Abstract

We analyze the protein–RNA interfaces in 81 transient binary complexes taken from the Protein Data Bank. Those with tRNA or duplex RNA are larger than with single-stranded RNA, and comparable in size to protein–DNA interfaces. The protein side bears a strong positive electrostatic potential and resembles protein–DNA interfaces in its amino acid composition. On the RNA side, the phosphate contributes less, and the sugar much more, to the interaction than in protein–DNA complexes. On average, protein–RNA interfaces contain 20 hydrogen bonds, 7 that involve the phosphates, 5 the sugar 2′OH, and 6 the bases, and 32 water molecules. The average H-bond density per unit buried surface area is less with tRNA or single-stranded RNA than with duplex RNA. The atomic packing is also less compact in interfaces with tRNA. On the protein side, the main chain NH and Arg/Lys side chains account for nearly half of all H-bonds to RNA; the main chain CO and side chain acceptor groups, for a quarter. The 2′OH is a major player in protein–RNA recognition, and shape complementarity an important determinant, whereas electrostatics and direct base–protein interactions play a lesser part than in protein–DNA recognition.

INTRODUCTION

Protein–protein and protein–DNA recognition, illustrated by the many entries in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (1) that report X-ray or NMR structures of binary complexes, has been extensively analyzed and often reviewed (2–7). In comparison, structural data on protein–RNA recognition has been slow to come. The X-ray structures of the ribosome and of its subunits were a major advance, but the ribosome is only one of a number of biological assemblies that implicate both proteins and RNA, and in cells, the interaction of RNA and proteins takes many different forms. Albeit recent, the field of protein–RNA X-ray studies is very active, and the transverse analysis of the data deposited in the PDB, which was started at a time where few structures were available (8–12) and resumed recently on larger data sets (13–18), is still far from complete. In this paper, we select PDB entries that describe 81 non-redundant protein–RNA complexes, a majority of which were not considered in previous studies. We limit our selection to transient (non-obligate) binary systems, and leave out permanent multicomponent assemblies such as the ribosome and RNA viruses, which made up a large fraction of the previous datasets.

We analyze the protein–RNA interfaces in terms of size, composition, polar interactions and atomic packing, in the same way as we did for protein–protein and protein–DNA interfaces (3,4,19,20). This allows us to directly compare the three types of interfaces and draw conclusions on the mechanism of molecular recognition in each case. We find that, although the interfaces with DNA and RNA are similar in terms of size, number of hydrogen bonds, and amino acid composition, they are markedly different in several respects. The RNA phosphate contributes less and the sugar more than in DNA, and the sugar 2′OH plays a major role. Base recognition involves all the polar groups on the bases, but there is no recurrent pattern of interactions with protein groups, and no unique preference for interactions involving guanine as in DNA recognition. We find that the atomic packing is compact at the interfaces, and suggest that shape complementarity plays an important role in RNA recognition by proteins, along with the electrostatic interaction and the H-bonds to the 2′OH and bases. Thus, protein–RNA recognition has a number of features, electrostatic complementarity and base recognition among them, in common with protein–DNA recognition, but it also has shape complementarity in common with protein–protein recognition, and it displays a fully distinctive feature, the role of the 2′OH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The dataset of protein–RNA complexes

The PDB was scanned for entries representing protein–RNA interactions. About 266 entries reporting X-ray structures at resolution 3.0 Å or better and including both a polypeptide chain of 30 or more amino acid residues and a polyribonucleotide of 5 or more nucleotides were found. In order to remove redundancy, when the protein components in two entries had more than 35% identity, only the one with the better resolution was kept for further analysis. The final list of 81 complexes is reported in Table 1, references and further details on the complexes, in Supplementary Data.

Table 1.

The protein–RNA data set

| A. Complexes with tRNA (21) | |||||||||||

| 1asy | 1c0a | 1f7u* | 1ffy* | 1gax | 1h3e | 1h4s | 1j1u* | 1n78* | 1qf6 | 1qtq | 1ser |

| 1ttt | 1u0b* | 1vfg | 2azx | 2bte | 2csx | 2drb | 2fk6 | 2fmt | |||

| B. Ribosomal proteins (11) | |||||||||||

| 1dfu* | 1f7y | 1feu* | 1g1x | 1i6u | 1mji | 1mms | 1mzp | 1s03 | 1sds* | 2hw8* | |

| C. Duplex RNA (17) | |||||||||||

| 1di2* | 1e7k | 1hq1* | 1msw* | 1ooa | 1r3e* | 1rpu | 1si3 | 1wne | 1yvp* | 1zbi* | 2az0 |

| 2ez6* | 2f8s | 2gjw | 2hvy* | 2ipy | |||||||

| D. Single-stranded RNA (30) | |||||||||||

| 1a9n | 1av6 | 1cvj | 1g2e* | 1jbs* | 1jid* | 1k8w* | 1knz | 1kq2 | 1lng* | 1m5o* | 1m8v |

| 1m8w* | 1n35 | 1wpu* | 1wsu* | 1zbh | 1zh5* | 2a8v | 2anr* | 2asb* | 2b3j* | 2bx2 | 2db3* |

| 2f8k* | 2g4b | 2gic | 2i82* | 2ix1 | 2j0s* | ||||||

| E. Miscellaneous (2) | |||||||||||

| 2bgg* | 2bh2* |

Asterisk indicates PDB entry with resolution better than 2.4 Å.

Table 1 is split into four classes. Class A comprises complexes with tRNA, class B, with ribosomal proteins. Classes C and D differ by the RNA secondary structure. As the RNA in crystallized complexes often has both helical and single-stranded segments, the class was assigned on the basis of where the protein interacts: a stem-loop RNA belongs to class C if the interaction is mostly with the stem, to class D if it is with the loop. Ambiguous cases were checked with the Nucleic Acid Database (http://ndbserver.rutgers.edu/). Our assignment differed from theirs for 9 of 52 complexes, in which case we relied on the literature. The two entries that are reported in Table 1 as ‘miscellaneous’ could not be fitted in either class.

Interactions and crystal contacts

Crystallographic PDB entries report coordinates for the crystal asymmetric unit (ASU). Although the ASU has no biological significance, crystallographers tend to pick molecules forming biological units if they can. Therefore, we assumed that the relevant protein–RNA contacts occur within the ASU, except in cases where the protein or the RNA component has a crystal symmetry. In entry 1sds for instance, the protein molecules in the ASU interact with duplex RNA fragments, but the second strand is symmetry-derived. In 1sds and many other entries, the ASU contains several identical polypeptide chains. This may imply that the protein is oligomeric, most commonly a homodimer, or just reflect the crystal packing. A variety of situations are represented in our sample. In entry 1asy, the ASU contains subunits A and B of the yeast aspartyl-tRNA synthetase, and two tRNA molecules R and S; A is in contact only with R, B only with S. The enzyme is known to be a homodimer in solution, yet we kept only the A:R pair, as it fully describes the protein–RNA interaction. Tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (1h3e, 1j1u) and tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase (2azx) are also homodimers that bind two tRNA molecules, but here, both subunits interact with each tRNA, and the dimer was generated by symmetry like the RNA duplex in 1sds.

In crystals of protein–RNA or DNA complexes, the nucleic acid is almost always involved in crystal packing interactions (21). Because those may be confused with biologically relevant interactions, we checked all pairwise protein–RNA interfaces with the PISA server (22) (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/prot_int/pistart.html). In several cases, contacts made outside the ASU were at least as extensive as within. An example is the complex with RNase E (2bx2). The 5′-end of the ssRNA fragment enters the enzyme active site, but the remainder interacts with a symmetry-related protein (23). In entry 2f8s, the RNA has a 3′-overhang that interacts with the PAZ domain of one Argonaute protein molecule (24), and a helical body in contact with a second molecule in the ASU and molecules of adjacent ASU';s. In these two cases, the function determines which interactions are meaningful, but in others, the ambiguity may remain.

Interface area, hydrogen bonds, hydration

The size of the protein–RNA interfaces was estimated by measuring the area of the surface buried in the contact. We define the buried surface area (BSA) as the sum of the solvent accessible surface areas (ASA) of the two components less that of the complex. ASA values were measured with the program NACCESS (25), which implements the algorithm of Lee and Richards (26), a probe radius of 1.4 Å and default group radii. We count as part of the interface all the atoms, amino acid residues and nucleotides that lose ASA in the complex.

Hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) were identified with program HBPLUS (27) using default parameters. Interface water molecules were identified in 36 entries with resolution better than 2.4 Å (indicated by asterisks in Table 1). Following (28), all crystallographic solvent molecules located within 4.5 Å of interface atoms of both sides were considered as part of the interface.

RESULTS

The complexes and their RNA component

Table 1 distributes the 81 protein–RNA complexes into four classes (plus two ‘miscellaneous’) depending on the nature of the RNA. All are non-obligate, that is, the protein and RNA are not permanently associated, with the possible exception of the ribosomal proteins. Their RNA component comprises 42 nt on average, but the range is 5 (the cut-off value) to 97, and the four classes differ in their RNA size (Table 2). In class A, all but one of the tRNA';s have 74–94 nt. In class B, the fragments of rRNA in complex with ribosomal proteins have 30–60 nt. Classes C and D have shorter RNAs, and most of the small RNAs with <20 nt are in class D. In RNase H (1zbi) and T7 RNA polymerase (1msw), the RNA is in duplex with a DNA strand. In other complexes, all the segments longer than 15 nt fold into a hairpin or a higher order structure.

Table 2.

Average properties of the protein-RNA interfaces

| Average value of interface parameter | Protein/RNA | Protein/DNAa | Protein/proteinb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All classes | A tRNA | B ribosomal | C duplex RNA | D single-strand | |||

| Number of complexes | 81 | 21 | 11 | 17 | 30 | 75 | 70 |

| Nucleotides in RNA | 42 ± 28 | 76 | 47 | 33 | 21 | – | – |

| BSA (Å2) | 2530 ± 1210 | 3460 | 2260 | 2630 | 1890 | 3100 | 1910 |

| Protein | 1210 | 1660 | 1110 | 1270 | 880 | 1540 | – |

| Nucleic acid | 1320 | 1800 | 1150 | 1360 | 1010 | 1560 | – |

| Number of | |||||||

| Amino acids N_aa | 43 ± 21 | 61 | 34 | 45 | 33 | 48 | 57 |

| Nucleotides N_nu | 17.5 ± 10 | 26 | 21 | 18 | 10 | 18 | – |

| BSA (Å2) per | |||||||

| Amino acid | 28 | 27 | 33 | 28 | 27 | 33 | 33 |

| Nucleotide | 75 | 68 | 53 | 75 | 106 | 72 | – |

| Percentage buried atoms f_bu | |||||||

| Protein | 29 ± 9 | 24 | 31 | 41 | 32 | 24 | 34 |

| Nucleic acid | 29 ± 8 | 24 | 32 | 42 | 30 | 28 | – |

| Packing index L_Dc | |||||||

| Protein | 37 ± 8 | 35 | 37 | 36 | 38 | 39 | 42 |

| Nucleic acid | 43 ± 9 | 38 | 40 | 42 | 46 | 46 | – |

| H-bonds | |||||||

| Number per interface | 20 ± 11 | 25 | 19 | 24 | 15 | 22 | 10 |

| BSA per bond (Å2) | 125 | 141 | 117 | 110 | 126 | 145 | 190 |

| Water moleculesd | |||||||

| Number per interface | 32 ± 19 | 21 | 20 | ||||

| Per 1000 Å2 | 12.6 | 6.7 | 10.0 | ||||

| Bridging H-bonds | 11 ± 7 | 6 | |||||

aData from ref. (4).

bData from ref. (19).

cBahadur et al. (20) report values of L_D = 42 for protein-protein complexes and L_D = 32 for crystal packing interfaces. All other values are from this work.

dIn 36 PDB entries with resolution better than 2.4 Å. The data for protein-protein interfaces are from ref. (28).

Size of the protein–RNA interfaces

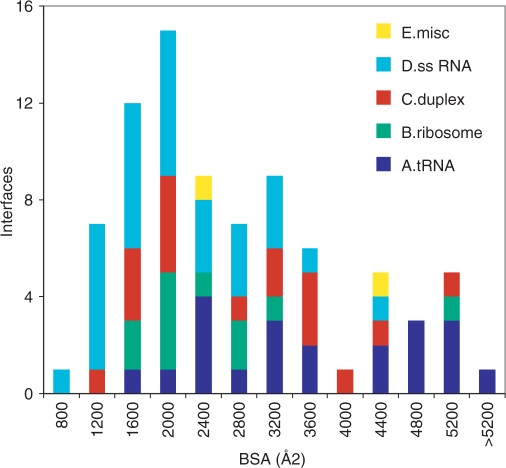

Table 2 lists average values of the protein and RNA surface area buried at the interface (BSA), the number of interface amino acid residues and nucleotides, and other properties discussed later. Table S1 (Supplementary Material) records individual values for each complex. The average interface in our sample buries 2530 Å2 that belong to 282 atoms, 43 amino acids and 17.5 nt. The average BSA is 36% larger in class A (tRNA) and 25% smaller in class D (ssRNA). The interfaces of class B (ribosomal proteins) are rather homogeneous in size, all but one being in the range 1200–2900 Å2; the exception (1glx) comprises three protein molecules, each of which contributes 1000–2000 Å2 to the BSA. In other classes, the histogram of Figure 1 shows a wide range of sizes, with a broad peak at BSA <2800 Å2 and another at BSA >4000 Å2. The first contains 60% of all the interfaces, and 80% of those of class D; the second, 20% of the interfaces, mostly of class A or C.

Figure 1.

Size of protein–RNA interfaces. Histogram of the buried surface area (protein plus RNA) in each of the 81 complexes. The classes are defined in Table 1.

Eight interfaces bury less than 1200 Å2; seven are of class D. The two smallest (1av6, 2a8v) involve short single-stranded segments in contact with one protein molecule through their end, and with a second molecule through their extended part. The second contact, treated here as a crystal packing interaction, may nevertheless be significant: in vivo, RNA appears to interact with two molecules of Rho (2a8v) (29). All other interfaces in our sample bury more than 900 Å2.

Interface atoms, residues and nucleotides

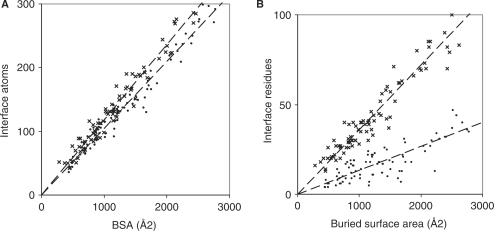

The BSA and the number of interface atoms in the 81 complexes are linearly correlated with a correlation coefficient R2 = 0.96 for both the protein and the RNA components (Figure 2A). Thus, the two are equivalent as a measure of the interface size. On average, an interface RNA atom contributes 9.5 Å2 to the BSA, a protein atom, 8.5 Å2. In protein–protein complexes (3), the BSA per interface atom is 9.2 Å2. Thus, a protein atom in contact with RNA loses about 10% less ASA than a RNA atom in contact with a protein, and 8% less than when it is in contact with another protein.

Figure 2.

Buried interface area, atoms, residues and nucleotides. The number of interface atoms (A) and of interface amino acid residues or nucleotides (B) is plotted against the ASA lost by either the protein (x) or the RNA (•) component of the 81 complexes.

The number Naa of interface residues also correlates linearly with the BSA (Figure 2B, R2 = 0.92). On average, an amino acid residue in contact with RNA loses 28 Å2 ASA in all classes of complexes, except class B where the average is 33 Å2 (Table 2). In protein–DNA complexes (4), residues in contact with double-stranded DNA lose 34 Å2, with single-stranded DNA, 27 Å2. Protein–RNA complexes are in between. Each RNA nucleotide in contact with the protein loses 75 Å2 ASA, a mean value that hides large variations. The correlation with the BSA is much less good for Nnuc (R2 = 0.67) than for Naa and we note that the BSA per nucleotide depends on the length of the RNA fragment. The average interface nucleotide loses 136 Å2 in fragments with 15 nt or less (21 complexes, mostly of class D), but only 66 Å2 when the RNA is 60 nt long or more (24 complexes, mostly tRNA in class A). This 2-fold difference can safely be attributed to the fact that the shorter fragments are single-stranded and tend to adopt an extended conformation, where the nucleotides are more available to the protein than in a RNA with secondary or tertiary structure. In protein–DNA complexes (4), the BSA per interface nucleotide is 130 Å2 with ssDNA, and 68 Å2 with dsDNA. The short ssRNA fragments of class D behave like ssDNA, the longer ones in other classes, like ds DNA, in terms of the surface area that is buried in contact with a protein.

Asymmetry of the protein and RNA contributions

Whereas the protein and the RNA contribute a similar number of atoms (about 140 on average) to the interface, the RNA contributes more to the BSA (Table 2). We estimate the excess RNA contribution in a complex as the ratio:

where B1 is the area lost by the RNA, B2 by the protein. The ratio, 5% on average, varies from ≈0 in class B to 7% in class D. It exceeds 20% in 1knz and 2a8v, two complexes of class D with very short RNAs; 1knz has only 5 nt, essentially buried inside the protein. All the complexes where r exceeds 10% have a RNA shorter than 15 nt. Nevertheless, the asymmetry also exists with long RNAs: the 24 complexes with a RNA of more than 60 nt have r = 4% on average. This can be attributed to the shape of the nucleic acid, which offers a convex surface to the protein no matter of whether it adopts an extended, a helical, or a loop conformation. When a molecule with a convex shape fits into a concave binding site, the latter tends to lose less ASA, because the ASA is measured one probe radius away from the molecular surface. This effect was observed first in protease-inhibitor complexes, where the inhibitor offers a convex surface that fits into a concave active site and the BSA is distributed 46:54 (r = 8%) between the protease and the inhibitor (3). In most other protein–protein complexes, the interface is flat and the BSA distributed 50:50.

Buried atoms and the atomic packing at the interface

An interface atom may be fully buried (ASA = 0 in the complex), or remain partially accessible to the solvent molecules. On average, the fraction of fully buried atoms on both the protein and the RNA side of the interfaces is f_bu = 29% (Table 2), but the range is 15% (1jbs, 1vfg) to 50% (1kq2, 1knz: two complexes of class D with very short RNA fragments). Class A resembles protein–DNA interfaces with a low average f_bu = 24%, whereas the other classes are more similar to protein–protein interfaces (f_bu = 34%) in that respect.

The f_bu fraction is related to the compactness of the atomic packing at the interface. Following (20), we calculate the packing index L_D as the mean number of interface atoms that are within 12 Å of another interface atom. Protein atoms in contact with RNA have L_D ≈37, a value intermediate between those observed for the interfaces of protein–protein complexes (L_D = 42) and for crystal packing contacts (L_D = 32). The atomic packing at the interfaces of protein–protein complexes has been shown to be as dense as the protein interior (3), whereas crystal contacts are poorly packed (20). The finding that protein–RNA (or DNA) interfaces bury relatively fewer atoms and have a lower packing index than protein–protein interfaces, suggests that they are not as tightly packed, but there are obvious differences between classes, and class A has low values of both f_bu and L_D.

Chemical composition of the interfaces

In Table 3, the average chemical composition of the solvent accessible surface and the interfaces is expressed as the contribution of different atom types to the ASA or BSA. On the protein side, the interfaces are largely composed of side-chain atoms. The main chain contributes 15% of the BSA, the side chains, 85%. The main chain contribution resembles protein–DNA interfaces, and is less than to the protein surface and to protein–protein interfaces.

Table 3.

Chemical composition of the interfaces

| Average area contribution (%)a | Protein–RNA | Protein–DNAb | Protein–proteinc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interface | Accessible surface | Interface | Accessible surface | Interface | Accessible surface | |

| Polypeptided | ||||||

| Main chain | 15 | 20 | 13 | 20 | 20 | 23 |

| Side chain | 85 | 80 | 87 | 80 | 80 | 77 |

| Non-polar | 55 | 56 | 52 | 56 | 58 | 55 |

| Neutral polar | 21 | 22 | 24 | 23 | 28 | 29 |

| Charged (positive) | 20 | 12 | 23 | 12 | 9 | 8 |

| Charged (negative) | 4 | 10 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 8 |

| Nucleotidee | ||||||

| Phosphate | 26 | 32 | 43 | 35 | ||

| Sugar | 39 | 36 | 29 | 38 | ||

| Base | 35 | 32 | 27 | 28 | ||

| Non-polar | 33 | 30 | 41 | 47 | ||

| Neutral polar | 41 | 39 | 16 | 19 | ||

| Charged (negative) | 26 | 32 | 43 | 34 | ||

aThe contributions of each atom type to the BSA or ASA are averaged over all the complexes.

bTaken from ref. (4).

cCalculated on the dataset in ref. (19).

dAll carbon-containing groups are counted as nonpolar; O, N and S are counted as polar; N is positively charged in Arg/Lys side chains. O negatively charged in Asp/Glu side chains.

eO1P, O2P and P atoms are ‘phosphate’. All carbon-containing groups are ‘non-polar’; N and O are ‘neutral polar’ except for O1P and O2P, which are negatively charged.

On average, non-polar (carbon-containing) groups contribute 55% of the BSA on the protein side, 33% on the RNA side. These fractions are nearly the same as for the solvent accessible surface. They are essentially independent of the class of the interface and its size, although the spread is greater in small interfaces that contain few atoms. In Table 3, we further divide the polar component as being positively charged in Arg and Lys side chains, negatively charged in Asp and Glu side chains, or neutral (N, O and S in the main chain and all other side chains). The neutral polar component distributes evenly between the interfaces and the accessible surface, but not the charged components: the protein surface in contact with RNA is enriched in positive charges and strongly depleted in negative charges. This is like protein–DNA interfaces, but not protein–protein interfaces, which resemble much more the protein accessible surface.

Figure 3 illustrates the shape and electrostatic potential of the protein surface in six protein–RNA complexes belonging to the different classes. In all panels, it has a noticeable concavity and is colored blue uniformly indicating a strong positive potential. The electrostatic potential alone is a strong indicator for a possible RNA-binding surface. In RNase E (2bx2), the blue color extends way outside the region in direct contact with the oligonucleotide, suggesting that the small interface (BSA = 910 Å2) seen in this crystal structure captures only part of the interaction with a natural RNA substrate. In the other panels, the RNA fills most of the concave blue protein surface, to which it is complementary in both shape and electric charge.

Figure 3.

Shape and electrostatic potential of protein–RNA interfaces. The molecular surface of the proteins is colored according to its electrostatic potential; blue is positive and red negative. The RNA backbone is drawn as a tube. (A) The RNase E subunit binds a 15-mer RNA with the 5′-end at its active site (23); the interface is one of the smallest in our sample, but the 15-mer makes other contacts in the crystal (2bx2, class D). (B) The splicing endonuclease is a dimer (36); it forms an average size interface with a double-stranded 19-mer (2gjw, class C). (C) Yeast arginyl-tRNA synthetase (37) forms an extensive interface with tRNA-Arg (1f7u, class A). (D) Ribosomal protein S8 in complex with a 37-mer stem-loop fragment of 16S rRNA (38) (1i6u, class B). (E) The SAM domain of the Vts1 post-transcriptional regulator in complex with a 16-mer hairpin RNA (39) (2f8k, class D). (F) The 15.5 kDa spliceosomal protein in complex with a 22-mer stem-loop fragment of U4 snRNA (40) (1e7k, class C). The figure was created using PyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA, http://www.delanoscientific.com).

The phosphates, which bear a negative charge, contribute 26% of the RNA BSA, significantly less than their contribution to the ASA or to protein–DNA interfaces (Table 3). In counterpart, the ribose contributes more (39%) than deoxyribose in protein–DNA complexes. The difference is largely due to the 2′OH, which contributes 15% of the RNA BSA on average, and up to 19% in class B (ribosomal proteins), but only 10% in class D (ssRNA). In both RNA and DNA, the bases contribute about equally to the ASA and the BSA. The non-polar component, made of the carbon-containing groups of the sugar and bases, represents about one-third of both the solvent accessible RNA surface and the surface in contact with proteins.

Amino acid and nucleotide composition

The average amino acid and nucleotide compositions of the solvent accessible surfaces and the interfaces are reported in Table 4. The compositions are either number-based (number fraction of the 20 amino acid types or 4 nucleotide types), or area-based (fraction of the ASA or BSA). For comparison, Table 4 also cites the area-based compositions of protein–DNA and protein–protein interfaces.

Table 4.

Amino acid and nucleotide compositions

| Composition | Number-Baseda | Area-Basedb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein–RNA | Protein–RNA | Protein–DNAc | Protein–proteind | |||||

| Surface | Interface | Surface | Interface | Surface | Interface | Surface | Interface | |

| Nucleotides | ||||||||

| A | 20.0 | 20.5 | 20.2 | 24.2 | 26.7 | 24.6 | ||

| U/T | 20.6 | 21.6 | 21.2 | 23.3 | 27.1 | 31.5 | ||

| G | 31.8 | 28.7 | 30.8 | 25.4 | 23.8 | 23.4 | ||

| C | 27.6 | 29.1 | 26.8 | 26.5 | 22.5 | 20.5 | ||

| Amino acids | ||||||||

| Ala | 5.6 | 4.8 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 2.6 |

| Arg | 8.4 | 13.6 | 12.6 | 20.6 | 12.1 | 23.8 | 8.9 | 10.1 |

| Asn | 4.2 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 5.5 |

| Asp | 6.9 | 5.3 | 7.1 | 3.8 | 6.4 | 1.6 | 7.1 | 5.2 |

| Cys | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.5 |

| Gln | 4.3 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 5.5 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 4.2 |

| Glu | 11.1 | 5.5 | 15.3 | 4.2 | 12.3 | 2.5 | 9.8 | 6.1 |

| Gly | 6.8 | 6.6 | 3.8 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 4.5 | 4.6 |

| His | 2.3 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 4.2 | 2.9 | 3.8 | 1.9 | 3.6 |

| Ile | 3.9 | 3.5 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 4.2 |

| Leu | 6.9 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 3.9 | 5.1 | 2.4 | 4.1 | 5.5 |

| Lys | 9.9 | 11.3 | 15.5 | 14.0 | 16.5 | 17.5 | 11.8 | 6.7 |

| Met | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 3.2 |

| Phe | 3.1 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 2.0 | 4.4 |

| Pro | 5.3 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 2.2 | 5.1 | 4.0 |

| Ser | 5.1 | 6.2 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 6.3 | 8.4 | 5.5 |

| Thr | 4.8 | 5.3 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 5.1 |

| Trp | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 4.5 |

| Tyr | 3.5 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 5.0 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 9.1 |

| Val | 4.7 | 4.0 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 3.8 |

The RNA segments in our sample contain more G and C than A or U/T. This is reflected in their respective contributions to the ASA, and also in the number-based composition of the interfaces. Yet, the BSA is split almost evenly between A, U/T, G and C. Thus, A and U/T contribute more to the BSA than to the ASA, whereas C contributes equally and G contributes less. On the protein side, the interface is depleted in acidic residues and enriched in Arg. The role of arginine in RNA-binding peptides and proteins has often been noted (9–16). Lys is also abundant, but not in excess relative to the protein surface. Arg/Lys contributes 28% of the protein ASA and 35% of the BSA; Asp/Glu, 22% of the ASA and 8% of the BSA. Arg/Lys contributes even more at protein–DNA interfaces, from which Asp/Glu are essentially excluded. The protein surface in contact with RNA is also enriched in aromatic residues, but not aliphatic residues: Phe, Tyr, Trp contribute 10% to the BSA versus 6% to the ASA; Ile, Leu, Met, Val contribute 11–12% to both.

Differences in composition may be expressed as an Euclidean distance Δf:

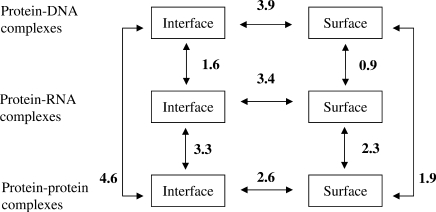

where fi and fi′ are the fraction of the area contributed by residue type i to two surfaces or interfaces (3). Figure 4 confirms that the protein surfaces in contact with RNA and DNA have a similar composition, that differs from both the solvent accessible surface and the interfaces of protein–protein complexes, but the difference is less with RNA than DNA.

Figure 4.

Euclidean distances between amino acid compositions. Values of Δf are calculated from the area based compositions in Table 4 as reported under ‘Results’ section.

Hydrogen bonds

The 81 complexes contain a total of 1637 H-bonds between protein and RNA groups. Thus, the average protein–RNA interface contains 20 H-bonds, but the range is wide: 2–58. The number of H-bonds tends to increase with the interface size, although the correlation with the BSA is mediocre (R2 = 0.61). Table 2 indicates that there is one bond on average per 125 Å2 BSA, and also that the H-bond density depends on the class. Class C has more, and class A less, H-bonds per unit BSA: tRNA makes large interfaces, but comparatively few H-bonds. Protein–DNA and protein–RNA interfaces have nearly the same average number of H-bonds, but the former are larger and their H-bond density is less, close to that of class A. Duplex RNA makes more H-bonds than DNA, largely thanks to the 2′OH. Protein–protein interfaces, which are less polar than protein–DNA or RNA interfaces, have a much lower H-bond density (Table 2).

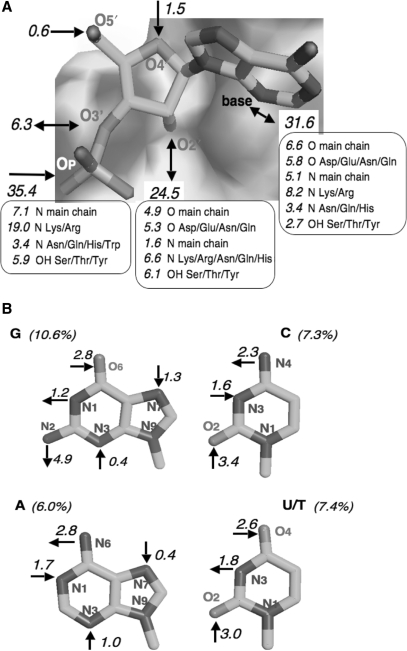

Table 5 and Figure 5 describe the chemical groups involved in protein–RNA H-bonds. On the protein side, the main chain NH and the Lys/Arg side chains account for nearly half. They donate bonds to the phosphates, and also the 2′OH and the bases. The most important H-bond acceptor is the main chain carbonyl, with either the 2′OH or the bases as donor. Other acceptor groups are the carboxylates of Asp/Glu (8% of the bonds) and side chain carbonyls of Asn/Gln (4%).

Table 5.

Protein–nucleic acid hydrogen bonds

| H bonds | Protein–RNA | Protein–DNAa |

|---|---|---|

| Number per interface | 20 | 22 |

| Protein chemical group (%)b | ||

| Main chain O | 12 | 10 |

| Main chain N | 14 | 18 |

| Side chain groups | 74 | 73 |

| N Arg, Lys | 34 | 41 |

| N Asn, Gln, His, Trp | 11 | 14 |

| OH Ser, Thr, Tyr | 17 | 17 |

| S Cys, Met | 0.2 | 1 |

| O Asp, Glu, Asn, Gln | 12 | – |

| Nucleic acid chemical group (%)b | ||

| Phosphate | 36 | 60 |

| Sugar | 33 | 6 |

| Base | 31 | 34 |

| Guanine | 10.5 | 16 |

| Adenine | 6.0 | 7 |

| Cytosine | 7.7 | 7 |

| Uracil/Thyminec | 7.4 | 4 |

aData from ref. (4).

bPercentage of the 1637 protein–RNA H bonds contributed by different chemical groups.

cIncludes pseudouracil.

Figure 5.

The H-bonding pattern of RNA to proteins. The numbers are percent fractions of the 1637 protein–RNA H-bonds identified in the 81 complexes; a 5% fraction represents approximately one bond per complex. (A) Bonds involving the RNA backbone. (B) Bonds involving the bases. U/T includes pseudouracil.

On the RNA side, the phosphate group is a major player, but less so than in DNA. On average, RNA phosphates make 36% of the H-bonds, or about 7 H-bonds per interface. DNA phosphates make almost twice as many, but with the same protein partners: the main chain NH';s and the Lys/Arg side chains, other side chains playing a lesser role (Figure 5A).

The main difference between protein–RNA and protein–DNA H-bonds is the role of the sugar. Whereas the deoxyribose of DNA plays essentially no part in H-bonding to proteins, ribose is heavily involved, and the 2′OH is the largest single contributor beyond the phosphate group. The 2′OH makes 25% of the H-bonds to proteins, that is, 5 H-bonds per interface on average, and it acts equally often as a donor to carboxylates and to main chain or side chain carbonyls, as an acceptor from main chain and side chain NH';s, or a donor/acceptor to/from a Ser/Thr/Tyr hydroxyl. The ribose 3′OH also appears in 6% of the H-bonds, essentially as a free 3′-terminal group. A free 3′OH is expected in the complexes with aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases or terminal transferases, but it may be an artifact in crystal structures with short oligonucleotides.

Base recognition

The bases account for 31% of the protein–RNA H-bonds, about 6 per interface. The polar groups on the bases are acceptors in 19%, donors in 12%. The N1 of purines and N3 of pyrimidines, which are inaccessible in a double helix, account for nearly 6% of the protein–RNA H-bonds, and the purine N3 and N7, which should be more free to interact, for only 3%. In complexes with double-stranded DNA, the N1 of purines and N3 of pyrimidines play no part, but the purine N3 and N7 account for 11% of the H-bonds (4). Major groove interactions with the O6/N6 and N7 atoms of purines, which account for 20% of the protein–DNA H-bonds (4), are much less common in protein–RNA complexes, and Figure 5B indicates no particular preference for the purine O6/N6 and N7 over the pyrimidine O2 and O4/N4 atoms.

G bases contribute more protein–RNA H-bonds than A, but they are also more abundant in our sample. The C and U/T bases contribute equally, although the former are more abundant. In protein–DNA complexes (4), G bases make twice as many H-bonds as A or C, and four times as many as T. In protein–RNA complexes, G and U/T become nearly equivalent after correcting for their relative abundance. An average interface with the base composition of Table 4 comprises five G bases that make an average of 0.46 H-bonds each, and four U/T that make 0.42; A or C bases make only 0.34 H-bonds. A protein–DNA interface typically comprises six G bases, each making an average of 0.6 H-bonds, mostly with Lys/Arg side chains located in the major groove. There are 2.5 Lys/Arg H-bonds to the O6 and N7 atoms of G in the average protein–DNA complex, but only 0.5 such bonds in the average protein–RNA complex of our set. With DNA, major groove recognition also involves Asn/Gln side chains H-bonding to N6 and N7 of A; this is very rare in our set.

Hydration

We identified interface water molecules in 36 entries with resolution better than 2.4 Å. Each interface contains 32 waters on average (Table 2), or about 13 per 1000 Å2 BSA; the range is 8–105. The 11 entries with resolution better than 2 Å contain the same average number of interface waters, but their surface density is higher: 18 per 1000 Å2 BSA. This confirms that protein–RNA interfaces are highly hydrated, and also that solvent is under-reported in medium resolution X-ray structures. Each interface water molecule makes 2.1 H-bond on average with polar groups on either the protein or the RNA. The phosphate is involved in 40% of the water–RNA H-bonds, the 2′OH in 29%, and the bases in 26%. On the protein side, water interacts most frequently with the main chain O (27%) and N (11%) atoms, with the Lys/Arg side chains (17%) and with Asp/Glu carboxylates (12%). A number of these interactions bridge the protein and RNA: 11 on average. Thus, the number of water-mediated protein–RNA H-bonds is more than half the number of direct H-bonds.

DISCUSSION

The present study aims to give a structural basis to the specific recognition between proteins and RNA, by applying to protein–RNA complexes the tools we developed for protein–protein and protein–DNA recognition (3,4,19,20). In preparing a set of PDB entries, we limited ourselves to binary complexes, and kept the ribosome and its subunits for a separate study. Our dataset is at least twice as large as in early studies (10–12), and it largely differs from those used in the more recent ones (14,15,18). Lejeune et al. (14) compared the atomic contacts between proteins and DNA or RNA; their dataset has 40 entries in common with ours, plus 9 that either are viral capsids or have less than 5 nt. Morozova et al. (15) center their study on base recognition; their dataset has 41 entries, 30 of which have an equivalent in our set. The work of Ellis et al. (18) is the most similar to ours. Their Table 1 lists 82 proteins; 50 are excluded from our set: 37 from ribosomal subunits, 3 from viral capsids, 8 NMR structures, 2 below our cutoff for resolution or RNA size. Only 31 entries are shared with our set, which makes the overlap less than 40%. Most belong to classes A and B, which correspond respectively to ‘tRNA’ and ‘rRNA’ in (18). The ‘mRNA’ and ‘ligand’ categories in (18) broadly cover our classes C and D, but these two classes contain a total of 47 entries, and only 5 have an equivalent in (18). The other 42 illustrates biological processes not represented in earlier studies.

We evaluate the size of the protein–RNA interfaces and express it as the area of the protein and RNA surfaces that are buried in contacts between the two molecules. The average BSA, about 2500 Å2, is less than in protein–DNA complexes (4) (3100 Å2), but consistent with the data of Jones et al. (11). Ellis et al. (18) quote a higher value (3220 Å2), presumably due to some very large interfaces in the ribosome (note that their Table 3 reports the equivalent of BSA/2). The average protein–RNA interface in our set implicates 17.5 nt and 43 amino acids, each nucleotide contributing 75 Å2 and each amino acid 28 Å2 to the BSA. In addition, we observe that, except perhaps in class B, the BSA distributes unequally between the RNA and the protein. We attribute this asymmetry to the convex shape of the nucleic acid fitting into a concave protein surface, and note that it is highest when the RNA is single stranded.

Many of the protein–RNA interfaces in our sample are similar in size to the subunit interfaces in homodimeric proteins (2,30), which have an average BSA of 3900 Å2. However, oligomeric proteins are permanent assemblies, whereas the protein–nucleic acid complexes that we selected are transient with few exceptions, and transient protein–protein complexes tend to have smaller interfaces (3): most are in the range 1200–2000 Å2. That range includes very few protein–DNA interfaces, and only one-third of the protein–RNA interfaces in our set, the great majority of which buries more than 2000 Å2. On the other hand, the smallest protein interfaces with double stranded DNA reported in (4) have a BSA near 1200 Å2, the smallest protein–protein interfaces, a BSA near 1100 Å2 in stable complexes (3) and 900 Å2 in short-lived electron transfer complexes (7). This suggests that an interface with a BSA of 900–1000 Å2 is required to form a stable, specific assembly between two biological macromolecules (6,7). As the number of interface nucleotides and residues scales linearly with the BSA, a protein–RNA interface with a BSA of 1000 Å2 implicates about 7 nt and 17 amino acids, close to what is observed in the smallest protein–DNA interfaces (4). Our set contains two interfaces that bury less than 900 Å2, and 10 that implicate fewer than 7 nt. All are in entries with a short RNA or where the RNA has other protein partners in the crystal packing. We therefore believe that the same minimum size rule applies to protein–RNA, protein–DNA and other types of macromolecular recognition in biology.

The buried protein and RNA surfaces comprise non-polar groups that form Van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions, and polar groups that form H-bonds. The non-polar groups contribute 55% of the BSA on the protein side, 33% on the RNA side, similar to the solvent accessible surface. The nature of the interacting groups and the contacts they make have been analyzed in details in (12,14–16) and need not be considered here. We do however report polar interactions. We find an average of 20 protein–RNA H-bonds per interface, somewhat less than the 25.5 H-bonds cited in Table 2 of Ellis et al. (18), but their sample contains large interfaces with many H-bonds, and the H-bond density per unit BSA is the same in the two studies. In addition, we note that the interfaces are highly hydrated, with an average of 32 water molecules per interface. This is much more than the 12 water molecules per interface reported earlier (12), but probably still an underestimate, since the high-resolution structures display a greater surface density: 18 waters per 1000 Å2 BSA. Protein–protein interfaces, with only 11 waters per 1000 Å2 in high-resolution structures (28), are less hydrated than protein–RNA interfaces, and also than protein–DNA interfaces (4,11,31).

All authors have noted that positively charged amino acid side chains play a major role in both RNA and DNA recognition. We find that Arg and Lys contribute about one-third of the BSA and a similar proportion of the polar interactions, and confirm the presence at the interfaces of aromatic residues (11–13,17). Asp and Glu, which bear negatively charges, are less completely excluded from the contact with RNA than DNA, and they accept H-bonds from the ribose and the bases. Other residue types contribute similarly to the protein accessible surface and the interfaces. The values in Table 4 may be converted into propensities that are not significantly different from those in (14,16,18), and similar to the propensities to be at an interface with DNA (4). Propensities are properties of the side chains, but the protein main chain also plays a part in RNA recognition. It contributes only 15% of the BSA, but makes 26% of the H-bonds. Allers and Shamoo (10) emphasize the role of the main chain in discriminating between the bases. We observe that it also interacts with the RNA backbone: the peptide NH donates H-bonds to the phosphates, the carbonyl accepts some from the sugar 2′OH.

On the RNA side, the phosphates contribute less to the buried surface and the polar interactions than they do in protein–DNA complexes, and the sugar contributes much more. This difference between DNA and RNA was noted by Lejeune et al. (14), who attributed it to differences in conformation. While conformation may play a part, we show here that the greater implication of the sugar is largely due to the 2′OH. This group, absent from DNA, makes major contributions to both the BSA and the polar interactions. Treger and Westhof (12) found the 2′OH to be involved in 21% of the H-bonds to proteins; the fraction is even larger, 25%, in our set. We observe that the 2′OH is both acceptor and donor, and has the main chain, side chains and interface waters as partners. The 2′OH, and the 3′OH in systems where the terminal group is free, are clearly essential players in protein–RNA recognition.

The polar interactions with the bases, which determine sequence specificity, have been at the center of a number of studies (12–15). However, not all the complexes in our set exhibit sequence specificity, and the base sequence can also be read indirectly. The accessibility of the bases is highly dependent on the conformation of the nucleic acid. Some of the RNAs in the complexes are in extended conformation, others form a standard double helix, but the large majority has an irregular structure that includes helical segments, loops and other elements. The capacity of the bases to pair with protein groups is very different in each case. As in previous studies (12,13), we observe that all the polar groups on the bases can H-bond to protein groups. This includes groups that are inaccessible in a double helix and do not participate in protein–DNA H-bonds. Base recognition in DNA is dominated by major groove interactions, it targets G more than other bases, and displays recurrent patterns of Lys/Arg bonding to G, Asn/Gln to A. We observe no such patterns in protein–RNA complexes, and find that G and U/T make more bonds to proteins than A and C, in agreement with (11) but at variance with (15) who report many more bonds involving G than U.

RNA displays a much wider variety of conformations and shapes than double-stranded DNA does, and it may be compared to proteins in that respect. The six complexes shown in Figure 3 offer a small sample of that variability, and the figure suggests that the protein surfaces recognize the molecular shape of the nucleic acid along with the charge distribution, which is rather uniform, and the nature of the bases. Thus, shape complementarity should be considered as a possible determinant of specificity. The complementarity between two molecular surfaces in contact allows their atoms to close-pack. When the quality of the atomic packing is evaluated by measuring Voronoi volumes, protein–protein interfaces are found to be as tightly packed as the protein interior (3); protein–DNA interfaces also, on the condition that interface solvent is taken into account (32). Another approach of the packing uses the gap volume index; Jones et al. (11) report values of this index that suggest that protein–RNA interfaces are packed less tightly than protein–DNA interfaces. We rely instead on the buried fraction f_bu and the L_D packing index. Their average values in Table 2 are higher for protein–RNA than for protein–DNA interfaces, which is at variance with (11). However, class A has f_bu and L_D values close to those of protein-DNA complexes, indicating that the interfaces with tRNA resemble those with DNA in their atomic packing as well as their size and H-bond density. The other classes have higher f_bu and L_D values, and their interfaces may be close-packed like protein–protein interfaces. The shape complementarity suggested by high f_bu and L_D values may result from an induced fit rather than pre-exist in the free protein and RNA. Conformation changes, frequent in protein–protein and protein–DNA complexes (2–6), are also well-established with tRNA (8,33–35). They may be the rule rather than the exception in protein–RNA recognition, but this can be assessed only if a structure is available for the free components as well as the complex. The recent analysis of twelve proteins for which this is the case, shows that eight undergo significant conformation changes, albeit not necessarily at the RNA binding site (41). This will have to be substantiated on a larger set of structures.

CONCLUSION

The cell machinery is made of macromolecular assemblies, all built out of proteins, and some of RNA as well. Most of the binary complexes that we analyze here are part of larger units, where their interfaces coexist with other protein–protein and protein–RNA interfaces. When we measure the size of the interfaces, their composition and the type of interactions they contain, our observations can certainly be extended to the larger assemblies, but it will be of great interest in future studies of the ribosome, the spliceosome and other molecular machines that contain both protein and RNA, to analyze the interplay between the different types of interfaces and their role in self-assembly.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

R.P.B. and M.Z. thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for financial support through grant Za153-11 to M.Z. J.J. acknowledges support of the 3D-Repertoire and SPINE2-Complexes programs of the European Union. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by IBBMC Université Paris-Sud.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berman HM, Battistuz T, Bhat TN, Bluhm WF, Bourne PE, Burkhardt K, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Acta Crystallog. Sect. 2002;D58:899–907. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902003451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones S, Thornton JM. Principles of protein-protein interactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:13–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lo Conte L, Chothia C, Janin J. The atomic structure of protein–protein recognition sites. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:2177–2198. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nadassy K, Wodak S, Janin J. Structural features of protein–nucleic acid recognition sites. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1999–2017. doi: 10.1021/bi982362d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones S, van Heyningen P, Berman HM, Thornton JM. Protein-DNA interactions: a structural analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;287:877–896. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wodak SJ, Janin J. The structural basis of macromolecular recognition. Adv. Prot. Chem. 2002;61:9–68. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(02)61001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janin J, Rodier F, Chakrabarti P, Bahadur R. Macromolecular recognition in the Protein Data Bank. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. 2007;D63:1–8. doi: 10.1107/S090744490603575X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cusack S. RNA–protein complexes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1999;9:66–73. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)80009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Draper D. Themes in RNA–protein recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;293:255–270. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allers J, Shamoo Y. Structure-based analysis of protein–RNA interactions using the program ENTANGLE. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;311:75–86. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones S, Daley D, Luscombe N, Berman H, Thornton J. Protein–RNA interactions: a structural analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:943–954. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.4.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Treger M, Westhof E. Statistical analysis of atomic contacts at RNA-protein interfaces. J. Mol. Recogn. 2001;14:199–214. doi: 10.1002/jmr.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeong E, Kim H, Lee S, Han K. Discovering the interaction propensities of amino acids and nucleotides from protein–RNA complexes. Mol. Cells. 2003;16:161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lejeune D, Delsaux N, Charloteaux B, Thomas A, Brasseur R. Protein-nucleic acid recognition: statistical analysis of atomic interactions and influence of DNA structure. Proteins. 2005;61:258–271. doi: 10.1002/prot.20607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morozova N, Allers J, Myers J, Shamoo Y. Protein-RNA interactions: exploring binding patterns with a three-dimensional superposition analysis of high resolution structures. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2746–2752. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim OT, Yura K, Go N. Amino acid residue doublet propensity in the protein-RNA interface and the application to RNA interface prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6450–6460. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker CM, Grant GH. Role of aromatic amino acids in protein-nucleic acid recognition. Biopolymers. 2007;85:456–470. doi: 10.1002/bip.20682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellis JJ, Broom M, Jones S. Protein–RNA interactions: structural analysis and functional classes. Proteins. 2007;66:903–911. doi: 10.1002/prot.21211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakrabarti P, Janin J. Dissecting protein-protein recognition sites. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 2002;47:334–343. doi: 10.1002/prot.10085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bahadur RP, Chakrabarti P, Rodier F, Janin J. A dissection of specific and non-specific protein–protein interfaces. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;36:943–955. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phipps KR, Li H. Protein–RNA contacts at crystal packing surfaces. Proteins. 2007;67:121–127. doi: 10.1002/prot.21230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callaghan AJ, Marcaida MJ, Stead JA, Mcdowall KJ, Scott WG, Luisi BF. Structure of E. Coli Rnase E catalytic domain and implications for RNA processing and turnover. Nature. 2005;437:1187–1191. doi: 10.1038/nature04084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan YR, Pei Y, Chen HY, Tuschl T, Patel DJ. A potential protein-RNA recognition event along the RISC-loading pathway from the structure of A. aeolicus argonaute with externally bound siRNA. Structure. 2006;14:1557–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hubbard SJ. NACCESS: program for calculating accessibilities. University College of London: Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee B, Richards FM. The interpretation of protein structures: estimation of static accessibility. J. Mol. Biol. 1971;55:379–400. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDonald I, Thornton JM. Satisfying hydrogen-bonding potential in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;238:777–793. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodier F, Bahadur RP, Chakrabarti P, Janin J. Hydration of protein-protein interfaces. Proteins. 2005;60:36–45. doi: 10.1002/prot.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bogden CE, Fass D, Bergman N, Nichols MD, Berger JM. The structural basis for terminator recognition by the Rho transcription termination factor. Mol. Cell. 1999;3:487–493. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80476-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bahadur RP, Chakrabarti P, Rodier F, Janin J. Dissecting subunit interfaces in homodimeric proteins. Proteins. 2003;53:708–719. doi: 10.1002/prot.10461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janin J. Wet and dry interfaces: the role of solvent in protein-protein and protein-DNA recognition. Structure. 1999;7:R277–R279. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)88333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nadassy K, Tomas-Oliveira I, Alberts I, Janin J, Wodak SJ. Standard atomic volumes in double-stranded DNA and packing in protein-DNA interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3362–3376. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.16.3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giegé R, Sissler M, Florentz C. Universal rules and idiosyncratic features in tRNA identity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;6:5017–5035. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.22.5017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodnina MV, Gromadski KB, Kothe U, Wieden HJ. Recognition and selection of tRNA in translation. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:938–942. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perona JJ, Hou YM. Indirect readout of tRNA for aminoacylation. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10419–10432. doi: 10.1021/bi7014647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xue S, Calvin K, Li H. RNA recognition and cleavage by an splicing endonuclease. Science. 2006;312:902–910. doi: 10.1126/science.1126629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delagoutte B, Moras D, Cavarelli J. tRNA aminoacylation by arginyl-tRNA synthetase: induced conformations during substrates binding. EMBO J. 2000;19:5599–5610. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tishchenko S, Nikulin A, Fomenkova N, Nevskaya N, Nikonov O, Dumas P, Moine H, Ehresmann B, Ehresmann C, Piendl W, et al. Detailed analysis of RNA-protein interactions within the ribosomal protein S8-rRNA complex from the archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;311:311–324. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aviv T, Lin Z, Ben-Ari G, Smibert CA, Sicheri F. Sequence-specific recognition of RNA hairpins by the SAM domain of Vts1p. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:168–176. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vidovic I, Nottrott S, Hartmuth K, Luhrmann R, Ficner R. Crystal structure of the spliceosomal 15.5kD protein bound to a U4 snRNA fragment. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1331–1342. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00131-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ellis JE, Jones S. Evaluating conformational changes in protein structures binding RNA. Proteins. 2008;70:1518–1526. doi: 10.1002/prot.21647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.