Abstract

One of the mechanisms by which mutations in superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (fALS) is proposed to involve the accumulation of detergent-insoluble, disulfide-cross-linked, mutant protein. Recent studies have implicated cysteine residues at positions 6 and 111 as critical in mediating disulfide cross-linking and promoting aggregation. In the present study, we used a panel of experimental and disease-linked mutations at cysteine residues of SOD1 (positions 6, 57, 111, and 146) in cell culture assays for aggregation to demonstrate that extensive disulfide cross-linking is not required for the formation of mutant SOD1 aggregates. Experimental mutants possessing only a single cysteine residue or lacking cysteine entirely were found to retain high potential to aggregate. Furthermore we demonstrate that aggregate structures in symptomatic SOD1-G93A mice can be dissociated such that they no longer sediment upon ultracentrifugation (i.e. appear soluble) under relatively mild conditions that leave disulfide bonds intact. Similar to other recent work, we found that cysteines 6 and 111, particularly the latter, play interesting roles in modulating the aggregation of human SOD1. However, we did not find that extensive disulfide cross-linking via these residues, or any other cysteine, is critical to aggregate structure. Instead we suggest that these residues participate in other features of the protein that, in some manner, modulate aggregation.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS),2 a progressive neuro-degenerative disease characterized by the loss of upper and lower motor neurons, typically presents with unknown etiology (sporadic ALS). Rarely cases of ALS exhibit dominant patterns of inheritance (familial ALS), and a subset of these cases are caused by mutations in SOD1 (1). More than 100 mutations in SOD1 have been identified in cases of fALS. The majority of these fALS-linked SOD1 mutations are point mutations. A subset of fALS mutations causes shifts in the reading frame or introduces early termination codons, resulting in the production of C-terminally truncated proteins.

SOD1 is a metalloenzyme responsible for metabolizing oxygen radicals that are produced during normal cellular metabolism. The active enzyme is a homodimer of two 153-amino acid subunits with each subunit containing eight β-strands, an active site that binds copper, a binding site for zinc, an electrostatic loop that directs the substrate into the active site, and an intramolecular disulfide bond between cysteine 57 and cysteine 146 (2). Together these structural aspects of SOD1 produce an extremely stable protein, retaining its structure in 1% SDS and 8 m urea (3). SOD1 is primarily located in the cytosol but has been found at lower levels in nuclei, peroxisomes, and mitochondria (4–6).

The effects of fALS mutations on the normal enzyme activity, turnover, and folding of SOD1 vary considerably (7–9). In cell culture and in vitro models, enzyme activity ranges from undetectable to near normal (7, 10–13); most mutations accelerate the rate of protein turnover (7, 12); and many mutations increase the susceptibility of SOD1 to disulfide reduction (14). Because some SOD1 mutants retain high activity (12) and because the targeted deletion of SOD1 in mice does not induce ALS-like symptoms (15), mutant SOD1 is proposed to cause disease by the acquisition of toxic properties.

One proposed toxic property is aggregation of SOD1 protein. Our group and others have found that eight fALS mutants (in transgenic mouse models) and 13 fALS mutants (in cell culture models) exhibit a heightened potential to form aggregates (16–23). These detergent-insoluble (aggregated) forms of SOD1 proteins contain molecules that are cross-linked by intermolecular disulfide bonds (24–26). Within each SOD1 subunit, there are four cysteine residues at amino acids 6, 57, 111, and 146; an intramolecular disulfide bond between cysteine residues at 57 and 146 is found in the natively folded holoenzyme (2). In symptomatic SOD1 transgenic mice, high molecular weight forms of SOD1 are visible by SDS-PAGE when detergent-insoluble protein is electrophoresed in the absence of reducing agents (24, 26). These high molecular weight, disulfide-linked forms of SOD1 become more abundant as ALS-like symptoms progress (24–26).

There has been considerable attention focused recently on the role of disulfide cross-linking in the aggregation of SOD1 (both fALS mutant and wild-type protein) (24–29). Initial studies of purified SOD1 in vitro suggested that all four cysteine residues of SOD1 were capable of forming intermolecular disulfide bonds with cysteines at 57 and 146 perhaps playing a more important role (24). However, in the past year, there have been several studies that used cell culture models or in vitro aggregation studies to examine the role of individual cysteine residues in mutant SOD1 aggregation (27–29). Collectively these studies have focused attention on cysteines 6 and 111 of SOD1 as playing important roles in modulating mutant SOD1 aggregation with the putative mechanism involving formation of aberrant intermolecular disulfide bonds.

In the present study, we systematically examined the role of the four cysteine residues in SOD1 in the formation of aberrant disulfide bonds and protein aggregates. Our data suggest that although cysteines 6 and 111 may play critical roles in the formation of SOD1 aggregates the mechanism of mutant protein aggregation does not appear to require extensive intermolecular disulfide linkages. Analysis of a series of experimental mutants led us to conclude that cysteines 6 and 111 may modulate structural features of the protein, apart from disulfide linkages, that influence aggregate formation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Tissue Culture Transfection and Transgenic Mice—fALS and experimental mutations were created in the cDNA of human SOD1 or mouse SOD1 using standard PCR strategies with oligonucleotides that introduce the specific point mutations. All mutant cDNAs created in this manner were sequenced in their entirety to verify the presence of the desired mutations and the absence of undesired mutations. SOD1 mutants were expressed in the pEF-BOS vector (30). HEK293FT cells were cultured in 60-mm poly-d-lysine-coated dishes. Upon reaching 95% confluency, cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and then harvested after 24 h.

The SOD1 transgenic mice have been characterized previously: the G93A variant (B6SJL-TgN(SOD1-G93A)1Gur; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) (31), the G86R variant (FVB-Tg(Sod1-G86R)M1Jwg/J; The Jackson Laboratory) (32), and the wild-type protein (line 76) (33).

SOD1 Aggregation Assay by Differential Extraction—The procedures used to assess SOD1 aggregation by differential detergent extraction and centrifugation were similar to previous descriptions (20). Spinal cords were homogenized with a probe sonicator (Microson XL2000, 2 watts at 22.5 kHz; Misonix, Farmingdale, NY) in 1:10 (w/v) 1× TEN (10 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, and 100 mm NaCl). In cell culture experiments, cells were scraped from the culture dish in phosphate-buffered saline and centrifuged to pellet the cells before the pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of 1× TEN. Spinal cord homogenates and resuspended cell culture pellets were then mixed with an equal volume of 2× extraction buffer 1 (10 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, 100 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P40, and 1× protease inhibitor mixture) and sonicated as above. The resulting lysate was centrifuged for 5 min at >100,000 × g in a Beckman Airfuge to separate a non-ionic detergent-insoluble pellet (P1) from the supernatant (S1). The supernatant (S1) was decanted and saved for analysis. The pellet (P1) was resuspended in 200 μl of 1× extraction buffer 2 (10 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, 100 mm NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P40, and 1× protease inhibitor mixture) and sonicated to resuspend. The extract was then centrifuged for 5 min at >100,000 × g in a Beckman Airfuge to separate a pellet (P2) from the supernatant. The P2 fraction was resuspended in buffer 3 (10 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, 100 mm NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P40, 0.25% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, and 1× protease inhibitor mixture) by sonication and saved for analysis.

In variations of this procedure, buffer 1 was modified to include 100 mm iodoacetamide as noted in figure legends and the text. Additionally in one set of experiments (see Fig. 8) SDS was substituted for Nonidet P-40 in all extraction buffers. 2× SDS buffer (10 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, 100 mm NaCl, 1% SDS, and 1× protease inhibitor mixture) was substituted for buffer 1, and a 1× SDS buffer (10 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, 100 mm NaCl, 0.5% SDS, and 1× protease inhibitor mixture) was substituted for buffers 2 and 3. Protein concentration was measured in S1 and P2 fractions by the BCA method as described by the manufacturer (Pierce).

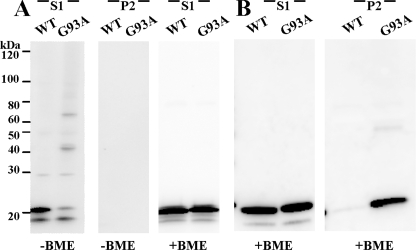

FIGURE 8.

Disulfide bonds are not sufficient to maintain SOD1 aggregate structure. A, spinal cord tissue from asymptomatic WT and symptomatic G93A SOD1 transgenic mice was extracted in 0.5% SDS detergent and iodoacetamide. B, standard extraction in Nonidet P-40 and centrifugation of the same tissues utilized in A. Samples were run in the presence or absence of reducing agent (β-mercaptoethanol (BME)), as noted, in 4–20% Tris-glycine gels. Immunoblots were probed with m/hSOD1 antiserum. S1, detergent-soluble (5 μg). P2, detergent-insoluble (20 μg).

Immunoblotting—Standard SDS-PAGE was performed in 18 or 4–20% Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen). Samples were boiled for 5 min in Laemmli sample buffer prior to electrophoresis (34). In some experiments, reducing agent (5% β-mercaptoethanol) was omitted from the sample buffer. Immunoblots were probed with rabbit polyclonal antibodies termed hSOD1 or m/hSOD1 at dilutions of 1:2500. The hSOD1 antibody is a peptide antiserum that binds to amino acids 24–36 (not conserved between mouse and human SOD1 proteins), and m/hSOD1 antibody is a peptide antiserum that recognizes amino acids 124–136 (conserved between mouse and human SOD1 proteins) (7).

Quantitative Analysis of Immunoblots—Quantification of the SOD1 protein in insoluble and soluble fractions was performed by measuring the band intensity of SOD1 in each lane using a Fuji imaging system (FUJIFILM Life Science, Stamford, CT). The untransfected control served as background. SOD1 aggregation propensity was a function of the ratio of the band intensity in the insoluble fraction to that of the soluble fraction. The mean and S.E. were calculated for the aggregation propensity of each sample in each experiment. A homoscedastic Student's t test was used to calculate significance. A summary of statistical data is provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Relative aggregation of natural fALS and experimental SOD1 mutants

The relative aggregation potential is based on the mean ratio of insoluble to soluble protein for each SOD1 mutant. –, ratio not statistically different from WT; +, ratio of insoluble to soluble statistically different from WT. The nomenclature for the last five mutants in the table is identical to that used in Figs. 2 and 3 (see legends).

| SOD1 construct | Production of aggregates in 24 h | p value (compared with WT) | Mean ratio insoluble to soluble |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | - | 0.10 | |

| G85R | + | <0.0001 | 0.99 |

| C6G | + | 0.0002 | 0.92 |

| C6F | + | 0.0005 | 1.08 |

| C111Y | + | 0.0005 | 0.51 |

| C111S | - | 0.71 | 0.07 |

| C146R | + | <0.0001 | 1.3 |

| C6G/C111S | - | 0.74 | 0.07 |

| C6G/C111Y | - | 0.58 | 0.06 |

| C6F/C111S | + | 0.06 | 0.45 |

| G85R/C111S | - | 0.90 | 0.12 |

| CSYR | + | 0.0001 | 0.84 |

| GCYR | - | 0.62 | 0.04 |

| GSCR | + | <0.0001 | 0.98 |

| GSYC | - | 0.48 | 0.01 |

| GSYR | - | 0.63 | 0.06 |

| FSYR | + | 0.0009 | 0.89 |

RESULTS

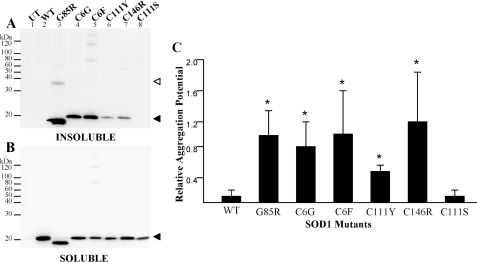

Our initial study focused on examining known fALS mutations at cysteine residues to determine whether loss of any single cysteine residue diminishes SOD1 aggregation. This initial study also provided a reference point with which to compare our next set of studies when these mutations were experimentally combined in recombinant SOD1 proteins. FALS-linked SOD1 cysteine mutants (C6G, C6F, C111Y, and C146R) were expressed in HEK293FT cells, and the cell lysates were separated into detergent-soluble and -insoluble fractions following previously established protocols (20). All four mutants produced detergent-insoluble, sedimentable forms of mutant protein. In this assay, the soluble fractions (Fig. 1B) are representative of the steady-state levels of each mutant (an indication of the efficiency of transfection and level of expression). These experiments and those that follow included the G85R mutant as a positive control; this mutant exhibits anomalous migration in SDS-PAGE, migrating slightly faster than expected for its molecular weight. The aggregation potential, a measure comparing the band intensity of the detergent-insoluble fraction (Fig. 1A) with the detergent-soluble fraction (Fig. 1B), for each of the cysteine mutants was significantly different from wild-type protein (Fig. 1C).

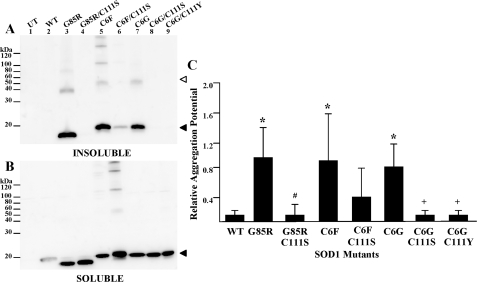

FIGURE 1.

SOD1 aggregation of fALS cysteine mutants in transfected cells. Mutants were expressed in HEK293FT cells, and aggregate levels were determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” UT, untransfected cells provide a negative control. WT, cells transfected with vectors for WT SOD1, which does not aggregate. SOD1-G85R (G85R), a robustly aggregating fALS mutant, provides a positive control. SDS-PAGE was performed in the presence of a reducing agent in an 18% Tris-glycine gel. Immunoblots were probed with an antiserum specific for human SOD1 (hSOD1). A, P2, detergent-insoluble protein fraction (20 μg). B, S1, detergent-soluble protein fraction (5 μg). C, relative aggregation is a function of the amount of SOD1 found in the pellet fraction as compared with the supernatant (see “Experimental Procedures”). The graph represents the mean (±S.E. (error bars)) of at least three different experiments (see Table 1 for a summary of statistical data). All fALS mutants were statistically different from wild-type SOD1: *, p < 0.001. C111S was not statistically different from wild-type SOD1. Open arrowhead, dimer-sized SOD1 molecules. Closed arrowhead, monomeric SOD1 molecules.

The insoluble fractions from cells transfected with SOD1-G85R often contained a form of the protein that migrates at a size expected for a dimer. Interestingly lysates from cells that expressed the C6F mutant (alone or in combination with other mutations; see below) invariably contained forms of mutant SOD1 that migrated at higher molecular weight; often a laddering effect was noted that is indicative of assembly of some type of repeating structure. These structures persisted despite boiling in the presence of SDS and β-mercaptoethanol; thus, they are presumably either molecules that are covalently cross-linked by mechanisms other than disulfide or are assemblies of mutant SOD1 that are resistant to denaturation. In the case of C6F, these multimer-like structures were also detected in detergent-soluble fractions. The origin and relative importance of these structures is presently unclear.

In analyzing the data from the cysteine mutants, we noted variability in the amount of aggregated mutant protein produced from one experiment to the next possibly due to variation in transfection efficiency between experiments. For example, the immunoblot shown in Fig. 1A suggests that the C146R mutant produces less insoluble protein than the C6G or C6F mutants. However, when measurements of multiple immunoblots from replicate experiments were compared, the C146R mutant was not reproducibly different from the other cysteine mutants (Fig. 1C and Table 1). The mutation of cysteine 111 to serine, a non-fALS mutation, did not produce an SOD1 protein that spontaneously aggregates (Fig. 1, A (lane 8) and C, and Table 1). In the analysis of these mutants and in the studies that follow, the principal outcome measure was whether the amount of mutant protein in the detergent-insoluble fraction at ∼24 h post-transfection was statistically different from wild-type SOD1, an indication of aggregation. More subtle differences in aggregation levels between mutants (e.g. C6F versus C111Y, aggregation potentials of 1.08 and 0.51, respectively; see Table 1) are difficult to interpret and were not the focus of this study. The only measure of interest was that both mutants score as statistically different from wild-type protein. Overall we can conclude that fALS mutations at cysteine residues 6, 111, or 146 induce, possibly to varying degrees, aggregation of the protein.

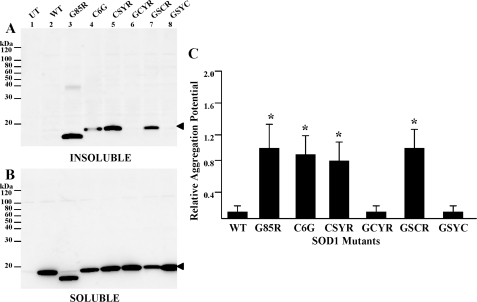

To assess the roles of individual cysteine residues in mutant SOD1 aggregation, four SOD1 constructs were created, each of which contained one intact cysteine residue with the other three cysteines mutated (C6G, C57S, C111Y, or C146R). In this experiment, the C57S mutation is an experimental mutation. When we began this work, no fALS mutations at cysteine 57 were known, and the C57S mutation serves only as a means to eliminate the cysteine residue. These mutants were expressed in HEK293FT cells, and cell lysates were assayed for aggregate formation as described above. When cysteine 6 (C57S/C111Y/C146R; labeled CSYR) or cysteine 111 (C6G/C57S/C146R; labeled GSCR) were intact, detergent-insoluble mutant protein was consistently detected within 24 h (Fig. 2A, lanes 5 and 7, and Table 1). In all mutants, a considerable fraction of the mutant protein was soluble in detergent (Fig. 2B), an indicator of the overall level of expression of the different mutants. From replicate experiments, the aggregation potentials for mutants with cysteine 6 or cysteine 111 intact were determined to be significantly different from wild-type SOD1 protein (Fig. 2C and Table 1). Much less aggregated SOD1 was detected when cysteine 57 (C6G/C111Y/C146R; labeled GCYR) or cysteine 146 (C6G/C57S/C111Y; labeled GSYC) were the only cysteines intact (Fig. 2A, lanes 6 and 8). Neither of these latter two mutants differed from the aggregation potential for wild-type SOD1 (Fig. 2C and Table 1). Notably the two mutants that failed to form aggregates (C6G/C111Y/C146R and C6G/C57S/C111Y) produced soluble forms of these proteins at levels equivalent to those that produced aggregates (Fig. 2B, lanes 6 and 8), indicating that similar levels of expression were achieved. These results indicate that cysteine 6 and cysteine 111 play important roles in inducing the aggregation of human SOD1.

FIGURE 2.

Role of cysteines 6 and 111 in SOD1 aggregation. Mutants were expressed in HEK293FT cells, and aggregate levels were determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” SDS-PAGE was performed in the presence of a reducing agent in an 18% Tris-glycine gel. Immunoblots were probed with m/hSOD1 antiserum. A, P2, detergent-insoluble protein fraction (20 μg). B, S1, detergent-soluble protein fraction (5 μg). C, quantification of the ratio of SOD1 in pellet fractions relative to supernatant was assessed as a measure of relative aggregation. The data represents the mean (±S.E. (error bars)) of at least three different experiments. Mutants where the ratios were statistically different from wild-type SOD1 are marked by * (p < 0.0001). Two mutants were not statistically different from wild-type SOD1: C6G/C111Y/C146R (GCYR) and C6G/C57S/C111Y (GSYC). Closed arrowhead, monomeric SOD1 molecules. UT, untransfected cells; CSYR, C57S/C111Y/C146R; GSCR, C6G/C57S/C146R.

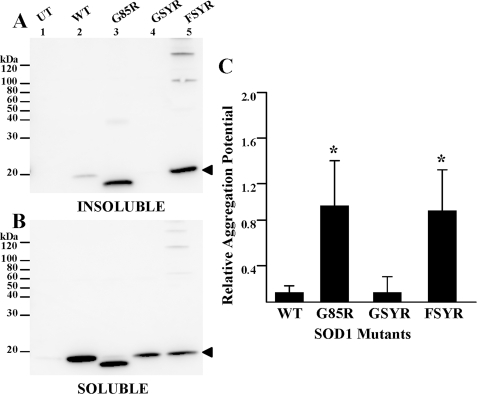

Because our studies indicate that proteins containing only a single cysteine at 6 or 111 alone will rapidly aggregate, we sought to determine whether these residues are required for SOD1 aggregation. Two constructs were generated in which all four cysteine residues (C6G or F, C57S, C111Y, and C146R) were mutated and expressed in HEK293FT cells for assessment of aggregation. One of these constructs in which cysteine 6 was mutated to glycine in the context of three other mutants (C6G/C57S/C111Y/C146R) failed to produce aggregates within 24 h (Fig. 3A, lane 4). However, when cysteine 6 was mutated to phenylalanine (C6F/C57S/C111Y/C146R), the insoluble fraction contained significant amounts of aggregated protein (Fig. 3A, lane 5). The aggregation potential for the C6F version of the four-cysteine variant (C6F/C57S/C111Y/C146R) was significantly different from WT SOD1 and roughly equivalent to the natural fALS mutant SOD1-G85R (Fig. 3C and Table 1). The difference in the propensity of the two four-Cys mutants to aggregate did not appear to be due to a lower expression of C6G version as the level of this mutant protein in the soluble fraction was similar to that of the C6F version (Fig. 3B, lanes 4 and 5). Thus, although cysteines 6 and 111 may play a role in modulating the rate or propensity of mutant human SOD1 to aggregate, the presence of a cysteine residue is not required for rapid aggregate formation.

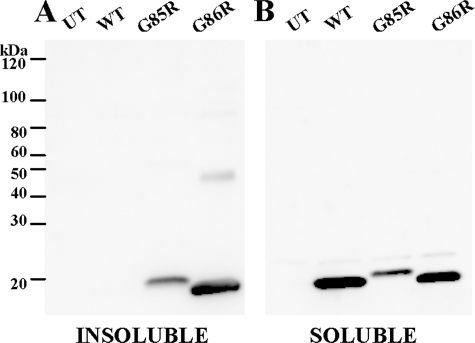

FIGURE 3.

Cysteine residues are not required for SOD1 aggregate formation. Mutants were expressed in HEK293FT cells, and aggregate levels were determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” SDS-PAGE was performed in the presence of a reducing agent in an 18% Tris-glycine gel. Immunoblots were probed with m/hSOD1 antiserum. A, P2, detergent-insoluble protein fraction (20 μg). B, S1, detergent-soluble protein fraction (5 μg). C, quantification of relative aggregation potential (mean ratio ± S.E. (error bars)). Mutants G85R and C6G/C57S/C111Y/C146R (FSYR) were significantly different from the aggregation potential of WT SOD1: *, p < 0.0009. Open arrowhead, monomeric SOD1 molecules. UT, untransfected cells; GSYR, C6G/C57S/C111Y/C146R.

To further explore the role of cysteine residues 6 and 111 in aggregation, we produced a series of constructs in which these two cysteine residues were manipulated. Using the cell aggregation assay described above, we observed that when the C111S mutation was added to C6G, C6F, or G85R, less detergent-insoluble protein was formed as compared with the fALS mutants alone (Fig. 4A, lanes 4, 6, 8, and 9). The level of aggregated protein in cells transfected with C6G/C111S and G85R/C111S double mutants was not different from that of cells transfected with WT SOD1 (Fig. 4C and Table 1). Next the fALS mutation at cysteine 111 (C111Y) was combined with the fALS mutant at cysteine 6 (C6G). Although each of these fALS mutants aggregated when mutated alone (see Fig. 1A), when combined the amount of detergent-insoluble SOD1 detected was not different from WT SOD1 (Fig. 4, A and C, and Table 1). All combination mutants were detected in the soluble fraction at similar levels, indicating that the protein was stably expressed and that only a fraction of the total mutant SOD1 protein aggregates (Fig. 4B). These data provide evidence that cysteines 6 and 111 play a role in the formation of SOD1 aggregates with the rate of aggregation slowing significantly when cysteine 111 was mutated to serine.

FIGURE 4.

Role of cysteine 111 in mutant SOD1 aggregation. Mutants were expressed in HEK293FT cells, and aggregate levels were determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” SDS-PAGE was performed in the presence of a reducing agent in an 18% Tris-glycine gel. Immunoblots were probed with m/hSOD1 antiserum. A, P2, detergent-insoluble protein fraction (20 μg). B, S1, detergent-soluble protein fraction (5 μg). C, relative aggregation ratios (mean ratio ± S.E. (error bars)) of at least three different experiments are graphed. All fALS mutants were statistically different from wild-type SOD1: *, p < 0.0005. The ratios of insoluble to soluble SOD1 for all fALS mutants that were combined with mutated cysteine 111 were not statistically different from wild-type SOD1: G85R/C111S, C6F/C111S, C6G/C111S, and C6G/C111Y. +, C6G was significantly different from C6G/C111S and from C6G/C111Y (p < 0.009). C6F did not differ from C6F/C111S. #, G85R was statistically different from G85R/C111S (p < 0.004). Open arrowhead, dimer-sized SOD1 molecules. Closed arrowhead, monomeric SOD1 molecules. UT, untransfected cells.

Although the foregoing studies implicate a role for cysteines 6 and 111 in promoting aggregation with mutation of cysteine 111 to serine appearing to strongly suppress aggregation (also see Refs. 28 and 29), it is noteworthy that mouse SOD1 naturally encodes serine at position 111 and possesses only three cysteine residues in total (equivalent to positions 6, 57, and 146 in human protein). If the mutation of cysteine 111 to serine reduces aggregation, then the prediction would be that mouse SOD1 encoding fALS mutations should not be prone to aggregate. Previous studies have established a transgenic mouse model of fALS by the expression of mouse SOD1 encoding the equivalent to the human G85R mutation (32). These mice exhibit a rapidly progressing paralytic disorder. To determine the importance of cysteine 111 in vivo, spinal cord tissue from symptomatic SOD1-G86R mice was assayed for SOD1 aggregation and found to accumulate detergent-insoluble SOD1 (Fig. 5A). Compared with mice expressing high levels of WT human SOD1, the symptomatic G86R mice contained high levels of insoluble mouse SOD1. In the spinal cords of the WT human SOD1 mice, the vast majority of the SOD1 was soluble in detergent, whereas in the G86R spinal cord tissue it appeared as though the majority of accumulated SOD1 was insoluble in detergents (Fig. 5, compare A and B). This finding demonstrates that encoding a serine at 111 does not block the aggregation of mouse SOD1.

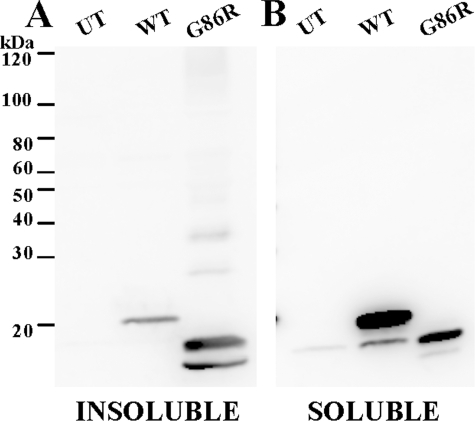

FIGURE 5.

Symptomatic G86R mice form detergent-insoluble species in spinal cord tissue. Spinal cords from WT and G86R mice were extracted in buffers containing Nonidet P-40 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” SDS-PAGE was performed in the presence of a reducing agent in an 18% Tris-glycine gel. Immunoblots were probed with m/hSOD1 antiserum. Experiments were replicated twice; a representative example is shown. A, P2, detergent-insoluble protein fraction (20 μg). B, S1, detergent-soluble protein fraction (5 μg). UT, untransfected cells.

Because our assessment of the experimental mutation of human SOD1 (G85R/C111S) in which aggregation was slowed relied on the HEK293 cell model, we examined the aggregation of mouse SOD1-G86R in cell culture. The WT and G86R variants of mouse SOD1 were compared with the G85R variant of human SOD1. Both mouse SOD1-G86R and human SOD1-G85R formed detergent-insoluble aggregates at similar propensities (Fig. 6A). Similar to human WT SOD1 (Fig. 1A), mouse WT SOD1 was not readily detected in the insoluble fraction (Fig. 6A). As expected, all three SOD1 variants were detected in the soluble fraction (Fig. 6B). These data indicate that amino acid sequence differences between human and mouse SOD1 modulate the requirement for cysteine at 111 in promoting aggregation. In the context of the mouse protein, a cysteine at 111 is not required, and the presence of serine does not reduce aggregation.

FIGURE 6.

Mouse SOD1-G86R aggregates in cell culture. Mutants were expressed in HEK293FT cells, and aggregate levels were determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” SDS-PAGE was performed in the presence of a reducing agent in an 18% Tris-glycine gel. Immunoblots were probed with m/hSOD1 antiserum. Experiments were replicated three times; a representative example is shown. A, P2, detergent-insoluble protein fraction (20 μg). B, S1, detergent-soluble protein fraction (5 μg). UT, untransfected cells.

To determine the extent to which disulfide-linked multimers occur in lysates from HEK293FT cells expressing human SOD1 with the A4V, G85R, and G93A natural fALS mutations, detergent extraction buffers were supplemented with iodoacetamide, a non-reversible sulfhydryl-blocking agent, as detergent-soluble and -insoluble fractions were isolated. When these fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE in the absence of reducing agents, most of the insoluble protein migrated at the size expected for monomeric SOD1 (Fig. 7A, lanes 3, 4, and 5). To a variable degree, a portion of the insoluble SOD1 in each cell lysate migrated at a higher than expected molecular weight (Fig. 7A). Distinct bands were detected at 40 kDa, which are a size (in this gel system) that is consistent with disulfide-linked dimers of SOD1. When the mutants expressed in cell culture were prepared in the absence of iodoacetamide and examined by SDS-PAGE with reducing agent, nearly all mutant protein detected in the insoluble and soluble fractions migrated at a position expected of monomeric protein (Fig. 7, C and D). Collectively these data indicate that, in the HEK293FT cell culture model, a portion of the insoluble protein forms intermolecular disulfide bonds, forming primarily structures dimeric in size, but a large portion of the SOD1 in the detergent-insoluble fraction is not involved in intermolecular disulfide bonding.

FIGURE 7.

Intermolecular disulfide bonding by SOD1 mutants in expressed cultured cells. FALS mutants (A4V, G85R, and G93A) were expressed in HEK293FT cells and detergent-extracted in buffers containing iodoacetamide (see “Experimental Procedures”). A and B, SDS-PAGE was performed in the absence of reducing agent in a 4–20% Tris-glycine gel. Immunoblots were probed with m/hSOD1 antiserum. Experiments were replicated four times; a representative example is shown. A, P2, detergent-insoluble protein fraction (20 μg). B, S1, detergent-soluble protein fraction (5 μg). C and D, the same sets of samples as depicted in A and B were analyzed by SDS-PAGE in the presence of a reducing agent. C, P2, detergent-insoluble protein fraction (20 μg). D, S1, detergent-soluble protein fraction (5 μg). Open arrowhead, dimer-sized SOD1 molecules. Closed arrowhead, monomeric SOD1 molecules. UT, untransfected cells.

In a previous study, Furukawa et al. (24) noted that extraction of tissues from symptomatic G93A mice in 0.5% SDS solubilized disulfide-cross-linked forms of mutant SOD1. To determine whether 0.5% SDS solubilizes all aggregated forms of mutant SOD1 in these mice, we used our extraction/centrifugation protocol, substituting 0.5% SDS for 0.5% Nonidet P-40 (see “Experimental Procedures”). Extraction of spinal cord tissues from asymptomatic WT and symptomatic G93A transgenic mice in buffers with 0.5% SDS and iodoacetamide, which irreversibly blocks free sulfhydryl residues, completely solubilized all mutant SOD1 that accumulated (Fig. 8A). No protein was detected in the high speed pellet after centrifugation (the detergent-insoluble fraction) (Fig. 8A, middle panel). In SDS-PAGE of these samples in the absence of reducing agent, high molecular weight SOD1 proteins were detected in the G93A tissue but not in WT SOD1 mice (Fig. 8A, left panel). When the soluble fraction was treated with reducing agent before SDS-PAGE, all of the disulfide bonds were broken, and only monomeric SOD1 was detected (Fig. 8A, right panel). As a positive control, the same spinal cord homogenates were extracted with buffers containing 0.5% Nonidet P-40 and were run in the presence of reducing agent (without iodoacetamide). As expected, the tissues from the symptomatic G93A mouse contained large amounts of mutant protein in the insoluble fraction (Fig. 8B, right panel, P2) with both WT and G93A SOD1 present in the soluble fractions (Fig. 8B, left panel, S1). Together these data indicate that, in a setting in which disulfide cross-links are preserved, ionic detergents are sufficient to disrupt aggregate structure. Hence disulfide cross-linking alone is not responsible for the maintenance of detergent-insoluble structures that are distinguished by sedimentation upon ultracentrifugation.

DISCUSSION

Our study sought to examine how disulfide bonds, formed between specific cysteine residues of mutant SOD1, may mediate the formation of detergent-insoluble, sedimentable structures (termed aggregates). From our findings, we conclude that disulfide cross-linking of mutant SOD1 is not critical in aggregate formation nor do these cross-links appear to be a sufficient bonding force in maintaining aggregate structure. By yet to be defined mechanisms, cysteine residues 6 and 111 were found to exert significant influence over mutant protein aggregation.

A critical element in considering our work is how protein aggregates are defined. In histologic studies of tissues, aggregates are usually defined by the formation of discernable inclusion body structures. However, in fALS mice, such structures are not necessarily prominent pathologic features (20, 21). Biochemically aggregates isolated from tissues and cells are defined by several criteria (for a review, see Ref. 35). In general, aggregates are derived from assemblies of monomeric protein that attain relatively high molecular weight (examples include filamentous aggregates as well as smaller oligomeric structures). In many cases, pathologic protein aggregates resist dissociation in detergent, and larger aggregates are of a size that allows for sedimentation upon centrifugation. In the fALS mice, previous work from our laboratory has shown that spinal cord tissues of symptomatic mice accumulate substantial levels of detergent-insoluble, sedimentable, mutant SOD1 (20, 21, 36). Thus, our study focused on the biochemistry of these sedimentable aggregates.

Previous work, from our group and others, has established that detergent-insoluble aggregates of mutant SOD1 that accumulate in spinal cords of fALS mice are extensively cross-linked by disulfide bonds (24, 26). Recent studies have investigated the role of disulfide bonding in SOD1 aggregation, and data reported to date have been interpreted as evidence that disulfide bond formation between mutant SOD1 proteins could either initiate oligomerization or provide the major bonding force to stabilize aggregate structures (24, 28, 29). Indeed one of the authors of the present study participated in a study suggesting a role for disulfide linkage in mutant SOD1 aggregation (26). However, through examination of multiple mutants and combinations of mutations, the present study demonstrates that the role of cysteine residues in SOD1 in modulating the aggregation of mutant SOD1 is complex and likely to involve mechanisms other than disulfide cross-linking.

First we found that SOD1 encoding fALS-linked mutations at cysteine residues 6, 111, or 146 aggregate when expressed in cell culture, indicating that the loss of any one of these cysteines does not block mutant protein aggregation. These findings, regarding cysteines 6 and 111, are in agreement with a study by Cozzolino et al. (28) that was published while this manuscript was in revision. Second we noted that cysteines 6 and 111 appear to play important roles in promoting SOD1 aggregate formation as mutant proteins that possess either one of these residues retained the ability to rapidly aggregate whereas proteins that retained only cysteines 57 or 146 did not rapidly aggregate (also see Ref. 28). Similar to Cozzolino et al. (28), we found that elimination of both cysteines 6 and 111 (most specifically by mutating cysteine 111 to serine) reduced or dramatically slowed aggregation. However, we now demonstrate that this outcome is unique to human SOD1. Mouse SOD encoding the equivalent of the human G85R mutation and that naturally encodes serine at position 111 retained a high propensity to aggregate in cell and mouse models. We also identified experimental mutants that retained only one cysteine residue while retaining a high propensity to aggregate; these mutants were incapable of forming disulfide-linked structures larger than dimers (see supplemental Fig. S1), and hence extensive cross-linking by disulfide bonding cannot be critical for aggregate formation or stability. Finally and most importantly, we identified an experimental SOD1 mutant lacking all cysteine residues (three of four replaced by fALS-linked mutations) that retained the capacity to rapidly aggregate. From this body of evidence, we conclude that if disulfide cross-linking has any role in promoting or stabilizing mutant SOD1 aggregation such cross-linking is not required and may not be of major importance. Although one could argue that these experimental mutants and the cell culture system do not reflect natural events, we demonstrated that aggregates of SOD1-G93A found in the spinal cords of symptomatic mice dissociate completely in 0.5% SDS despite extensive preservation of disulfide cross-linking. Collectively these data demonstrate that disulfide cross-linking is not responsible for the structure adopted by mutant SOD1 that accounts for sedimentation upon ultracentrifugation, a hallmark feature of SOD1 aggregates.

Cysteines 6 and 111 Modulate Aggregation of Mutant SOD1—Similar to a recent series of studies (24, 27–29), we found that cysteines 6 and 111 in human SOD1 play important roles in modulating mutant SOD1 aggregation. However, the C6G, C6F, and C111Y mutants each rapidly formed aggregates in our cell model, indicating that neither of these residues is indispensable. Although we identified experimental mutants in which the need for cysteine at any of the natural positions is obviated, some of our experimental mutants suggested important roles for cysteines 6 and 111 in promoting aggregation. Combining C6G and C111Y mutations (C6G/C111Y) or C6G and C6F with C111S (C6G/C111S and C6F/C111S) produced mutants with low propensity to aggregate. One of the most striking effects on aggregation was noted when the cysteine 111 to serine mutation was combined with the G85R mutation in human SOD1, producing a double mutant that failed to aggregate within 24 h, similar to wild-type SOD1. Cozzolino et al. (28) recently demonstrated that combining a C111S mutation with the A4V, G93A, and C146R fALS mutations produced similar reductions in aggregation. Collectively these studies implicate cysteine 111 as a potentially crucial residue in promoting aggregation. However, in mouse SOD1, position 111 is serine. Thus, the mouse SOD1-G86R animal, which develops motor neuron disease marked by hind limb paralysis, possesses an equivalent of our experimental human G85R/C111S mutant. In contrast to human SOD1, mouse SOD1-G86R readily formed detergentinsoluble, sedimentable species in both cell culture models and most importantly in the spinal cords of symptomatic mouse SOD1-G86R mice. Hence the effect of serine versus cysteine at position 111 on SOD1 aggregation appears to be dependent upon the species from which the protein is derived (mouse and human SOD1 differ in sequence at 27 positions).

Another key observation that led us to believe that structural features of cysteines 6 and 111 modulate aggregation rather than disulfide bonding is derived from the comparison of our two experimental mutants that alter all four cysteine residues. The C6G/C57S/C111Y/C146R variant showed an aggregation potential no different from WT SOD1, whereas the C6F/C57S/C111Y/C146R variant rapidly aggregated similar to SOD1-G85R. The simplest explanation for this outcome is that the phenylalanine at position 6 imparts an important structural feature to the protein that restores its ability to rapidly aggregate.

Structural Features of Cysteine 111—In most species, the amino acid homologous to position 111 is serine rather than cysteine; humans and chickens are the only species in which position 111 is occupied by cysteine (26). In crystal structures of human SOD1, position 111 is located in the Greek key loop near the dimer interface (2). Cysteine 111 is not obviously involved in crucial structural elements of the enzyme, but it is notable that serine is highly conserved at this position with the two exceptions noted above. Recent studies have demonstrated that cysteine 111 may strongly bind metal ions, including copper (37). Cysteine 111 may also bind other ligands such as glutathione, thioredoxins, or other molecules that utilize disulfide linkages to mediate binding (38, 39). A recent study by Fujiwara et al. (40) reported that cysteine 111 is a target for oxidative modification and that some of the mutant SOD1 that accumulates in pathologic structures in G93A mice is oxidatively modified at this position. Notably Cozzolino et al. (28) reported that modulating the redox potential of NSC-34 cells influenced mutant SOD1 aggregation. It is possible that mechanisms involving a modification of the cysteine residues, particularly 111, impart structural alterations in the protein to promote aggregation.

Disulfide Bonding in Mutant SOD1 Aggregation—Our analysis of mutant SOD1 aggregates formed in both cell culture and the G93A mouse model indicates that aggregates of SOD1-G93A in symptomatic mice appear to be dissociated (converted from structures that sediment upon ultracentrifugation to structures that do not) in 0.5% SDS despite retaining significant disulfide cross-linking. Thus, whatever role disulfide bonding plays in aggregate formation, such bonds are not sufficient to maintain the aggregate structure as a sedimentable entity.

We were initially surprised to find that 0.5% SDS was sufficient to solubilize (fractionate to high speed supernatant) mutant SOD1. In previous studies, using a filter-trap assay, we had interpreted the retention of significant fractions of mutant SOD1 in 0.22-μm cellulose acetate filters as evidence that mutant SOD1 aggregates are SDS-resistant (18). In light of our current study and the study by Furukawa et al. (24) described above, we now interpret the retention of mutant SOD1 in these filters as entrapment of disulfide-cross-linked lattices that persist after solubilization in SDS rather than retention of structures that are identical to the sedimentable species of mutant protein described here. In this latter scenario, the disulfide cross-links maintain an extended network of intermolecular interactions, some of which would be large enough to be retained in the filter. Importantly a disulfide-cross-linked network is distinct from the structures that are distinguished by resistance to solubilization in non-ionic detergent and sedimentation upon ultracentrifugation.

Prior studies of mutant SOD1 in tissues from G93A mice had identified high molecular weight structures in denaturing SDS-PAGE that were interpreted to represent SDS-resistant complexes (16, 41, 42). The SDS-resistant high molecular weight SOD1 seen in SDS-PAGE generally ranges in size from dimers to molecules of a mass no larger than relatively small oligomers (no more than 10–20 subunits). Such structures do not appear to possess sufficient mass to sediment in ultracentrifugation (see Fig. 8). We propose that these SDS-resistant structures that have been described in SDS-PAGE may largely represent covalently linked adducts to SOD1, formed by modifications such as ubiquitination or sumoylation, or may represent SOD1 proteins that are covalently cross-linked by mechanisms other than disulfide linkages (20). We have previously demonstrated high molecular weight forms of mutant SOD1 in denaturing SDS-PAGE analysis of detergent-insoluble, sedimentable structures (20). These high molecular weight, SDS-resistant SOD1 proteins are a relatively minor fraction of total insoluble protein. Notably a recent study of mutant SOD1 that fractionates into the Nonidet P-40-insoluble fraction demonstrated that the majority of the insoluble SOD1 displays a mass consistent with an unmodified monomer, which is in some manner assembled into higher order sedimentable structures (36).

Conclusions—We conclude that disulfide bonding is likely to be of limited importance in maintaining the structure of aggregated forms of mutant SOD1. Instead it appears that the aggregates are stabilized by molecular interactions that are dissociable by ionic detergent. We note that β-strand elements are a prominent feature of SOD1 and that these elements in the core β-barrel structure of the protein are aligned adjacent to one another forming numerous hairpin folds (2). The stacking of β-sheets is a characteristic feature of amyloids (43–47). In previous studies we have noted the appearance of amyloid-like structures (stained with Thioflavin-S) in tissues of some but not all fALS mouse models (20, 21). Whether fALS mutant SOD1 assembles into amyloid-like structures in vivo, however, is unclear. Notably in vitro, amyloid-like structures that are detergent-sensitive have been demonstrated for the H46R and S134N fALS mutants (48).

We are convinced by our data and that of others (24, 27–29) that cysteines 6 and 111 participate in some crucial component of human SOD1 aggregation; however, we believe that our study provides abundant evidence that the mechanism does not require disulfide cross-linking. Instead we propose that some other structural feature of these residues is critical in promoting aggregate formation. Whether modifications to cysteine residues, particularly cysteine 111, are critical in promoting human SOD1 aggregation is clearly a topic deserving further study. Similarly a better understanding of the structural features of human SOD1 aggregates and the role cysteine residues play in maintenance of such structures is required.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hilda Slunt Brown (University of Florida), Dr. Stephen P. Holloway (University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Center for Biomolecular Structure Analysis), and Ning Chan (Johns Hopkins University) for advice and assistance in generating the SOD1 expression constructs used in this study. We thank Mercedes Prudencio for thoughtful discussions and help in preparation of this manuscript. We thank our colleagues for thoughtful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant P01 NS049134 (a program project award to Drs. Joan S. Valentine, P. John Hart, D. R. B., and J. P. Whitelegge). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; SOD1, Cu,Znsuperoxide dismutase (superoxide dismutase 1); fALS, familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; WT, wild-type.

References

- 1.Rosen, D. R., Siddique, T., Patterson, D., Figlewicz, D. A., Sapp, P., Hentati, A., Donaldson, D., Goto, J., O'Regan, J. P., Deng, H. X., Rahmani, Z., Krizus, A., McKenna-Yasek, D., Cayabyab, A., Gaston, S. M., Berger, R., Tanzi, R. E., Halperin, J. J., Herzfeldt, B., Van den Bergh, R., Hung, W.-Y., Bird, T., Deng, G., Mulder, D. W., Smyth, C., Laing, N. G., Soriano, E., Pericak-Vance, M. A., Haines, J., Rouleau, G. A., Gusella, J. S., Horvitz, H. R., and Brown, R. H., Jr. (1993) Nature 362 59–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parge, H. E., Hallewell, R. A., and Tainer, J. A. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89 6109–6113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyons, T. J., Gralla, E. B., and Valentine, J. S. (1999) Met. Ions Biol. Syst. 36 125–177 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crapo, J. D., Oury, T., Rabouille, C., Slot, J. W., and Chang, L. Y. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89 10405–10409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller, G. A., Warner, T. G., Steimer, K. S., and Hallewell, R. A. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88 7381–7385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaarsma, D., Rognoni, F., van Duijn, W., Verspaget, H. W., Haasdijk, E. D., and Holstege, J. C. (2001) Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 102 293–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borchelt, D. R., Lee, M. K., Slunt, H. S., Guarnieri, M., Xu, Z. S., Wong, P. C., Brown, R. H., Jr., Price, D. L., Sisodia, S. S., and Cleveland, D. W. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91 8292–8296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potter, S. Z., and Valentine, J. S. (2003) J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 8 373–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valentine, J. S., and Hart, P. J. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 3617–3622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayward, L. J., Rodriguez, J. A., Kim, J. W., Tiwari, A., Goto, J. J., Cabelli, D. E., Valentine, J. S., and Brown, R. H., Jr. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 15923–15931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishida, C. R., Gralla, E. B., and Valentine, J. S. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91 9906–9910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ratovitski, T., Corson, L. B., Strain, J., Wong, P., Cleveland, D. W., Culotta, V. C., and Borchelt, D. R. (1999) Hum. Mol. Genet. 8 1451–1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiedau-Pazos, M., Goto, J. J., Rabizadeh, S., Gralla, E. B., Roe, J. A., Lee, M. K., Valentine, J. S., and Bredesen, D. E. (1996) Science 271 515–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiwari, A., and Hayward, L. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 5984–5992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reaume, A. G., Elliott, J. L., Hoffman, E. K., Kowall, N. W., Ferrante, R. J., Siwek, D. F., Wilcox, H. M., Flood, D. G., Beal, M. F., Brown, R. H., Jr., Scott, R. W., and Snider, W. D. (1996) Nat. Genet. 13 43–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston, J. A., Dalton, M. J., Gurney, M. E., and Kopito, R. R. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97 12571–12576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shinder, G. A., Lacourse, M. C., Minotti, S., and Durham, H. D. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 12791–12796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang, J., Xu, G., and Borchelt, D. R. (2002) Neurobiol. Dis. 9 139–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang, J., Xu, G., Gonzales, V., Coonfield, M., Fromholt, D., Copeland, N. G., Jenkins, N. A., and Borchelt, D. R. (2002) Neurobiol. Dis. 10 128–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, J., Slunt, H., Gonzales, V., Fromholt, D., Coonfield, M., Copeland, N. G., Jenkins, N. A., and Borchelt, D. R. (2003) Hum. Mol. Genet. 12 2753–2764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang, J., Xu, G., Li, H., Gonzales, V., Fromholt, D., Karch, C., Copeland, N. G., Jenkins, N. A., and Borchelt, D. R. (2005) Hum. Mol. Genet. 14 2335–2347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonsson, P. A., Ernhill, K., Andersen, P. M., Bergemalm, D., Brannstrom, T., Gredal, O., Nilsson, P., and Marklund, S. L. (2004) Brain 127 73–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe, Y., Yasui, K., Nakano, T., Doi, K., Fukada, Y., Kitayama, M., Ishimoto, M., Kurihara, S., Kawashima, M., Fukuda, H., Adachi, Y., Inoue, T., and Nakashima, K. (2005) Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 135 12–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furukawa, Y., Fu, R., Deng, H. X., Siddique, T., and O'Halloran, T. V. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 7148–7153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jonsson, P. A., Graffmo, K. S., Andersen, P. M., Brannstrom, T., Lindberg, M., Oliveberg, M., and Marklund, S. L. (2006) Brain 129 451–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang, J., Xu, G., and Borchelt, D. R. (2006) J. Neurochem. 96 1277–1288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banci, L., Bertini, I., Durazo, A., Girotto, S., Gralla, E. B., Martinelli, M., Valentine, J. S., Vieru, M., and Whitelegge, J. P. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 11263–11267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cozzolino, M., Amori, I., Pesaresi, M. G., Ferri, A., Nencini, M., and Carri, M. T. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 866–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niwa, J., Yamada, S., Ishigaki, S., Sone, J., Takahashi, M., Katsuno, M., Tanaka, F., Doyu, M., and Sobue, G. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 28087–28095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizushima, S., and Nagata, S. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res. 18 5322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gurney, M. E., Pu, H., Chiu, A. Y., Dal Canto, M. C., Polchow, C. Y., Alexander, D. D., Caliendo, J., Hentati, A., Kwon, Y. W., Deng, H. X., Chen, W., Zhai, P., Sufit, R. L., and Siddique, T. (1994) Science 264 1772–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ripps, M. E., Huntley, G. W., Hof, P. R., Morrison, J. H., and Gordon, J. W. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92 689–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong, P. C., Pardo, C. A., Borchelt, D. R., Lee, M. K., Copeland, N. G., Jenkins, N. A., Sisodia, S. S., Cleveland, D. W., and Price, D. L. (1995) Neuron 14 1105–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laemmli, U. K. (1970) Nature 227 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy, R. M. (2002) Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 4 155–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw, B. F., Lelie, H. L., Durazo, A., Nersissian, A. M., Xu, G., Chan, P. K., Gralla, E. B., Tiwari, A. J., Hayward, L. J., Borchelt, D. R., Valentine, J. S., and Whitelegge, J. P. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 8340–8350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe, S., Nagano, S., Duce, J., Kiaei, M., Li, Q. X., Tucker, S. M., Tiwari, A., Brown, R. H., Jr., Beal, M. F., Hayward, L. J., Culotta, V. C., Yoshihara, S., Sakoda, S., and Bush, A. I. (2007) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 42 1534–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schinina, M. E., Carlini, P., Polticelli, F., Zappacosta, F., Bossa, F., and Calabrese, L. (1996) Eur. J. Biochem. 237 433–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogawa, Y., Kosaka, H., Nakanishi, T., Shimizu, A., Ohoi, N., Shouji, H., Yanagihara, T., and Sakoda, S. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 241 251–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujiwara, N., Nakano, M., Kato, S., Yoshihara, D., Ookawara, T., Eguchi, H., Taniguchi, N., and Suzuki, K. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 35933–35944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krishnan, U., Son, M., Rajendran, B., and Elliott, J. L. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 287 201–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Son, M., Puttaparthi, K., Kawamata, H., Rajendran, B., Boyer, P. J., Manfredi, G., and Elliott, J. L. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 6072–6077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stromer, T., and Serpell, L. C. (2005) Microsc. Res. Tech. 67 210–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo, J. T., Wetzel, R., and Xu, Y. (2004) Proteins 57 357–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morimoto, A., Irie, K., Murakami, K., Ohigashi, H., Shindo, M., Nagao, M., Shimizu, T., and Shirasawa, T. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 295 306–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sawaya, M. R., Sambashivan, S., Nelson, R., Ivanova, M. I., Sievers, S. A., Apostol, M. I., Thompson, M. J., Balbirnie, M., Wiltzius, J. J., McFarlane, H. T., Madsen, A. O., Riekel, C., and Eisenberg, D. (2007) Nature 447 453–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thakur, A. K., and Wetzel, R. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 17014–17019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elam, J. S., Taylor, A. B., Strange, R., Antonyuk, S., Doucette, P. A., Rodriguez, J. A., Hasnain, S. S., Hayward, L. J., Valentine, J. S., Yeates, T. O., and Hart, P. J. (2003) Nat. Struct. Biol. 10 461–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.