Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) activates multiple signaling pathways. Two regions, C-terminal-activating region 1 (CTAR1) and CTAR2, have been identified within the cytoplasmic carboxy terminal domain that activates NF-κB. CTAR2 activates the canonical NF-κB pathway, which includes p50/p65 complexes. CTAR1 can activate both the canonical and noncanonical pathways to produce multiple distinct NF-κB dimers, including p52/p50, p52/p65, and p50/p50. CTAR1 also uniquely upregulates the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in epithelial cells. Increased p50-Bcl-3 complexes have been detected by chromatin precipitation on the NF-κB consensus motifs within the egfr promoter in CTAR1-expressing epithelial cells and nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. In this study, the mechanism responsible for the increase in Bcl-3 has been further investigated. The data indicate that LMP1-CTAR1 induces Bcl-3 mRNA and increases the nuclear translocation of both Bcl-3 and p50. LMP1-CTAR1 constitutively activates STAT3, and this activation was not due to the induction of interleukin 6 (IL-6). In LMP1-CTAR1-expressing cells, increased levels of activated STAT3 were detected by chromatin immunoprecipitation on STAT-binding sites located within both the promoter and the second intron of Bcl-3. A STAT3 inhibitor significantly reduced the activation of STAT3, as well as the CTAR1-mediated upregulation of Bcl-3 and EGFR. These data suggest that LMP1 activates distinct forms of NF-κB through multiple pathways. In addition to activating the canonical and noncanonical pathways, LMP1-CTAR1 constitutively activates STAT3 and increases Bcl-3. The increased nuclear Bcl-3 and p50 homodimer complexes positively regulate EGFR expression. These results indicate that LMP1 likely regulates distinct cellular genes by activating specific NF-κB pathways.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) is an essential factor in EBV-induced transformation and is expressed in many of the malignancies associated with EBV, including posttransplant lymphoma, Hodgkin's disease, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) (12, 28, 51, 66). LMP1 is considered a constitutively activated member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family and binds tumor necrosis factor-associated factors (TRAFs) (27, 41, 44). Two major signaling domains have been identified within the cytoplasmic C-terminal domains of LMP1, CTAR1, and CTAR2 that can activate NF-κB (25). However, CTAR1 has several unique properties and is essential for transformation, while CTAR2 is dispensable (34, 35). LMP1-CTAR1 uniquely induces expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) at the mRNA level, and this induction requires NF-κB and is mediated through the TRAF signaling pathway (41-43). Subsequent studies have identified other genes that are uniquely activated by LMP1-CTAR1, including TRAF1 and EBI3 (14).

The NF-κB transcription factors dimerize and bind NF-κB consensus sequences in cellular and viral promoters to regulate the expression of genes controlling inflammation, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, and oncogenesis (21, 38). There are five mammalian NF-κB family members, including p50, p52, p65 (RelA), c-Rel, and RelB. The activation of NF-κB family members is regulated through interactions with inhibitors of NF-κB (IκB), which sequester NF-κB members in the cytosol. Activation of a kinase cascade that includes IκB kinase alpha (IKKα), IKKβ, and IKKγ results in the phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and degradation of an IκB, leading to the release and nuclear translocation of NF-κB. The p50 and p52 precursor proteins, p105 and p100, respectively, can also function as IκB. Early studies initially showed that LMP1-CTAR1 activated multiple forms of NF-κB, including p50/p65, p50/p52, and p50 homodimers, and also greatly increased the processing of p100 to p52 in epithelial cells and the nuclear translocation of p50 (41, 48). It has subsequently been shown that the induction of processing of p100 represents another mechanism for the activation of NF-κB. This is considered the noncanonical NF-κB pathway, and the activation of this pathway is specific for LMP1-CTAR1 (1, 15, 33, 53). Noncanonical activation of NF-κB requires IKKα and is mediated through the NF-κB-inducing kinase NIK to induce the processing of p100 and to activate p52/relB. Canonical activation requires IKKβ and IKKγ to activate p50/p65. The activation of specific genes by LMP1 has been linked to the canonical and noncanonical pathways by use of engineered mouse fibroblasts (33). MIP-2 was activated by the canonical pathway, which is IKKβ/IKKγ dependent. Induction of the cellular chemokine CXCR4 required IKKα and was considered activated by the noncanonical pathway. An atypical pathway was also identified that was IKKβ dependent but independent of IKKγ and that regulated the expression of MIG and I-TAC.

The link between LMP1-CTAR1 activation of unique genes and distinct forms of NF-κB was demonstrated in studies that showed that LMP1-CTAR1 induced the binding of NF-κB p50 and Bcl-3 to the NF-κB sites in the egfr promoter in C33A cells (59). LMP1 effectively induces the nuclear translocation of p50, and p50/p50 homodimers are the major NF-κB complex activated in LMP1-expressing cells and EBV-positive xenografted NPC tumors (48, 58, 59). In addition, elevated levels of p50/p50 homodimers and Bcl-3 are found in classical Hodgkin's lymphoma and anaplastic large-cell lymphomas that are associated with EBV infection (37).

In this study, the effects of LMP1-CTAR1 on Bcl-3 expression and EGFR induction were further evaluated. LMP1-CTAR1 induced Bcl-3 transcription, resulting in increased levels of nuclear Bcl-3. The transcriptional activation of Bcl-3 required STAT3, which bound to sites within the Bcl-3 promoter and intron 2. LMP1-CTAR1 expression increased both the serine and tyrosine phosphorylations of STAT3 that are indicative of activation. These data indicate that LMP1 activates distinct forms of NF-κB through different pathways. In addition to activating the canonical and noncanonical pathways, LMP1-CTAR1 also activates p50/p50 homodimers by increasing the expression of Bcl-3 through its effects on STAT3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Retrovirus production and transduction.

Recombinant retrovirus production and transduction were performed as previously described to establish C33A stable cell lines expressing full-length LMP1, deletion mutant CTAR1(1-231) (contains only CTAR1 and not CTAR2), deletion mutant CTAR2(d187-351) (contains only CTAR2 and not CTAR1), or vector control pBabe (34). Briefly, ∼80% confluent 293T cells were triple transfected using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions with 5 μg pBabe (vector), pBabe-hemagglutinin (HA)-LMP1, pBabe-HA-1-231, or pBabe-HA-d187-351 and 5 μg pVSV-G- and 5 μg pGag/Pol-expressing plasmids. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, media were replaced with fresh media and cells were incubated at 33°C for another 24 h. Cell supernatant then was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min to remove cell debris and virus-containing supernatant was collected. C33A cells with ∼70 to 80% confluence were then transduced with clarified supernatant with 4 μg/ml Polybrene for 24 h at 37°C.

Cell culture and stable cell lines.

C33A cervical carcinoma cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma) and antibiotic/antimycotic (Gibco) at 37°C with 5% CO2. C33A stable cell lines expressing full-length LMP1, CTAR1(1-231), CTAR2(d187-351), or vector control pBabe were established by retroviral transduction followed by selection and passage in the presence of 1 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma).

Fractionation of cells.

After cultured cells reached ∼80 to 90% confluence, cells were scrape harvested, washed once with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco), centrifuged at 1,000 × g, and lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.1% deoxycholic acid) supplemented with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4), protease, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Lysates were then clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm, 4°C for 15 min, and supernatants containing whole-cell lysates were removed to new tubes. Nuclear extracts were made as previously described with slight modification (59). Briefly, cells were scrape harvested, washed once with cold PBS, and lysed by incubation in a hypotonic buffer (20 mM HEPES, 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA) supplemented with PMSF, Na3VO4, protease, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) for 15 min on ice. Nonidet P-40 was then added to a final concentration of 1%, followed by 1 min of vortexing. Nuclei were pelleted by low-speed centrifugation at 1,200 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected as a cytoplasmic fraction. The nuclear fractions were purified using the Optiprep reagent (Sigma) as directed by the manufacturer and as previously described (58). Nuclei were lysed with nuclear extraction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 25% glycerol, PMSF, Na3VO4, protease, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail Σ) with the salt concentration adjusted to 400 mM with 5 M NaCl. All lysates were stored at −80°C.

Western blot analysis.

Protein concentrations of cell lysates were determined using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay system according to the manufacturer's instructions. Equal amounts of protein were used for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to Optitran (Schleicher and Schuell) for Western blot analysis. Primary antibodies used include anti-p50, anti-β-actin, anti-GRP78, anti-STAT3, anti-poly (ADP- ribose) polymerase (anti-PARP) (Santa Cruz), anti-Bcl-3 (Upstate Biotechnology), anti-phospho-STAT3 (Ser 727 and Tyr 705) (Cell Signaling), anti-phospho-EGFR (Tyr 1068) (BD Biosciences), and anti-HA tag (Covance). A rabbit antiserum raised against the carboxyl-terminal 100 amino acids of the EGFR fused to glutathione S-transferase (kindly provided by H. Shelton Earp) was used to detect total EGFR. Secondary antibodies used to detect bound proteins include horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse, anti-rabbit (Amersham Pharmacia), and anti-goat (DAKO). Blots were developed using Pierce Supersignal West Pico chemiluminescence system followed by exposure to film.

ChIP analysis.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis was performed using a ChIP kit (Upstate Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cells were cultivated in 100-mm plates to 90% confluence and scrape harvested. Cells were then fixed for 5 min in 1% freshly made formaldehyde, washed with PBS, and lysed for 10 min in lysis buffer provided in the kit. Chromatin was sheared by sonication to an average size of ∼200 to 500 bp, clarified, and precleared for 1 h at 4°C with salmon sperm DNA-saturated protein G-Sepharose beads. The supernatant was incubated with normal rabbit immunoglobulin G, with anti-STAT3 (Santa Cruz), or with anti-phospho-STAT3 (Ser 727; Cell Signaling) and nutated overnight at 4°C. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with salmon sperm DNA-saturated protein G-Sepharose beads for 1 h at 4°C and washed extensively according to the manufacturer's instructions. Input and immunoprecipitated protein/DNA complexes were eluted at room temperature, and the cross-linking was reversed overnight at 65°C in the presence of 200 mM NaCl. After RNase A (37°C for 30 min) and proteinase K (45°C for 2 h) treatment, sample DNAs were purified as directed by the manufacturer for further analysis. PCR of ChIP products was performed with HotStar Taq polymerase (Qiagen), and primer pairs used for different ChIP target sequences include the following: for Bcl-3-Pro, 5′ TGACCCGGACTCAACCCCAG 3′ and 5′ TCTCCTCCCCTCCTCTCCCTC 3′; for HS3, 5′ CGCTTCCTCCAACCTTAACC 3′ and 5′ TGCCCAGTCCCTAACCTCTT 3′; and for HS4, 5′ CATTCGAGGATGGAAGTTGG 3′ and 5′ CAGGGTTAAGTGAGGGCAGA 3′.

QRT-PCR.

Total cell RNA was isolated using an RNeasy kit as directed by the manufacturer (Qiagen). Primer pairs used in this paper include the following: for actin, 5′ TCACCCACACTGTGCCCATCTACGA 3′ and 5′ CAGCGGAACCGCTCATTGCCAATGG 3′; for EGFR, 5′ CTGCGTCTCTTGCCGGAATG 3′ and 5′ TTGGCTCACCCTCCAGAAGG 3′; for Bcl-3, 5′ ACAACAGCCTTAGCATGGTG 3′ and 5′ GCTGAGTGCAGGGCGGAGCT 3′; and for interleukin 6 (IL-6), 5′ AGCCACTCACCTCTTCAGAAC 3′ and 5′ GCTGCTTTCACACATGTTACTCTT 3′. Quantitative real-time PCR (QRT-PCR) was performed using a Quantitect SYBR green reverse transcription-PCR kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Amplification of PCR products was detected using ABI 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed using SDS 2.0 software (Applied Biosystems). The cycle threshold (CT) was determined as the number of PCR cycles required for a given reaction to reach an arbitrary fluorescence value within the linear amplification range. The change in CT (ΔCT) was determined between the same target gene primer sets and different samples, and the change in ΔCT (ΔΔCT) was determined by adjusting for the difference in the number of cycles required for actin to reach the CT. The severalfold change was determined as 2ΔΔCT, since each PCR cycle results in a twofold amplification of each PCR product. QRT-PCR was also performed to amplify ChIP products and primer pairs used for different ChIP target sequences, including the following: for Bcl-3-Pro, 5′ TGACCCGGACTCAACCCCAG 3′ and 5′ TCTCCTCCCCTCCTCTCCCTC 3′; for HS3, 5′ CGCTTCCTCCAACCTTAACC 3′ and 5′ AAGAGGAGCCGGTGGCGCAG 3′; and for HS4, 5′ TTACTGGAAGTCCGAGGGCT 3′ and 5′ TTCAGAGAAACCGTCCAGGC 3′.

RESULTS

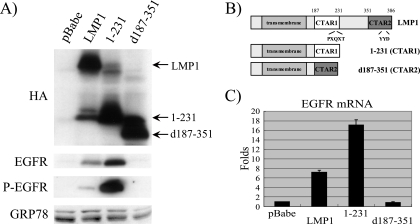

CTAR1 of LMP1 induces EGFR mRNA and protein.

The CTAR1 domain of LMP1 has previously been shown to induce the expression of the EGFR. The full-length LMP1 and the 1-231 (contains only CTAR1 and not CTAR2), and d187-351 (contains only CTAR2 and not CTAR1) constructs previously cloned into the pBabe retroviral expression vector were stably transduced into C33A epithelial cells (Fig. 1B) (17). Expression of LMP1 and the CTAR deletion mutants and EGFR expression were evaluated by immunoblotting (Fig. 1A). As previously shown, LMP1 and CTAR1 but not CTAR2 of LMP1 induced EGFR expression, with highly elevated levels induced by CTAR1 (43). In addition, high levels of phosphorylated, activated EGFR were detected using a phosphospecific antibody, indicating that the EGFR induced by CTAR1 is functionally active. QRT-PCR confirmed previous studies that indicated that LMP1 upregulates EGFR at the mRNA level (42) (Fig. 1C). Quantification of the immunoblot indicated that in C33A cells, LMP1 and CTAR1 induced EGFR mRNA expression 7-fold and 17-fold, respectively. LMP1-CTAR2 did not affect the EGFR mRNA level or the levels of phosphorylated EGFR protein. Although the levels of LMP1 expression were very similar, the total and activated EGFR levels induced by LMP1-CTAR1 were significantly higher than those induced by full-length LMP1. This suggests that CTAR2 or sequences between CTAR1 and CTAR2 may inhibit the ability of CTAR1 to induce specific targets, such as EGFR.

FIG. 1.

CTAR1 of LMP1 upregulates EGFR mRNA levels. (A) LMP1 and EGFR expression was examined by Western blot analysis for C33A cells expressing HA-tagged LMP1, deletion mutant 1-231, and deletion mutant d187-351. (B) A schematic of LMP1, 1-231, and d187-351 constructs. (C) Expression of EGFR mRNA in stable C33A cells was analyzed by QRT-PCR. Severalfold change was normalized to the value for actin. Data shown are the mean values of three independent experiments, each being performed in triplicate.

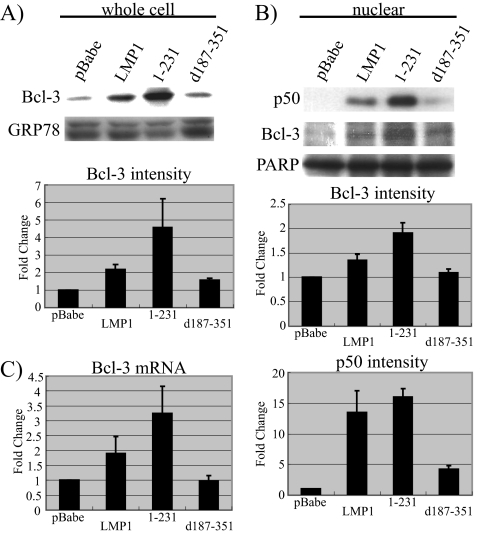

LMP1-CTAR1 upregulates Bcl-3 expression and induces nuclear translocation of Bcl-3 and p50.

In studies of EBV-positive NPC xenografts, p50 and Bcl-3 were detected by ChIP to be bound to the EGFR promoter, while other forms of NF-κB were not detected (58). In addition, in C33A cells, transient overexpression of Bcl-3 and/or p50 slightly increased EGFR expression and p50/Bcl-3 complexes could be detected by ChIP on the EGFR promoter in C33A cells expressing LMP1-CTAR1 (59). To determine the effect of LMP1 and LMP1-CTAR1 on the localization and expression levels of Bcl-3 and p50, lysates of whole-cell and nuclear fractions were analyzed by Western blotting. Both LMP1 and LMP1-CTAR1 increased levels of Bcl-3 in the whole-cell lysates; increases were approximately 2.1-fold and 4.6-fold, respectively (Fig. 2A). Elevated levels of p50 and Bcl-3 were also detected in the nuclei of the LMP1-expressing C33A cells (Fig. 2B). Equal loading was confirmed by immunoblotting for the cytosolic and nuclear proteins GRP78 and PARP. Quantification using the ImageJ software and normalization to the intensity of PARP bands indicated that LMP1-expressing C33A cells had a 1.4-fold increase in nuclear Bcl-3 and that LMP1-CTAR1-expressing cells had an approximately 1.9-fold increase. LMP1-CTAR2 did not affect the levels of whole-cell or nuclear Bcl-3 compared to vector control cells. Expression of LMP1 and LMP1-CTAR1 also significantly induced the nuclear translocation of NF-κB p50 by approximately 13- and 16-fold, respectively (Fig. 2B) (48). Although LMP1-CTAR2 induces higher levels of NF-κB activity in reporter assays, in C33A cells expressing LMP1-CTAR2, nuclear p50 was increased only fivefold (25, 57). QRT-PCR using Bcl-3-specific primers indicated that Bcl-3 mRNA was increased by inductions of approximately 1.9-fold and 3.3-fold in LMP1- and LMP1-CTAR1-expressing cells (Fig. 2C). LMP1-CTAR2 did not affect the Bcl-3 mRNA level. These results indicate that LMP1-CTAR1 not only induces the nuclear translocation of NF-κB Bcl-3 and p50 but also transcriptionally activates Bcl-3.

FIG. 2.

CTAR1 of LMP1 upregulates Bcl-3 and induces nuclear translocation of Bcl-3 and p50. (A) Bcl-3 expression in stable C33A cells was examined by Western blotting and quantitated using ImageJ software. Data shown are the mean values of three independent experiments. (B) Nuclear p50 and Bcl-3 in C33A stable cells were shown by Western blotting and quantitated using ImageJ software. Data shown are the mean values of four and three independent experiments for Bcl-3 and p50, respectively. Severalfold change was normalized to GRP78 and PARP values in panels A and B, respectively. (C) mRNA of Bcl-3 was examined by QRT-PCR. Severalfold change was normalized to the value for actin. Data shown are the mean values of three independent experiments, each being performed in triplicate.

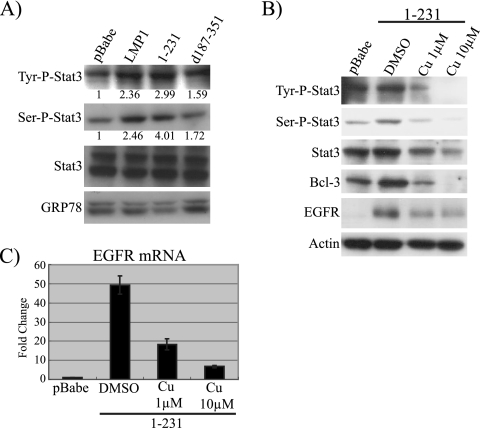

STAT3 is constitutively activated by LMP1-CTAR1.

Previous studies have shown that LMP1 can activate signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and that the activated STAT3 may regulate LMP1 expression through effects on the novel LMP1 promoter within the terminal repeats that is active in NPC (9, 10, 32, 52). STAT3 has also been shown to transcriptionally activate Bcl-3 through enhancer sequences detected within the Bcl-3 introns (4). The transcriptional activity of STAT3 is regulated by phosphorylation. Phosphorylation at tyrosine 705 induces Bcl-3 dimerization, while phosphorylation at serine 727 affects DNA binding and transcriptional activity (3, 13). To determine the effects of LMP1 and CTAR1 on STAT3 activation, serine- and tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT3 was identified using phosphospecific STAT3 antibodies, quantified by ImageJ, and normalized to the loading control, GRP78 (Fig. 3A). The severalfold induction is indicated beneath the corresponding bands of one representative experiment out of three independent attempts. Cells expressing LMP1 had an approximately 2.4-fold increase in tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT3 and a 2.5-fold increase in serine-phosphorylated STAT3 compared to what was seen for the vector control. Cells expressing LMP1-CTAR1 had an approximately threefold increase in tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT3 and a fourfold increase in serine-phosphorylated STAT3. LMP1-CTAR2 had an approximately 1.6-fold increase in tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT3 and a 1.7-fold increase in serine-phosphorylated STAT3. Although the levels of phosphorylated STAT3 were increased by LMP1, the total level of STAT3 was not affected.

FIG. 3.

CTAR1 of LMP1 upregulates Bcl-3 and EGFR by activating STAT3. (A) Total and phosphorylation levels of STAT3 were examined by Western blotting. Severalfold inductions are listed beneath their corresponding bands. The blot is representative of three independent experiments. (B) The phosphorylation of STAT3, as well as the expression of Bcl-3 and EGFR, was examined for 1-231-expressing C33A cells treated with the STAT3-specific inhibitor cucurbitacin. (C) mRNA of EGFR was examined by QRT-PCR in the pBabe control, 1-231 cells treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and 1-231 cells treated with cucurbitacin. Severalfold change was normalized to the value for actin. Data shown are the mean values of four independent experiments, each being performed in triplicate.

Cucurbitacin is a specific inhibitor of STAT3 activation through effects on the Janus kinases (JAKs) (2, 31). Treatment of the LMP1-CTAR1-expressing C33A cells with cucurbitacin reduced both the tyrosine and serine phosphorylation of STAT3 induced by LMP1-CTAR1 (Fig. 3B). The effects of cucurbitacin were dose dependent in that 1 μM of cucurbitacin reduced LMP1-CTAR1-mediated induction to the level detected in control cells, while 10 μM eliminated phosphorylated STAT3. Importantly, treatment with cucurbitacin significantly reduced the effects of LMP1-CTAR1 on Bcl-3 and EGFR, and at 10 μM expression of Bcl-3 was eliminated. QRT-PCR of EGFR mRNA indicated that EGFR mRNA was reduced 63% and 86% by 1 μM and 10 μM of cucurbitacin (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that CTAR1-mediated STAT3 activation is required for Bcl-3 induction and at least partially responsible for the induction of EGFR.

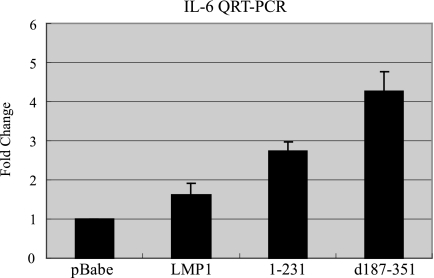

Previous studies have shown that LMP1 can induce the expression of IL-6, resulting in the activation of STAT3 (4, 9, 10, 16). To determine whether LMP1-mediated STAT3 activation resulted from IL-6 induction in C33A cells, QRT-PCR was performed to detect IL-6 mRNA (Fig. 4). In C33A cells, IL-6 mRNA levels were induced by LMP1, LMP1-CTAR1, and LMP1-CTAR2 to 1.6-, 2.7-, and 4.2-fold, respectively. The highest induction was detected in LMP1-CTAR2 cells that did not activate STAT3. These data indicate that STAT3 is constitutively activated by LMP1-CTAR1 in C33A cells through mechanisms that are not dependent on IL-6 induction.

FIG. 4.

LMP1 effects on IL-6. The expression level of IL-6 mRNA in stable C33A cells was analyzed by QRT-PCR. Severalfold change was normalized to the value for actin. Data shown are the mean values of four independent experiments, each being performed in triplicate.

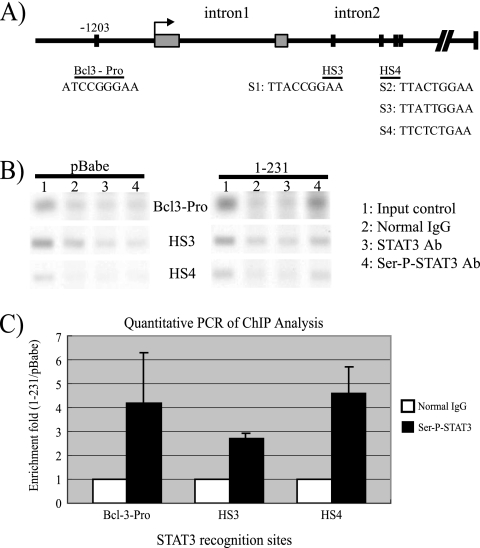

LMP1-CTAR1 induces STAT3 binding to sites in the Bcl-3 promoter and introns.

Two enhancers that mediate STAT3 induction of Bcl-3, HS3 and HS4, have been identified within introns of Bcl-3 (4). HS3 contains one and HS4 has three putative STAT3 binding sites, respectively (Fig. 5A). The online program ALGGEN-PROMO, which can be accessed online at http://www.lsi.upc.es/∼alggen under the research link, was also used to predict STAT3 binding sites in the Bcl-3 promoter. One potential site (Bcl-3-Pro) was identified at approximately 1,200 bp upstream of the Bcl-3 transcriptional start site (Fig. 5A) (18, 39). To determine if LMP1-CTAR1 induces binding of STAT3 to these putative binding sites, ChIP analysis was performed with C33A cells stably expressing the pBabe vector control and LMP1-CTAR1 using primers specific for each of the three predicted sites (Fig. 5B). In the pBabe control cells, precipitation with STAT3 or serine-phosphorylated STAT3 antibodies did not increase the amplification compared to what was seen for precipitation with normal rabbit immunoglobulin. For LMP1-CTAR1 cells, precipitation with STAT3 antibody slightly increased the amplification of all three putative STAT3 binding sites. However, precipitation with the serine-phosphorylated specific STAT3 antibody detected increased binding between STAT3 and all three putative STAT3 binding sites in the presence of LMP1-CTAR1. LMP1-CTAR1 did not increase interaction between STAT3 and a nonspecific target within EGFR Exon2, indicating the specificity of the effect (data not shown). This result was confirmed using quantitative PCR to amplify ChIP products, and the data were normalized to determine the severalfold level of enrichment in LMP1-CTAR1 cells compared to the pBabe control cell level (Fig. 5C). In LMP1-CTAR1 cells, the binding of serine-phosphorylated STAT3 to Bcl-3-Pro, H3, and H4 was increased 4.2-, 3-, and 4.6-fold, respectively. These data indicate that LMP1-CTAR1 likely regulates Bcl-3 by increasing the interaction of serine-phosphorylated STAT3 to multiple binding sites that regulate Bcl-3 expression.

FIG. 5.

LMP1-CTAR1 induces binding of STAT3 to Bcl-3 promoter and intronic enhancers. (A) Schematic representation of putative STAT binding sites. HS3 and HS4 were described in reference 4. Bcl-3-Pro was predicted using the ALGGEN-PROMO online program. (B) ChIP analysis using normal immunoglobulin G (IgG) (lane 2), STAT3 (lane 3), and serine-phosphorylated STAT3 (lane 4) antibodies (Ab) in pBabe control- and CTAR1-expressing C33A cells. Precipitated complexes were subjected to PCR with primer pairs specific to Bcl-3-Pro, HS3, and HS4 regions. PCR was also performed with chromatin input (lane 1). (C) QRT-PCR was performed to amplify ChIP products from pBabe control- and CTAR1-expressing cells. Severalfold enrichment was calculated by normalizing results from CTAR1 cells to those from pBabe cells. Data shown are the mean values of two independent experiments, each being performed in triplicate.

DISCUSSION

The induction of EGFR expression by LMP1 is likely a contributing factor in the development of cancer. The EGFR is frequently expressed at high levels in a variety of human cancers, including NPC (40, 54, 69). Stimulation of the tyrosine kinase activity of EGFR affects multiple signaling pathways, leading to the deregulation of cellular growth control and tumorigenesis (5, 65). Thus, the effect of LMP1 on EGFR expression is likely an important factor in carcinogenesis. The unique activation of EGFR expression by LMP1-CTAR1 provides a novel system to assess the contribution of NF-κB activation.

It was initially thought that p50/p50 or p52/p52 homodimers were transcriptionally inactive, as these forms of NF-κB lack transactivation domains. However, subsequent studies determined that Bcl-3, which contains a transcriptional transactivation domain, can convert these complexes into active forms (19, 46, 47). It is thought that one of the major functions of Bcl-3 is to bring p50 into the nucleus, and the increased nuclear presence of p50 correlates with elevated Bcl-3 in LMP1-CTAR1-expressing cells (61, 68). It has also been suggested that Bcl-3 might contribute to p50 activation by inhibiting the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of DNA-bound p50 homodimers (7). The data presented here indicate that Bcl-3 is also regulated by LMP1-CTAR1, resulting in increased Bcl-3 mRNA and protein and nuclear translocation of Bcl-3. The data also indicate that the effects of LMP1 on Bcl-3 are linked to its effects on STAT3. STAT3 is known to be activated in EBV-infected and LMP1-expressing epithelial cells and B-cell lymphomas (6, 9, 10, 32, 55). The induction of IL-6 by LMP1 can result in the activation of STAT3, and increased IL-6 production has been detected for EBV-infected and LMP1-expressing epithelial cells (9, 10). In multiple myeloma cells, Bcl-3 transcription has been shown to be induced by IL-6 via STAT3 binding to intronic enhancers (4). However, as shown here, IL-6 transcription was slightly induced in LMP1- and CTAR1-expressing C33A cells but was induced the highest in CTAR2-expressing cells, where no EGFR or Bcl-3 induction was detected. In addition, treatment with recombinant IL-6 did not increase the serine phosphorylation of STAT3 or EGFR expression in pBabe control- or CTAR1-expressing cells (data not shown). These data indicate that LMP1-CTAR1 mediates the constitutive activation of STAT3 independently of effects on IL-6. IL-6-independent STAT3 activation by EBV has been suggested in studies where retinoic acid treatment of EBV-immortalized B lymphocytes inhibited IL-6-dependent but not constitutive STAT3 activation (67).

It is not yet clear what exact signaling pathways activate STAT3 in LMP1-expressing cells. It was previously suggested that a novel activating region between CTAR1 and CTAR2 of LMP1 interacts with JAK3 and activates the JAK/STAT signaling pathway (22). However, in EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines, the putative activating region did not mediate JAK3 association or JAK/STAT3 activation (23). In addition, in data presented here LMP1-CTAR1 is a deletion mutant, containing amino acids 1 to 231, that lacks this domain yet activates STAT3 considerably more effectively than full-length LMP1 (Fig. 3). These data indicate that the putative JAK-binding domain is not important for LMP1-mediated STAT3 activation in C33A cells. However, the inhibition of this activation by cucurbitacin, which is thought to inactivate STAT3 through inhibiting JAK2 and JAK3 activity, may indicate that the regulation of JAK activity contributes to LMP1-mediated STAT3 activation (2, 56). It will be of interest to determine how the CTAR1/TRAF complexes possibly affect STAT3 activity or the JAKs.

Several signaling pathways affected by LMP1 have been associated with STAT3 activation. Serine phosphorylation of STAT3 has been shown to be mediated by phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathways, which are both activated by LMP1-CTAR1 (11, 20, 34, 35, 50, 62). Interestingly, EGFR also activates STAT3, which suggests that a positive signaling loop of STAT3→Bcl-3→EGFR→STAT3 may be established in LMP1-expressing cells and during EBV-mediated transformation (8, 49).

A recent study suggested that LMP1 induces Bcl-3 expression through CTAR2 and the NF-κB pathway (45). This study showed that the deletion of CTAR2 or the NF-κB binding sites in the Bcl-3 promoter abolished the activity of a Bcl-3 reporter construct in LMP1-expressing Jurkat cells. The difference between that recent study and the data presented here may reflect that the construct used in that study contained amino acids 1 to 331 of the LMP1 protein, 100 amino acids longer than the CTAR1 construct (1-231) tested in our study. This region of amino acids 231 to 331 of LMP1 may have an inhibitory effect on CTAR1-mediated Bcl-3 induction. Possible inhibition by this domain is also suggested by the fact that CTAR1 alone has a higher activity for inducing Bcl-3 and EGFR than does full-length LMP1 (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Importantly, the LMP1-CTAR2 deletion mutant was tested using only a Bcl-3 reporter construct, and CTAR1 was not tested for its effects on Bcl-3 expression in cell lines. In addition, the reporter construct did not include the STAT3-binding site located approximately 1,200 bp upstream of the Bcl-3 transcriptional start site, which had the strongest interaction with STAT3 and serine-phosphorylated STAT3 in CTAR1-expressing C33A cells. This STAT3 binding site is likely important for CTAR1-mediated Bcl-3 induction.

It is intriguing that CTAR1 had an effect considerably stronger than that of full-length LMP1, although both were expressed at very similar levels. It is possible that the presence of CTAR2 downregulates the ability of CTAR1 to induce Bcl-3 and EGFR. LMP1-CTAR2 mediates downstream signaling pathways through TRAF2 or TRAF6, both of which are potential E3 ubiquitin ligases (26, 63). Since it has been shown that both EGFR and Bcl-3 can be regulated by ubiquitination, it is possible that either CTAR2-recruited TRAF2 or TRAF6 affects the LMP1-mediated induction of EGFR and Bcl-3 (24, 29, 30, 36, 60).

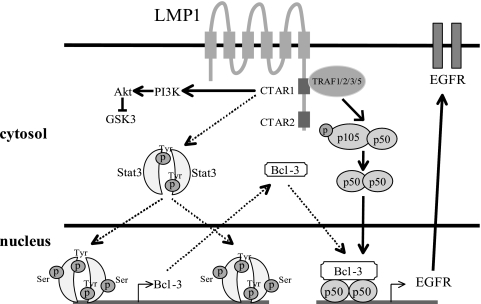

In summary, the data here suggest a model of LMP1-mediated induction of EGFR with constitutive activation of STAT3 by CTAR1 through the induction of tyrosine and serine phosphorylation of STAT3 (Fig. 6). The serine-phosphorylated STAT3 would increase Bcl-3 expression through interaction with multiple STAT-binding sites in both the promoter and introns of Bcl-3. The increased levels of Bcl-3 and the elevated levels of p50 form a transcriptional active complex to transactivate EGFR. The link between STAT3 and EGFR has also been shown by microarray data of epithelial cells overexpressing STAT3 (64). It has been suggested that the unique activation of distinct genes by LMP1-CTAR1 reflects its activation of the noncanonical pathway (33). However, the data presented here reveal that LMP1-CTAR1 has an additional mechanism to activate NF-κB through its effects on STAT3 and Bcl-3. As multiple genes have been shown to be regulated by the Bcl-3/p50-homodimer complex, it is likely that this pathway is responsible for other genes induced by LMP1 in EBV-associated tumorigenesis.

FIG. 6.

A working model for LMP1-CTAR1-mediated induction of Bcl-3 and, consequently, EGFR.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Shelton Earp for the anti-EGFR rabbit antiserum and David Everly for pBabe-LMP1, pBabe-CTAR1, and pBabe-CTAR2 constructs. We also thank Aron Marquitz and Kathy Shair for critical reviews of the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH grants CA32979 and CA103634 to N.R.-T.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 March 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkinson, P. G., H. J. Coope, M. Rowe, and S. C. Ley. 2003. Latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus stimulates processing of NF-kappa B2 p100 to p52. J. Biol. Chem. 27851134-51142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaskovich, M. A., J. Sun, A. Cantor, J. Turkson, R. Jove, and S. M. Sebti. 2003. Discovery of JSI-124 (cucurbitacin I), a selective Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling pathway inhibitor with potent antitumor activity against human and murine cancer cells in mice. Cancer Res. 631270-1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowman, T., R. Garcia, J. Turkson, and R. Jove. 2000. STATs in oncogenesis. Oncogene 192474-2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brocke-Heidrich, K., B. Ge, H. Cvijic, G. Pfeifer, D. Loffler, C. Henze, T. W. McKeithan, and F. Horn. 2006. BCL3 is induced by IL-6 via Stat3 binding to intronic enhancer HS4 and represses its own transcription. Oncogene 257297-7304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buday, L., and J. Downward. 1993. Epidermal growth factor regulates p21ras through the formation of a complex of receptor, Grb2 adapter protein, and Sos nucleotide exchange factor. Cell 73611-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buettner, M., N. Heussinger, and G. Niedobitek. 2006. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-encoded latent membrane proteins and STAT3 activation in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 449513-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmody, R. J., Q. Ruan, S. Palmer, B. Hilliard, and Y. H. Chen. 2007. Negative regulation of toll-like receptor signaling by NF-kappaB p50 ubiquitination blockade. Science 317675-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan, K. S., S. Carbajal, K. Kiguchi, J. Clifford, S. Sano, and J. DiGiovanni. 2004. Epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated activation of Stat3 during multistage skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 642382-2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, H., L. Hutt-Fletcher, L. Cao, and S. D. Hayward. 2003. A positive autoregulatory loop of LMP1 expression and STAT activation in epithelial cells latently infected with Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 774139-4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, H., J. M. Lee, Y. Zong, M. Borowitz, M. H. Ng, R. F. Ambinder, and S. D. Hayward. 2001. Linkage between STAT regulation and Epstein-Barr virus gene expression in tumors. J. Virol. 752929-2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung, J., E. Uchida, T. C. Grammer, and J. Blenis. 1997. STAT3 serine phosphorylation by ERK-dependent and -independent pathways negatively modulates its tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 176508-6516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deacon, E. M., G. Pallesen, G. Niedobitek, J. Crocker, L. Brooks, A. B. Rickinson, and L. S. Young. 1993. Epstein-Barr virus and Hodgkin's disease: transcriptional analysis of virus latency in the malignant cells. J. Exp. Med. 177339-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Decker, T., and P. Kovarik. 2000. Serine phosphorylation of STATs. Oncogene 192628-2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devergne, O., E. C. McFarland, G. Mosialos, K. M. Izumi, C. F. Ware, and E. Kieff. 1998. Role of the TRAF binding site and NF-κB activation in Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1-induced cell gene expression. J. Virol. 727900-7908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eliopoulos, A. G., J. H. Caamano, J. Flavell, G. M. Reynolds, P. G. Murray, J. L. Poyet, and L. S. Young. 2003. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent infection membrane protein 1 regulates the processing of p100 NF-kappaB2 to p52 via an IKKgamma/NEMO-independent signalling pathway. Oncogene 227557-7569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eliopoulos, A. G., M. Stack, C. W. Dawson, K. M. Kaye, L. Hodgkin, S. Sihota, M. Rowe, and L. S. Young. 1997. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded LMP1 and CD40 mediate IL-6 production in epithelial cells via an NF-kappaB pathway involving TNF receptor-associated factors. Oncogene 142899-2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Everly, D. N., Jr., B. A. Mainou, and N. Raab-Traub. 2004. Induction of Id1 and Id3 by latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus and regulation of p27/Kip and cyclin-dependent kinase 2 in rodent fibroblast transformation. J. Virol. 7813470-13478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farre, D., R. Roset, M. Huerta, J. E. Adsuara, L. Rosello, M. M. Alba, and X. Messeguer. 2003. Identification of patterns in biological sequences at the ALGGEN server: PROMO and MALGEN. Nucleic Acids Res. 313651-3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujita, T., G. P. Nolan, H. C. Liou, M. L. Scott, and D. Baltimore. 1993. The candidate proto-oncogene bcl-3 encodes a transcriptional coactivator that activates through NF-kappa B p50 homodimers. Genes Dev. 71354-1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fung, M. M., F. Rohwer, and K. L. McGuire. 2003. IL-2 activation of a PI3K-dependent STAT3 serine phosphorylation pathway in primary human T cells. Cell. Signal. 15625-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh, S., and M. Karin. 2002. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell 109(Suppl)S81-S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gires, O., F. Kohlhuber, E. Kilger, M. Baumann, A. Kieser, C. Kaiser, R. Zeidler, B. Scheffer, M. Ueffing, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1999. Latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus interacts with JAK3 and activates STAT proteins. EMBO J. 183064-3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higuchi, M., E. Kieff, and K. M. Izumi. 2002. The Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 putative Janus kinase 3 (JAK3) binding domain does not mediate JAK3 association or activation in B-lymphoma or lymphoblastoid cell lines. J. Virol. 76455-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang, F., L. K. Goh, and A. Sorkin. 2007. EGF receptor ubiquitination is not necessary for its internalization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10416904-16909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huen, D. S., S. A. Henderson, D. Croom-Carter, and M. Rowe. 1995. The Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 (LMP1) mediates activation of NF-kappa B and cell surface phenotype via two effector regions in its carboxy-terminal cytoplasmic domain. Oncogene 10549-560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huye, L. E., S. Ning, M. Kelliher, and J. S. Pagano. 2007. Interferon regulatory factor 7 is activated by a viral oncoprotein through RIP-dependent ubiquitination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 272910-2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Izumi, K. M., K. M. Kaye, and E. D. Kieff. 1997. The Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 amino acid sequence that engages tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factors is critical for primary B lymphocyte growth transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 941447-1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kieff, E., and A. B. Rickinson. 2001. Epstein-Barr virus and its replication, p. 2511-2573. In D. M. Knipe (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levkowitz, G., H. Waterman, S. A. Ettenberg, M. Katz, A. Y. Tsygankov, I. Alroy, S. Lavi, K. Iwai, Y. Reiss, A. Ciechanover, S. Lipkowitz, and Y. Yarden. 1999. Ubiquitin ligase activity and tyrosine phosphorylation underlie suppression of growth factor signaling by c-Cbl/Sli-1. Mol. Cell 41029-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levkowitz, G., H. Waterman, E. Zamir, Z. Kam, S. Oved, W. Y. Langdon, L. Beguinot, B. Geiger, and Y. Yarden. 1998. c-Cbl/Sli-1 regulates endocytic sorting and ubiquitination of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Genes Dev. 123663-3674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim, C. P., T. T. Phan, I. J. Lim, and X. Cao. 2006. Stat3 contributes to keloid pathogenesis via promoting collagen production, cell proliferation and migration. Oncogene 255416-5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lo, A. K., K. W. Lo, S. W. Tsao, H. L. Wong, J. W. Hui, K. F. To, D. S. Hayward, Y. L. Chui, Y. L. Lau, K. Takada, and D. P. Huang. 2006. Epstein-Barr virus infection alters cellular signal cascades in human nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Neoplasia 8173-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luftig, M., T. Yasui, V. Soni, M. S. Kang, N. Jacobson, E. Cahir-McFarland, B. Seed, and E. Kieff. 2004. Epstein-Barr virus latent infection membrane protein 1 TRAF-binding site induces NIK/IKK alpha-dependent noncanonical NF-kappaB activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101141-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mainou, B. A., D. N. Everly, Jr., and N. Raab-Traub. 2005. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 CTAR1 mediates rodent and human fibroblast transformation through activation of PI3K. Oncogene 246917-6924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mainou, B. A., D. N. Everly, Jr., and N. Raab-Traub. 2007. Unique signaling properties of CTAR1 in LMP1-mediated transformation. J. Virol. 819680-9692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Massoumi, R., K. Chmielarska, K. Hennecke, A. Pfeifer, and R. Fassler. 2006. Cyld inhibits tumor cell proliferation by blocking Bcl-3-dependent NF-kappaB signaling. Cell 125665-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathas, S., K. Johrens, S. Joos, A. Lietz, F. Hummel, M. Janz, F. Jundt, I. Anagnostopoulos, K. Bommert, P. Lichter, H. Stein, C. Scheidereit, and B. Dorken. 2005. Elevated NF-kappaB p50 complex formation and Bcl-3 expression in classical Hodgkin, anaplastic large-cell, and other peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Blood 1064287-4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayo, M. W., and A. S. Baldwin. 2000. The transcription factor NF-kappaB: control of oncogenesis and cancer therapy resistance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1470M55-M62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Messeguer, X., R. Escudero, D. Farre, O. Nunez, J. Martinez, and M. M. Alba. 2002. PROMO: detection of known transcription regulatory elements using species-tailored searches. Bioinformatics 18333-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller, W. E., J. L. Cheshire, A. S. Baldwin, Jr., and N. Raab-Traub. 1998. The NPC derived C15 LMP1 protein confers enhanced activation of NF-kappa B and induction of the EGFR in epithelial cells. Oncogene 161869-1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller, W. E., J. L. Cheshire, and N. Raab-Traub. 1998. Interaction of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor signaling proteins with the latent membrane protein 1 PXQXT motif is essential for induction of epidermal growth factor receptor expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 182835-2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller, W. E., H. S. Earp, and N. Raab-Traub. 1995. The Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Virol. 694390-4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller, W. E., G. Mosialos, E. Kieff, and N. Raab-Traub. 1997. Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 induction of the epidermal growth factor receptor is mediated through a TRAF signaling pathway distinct from NF-κB activation. J. Virol. 71586-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mosialos, G., M. Birkenbach, R. Yalamanchili, T. VanArsdale, C. Ware, and E. Kieff. 1995. The Epstein-Barr virus transforming protein LMP1 engages signaling proteins for the tumor necrosis factor receptor family. Cell 80389-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakamura, H., C. Ishii, M. Suehiro, A. Iguchi, K. Kuroda, K. Shimizu, N. Shimizu, K. I. Imadome, M. Yajima, and S. Fujiwara. 2008. The latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) encoded by Epstein-Barr virus induces expression of the putative oncogene Bcl-3 through activation of the nuclear factor-kappaB. Virus Res. 131170-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nolan, G. P., T. Fujita, K. Bhatia, C. Huppi, H. C. Liou, M. L. Scott, and D. Baltimore. 1993. The bcl-3 proto-oncogene encodes a nuclear IκB-like molecule that preferentially interacts with NF-κB p50 and p52 in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 133557-3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohno, H., M. Nishikori, Y. Maesako, and H. Haga. 2005. Reappraisal of BCL3 as a molecular marker of anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Int. J. Hematol. 82397-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paine, E., R. I. Scheinman, A. S. Baldwin, Jr., and N. Raab-Traub. 1995. Expression of LMP1 in epithelial cells leads to the activation of a select subset of NF-κB/Rel family proteins. J. Virol. 694572-4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park, O. K., T. S. Schaefer, and D. Nathans. 1996. In vitro activation of Stat3 by epidermal growth factor receptor kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9313704-13708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plaza-Menacho, I., T. van der Sluis, H. Hollema, O. Gimm, C. H. Buys, A. I. Magee, C. M. Isacke, R. M. Hofstra, and B. J. Eggen. 2007. Ras/ERK1/2-mediated STAT3 Ser727 phosphorylation by familial medullary thyroid carcinoma-associated RET mutants induces full activation of STAT3 and is required for c-fos promoter activation, cell mitogenicity, and transformation. J. Biol. Chem. 2826415-6424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Raab-Traub, N. 2002. Epstein-Barr virus in the pathogenesis of NPC. Semin. Cancer Biol. 12431-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sadler, R. H., and N. Raab-Traub. 1995. The Epstein-Barr virus 3.5-kilobase latent membrane protein 1 mRNA initiates from a TATA-less promoter within the first terminal repeat. J. Virol. 694577-4581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saito, N., G. Courtois, A. Chiba, N. Yamamoto, T. Nitta, N. Hironaka, M. Rowe, N. Yamamoto, and S. Yamaoka. 2003. Two carboxyl-terminal activation regions of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 activate NF-kappaB through distinct signaling pathways in fibroblast cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 27846565-46575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salomon, D. S., R. Brandt, F. Ciardiello, and N. Normanno. 1995. Epidermal growth factor-related peptides and their receptors in human malignancies. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 19183-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shair, K. H., K. M. Bendt, R. H. Edwards, E. C. Bedford, J. N. Nielsen, and N. Raab-Traub. 2007. EBV latent membrane protein 1 activates Akt, NFkappaB, and Stat3 in B cell lymphomas. PLoS Pathog. 3e166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi, X., B. Franko, C. Frantz, H. M. Amin, and R. Lai. 2006. JSI-124 (cucurbitacin I) inhibits Janus kinase-3/signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 signalling, downregulates nucleophosmin-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), and induces apoptosis in ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma cells. Br. J. Haematol. 13526-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soni, V., E. Cahir-McFarland, and E. Kieff. 2007. LMP1 TRAFficking activates growth and survival pathways. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 597173-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thornburg, N. J., R. Pathmanathan, and N. Raab-Traub. 2003. Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB p50 homodimer/Bcl-3 complexes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 638293-8301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thornburg, N. J., and N. Raab-Traub. 2007. Induction of epidermal growth factor receptor expression by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 C-terminal-activating region 1 is mediated by NF-κB p50 homodimer/BCL-3 complexes. J. Virol. 8112954-12961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Viatour, P., E. Dejardin, M. Warnier, F. Lair, E. Claudio, F. Bureau, J. C. Marine, M. P. Merville, U. Maurer, D. Green, J. Piette, U. Siebenlist, V. Bours, and A. Chariot. 2004. GSK3-mediated BCL-3 phosphorylation modulates its degradation and its oncogenicity. Mol. Cell 1635-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watanabe, N., T. Iwamura, T. Shinoda, and T. Fujita. 1997. Regulation of NFKB1 proteins by the candidate oncoprotein BCL-3: generation of NF-kappaB homodimers from the cytoplasmic pool of p50-p105 and nuclear translocation. EMBO J. 163609-3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wierenga, A. T., I. Vogelzang, B. J. Eggen, and E. Vellenga. 2003. Erythropoietin-induced serine 727 phosphorylation of STAT3 in erythroid cells is mediated by a MEK-, ERK-, and MSK1-dependent pathway. Exp. Hematol. 31398-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xia, Z. P., and Z. J. Chen. 2005. TRAF2: a double-edged sword? Sci. STKE 2005pe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang, J., M. Chatterjee-Kishore, S. M. Staugaitis, H. Nguyen, K. Schlessinger, D. E. Levy, and G. R. Stark. 2005. Novel roles of unphosphorylated STAT3 in oncogenesis and transcriptional regulation. Cancer Res. 65939-947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yarden, Y., and M. X. Sliwkowski. 2001. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2127-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Young, L., C. Alfieri, K. Hennessy, H. Evans, C. O'Hara, K. C. Anderson, J. Ritz, R. S. Shapiro, A. Rickinson, E. Kieff, et al. 1989. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus transformation-associated genes in tissues of patients with EBV lymphoproliferative disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 3211080-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zancai, P., R. Cariati, M. Quaia, M. Guidoboni, S. Rizzo, M. Boiocchi, and R. Dolcetti. 2004. Retinoic acid inhibits IL-6-dependent but not constitutive STAT3 activation in Epstein-Barr virus-immortalized B lymphocytes. Int. J. Oncol. 25345-355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang, Q., J. A. Didonato, M. Karin, and T. W. McKeithan. 1994. BCL3 encodes a nuclear protein which can alter the subcellular location of NF-κB proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 143915-3926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zheng, X., L. Hu, F. Chen, and B. Christensson. 1994. Expression of Ki67 antigen, epidermal growth factor receptor and Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein (LMP1) in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer B 30B290-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]