Abstract

Integrins are composed of noncovalently bound dimers of an α- and a β-subunit. They play an important role in cell-matrix adhesion and signal transduction through the cell membrane. Signal transduction can be initiated by the binding of intracellular proteins to the integrin. Binding leads to a major conformational change. The change is passed on to the extracellular domain through the membrane. The affinity of the extracellular domain to certain ligands increases; thus at least two states exist, a low-affinity and a high-affinity state. The conformations and conformational changes of the transmembrane (TM) domain are the focus of our interest. We show by a global search of helix–helix interactions that the TM section of the family of integrins are capable of adopting a structure similar to the structure of the homodimeric TM protein Glycophorin A. For the αIIbβ3 integrin, this structural motif represents the high-affinity state. A second conformation of the TM domain of αIIbβ3 is identified as the low-affinity state by known mutational and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies. A transition between these two states was determined by molecular dynamics (MD) calculations. On the basis of these calculations, we propose a three-state mechanism.

Keywords: Signal transduction, molecular modeling, integrin, glycophorin A, transmembrane

Information transmission through the cell membrane is mediated by membrane-spanning receptors. Most receptors transmit signals by conformational changes. However, the conformational changes involved in most signaling events is poorly understood (Ottemann et al. 1999).

One family of transmembrane (TM) receptors is the family of integrins. Integrins are known to play an important role in cell-matrix adhesion and signal transduction through the cell membrane. They form noncovalently bound heterodimers between α- and β-subunits. Each monomer is composed of a large extracellular domain, one TM domain, and a short cytoplasmic tail (Humphries 2000).

Through two mechanisms, termed inside-out and outside-in signaling, cellular events control the affinity of integrins for ligands. In inside-out signaling, the binding of certain factors to the intracellular domain of the integrin leads to a conformational change that alters the relative orientation of the two monomers to each other (Hantgan et al. 1999; Emsley et al. 2000; Humphries 2000; Liddington and Bankston 2000). A signal is transduced through the cell membrane by which the integrin's affinity for extracellular ligands increases. The integrin is thus switched from a low-affinity, or closed state to a high-affinity, or open state following a conformational change. In outside-in signaling, binding of ligands in the extracellular matrix is followed by integrin clustering that triggers a cascade of intracellular events such as attachment to the cytoskeleton (Du et al. 1993; Leisner et al. 1999; Levy-Toledano 1999). The importance of the cytoplasmic domain for inside-out signaling, as well as the extracellular domains of integrins, has been the focus of many studies (Dedhar and Hannigan 1996; Hemler 1998; Green and Humphries 1999; Liu et al. 2000). However, the TM domains of integrins have not been studied to a similar extent.

The structure of the cytoplasmic domain of αIIb has been solved by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (Hwang and Vogel 2000; Vinogradova et al. 2000). Also the X-ray structure of a complex of the I domain of integrin α2β1 and a collagen triple helix has been solved, indicating a basis for affinity regulation and signal transduction (Emsley et al. 2000). The X-ray structure of the extracellular domain of αVβ3 has also been published (Xiong et al. 2001), giving input for future work on a full model of αIIbβ3.

We are interested in the structural features of the TM domain of integrins and have focused our efforts primarily on the αIIbβ3 integrin subtype. Experimental difficulties make structural and functional studies on TM processes rare. Computational methods like those we have used are ideally suited to fill the void of information about the structure and dynamics of TM domains (Adams et al. 1995; Adams and Brunger 1997; Durell et al. 1998; Sansom 1998; Sansom and Davison 2000).

The TM domain is thought to be important for integrin dimerization and subsequent signaling. Although it is known that integrins can also dimerize when neither the intracellular nor the TM domain is present, the dimerization efficiency of the deletion mutants is reduced (Frachet 1992). A recombinant soluble form of integrin αIIbβ3, lacking the cytoplasmic and TM domain, assumes an active, ligand-binding conformation, whereas the ground state of the wild-type protein is a low-affinity state (Peterson et al. 1998). Although two model constructs, one lacking the extracellular and TM domains (Ulmer et al. 2001), the other including the TM domains (Li et al. 2001), failed to directly show by NMR studies subunit interactions, a vast number of biochemical investigations of the whole protein in the membrane support interactions of at least the cytosolic, membrane proximal parts of integrins. It therefore seems likely that the TM and cytoplasmic part are also involved in the dimerization and signal transduction process. The failure to show directly these interactions is likely to be a consequence of the model constructs. In the work of Ulmer et al., the TM domains were substituted by a helical coiled-coil construct. In the context of this construct, no regular secondary structure could be observed for either subunit. Another NMR study (Vinogradova et al. 2000) focused on the cytoplasmic domain of αIIb and showed that associated to a membrane mimetic the cytoplasmic domain of αIIb forms an α-helix with a nonhelical tail. Thus the structure-inducing effect of the membrane seems to be important. The work of Li et al. used a construct including the TM parts. The failure to detect subunit interactions might rather stem from the use of dodecyl phosphocholine as a membrane mimetic. Membrane mimetics can easily disrupt subunit association because of rather strong helix–micelle interactions and curvature of the micelles. A well-suited tool for studying the interactions in a membrane-like environment would thus be solid-state NMR. It has been very elegantly shown by protein engineering studies that the membrane proximal parts of αIIbβ3 interact and inactivate the integrin (Lu et al. 2001). Furthermore, it was shown that a salt bridge between the subunits was formed, implying close association near the membrane (Hughes et al. 1996). By mass spectroscopy, terbium luminescence, and surface plasmon resonance, interactions between the membrane proximal parts have been illustrated (Haas and Plow 1996; Vallar et al. 1999). In addition, several diseases are connected to mutations in the TM domain of integrins, again pointing toward an active involvement of the TM domain in the dimerization and transduction process (Scott et al. 1998).

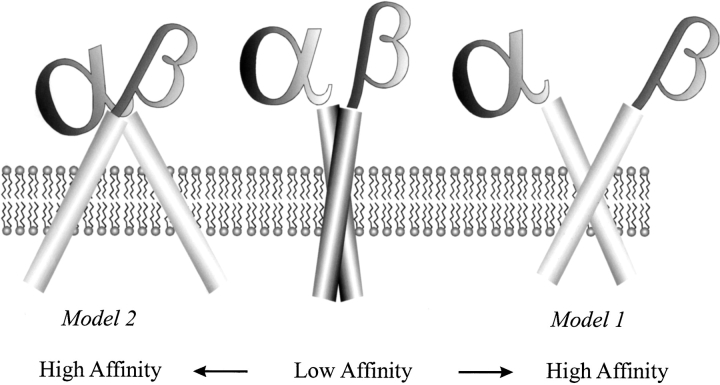

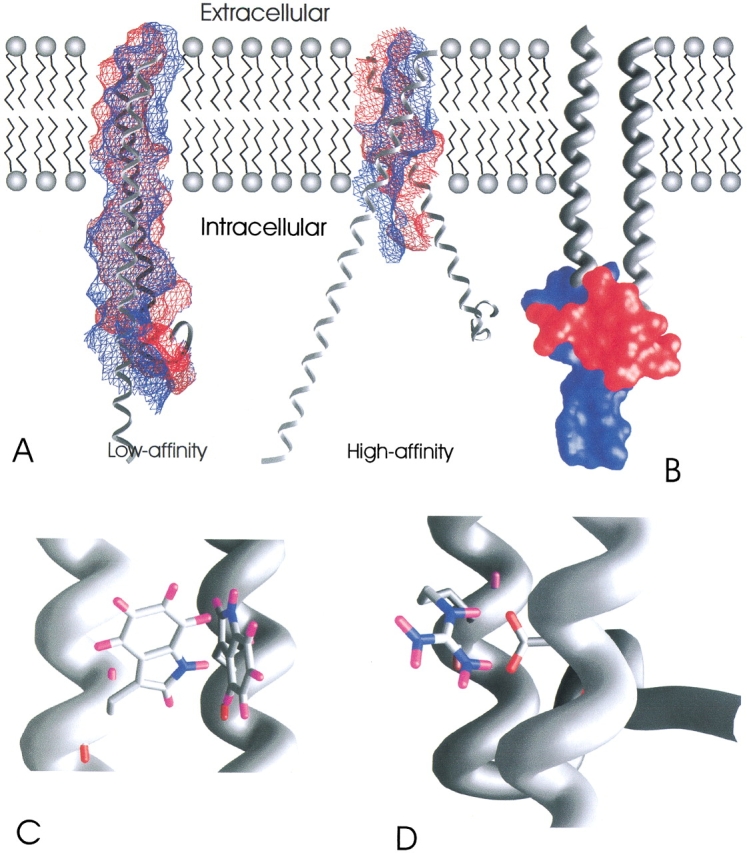

There are two models of TM signal transduction supported by electron microscopy and biochemical data (Fig. 1 ▶) (Hantgan et al. 1999; Plow et al. 2000; Takagi et al. 2001). The models agree that a scissor-like movement takes place after ligand binding and that this movement separates the cytoplasmic region as well as the extracellular stalks. The models differ in the position of the hinge region: Whereas model one places the hinge region in the TM part, model two proposes a hinge region close to the extracellular binding site.

Fig. 1.

Models of signal transduction: Two models for signal transduction by integrins are proposed in the literature. Although in model one the transmembrane (TM) parts of the integrin subunits stay associated, in model two the hinge region is closer to the extracellular headgroup and the TM region gets separated. Because of the high viscosity of the membrane, a much higher activation energy would be necessary for a signal transduction process according to model two. In model one the transition can furthermore be facilitated by increased TM interactions in the high-affinity conformation.

Our studies support model one and show that the large conformational changes necessary to transmit a signal over a large distance are possible with comparably small changes in the TM domain. Model two implies that ligand binding also separates the TM region, whereas in model one the TM helices stay associated. The large separation of the TM domains required by model two would be kinetically unfavorable because of the high viscosity of the membrane. Furthermore, model two is based on studies with integrins lacking the TM domain so that important structural restraints are not present, possibly affecting the validity of the model. Contacts between the TM parts of the protein can stabilize the high-affinity conformation and reduce the energetic cost of the transition in model one. If the interaction between the helices is stronger in the high-affinity, or open, conformation, this energy gain could partially compensate for the energy loss from lost interactions in the intracellular and extracellular domains.

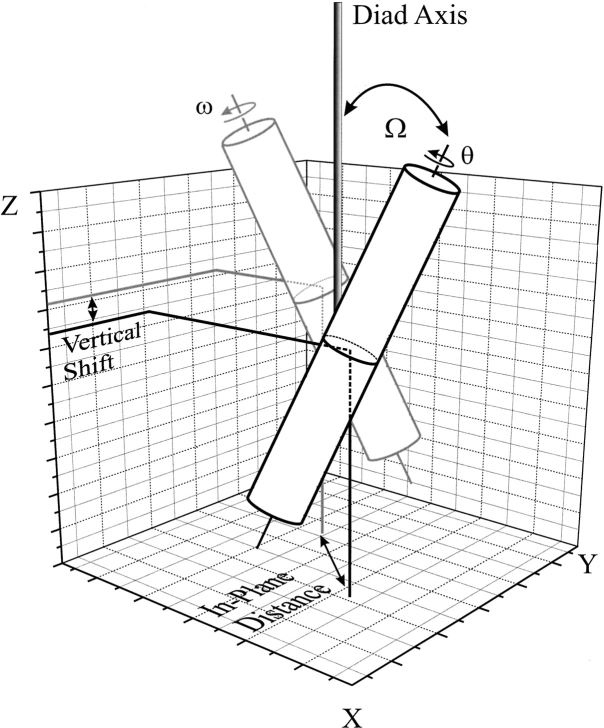

A global search of helix–helix interactions has been shown to be a valuable tool for the prediction of TM helix conformations (Adams et al. 1995; Adams et al. 1996; Adams and Brunger 1997). In this procedure the structural parameters of a helix-dimer are varied in a systematic fashion to optimize helix–helix packing. The structural parameters of a helix dimer are shown in Figure 2 ▶. Because of the high number of degrees of freedom and inaccuracies of the force fields, no unique solution can be found with such a procedure. A search results in more than one low-energy structure per helix pair with comparable interaction energies. Thus the energies alone cannot serve as the discriminatory function between the clusters. Experimental data or other ways of discriminating between the clusters have to be included. It has been shown recently (Briggs et al. 2001) that a parallel search of homologous sequences can serve to identify low-energy structures that are conserved among the sequences, and that these conserved structures relate to the native structure of the protein.

Fig. 2.

Degrees of freedom of a helix pair. Structural degrees of freedom for a helix pair in a membrane environment: During the global conformational search of helix–helix interactions, the initial vertical shift was set to zero and the initial crossing angle Ω to either 25° or −25°. During the simulations all parameters were free to vary, and the maximum distance between the centers of the helices was set to 10.4 Å.

Here we combine experimental information and evolutionary conservation to identify the TM conformations of αIIbβ3. We performed independent global searches of helix–helix interactions for 16 different subunit combinations of integrins. The combinations tested are shown in Table 1. On the basis of the global search and molecular dynamics (MD) calculations, we present a complete description of an integrin signaling. Our data show that integrins can form GpA-like TM conformations. For the experimentally well-characterized integrin subtype αIIbβ3, this conformation represents the high-affinity or open conformation according to our model. In addition, we have identified a model for the low-affinity or closed conformation. The transition between the two conformations is elucidated by MD calculations. Our model of signaling involves a combination of a rotation and a scissor-like movement, leading to substantial changes of the integrin conformation.

Table 1.

Integrin subunit association

| β1 | β2 | β3 | β5 | β6 | β7 | β8 | |

| α1 | X | ||||||

| α2 | X | ||||||

| α3 | X | ||||||

| α4 | X | ||||||

| α5 | X | ||||||

| α6 | X | ||||||

| α7 | X | ||||||

| αD | X | ||||||

| αL | X | ||||||

| αM | X | ||||||

| αV | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| αIIb | X |

The combinations marked with an X were subject to a global conformational search.

Results and Discussion

Global search and structural conservation

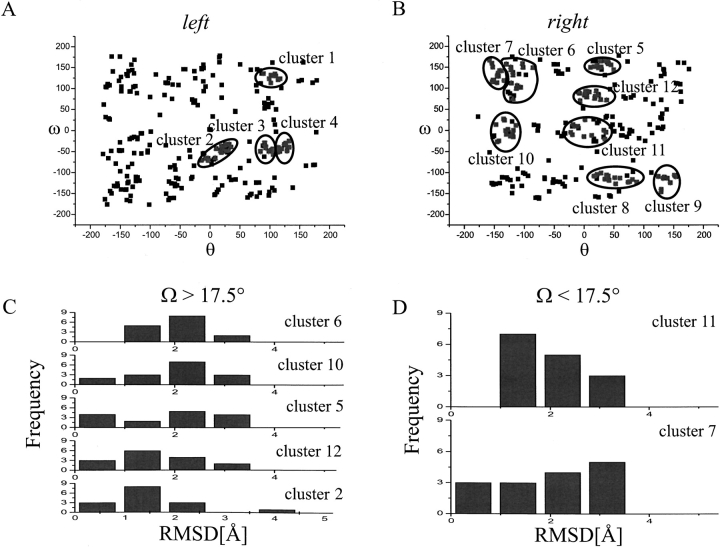

We chose to focus on αIIbb3 integrin subtype because it has been studied extensively and using experimental results allows us to verify our computational predictions. We performed a global conformational search of helix–helix interactions for αIIbβ3, as well as for 15 other subtype combinations as denoted in Table 1. For αIIbβ3, the search resulted in 12 clusters (Fig. 3 A,B ▶). These clusters were compared with the clusters of the other subtypes to detect structural conservation among the integrin types (Table 2). Seven of the 12 clusters displayed an average root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) to clusters from other subtype searches of ≤2 Å. These seven were divided into two groups: one group comprising clusters with a crossing angle larger than 17.5° as candidates for the high-affinity conformation and the other group comprising clusters with crossing angles smaller than 17.5° as candidates for the low-affinity conformation. The RMSD distributions for the groups are shown in Figure 3 C and D ▶. Although cluster 2 has the lowest average RMSD of 1.6 Å, it is not conserved among all integrins. α5β1 does not form a similar structure; the most similar cluster has an RMSD of 4.0 Å to cluster 2. Cluster 12, on the other hand, has an average RMSD to the other subtypes of 1.7 Å, only slightly higher than cluster 2. The highest RMSD to any other subtype is 2.8 Å to αvβ8, thus significantly smaller than the 4.0 Å of cluster 2 to α5β1. αvβ8 integrin adopts a structure with a hydrogen bond between the side-chain hydroxyl moiety of a 693Thr from β8 at an interfacial residue that corresponds to a 725Ser in β3 and the main chain of the other helix. This might be an artifact of the calculations in vacuo. Thus it seems as if cluster 12 is better conserved among the integrins than cluster 2, despite the higher average RMSD. Cluster 5 is also highly conserved, although the RMSDs are shifted to higher values (Fig. 3C ▶; Table 2). Clusters 10 and 6 are significantly less conserved.

Fig. 3.

Upper panel: Distribution of final ω/θ rotation angles. (A) Distribution of rotation angles for all structures obtained by simulated annealing with a left-handed crossing angle. The rotation angle combinations that form the clusters as described in Materials and Methods are shown in grey and circled. (B) Distribution of rotation angles for all structures obtained by simulated annealing with a right-handed crossing angle. Lower panel: Histogram of root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of αIIbβ3 clusters to clusters from other subtypes. (C) Distribution of RMSD values for αIIbβ3 clusters with a crossing angle of Ω > 17.5°; whereas cluster 2 has the smallest RMSD average, one subtype does not form such a structure. The distribution of cluster 12 is very similar, but here all subtypes tested can form similar structures. For cluster 5 the RMSDs are shifted to higher values, even more so for cluster 10 and cluster 6. (D) αIIbβ3 clusters with a crossing angle of Ω < 17.5°; both clusters are structurally conserved to a similar degree, with cluster 7 showing a higher spread in RMSD values.

Table 2.

Minimum RMSD of the clusters of the other tested subtype combinations with respect to the 12 clusters of αIIbβ3 in Å

| Cluster | ||||||||||||

| Integrin | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| α1β1 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 0.9 | 2.8 | 0.7 |

| αLβ2 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 1.8 | 0.7 |

| αMβ2 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 2.1 |

| αvβ3 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 0.6 |

| α4β7 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 0.9 |

| αvβ8 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| α2β1 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 1.3 |

| α3β1 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 2.4 |

| α5β1 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| α6β1 | 3.5 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 2.5 |

| α7β1 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 1.7 |

| αdβ2 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.7 |

| αvβ1 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 1.6 |

| αvβ5 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 2.5 |

| αvβ6 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Mean RMSD | 2.8 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| Ω(αIIbβ3) | 23.2 | 18.7 | 19.3 | 22.2 | −28.6 | −23.8 | −12.3 | −27.9 | −19.8 | −21.8 | −14.6 | −24.3 |

The average RMSD for each cluster and the crossing angle of αIIbβ3 are also shown.

RMSD, root-mean-square deviation.

Only two clusters have a crossing angle lower than 17.5°. These two clusters, cluster 7 and cluster 11, are conserved to a similar degree with average RMSDs to the other subtypes of 1.9 Å and 2.0 Å, respectively. Cluster 11 appears to be better conserved: No subtype has an RMSD above 3.0 Å, whereas for cluster 7 three subtypes have an RMSD of 3.0 Å or higher.

The low affinity conformation of αIIbβ3 integrin

To compare experimental results with our computational model, certain assumptions have to be made about the conformational nature of the cytosolic and extracellular parts of αIIbβ3. The stalk region can be assumed to be approximately linear, rigid, and oriented in a similar direction as the TM helices on the basis of electron microscopy and other studies (Hantgan et al. 1999; Humphries 2000). The X-ray structure of the extracellular domain of αVβ3 also shows linear stalk regions, although a kink close to the headgroups of the integrin is formed (Xiong et al. 2001). This kink is not in agreement with electron microscopy studies and might be a crystallization artifact. The structure of the cytosolic domain of αIIb has been solved by NMR in 45% polytetrafluoroethylene (Hwang and Vogel 2000), as well as associated to a micelle (Vinogradova et al. 2000). For our studies, we chose the structure of the cytoplasmic domain of αIIb associated to a micelle because here the structure-inducing effect of the membrane is mimicked. Furthermore, the structure of a constitutively active mutant was solved under this condition. The cytosolic αIIb-domain is a continuation of the TM helix with a nonhelical tail.

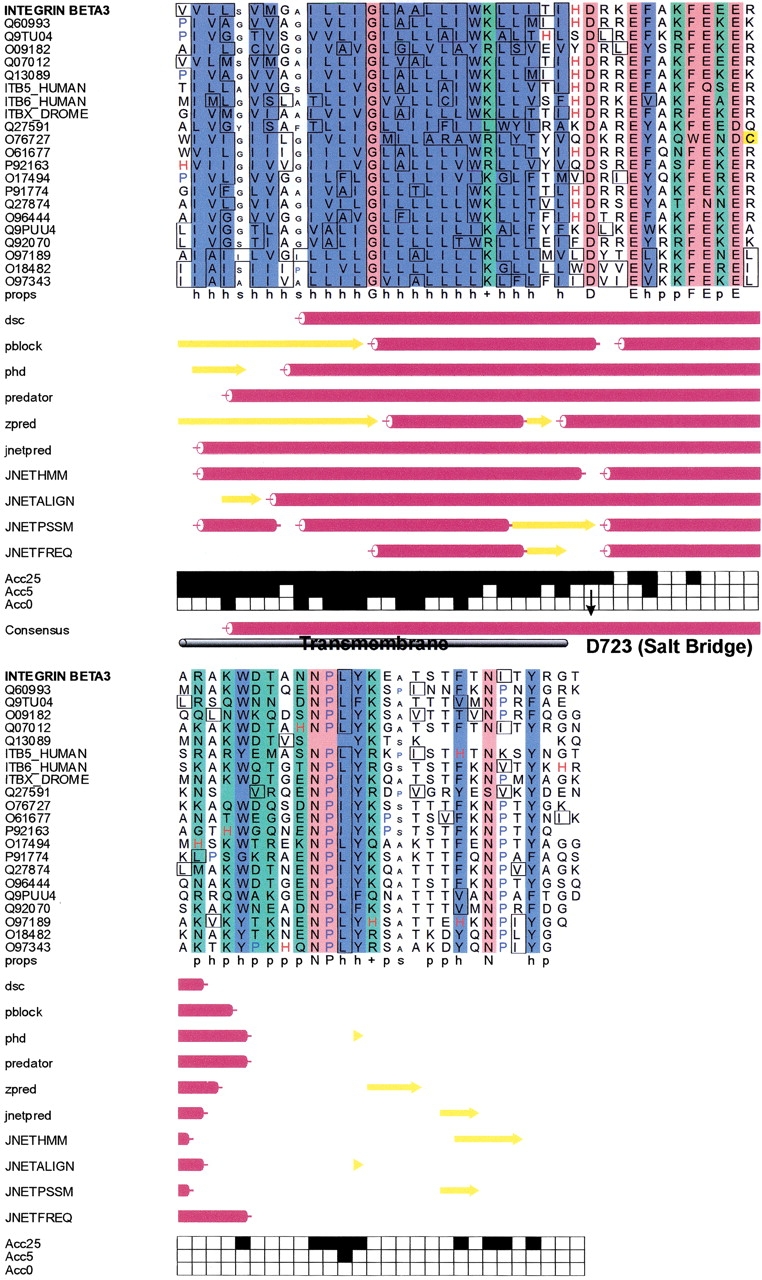

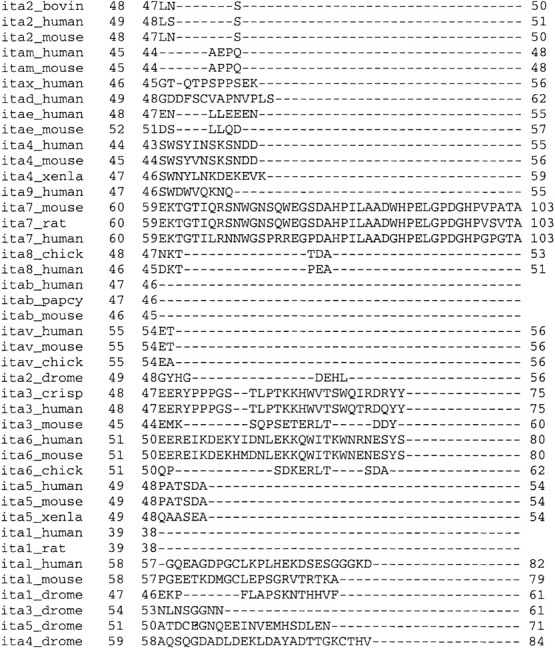

A secondary structure prediction (Fig. 4 ▶), as well as NMR studies (Ulmer et al. 2001), indicates that the membrane proximal region of the cytosolic domain of β3 is also an elongation of the TM helix. Thus the extracellular, as well as intracellular, membrane proximal parts of αIIbβ3 can be assumed to be an approximately linear prolongation of the TM helices.

Fig. 4.

Secondary structure prediction for β3: The secondary structure of parts of the cytosolic domain of integrin β3 was predicted using the web-based prediction server Jpred2. The consensus secondary structure prediction reveals that the TM helix is continued well after the pivotal salt bridge forming residue D723. This in accordance with nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies that also observe a helix propensity for this region.

The low-affinity conformation of αIIbβ3 has to fulfill several requirements based on experimental results: Specific interactions between the cytoplasmic parts of the integrin subunits have to occur (Haas and Plow 1996; Humphries 2000). It has been shown that a salt bridge between D723 of β3 and R995 of αIIb has to be formed (Hughes et al. 1996).

The NMR structure of the myristoylated cytoplasmic domain of αIIb should be sensible in the context of subunit association. That means no clashes but stabilizing contacts between the α- and β-subunits should be established. Also, the crossing angle should be smaller than for the high-affinity conformation, and ligand induced binding sites (LIBS) should be buried in the cytoplasmic tail as well as in the stalk regions (Leisner et al. 1999).

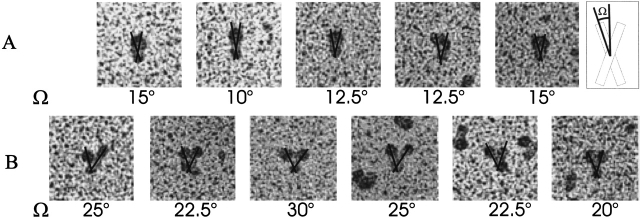

From the electron microscopy studies, we judge that the crossing angle should be smaller than 15° (Fig. 5B ▶). This is the case for cluster 7 (ω = −12.3°) as well as for cluster 11 (ω = −14.6°).

Fig. 5.

Crossing angles of subunits derived from electron microscopy images: The crossing angles of the open and closed conformation were estimated from electron microscopy images. The definition of the crossing angle is shown in the inset. The pictures are taken from Hantgan et al. (1999). (A) Crossing angles of the open conformation after ligand binding. The angle increases significantly. All values are >20°. (B) Crossing angles of the closed conformation before ligand binding. Apparently small crossing angles with values <15° constitute the majority of structures.

Only cluster 11 in Table 2 allows the observed salt bridge to establish itself. For this cluster the other structural requirements of the low-affinity conformation are also met.

When combining the TM model with the NMR structure of the cytosolic part of integrin αIIb and the helical model of β3, stabilizing contacts between the α- and β-subunits can be formed. The crossing angle ensures that LIBS in the extracellular and intracellular domains are buried (Fig. 6A ▶). The combined structure of the TM and intracellular domains served as a starting structure for 50 MD simulations with intramonomer helix restraints and harmonic restraints on the backbone atoms of the TM structure. The five resulting structures with the lowest intermonomer van der Waals energy were averaged. The averaged structure was minimized. A coiled-coil structure of the two helices was formed, establishing contacts between the whole lengths of the two helices. It has been shown by protein engineering that the membrane proximal parts should interact in a coiled-coil fashion (Lu 2001). Additional contacts between the nonhelical tail of αIIb and the helix of β3 are formed (Fig. 6B ▶). The RMSD of the averaged structure to the five single structures is in the order of 1 Å, indicating a well-defined structure.

Fig. 6.

Comparison with experimental results: (A) The interacting surfaces of the helices are shown; blue indicates the surface of β3 and red the surface of αIIb. In the low-affinity conformation a much larger interface is formed. The whole cytosolic domain of αIIb interacts with the helix of β3. The conformation of αIIb in the low-affinity state is in accordance with the NMR structure of the wild-type cytosolic domain of αIIb, whereas the orientation of the nonhelical tail in the high-affinity conformation is taken from the NMR structure of the constitutively active mutant of αIIb. It can be seen that the nonhelical tail enlarges the interface and stabilizes the closed conformation. The high-affinity conformation interacts only in the TM region, exposing intracellular LIBS. (B) It has been shown that the nonhelical tail of αIIb (red surface) interacts with β3 in the low-affinity state. The region of β3 in which this interaction has been stated to occur is shown as blue surface. (C) Fluorescence quenching showed that at least one of the tryptophans is involved in intersubunit interactions. In our model two, the tryptophans interact with each other. (D) A salt bridge is depicted that has been shown to lock the integrin in the closed conformation.

Our model is also in agreement with other experimental data for the dimer in the closed conformation. It was shown by terbium luminescence and electrospray ionization mass results that the sites of contact of the nonhelical tail of the cytosolic domains of αIIb and the helix of β3 are between β3(737) and β3(763) (Fig. 6B ▶). Quenching of tryptophan emission spectra showed that at least one of the tryptophans αIIb(1019), β3(741), or β3(765) interacts with the other subunit (Fig. 6C ▶) (Haas and Plow 1996). The salt bridge can be formed in this conformation (Fig. 6D ▶). A small crossing angle ensures that LIBS are buried in the cytoplasmic domain and that the stalks are close to each other. Thus the small crossing angle, the biochemical studies, and the structural conservation indicate cluster 11 as the conformation representing the low-affinity state.

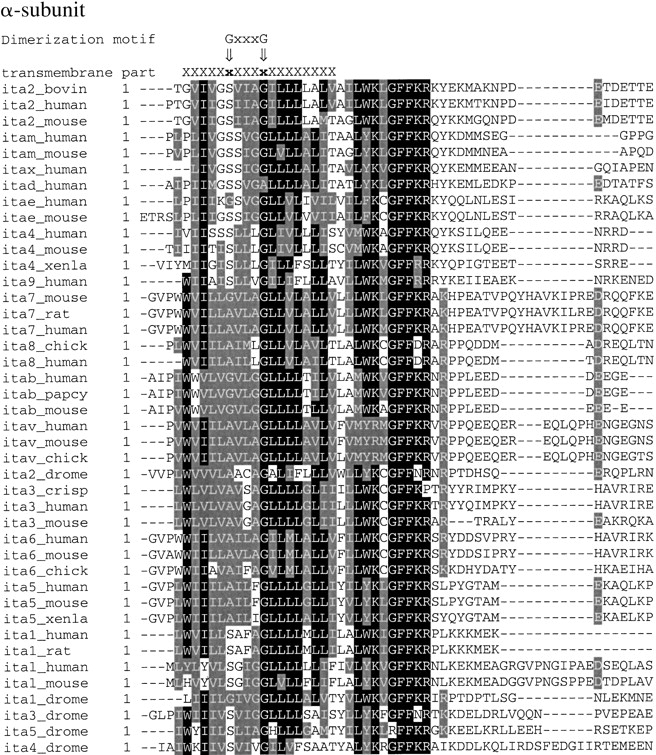

The high-affinity conformation of αIIbβ3 integrin

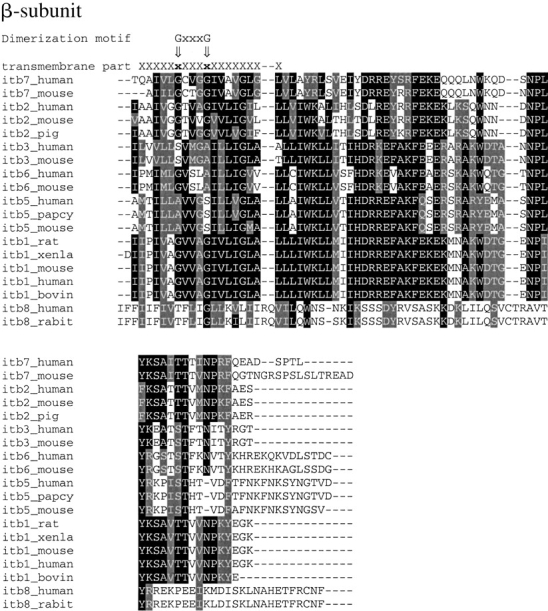

Analyzing electron microscopy images that resolve the extracellular stalk regions lead to the conclusion that the crossing angle between the subunits should be significantly larger than 20° (Fig. 5A ▶). This is the case for cluster 12 (ω = −24.3°) and cluster 5 (ω = −28.5°) but not for cluster 2 (ω = 18.7°). Furthermore, cluster 12 and cluster 5 are rather similar with an RMSD of only 1.7 Å. Thus two of the highly conserved clusters have a similar structure, with cluster 12 being conserved to a higher degree than cluster 5. Considering that the cluster that represents the low-affinity conformation has a crossing angle of −14.6°, the difference in absolute values of 8° to cluster 12 reflects the experimental data better than the difference of 4° in absolute values to cluster 2. In addition, closer investigation of cluster 12 reveals that it bears a high similarity to the structure of Glycophorin A (GpA) with an RMSD of 1.3 Å. The structural similarity to GpA is reflected by a certain sequence similarity. A multiple sequence alignment of the TM and intracellular domains of the α- and β-subtypes of different integrins shows that all the amino acids corresponding to the crucial glycin residues of the central 79Gxxx83G dimerization motif of GpA are small residues such as Gly, Ala, or Ser (Fig. 7 ▶). Although in SDS micelles some of the observed residue combinations of the integrins have been shown to be disruptive (Lemmon et al. 1992), studies in a membrane environment showed a much higher plasticity for these residues (Brosig and Langosch 1998; Russ and Engelman 1999) and established that within the membrane the GxxxG motif appears to be sufficient for dimerization. Although a G79A replacement resulted in significant GpA-dimer even in SDS micelles, G79S was completely disruptive. Nevertheless, in a combinatorial library that tested random sequences for their ability to dimerize in a GpA-like fashion in a membrane environment, Ser is observed quite frequently at positions corresponding to 79G and 83G (Russ and Engelman 1999). It is interesting to note that the residue, which corresponds to 83G of GpA, is nearly completely conserved among all α-integrins. All the studies on GpA have been performed on homodimers. It would be valuable to test how heterodimers would respond to substitutions similar to those observed in integrins. Nevertheless it can be assumed that the TM integrin dimer is less stable than the GpA dimer. This is also reflected by the fact that DPC seems to be dimer disrupting for integrins (Li et al. 2001), whereas GpA forms a stable dimer even in SDS (Lemmon et al. 1992).

Fig. 7.

Sequence alignment of integrin subtypes: The TM and cytosolic domains of different integrins were aligned using ClustalW with default settings. The minimal dimerization motif of GpA, 79Gxxx83G, is indicated as is the TM part that has been included in the global search of helix–helix interactions. With the exception of β8, all residues corresponding to Gly in the minimal dimerization motif are small residues such as Ala, Ser, or Gly. β8 has a Thr at the position relating to 79G. In the α-subunits 83G is highly conserved.

Several lines of evidence indicate cluster 12 as the high-affinity conformation. It is the structurally best conserved cluster among the integrin subtypes. The crossing angle, as well as the difference in crossing angles to the low-affinity state, is in agreement with electron microscopy images, and it bears a structural similarity to GpA that is reflected in a certain sequence similarity.

Transition between open and closed conformation of transmembrane domains

To address the task of elucidating reaction paths between substates of biomolecular systems, MD simulations appear to be ideally suited because the changes of the system with time can be observed directly. One drawback is the huge computational effort involved; especially because transitions are normally connected with energy barriers and thus rather slow, MD simulations are short compared with the timescale of structural transitions. Therefore techniques have been developed to try to determine the correct path even in a short simulation time. With the educt and product conformations known, minimum-biasing MD (Harvey and Gabb 1993), path energy minimization (Smart 1994), the self-penalty path method (Czerminski and Elber 1990), targeted MD (Schlitter et al. 1994), and directed dynamics (El-Kettani and Durup 1992) can in principle describe a reaction pathway. All these methods have in common that either an intuitive pathway is assumed and afterwards refined or that artificial distance restraints are applied to drive the system in the desired direction. In our case the educt and product conformations are both computational models and can only be regarded as low-resolution structures. If the conformations are not correct, no pathway can be found without restraints. On the other hand, applying artificial restraints or guessing an initial pathway with following refinement of this pathway can force the system through a nonphysiological path. But if a path can be detected without additional restraints by plain MD simulations, this further corroborates the validity of the structural models. To avoid additional restraints and simultaneously to accelerate the MD simulations, we performed simulations at elevated temperatures. It has been shown for the related case of protein-folding and protein-unfolding studies that transition states inferred from high temperature simulations are in very good agreement with experiments and simulations performed under physiological conditions (Ladurner et al. 1998; Pande and Rokhsar 1999). Computational considerations forced us to include only the TM regions in vacuo. In the framework of this approximation, reasonable results have been obtained (Adams et al. 1996; Cordes et al. 2001; Sukharev et al. 2001). Our simulations were first performed at 600 K, followed by a simulation at 300 K. We performed MD calculations in vacuo starting with the conformations of the TM domains without the cytosolic domains. We then checked whether or not common intermediates or even the respective other conformation were reached; 150 simulations from each starting structure were performed with different initial velocities, thus obtaining a distribution of possible simulation outcomes.

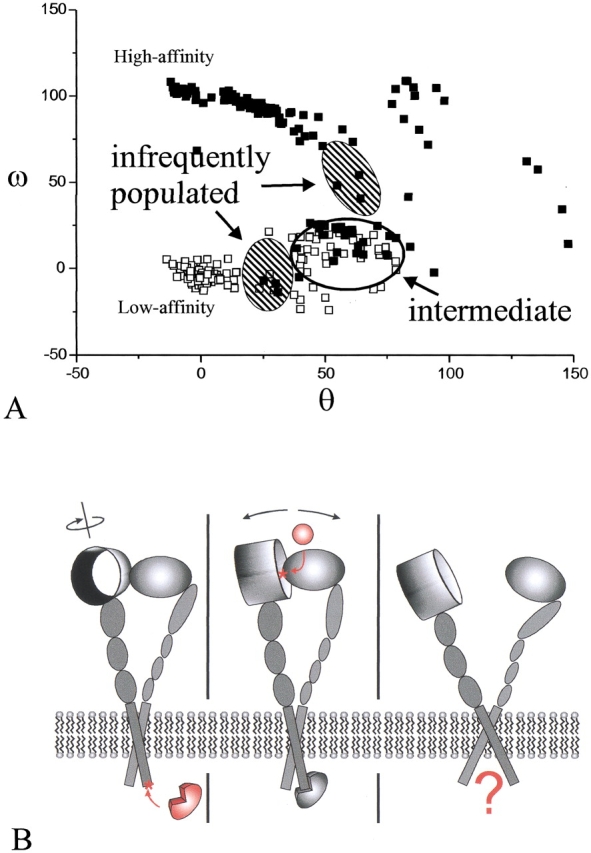

Three-state model

From an examination of the rotation angles with respect to the closed conformation of the resulting structures, it can be seen that although most of the structures remain relatively close to the starting structures, an intermediate conformation is reached from each starting structure. Furthermore there are only two rarely populated conformations (Fig. 8A ▶). This intermediate conformation differs in the rotation of the α-subunit, whereas the β-subunit is virtually unchanged. The crossing angle between the helices is also unchanged. Recent biochemical studies show that the transition from the closed to the open conformation is a multiple, most likely a three-state, process (Boettiger et al. 2001). It also has been shown that truncation of the TM and cytosolic domains of αIIbβ3 renders the integrin constitutively active, whereas without adding ligand the headgroups stay associated (Wippler et al. 1994). Thus we propose that a three-state mechanism exists. The first state is locked by intracellular interaction and has little affinity to ligands, whereas after rotation of the α-subunit without change in the crossing angle, a ligand-binding site is exposed. Ligand binding triggers further conformational changes, which in turn separate the headgroups (Fig. 8B ▶). The intermediate conformation reflects the second state, which we call "activated state."

Fig. 8.

Three-state mechanism of signal transduction: (A) Rotation angles ω and θ (for definition, see Fig. 2 ▶) of the 150 final structures after the simulation. Only part of the ω/θ conformational space is shown. The closed squares represent structures initiating from the GpA-like, high-affinity starting structure, and the open squares represent the structures initiating from the low-affinity conformation. It can be seen that although no structure reaches the respective other conformation, a common intermediate exists. (B) Three-state model of signal transduction in integrins. In accordance with experimental and theoretical studies, intracellular proteins attach to αvβ3 and trigger a rotational movement of the headgroups, exposing the extracellular ligand-binding site (left). Ligands bind at this site (middle) leading to conformational changes in the headgroup region, which in turn evokes separation of the integrin subunits (right). This separation might be a starting point for further intracellular events.

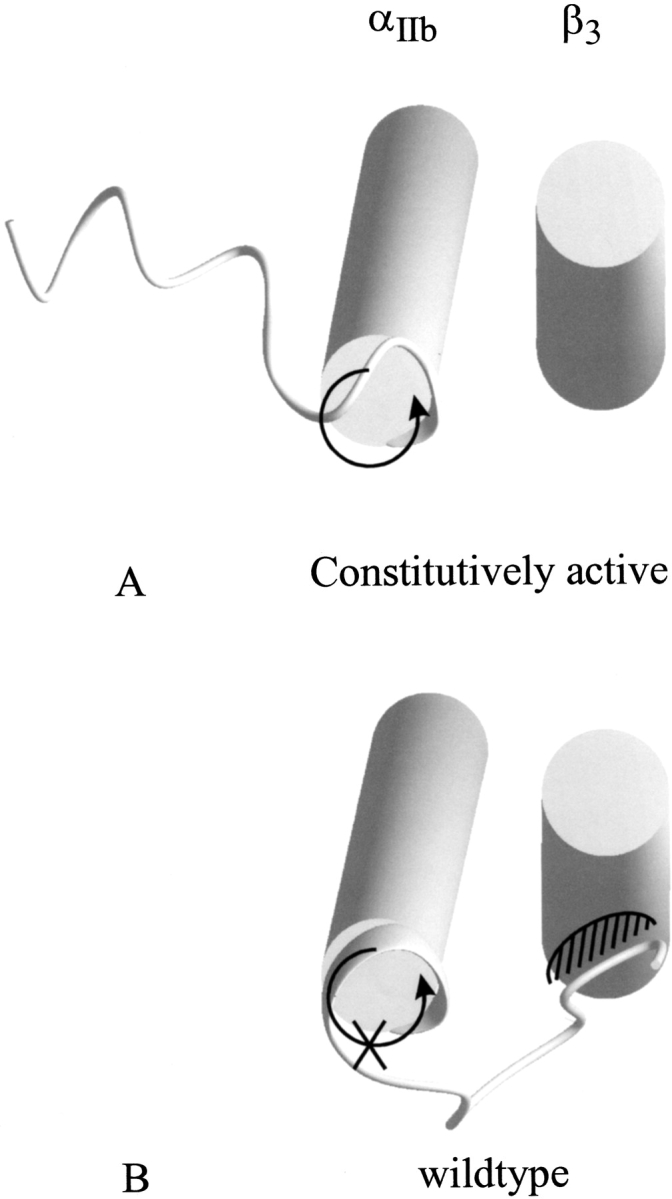

Role of intracellular domain

The intracellular domain plays a key role in switching the protein from an inactive to an activated conformation (Hughes et al. 1996). It has been shown that mutations in the cytosolic domain can switch the protein to constitutively active forms (Hughes et al. 1996). Thus the cytosolic domain, and not the extracellular parts, locks the integrin in the low-affinity state. Here we describe in structural terms how this is performed. The closed state is energetically lowered by the salt bridge between αIIb(R995) and β3(D723). Additional contacts between the cytoplasmic domains occur in the low-affinity conformation. These contacts are lacking in the high-affinity conformation. Furthermore, the cytoplasmic tail of the wild-type αIIb integrin as determined by NMR inhibits the rotational movement necessary to switch from inactive to activated conformation (Fig. 9 ▶). The constitutively active form of the cytoplasmic tail of αIIb, on the other hand, allows such a rotational movement because the orientation of the tail is different. Thus the cytoplasmic domain of αIIb serves two functions: (1) stabilizing the closed form of the dimer by a salt bridge and other interactions between the helices and the cytoplasmic tail of the protein and (2) raising the energy of the transition state. As it turns out, the wild-type cytoplasmic tail does not disfavor the open conformation but rather disfavors the transition state and favors the closed conformation, whereas the constitutively active form does not disfavor the transition state and stabilizes neither the low-affinity nor the high-affinity conformation. For the high-affinity conformation, the distance between the cytosolic tails is too large to allow interactions between these domains. The mode of action of the intracellular ligands, which bind to αIIb and induce signal transduction, appears to be a promotion of a conformational change of the tail of the intracellular domain of αIIb and thus makes the rotational movement of helix A and the transition possible.

Fig. 9.

Inhibition of rotation by intracellular αIIb domain: The view from the cytoplasmic side of the membrane of the constitutively high-affinity (A) and wild-type (B) integrin models. The structure of the α-subunit was solved by NMR. Although in the wild-type form the nonhelical cytoplasmic tail prevents a rotation that is necessary for the transition from low- to high-affinity state, this tail points in the opposite direction in the mutated tail. Thus not only the ground state is destabilized by lacking interactions between the subunits but also the transition is possible because no steric hindrance between the tail of the α-subunit and the helix of the β-subunit occurs. This leads to the hypothesis that intracellular ligands change the orientation of the cytoplasmic tail.

Conclusions

In this work we were able to identify a common structural motif of the TM region of integrins. This structural organization relates to the very stable TM dimer of GpA. For αIIbβ3, we identified the GpA-like structure as the open, high-affinity conformation and determined the closed conformation on the basis of experimental data. A possible transition between these conformations was shown by MD calculations, leading to a three-state model of signal transduction. Our results explain mutational and other biochemical data in structural terms and furthermore allow the design of new experiments to verify our predictions.

Materials and methods

For graphical analysis, the software package InsightII (Biosym/MSI) was used. Figures were made with Origin50 (microcal), MOLMOL (Koradi et al. 1996), or Grasp (Nicholls et al. 1991).

Alignment of integrin sequences

The TM and cytosolic parts of the integrin sequences were obtained from the SwissProt database. They were aligned using ClustalW with default settings of all parameters (Thompson et al. 1994).

Global search

The conformations of pairs of TM helices were searched with rotation angles ω and θ of 0° to 360° for helices A and B, respectively (Fig. 2 ▶), starting with both left- and right-handed crossing angles Ω of 25° and −25°, respectively. Initially the helices were positioned with a vertical shift of zero. ω and θ were incremented in 45° steps, and four trials with different random velocities were performed starting from each conformation using simulated annealing of all atomic coordinates, leaving the vertical shift, in-plane distance, crossing angles, and rotation angles free to vary. The system was simulated 5000 steps with a stepsize of 0.001 psec at 600 K and then simulated 5000 steps with a stepsize of 0.002 psec at 300 K. The resulting 512 structures were grouped into clusters. A cluster was defined as having at least 10 structures with a relative RMSD of the backbone atoms of not more than 1.0 Å from one member of the cluster to at least one other member. The average structure of each cluster was calculated and subject to the same annealing protocol as the starting structures. In the text, the term cluster refers to the average structure of a cluster. This definition of cluster does not apply to the elucidation of the pathway. The search was performed as described by Adams and coworkers (Adams et al. 1995; 1996). The calculations were performed with the software package CNS version 0.5 (Brunger et al. 1998). The united atoms Opls-parameters with explicit polar hydrogens were used (Jorgensen and Tirado-Rives 1988).

Transition

The transition between conformations of the TM part was simulated with intrahelical hydrogen-bonding distance restraints: the distance of Ni and Oi+4 was restrained to a maximum of 2.8 Å. The geometric centers of the helices were restrained to a distance of <10.4 Å. A simulation with 5000 steps with a stepsize of 0.001 psec at 600 K was performed and followed by 5000 steps with a stepsize of 0.002 psec at 300 K. The rotation angles of the final structures were calculated with respect to the initial structures.

Inclusion of cytosolic domains

The secondary structure prediction for integrin β3 was performed by the web-based server Jpred2 (http://jura.ebi.ac.uk:8888/) (Cuff et al. 1998). The NMR structures of integrin αIIb (PDB codes: 1DPK and 1DPQ [constitutively active mutant]) were tethered to the TM part using the program modeler (Sali and Blundell 1993). The full models were subject to 50 simulations with harmonic restraints with a force constant of 10 KJ/mole for the backbone atoms of the TM part. A simulation with 5000 steps with a stepsize of 0.001 psec at 600 K was performed and followed by 5000 steps with a stepsize of 0.002 psec at 300 K. The five structures with the strongest van der Waals interactions between the helices were averaged. The side-chains of the averaged structures were positioned using a mean field approach (Koehl and Delarue 1994). Twenty-five cycles were underdone. The convergence of the mean field was checked by the interaction energy as well as the side-chain entropy. The final structures were minimized with 1000 steps of Powell minimization.

Acknowledgments

K.G. thanks Sarah Stallings for many suggestions and help with the preparation of the manuscript.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.4120102.

References

- Adams, P.D., Arkin, I.T., Engelman, D.M., and Brunger, A.T. 1995. Computational searching and mutagenesis suggest a structure for the pentameric transmembrane domain of phospholamban. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2 154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams, P.D. and Brunger, A.T. 1997. Towards prediction of membrane protein structure. In Membrane protein assembly (ed. G. van Heijne), p. 251. R.G. Landes Company, London.

- Adams, P.D., Engelman, D.M., and Bruenger, A.T. 1996. Improved prediction for the structure of the dimeric transmembrane domain of glycophorin A obtained through global searching. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 26 257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettiger, D., Huber, F., Lynch, L., and Blystone, S. 2001. Activation of alpha(v)beta3-vitronectin binding is a multistage process in which increases in bond strength are dependent on Y747 and Y759 in the cytoplasmic domain of beta3. Mol. Biol. Cell 12 1227–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, J.A., Torres, J., and Arkin, I.T. 2001. A new method to model membrane protein structure based on silent amino acid substitutions. Proteins 44 370–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosig, B. and Langosch, D. 1998. The dimerization motif of the glycophorin A transmembrane segment in membranes: Importance of glycine residues. Protein Sci. 7 1052–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger, A.T., Adams, P.D., Clore, G., Gros, W., Grosse-Kunstleve, R., Jiang, J., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N., Resd, R. et al. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D 54 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes, F.S., Kukol, A., Forrest, L.R., Arkin, I.T., Sansom, M.S., and Fischer, W.B. 2001. The structure of the HIV-1 Vpu ion channel: Modelling and simulation studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1512 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuff, J.A., Clamp, M.E., Siddiqui, A.S., Finlay, M., and Barton, G.J. 1998. JPred: A consensus secondary structure prediction server. Bioinformatics 14 892–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czerminski, R. and Elber, R. 1990. Self-avoiding walk between two fixed points as a tool to calculate reaction paths in large molecular systems. Int. J. Quantum Chem. Quantum Chem. Symp. 24 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- Dedhar, S. and Hannigan, G.E. 1996. Integrin cytoplasmic interactions and bidirectional transmembrane signalling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 8 657–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, X., Gu, M., Weisel, J.W., Nagaswami, C., Bennett, J.S., Bowditch, R., and Ginsberg, M.H. 1993. Long range propagation of conformational changes in integrin αIIbβ3. J. Biol. Chem. 269 23087–23092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durell, S.R., Hao, Y., and Guy, H.R. 1998. Structural models of the transmembrane region of voltage-gated and other K+ channels in open, closed, and inactivated conformations. J. Struct. Biol. 121 263–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Kettani, M.A.E.C. and Durup, J. 1992. Theoretical determination of conformational paths in citrate synthase. Biopolymers 32 561–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley, J., Knight, C.G., Farndale, R.W., Barnes, M.J., and Liddington, R.C. 2000. Structural basis of collagen recognition by integrin alpha2beta1. Cell 101 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frachet, P., Duperray, A., Delachanal, E., and Marguerie, G. 1992. Role of the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains in the assembly and surface exposure of the platelet integrin GPIIb/IIIa. Biochemistry 31 117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, L.J. and Humphries, M.J. 1999. The molecular anatomy of integrins. Adv. Mol. Cell Biol. 28 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, T.A. and Plow, E.F. 1996. The cytoplasmic domain of αIIbβ3. A ternary complex of the integrin alpha and beta subunits and a divalent cation. J. Biol. Chem. 271 6017–6026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantgan, R.R., Paumi, C., Rocco, M., and Weisel, J.W. 1999. Effects of ligand-mimetic peptides Arg-Gly-Asp-X (X = Phe, Trp, Ser) on αIIbβ3 integrin conformation and oligomerization. Biochemistry 38 14461–14474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, S.C. and Gabb, H.A. 1993. Conformational transitions using molecular dynamics with minimum biasing. Biopolymers 33 1167–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemler, M.E. 1998. Integrin associated proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 10 578–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, P.E., Diaz-Gonzalez, F., Leong, L., Wu, C., McDonald, J.A., Shattil, S.J., and Ginsberg, M.H. 1996. Breaking the integrin hinge. A defined structural constraint regulates integrin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 271 6571–6574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries, M.J. 2000. Integrin structure. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 28 311–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, P.M. and Vogel, H.J. 2000. Structures of the platelet calcium- and integrin-binding protein and the alphaIIb-integrin cytoplasmic domain suggest a mechanism for calcium-regulated recognition; homology modelling and NMR studies. J. Mol. Recognit. 13 83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, W. and Tirado-Rives, J. 1988. The OPLS potential function for proteins, energy minimization for crystals of cyclic peptides and crambin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 110 1657–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehl, P. and Delarue, M. 1994. Application of a self-consistent mean field theory to predict protein side-chains conformation and estimate their conformational entropy. J. Mol. Biol. 239 249–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koradi, R., Billeter, M., and Wuthrich, K. 1996. MOLMOL: A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladurner, A.G., Itzhaki, L.S., Daggett, V., and Fersht, A.R. 1998. Synergy between simulation and experiment in describing the energy landscape of protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95 8473–8478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leisner, T.M., Wencel-Drake, J.D., Wang, W., and Lam, S.C.-T. 1999. Bidirectional transmembrane modulation of integrin αIIbβ3 conformations. J. Biol. Chem. 274 12945–12949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon, M.A., Flanagan, J.M., Treutlein, H.R., Zhang, J., and Engelman, D.M. 1992. Sequence specificity in the dimerization of transmembrane alpha-helices. Biochemistry 31 12719–12725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Toledano, S. 1999. Platelet signal transduction pathways. Could we organize them into a "hierarchy"? Haemostasis 29 4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, R., Babu, C.R., Lear, J.D., Wand, A.J., Bennett, J.S., and DeGrado, W.F. 2001. Oligomerization of the integrin alpha IIbbeta 3: Roles of the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98 12462–12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddington, R.C. and Bankston, L.A. 2000. The structural basis of dynamic cell adhesion: Heads, tails, and allostery. Exp. Cell Res. 261 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S., Calderwood, D.A., and Ginsberg, M.H. 2000. Integrin cytoplasmic domain-binding proteins. J. Cell Sci. 113 3563–3571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C., Takagi, J., and Springer, T.A. 2001. Association of the membrane proximal regions of the alpha and beta subunit cytoplasmic domains constrains an integrin in the inactive state. J. Biol. Chem. 276 14642–14648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, A., Sharp, K.A., and Honig, B. 1991. Protein folding and association: Insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 11 281–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottemann, K.M., Xiao, W., Shin, Y.-K., and Koshland, D.E., Jr. 1999. A piston model for transmembrane signaling of the aspartate receptor. Science 285 1751–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pande, V.S. and Rokhsar, D.S. 1999. Molecular dynamics simulations of unfolding and refolding of a β-hairpin fragment of protein G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96 9062–9067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J.A., Visentin, G.P., Newman, P.J., and Aster, R.H. 1998. A recombinant soluble form of the integrin αIIbβ3 (GPIIb-IIIa) assumes an active, ligand-binding conformation and is recognized by GPIIb-IIIa-specific monoclonal, allo-, auto-, and drug-dependent platelet antibodies. Blood 92 2053–2063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plow, E.F., Haas, T.A., Zhang, L., Loftus, J., and Smith, J.W. 2000. Ligand binding to integrins. J. Biol. Chem. 275 21785–21788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ, W.P. and Engelman, D.M. 1999. TOXCAT: A measure of transmembrane helix association in a biological membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96 863–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali, A. and Blundell, T.L. 1993. Comparative protein modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234 779–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom, M.S. and Davison, L. 2000. Modeling transmembrane helix bundles by restrained MD simulations. Methods Mol. Biol. 143 325–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom, M.S., Kerr, I.D., Law, R., Davison, L., and Tieleman, D.P. 1998. Modelling the packing of transmembrane helices: Application to aquaporin-1. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 26 509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlitter, J., Engels, M., and Krueger, P. 1994. Targeted molecular dynamics: A new approach for searching pathways of conformational transitions. J. Mol. Graph. 12 84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.P., III, Scott, J.P., II, Chao, Y.-L., and Newman, P.J. 1998. A frameshift mutation at Gly975 in the transmembrane domain of GPIIb prevents GPIIb-IIIa expression. Analysis of two novel mutations in a kindred with type I Glanzmann thrombasthenia. Thromb. Haemost. 80 546–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart, O.S. 1994. A new method to calculate reaction paths for conformational transitions of large molecules. Chem. Phys. Lett. 222 405–512. [Google Scholar]

- Sukharev, S., Durell, S.R., and Guy, H.R. 2001. Structural models of the mscl gating mechanism. Biophys. J. 81 917–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, J., Erickson, H.P., and Springer, T.A. 2001. C-terminal opening mimics 'inside-out' activation of integrin alpha5beta1. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 412–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.D., Higgins, D.G., and Gibson, T.J. 1994. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmer, T.S., Yaspan, B., Ginsberg, M.H., and Campbell, I.D. 2001. NMR analysis of structure and dynamics of the cytosolic tails of integrin αIIbβ3 in aqueous solution. Biochemistry 40 7498–7508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallar, L., Melchior, C., Plancon, S., Drobecq, H., Lippens, G., Regnault, V., and Kieffer, N. 1999. Divalent cations differentially regulate integrin alphaIIb cytoplasmic tail binding to beta3 and to calcium- and integrin-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 274 17257–17266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova, O., Haas, T., Plow, E.F., and Qin, J. 2000. A structural basis for integrin activation by the cytoplasmic tail of the αIIb-subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97 1450–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wippler, J., Kouns, W.C., Schlaeger, E.J., Kuhn, H., Hadvary, P., and Steiner, B. 1994. The integrin alpha IIb-beta 3, platelet glycoprotein IIb-IIIa, can form a functionally active heterodimer complex without the cysteine-rich repeats of the beta 3 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 269 8754–8761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, J.P., Stehle, T., Diefenbach, B., Zhang, R., Dunker, R., Scott, D.L., Joachimiak, A., Goodman, S.L., and Arnaout, M.A. 2001. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin αVβ3. Science 294 339–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]