Abstract

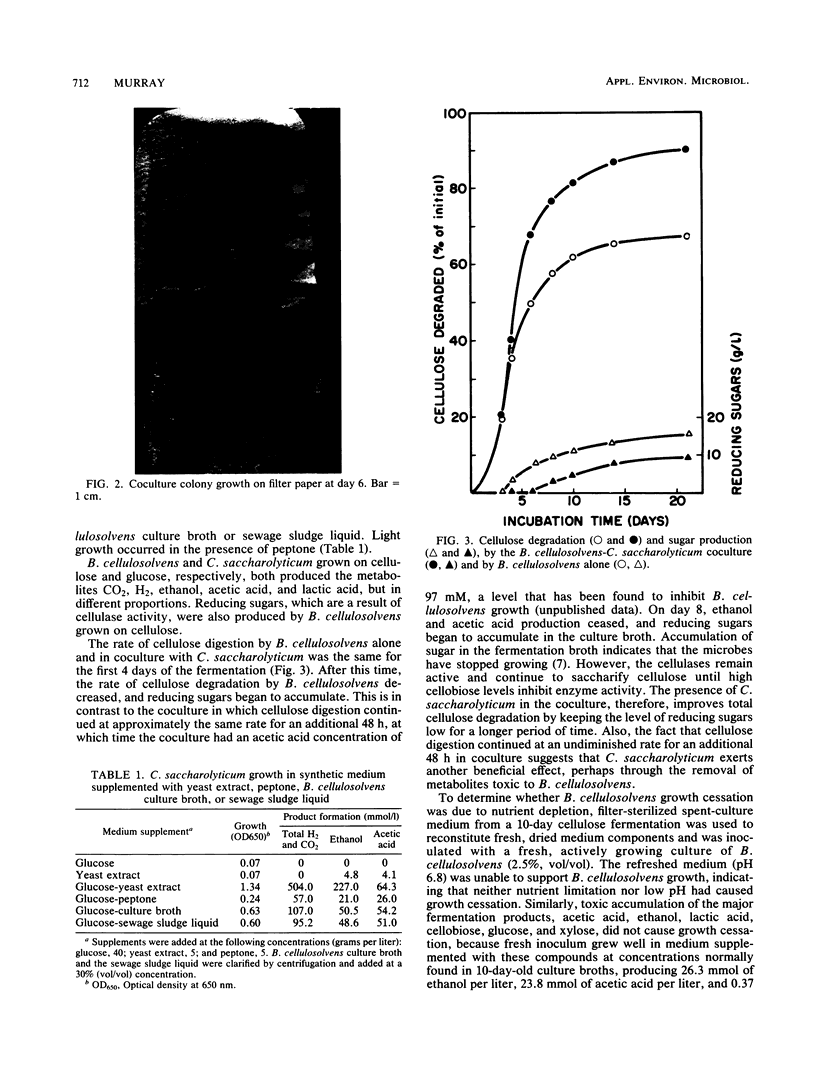

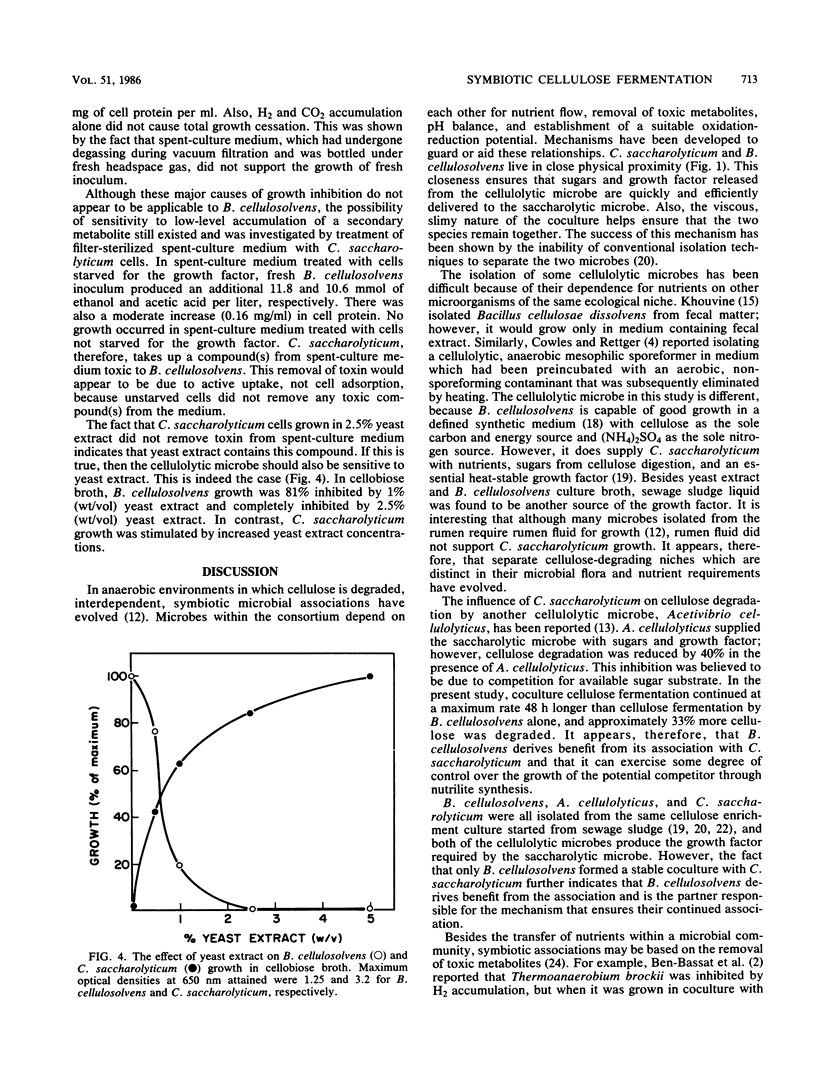

In coculture, Bacteroides cellulosolvens and Clostridium saccharolyticum fermented 33% more cellulose than did B. cellulosolvens alone. Also, cellulose digestion continued at a maximum rate 48 h longer in coculture. B. cellulosolvens hydrolyzes cellulose and supplies C. saccharolyticum with sugars and a growth factor replaceable by yeast extract. Alone, B. cellulosolvens exhibited an early cessation of growth which was not due to nutrient depletion, low pH, or toxic accumulation of acetic acid, ethanol, lactic acid, H2, CO2, cellobiose, glucose, or xylose. However, a 1-h incubation of B. cellulosolvens spent-culture medium with C. saacharolyticum cells starved for growth factor allowed a resumption of B. cellulosolvens growth. The symbiotic relationship of this naturally occurring coculture is one of mutualism, in which the cellulolytic microbe supplies the saccharolytic microbe with nutrients, and in turn the saccharolytic microbe removes a secondary metabolite toxic to the primary microbe.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ackman R. G. Porous polymer bead packings and formic acid vapor in the GLC of volatile free fatty acids. J Chromatogr Sci. 1972 Sep;10(9):560–565. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/10.9.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Bassat A., Lamed R., Zeikus J. G. Ethanol production by thermophilic bacteria: metabolic control of end product formation in Thermoanaerobium brockii. J Bacteriol. 1981 Apr;146(1):192–199. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.1.192-199.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell D. R., Bryant M. P. Medium without rumen fluid for nonselective enumeration and isolation of rumen bacteria. Appl Microbiol. 1966 Sep;14(5):794–801. doi: 10.1128/am.14.5.794-801.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles P. B., Rettger L. F. Isolation and Study of an Apparently Widespread Cellulose-Fermenting Anaerobe, Cl. cellulosolvens (N. Sp.?). J Bacteriol. 1931 Mar;21(3):167–182. doi: 10.1128/jb.21.3.167-182.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNGATE R. E. The anaerobic mesophilic cellulolytic bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1950 Mar;14(1):1–49. doi: 10.1128/br.14.1.1-49.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hungate R. E. Studies on Cellulose Fermentation: I. The Culture and Physiology of an Anaerobic Cellulose-digesting Bacterium. J Bacteriol. 1944 Nov;48(5):499–513. doi: 10.1128/jb.48.5.499-513.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLSON G. F. Optimal conditions for the enzymatic determination of L-lactic acid. Clin Chem. 1962 Feb;8:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styer D. J., Durbin R. D. Control of pH in liquid cultures of microorganisms with an ion-exchange resin. Can J Microbiol. 1982 Aug;28(8):986–988. doi: 10.1139/m82-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagg J. R., Dajani A. S., Wannamaker L. W. Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1976 Sep;40(3):722–756. doi: 10.1128/br.40.3.722-756.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]