and Tooze 1991).

The conserved characteristics of dinucleotide-binding proteins have been described in several studies (Rossmann et al. 1974; Lesk 1995); however, the role that structural water plays in dinucleotide recognition has not been extensively analyzed. Five years ago, Carugo and Argos (1997) reported a study of NAD(P)–protein interactions using a data set of 32 NAD(P)–enzyme complexes representing 19 enzymes. The resolution of these structures ranged from 1.6 to 3.20 Å, averaging 2.30 Å, and only eight structures had 1.9 Å resolution or better. Since their work, many high-resolution (≤1.90 Å) structures have become available for study. Here we describe the results of a survey of 102 high-resolution enzyme/dinucleotide complexes that display the Rossmann dinucleotide-binding fold. These higher resolution structures allow an accurate description of the role of solvent in dinucleotide recognition. We find that bridging water molecules contributes significantly to the dinucleotide-binding interface in all of the enzymes studied. Moreover, we identified a structurally conserved water molecule that links, through hydrogen bonding, the glycine-rich loop and the dinucleotide pyrophosphate moiety. We assert that this conserved water molecule is an integral characteristic of dinucleotide-binding Rossmann fold domains, and thus it contributes significantly to dinucleotide recognition.

Results

Data set of structures analyzed

All crystal structures (as of January 2002) in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Berman et al. 2000) with NAD(P) or FAD (Fig. 1 ▶) bound to a Rossmann fold motif and having a resolution of 1.9 Å or better were selected for analysis. The resulting data set consists of 102 structures, and represents 43 enzymes and 40 species (Tables 1, 2, and 3). The crystallographic resolution ranges from 1.15 to 1.90 Å, averaging 1.70 Å. Notwithstanding our conservative resolution cutoff, this study is one of the largest comparisons of dinucleotide-binding proteins performed to date.

Table 1.

NAD-binding proteins

| Enzyme | Species | PDB codes and references | Sequence pattern | Wat |

| (G...XGXXG) | ||||

| Alcohol dehydrogenase | Equus caballus | 1EE2 (Adolph et al. 2000); 1HET, 1HEU (Meijers et al. 2001); 20HX (AI-Karadaghi et al. 1994); 3BTO (Cho et al. 1997) | G...LGGVG | ✓ |

| 3-Dehydroquinate synthase | Aspergillus nidulans | 1DQS(Carpenter et al. 1998) | G...GGVIG | |

| GAPDH | Bacillus stearothermophilus | 1GD1 (Skarzynski et al. 1987) | G...PGRIG | ✓ |

| Escherichia coli | 1GAD (Duee et al. 1996) | G...PGRIG | ✓ | |

| l-3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA dh | Homo sapiens | 1F0Y (Barycki et al. 2000) | G...GGLMG | ✓ |

| d-2-Hydroxyisocaproate dh | Lactobacillus casei | 1DXY (Dengler et al. 1997) | G...TGHIG | ✓ |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | Plasmodium falciparum | 1LDG (Dunn et al. 1996) | G...SGMIG | ✓ |

| Phenylalanine dh | Rhodococcus sp, M4 | 1BW9 (Vanhooke et al. 1999); 1C1D, 1C1X (Brunhuber et al. 2000) | G...LGAVG | ✓ |

| (G..XXGXXG) | ||||

| dTDP-Glucose 4,6- dehydratase | Escherichia coli | 1BXK (Hegeman et al. 2001) | G..GAGFIG | ✓ |

| Malate dehydrogenase | Escherichia coli | 1EMD (Hall and Banaszak 1993) | G..AAGGIG | ✓ |

| Thermus flavus | 1BMD (Kelly et al. 1993) | G..AAGQIG | ✓ | |

| Sulfolipid biosynthesis | Arabidopsis thaliana | 1QRR (Mulichak et al. 1999) | G..GDGYCG | ✓ |

| UDP-Galactose 4-epimerase | Escherichia coli | 1NAH (Thoden et al. 1996a); 1UDA, 1UDB, 1UDC (Thoden et al. 1997); 1XEL (Thoden et al. 1996c); 2UDP (Thoden et al. 1996b) | G..GSGYIG | ✓ |

| Homo sapiens | 1EK5, 1EK6 (Thoden et al. 2000); 1HZJ (Thoden et al. 2001) | G..GAGYIG | ✓ | |

| (G..XXXGXG) | ||||

| 7-α-Hydroxysteroid dh | Escherichia coli | 1FMC (Tanaka et al. 1996b) | G..AGAGIG | ✓ |

| d-Glucose-1-dehydrogenase | Bacillus megaterium | 1GCO (Yamamoto et al. 2001) | G..SSTGLG | ✓ |

| l-3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA dh | Rattus norvegicus | 1E6W (Powell et al. 2000) | G..GASGLG | ✓ |

| meso-2,3-Butanediol dh | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1GEG (Otagiri et al. 2001) | G..AGQGIG | ✓ |

| (GXXXXXXXG) | ||||

| Enoyl ACP reductase | Brassica napus | 1D7O (Roujeinikova et al. 1999); 1ENO (Rafferty et al. 1995) | GIADDNGYG | ✓ |

| Escherichia coli | 1QG6 (Ward et al. 1999); 1QSG (Stewart et al. 1999) | GVASKLSIA | ✓ | |

| NMN adenylyltransferase | Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum | 1EJ2 (Saridakis et al. 2001) | GRMQPFHRG |

Table 2.

NADP-binding proteins

| Enzyme | Species | PDB codes and references | Sequence pattern | Wat |

| (G...XGXXG) | ||||

| Acetohydroxy acid isomeroreductase | Spinacia oleracea | 1YVE(Biou et al. 1997) | G...WGSQA | ✓ |

| Adrenodoxin reductase | Bos taurus | 1E1M(Ziegler and Schulz 2000) | G...QGNVA | ✓ |

| Glutathione reductase | Homo sapiens | 1GRB(Karplus and Schulz 1989) | G...AGYIA | ✓ |

| NADP(H) transhydrogenase | Bos taurus | 1D4O(Prasad et al. 1999) | G...YGLCA | |

| Biliverdin-IX β reductase | Homo sapiens | 1HDO, 1HE2, 1HE3, 1HE4, 1HE5(Pereira et al. 2001) | (G..XXGXXG) G..ATGQTG | ✓ |

| Coenzyme F420H2: NADP+- oxidoreductase (Fno) | Archaeoglobus fulgidus | 1JAY(Warkentin et al. 2001) | G..GTGNLG | ✓ |

| GDP 4-keto-6-deoxy-d- mannose epimerase rd | Escherichia coli | 1E6U(Rosano et al. 2000) | G..HRGMVG | ✓ |

| l-Lactate/malate dh | Methanococcus jannaschil | 1HYE(Lee et al. 2001) | G..ASGRVG | ✓ |

| 1,3,6,8-Tetrahydroxynaphthalene reductase | Magnaporthe grisea | 1JA9(Liao et al. 2001) | (G..XXXGXG) G..AGRGIG | ✓ |

| Carbonyl reductase | Mus musculus | 1CYD(Tanaka et al. 1996a) | G..AGKGIG | ✓ |

| Mannitol dehydrogenase | Agaricus bisporus | 1H5Q(Horer et al. 2001) | G..GNRGIG | ✓ |

| Nitric-oxide synthase | Rattus norvegicus | 1F20(Zhang et al. 2001) | G..PGTG(IA) | |

| Sepiapterin reductase | Mus musculus | 1OAA(Auerbach et al. 1997) | G..ASRGFG | ✓ |

| Tropinone reductase-II | Datura stramonium | 2AE2(Yamashita et al. 1999) | G..GSRGIG | ✓ |

| (G..XXXXXG) | ||||

| Methylenetetrahydrofolate dh | Homo sapiens | 1A4I(Allaire et al. 1998) | G..RSKIVG | ✓ |

| Pteridine reductase | Leishmania major | 1E7W(Gourley et al. 2001) | G..AAKRLG | ✓ |

| Other | ||||

| Dihydrofolate reductase | Candida albicans | 1AI9, 1AOE(Whitlow et al. 1997); 1IA1, 1IA2, 1IA3, 1IA4(Whitlow et al. 2001) | GRKT | |

| Escherichia coli | 1RA2, 1RA3, 1RA4, 1RC4, 1RX2, 1RX9(Sawaya and Kraut 1997) | GGGRV | ||

| Gallus gallus | 8DFR(Matthews et al. 1985) | GKKT | ||

| Lactobacillus casei | 3DFR(Bolin et al. 1982) | GRRT | ||

| Myobacterium tuberculosis | 1DF7, 1DG7(Li et al. 2000) | GRRT | ||

| Pneumocystis carinii | 1DYR(Champness et al. 1994); 2CD2(Cody et al. 1999) | GRKT |

Table 3.

FAD-binding proteins

| Enzyme | Species | PDB codes and references | Sequence pattern | Wat |

| (G...XGXXG) | ||||

| Adrenodoxin reductase | Bos taurus | 1CJC(Ziegler et al. 1999); 1E1M(Ziegler and Schulz 2000) | G...SGPAG | ✓ |

| Alkyl hydroperoxide rd | Escherichia coli | 1FL2(Bieger and Essen 2001) | G...SGPAG | ✓ |

| Cholesterol oxidase | Brevibacterium sterolicum | 1COY, 3COX (Li et al. 1993) | G...SGYGG | ✓ |

| Streptomyces sp. | 1B4V(Yue et al. 1999) | G...TGYGA | ✓ | |

| d-Amino acid oxidase | Rhodotorula gracilis | 1C0K, 1C0L, 1C0P(Umhau et al. 2000) | G...SGVIG | ✓ |

| Dihydropyrimidine dh | Sus scrofa | 1H7W(Dobritzsch et al. 2001) | G...AGPAS | ✓ |

| Flavocytochrome C3 | Shewanella frigidimarina | 1QJD(Taylor et al. 1999) | G...SGGAG | ✓ |

| Glucose oxidase | Aspergillus niger | 1CF3(Wohlfahrt et al. 1999) | G...GGLTG | ✓ |

| Penicillium amagasakiense | 1GPE(Wohlfahrt et al. 1999) | G...GGLTG | ✓ | |

| Glutathione reductase | Escherichia coli | 1GER(Mittl and Schulz 1994) | G...GGSGG | ✓ |

| Homo sapiens | 1DNC, 1GSN(Becker et al. 1998); 1GRB (Karplus and Schulz 1989); 3GRS (Karplus and Schulz 1987) | G...CGSGG | ✓ | |

| p-Hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase | Pseudomonas fluorescens | 1PBE(Schreuder et al. 1989) | G...AGPGC | ✓ |

| Polyamine oxidase | Zea mays | 1B37, 1B5Q(Binda et al. 1999); 1H82, 1H83(Binda et al. 2001) | G...AGMSG | ✓ |

| Sarcosine oxidase | Bacillus sp. | 1EL5, 1EL7, 1EL8(Wagner et al. 2000) | G...AGSMG | ✓ |

| Trypanothione reductase | Crithidia fasciculata | 1FEC(Strickland and Karplus 1995) | G...AGSGG | ✓ |

| Other | ||||

| Quinone reductase | Homo sapiens | 1D4A(Faig et al. 2000); 1H69(Falg et al. 2001); 1KBQ(Winski et al. 2001) | AHSERTSFNY |

Tables 1, 2, and 3 show alignments of the glycine-rich pyrophosphate-binding sequences for the enzymes studied. The majority of enzymes in our data set display the pyrophosphate-binding loop sequence patterns GXGXXG, GXXGXXG, or GXXXGXG, where G is Gly and X is any amino acid residue. Two enzymes have the sequence pattern GXXXXXG, and two have the pattern GXXXXXXXG. Note that sometimes Ala substitutes for the last Gly, and, in one case, dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, Ser substitutes for the last Gly. Note that all the FAD-binding proteins in our data set except one have the phosphate-binding loop sequence GXGXXG. Quinone reductase does not have a glycine-rich loop, although it is still classified as a Rossmann fold protein.

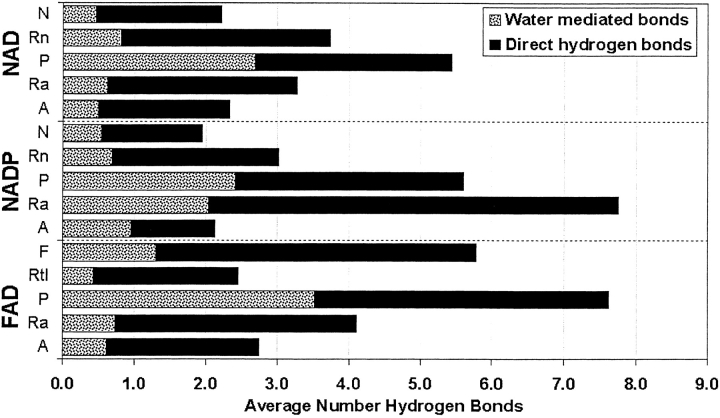

Identification of a structurally conserved water molecule

All the structures in our database have several water molecules in the interface between the dinucleotide and the protein. On average, FAD-, NADP-, and NAD-binding proteins accommodate about 12, 11, and 9 interfacial (within 3.75Å of the protein and dinucleotide) water molecules per dinucleotide-binding site, respectively. As expected, many of these interfacial water molecules hydrogen bond to both the dinucleotide and the protein, thus forming water-mediated hydrogen bonds. Figure 3 ▶ shows the average numbers of direct and water-mediated hydrogen bonds formed between the protein and the five groups of each of the dinucleotides. Water-mediated hydrogen bonds comprise 29, 32, and 29% of the protein/dinucleotide hydrogen bonds for NAD, NADP, and FAD, respectively. The pyrophosphate group forms almost as many water-mediated hydrogen bonds (2.7 for NAD, 2.4 for NADP, and 3.5 for FAD) as direct hydrogen bonds (2.8 for NAD, 3.2 for NADP, and 4.1 for FAD) to the protein. The remaining groups average one or fewer water-mediated hydrogen bonds, with the exception of adenine ribose in NADP. This group averages more than two water-mediated hydrogen bonds, a result due to its monophosphate. Thus, bridging water molecules are concentrated around the pyrophosphate and monophosphate groups, although they are commonly found associated with the rest of the dinucleotide as well.

Fig. 3 .

Protein/dinucleotide hydrogen bonds by groups. Hydrogen bonds to each group are divided into direct and water-mediated categories. Their sum represents the total number of hydrogen bonds between the protein and dinucleotide. The various groups of the three dinucleotides are abbreviated as follows: N, nicotinamide; Rn, nicotinamide ribose; P, pyrophosphate; Ra, adenine ribose; A, adenine; F, flavin isoalloxazine; Rtl, flavin ribityl side chain.

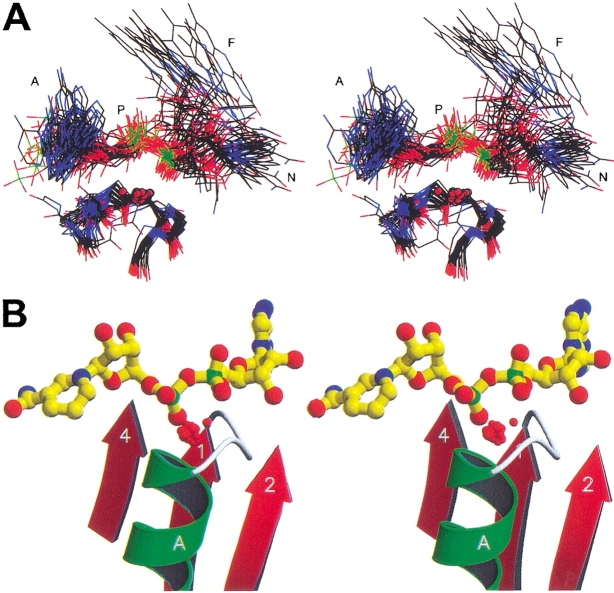

The presence of numerous water-mediated hydrogen bonds between protein and dinucleotides implicates water as a significant component of dinucleotide recognition. Superimposition of the structures allowed us to identify whether any of the bridging water molecules bound in structurally conserved sites. The crystal structures were superimposed using the coordinates of only three alpha carbon atoms within the glycine-rich loop, as described in Materials and Methods. This analysis revealed a structurally conserved water molecule located at the N-terminus of the phosphate binding helix (i.e., αA) in 77 structures, which represents 37 of 43 enzymes studied. The structures displaying the conserved water molecule are indicated by the checkmark in Tables 1–3. Figure 4A ▶ shows the superimposed phosphate binding loops, cofactors, and structurally conserved water molecules of these 37 enzymes. Note the almost perfect superimposition of the phosphate moiety, the glycine-rich loop, and the structurally conserved water molecule of these different structures. In contrast, adenine, nicotinamide, and flavin do not superimpose as well. Figure 4B ▶ shows the structurally conserved water molecule from 77 structures after superposition onto the alcohol dehydrogenase structure 1HET, as described in Materials and Methods. Also shown are secondary structurally elements and NADH of 1HET. These water molecules have an RMSD of 0.5 Å from a reference water molecule, which indicates that the water molecules occupy essentially the same location in their respective structures. As will be discussed below, the six enzymes that do not bind this water molecule show significant deviations from the classic Rossmann fold motif.

Fig. 4.

Superposition of protein structures. (A) Stereoimage showing the dinucleotides, phosphate-binding loops, and structurally conserved water molecules of 37 enzymes. (B) Stereoimage showing the structurally conserved water molecules of 77 structures superimposed according to their glycine-rich loops as described in Materials and Methods. The NADH and protein shown are from alcohol dehydrogenase (1HET). In both (A) and (B), the oxygen atoms of the water molecules are shown as red spheres with 1/5 van der Waals radii. Figures created using MOLSCRIPT (Kraulis 1991) and Raster3D (Merritt and Bacon 1997).

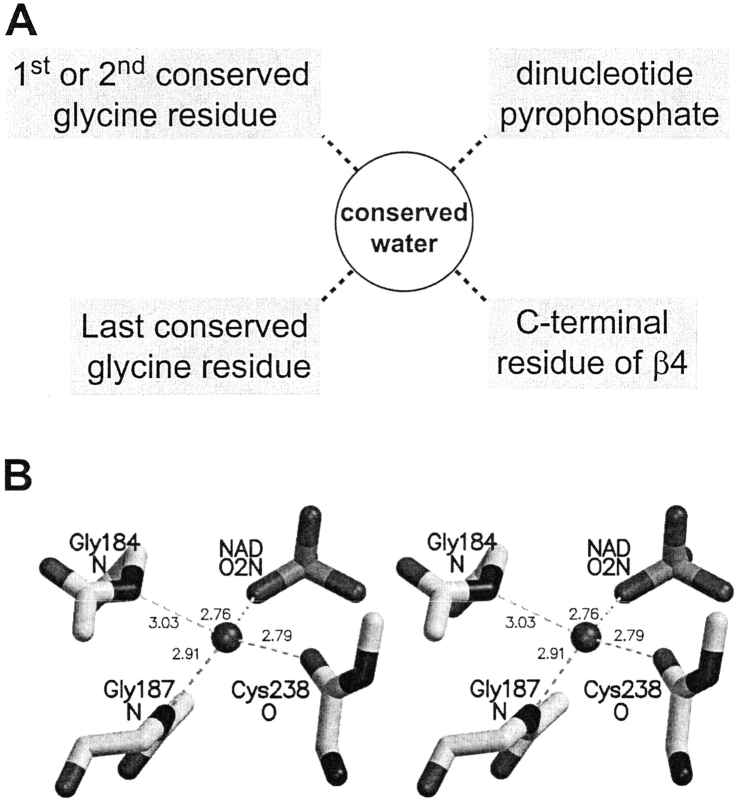

Hydrogen bonds formed by the structurally conserved water molecule

The structurally conserved water molecule typically makes four hydrogen bonds. Two of the four bonds are invariant, and two vary according to the sequence pattern of the glycine-rich phosphate-binding loop. The hydrogen-bonding pattern of the conserved water molecule is shown schematically in Figure 5A ▶, and an example of this hydrogen bond coordination is shown in Figure 5B ▶. A table detailing the hydrogen bonding partners of the structurally conserved water molecule in each dinucleotide-binding site is provided in the electronic supplement.

Fig. 5.

Hydrogen bonding patterns of the structurally conserved water molecule. (A) Schematic of the hydrogen bonds formed by the structurally conserved water molecule. The dotted lines denote hydrogen bonds. (B) An example of the structurally conserved water molecule's hydrogen bond coordination as seen in phenylalanine dehydrogenase of Rhodococcus sp. M4 (PDB code 1C1D). Gly184 and Gly187 donate hydrogen bonds via their amide nitrogens, while the carbonyl of Cys238 accepts a hydrogen bond. Only backbone atoms are shown. Distances are in angstroms.

The two invariant hydrogen bonds formed by the conserved water molecule involve pyrophosphate and the amine of the last conserved Gly (Fig. 5 ▶). Thus, the water molecule always links the pyrophosphate to the glycine-rich loop. Moreover, the interaction with the pyrophosphate is stereospecific. Although the pyrophosphate is not chiral, the oxygen atoms are distinct stereochemically (Schultze and Feigon 1997). Almost without exception, the pyrophosphate atom that interacts with the structurally conserved water molecule is O2N in the case of NAD- or NADP-binding proteins. In FAD-binding proteins, however, it is always O1P (i.e., equivalent to O1N of NAD[P]), which interacts with the structurally conserved water molecule. Interestingly, the only two structures in our study that have both FAD and NADP bound are also the only ones in which NADP binds to the structurally conserved water molecule via its pyrophosphate atom O1N (see 1E1M and 1GRB).

The partners for the other two hydrogen bonds formed by the conserved water molecule depend upon the sequence of the glycine-rich loop. One sequence-dependent hydrogen bond involves either the first or second conserved Gly. This bond occurs in structures with the sequence patterns GXGXXG, GXXGXXG, and GXXXXXXXG. It also occurs in seven of the eight structures with the sequence pattern GXXXGXG, but does not occur in structures with the sequence pattern GXXXXXG. In structures with the sequence GXGXXG, the water molecule forms a hydrogen bond with the amino group of the second conserved Gly. An example of this hydrogen-bonding pattern is shown in Figure 5B ▶. In structures with the sequence patterns GXXGXXG, GXXXGXG, and GXXXXXXXG, the water molecule instead forms a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl group of the first conserved Gly.

The second sequence-dependent hydrogen bond involves a C-terminal residue of β4. In structures with the pattern GXGXXG and GXXGXXG, this hydrogen bond usually involves the backbone carbonyl of either a small residue or a hydrophobic residue (i.e., Ala, Cys, Gly, Leu, Phe, Ser, or Val for the structures studied). However, occasionally it will involve the hydroxyl of Ser or Thr. In structures with the sequence pattern GXXXGXG, the C-terminal residue of β4 usually donates a hydrogen bond via the side chain of an Asn. In structures with the sequence pattern GXXXXXXXG, the C-terminal residue of β4 donates a hydrogen bond via a Ser hydroxyl.

The hydrogen bonding patterns observed in structures with the sequence GXXXXXG are minor variations of the paradigm described above. There are two such structures in our data set, 1A4I (human methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase) and 1E7W (Leishmania major pteridine reductase). The water molecule of 1A4I does not superimpose as well as the others, as is evident from its 1.1-Å separation from the others in Figure 4 ▶. The conserved water molecule of 1A4I displays a hydrogen-bonding pattern identical to that of GXGXXG structures, with Ser of its GRSKIVG sequence playing the role of the second conserved Gly. On the other hand, the hydrogen bond coordination in 1E7W is very similar to that of proteins with the sequence GXXXGXG. The only exception is that the first conserved glycine residue interacts with the structurally conserved water molecule via another water molecule inside the phosphate-binding loop. To our knowledge, this is the only case in which the structurally conserved water molecule forms a hydrogen bond with another water molecule.

Finally, the conserved water molecule sometimes forms a fifth hydrogen bond. For example, in structures with the sequence pattern GXXXGXG, the conserved water molecule forms a fifth hydrogen bond with the carbonyl of the third "X" residue. It is also common to see the methylene of the second or third conserved Gly within hydrogen bonding distance of the structurally conserved water molecule. Several studies have mentioned the presence of CH . . . O hydrogen bonds in NAD(P) interfaces (Carugo and Argos 1997; Chu and Hwang 1998). Although CH . . . O hydrogen bonds are somewhat unconventional, the methylene of glycine can theoretically form a significant hydrogen bond. Such a bond would have about half the energy of a typical hydrogen bond from water (Scheiner et al. 2001).

Structures lacking the conserved water molecule

Six enzymes (3-dehydroquinate synthase, NMN adenylyltransferase, NADP[H] transhydrogenase, nitric-oxide synthase, dihydrofolate reductase, quinone reductase) lack the structurally conserved water molecule (Tables 1–3). These enzymes show significant deviations from the standard Rossmann fold motif in terms of their sequence and/or structure. Thus, the conserved water molecule is found only in classic Rossmann fold structures.

Some of the unusual features of these enzymes are obvious. For example, 3-dehydroquinate synthase has a nonstandard topology in which the phosphate-binding loop connects β4 and αD instead of β1 and αA. No other enzyme in our data set has this unusual topology. In NADP(H) transhydrogenase and dihydrofolate reductase, the long axis of αA runs perpendicular to the β-sheet rather than parallel to it as in all the other structures. NMN adenylyltransferase differs from the other enzymes in our data set because NAD is a product of catalysis rather than a redox cofactor. The pyrophosphate binds near the beginning of the phosphate-binding loop rather than at the end of the loop near the N-terminus of αA as occurs in the classic Rossmann fold structures. Thus, the pyrophosphate interacts with the Rossmann fold in a fundamentally unique way that is related to the nature of the reaction catalyzed.

3-Dehydroquinate synthase, NADP(H) transhydrogenase, and nitric-oxide synthase show a subtle, but very important, deviation from the standard Rossmann fold structure concerning the hydrogen bonding potential of the last residue of their phosphate-binding sequences. In the classic Rossmann fold, this residue occurs at the beginning of αA (Fig. 2 ▶) and its amino group donates one of the invariant hydrogen bonds to the structurally conserved water molecule (Fig. 5A ▶). However, in 3-dehydroquinate synthase, NADP(H) transhydrogenase, and nitric-oxide synthase, this residue cannot hydrogen bond to a water molecule because it is the fifth or later residue of the helix, and its amino group must form an "n + 4" α-helix hydrogen bond with the carbonyl four residues preceding it in the sequence.

Lastly, dihydrofolate reductase and quinone reductase deviate from the classic Rossmann fold because of the length and sequence, respectively, of their phosphate binding loops. The dihydrofolate reductases have short phosphate-binding loops. Their loops consist of four to five residues compared to six to nine residues in the other structures (Tables 1–3). The resulting loop between β1 and αA is not wide enough to accommodate a water molecule. Quinone reductase, on the other hand, has no glycine residues in its phosphate-binding loop. This is a critical feature, because, in the classic Rossmann fold motif, the first Gly of the phosphate-binding loop always occupies the first quadrant (i.e., φ > 0, ξ > 0) of the Ramachandran plot. This region of φ–ξ space is typically inaccessible to nonglycine residues. Thus, the phosphate-binding loop of quinone reductase cannot adopt the backbone conformations typically observed in classic Rossmann fold proteins.

Discussion

Bridging water molecules

NAD, NADP, and FAD have extraordinary hydrogen bonding potential. They have 19, 22, and 22 polar nitrogen and oxygen atoms, respectively. Therefore, it is not surprising that NAD, NADP, and FAD form about 16, 19, and 23 hydrogen bonds with the protein. However, the observation that water molecules mediate about 30% of these hydrogen bonds is a novel result, and indicates that bridging water is an important component of dinucleotide recognition.

More generally, our results demonstrate a pitfall of ignoring water molecules when analyzing protein crystal structures. In the present case, neglecting water molecules would have given the incorrect impression that Rossmann fold domains greatly underutilize the hydrogen bonding potential of dinucleotides. This issue is critical for ligand docking calculations and structure-based drug design and optimization (Marrone et al. 1997; Raymer et al. 1997).

The result that water molecules are important in dinucleotide recognition is perhaps not surprising, because solvent is important in protein recognition of small molecules, DNA, and protein. For example, about 40% of all protein–DNA hydrogen bonds are water mediated (Luscombe et al. 2001), and protein–protein interfaces contain an average of about 22 water molecules and 11 water-mediated hydrogen bonds (Janin 1999).

Structurally conserved water molecule

We discovered a water molecule that bridges the glycine-rich loop and the pyrophosphate in 77 of the 102 structures studied. The structurally conserved water molecule binds at the N-terminus of αA and it displays a conserved hydrogen-bonding pattern (Fig. 4 ▶). Structurally conserved water molecules have also been identified in fatty acid binding proteins (Likic et al. 2000) and serine proteases (Sreenivasan and Axelsen 1992). Water molecules of ligand-binding sites have also been found to be conserved between pairs of homologous proteins from different species (Poornima and Dean 1995). Several authors have noted the presence of a water molecule that we refer to as the structurally conserved water molecule, but they did not realize its ubiquity in Rossmann fold domains or its conserved hydrogen-bonding pattern (Lamzin et al. 1994; Dessen et al. 1995; Rafferty et al. 1995; Dengler et al. 1997; Adolph et al. 2000; Thoden et al. 2000; Horer et al. 2001; Pantano et al. 2002). In NAD-binding proteins, we found the water molecule to be more highly conserved than the carboxylate interaction with the adenine-ribose diol. Not only do the structures in our data set represent a significant cross section of enzymes, but they also represent a variety of species and even biologic kingdoms. Such structural conservation argues strongly for an important functional role.

The structurally conserved water molecule typically forms hydrogen bonds with two of the three conserved glycine residues, a C-terminal residue of β4, and the dinucleotide pyrophosphate. The water molecule always forms hydrogen bonds to both the pyrophosphate and the last conserved Gly, which is part of helix αA. This water-mediated hydrogen bond is significant, because previous studies have noted that direct hydrogen bonding between αA and the pyrophosphate is not optimal. Based on this observation, a favorable electrostatic interaction between the helix dipole of αA and the pyrophosphate has been considered an important factor in dinucleotide recognition (Wierenga et al. 1985). This conclusion, however, was based on analyses of crystal structures that generally lacked water molecules; therefore, water-mediated hydrogen bonds could not be considered. Including water-mediated hydrogen bonds almost doubles the number of observed hydrogen bonds between the protein and pyrophosphate. Due to the high solvent content about the pyrophosphate and the several water-mediated hydrogen bonds, we wonder if the helix dipole would be an important contributing factor to pyrophosphate binding. Additional studies would be needed to resolve this issue.

Structures that exhibit the classic Rossmann fold motif bind the structurally conserved water molecule, whereas structures that have major deviations from the standard Rossmann fold do not. The following classic features are shared by all the structures bearing the conserved water molecule. The β-sheet topology is 321456 for NAD(P)- and 32145 for FAD-binding domains, and αA is parallel to the β-sheet. The phosphate-binding loop is at least six residues long, and it contains Gly at the first position. The last residue of the phosphate-binding sequence is located at the beginning of αA where its amino group is available to hydrogen bond to the water.

The conserved water molecule appears to be a structural feature inherent to the classic Rossmann dinucleotide-binding fold itself, because this water molecule is also present in apo structures. Examples of such apo structures include the FAD utilizing enzyme l-aspartate oxidase, 1CHU (Mattevi et al. 1999), the NAD enzyme malate dehydrogenase, 1MLD (Gleason et al. 1994), and the NADP enzyme secondary alcohol dehydrogenase, 1PED (Korkhin et al. 1998). Some of the FAD-containing structures in our study also contained NADP-binding domains that lacked NADP. All of these apo-NADP domains also contained the structurally conserved water molecule.

There are several potential functional roles for the conserved water molecule in dinucleotide recognition. First, it could help maintain the unique conformation of the glycine-rich phosphate-binding loop. This role is suggested by the presence of the water molecule in apo structures of dinucleotide-binding enzymes, and by the fact that at least two residues of the glycine-rich loop hydrogen bond to the water molecule (Fig. 5A ▶). These residues interact with the water molecule through their backbone carbonyl or amide groups; thus, these protein–water hydrogen bonds appear to stabilize the backbone conformation of the loop by maintaining these residues in specific phi and psi ranges. A second functional role for the water molecule is that it helps to maintain the cofactor in an extended conformation. Experimental (Zens et al. 1976) and computational studies (Smith and Tanner 1999,Smith and Tanner 2000) of NAD+ in various solvents suggest that NAD+ is folded in aqueous solution such that the two bases stack against each other at a distance of about 4–5 Å. Thus, NAD+ must unfold into an extended conformation during complexation to the enzyme. The extent to which the enzyme facilitates the unfolding of the cofactor is unknown; however, the protein presumably provides interactions that encourage and maintain the extended geometry. The hydrogen bonding and steric interactions provided by the conserved water molecule could help constrain the dihedral angles of the pyrophosphate group to the values observed in enzyme/dinucleotide complexes. A third possible functional role for the conserved water molecule is that the sequence independent hydrogen bond between the dinucleotide pyrophosphate and the water molecule (Fig. 5 ▶) presumably provides a favorable enthalpic contribution to the free energy of binding. Future studies will explore these potential roles to evaluate their possible contributions to dinucleotide recognition and binding.

Materials and methods

Selection and preparation of structures

Crystal structures of enzyme/dinucleotide complexes that contained at least one Rossmann fold were selected for analysis. This selection was restricted to structures having resolutions of 1.90 Å or better to ensure reliable solvent structure. Excluded were any structures having mutations other than for expression purposes and any structures having chemical modifications in the active site. One hundred two structures, representing 43 enzymes, were included in the study (Tables 1–3). Some of the proteins had representatives in multiple species.

To ensure an accurate accounting of interactions, including those involving solvent positions near subunit interfaces, the biologically relevant oligomeric forms of the enzyme were used. Typically, we used the "Likely Quaternary Structure" obtained from the European Bioinformatics Institute Macromolecular Structure Database (EBI-MSD) via the OCA-browser interface (http://oca.ebi.ac.uk/oca-bin/ocamain). Using symmetry operators, the EBI generates oligomeric structures from coordinates deposited in the PDB. Each structure downloaded from the EBI-MSD was superimposed onto its parent structure from the PDB using CNS (Brunger et al. 1998) and visualized in O (Jones et al. 1991) to verify the accuracy of the symmetry expansion and to inspect the dinucleotide binding site. In a few cases, the symmetry expansion was incorrect or incomplete, and CNS was used to create the correct quaternary structures from the corresponding PDB structures. In other cases, visual inspection revealed that a few subunits contained incompletely modeled NAD+ molecules. These subunits were omitted from the subsequent analysis. Bound sulfate ions present due to the crystallization medium were removed.

To facilitate comparison, all the structures were superimposed onto a common structure using CNS. Each protein was superimposed onto the ADH structure of Meijers et al. (2001) (1HET) using the α-carbon coordinates of the first, third from last, and last residue of the phosphate-binding loop. The molecular visualization programs O and Protein Explorer (Martz 2001) were used to examine the structures.

Hydrogen bonding calculations

Hydrogen bonds found in biologic molecules typically have an acceptor–donor distance of 2.7–3.2 Å (Jeffrey 1997). For the purposes of our study, the functional definition of a hydrogen bond was the presence of an acceptor and a donor within 3.2 Å of each other. Only nitrogen and oxygen atoms were considered for our hydrogen bonding calculations (i.e., CH. . .O hydrogen bonds were not included in Fig. 3 ▶). Due to the difficult nature of assigning hydrogen atom positions for water molecules and hydroxyl groups, as well as the absence of explicit hydrogen atoms in the crystal structures under study, an angle cutoff was not included in our definition of a hydrogen bond. Based on our functional definition, X-PLOR (Brunger 1992) was used to identify hydrogen bonds.

The data set of structures used in this study contains some redundancy; therefore, hydrogen-bonding calculations for each structure were weighted to avoid biasing the results toward enzymes heavily represented in our data set. Each enzyme contributed equally to the overall average by assigning each structure a weight equal to the inverse of the product of the number of sources per enzyme and the number of structures per source. For example, Table 1 lists three structures of UDP-galactose-4-epimerase from Homo sapiens and six structures from Escherichia coli. Thus, each H. sapiens UDP-galactose-4-epimerase structure would receive a weight of 1/6, while each E. coli UDP-galactose-4-epimerase structure would receive a weight of 1/12. Likewise, because there is only one source and one structure representing 7α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (1FMC), it would receive a weight of 1. In addition, most of the structures used in this analysis are oligomers; therefore, the hydrogen bonding data were averaged over all the subunits within each structure. Each subunit contributed equally to the average for its structure.

Electronic supplemental material

A table listing the atoms within 3.4 Å of the structurally conserved water molecules of the structures surveyed is included as a supplement available at www.proteinscience.org. (Filename: supp.doc. This was created in Microsoft Word for PC.)

Acknowledgments

We thank the Interdisciplinary Plant Group and the Genetics Area Program of the University of Missouri–Columbia for providing predoctoral support for CAB. This project was partially supported by a Big 12 Faculty Fellowship Award to J.J.T.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

A, adenine

ACP, acyl carrier protein

ADH, alcohol dehydrogenase

CNS, crystallography and NMR system

CoA, coenzyme A

dh, dehydrogenase

dTDP, deoxythymidine diphosphate

EBI-MSD, European Bioinformatics Institute Macromolecular Structure Database

FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide

GAPDH, d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

GDP, Guanosine diphosphate

N, nicotinamide

NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

NADP, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

NMN, nicotinamide adenine mononucleotide

P, pyrophosphate

PDB, Protein Data Bank

Ra, adenine ribose

rd, reductase

RMSD, root-mean-square deviation

Rn, nicotinamide ribose

UDP-galactose, uridine 5`-diphosphate galactose

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.0213502.

References

- Adolph, H.W., Zwart, P., Meijers, R., Hubatsch, I., Kiefer, M., Lamzin, V., and Cedergren-Zeppezauer, E. 2000. Structural basis for substrate specificity differences of horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase isozymes. Biochemistry 39 12885–12897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Karadaghi, S., Cedergren-Zeppezauer, E.S., Petratos, K., Hovmoeller, S., Terry, H., Dauter, Z., and Wilson, K.S. 1994. Refined crystal structure of liver alcohol dehydrogenase-NADH complex at 1.8 Å resolution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50 793–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allaire, M., Li, Y., MacKenzie, R.E., and Cygler, M. 1998. The 3-D structure of a folate-dependent dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase bifunctional enzyme at 1.5 Å resolution. Structure 6 173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronov, A.M., Verlinde, C.L., Hol, W.G., and Gelb, M.H. 1998. Selective tight binding inhibitors of trypanosomal glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase via structure-based drug design. J. Med. Chem. 41 4790–4799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach, G., Herrmann, A., Gutlich, M., Fischer, M., Jacob, U., Bacher, A., and Huber, R. 1997. The 1.25 Å crystal structure of sepiapterin reductase reveals its binding mode to pterins and brain neurotransmitters. EMBO J. 16 7219–7230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barycki, J.J., O'Brien, L.K., Strauss, A.W., and Banaszak, L.J. 2000. Sequestration of the active site by interdomain shifting. Crystallographic and spectroscopic evidence for distinct conformations of L-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 275 27186–27196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, K., Savvides, S.N., Keese, M., Schirmer, R.H., and Karplus, P.A. 1998. Enzyme inactivation through sulfhydryl oxidation by physiologic NO-carriers. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5 267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman, H.M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T.N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I.N., and Bourne, P.E. 2000. The Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/). Nucleic Acids Res. 28 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieger, B. and Essen, L.O. 2001. Crystal structure of the catalytic core component of the alkylhydroperoxide reductase AhpF from Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 307 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binda, C., Angelini, R., Federico, R., Ascenzi, P., and Mattevi, A. 2001. Structural bases for inhibitor binding and catalysis in polyamine oxidase. Biochemistry 40 2766–2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binda, C., Coda, A., Angelini, R., Federico, R., Ascenzi, P., and Mattevi, A. 1999. A 30 Å long U-shaped catalytic tunnel in the crystal structure of polyamine oxidase. Struct. Fold. Des. 7 265–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biou, V., Dumas, R., Cohen-Addad, C., Douce, R., Job, D., and Pebay-Peyroula, E. 1997. The crystal structure of plant acetohydroxy acid isomeroreductase complexed with NADPH, two magnesium ions and a herbicidal transition state analog determined at 1.65 Å resolution. EMBO J. 16 3405–3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolin, J.T., Filman, D.J., Matthews, D.A., Hamlin, R.C., and Kraut, J. 1982. Crystal structures of Escherichia coli and Lactobacillus casei dihydrofolate reductase refined at 1.7 Å resolution. I. General features and binding of methotrexate. J. Biol. Chem. 257 13650–13662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branden, C. and Tooze, J. 1991. Chapter 10: Enzymes that bind nucleotides. In Introduction to protein structure, 1st ed., pp. 141–159. Garland Publishing, New York.

- Bressi, J.C., Verlinde, C.L., Aronov, A.M., Shaw, M.L., Shin, S.S., Nguyen, L.N., Suresh, S., Buckner, F.S., Van Voorhis, W.C., Kuntz, I.D., Hol, W.G., and Gelb, M.H. 2001. Adenosine analogues as selective inhibitors of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Trypanosomatidae via structure-based drug design. J. Med. Chem. 44 2080–2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger, A.T. 1992. X-PLOR, version 3.1: A system for X-ray crystallography and NMR. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

- Brunger, A.T., Adams, P.D., Clore, G.M., DeLano, W.L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R.W., Jiang, J.S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N.S., Read, R.J., Rice, L.M., Simonson, T., and Warren, G.L. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunhuber, N.M., Thoden, J.B., Blanchard, J.S., and Vanhooke, J.L. 2000. Rhodococcus L-phenylalanine dehydrogenase: Kinetics, mechanism, and structural basis for catalytic specificity. Biochemistry 39 9174–9187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, E.P., Hawkins, A.R., Frost, J.W., and Brown, K.A. 1998. Structure of dehydroquinate synthase reveals an active site capable of multistep catalysis. Nature 394 299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carugo, O. and Argos, P. 1997. NADP-dependent enzymes. I: Conserved stereochemistry of cofactor binding. Proteins 28 10–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champness, J.N., Achari, A., Ballantine, S.P., Bryant, P.K., Delves, C.J., and Stammers, D.K. 1994. The structure of Pneumocystis carinii dihydrofolate reductase to 1.9 Å resolution. Structure 2 915–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H., Ramaswamy, S., and Plapp, B.V. 1997. Flexibility of liver alcohol dehydrogenase in stereoselective binding of 3-butylthiolane 1-oxides. Biochemistry 36 382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, P.Y. and Hwang, M.J. 1998. New insights for dinucleotide backbone binding in conserved C5`-H . . . O hydrogen bonds. J. Mol. Biol. 279 695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cody, V., Galitsky, N., Rak, D., Luft, J.R., Pangborn, W., and Queener, S.F. 1999. Ligand-induced conformational changes in the crystal structures of Pneumocystis carinii dihydrofolate reductase complexes with folate and NADP+. Biochemistry 38 4303–4312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dengler, U., Niefind, K., Kiess, M., and Schomburg, D. 1997. Crystal structure of a ternary complex of D-2-hydroxyisocaproate dehydrogenase from Lactobacillus casei, NAD+ and 2-oxoisocaproate at 1.9 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 267 640–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessen, A., Quemard, A., Blanchard, J.S., Jacobs, W.R., Jr., and Sacchettini, J.C. 1995. Crystal structure and function of the isoniazid target of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 267 1638–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobritzsch, D., Schneider, G., Schnackerz, K.D., and Lindqvist, Y. 2001. Crystal structure of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, a major determinant of the pharmacokinetics of the anti-cancer drug 5-fluorouracil. EMBO J. 20 650–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duee, E., Olivier-Deyris, L., Fanchon, E., Corbier, C., Branlant, G., and Dideberg, O. 1996. Comparison of the structures of wild-type and a N313T mutant of Escherichia coli glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenases: Implication for NAD binding and cooperativity. J. Mol. Biol. 257 814–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, C.R., Banfield, M.J., Barker, J.J., Higham, C.W., Moreton, K.M., Turgut-Balik, D., Brady, R.L., and Holbrook, J.J. 1996. The structure of lactate dehydrogenase from Plasmodium falciparum reveals a new target for anti-malarial design. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3 912–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenbrenner, M., Chlumsky, L.J., Khanna, P., Strasser, F., and Jorns, M.S. 2001. Organization of the multiple coenzymes and subunits and role of the covalent flavin link in the complex heterotetrameric sarcosine oxidase. Biochemistry 40 5352–5367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faig, M., Bianchet, M.A., Talalay, P., Chen, S., Winski, S., Ross, D., and Amzel, L.M. 2000. Structures of recombinant human and mouse NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductases: Species comparison and structural changes with substrate binding and release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97 3177–3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faig, M., Bianchet, M.A., Winski, S., Hargreaves, R., Moody, C.J., Hudnott, A.R., Ross, D., and Amzel, L.M. 2001. Structure-based development of anticancer drugs: Complexes of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 with chemotherapeutic quinones. Structure (Camb.) 9 659–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchetti, P., Cappellacci, L., Perlini, P., Jayaram, H.N., Butler, A., Schneider, B.P., Collart, F.R., Huberman, E., and Grifantini, M. 1998. Isosteric analogues of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide derived from furanfurin, thiophenfurin, and selenophenfurin as mammalian inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (type I and II) inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 41 1702–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason, W.B., Fu, Z., Birktoft, J., and Banaszak, L. 1994. Refined crystal structure of mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase from porcine heart and the consensus structure for dicarboxylic acid oxidoreductases. Biochemistry 33 2078–2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourley, D.G., Schuttelkopf, A.W., Leonard, G.A., Luba, J., Hardy, L.W., Beverley, S.M., and Hunter, W.N. 2001. Pteridine reductase mechanism correlates pterin metabolism with drug resistance in trypanosomatid parasites. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 521–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, M.D. and Banaszak, L.J. 1993. Crystal structure of a ternary complex of Escherichia coli malate dehydrogenase citrate and NAD at 1.9 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 232 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegeman, A.D., Gross, J.W., and Frey, P.A. 2001. Probing catalysis by Escherichia coli dTDP-glucose-4,6-dehydratase: Identification and preliminary characterization of functional amino acid residues at the active site. Biochemistry 40 6598–6610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horer, S., Stoop, J., Mooibroek, H., Baumann, U., and Sassoon, J. 2001. The crystallographic structure of the mannitol 2-dehydrogenase NADP+ binary complex from Agaricus bisporus. J. Biol. Chem. 276 27555–27561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janin, J. 1999. Wet and dry interfaces: The role of solvent in protein–protein and protein–DNA recognition. Struct. Fold. Des. 7 R277–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, G.A. 1997. An introduction to hydrogen bonding. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Jones, T.A., Zou, J.Y., Cowan, S.W., and Kjeldgaard. 1991. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A 47 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karplus, P.A. and Schulz, G.E. 1987. Refined structure of glutathione reductase at 1.54 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 195 701–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1989. Substrate binding and catalysis by glutathione reductase as derived from refined enzyme: Substrate crystal structures at 2 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 210 163–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, C.A., Nishiyama, M., Ohnishi, Y., Beppu, T., and Birktoft, J.J. 1993. Determinants of protein thermostability observed in the 1.9-Å crystal structure of malate dehydrogenase from the thermophilic bacterium Thermus flavus. Biochemistry 32 3913–3922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno, Y., Natsumeda, Y., Nagai, M., Yamaji, Y., Ohno, S., Suzuki, K., and Weber, G. 1991. Expression of human IMP dehydrogenase types I and II in Escherichia coli and distribution in human normal lymphocytes and leukemic cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 266 506–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkhin, Y., Kalb, A.J., Peretz, M., Bogin, O., Burstein, Y., and Frolow, F. 1998. NADP-dependent bacterial alcohol dehydrogenases: Crystal structure, cofactor-binding and cofactor specificity of the ADHs of Clostridium beijerinckii and Thermoanaerobacter brockii. J. Mol. Biol. 278 967–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis, P.J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Lamzin, V.S., Dauter, Z., Popov, V.O., Harutyunyan, E.H., and Wilson, K.S. 1994. High resolution structures of holo and apo formate dehydrogenase. J. Mol. Biol. 236 759–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.I., Chang, C., Cho, S.J., Eom, S.H., Kim, K.K., Yu, Y.G., and Suh, S.W. 2001. Crystal structure of the MJ0490 gene product of the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Methanococcus jannaschii, a novel member of the lactate/malate family of dehydrogenases. J. Mol. Biol. 307 1351–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesk, A.M. 1995. NAD-binding domains of dehydrogenases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 5 775–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Vrielink, A., Brick, P., and Blow, D.M. 1993. Crystal structure of cholesterol oxidase complexed with a steroid substrate: Implications for flavin adenine dinucleotide dependent alcohol oxidases. Biochemistry 32 11507–11515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, R., Sirawaraporn, R., Chitnumsub, P., Sirawaraporn, W., Wooden, J., Athappilly, F., Turley, S., and Hol, W.G. 2000. Three-dimensional structure of M. tuberculosis dihydrofolate reductase reveals opportunities for the design of novel tuberculosis drugs. J. Mol. Biol. 295 307–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao, D.I., Thompson, J.E., Fahnestock, S., Valent, B., and Jordan, D.B. 2001. A structural account of substrate and inhibitor specificity differences between two naphthol reductases. Biochemistry 40 8696–8704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likic, V.A., Juranic, N., Macura, S., and Prendergast, F.G. 2000. A "structural" water molecule in the family of fatty acid binding proteins. Protein Sci. 9 497–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscombe, N.M., Laskowski, R.A., and Thornton, J.M. 2001. Amino acid-base interactions: A three-dimensional analysis of protein–DNA interactions at an atomic level. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 2860–2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrone, T.J., Briggs, J.M., and McCammon, J.A. 1997. Structure-based drug design: Computational advances. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 37 71–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martz, E. 2001. "Protein explorer software," http://proteinexplorer.org. For a list of further references, see http://molvis.sdsc.edu/protexpl/pe_lit.htm.

- Mattevi, A., Tedeschi, G., Bacchella, L., Coda, A., Negri, A., and Ronchi, S. 1999. Structure of L-aspartate oxidase: Implications for the succinate dehydrogenase/fumarate reductase oxidoreductase family. Struct. Fold. Des. 7 745–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, D.A., Bolin, J.T., Burridge, J.M., Filman, D.J., Volz, K.W., Kaufman, B.T., Beddell, C.R., Champness, J.N., Stammers, D.K., and Kraut, J. 1985. Refined crystal structures of Escherichia coli and chicken liver dihydrofolate reductase containing bound trimethoprim. J. Biol. Chem. 260 381–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijers, R., Morris, R.J., Adolph, H.W., Merli, A., Lamzin, V.S., and Cedergren-Zeppezauer, E.S. 2001. On the enzymatic activation of NADH. J. Biol. Chem. 276 9316–9321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, E.A. and Bacon, D.J. 1997. Raster3D photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 277 505–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittl, P.R. and Schulz, G.E. 1994. Structure of glutathione reductase from Escherichia coli at 1.86 Å resolution: Comparison with the enzyme from human erythrocytes. Protein Sci. 3 799–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulichak, A.M., Theisen, M.J., Essigmann, B., Benning, C., and Garavito, R.M. 1999. Crystal structure of SQD1, an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of the plant sulfolipid headgroup donor UDP-sulfoquinovose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96 13097–13102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murzin, A.G., Brenner, S.E., Hubbard, T., and Chothia, C. 1995. SCOP: A structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J. Mol. Biol. 247 536–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai, M., Natsumeda, Y., Konno, Y., Hoffman, R., Irino, S., and Weber, G. 1991. Selective up-regulation of type II inosine 5`-monophosphate dehydrogenase messenger RNA expression in human leukemias. Cancer Res. 51 3886–3890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiya, Y. and Imanaka, T. 1996. Analysis of interaction between the Arthrobacter sarcosine oxidase and the coenzyme flavin adenine dinucleotide by site-directed mutagenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62 2405–2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otagiri, M., Kurisu, G., Ui, S., Takusagawa, Y., Ohkuma, M., Kudo, T., and Kusunoki, M. 2001. Crystal structure of meso-2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase in a complex with NAD+ and inhibitor mercaptoethanol at 1.7 Å resolution for understanding of chiral substrate recognition mechanisms. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 129 205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantano, S., Alber, F., Lamba, D., and Carloni, P. 2002. NADH interactions with WT- and S94A-acyl carrier protein reductase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: An ab initio study. Proteins 47 62–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, P.J., Macedo-Ribeiro, S., Parraga, A., Perez-Luque, R., Cunningham, O., Darcy, K., Mantle, T.J., and Coll, M. 2001. Structure of human biliverdin IXβ reductase, an early fetal bilirubin IXβ producing enzyme. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poornima, C.S. and Dean, P.M. 1995. Hydration in drug design. 3. Conserved water molecules at the ligand-binding sites of homologous proteins. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 9 521–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell, A.J., Read, J.A., Banfield, M.J., Gunn-Moore, F., Yan, S.D., Lustbader, J., Stern, A.R., Stern, D.M., and Brady, R.L. 2000. Recognition of structurally diverse substrates by type II 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (HADH II)/amyloid-beta binding alcohol dehydrogenase (ABAD). J. Mol. Biol. 303 311–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, G.S., Sridhar, V., Yamaguchi, M., Hatefi, Y., and Stout, C.D. 1999. Crystal structure of transhydrogenase domain III at 1.2 Å resolution. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6 1126–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty, J.B., Simon, J.W., Baldock, C., Artymiuk, P.J., Baker, P.J., Stuitje, A.R., Slabas, A.R., and Rice, D.W. 1995. Common themes in redox chemistry emerge from the X-ray structure of oilseed rape (Brassica napus) enoyl acyl carrier protein reductase. Structure 3 927–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymer, M.L., Sanschagrin, P.C., Punch, W.F., Venkataraman, S., Goodman, E.D., and Kuhn, L.A. 1997. Predicting conserved water-mediated and polar ligand interactions in proteins using a K-nearest-neighbors genetic algorithm. J. Mol. Biol. 265 445–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescigno, M. and Perham, R.N. 1994. Structure of the NADPH-binding motif of glutathione reductase: Efficiency determined by evolution. Biochemistry 33 5721–5727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosano, C., Bisso, A., Izzo, G., Tonetti, M., Sturla, L., De Flora, A., and Bolognesi, M. 2000. Probing the catalytic mechanism of GDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-mannose Epimerase/Reductase by kinetic and crystallographic characterization of site-specific mutants. J. Mol. Biol. 303 77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmann, M.G., Moras, D., and Olsen, K.W. 1974. Chemical and biological evolution of a nucleotide-binding protein. Nature 250 194–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roujeinikova, A., Levy, C.W., Rowsell, S., Sedelnikova, S., Baker, P.J., Minshull, C.A., Mistry, A., Colls, J.G., Camble, R., Stuitje, A.R., Slabas, A.R., Rafferty, J.R., Pauptit, R.A., Viner, R., and Rice, D.W. 1999. Crystallographic analysis of triclosan bound to enoyl reductase. J. Mol. Biol. 294 527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saridakis, V., Christendat, D., Kimber, M.S., Dharamsi, A., Edwards, A.M., and Pai, E.F. 2001. Insights into ligand binding and catalysis of a central step in NAD+ synthesis: Structures of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum NMN adenylyltransferase complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 276 7225–7232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya, M.R. and Kraut, J. 1997. Loop and subdomain movements in the mechanism of Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase: Crystallographic evidence. Biochemistry 36 586–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiner, S., Kar, T., and Gu, Y. 2001. Strength of the CαH..O hydrogen bond of amino acid residues. J. Biol. Chem. 276 9832–9837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreuder, H.A., Prick, P.A., Wierenga, R.K., Vriend, G., Wilson, K.S., Hol, W.G., and Drenth, J. 1989. Crystal structure of the p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase-substrate complex refined at 1.9 A resolution. Analysis of the enzyme–substrate and enzyme–product complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 208 679–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultze, P. and Feigon, J. 1997. Chirality errors in nucleic acid structures. Nature 387 668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarzynski, T., Moody, P.C., and Wonacott, A.J. 1987. Structure of holo-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from Bacillus stearothermophilus at 1.8 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 193 171–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.E. and Tanner, J.J. 1999. Molecular dynamics simulations of NAD+ in solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 8637–8644. [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2000. Conformations of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) in various environments. J. Mol. Recognit. 13 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreenivasan, U. and Axelsen, P.H. 1992. Buried water in homologous serine proteases. Biochemistry 31 12785–12791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, M.J., Parikh, S., Xiao, G., Tonge, P.J., and Kisker, C. 1999. Structural basis and mechanism of enoyl reductase inhibition by triclosan. J. Mol. Biol. 290 859–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland, C.L. and Karplus, P.A. 1995. Overexpression of Crithidia fasciculata trypanothione reductase and crystallization using a novel geometry. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 51 337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, N., Nonaka, T., Nakanishi, M., Deyashiki, Y., Hara, A., and Mitsui, Y. 1996a. Crystal structure of the ternary complex of mouse lung carbonyl reductase at 1.8 Å resolution: The structural origin of coenzyme specificity in the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family. Structure 4 33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, N., Nonaka, T., Tanabe, T., Yoshimoto, T., Tsuru, D., and Mitsui, Y. 1996b. Crystal structures of the binary and ternary complexes of 7α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 35 7715–7730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P., Pealing, S.L., Reid, G.A., Chapman, S.K., and Walkinshaw, M.D. 1999. Structural and mechanistic mapping of a unique fumarate reductase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6 1108–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoden, J.B., Frey, P.A., and Holden, H.M. 1996a. Crystal structures of the oxidized and reduced forms of UDP-galactose 4-epimerase isolated from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 35 2557–2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1996b. High-resolution X-ray structure of UDP-galactose 4-epimerase complexed with UDP-phenol. Protein Sci. 5 2149–2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1996c. Molecular structure of the NADH/UDP-glucose abortive complex of UDP-galactose 4-epimerase from Escherichia coli: Implications for the catalytic mechanism. Biochemistry 35 5137–5144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoden, J.B., Hegeman, A.D., Wesenberg, G., Chapeau, M.C., Frey, P.A., and Holden, H.M. 1997. Structural analysis of UDP-sugar binding to UDP-galactose 4-epimerase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 36 6294–6304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoden, J.B., Wohlers, T.M., Fridovich-Keil, J.L., and Holden, H.M. 2000. Crystallographic evidence for Tyr 157 functioning as the active site base in human UDP-galactose 4-epimerase. Biochemistry 39 5691–5701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2001. Human UDP-galactose 4-epimerase. Accommodation of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine within the active site. J. Biol. Chem. 276 15131–15136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umhau, S., Pollegioni, L., Molla, G., Diederichs, K., Welte, W., Pilone, M.S., and Ghisla, S. 2000. The X-ray structure of D-amino acid oxidase at very high resolution identifies the chemical mechanism of flavin-dependent substrate dehydrogenation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97 12463–12468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Calenbergh, S., Verlinde, C.L., Soenens, J., De Bruyn, A., Callens, M., Blaton, N.M., Peeters, O.M., Rozenski, J., Hol, W.G., and Herdewijn, P. 1995. Synthesis and structure–activity relationships of analogs of 2`-deoxy-2`-(3-methoxybenzamido)adenosine, a selective inhibitor of trypanosomal glycosomal glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. J. Med. Chem. 38 3838–3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Grunsven, E.G., van Berkel, E., Ijlst, L., Vreken, P., de Klerk, J.B., Adamski, J., Lemonde, H., Clayton, P.T., Cuebas, D.A., and Wanders, R.J. 1998. Peroxisomal D-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency: Resolution of the enzyme defect and its molecular basis in bifunctional protein deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95 2128–2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhooke, J.L., Thoden, J.B., Brunhuber, N.M., Blanchard, J.S., and Holden, H.M. 1999. Phenylalanine dehydrogenase from Rhodococcus sp. M4: High-resolution X-ray analyses of inhibitory ternary complexes reveal key features in the oxidative deamination mechanism. Biochemistry 38 2326–2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verlinde, C.L., Callens, M., Van Calenbergh, S., Van Aerschot, A., Herdewijn, P., Hannaert, V., Michels, P.A., Opperdoes, F.R., and Hol, W.G. 1994. Selective inhibition of trypanosomal glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase by protein structure-based design: Toward new drugs for the treatment of sleeping sickness. J. Med. Chem. 37 3605–3613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verlinde, C.L.M.J. and Hol, W.G.J. 1994. Structure-based drug design: Progress, results and challenges. Structure 2 577–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, M.A., Trickey, P., Chen, Z.W., Mathews, F.S., and Jorns, M.S. 2000. Monomeric sarcosine oxidase: 1. Flavin reactivity and active site binding determinants. Biochemistry 39 8813–8824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward, W.H., Holdgate, G.A., Rowsell, S., McLean, E.G., Pauptit, R.A., Clayton, E., Nichols, W.W., Colls, J.G., Minshull, C.A., Jude, D.A., Mistry, A., Timms, D, Camble, R., Hales, N.J., Britton, C.J., and Taylor, I.W. 1999. Kinetic and structural characteristics of the inhibition of enoyl (acyl carrier protein) reductase by triclosan. Biochemistry 38 12514–12525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warkentin, E., Mamat, B., Sordel-Klippert, M., Wicke, M., Thauer, R.K., Iwata, M., Iwata, S., Ermler, U., and Shima, S. 2001. Structures of F420H2:NADP+ oxidoreductase with and without its substrates bound. EMBO J. 20 6561–6569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlow, M., Howard, A.J., Stewart, D., Hardman, K.D., Chan, J.H., Baccanari, D.P., Tansik, R.L., Hong, J.S., and Kuyper, L.F. 2001. X-Ray crystal structures of Candida albicans dihydrofolate reductase: High resolution ternary complexes in which the dihydronicotinamide moiety of NADPH is displaced by an inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 44 2928–2932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlow, M., Howard, A.J., Stewart, D., Hardman, K.D., Kuyper, L.F., Baccanari, D.P., Fling, M.E., and Tansik, R.L. 1997. X-ray crystallographic studies of Candida albicans dihydrofolate reductase. High resolution structures of the holoenzyme and an inhibited ternary complex. J. Biol. Chem. 272 30289–30298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierenga, R.K., De Maeyer, M.C.H., and Hol, W.G.J. 1985. Interaction of pyrophosphate moieties with α-helixes in dinucleotide binding proteins. Biochemistry 24 1346–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Winski, S.L., Faig, M., Bianchet, M.A., Siegel, D., Swann, E., Fung, K., Duncan, M.W., Moody, C.J., Amzel, L.M., and Ross, D. 2001. Characterization of a mechanism-based inhibitor of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 by biochemical, X-ray crystallographic, and mass spectrometric approaches. Biochemistry 40 15135–15142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfahrt, G., Witt, S., Hendle, J., Schomburg, D., Kalisz, H.M., and Hecht, H.J. 1999. 1.8 and 1.9 Å resolution structures of the Penicillium amagasakiense and Aspergillus niger glucose oxidases as a basis for modelling substrate complexes. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55 969–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, K., Kurisu, G., Kusunoki, M., Tabata, S., Urabe, I., and Osaki, S. 2001. Crystal structure of glucose dehydrogenase from Bacillus megaterium IWG3 at 1.7 Å resolution. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 129 303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, A., Kato, H., Wakatsuki, S., Tomizaki, T., Nakatsu, T., Nakajima, K., Hashimoto, T., Yamada, Y., and Oda, J. 1999. Structure of tropinone reductase-II complexed with NADP+ and pseudotropine at 1.9 Å resolution: Implication for stereospecific substrate binding and catalysis. Biochemistry 38 7630–7637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Q.K., Kass, I.J., Sampson, N.S., and Vrielink, A. 1999. Crystal structure determination of cholesterol oxidase from Streptomyces and structural characterization of key active site mutants. Biochemistry 38 4277–4286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zens, A.P., Bryson, T.A., Dunlap, R.B., Fisher, R.R., and Ellis, P.D. 1976. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of pyridine dinucleotides.7.1 The solution conformational dynamics of the adenosine portion of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and other related purine containing compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 98 7559–7564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J., Martasek, P., Paschke, R., Shea, T., Siler Masters, B.S., and Kim, J.J. 2001. Crystal structure of the FAD/NADPH-binding domain of rat neuronal nitric-oxide synthase. Comparisons with NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase. J. Biol. Chem. 276 37506–37513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.-g., Evans, G., Rotella, F.J., Westbrook, E.M., Beno, D., Huberman, E., Joachimiak, A., and Collart, F.R. 1999. Characteristics and crystal structure of bacterial inosine-5`-monophosphate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 38 4691–4700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, G.A. and Schulz, G.E. 2000. Crystal structures of adrenodoxin reductase in complex with NADP+ and NADPH suggesting a mechanism for the electron transfer of an enzyme family. Biochemistry 39 10986–10995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, G.A., Vonrhein, C., Hanukoglu, I., and Schulz, G.E. 1999. The structure of adrenodoxin reductase of mitochondrial P450 systems: Electron transfer for steroid biosynthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 289 981–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]