Abstract

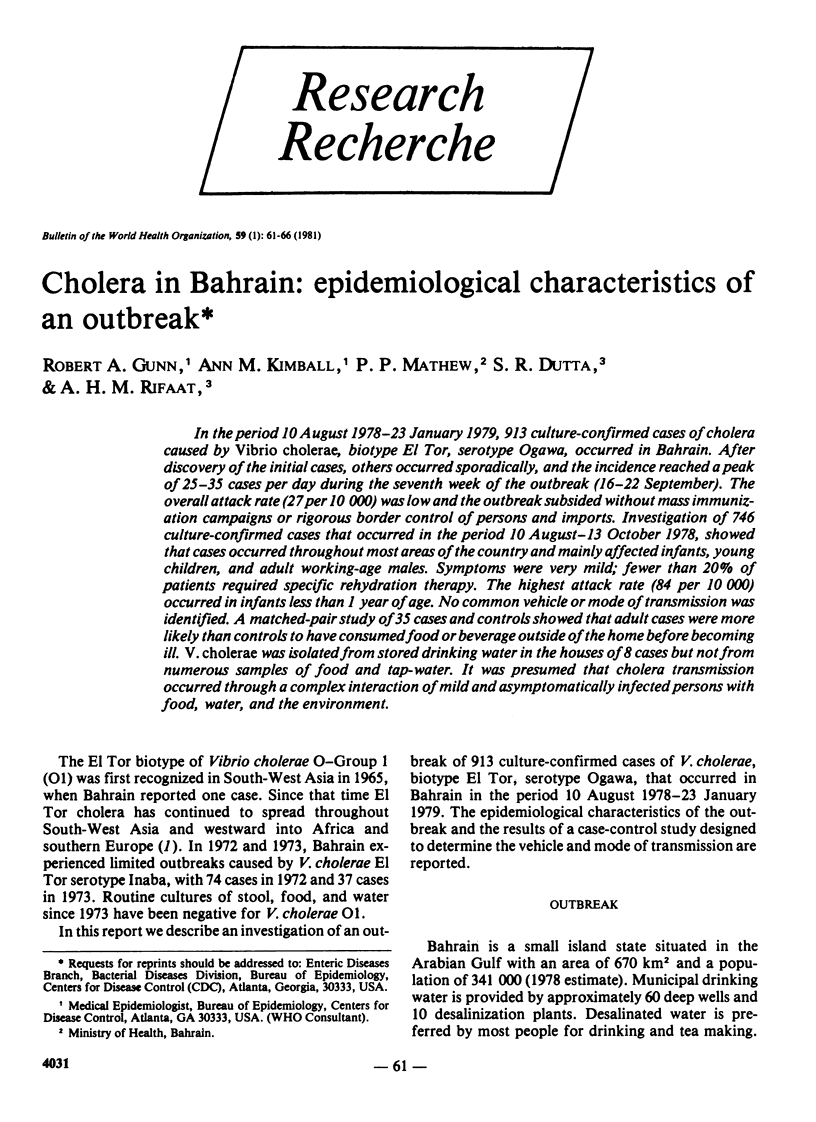

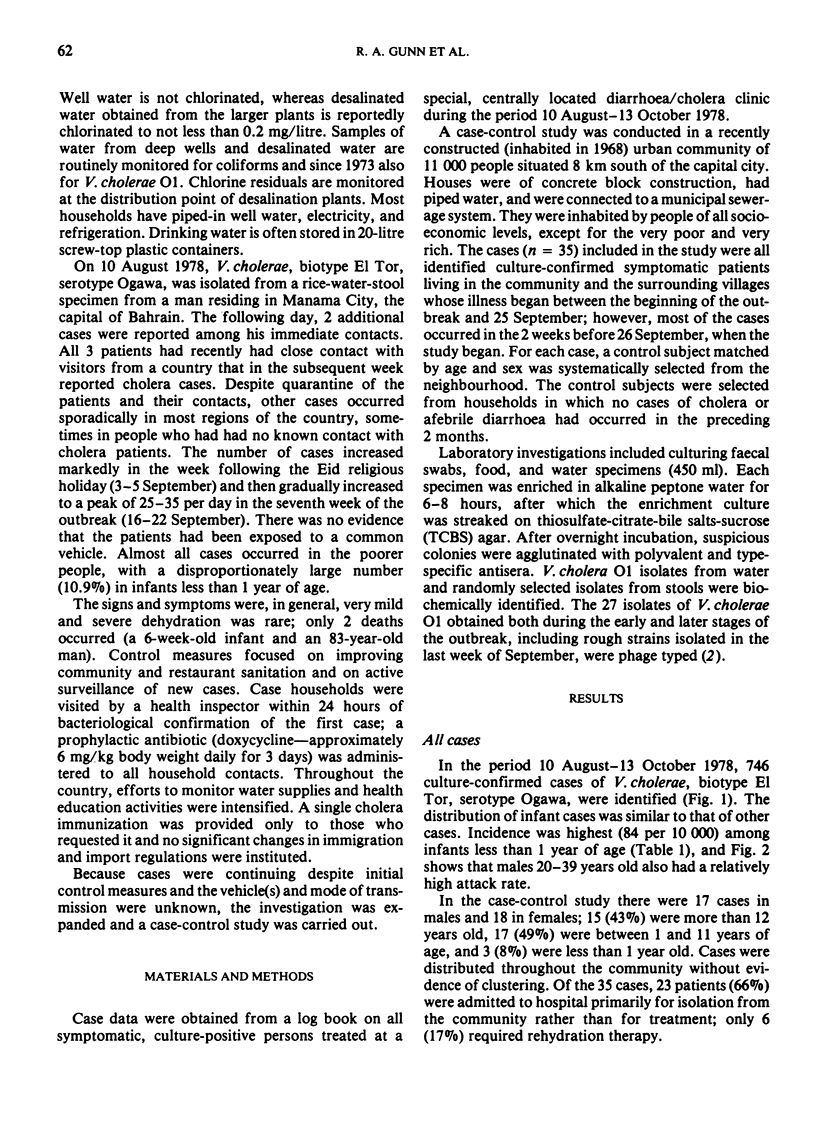

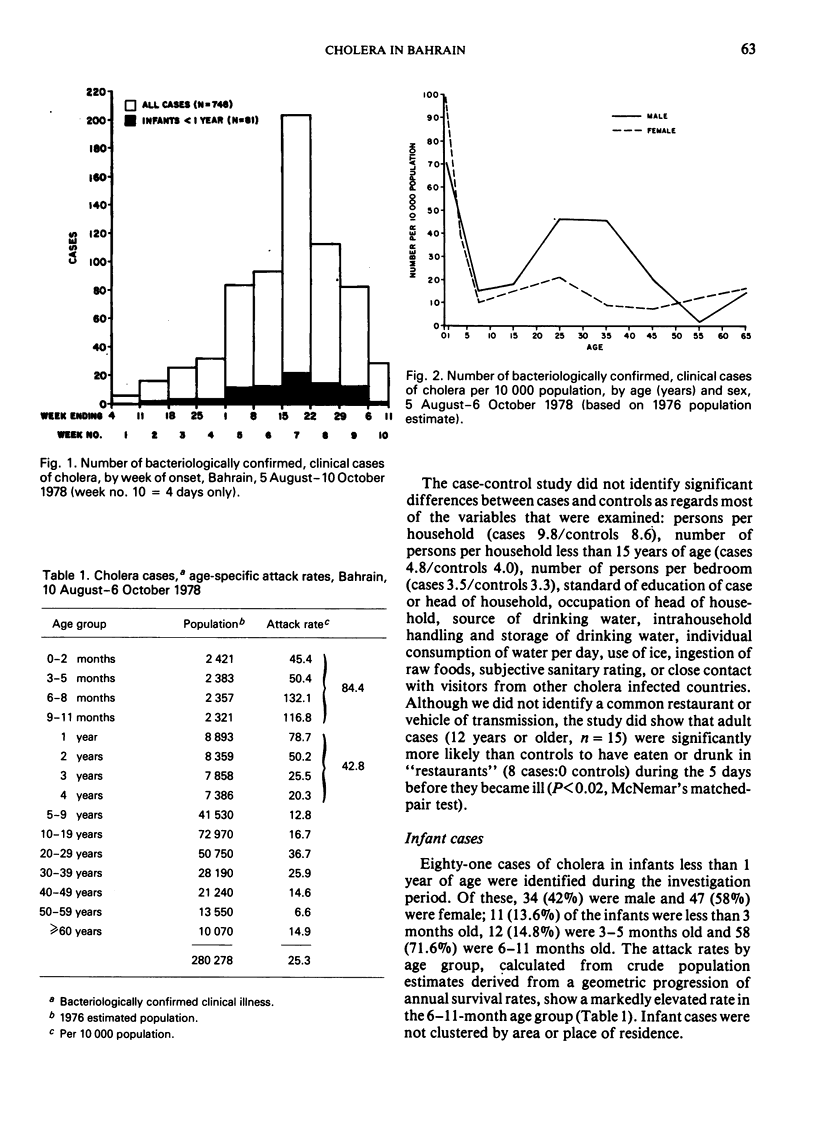

In the period 10 August 1978-23 January 1979, 913 culture-confirmed cases of cholera caused by Vibrio cholerae, biotype El Tor, serotype Ogawa, occurred in Bahrain. After discovery of the initial cases, others occurred sporadically, and the incidence reached a peak of 25-35 cases per day during the seventh week of the outbreak (16-22 September). The overall attack rate (27 per 10 000) was low and the outbreak subsided without mass immunization campaigns or rigorous border control of persons and imports. Investigation of 746 culture-confirmed cases that occurred in the period 10 August—13 October 1978, showed that cases occurred throughout most areas of the country and mainly affected infants, young children, and adult working-age males. Symptoms were very mild; fewer than 20% of patients required specific rehydration therapy. The highest attack rate (84 per 10 000) occurred in infants less than 1 year of age. No common vehicle or mode of transmission was identified. A matched-pair study of 35 cases and controls showed that adult cases were more likely than controls to have consumed food or beverage outside of the home before becoming ill. V. cholerae was isolated from stored drinking water in the houses of 8 cases but not from numerous samples of food and tap-water. It was presumed that cholera transmission occurred through a complex interaction of mild and asymptomatically infected persons with food, water, and the environment.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baine W. B., Mazzotti M., Greco D., Izzo E., Zampieri A., Angioni G., Di Gioia M., Gangarosa E. J., Pocchiari F. Epidemiology of cholera in Italy in 1973. Lancet. 1974 Dec 7;2(7893):1370–1374. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)92233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S., Mukerjee S. Bacteriophage typing of Vibrio eltor. Experientia. 1968 Mar 15;24(3):299–300. doi: 10.1007/BF02152832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake P. A., Rosenberg M. L., Costa J. B., Ferreira P. S., Guimaraes C. L., Gangarosa E. J. Cholera in Portugal, 1974.I. Modes of transmission. Am J Epidemiol. 1977 Apr;105(4):337–343. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodgame R. W., Greenough W. B. Cholera in Africa: a message for the West. Ann Intern Med. 1975 Jan;82(1):101–106. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-82-1-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn R. A., Kimball A. M., Pollard R. A., Feeley J. C., Feldman R. A., Dutta S. R., Matthew P. P., Mahmood R. A., Levine M. M. Bottle feeding as a risk factor for cholera in infants. Lancet. 1979 Oct 6;2(8145):730–732. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90653-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine R. J., Khan M. R., D'Souza S., Nalin D. R. Failure of sanitary wells to protect against cholera and other diarrhoeas in Bangladesh. Lancet. 1976 Jul 10;2(7976):86–89. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)92299-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre R. C., Tira T., Flood T., Blake P. A. Modes of transmission of cholera in a newly infected population on an atoll: implications for control measures. Lancet. 1979 Feb 10;1(8111):311–314. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90719-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer A., Woodward W. E. The influence of protected water supplies on the spread of classical-Inaba and El Tor-Ogawa cholera in rural East Bengal. Lancet. 1972 Nov 11;2(7785):985–987. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)92401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]