Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Our goal was to identify antepartum, intrapartum, and infant risk factors for birth asphyxia mortality in a rural, low resource, population-based cohort in Southern Nepal.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data were collected prospectively during a cluster randomized, community-based trial evaluating the impact of newborn skin and umbilical cord cleansing on neonatal mortality and morbidity in Sarlahi, Nepal. 23,662 infants were born in study regions between September 2002 - January 2006. Multivariable regression modeling was performed to determine adjusted relative risk estimates of birth asphyxia mortality for antepartum, intrapartum, and infant risk factors.

RESULTS

Birth asphyxia deaths (9.7/1,000 live births) accounted for 30% of neonatal mortality. Antepartum risk factors for birth asphyxia mortality included low paternal education (relative risk [RR]: 1.69; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.23 to 2.33), Madeshi ethnicity (RR: 1.94; CI: 1.27 to 2.97) and primiparity (RR: 1.71; CI: 1.16 to 2.53). Facility delivery (RR: 1.89; CI: 1.19 to 3.00), maternal fever (RR: 2.02; CI: 1.26 to 3.23), maternal swelling of the face, hands or feet (RR: 1.40; CI: 1.01 to 1.96), and multiple births (RR: 4.77; CI: 2.78 to 8.20) were significant intrapartum risk factors for birth asphyxia mortality. Premature infants (<37 weeks) were at higher risk (RR: 2.28; CI: 1.69 to 3.09), and the combination of maternal fever and prematurity resulted in a synergistic elevation in risk for birth asphyxia mortality (RR: 7.12; CI: 4.25 to 11.90).

CONCLUSIONS

Maternal infections, prematurity, and multiple births are important risk factors for birth asphyxia mortality in the low-resource, community-based setting. Low socioeconomic status is highly associated with birth asphyxia and the mechanisms leading to mortality need to be further elucidated. The interaction between maternal infections and prematurity may be an important target for future community-based interventions to reduce the global impact of birth asphyxia on neonatal mortality.

Keywords: asphyxia neonatorum, risk factors, mortality, neonatal, Nepal

INTRODUCTION

Birth asphyxia is defined by the World Health Organization as “the failure to initiate and sustain breathing at birth.”1 Accurate estimates of the proportion of neonatal mortality due to birth asphyxia are limited by the lack of a consistent definition for use in community-based settings and the absence of vital registration in communities where the majority of neonatal deaths occur. Hospital-based studies in Nepal2 and South Africa3 estimated that birth asphyxia accounted for 24% and 14% of perinatal mortality, respectively. However, these may substantially underestimate the burden in rural areas, where early deaths, most of which occur at home, are more likely to be under-reported.4 In rural regions of Uttar Pradesh5 and Maharashtra6 states of India, 23% and 25% of neonatal mortality was attributed to birth asphyxia, respectively. Globally, hypoxia of the newborn (“birth asphyxia”) or the fetus (“fresh stillbirth”) is estimated to account for 23% of the 4 million neonatal deaths7 and 26% of the 3.2 million stillbirths each year.8, 9 An estimated 1 million children who survive birth asphyxia live with chronic neuro-developmental morbidities, including cerebral palsy, mental retardation, and learning disabilities.10

Definitions of birth asphyxia designed for use in hospital-based settings require evaluation of neonatal umbilical cord pH, Apgar scores, neurological clinical status, and markers of multi-system organ function,11 and are not feasible for community settings.12 Given that the majority of neonatal deaths occur in the home without medical supervision, community-based definitions must rely on data gathered from verbal autopsy methods and utilize more general symptom and sign-based algorithms. For example, the National Neonatology Forum of India has defined birth asphyxia as “gasping and ineffective breathing or lack of breathing at one minute after birth.”13 Such sign-based definitions are not, however, implemented consistently and varying study-specific definitions may affect estimation of the proportion of neonatal deaths attributed to birth asphyxia.

Risk factors for birth asphyxia in hospital-based settings in developing countries have been categorized into antepartum, intrapartum, and infant/postnatal characteristics (Table 1). Hospital and home-based risk factors for birth asphyxia may be similar but such data are entirely lacking.

TABLE 1.

Antepartum, Intrapartum, and Infant Risk Factors for Birth Asphyxia Previously Reported from Hospital-based Studies

| Antepartum Risk Factors |

| Primiparity 31, 44 |

| Maternal fever 29 |

| Pregnancy induced hypertension 31, 32 |

| Anemia 29 |

| Antepartum hemorrhage 29, 31, |

| History of prior neonatal death 31 |

| Intrapartum Risk Factors |

| Malpresentation 3, 29, 32 |

| Prolonged labor 32, 33 |

| Meconium stained amniotic fluid 3, 29, 31, 33 |

| Pre-eclampsia 29 |

| Premature rupture of membranes 29 |

| Oxytocin augmentation of labor 29 |

| Umbilical cord prolapse 3, 32 |

| Infant/Postnatal Factors |

| Prematurity 30 |

| Low birth weight 29, 45 |

| Intrauterine growth restriction 32, 44 |

In this study, we identify risk factors for birth asphyxia among newborns of rural Sarlahi District, Nepal, from data collected prospectively within the context of a large community-based trial of the impact of chlorhexidine cleansing of newborn skin and umbilical cord on neonatal morbidity and mortality.14, 15

METHODS

Data Collection

The data for this study were collected from 2002-2006 by the Nepal Nutrition Intervention Project, Sarlahi (NNIPS), Kathmandu, Nepal.14, 15 Study procedures have been reported in detail previously.14, 15 Briefly, pregnant women were identified during mid-pregnancy, the study was explained, and oral consent obtained. All women received albendazole (400 mg), iron-folic acid, and vitamin A supplementation, and health education on prenatal nutrition, infant thermal care, and hygienic umbilical cord care. Data were recorded on socioeconomic status, household structure, and maternal reproductive history.

Newborns were randomized within clusters [n=413 sectors, identified based on the population that one local female worker could service, approximately 40 to 50 households] in a factorial design to one of two full body skin cleansing regimens (0.25% chlorhexidine or placebo) 15 and subsequently, within each of these two groups, to one of three cord cleaning regimens (umbilical stump cleansing with 4% chlorhexidine, cleansing with soap and water, or dry cord care).14 A comparative phase from September 2002-March 2005 was followed by a second period during which all infants received the beneficial chlorhexidine cleansing interventions, upon recommendation of the trial’s Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

Data regarding maternal report of morbidity before, during and after childbirth was collected. Newborns were visited up to 11 times (days 1-4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 21, and 28) by study area coordinators and assessed for vital status and symptoms and signs of morbidity. Gestational age was estimated from two maternal reports (at the time of pregnancy registration and at first assessment after delivery) of time since last menstrual period. Verbal autopsies were conducted soon after a neonatal death (median time: 1.5 days, 92% within 24 hours of death) by supervisory workers who were trained in verbal autopsy techniques and had 3-12 years experience in conducting verbal autopsies in this setting. The verbal autopsy questionnaire was based on the World Health Organization standard verbal autopsy form16 with minor modifications.17

Case Definition of Birth Asphyxia

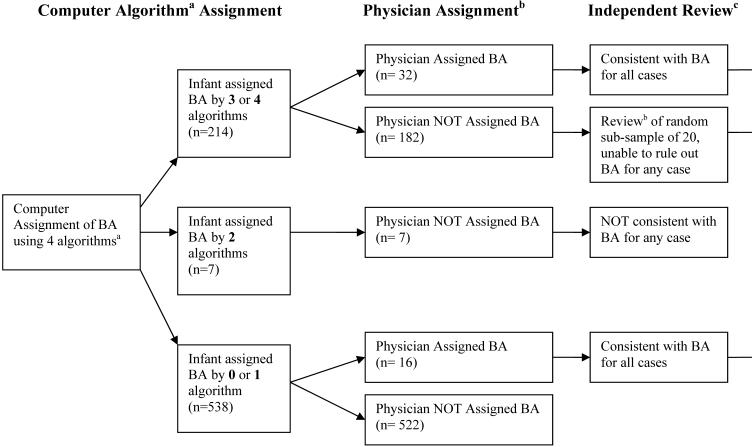

Four verbal autopsy-based definitions (i.e. algorithms) of birth asphyxia were identified in the literature and are reported in three publications: 1) the World Health Organization Standard Verbal Autopsy Methods (definitions 3 and 4),16 Baqui et al,18 and the Nepal Newborn Washing Study15 The algorithms contained varying combinations of clinical symptoms, including timing of death, crying at birth, breathing at birth, presence of convulsions, and sucking at birth, and are shown in Figure 1. Each of the four algorithms was applied to the 759 neonatal deaths to determine whether or not the death was attributable to birth asphyxia. As computer-algorithmic approaches to verbal autopsy data often result in multiple potential causes of death, a standard hierarchal approach was applied19 to identify and exclude deaths potentially attributable to neonatal tetanus or congenital malformations [confirmed through direct physician (RKA, SKK) assessment in Nepal, and further review by the study investigators (ACL, LCM, GLD), of the open narrative portion of the verbal autopsy provided by care-takers in the household]. Premature infants were not excluded given the overlapping clinical symptoms between premature and asphyxiated infants.

Figure 1.

Assignment of Birth Asphyxia (BA) as Cause of Neonatal Death

a Algorithm 1 (WHO-316): Infant was not able to cry after birth and either (not able to breathe after birth or not able to suckle normally after birth). Algorithm 2 (WHO-416): Infant was not able to cry after birth and either (with convulsions/spasms or not able to suckle normally after birth). Algorithm 3 (Baqui et al18): Infant died in the first 7 days of life and either (was not able to cry at birth, not able to breathe at birth, or unable to suckle normally at birth). Algorithm 4 (Newborn Washing Study15): Infant died in the first 7 days of life, was not able to cry at birth, and either (not able to breathe at birth, unable to suckle normally at birth, or with convulsions).

b Local Nepali Physician (RKA, SKK) review of verbal autopsy interview and open verbatim histories to assign cause of death

c Investigators (ACL, GLD, LCM) review of open verbatim histories to verify cause of death

The final cause of death assignment to birth asphyxia was based on an assessment of the level of concordance of the four algorithms, as well as further local physician ascertainment of cause of death and study investigator review of the open narrative accounts of death (Figure 1). These methods are described in greater detail in a separate report (ACC Lee, unpublished data). All neonatal deaths meeting 3 or 4 of the definitions (n=214) were assigned as birth asphyxia deaths. For those meeting 2 or fewer definitions, an additional 16 infants were identified as birth asphyxia deaths, bringing the total to 230 (30%) of the 759 total neonatal deaths. Of the 230 birth asphyxia deaths, 70 infants (30%) also met verbal autopsy criteria for prematurity (defined as “being born early”).

Statistical Analysis

The clinical characteristics of newborns in the study were analyzed with simple descriptive statistics and compared among 1) birth asphyxia deaths, 2) alternate causes of death, and 3) surviving infants, using chi-squared tests for categorical data and analysis of variance for continuous data. Risk factors for birth asphyxia mortality were grouped into antepartum, intrapartum, and postnatal/infant variables. Certain intrapartum risk factors were assessed by maternal self-report of symptoms in the 7 days before childbirth: “high fever” indicative of potential maternal infection, “bleeding from the vagina” for antepartum hemorrhage, “swelling of the hands, face, or feet” and “convulsions” for potential pre-eclampsia or eclampsia, “hours the labor pains lasted” for determining length of labor (prolonged labor defined as >24 hours in primiparous and >12 hours in multiparous mothers),20 “hours before delivery the water broke” for establishing length of rupture of membranes (prolonged rupture of membranes defined as >24 hours), and “color of the water” for assessing meconium staining. For each potential risk factor, the risk ratio (RR) for birth asphyxia death was calculated in bivariate analysis utilizing log binomial regression. Risk factors that were associated with birth asphyxia death with a p-value < 0.05 were considered for testing in the multivariate models.

Multivariate models were first generated separately for antepartum, intrapartum, and infant variables. Risk factors identified in the bivariate analyses were further evaluated in the multivariate models if they were associated with mortality after adjustments and/or substantially confounded the relationship between birth asphyxia mortality and other risk factors. Exceptions were maintained and variables included that have been established as important risk factors in prior studies; for example, the antepartum variables maternal age20, 21 and literacy22 (defined as the ability to read and write a simple letter). The multivariate model which focused on intrapartum risk factors included only those that temporally preceded the asphyxial event. For example, we excluded actions including resuscitative measures, assisted delivery, injections, and C-section that may have been undertaken as a result of labor complications potentially related to birth asphyxia. The intrapartum model included all significant (p < 0.05) covariates meeting this criterion, given that each was a well-established risk factor for asphyxia in hospital-based studies. The postnatal/infant model included all significant covariates without substantial missing data.

More comprehensive models combining antepartum, intrapartum, and infant variables were also developed. Interaction was tested between prematurity and specific intrapartum risk factors (maternal fever, swelling, vaginal bleeding, and prolonged rupture of membranes). Stratified analysis was performed for premature vs. full-term infants. The treatment effects of chlorhexidine skin and umbilical cord cleansing was explored both by intention to treat as well as actual treatment received.

In all models, standard errors were adjusted for non-independence of events for mothers contributing more than one child to the cohort. Co-linearity was inspected and in the case of substantial between-variable correlation, only the most significant variable was added to the model. STATA 9.0 (StatCorp LP, College Station, Texas) was used to conduct all analyses.

The study was approved by the Nepal Health Research Council (Katmandu, Nepal) and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Committee on Human Research (Baltimore, MD). The study was registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00109616).

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

Between September 2002-January 2006, there were 23,662 live births and 759 neonatal deaths in the study area. The overall characteristics of the study population have been described previously.14 The majority (20,295/22,364 [91%]) of infants were born in the nuclear family home, maiti (maternal home), or outdoors. The overall prevalence of low birth weight was 29.8% (6,784/22,762, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 29.2 to 30.4). Verbal autopsies were completed on 750/759 (99%) of the neonatal deaths.

The incidence of birth asphyxia was 9.7 deaths (n=230) per 1,000 live births (95% CI: 8.5 to 10.9; proportionate mortality 30.3%). Asphyxiated infants were of lower birth weight and gestational age (mean 2.22 kg, 37.1 weeks, respectively) than the surviving infants (mean 2.71 kg, 39.3 weeks, respectively), and died at an earlier age than those dying from other causes (median: 0.46 vs. 2.96 days) (Table 2). Asphyxiated infants had delayed onset of breathing, poor movement and color, and an increased frequency of convulsions. The median age at death due to birth asphyxia was 11 hours; 158 (69%) and 228 (99%) of such deaths occurred within the first 1 and 7 days of life, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Asphyxiated Infants, Non-Birth Asphyxia Deaths, and Surviving Infants

| Infant Characteristic | Birth Asphyxia Deaths | Non-Birth Asphyxia Deaths | Surviving Infants | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. of infants | 230 | 532 | 22,900 | |

| Place of Deliverya, n(%) | 0.00 | |||

| Home | 143 (64) | 347 (71) | 15,798 (73) | |

| Maiti (Maternal home) | 40 (18) | 73 (15) | 3,624 (17) | |

| Hospital/clinic | 35 (16) | 57 (12) | 1,977 (9) | |

| On way to clinic/outdoors | 6 (3) | 12 (3) | 252 (1) | |

| Birth weightb, kg | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.22 (0.67) | 2.14 (0.62) | 2.71 (0.43) | 0.00 |

| Gestational Agec, weeks | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 37.1 (4.30) | 36.73 (4.08) | 39.30 (2.40) | 0.00 |

| Category, n(%) | 0.00 | |||

| <34 | 50 (22) | 246 (46) | 329 (1) | |

| 34-37 | 43 (19) | 119 (22) | 3,650 (16) | |

| 37-42 | 115 (50) | 129 (24) | 16,050 (70) | |

| >42 | 22 (10) | 38 (7) | 2,858 (13) | |

| Sexd, n(%) | 0.08 | |||

| Male | 135 (59) | 267 (50) | 11,793 (52) | |

| Time to Deathe, days | ||||

| Median (range) | 0.46 (0.001, 8.0) | 2.96 (0.001, 33.7) | ||

| Signs of Injuryf, n(%) | 0.00 | |||

| Bleeding or bruising | 8 (4) | 15 (3) | 227 (1) | |

| Time to First Breathg, minutes | 0.00 | |||

| <1 | 61 (27) | 375 (82) | 18,094 (84) | |

| 2-5 | 40 (17) | 50 (11) | 2,145 (10) | |

| 6-9 | 21 (9) | 12 (3) | 287 (1) | |

| 10-15 | 23 (10) | 7 (2) | 328 (2) | |

| >15 | 58 (25) | 16 (4) | 561 (3) | |

| Infant Movement after birthh | 0.00 | |||

| No movement | 192 (87) | 59 (13) | 1,337 (6) | |

| Weak movement | 24 (11) | 141 (30) | 2,935 (14) | |

| Normal movement | 5 (2) | 266 (57) | 16,855 (80) | |

| Infant Colori | 0.00 | |||

| Red uniformly | 154 (67) | 412 (90) | 19,818 (95) | |

| Red except limbs | 4 (2) | 2 (0.4) | 375 (2) | |

| Blue, gray, or pale | 58 (25) | 42 (9) | 602 (3) | |

| Infant convulsionsj | 0.00 | |||

| Convulsions | 9 (4) | 11 (2) | 72 (0.3) |

A total of 1,298 were missing place of delivery data.

A total of 900 were missing birth weight data.

A total of 13 were missing gestational age data.

None were missing gender data.

None of the 762 deaths were missing age at death data.

A total of 1,482 were missing injury data.

A total of 1,584 were missing time at first breath data.

A total of 1,848 were missing movement at birth data.

A total of 2,195 were missing infant color at birth data.

A total of 1,727 were missing convulsion data.

Bivariate Analysis

Antepartum Risk Factors

Infants of mothers aged 20-29 years old were at lower risk for birth asphyxia mortality compared to infants of young mothers (<20 years) (Table 3). Birth asphyxia risk decreased significantly with increasing maternal education (relative risk [RR]: 0.57; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.40 to 0.83), maternal literacy (RR: 0.54; 95% CI 0.37 to 0.77), paternal education (>10 years, RR: 0.44; 95% CI: 0.29 to 0.68), and paternal literacy (RR: 0.52; 95% CI 0.40 to 0.69). Newborns of Madeshi ethnicity (“people from the plains”) had a 2.51 (95% CI: 1.71 to 3.68) times increased risk versus those of Pahadi ethnicity (“people from the hills”). Infants of primiparous women carried a higher risk for birth asphyxia mortality (RR: 1.74; 95% CI: 1.33 to 2.28), whereas history of a prior child death did not significantly predict birth asphyxia mortality (RR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.70 to 1.40).

TABLE 3.

Bivariate Analysis of Antepartum Risk Factors for Birth Asphyxia (BA) Mortality

| Antepartum Risk Factor | BA Cases | Total n | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age, years | |||

| < 20 | 79 | 5,989 | 1 (ref) |

| 20-24 | 85 | 9,396 | 0.69 (0.51 to 0.93) * |

| 25-29 | 37 | 5,159 | 0.54 (0.36 to 0.81)** |

| 30-34 | 21 | 2,156 | 0.74 (0.45 to 1.21) |

| > 35 | 8 | 950 | 0.64 (0.31 to 1.32) |

| Maternal Literacy | |||

| Illiterate | 194 | 17,569 | 1 (ref) |

| Literate | 36 | 6,081 | 0.54 (0.37 to 0.77) ** |

| Maternal Education | |||

| No education | 195 | 17,988 | 1 (ref) |

| Any education | 23 | 3,786 | 0.57 (0.4 to 0.83) ** |

| Maternal Occupation | |||

| Home | 201 | 19,940 | 1 (ref) |

| Farmer | 10 | 2,120 | 0.47 (0.25 to 0.88) * |

| Laborer | 16 | 1,278 | 1.24 (0.69 to 2.23) |

| Business | 2 | 182 | 1.09 (0.27 to 4.36) |

| Private | 1 | 76 | 1.31 (0.19 to 9.19) |

| Paternal Literacy | |||

| Illiterate | 137 | 10,308 | 1 (ref) |

| Literate | 93 | 13,329 | 0.52 (0.40 to 0.69) ** |

| Paternal Education, years | |||

| None | 143 | 10,939 | 1 (ref) |

| 1-10 | 62 | 8,086 | 0.59 (0.43 to 0.79) ** |

| > 10 | 25 | 4,382 | 0.44 (0.29 to 0.68) ** |

| Paternal Occupation | |||

| Farmer | 96 | 10,359 | 1 (ref) |

| Laborer | 99 | 7,882 | 1.36 (1.02 to 1.8) * |

| Business | 26 | 2,908 | 0.96 (0.61 to 1.52) |

| Private | 8 | 1,713 | 0.50 (0.25 to 1.03) |

| Caste | |||

| Higher caste (Brahmin, Chetri) | 24 | 3,074 | 1 (ref) |

| Lower caste (Vaishya, Shudra, Muslim) | 196 | 20,185 | 1.24 (0.81 to 1.90) |

| Ethnic Group | |||

| Pahadi | 30 | 6,627 | 1 (ref) |

| Madeshi | 189 | 16,646 | 2.51 (1.71 to 3.68) ** |

| Parity | |||

| ≥ 1 prior liveborn | 145 | 17,704 | 1 (ref) |

| 0 prior liveborn | 85 | 5,955 | 1.74 (1.33 to 2.28) ** |

| History of Child Death | |||

| No prior child death | 183 | 18,786 | 1 (ref) |

| ≥1 child death | 47 | 4,873 | 0.99 (0.70 to 1.40) |

| Electricity | |||

| No Electricity | 168 | 17,611 | 1 (ref) |

| Electricity | 50 | 5,662 | 0.95 (0.68 to 1.28) |

0.01< p ≤ 0.05

p ≤ 0.01

Intrapartum Risk Factors

While the majority of births in this region took place at home, the deliveries that took place “on the way to clinic” (RR: 2.43; 95% CI:1.09 to 5.43) and in medical facilities (RR: 1.85; 95% CI: 1.27 to 2.68) were associated with a higher risk of birth asphyxia mortality (Table 4). Of maternal symptoms self-reported within 7 days before childbirth, fever (RR: 3.30; 95% CI: 2.15 to 5.07), vaginal bleeding (RR: 2.00; 95% CI: 1.23 to 3.27), “swelling of the hands, face, or feet” (RR: 1.78; 95% CI: 1.33 to 2.37), convulsions (RR: 4.74; 95% CI: 1.80 to 12.46), prolonged labor (RR: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.00 to 1.73) and prolonged rupture of membranes (RR: 1.83; 95% CI: 1.22 to 2.76) were significantly associated with increased risk for birth asphyxia mortality. Multiple births (twin or triplet) were strongly related to birth asphyxia mortality (RR: 5.73; 95% CI: 3.38 to 9.72).

TABLE 4.

Bivariate Analysis of Intrapartum and Infant Risk Factors for Birth Asphyxia (BA) Mortality

| Intrapartum Risk Factor | BA Cases | Total n | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place of Delivery | |||

| Home | 183 | 20,025 | 1 (ref) |

| Health Facility (Hospital or Clinic) | 35 | 2,069 | 1.85 (1.27 to 2.68) ** |

| On way to clinic/outdoors | 6 | 270 | 2.43 (1.09 to 5.43) * |

| Maternal Fever § | |||

| No fever | 200 | 21,577 | 1 (ref) |

| Fever | 24 | 784 | 3.3 (2.15 to 5.07) ** |

| Vaginal Bleeding § | |||

| No bleeding | 208 | 21,464 | 1 (ref) |

| Bleeding | 17 | 876 | 2.00 (1.23 to 3.27) ** |

| Swelling of face, hands, or feet § | |||

| No swelling | 162 | 18,348 | 1 (ref) |

| Swelling of face, hands, or feet | 63 | 4,019 | 1.78 (1.33 to 2.37) ** |

| Convulsions § | |||

| No convulsions | 221 | 22,263 | 1 (ref) |

| Convulsions | 4 | 85 | 4.74 (1.80 to 12.46) ** |

| Prolonged Labor | |||

| Labor <24 hours primiparous or <12 hours multiparous | 149 | 16,117 | 1 (ref) |

| Labor >24 hours primiparous or > 12 hours multiparous | 75 | 6,172 | 1.31 (1.00 to 1.73) * |

| Multiple pregnancy | |||

| Singleton | 211 | 23,296 | 1 (ref) |

| Multiple birth | 19 | 366 | 5.73 (3.38 to 9.72) ** |

| Rupture of membranes | |||

| ROM<24 hours | 194 | 20,577 | 1 (ref) |

| ROM>24 hours | 27 | 1,564 | 1.83 (1.22 to 2.76) ** |

| Amniotic fluid | |||

| Clear | 126 | 14,595 | 1 (ref) |

| Green | 1 | 88 | 1.32 (0.19 to 9.32) |

| Red | 56 | 4,100 | 1.58 (1.14 to 2.19) ** |

| Infant Risk Factors | |||

| Birth weight, kg | |||

| <2 | 20 | 1,146 | 11.88 (6.09 to 23.14) ** |

| 2.0-2.4 | 10 | 5,638 | 1.21 (0.54 to 2.69) |

| 2.5-2.9 | 15 | 10,211 | 1 (ref) |

| >3.0 | 6 | 5,767 | 0.71 (0.27 to 1.82) |

| Gestational age, weeks | |||

| <34 | 50 | 498 | 14.33 (10.31 to 19.91) ** |

| 34-37 | 43 | 3,822 | 1.61 (1.13 to 2.27) ** |

| 37-42 | 115 | 16,411 | 1 (ref) |

| >42 | 22 | 2,918 | 1.07 (0.69 to 1.67) |

| Infant sex | |||

| Male | 135 | 12,195 | 1 (ref) |

| Female | 95 | 11,467 | 0.75 (0.58 to 0.97) * |

0.01< p ≤ 0.05

p ≤ 0.01

Symptoms reported within 7 days prior to delivery

Infants with “green” (presumably meconium stained) amniotic fluid had a non-significant greater risk of birth asphyxia (RR: 1.32; 95% CI: 0.19 to 2.16), however, the sample size was small and precision of the estimate was low. “Red” amniotic fluid carried a 1.58 (95% CI: 1.15 to 2.16) times increased risk; however, this was clinically difficult to distinguish from vaginal bleeding and was therefore not included in the final multivariate models.

Infant Factors

A substantial proportion of birth weight information was missing on the birth asphyxia cases (179/230, 78%) because death occurred prior to the first visit by study staff (median time to visit for birth weight measurement, 19 hours). The risk for birth asphyxia mortality was 11.88 (95% CI: 6.09 to 23.14) fold higher in the lowest weight category of < 2 kg as compared to the 2.5-2.9 kg weight category (Table 4). However, due to the considerable differential missing data for birth asphyxia cases, birth weight was not included in the final multivariate model. Prematurity carried a substantially higher risk of birth asphyxia mortality, with gestational age 34-37 weeks increasing the risk by a factor of 1.61 (95% CI: 1.13 to 2.27) and gestational age <34 weeks increasing risk by a factor of 14.33 (95% CI: 10.31 to 19.91). In contrast to hospital-based studies,20 post-term infants were not at greater risk for birth asphyxia.

There was no significant treatment effect on birth asphyxia mortality for infants who received either the full body skin cleansing (chlorhexidine vs. placebo wipes, RR: 0.87; 95% CI 0.57 to 1.31) or umbilical cord cleansing treatments (chlorhexidine vs. dry cord care, RR: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.40 to 1.82). A large proportion of the infants allocated to treatment who died from birth asphyxia did not live long enough to receive either skin cleansing (135/230, 59%) or umbilical cord cleansing (179/230, 78%). Because there was not a significant difference in risk for mortality due to birth asphyxia between the infants who actually received the skin cleansing with chlorhexidine vs. placebo, or among infants in the chlorhexidine cord cleansing group or soap-and-water cleansing group vs. placebo, treatment allocation was not included in the multivariate models.

Multivariate Models

Antepartum Risk Factors

Maternal and paternal literacy, education, and occupation were correlated socioeconomic covariates; paternal education was the most significant risk factor, associated with a 41% lower birth asphyxia risk (any vs. none, adjusted RR: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.43 to 0.81, final model) (Table 5). Maternal literacy was the strongest maternal socioeconomic indicator and thus retained in the antepartum model to control for maternal socioeconomic status, although it was not significant after adjustment (RR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.50 to 1.25). Ethnicity (RR: 1.94; 95% CI: 1.27 to 2.97) remained significant after controlling for the other socioeconomic indicators.

TABLE 5.

Multivariate Models of Antepartum, Intrapartum, and Infant Risk Factors for Birth Asphyxia Mortality

| Model 1 (n=23,023) | Model 2 (n=22,095) | Model 3 (n=21,491) | Final Model (n=21,491) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antepartum risk factor | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI) |

| Maternal Age, years | ||||

| <20 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| 20-24 | 1.01 (0.68 to 1.50) | 1.01 (0.68 to 1.50) | 1.03 (0.69 to 1.54) | |

| 25-29 | 0.78 (0.47 to 1.27) | 0.74 (0.45 to 1.21) | 0.75 (0.46 to 1.24) | |

| 30-34 | 0.97 (0.53 to 1.75) | 0.80 (0.43 to 1.49) | 0.83 (0.44 to 1.54) | |

| >35 | 0.85 (0.39 to 1.87) | 0.65 (0.28 to 1.54) | 0.65 (0.27 to 1.54) | |

| Maternal Literacy | ||||

| Illiterate | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| Literate | 0.83 (0.53 to 1.29) | 0.78 (0.50 to 1.24) | 0.79 (0.50 to 1.25) | |

| Paternal Education | ||||

| No Education | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| Any Education | 0.58 (0.42 to 0.80) ** | 0.59 (0.43 to 0.81) ** | 0.59 (0.43 to 0.81) ** | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Pahmadi | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| Madeshi | 2.15 (1.43 to 3.24) ** | 1.93 (1.27 to 2.95) ** | 1.94 (1.27 to 2.97) ** | |

| Parity | ||||

| Multiparous | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| Primiparous | 1.93 (1.33 to 2.80) ** | 1.69 (1.15 to 2.49) ** | 1.71 (1.16 to 2.53) ** | |

| Intrapartum risk factor | ||||

| Place of Delivery | ||||

| Home | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| Facility | 1.51 (1.00 to 2.27) ** | 1.90 (1.19 to 3.02) ** | 1.89 (1.19 to 3.00) ** | |

| Maternal Fever | ||||

| No fever | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| Fever | 2.75 (1.78 to 4.25) ** | 2.02 (1.26 to 3.23) ** | 0.84 (0.31 to 2.28) § | |

| Maternal Swelling | ||||

| No swelling | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| Swelling of hands, face, or feet | 1.45 (1.05 to 1.99) * | 1.39 (1.00 to 1.95) * | 1.40 (1.01 to 1.96) * | |

| Convulsions | ||||

| No convulsions | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| Convulsions | 1.22 (0.29 to 5.16) | 0.99 (0.24 to 4.19) | 1.00 (0.25 to 3.98) | |

| Vaginal Bleeding | ||||

| No Bleeding | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| Bleeding | 1.61 (0.96 to 2.70) | 1.63 (0.95 to 2.81) | 1.62 (0.95 to 2.77) | |

| Rupture of Membranes | ||||

| ROM < 24 hours | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| ROM > 24 hours | 1.39 (0.90 to 2.14) | 1.32 (0.83 to 2.10) | 1.28 (0.80 to 2.04) | |

| Multiple Birth | ||||

| Singleton | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| Twin or Triplet | 5.23 (3.00 to 9.13) ** | 4.90 (2.84 to 8.43) ** | 4.77 (2.78 to 8.20) ** | |

| Infant risk factor | ||||

| Gestational Age | ||||

| Full-term >37 weeks | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Premature <37weeks | 2.56 (1.95 to 3.37)** | 2.28 (1.69 to 3.09)¶, ** | ||

| Infant Sex | ||||

| Male | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Female | 0.71 (0.54 to 0.93) * | 0.71 (0.54 to 0.93) * | ||

| Interaction | ||||

| Maternal fever × Prematurity | 3.70 (1.18 to11.60) £, * | |||

0.01< p ≤0.05

p ≤0.01

Relative Risk of maternal fever in full term infants

Relative Risk of prematurity in infants without exposure to maternal fever

Exponentiated Interaction term coefficient; p=0.02

Parity confounded the relationship between maternal age and birth asphyxia mortality. While maternal age was not significantly associated with birth asphyxia in the final model (Table 5), the risk was difficult to disassociate from parity because age and parity were strongly correlated at low maternal age. Given the recent findings of prematurity and low birth weight mediating risk of neonatal mortality in adolescent mothers (V Sharma, personal communication, 2007), this relationship was further explored and found applicable to birth asphyxia deaths. Among adolescent mothers < 16 years old, the unadjusted excess risk for birth asphyxia mortality was 88% (reference 20-24 years, RR: 1.88; 95% CI: 0.83 to 4.25). After adjusting for antepartum and intrapartum risk factors (including parity, excluding prematurity), the excess risk was reduced to 22% (RR: 1.22; 95% CI: 0.51 to 2.95). Prematurity further attenuated the birth asphyxia risk attributed to adolescent maternal age by an additional 7% (RR: 1.15; 95% CI: 0.49 to 2.74). The relationship of birth weight was not explored given the differential missing data for birth asphyxia deaths.

Intrapartum Risk Factors

The increased risk for birth asphyxia mortality associated with facility-based births remained significant after controlling for intrapartum complications, socioeconomic and infant factors (RR: 1.89, 95% CI: 1.19 to 3.00) (Table 5). Maternal fever carried a higher risk for birth asphyxia mortality (RR: 2.02; 95% CI: 1.26 to 3.23, model 3), and the effect was significantly modified by prematurity (full term RR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.31 to 2.28, final model; premature RR: 3.11, 95% CI: 1.78 to 5.46). Maternal swelling (RR: 1.40; 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.96) was associated with elevated asphyxia risk, while prolonged rupture of membranes and vaginal bleeding resulted in a 28% and 62% non-significant increased risk after controlling for the remaining covariates. The risk of prolonged labor was attenuated after adding intrapartum covariates to the model. Prolonged labor may act as an intermediate variable, mediating the effects of other factors such as primiparity and multiple birth,23 and was therefore not included in the multivariate models.

Infant Risk Factors

Gestational age was modeled as a continuous, categorical and dichotomous variable in initial univariate analysis; however, the choice of scale did not significantly affect the coefficients of the other covariates in the development of the multivariate model. Given that a range of uncertainty exists for gestational age estimation by LMP,24 gestational age was categorized as dichotomous, premature (< 37 weeks gestation) vs. full term (≥ 37 weeks), in the final multivariate model. Prematurity was associated with a 2.28-fold (95% CI: 1.69 to 3.09) higher birth asphyxia risk after adjustment for the other covariates (Table 4). Sub-analysis restricting the cohort to full term infants yielded similar effects and associations of risk factors as the entire cohort.

Interaction

Maternal fever significantly modified the effect of prematurity on birth asphyxia mortality (exponentiated interaction term coefficient= 3.70, 95% CI: 1.18 to 11.60, p=0.02). Among infants exposed to maternal fever, prematurity resulted in 8.44 (95% CI: 2.82 to 25.29) fold increased risk for birth asphyxia death, whereas among infants of mothers without intrapartum fever, prematurity was associated with a 2.28 (95% CI: 1.69 to 3.09) times higher risk for birth asphyxia mortality. The risk of asphyxia was 7.12 (95% CI: 4.25 to 11.90) fold higher in preterm infants exposed to maternal fever vs. full-term infants of afebrile mothers.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identify risk factors for birth asphyxia mortality in a large population-based cohort of births in a rural, low resource region with high rates of home birth and neonatal mortality. Inferences from this data may potentially be made to other high-mortality regions of the developing world where the majority of neonatal deaths occur.

Socioeconomic status, measured by a range of variables including parental education and ethnicity, was significantly associated with increased risk of birth asphyxia mortality. The associations remained after adjustment for pre-established intrapartum risk factors. These socioeconomic factors may increase asphyxia risk by influencing maternal nutritional status, care-seeking and access to health care services during the antenatal and intrapartum periods. Furthermore, ethnicity may influence maternal height which may in turn affect birth asphyxia risk.20 Maternal height was not measured in this study, however.

Young maternal age has been linked with increased rates of neonatal mortality;25, 26 however, maternal age is difficult to disassociate from parity in young adolescents. Recent studies have shown an increased risk of prematurity among young nulliparous adolescents,27, 28 suggesting that prematurity and low birth weight may mediate the effect of young maternal age on neonatal mortality25 (V Sharma, personal communication, 2007). In this analysis, the excess risk of birth asphyxia mortality among adolescent mothers was significantly attenuated after controlling for antepartum and intrapartum risk factors (including parity and prematurity).

Antepartum hemorrhage, maternal fever, pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, prolonged rupture of membranes and obstructed labor have been associated with increased risk of birth asphyxia in multiple hospital-based studies.29-33 In this study, among self reported clinical symptoms reflecting these disease processes, maternal fever (indicative of infection) and swelling of the face, hands and/or feet (indicative of pre-eclampsia), were significant predictors of birth asphyxia death after controlling for other factors. As opposed to prior studies,20, 21 we chose to adjust for the other intrapartum risk factors to obtain estimates of the independent association of each risk factor. The subsequent non-significance of the adjusted relative risk of convulsions, vaginal bleeding and prolonged rupture of membranes may be due to the low numbers of women with these symptoms, as well as the self-reported and non-specific nature of data elicited by household surveys, compared to hospital-based diagnoses which may be verified by clinical observation or laboratory testing.

In resource-limited and rural settings such as Sarlahi, where home birth is customary and cost and transportation may deter care-seeking during childbirth,34 it is plausible that only the more complicated childbirths seek higher level medical care. This is reflected in our study by the association of deliveries “on the way to clinic” and in hospital facilities with significantly increased risk of birth asphyxia mortality, even after controlling for other factors. These findings highlight the need to evaluate the training of local birth attendants and hospital facilities in the recognition and management of clinical birth asphyxia in this setting.

The strongest risk factors for birth asphyxia mortality in this study were the combined, synergistic effects of maternal fever, as a sign of serious infection, and prematurity. In a previous study in the same area, the risk of 6-month mortality was 86.4 times higher in infants with symptoms of birth asphyxia, prematurity, and neonatal sepsis as opposed to those with only sepsis (Odds ratio [OR] 3.3), asphyxia (OR 4.9) or prematurity (OR 3.5).35 In Gadchiroli,36 the case fatality for preterm infants with sepsis was 51.9% versus prematurity (11.1%) or sepsis (0%) alone, while the case fatality for asphyxiated premature infants was 66.7% versus birth asphyxia alone (25%). The synergy between birth asphyxia, infection and prematurity may be explained by a common inflammatory pathway of neonatal brain injury involving cytokines and chemokines, which stems from hypoxic-ischemic insult (IL-6, IL1β, ICAM, and IL-8),37-40 exposure to maternal intrauterine infection (IL-6),41 and prematurity (IL-6, TNF-α, PGE).42 Furthermore, premature infants are more vulnerable to cytokine-induced damage due to the immaturity of their blood-brain barrier. Taken altogether, our findings highlight the importance of integrated maternal-neonatal care, including community-based recognition and treatment of maternal infections during pregnancy to reduce not only prematurity, but also birth asphyxia mortality.

The lack of a standard community-based definition of birth asphyxia is a limitation to our study. To address this, we explored several verbal autopsy definitions of birth asphyxia and developed specific methods in order to most accurately identify birth asphyxia cases. These methods are described in detail elsewhere (unpublished data). However, given that almost all deaths occurred without medical supervision, our case definitions of birth asphyxia were not validated by physiologic measurements or physician examination. Other limitations include potential reporting bias of maternal and/or infant symptoms and recall bias in the verbal autopsy interviews. Recall periods ranging up to 12 months are considered acceptable,43 and in this study, 92% of interviews were conducted within 24 hours of the infant’s death, limiting recall bias.

Conclusions

The high rate of birth asphyxia mortality in Sarlahi, Nepal, emphasizes the urgent need to develop and evaluate strategies for the identification and management of birth asphyxia in home, community, and peripheral health facility settings. Standardized community-based definitions of birth asphyxia need to be developed.12 Furthermore, our data highlights the critical inter-relationship between maternal infections and prematurity as co-morbid risk factors for birth asphyxia mortality, thus calling for increased attention to the early recognition and management of these factors in community-based maternal and child health programs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was conducted by the Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, under grants from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland (HD 44004, HD 38753, R03 HD 49406), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, Washington (810-2054), and Cooperative Agreements between JHU and the Office of Health and Nutrition, US Agency for International Development, Washington DC (HRN-A-00-97-00015-00, GHS-A-00-03-000019-00). Commodity support was provided by Procter and Gamble Company, Cincinnati, Ohio.

The authors have no financial relationships or competing interests relevant to this article to disclose.

ROLE OF FUNDERS

Financial supporters and the commodity supplier played no role in the design, conduct, management, analysis, or interpretation of the results or in the preparation, review, or approval of this article.

Abbreviations

- RR

Relative Risk

- CI

Confidence Interval

- OR

Odds Ratio

- BA

Birth Asphyxia

- WHO

World Health Organization

- SD

Standard Deviation

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization . Basic Newborn Resuscitation: A Practical Guide. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1997. [Accessed February 27, 2007]. Available: http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/MSM_98_1/MSM_98_1_introduction.en.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis M, Manandhar DS, Manandhar N, Wyatt J, Bolam AJ, Costello AM. Stillbirths and neonatal encephalopathy in kathmandu, nepal: An estimate of the contribution of birth asphyxia to perinatal mortality in a low-income urban population. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2000;14:39–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2000.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchmann EJ, Pattinson RC, Nyathikazi N. Intrapartum-related birth asphyxia in South Africa--Lessons from the first national perinatal care survey. S Afr Med J. 2002;92:897–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knippenberg R, Lawn JE, Darmstadt GL, et al. Systematic scaling up of neonatal care in countries. Lancet. 2005;365:1087–1098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baqui AH, Darmstadt GL, Williams EK, et al. Rates, timing and causes of neonatal deaths in rural India: Implications for neonatal health programmes. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:706–713. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.026443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule S, Deshmukh M, Reddy MH. Burden of morbidities and the unmet need for health care in rural neonates--a prospective observational study in Gadchiroli, India. Indian Pediatr. 2001;38:952–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005;365:891–900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawn J, Shibuya K, Stein C. No cry at birth: Global estimates of intrapartum stillbirths and intrapartum-related neonatal deaths. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:409–417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanton C, Lawn JE, Rahman H, Wilczynska-Ketende K, Hill K. Stillbirth rates: Delivering estimates in 190 countries. Lancet. 2006;367:1487–1494. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68586-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . World Health Report. WHO; Geneva: 2005. [Accessed 3/1/2007]. 2005;2005. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2004/annex/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Committee on Fetus and Newborn. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Obstetric Practice. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Use and abuse of the Apgar score. Pediatrics. 1996;98:141–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawn JE, Manandar A, Haws R, Darmstadt GL. Reducing one million child deaths from birth asphyxia -- policy and programme gaps and priorities based on an international survey. Health Res Policy Systems. 2007;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-5-4. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule SB, Reddy HM, Deshmukh MD. Management of birth asphyxia in home deliveries in rural Gadchiroli: The effect of two types of birth attendants and of resuscitating with mouth-to-mouth, tube-mask or bag-mask. J Perinatol. 2005;25(Suppl 1):S82–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullany LC, Darmstadt GL, Khatry SK, et al. Topical applications of chlorhexidine to the umbilical cord for prevention of omphalitis and neonatal mortality in southern Nepal: A community-based, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;367:910–918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68381-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tielsch JM, Darmstadt GL, Mullany LC, et al. Impact of newborn skin-cleansing with chlorhexidine on neonatal mortality in southern Nepal: A community-based, cluster-randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e330–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anker M, Black RE, Coldham C, Kalter HD, Quigley MA, Ross D. A standard verbal autopsy method for investigating causes of death in infants and children. WHO/CDS/CSR/ISR/99. 1999;4:1–78. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freeman JV, Christian P, Khatry SK, et al. Evaluation of neonatal verbal autopsy using physician review versus algorithm-based cause-of-death assignment in rural Nepal. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2005;19:323–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baqui AH, Darmstadt GL, Williams EK, et al. Rates timing and causes of neonatal deaths in rural india: Implications for neonatal health programs. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2006;84:706–713. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.026443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawn JE, Wilczynska-Ketende K, Cousens SN. Estimating the causes of 4 million neonatal deaths in the year 2000. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:706–718. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellis M, Manandhar N, Manandhar DS, Costello AM. Risk factors for neonatal encephalopathy in Kathmandu, Nepal, a developing country: Unmatched case-control study. BMJ. 2000;320:1229–1236. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badawi N, Kurinczuk JJ, Keogh JM, et al. Intrapartum risk factors for newborn encephalopathy: The western Australian case-control study. BMJ. 1998;317:1554–1558. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7172.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh GK, Kogan MD. Persistent socioeconomic disparities in infant, neonatal, and postneonatal mortality rates in the United States, 1969-2001. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e928–39. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnot P. Prolonged labor. Calif Med. 1952;76:20–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berg AT, Bracken MB. Measuring gestational age: An uncertain proposition. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:280–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olausson PO, Cnattingius S, Haglund B. Teenage pregnancies and risk of late fetal death and infant mortality. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:116–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fraser AM, Brockert JE, Ward RH. Association of young maternal age with adverse reproductive outcomes. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1113–1117. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504273321701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart CP, Katz J, Khatry SK, et al. Preterm delivery but not intrauterine growth retardation is associated with young maternal age among primiparae in rural Nepal. Matern Child Nutr. 2007;3:174–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.da Silva AA, Simoes VM, Barbieri MA, et al. Young maternal age and preterm birth. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2003;17:332–339. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2003.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaye D. Antenatal and intrapartum risk factors for birth asphyxia among emergency obstetric referrals in Mulago hospital, Kampala, Uganda. East Afr Med J. 2003;80:140–143. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v80i3.8683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mbweza E. Risk factors for perinatal asphyxia at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Malawi. Clin Excell Nurse Pract. 2000;4:158–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daga AS, Daga SR, Patole SK. Risk assessment in birth asphyxia. J Trop Pediatr. 1990;36:34–39. doi: 10.1093/tropej/36.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandra S, Ramji S, Thirupuram S. Perinatal asphyxia: Multivariate analysis of risk factors in hospital births. Indian Pediatr. 1997;34:206–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall DR, Smith M, Smith J. Maternal factors contributing to asphyxia neonatorum. J Trop Pediatr. 1996;42:192–195. doi: 10.1093/tropej/42.4.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borghi J, Ensor T, Neupane BD, Tiwari S. Financial implications of skilled attendance at delivery in Nepal. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:228–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christian P, Darmstadt G, Wu L, et al. The impact of maternal micronutrient supplementation on early neonatal morbidity in rural nepal: A randomized, controlled community trial. Arch Dis Child. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.114009. manuscript in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bang AT, Reddy HM, Bang RA, Deshmukh MD. Why do neonates die in rural Gadchiroli, India? (part II): Estimating population attributable risks and contribution of multiple morbidities for identifying a strategy to prevent deaths. J Perinatol. 2005;25(Suppl 1):S35–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fotopoulos S, Mouchtouri A, Xanthou G, Lipsou N, Petrakou E, Xanthou M. Inflammatory chemokine expression in the peripheral blood of neonates with perinatal asphyxia and perinatal or nosocomial infections. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:800–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb01988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fotopoulos S, Pavlou K, Skouteli H, Papassotiriou I, Lipsou N, Xanthou M. Early markers of brain damage in premature low-birth-weight neonates who suffered from perinatal asphyxia and/or infection. Biol Neonate. 2001;79:213–218. doi: 10.1159/000047094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xanthou M, Fotopoulos S, Mouchtouri A, Lipsou N, Zika I, Sarafidou J. Inflammatory mediators in perinatal asphyxia and infection. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2002;91:92–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2002.tb02911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin-Ancel A, Garcia-Alix A, Pascual-Salcedo D, Cabanas F, Valcarce M, Quero J. Interleukin-6 in the cerebrospinal fluid after perinatal asphyxia is related to early and late neurological manifestations. Pediatrics. 1997;100:789–794. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stallmach T, Hebisch G, Joller-Jemelka HI, Orban P, Schwaller J, Engelmann M. Cytokine production and visualized effects in the feto-maternal unit. quantitative and topographic data on cytokines during intrauterine disease. Lab Invest. 1995;73:384–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hillier SL, Witkin SS, Krohn MA, Watts DH, Kiviat NB, Eschenbach DA. The relationship of amniotic fluid cytokines and preterm delivery, amniotic fluid infection, histologic chorioamnionitis, and chorioamnion infection. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:941–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soleman N, Chandramohan D, Shibuya K. Verbal autopsy: Current practices and challenges. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:239–245. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.027003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baskett TF, Allen VM, O’Connell CM, Allen AC. Predictors of respiratory depression at birth in the term infant. BJOG. 2006;113:769–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paul VK, Singh M, Sundaram KR, Deorari AK. Correlates of mortality among hospital-born neonates with birth asphyxia. Natl Med J India. 1997;10:54–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]