Abstract

Ion channels are involved in normal physiological processes, and in the pathology of various diseases. In this study, we investigated the presence and potential function of TRPM7 channels in the growth and proliferation of FaDu and SCC25 cells, two common human head and neck squamous carcinoma cell lines, using a combination of patch-clamp recording, Western blotting, immunocytochemistry, small interference RNA (siRNA), fluorescent Ca2+ imaging, and cell counting techniques. Although voltage-gated K+ currents were recorded in all cells, none of FaDu cells express voltage-gated Na+ or Ca2+ currents. Perfusion of cells with NMDA or acidic solution did not activate inward currents, indicating a lack of NMDA receptor and acid-sensing channels. Lowering extracellular Ca2+, however, induced a large non-desensitizing current reminiscent of Ca2+-sensing cation current or TRPM7 current previously described in other cells. This Ca2+-sensing current can be inhibited by Gd3+, 2-APB, or intracellular Mg2+, consistent with the TRPM7 current being activated. Immunocytochemistry, Western blot, and RT-PCR detected the expression of TRPM7 protein and mRNA in these cells. Transfection of FaDu cells with TRPM7-siRNA significantly reduced the expression of TRPM7 mRNA and protein, as well as the amplitude of the Ca2+-sensing current. Furthermore, we found that Ca2+ is critical for the growth and proliferation of FaDu cells. Blockade of TRPM7 channels by Gd3+ and 2-APB, or suppression of TRPM7 expression by siRNA inhibited the growth and proliferation of these cells. Similar to FaDu cell, SCC25 cells also express TRPM7-like channels. Suppressing the function of these channels inhibited the prolifereation of SCC25 cells.

Keywords: TRPM7, ion channel, head and neck tumor, calcium, proliferation

Introduction

For both excitable and non-excitable cells, Ca2+ influx is critical for normal cell function. Unlike excitable cells where voltage-gated Ca2+ channels play an important role in Ca2+ entry, non-excitable cells usually lack voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. The main pathway of Ca2+ entry in these cells appears to be store-operated Ca2+ channels (SOCs) or Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation channels 1–3, of which the transient receptor potential (TRP) channels have recently be recognized as a major candidate. The TRP superfamily of ion channels are divided into six subfamilies according to their sequence homology: TRPC, TRPM, TRPV, TRPP, TRPML, and TRPA 4–6. TRPM subfamily of TRP channels has eight members, TRPM1-8. Different members of the TRPM subfamily appear to have different gating and regulatory mechanisms, along with different ion selectivity and expression patterns. By mediating cations entry as well as membrane depolarization, activations of TRPM subfamily of ion channels have profound influence on various physiological and pathological processes 6,7.

Since Ca2+ is an essential regulator of the cell cycle and proliferation 8,9, it is of importance to identify Ca2+ entry pathways in non-excitable cells, including tumor cells. Although Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel (CRAC), one of the store-operated channels, was initially considered to be the primary pathway for Ca2+ entry in non-excitable cells 1,10, more recent studies, have recognized the importance of TRPM7 channels in numerous Ca2+-dependent processes 11–13. In addition, activations of TRPM7 channels have been shown to be involved in cellular Mg2+ homeostasis, diseases caused by abnormal magnesium absorption, and in anoxia-induced neuronal cell death 14–16. However, the presence and potential function of TRPM7 channels in head and neck tumor cells are unknown.

In this study, we examined presence and potential role of TRPM7 channels in the growth and proliferation of FaDu cells, a common human head and neck squamous carcinoma. Our data strongly suggest that functional TRPM7 channels are expressed in FaDu cells. Activation of TRPM7 channels is critical for the growth and proliferation of these tumor cells.

Materials and Methods

Cells

FaDu cells (ATCC catalog No. HTB-43), a cell line of human hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, were cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential medium (E-MEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere. Cells were passaged twice weekly and plated on 35 mm round poly-L-ornithine coated dishes, and were used for electrophysiological recordings, Western blot, and fluorescent imaging 3–5 days after plating. SCC-25 cells (ATCC Cat. No. CRL-1628), a cell line of human thyroid squamous cell carcinoma, were cultured in 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco’s Minimum Essential Medium and F-12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 400 ng/mL hydrocortisone at 37° C with 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere. Cells were passaged once a week with medium renewal twice weekly. Cells were plated on 35 mm round poly-L-ornithine coated dishes, and were used for electrophysiological recordings, Western blot, and fluorescent imaging 3–5 days after plating.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were performed as described in our previous studies 17. Patch electrodes were constructed from thin-welled borosilicate glass (WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA) on a two-stage puller (PP83 Narishige, Tokyo), and had resistances of 1.5–3 Mω when filled with the intracellular solution. Whole-cell currents were recorded using Axopatch 200B amplifier with pCLAMP 9.2 software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Currents were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 5 kHz using Digidata 1322A. Data were eliminated from statistical analysis when access resistance was larger than 10 Mω or leak current larger than 100 pA at −60 mV. A multi-barrel perfusion system (SF-77, Warner Instrument Co., CT, USA) was employed to achieve a rapid exchange of external solutions. All experiments were performed at room temperature (~22°C). Unless otherwise stated, the voltage-clamp recordings were performed 5 minutes after the formation of whole cell configuration to avoid the initial “rundown” of the current. For most electrophysiological recordings, a holding potential of −60 mV was employed.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was performed as described previously 18. Cells were seeded on 25 mm coverslips. After 3 days, they were washed with PBS and fixed in 10% formarlin for 15 min. Cells were then washed 3 times with PBS and immediately quenched in ethanol and acetic acid (2:1) solution for 5 min (−20°C), followed by permeabilization with 3% Triton X-100/PBS at room temperature. Cells were then incubated in PBS containing 2% goat serum (Vector, catalog No. S-1000) and 1% BSA (Sigma, catalog No. B-4287) for 30 minutes, followed by overnight incubation with 1:100 dilution of TRPM7 primary antibody (Abgent, San Diego, CA) at 4°C. After extensive wash in PBS, cells were incubated with 1:750 dilution of Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antiserum (Jackson Immunoresearch, Plymouth, PA. USA.) for 2h at room temperature. Coverslips were then mounted with mounting medium containing 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Immunostained cells were visualized under a Leica microscope equipped with epifluorescent illumination. Excitation/emission wavelengths of 580nm/630nm were used to visualize TRPM7 labeled cells. Images were collected using an Optronics DEI-750 3-chip camera equipped with a BQ 8000 sVGA frame grabber and analyzed using an image analysis system (Bioquant, Nashville, TN, USA).

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described in our previous studies 19. Cells grown in 35 mm dishes were harvested with 100 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitor, pH 7.5). After centrifugation at 12000×g for 30 min (4°C), the supernatant was collected. The supernatant was then mixed with equal amount of Laemmli sample buffer and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The samples were resolved by 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate -polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by electrotransfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories). For visualization, blots were probed with antibodies against TRPM7 (1:250), α-tubulin (Abcam, MA) or actin (1:2000, Abcam,), and detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology Inc., MA, USA) and an enhanced luminescence kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, NJ) followed by photograph with Kodak BioMax chemiluminescence film (Kodak, NY).

RNA preparation and RT-PCR

Isolation of total RNAs was performed using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First strand DNA was generated from total RNA of 0.5 μg using Oligo(dT)15 and reverse transcriptase SuperScript II (Invitrogen, CA, USA) with a reaction volume of 20 μl. An oligonucleotide primer pair was synthesized over regions specific for human TRPM7 cDNA (GenBank accession number NM_017672). A primer pair for the detection of human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; GenBank accession number M_33197) was used as the internal control. Negative control in PCR reaction was performed by replacing cDNA with ultra-pure water. RT-PCR amplification was performed with Advantage cDNA polymerase mix (Clontech Laboratories, CA) using a thermal cycler (MJ Mini, Bio-Rad laboratories). The protocol for PCR amplification consists of denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, 29 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec, annealing at 57 °C for 15 sec, and extension at 72 °C for 30 sec. Products were separated by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The primers used for RT-PCR were: TRPM7 forward (5'-CCATACCATATTCTCCAAGGTTCC-3'), TRPM7 reverse (5'-CATTCCTCTTCAGATCTGGAAGTT-3'); GAPDH forward (5’-ATGCTGGTGCTGAGTATGTCGTG-3’), GAPDH reverse (5’-TTACTCCTTGGAGGCCATGTAGG-3’).

siRNA silencing

To construct a plasmid for TRPM7 gene silencing, first two oligonucleotides were annealed, and inserted into pSilencer 1.0-U6 siRNA expression vector (Ambion, TX, USA). Then, a fragment cut with BamHI was excised and inserted into BamHI site of pCAGGS-eGFP (kindly provided by Dr. J. Miyazaki) to express both enhanced green fluorescence protein (eGFP) and short hairpin RNA 20. The oligonucleotide sequences were: 5’-GTCTTGCCATGAAATACTCTTCAAGAGAGAGTATTTCATGGCAAGACTTTTTT-3’ for the sense strand and 5’-AATTAAAAAAGTCTTGCCATGAAATACTCTCTCTTGAAGAGTATTTCATGGCAAGACGGCC-3’ for the antisense strand 13. As a negative control, a fragment cut with BamHI from pSilencer 1.0-U6 siRNA expression vector was inserted into pCAGGS-eGFP. Transfection was performed with Fugene 6 tranfection reagent (Roche Applied Science, IN, USA). Cells were used for electrophysiology, immumocytochemistry, Western blotting, and RT-PCR 72 h after siRNA transfection.

For the study of cell proliferation, siPORT NeoFX transfection agent (Ambion) was used following the manufacturer’s suggestions. Briefly, FaDu or SCC25 cells cultured in 25 cm2 flask were trypsinized and diluted to ~1×105 cells per ml. siPORT NeoFX and TRPM7-siRNA (Ambion) were diluted separately (1:20) in Opti-MEM I Reduced-Serum Medium (Invitrogen) for a final volume of 50 μl per well. Following 10 min incubation, transfection complexes were formed by combining the diluted siPORT NeoFX and siRNA and incubated for 10 more min. The media was dispensed with transfection complexes into empty wells of a 24-well plate, and cell suspensions were then pipetted into the wells. Final siRNA concentrations and cell numbers for each well were 30 nM and 1×105. Cells were used for cell count and LDH assays 72 hours after the transfection. A negative control siRNA (Ambion, Cat. 4611) was used to verify that the effect seen with TRPM7-siRNA was not due to the transfection process. The siRNA target sequence for human TRPM7 was the same as that described above.

Ca2+ - imaging

Fluorescent Ca2+-imaging was performed as described previously 17. FaDu cells grown on glass coverslips were washed 3 times with standard extracellular solution and incubated with 10 μM fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester for 45 minutes at room temperature. Coverslips with fura-2-laoded cells were then transferred to a perfusion chamber on an inverted microscope (Nikon). Cells were illuminated using a xenon lamp (75W) and observed with a ×40 UV fluor oil-immersion objective lens (Nikon). Video images were obtained using a CCD camera (Sensys KAF 1401, Photometrics). Digitized images were acquired, stored, and analyzed in a computer controlled by Axon Imaging Workbench software (AIW2.1, Axon Instruments). The shutter and filter wheel were also controlled by AIW to allow timed illumination of cells at either 340 or 380nm excitation wavelengths. Fura-2 fluorescence was detected at an emission wavelength of 510nm. Ratio images were analyzed by averaging pixel ratio values in circumscribed regions of cells in the field of view.

Cell count

Cell counting was performed as described previously 13. 24-well plates were employed for cell counting experiment. The initial number of FaDu or SCC25 cells was adjusted to ~1×105 cells per well in 1 ml culture medium. Test chemicals were added into culture medium at the time of plating. 72 hours after the plating, cells were re-suspended and counted using a Hemocytometer. For medium with different concentrations of free [Ca2+], appropriate amount of EGTA was added to yield the right concentrations of free Ca2+ using Cabuffer program. pH in each medium was re-adjusted to 7.2 after adding EGTA.

LDH assay

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay was performed as described 17. 72 hours after the plating, cells were washed 3 times with Neurobasal medium. 50 μl of medium was collected from each well for background LDH measurement. Triton X-100 was then added to each well (final concentration of 0.5%) to permeabilize the cells for obtaining the maximal releasable LDH, which is proportional to total number of cells in each well. After 30 min, 50 μl sample of medium was collected from each well and placed into 96-well plates. 50 μl of LDH assay mixture from Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (Roche Applied Science) was then added to each sample. Following a 30 min incubation at room temperature (24°C), the absorbance at 492 nm was read on a multi-well plate reader (Spectra Max Plus, Molecular Devices, CA, USA). The background absorbance at 620 nm was subtracted from the 492 nm absorbance.

Solutions and Chemicals

Standard extracellular solution contained (in mM): 140 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 20 HEPES, 10 glucose (pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH; 320–335 mOsm). For divalent-free external solutions, CaCl2 and MgCl2 were removed from the solution with osmolarity adjusted with additional glucose. Patch electrodes contained (in mM): 140 CsF, 35 CsOH, 10 HEPES, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 11 EGTA, 2 TEA, 4 MgATP (pH 7.25 adjusted with CsOH, 290–300 mOsm). For recordings of voltage-gated K+ current, CsF was replaced with KF. For Mg2+-free pipette solution, Mg2+ and MgATP were omitted from the solution. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA); gadolinium chloride, 1-heptamol, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were from Sigma.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. Student’s t-tests, and ANOVA were employed as appropriate for the analysis of statistical significance. Dose-response curves were fitted to Hill equation using the SigmaPlot 8.0 software.

Results

Lowering extracellular Ca2+ activates a slow non-desensitizing inward current in FaDu cells

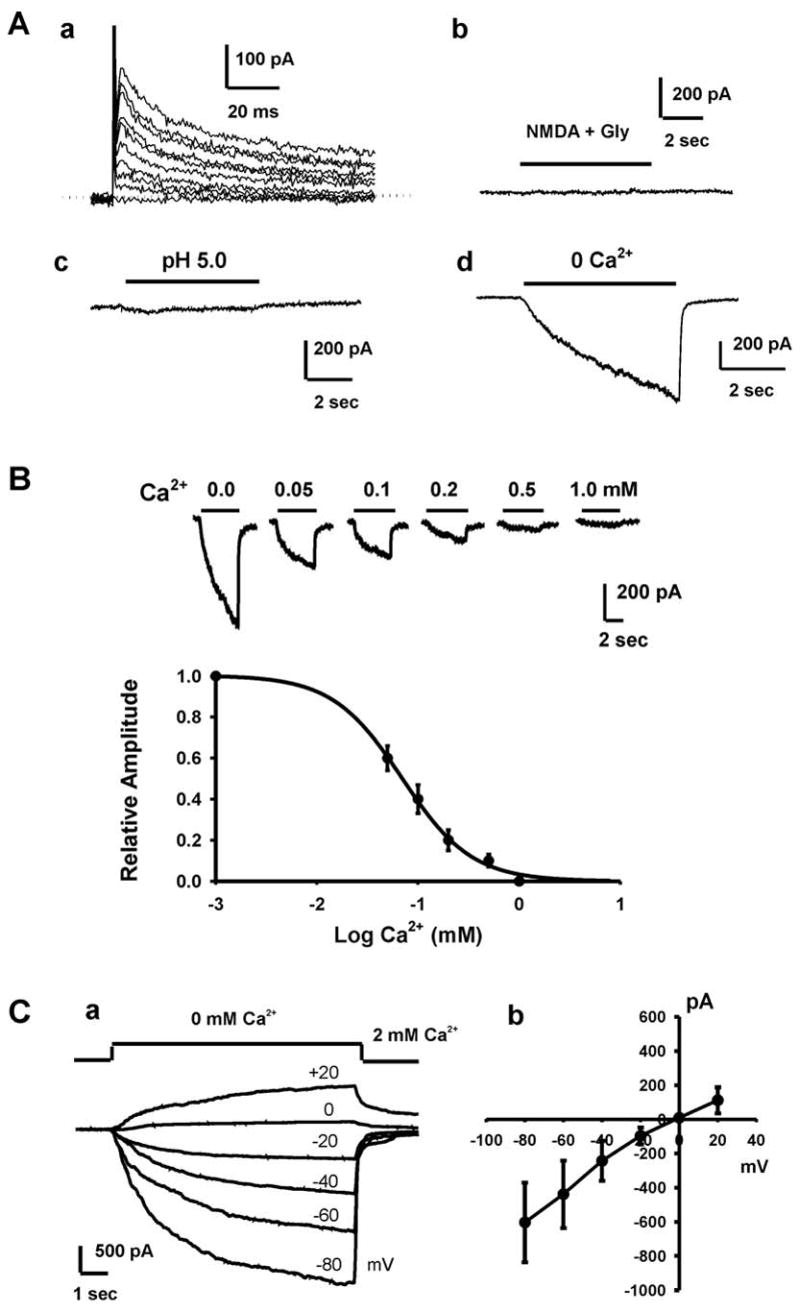

To determine the presence and potential function of ion channels in the growth and proliferation of head and neck tumor cells, we used patch-clamp technique to detect the presence of membrane current in FaDu cells, a cell line of human hypopharyngeal carcinoma 21,22. We first examined whether these cells have voltage-gated Na+, Ca2+, or K+ current. From a holding potential of −60 mV, membrane was gradually depolarized from −80 mV to +80 mV by a series of voltage pulses at an increment of +10 mV. As shown in Fig. 1A-a, no sign of any inward current was activated by the depolarizing pulses (n > 10), indicating a lack of voltage-gated Na+ and Ca2+ channels in these cells. However, in all cells recorded, membrane depolarization activated typical outward K+ current as in the majority of excitable and non-excitable cells. Perfusion of FaDu cells with 100 μM NMDA plus 3 μM glycine or acidic solutions (pH 5.0) did not activate substantial inward current (Fig. 1A-b & 1A-c, n = 10), indicating the lack of NMDA channels and acid-sensing ion channels 23 in these cells.

Fig. 1. Activation of Ca2+-sensitive currents in FaDu cells.

A, a. Representative traces showing the presence of outward K+ currents in FaDu cells. Currents were activated by a series of depolarizing voltage pulses from −80 mV to +80 mV at an increment of +20 mV. Holding potential was −60 mV. No obvious inward current was detected at any potential, indicating the lack of voltage-gated Na+ and Ca2+ channels. b. Representative trace showing the lack of NMDA currents in FaDU cells. Following a stable baseline recording, cells were perfused with NMDA (100 μM) and its co-agonist glycine (3 μM). c. Representative trace showing the lack of acid-activated current in FaDu cells. d. A rapid drop of [Ca2+]o from 2 mM to 0 mM (nominally free) evoked a slow non-desensitizing inward current that rapidly recovered upon restoration of [Ca2+]o. Holding potential was −60 mV. B, Representative current traces and summary data showing concentration-dependent inhibition of the inward current in FuDu cells by external Ca2+. Dose-response curve was fit by Hill equation with an average IC50 of 0.07 ± 0.02 mM (n = 9). C, a. Representative traces showing the Ca2+-sensing current activated at different membrane potentials. Currents were activated by step reductions of [Ca2+]o from 2 to 0 mM over a range of holding potentials from −80 to +20 mV. Pipette solution contains 0 mM Mg2+. b. Summary data showing the current-voltage relationship (I–V curve) of the Ca2+-sensing current (n = 7).

Recent studies have suggested that TRPM7 is one of the ubiquitously expressed ion channels in both excitable and non-excitable cells 15,24–28. Because of their Ca2+ permeability and lack of voltage-dependent gating, they are well designed to contribute to numerous Ca2+-dependent cell processes in non-excitable cells. For this reason, we explored the possibility that FaDu cells express TRPM7 channels. In the presence of physiological concentrations of both Ca2+ and Mg2+, a rapid drop of extracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]o) from 2 mM to 0 mM (nominally free) evoked a slow non-desensitizing inward current (Fig. 1A-d). The amplitude of this current measured right after the formation of whole-cell configuration ranged from 138.69 to 1545.08 pA (mean 642.12 ± 99.42 pA, n = 14). When the bath solution was changed to both Ca2+ and Mg2+-free, and Mg2+ was omitted from the pipette solution, the range of this current amplitude was 256.37 to 4491.31pA (mean 898.19 ± 103.60 pA, n = 49). This Ca2+-sensitive inward current is reminiscent of the Ca2+-sensing non-selective cation current (csNSC) in CNS neurons and HEK293 cells 29, which was late identified as largely carried by TRPM7 channels 16. With intracellular solution containing normal Mg2+, the amplitude of the inward current in FaDu cells gradually decreased following the formation of the whole cell configuration. In most cells, the currents became stable ~10 min following the break-in of the cell (data not shown).

Since the amplitude of this current is closely related to [Ca2+]o, we next recorded the currents activated at different [Ca2+]o to construct a complete dose-response relationship. As shown in Fig 1B, the maximal inward current was recorded in the absence of the extracellular Ca2+ and the current gradually decreased with increasing concentrations of Ca2+. A concentration-response analysis revealed an IC50 of 0.07 ± 0.02 mM for Ca2+ blockade of this current (Fig. 1B, n = 9).

To determine whether this Ca2+-sensing current shows any voltage dependency, currents activated by lowering [Ca2+]o from 2.0 mM to 0 mM were recorded over a range of holding potentials from −80 to +20 mV. As shown in Fig. 1C-a, the whole-cell currents reversed near 0 mV (n = 7), and the current-voltage relationship appears to be linear over the voltage range tested, illustrating a lack of voltage dependence (Fig. 1C-b).

Pharmacological characterization of the Ca2+-sensing current in FaDu cells

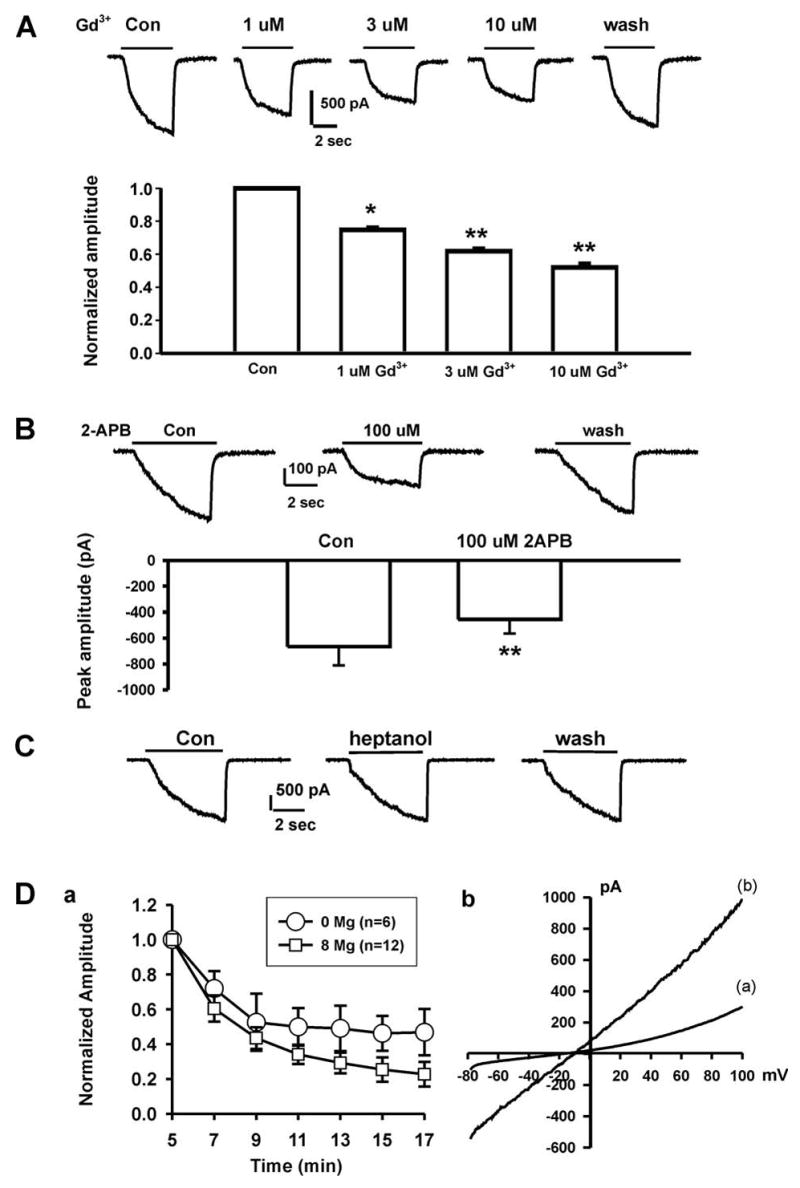

Previous studies have shown that Gd3+ is a potent non-specific blocker for cloned or native TRPM7 channels 13,16,30,31. In the presence of 1, 3, or 10 μM Gd3+ in the bath solution, the amplitude of the Ca2+-sensing current in FaDu cells was decreased by 24.53 ± 9.08% (n = 6, p<0.05), 36.23 ± 7.12% (n = 9, p<0.01), and 46.66 ± 10.89% (n = 9, p<0.01) respectively (Fig. 2A). This potency of Gd3+ inhibition of the Ca2+-sensing inward current in FaDu cells is consistent with the effect of Gd3+ on Mg2+-inhibitable cation channels (MIC) or TRPM7 channels 13,16,31,32.

Fig. 2. Pharmacological characterization of the Ca2+-sensing current in FaDu cells.

A, Dose-dependent inhibition of the Ca2+-sensing current by Gd3+. Representative traces of the Ca2+-sensing currents in the absence and presence of different concentrations of Gd3+. Holding potential = −60 mV. Pipette solution contained no Mg2+. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01. B, Effect of 2-APB on the Ca2+-sensing current. Representative traces and summary bar graph showing the Ca2+-sensing current in the absence and presence of 100 μM 2-APB, ** p<0.01. C, Representative current traces showing the lack of inhibition on the Ca2+-sensing current by 1 mM Heptanol. D, a. Time-dependent change in the amplitude of the Ca2+-sensing current with pipette solution containing either 8 or 0 mM of Mg2+. Currents were induced by a drop of [Ca2+]o from 2 mM to 0 mM at −60 mV. The decrease of the current amplitude with time was significantly greater with pipette solution containing 8 mM Mg2+ (p<0.05, two-way ANOVA). b. Current-voltage relationship of the Ca2+-sensing current in the presence and absence of physiological concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+. Currents were activated by 400 ms voltage-ramp pulses ranging from −80 to +100 mV in the presence (a) and absence (b) of 2 mM Ca2+ and 1 mM Mg2+ in the extracellular solutions. Note that even in the presence of normal Ca2+ and Mg2+, substantial current can still be activated at negative membrane potentials.

Next, we test the effect of 2-APB on the Ca2+ sensing current. Recent studies have shown that, over a concentration range of 10 - 100 μM, 2-APB has broad inhibitory effects on TRP superfamily including TRPM7 channels 13,33–36. In the presence of 100 μM 2-APB, the Ca2+-sensing inward current in FaDu cells was inhibited by 31.80 ± 6.18% (Fig. 2B, n = 15, p<0.01). The effect of 2-APB was readily reversible upon washout of 2-APB. The inhibition by 2-APB further suggests that the Ca2+-sensing current in FaDu cells might be carried by TRP channels.

Lowering extracellular Ca2+ is known to activate hemi-gap junction channels in various cell types 37. To rule out the possible involvement of the hemi-gap junction channel in the current recorded in FaDu cells, the effect of 1-heptanol, a commonly used inhibitor for gap junction channels 38,39, was tested on the Ca2+-sensing current in FaDu cells. As shown in Fig. 2C, bath perfusion of 1 mM 1-heptanol was not effective in modulating the Ca2+-sensing currents (n = 5), indicating the lack of an involvement of the hemi-gap junction channels in the Ca2+-sensing current in FaDu cells.

Nadler et al 15 found that TRPM7 channel activity in HEK293 cells was strongly suppressed by internal Mg2+ in millimolar concentration range. Similarly, Kozak et al 40 found that MIC (or TRPM7) channels in rat basophilic leukemia cells was inhibited by internal divalent cations. The TRPM7-like current in rat brain microglia was also inhibited by the intracellular Mg2+ 25. In Jurkat E6-1 human leukemic T cells, internal Mg2+ has been used as a tool to isolate the CRAC current from that of TRPM7 channels 41. To provide further evidence that TRPM7 might be involved in the generation of the Ca2+-sensing current, 8 mM MgCl2 was included in the pipette solution and the amplitude of the Ca2+-sensing current recorded with or without internal Mg2+ was compared. As shown in Fig. 2D-a, the presence of internal Mg2+ significantly inhibited the current in FaDu cells (n = 12 with [Mg2+]i and 6 without [Mg2+]i, p<0.05, two-way ANOVA), providing additional evidence that the Ca2+-sensing currents in FaDu cells are carried, at least partially, by TRPM7 channels.

Current-voltage relationship was then generated using a voltage ramp to see whether the Ca2+-sensing currents in FaDu cells show outward rectification in the presence of normal Ca2+, an important feature of the TRPM7 current. As shown in Fig. 2D-b, in the presence of normal Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the external solution, small inward currents were activated at negative potentials whereas larger outward currents were recorded at positive potentials, demonstrating a prominent outward rectification (n = 13). When the external solution was changed to divalent-free, the inward currents were dramatically increased resulting in a near linear I–V relationship (n = 10).

Taken together, both electrophysiological and pharmacological data strongly indicate an involvement of TRPM7 channels in mediating the Ca2+-sensing current in FaDu cells.

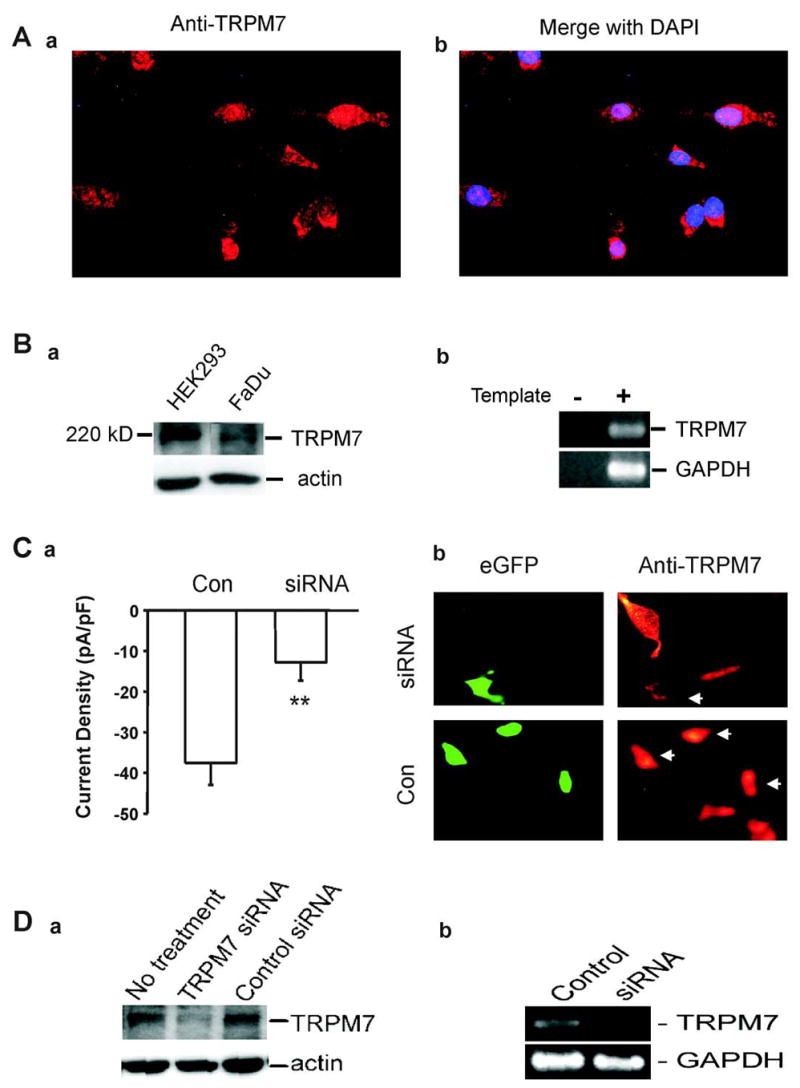

Detection of TRPM7 protein and mRNA in FaDu cells

We next decided to provide additional biochemical and molecular biological evidence to further demonstrate the existence of the TRPM7 channels in FaDu cells. We first employed immunocytochemistry to detect the existence of TRPM7 protein using TRPM7 antibody (Abgent, 1:100). As shown in Fig. 3A, clear immunoreactivity against TRPM7 was detected in almost all cells tested. Western blotting demonstrated a clear band with molecular weight of ~220kD (Fig. 3B-a). To verify the specificity of the antibody used, HEK293 cells stably transfected with TRPM7 16 was used as a positive control. As shown in Fig. 3B-a, following induction of TRPM7 expression, a clear protein band of ~220 kD was detected from the homogenate of HEK 293 cells. RT-PCR was also used to detect the presence of TRPM7 mRNA in FaDu cells. As shown in Fig. 3B-b, TRPM7 mRNA was present in FaDu cells.

Fig. 3. Detection of TRPM7 protein and mRNA in FaDu cells before and after siRNA-TRPM7 transfection.

A, Immunofluorescent image showing positive staining of FaDu cells with anti-TRPM7 antibody. Right panel shows overlaid image with anti-TRPM7 in red and DAPI-stained nuclei in blue. B. Detection of TRPM7 protein in FaDu cells by Western blot (a) and RT-PCR (b). For Western blot, HEK293 cells stably transfected with TRPM7 were served as a positive control, whereas actin was used as an internal control. For RT-PCR, ultra pure water was served as a negative control, whereas GAPDH was used as an internal control. C, a. Summary data showing the inhibition of the Ca2+-sensing currents in FaDu cells by TRPM7-siRNA. Currents were induced by a drop of [Ca2+]o from 2 mM to 0 mM at −60 mV with Mg2+-free pipette solution. Electrophysiological recordings were performed 72 hour following TRPM7-siRNA transfection. ** p<0.01. b, The specific loss of TRPM7 immunoreactivity was observed in cells transfected with TRPM7-siRNA as indicated by white arrows (upper panel), compared with no immunoreactivity changes when cells were transfected with empty vector (low panel). Left panel shows the cells with eGFP fluorescence as an indication of successful transfection. D, a. Western blotting images show the reduction of TRPM7 protein in FaDu cells transfected with TRPM7-siRNA compared with non-transfected or control-siRNA transfected cells. Actin was served as an internal control. b. RT-PCR images show reduction of TRPM7 mRNA in cells transfected with TRPM7-siRNA. Replacement of TRPM7 cDNA with ultra pure water was served as a negative control. GAPDH was used as an internal control.

Effects of TRPM7 siRNA-silencing on the Ca2+-sensing currents in FaDu cells

In order to obtain more evidence that TRPM7 channels are involved in mediating the Ca2+-sensing currents in FaDu cells, we employed RNA interference, a process of posttranscriptional gene silencing that inhibits the expression of native genes with high specificity 42,43. A 21-nucleotide siRNA duplex specifically targeting human TRPM7 was selected (see experimental procedures). In our experiments, about ~30% of FaDu cells were successfully transfected with siRNA as indicated by eGFP fluorescence.

To test the effect of TRPM7-siRNA on the Ca2+-sensing currents in FaDu cells, patch-clamp recording was performed on GFP-positive cells 72 h following TRPM7-siRNA transfection. As shown in Fig. 3C-a, the amplitude of the Ca2+-sensing current was significantly reduced in FaDu cells transfected with TRPM7-siRNA. In 6 cells tested, the current density was decreased by 65.45 ± 26.72% in cells transfected with TRPM-siRNA, as compared with the control cells trasfected with the empty vector.

Immunocytochemistry and Western blot were used to confirm the reduction of TRPM7 protein by TRPM7-siRNA. As shown in Fig. 3C-b, in siRNA transfected cells (as indicated by eGFP), the specific loss of TRPM7 immunoreactivity was observed, whereas in cells transfected with vector alone strong immunoreactivity against TRPM7 exists. Consistent with the images acquired from immunocytochemistry, Western blotting showed a significant reduction in the density of 220kD band in TRPM7-siRNA transfected cells (Fig. 3D-a).

RT-PCR was further employed to see whether transfection with TRPM7-siRNA suppresses the expression of TRPM7 mRNA in FaDu cells. As shown in Fig. 3D-b, transfection of FaDu cells with TRPM7-siRNA induced an apparent suppression of TRPM7 mRNA 72h after the transfection, whereas transfection with vector alone had no effect.

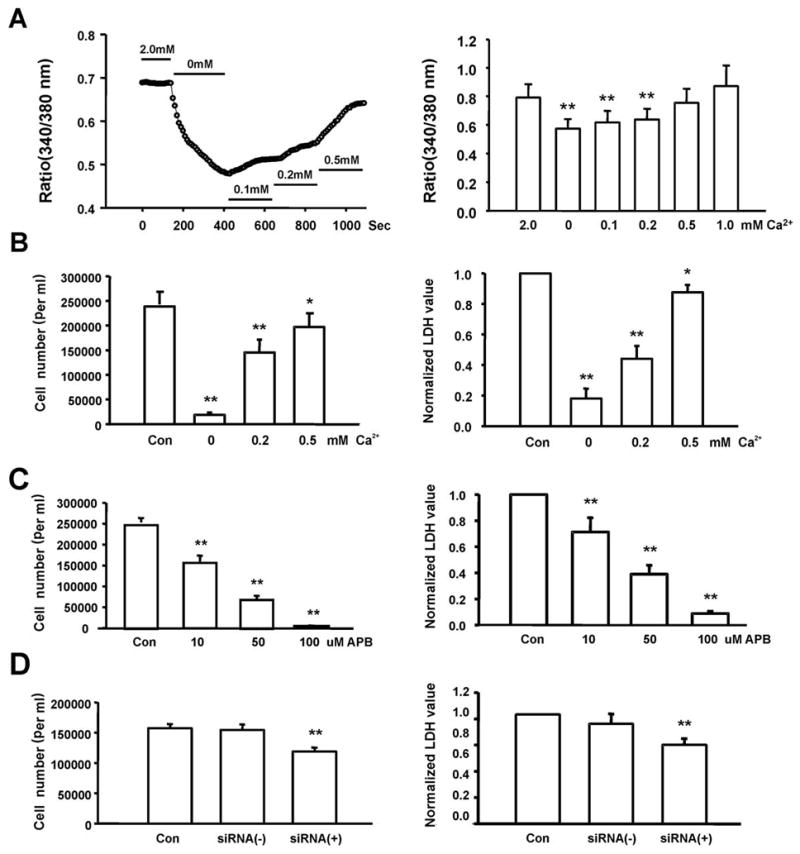

Ca2+ is critical to FaDu cell growth

Ca2+ signaling is fundamental for cell cycling and proliferation. The increase of cellular Ca2+ requires either Ca2+ release from intracellular stores or Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space. Given the fact that TRPM7 channel is Ca2+-permeable and activation of these channels is expected to affect the concentration of intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i), we performed Ca2+-imaging experiments to monitor changes of [Ca2+]i in response to changes of [Ca2+]o. In a total of 73 cells tested, 34 cells (~47%) responded to changes of [Ca2+]o with detectable changes of [Ca2+]i. As shown in Fig. 4A, over a range of 0 to 2 mM [Ca2+]o, [Ca2+]i changes in parallel to the changes of [Ca2+]o. Since changing [Ca2+]o affects the driving force for Ca2+ entering the cells, this data suggests that there might be a basal activation of TRPM7 channels.

Fig. 4. Ca2+ and TRPM7 are critical to FaDu cell growth and proliferation.

A, Fura-2 fluorescent imaging showing changes of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration as indicated by 340/380 nm ratio in response to changes in [Ca2+]o (left panel), and summary data showing changes of [Ca2+]i as indicated by 340/380 nm ratio in response to changes in [Ca2+]o (right panel, n = 5–9, **p<0.01 compared to 2.0 mM [Ca2+]o). B, Effect of [Ca2+]o on the growth and proliferation of FaDu cells as measured by direct cell counting (left) or total LDH release (right). Over a range of [Ca2+]o from 1 mM to 0.1 mM, the rate of proliferation of the FaDu cells decreased in parallel with decreasing [Ca2+]o. For each data point, 16–32 wells of cells from 4–8 independent experiments were analyzed. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 compared to 2.0 mM [Ca2+]o. C, Concentration-dependent inhibition of the proliferation of FaDu cells by 2-APB, measured by cell count (left) or total LDH release (right). D. Inhibition of the proliferation of FaDu cells by TRPM7-siRNA, evaluated by cell count (left) and LDH assay (right). Control - cells grew in normal medium, siRNA (+) - cells were transfected with TRPM7-siRNA, siRNA (−) - cells were transfected with negative siRNA. For each data point, 16–32 wells of cells from 4–8 independent experiments were analyzed. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01.

We next examined whether a change in [Ca2+]o affects the growth and proliferation of FaDu cells. As shown in Fig. 4B, the degree of proliferation of FaDu cells is closely regulated by the concentration of the [Ca2+]o (Fig. 4B, left panel). In a range between 1 mM and 0.1 mM [Ca2+]o, the rate of proliferation of FaDu cells decreased gradually with a parallel reduction in [Ca2+]o.

In addition to cell counting, we employed the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay to acquire more objective data on cell proliferation. LDH is a ubiquitous enzyme in all living cells, and the total amount of LDH releasable is proportional to the number of cells tested 44. 72h following the culturing of FaDu cells in medium with different concentrations of [Ca2+]o, total amount of releasable LDH in each well was measured by permeabilizing the cells with 0.5% Triton X-100. As shown in Fig. 4B (right panel), LDH measurement also demonstrated a clear dependence of the proliferation of FaDu cells on [Ca2+]o.

Inhibition of FaDu cell proliferation by pharmacological blockade of TRPM7 or suppression of TRPM7 protein expression

Since Ca2+ is critical to FaDu cell growth, and that TRPM7 is an excellent candidate of numerous Ca2+-dependent cell processes in non-excitable cells, we sought to determine whether the activities of TRPM7 channels indeed influence the growth and proliferation of FaDu cells. First, we tested the effect of Gd3+, a non-specific TRPM7 channel inhibitor, on the proliferation of FaDu cells. Addition of 50 μM and 100 μM Gd3+ in the culture medium inhibited the growth of FaDu cells by 18.29 ± 2.59% (p<0.01) and 39.44 ± 7.20% (p<0.01) with cell counting (n = 16 wells), and 36.99 ± 7.28% (p<0.01) and 50.37 ± 7.80% (p<0.01) with LDH assay (n = 16 wells, not shown). Similar to Gd3+, 2-APB also inhibited the proliferation of FaDu cells (Fig. 4C).

TRPM7-siRNA was then employed to selectively suppress the expression of TRPM7 channels. As shown in Fig. 4D, transfection of cells with 30 nM TRPM7-siRNA significantly inhibited FaDu cell proliferation as indicated by reduced cell counting and total LDH release. The moderate reduction in cell growth by TRPM7-siRNA is likely due to the low transfection efficiency (~30%). Cells transfected with negative control siRNA showed no difference in cell proliferation compared with non-transfected cells. Taken together, our data strongly suggest that activation of TRPM7 channels and increases of [Ca2+]i play an important role in the growth and proliferation of FaDu cells.

TRPM7-like current in SCC25 cell lines

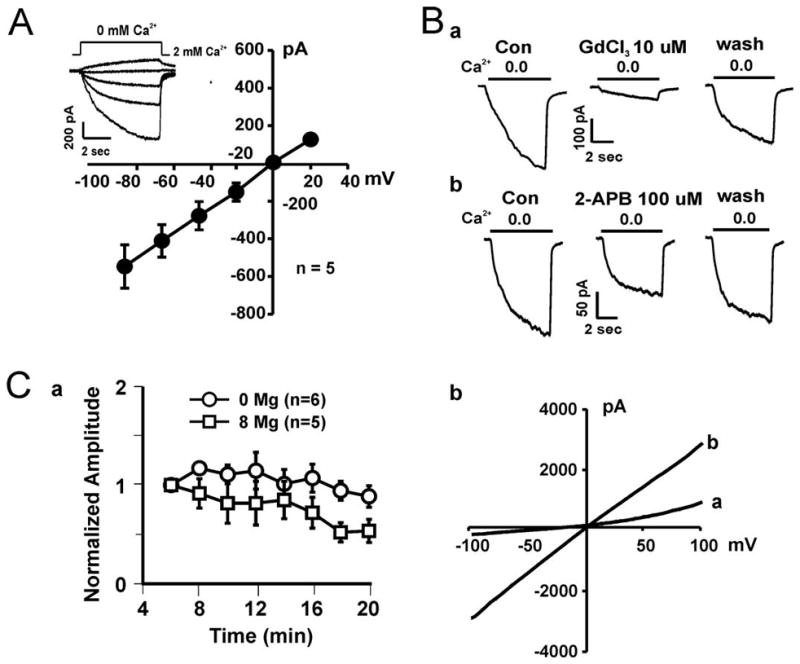

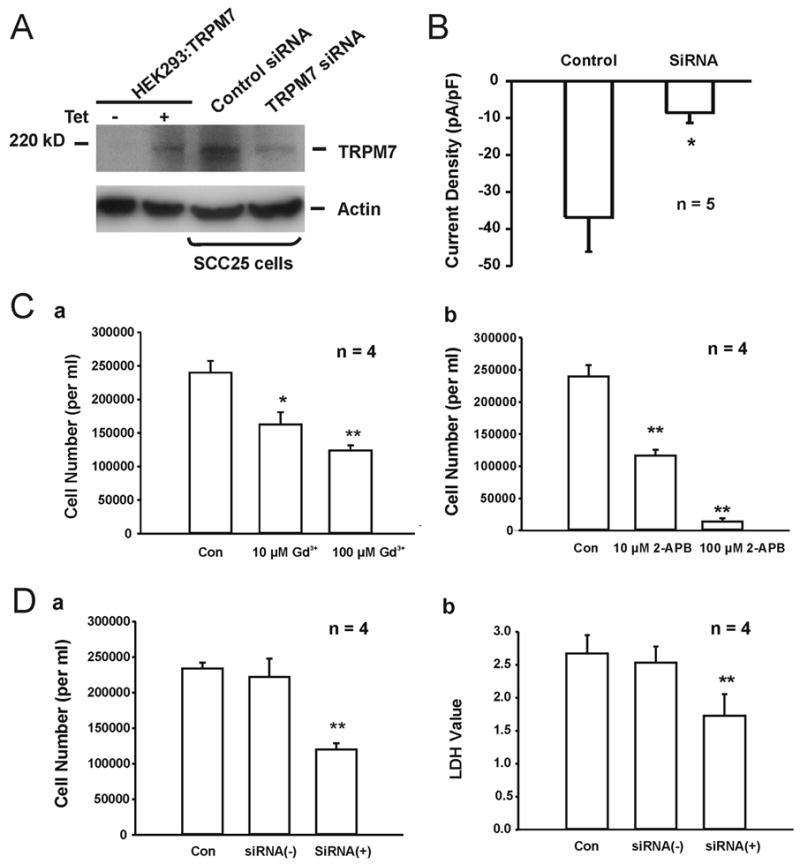

To provide additional evidence that TRPM7 like channels play an important role in the growth and prolifereation of human head and neck tumor cells, we have performed similar experiments in SCC25 cells, a common cell line of human thyroid squamous cell carcinoma. Similar to FaDu cells, lowering extracelllular Ca2+ activated large inward current (Fig. 5A, inset). The amplitude of the inward current decreases with membrane depolarization resulting in a linear current-voltage relationship and a reversal potential of ~0 mV (Fig. 5A, n = 5). Addition of 10 μM Gd3+ dramatically decreased the low Ca2+ activated current by ~70% (from 535.7 ± 99.3 pA to 113.8 ± 87.7 pA, n = 4, p<0.05, Fig. 5B-a). Addition of 100 μM 2-APB also inhibited the current by more than 30% (from 521.3 ± 90.4 pA to 378.9 ± 90.9 pA, n = 5, p<0.05, Fig. 5B-b). Inclusion of high concentration of Mg2+ in the intracellular solution gradually suppressed the current. When normalized to the current amplitude recorded 5 min after establishing the whole-cell configuration, the relative amplitude of the Ca2+-sensing current at 20 min was 0.89 ± 0.11 for 0 mM intracellular Mg2+ but 0.54 ± 0.12 for 8 mM intracellular Mg2+ (Fig. 5C-a, n = 5–6, p<0.01). Similar to the finding in FaDu cells, current-voltage relationship in SCC25 cells showed outward rectification in the presence of normal Ca2+, but became linear in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 5C-b, n = 4). Together, both electrophysiological and pharmacological data strongly support the existence of TRPM7 channels in SCC25 cells. Like in FaDu cells, Western blot detected a protein band of ~220 kD in SCC25 cells (Fig. 6A). To provide more evidence that TRPM7 channels are indeed involved in mediating the Ca2+-sensing currents in SCC25 cells, siRNA-TRPM7 was used to reduce the expression of TRPM7 channels as described above (Fig. 6A). Patch-clamp recording was performed on GFP-positive cells 72 h following TRPM7-siRNA transfection. As shown in Fig. 6B, the amplitude of the Ca2+-sensing current was significantly reduced in SCC25 cells transfected with TRPM7-siRNA. The current density was reduced from 37.2 ± 2.3 pA/pF in control cells trasfected with the empty vector to 8.7 ± 2.8 pA/pF in cells transfected with TRPM-siRNA (n = 5 in each group, p<0.05). Finally, the potential role of TRPM7 in the growth and prolifereation of the SCC25 cells was evaluated by examining the effect of Gd3+, 2-APB, and siRNA-TRPM on the changes of cell count or LDH release 72h after incubation with those agents. As shown in Fig. 6C–D, addition of Gd3+, 2-APB, or si-RNA all inhibited the growth and proliferation of the SCC25 cells.

Fig. 5. Electrophysiological and pharmacological characterization of the Ca2+-sensitive currents in SCC25 cells.

A, Left panel: Representative traces (inset) and summary I–V relationship showing the Ca2+-sensitive current recorded at different holding potentials. A rapid drop of [Ca2+]o from 2 mM to 0 mM (nominally free) evoked slow non-desensitizing currents that rapidly recovered upon restoration of [Ca2+]o. B, Representative traces showing inhibition of the Ca2+-sensitive current in SCC25 cells by 10 μM Gd3+ and 2-APB. Addition of 10 μM Gd3+ reduced the amplitude of the inward current from 535.7 ± 99.3 pA to 113.8 ± 87.7 pA (n = 4, p<0.05), whereas addition of 10 μM 2-APB inhibited the current from 521.3 ± 90.4 pA to 378.9 ± 90.9 pA (n = 5, p<0.05). C, a. Summary data showing the time-dependent inhibition of the Ca2+-sensitive current by intracellular Mg2+. The amplitude of the peak inward current activated at −60 mV was normalized to that recorded 5 min after the formation of whole-cell configuration (n = 5 & 6). The relative amplitude of the peak inward current at 20 min was 0.89 ± 0.11 and 0.54 ± 0.12 for current recorded in the absence of intracellular Mg2+ and in the presence of 8 mM Mg2+, respectively (p < 0.01). b. Representative I–V curve generated by depolarizing ramp pulses in the presence (a) or absence (b) of 2 mM extracellular Ca2+. An outward rectification is apparent in the presence of 2 mM Ca2+ (trace a).

Fig. 6. Inhibition of the growth and proliferation of SCC25 cells by pharmacological blockade of TRPM7-like current or suppression of TRPM7 expression.

A, Western blotting images showing the detection of TRPM7 protein in SCC25 before and after TRPM7 siRNA transfection. HEK293 cells with induced expression of TRPM7 channels was used as positive control, and actin was served as an internal control. B, Summary data showing the reduction of TRPM7-like current in SCC25 cells 72h after transfection with TRPM7 siRNA. C, a. Concentration-dependent inhibition of the proliferation of SCC25 cells by Gd3+, measured by cell count. b. Concentration-dependent inhibition of the proliferation of SCC25 cells by 2-APB, measured by cell count. D, Inhibition of the proliferation of SCC25 cells by TRPM7-siRNA, evaluated by cell count (a) and LDH assay (b). Control - cells grew in normal medium, siRNA (+) - cells were transfected with TRPM7-siRNA, siRNA (−) - cells were transfected with negative control siRNA. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01.

Discussion

It has long been known that ion channels are of great importance for a large variety of physiological functions, including electrical signaling, gene expression, control of muscle contraction, cell volume regulation, and hormone secretion etc. In contrast to these beneficial effects, certain channel proteins have been proposed to promote the growth and proliferation of tumor cells 45–47. It is suggested that, during the change from a normal cell towards cancer, a series of genetic alterations take place, which may affect the expression of ion channels or induce changes in channel property/activity. The abnormal ion channel property/activity is then able to promote the growth and proliferation of the tumor 46. Melastatin, for example, function as a tumor suppressor which is down-regulated in highly metastatic cells. For this reason, assessment of melastatin mRNA in primary cutaneous tumors has been used as a prognostic marker for metastasis in patients with localized malignant melanoma 48,49. Similarly, TRPM8 channel protein has been used as a prostate-specific marker; TRPM8 levels decrease with tumor progression, and the loss of TRPM8 is considered as a sign of a poor prognosis 50,51. In addition, TRPV6 expression has been considered a prognostic marker and a promising target for new therapeutic strategies for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer 52. Therefore, the pathophysiological function of ion channels is one of the interesting new research areas, which may offer alternative prognostic and therapeutic strategies for cancer patients. In line with this argument, our studies demonstrated the presence of TRPM7 channels in human head and neck tumor cell lines, and that activation of these channels likely influences the growth and proliferation of these cells.

We first demonstrated the presence of a Ca2+-sensing current in FaDu and FCC25 cells, two common cell lines of human head and neck tumor. Several lines of evidence indicate that this Ca2+-sensing current is carried, at least partially, by TRPM7 channels. (1) The current is modulated by [Ca2+]o, with increased amplitude recorded in low Ca2+ external solutions. This feature is similar to TRPM7 currents recorded in other cells and in heterologous expression systems 15,16,25,41. (2) The current is voltage-independent with a reversal potential around 0 mV and a strong outward rectification in the presence of normal [Ca2+]o, consistent with the characteristics of TRPM7 channels which are non-selective for cations and show significant outward rectification 15,16. (3) Inhibition of the Ca2+-sensing current by 2-APB, a non-specific TRPM7 blocker, along with its sensitivity to Gd3+, also suggests the involvement of TRPM7 channels 16,32,41. (4) Inhibition of this current by intracellular Mg2+ is another important feature of TRPM7 channels 15,32,40,41. (5) Reduction of the current by TRPM7-siRNA further supports an involvement of TRPM7 channels in mediating the Ca2+-sensing current in FaDu and SCC25 cells. (6) Finally, Western blot and RT-PCR detected the presence of TRPM7 protein and mRNA in these cells.

CRAC channels share some electrophysiological feature with TRPM7 channels 32,41,53. For example, both channels are Ca2+-permeable, inhibited by Gd3+, and conduct monovalent cations when external divalent cations are omitted. However, at physiological [Ca2+]o and [Na+]o, the reversal potential for TRPM7 current is ~0 mV, whereas it is >40 mV for CRAC current 53. Moreover, TRPM7 channels have a much larger single-channel conductance (40 pS versus < 1 pS for CRAC), and the whole-cell currents demonstrate a strong outward rectification in contrast to inward rectification for CRAC current.

The exact mechanism for TRPM7 activation/modulation is still unclear. An early study 54 suggested that receptor-mediated breakdown of phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2) mediates negative-feedback inhibition of TRPM7, whereas a different study suggested that TRPM7 is regulated either positively or negatively by changes in the level of intracellular cAMP 55. Our recent studies suggested that oxygen free radicals generated during anoxia may directly activate the TRPM7 channels 16. Jiang and colleagues also demonstrated that in TRPM7-transfected HEK-293 cells and in rat basophilic leukemia cells, TRPM7 current could be potentiated by a decrease in pHo 56. It is thus likely that under pathological conditions such as various forms of injury, infection, inflammation, and tumor progression, TRPM7 may become activated by combined oxidative stress and acidosis. Our findings that pharmacological inhibition of TRPM7 channels or knock down the expression of TRPM7 mRNA suppress the growth and proliferation of FaDu and SCC25 cells indicate an important role of these channels in the growth and proliferation of malignant head and neck tumor cells.

Tumor cells may exhibit a lower extracellular pH (6.5 – 6.9) than normal tissues (7.0–7.5)57,58. Given the fact that over-growth of many tumor cells is also associated with hypoxia in their micro-environment, one would expect that TRPM7 currents in tumor cells may be activated due to the oxidative stress 16, and potentiated by the pathological acidic conditions 56. In the present study, we did not examine the possible consequence of acid potentiation of TRPM7-like current on the proliferation of FaDu cells. Future studies will mimic the in vivo micro-environment of tumor cells in which both acid accumulation and hypoxia will be implemented.

There is a lack of close correlation with doses used for Gd3+ and 2-APB to inhibit Ca2+ sensitive inward current, and those used to prevent cell growth. For Gd3+, higher concentration is required for inhibiting the cell growth than the inward current, whereas it is the opposite for 2-APB. It is likely due the non-specificity of these blockers. As mentioned above, over a concentration range of 10 – 100 μM, 2-APB has broad inhibitory effects on TRP superfamily of ion channels including TRPM7. It may be possible that other TRP channels exist and partially contribute to the growth of FaDu and SCC25 cells. In addition to inhibiting TRPM7, Gd3+ is known to affect the activities of other ion channel/receptor. For example, it is an agonist for the Ca2+-sensing receptor 59. Activation of Ca2+-sensing receptors is known to induce intracellular Ca2+ release, which may stimulate the cell growth and counteract its inhibition of TRPM7-mediated cell growth. Future studies will determine whether FaDu and SCC25 cells express other TRP channels and Ca2+-sensing receptors. Nevertheless, the lack of close correction between the inhibition of inward current and the rate of cell growth by Gd3+ and 2-APB should not reject the claim that TRPM7 is involved in the growth and proliferation of these cells since our conclusion was based the effects of Gd3+, 2-APB, and siRNA-TRPM7 all together.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jingquan Lan, Theresa Lusardi for technical assistance, and Eric M. Kratzer for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01NS049470 and R01NS42926 to ZGX).

References

- 1.Parekh AB, Penner R. Store depletion and calcium influx. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:901–30. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berridge MJ. Capacitative calcium entry. Biochem J. 1995;312:1–11. doi: 10.1042/bj3120001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas AP, Bird GS, Hajnoczky G, Robb-Gaspers LD, Putney JW., Jr Spatial and temporal aspects of cellular calcium signaling. FASEB J. 1996;10:1505–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clapham DE. TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature. 2003;426:517–24. doi: 10.1038/nature02196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleig A, Penner R. The TRPM ion channel subfamily: molecular, biophysical and functional features. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:633–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsey IS, Delling M, Clapham DE. An introduction to TRP channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:619–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040204.100431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minke B. TRP channels and Ca2+ signaling. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:261–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Lipp P. Calcium - a life and death signal. Nature. 1998;395:645–48. doi: 10.1038/27094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Means AR. Calcium, calmodulin and cell cycle regulation. FEBS Lett. 1994;347:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00492-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoth M, Penner R. Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates a calcium current in mast cells. Nature. 1992;355:353–56. doi: 10.1038/355353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakowski D, Parekh AB. Permeation through store-operated CRAC channels in divalent-free solution: potential problems and implications for putative CRAC channel genes. Cell Calcium. 2002;32:379–91. doi: 10.1016/s0143416002001914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prakriya M, Lewis RS. CRAC channels: activation, permeation, and the search for a molecular identity. Cell Calcium. 2003;33:311–21. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanano T, Hara Y, Shi J, et al. Involvement of TRPM7 in cell growth as a spontaneously activated Ca2+ entry pathway in human retinoblastoma cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;95:403–19. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0040273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmitz C, Perraud AL, Johnson CO, et al. Regulation of vertebrate cellular Mg2+ homeostasis by TRPM7. Cell. 2003;114:191–200. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00556-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nadler MJ, Hermosura MC, Inabe K, et al. LTRPC7 is a Mg. ATP-regulated divalent cation channel required for cell viability. Nature. 2001;411:590–95. doi: 10.1038/35079092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aarts M, Iihara K, Wei WL, et al. A key role for TRPM7 channels in anoxic neuronal death. Cell. 2003;115:863–77. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiong ZG, Zhu XM, Chu XP, et al. Neuroprotection in ischemia: blocking calcium-permeable acid-sensing ion channels. Cell. 2004;118:687–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henshall DC, Araki T, Schindler CK, Shinoda S, Lan JQ, Simon RP. Expression of death-associated protein kinase and recruitment to the tumor necrosis factor signaling pathway following brief seizures. J Neurochem. 2003;86:1260–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meller R, Schindler CK, Chu XP, et al. Seizure-like activity leads to the release of BAD from 14-3-3 protein and cell death in hippocampal neurons in vitro. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:539–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108:193–99. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rangan SR. A new human cell line (FaDu) from a hypopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 1972;29:117–21. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197201)29:1<117::aid-cncr2820290119>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faust JB, Meeker TC. Amplification and expression of the bcl-1 gene in human solid tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1992;52:2460–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong ZG, Chu XP, Simon RP. Ca2+ -permeable acid-sensing ion channels and ischemic brain injury. J Membr Biol. 2006;209:659–86. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0840-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aarts MM, Tymianski M. TRPMs and neuronal cell death. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:243–249. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang X, Newell EW, chlichter LC. Regulation of a TRPM7-like current in rat brain microglia. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42867–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304487200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Epithelial Ca2+ and Mg2+ channels in health and disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:15–26. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gwanyanya A, Sipido KR, Vereecke J, Mubagwa K. ATP and PIP2 dependence of the magnesium-inhibited, TRPM7-like cation channel in cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C627–35. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00074.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He Y, Yao G, Savoia C, Touyz RM. Transient receptor potential melastatin 7 ion channels regulate magnesium homeostasis in vascular smooth muscle cells: role of angiotensin II. Circ Res. 2005;96:207–15. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000152967.88472.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiong Z, Lu W, MacDonald JF. Extracellular calcium sensed by a novel cation channel in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7012–17. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.7012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X, Groschner K, Ambudkar IS. Distinct Ca2+-permeable cation currents are activated by internal Ca2+-store depletion in RBL-2H3 cells and human salivary gland cells, HSG and HSY. J Membr Biol. 2004;200:93–104. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0698-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monteilh-Zoller MK, Hermosura MC, Nadler MJ, Scharenberg AM, Penner R, Fleig A. TRPM7 provides an ion channel mechanism for cellular entry of trace metal ions. J Gen Physiol. 2003;121:49–60. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hermosura MC, Monteilh-Zoller MK, Scharenberg AM, Penner R, Fleig A. Dissociation of the store-operated calcium current I(CRAC) and the Mg-nucleotide-regulated metal ion current MagNuM. J Physiol. 2002;539:445–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu SZ, Zeng F, Boulay G, Grimm C, Harteneck C, Beech DJ. Block of TRPC5 channels by 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate: a differential, extracellular and voltage-dependent effect. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;145:405–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma HT, Patterson RL, van Rossum DB, Birnbaumer L, Mikoshiba K, Gill DL. Requirement of the inositol trisphosphate receptor for activation of store-operated Ca2+ channels. Science. 2000;287:1647–51. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schindl R, Kahr H, Graz I, Groschner K, Romanin C. Store depletion-activated CaT1 currents in rat basophilic leukemia mast cells are inhibited by 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate. Evidence for a regulatory component that controls activation of both CaT1 and CRAC (Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel) channels. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26950–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203700200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trebak M, Bird GS, McKay RR, Putney JW., Jr Comparison of human TRPC3 channels in receptor-activated and store-operated modes. Differential sensitivity to channel blockers suggests fundamental differences in channel composition. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21617–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202549200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiong ZG, MacDonald JF. Sensing of extracellular calcium by neurones. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1999;77:715–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernardini G, Peracchia C, Peracchia LL. Reversible effects of heptanol on gap junction structure and cell-to-cell electrical coupling. Eur J Cell Biol. 1984;34:307–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takens-Kwak BR, Jongsma HJ, Rook MB, Van Ginneken AC. Mechanism of heptanol-induced uncoupling of cardiac gap junctions: a perforated patch-clamp study. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C1531–38. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.6.C1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kozak JA, Cahalan MD. MIC channels are inhibited by internal divalent cations but not ATP. Biophys J. 2003;84:922–27. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74909-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prakriya M, Lewis RS. Separation and characterization of currents through store-operated CRAC channels and Mg2+-inhibited cation (MIC) channels. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119:487–507. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 2001;411:494–98. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cullen BR. RNA interference: antiviral defense and genetic tool. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:597–99. doi: 10.1038/ni0702-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koh JY, Choi DW. Quantitative determination of glutamate mediated cortical neuronal injury in cell culture by lactate dehydrogenase efflux assay. J Neurosci Methods. 1987;20:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(87)90041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pardo LA, Contreras-Jurado C, Zientkowska M, Alves F, Stuhmer W. Role of voltage-gated potassium channels in cancer. J Membr Biol. 2005;205:115–24. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0776-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kunzelmann K. Ion channels and cancer. J Membr Biol. 2005;205:159–73. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0781-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bodding M. TRP proteins and cancer. Cell Signal. 2007;19:617–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duncan LM, Deeds J, Hunter J, et al. Down-regulation of the novel gene melastatin correlates with potential for melanoma metastasis. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1515–0. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duncan LM, Deeds J, Cronin FE, et al. Melastatin expression and prognosis in cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:568–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsavaler L, Shapero MH, Morkowski S, Laus R. Trp-p8, a novel prostate-specific gene, is up-regulated in prostate cancer and other malignancies and shares high homology with transient receptor potential calcium channel proteins. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3760–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Henshall SM, Afar DE, Hiller J, et al. Survival analysis of genome-wide gene expression profiles of prostate cancers identifies new prognostic targets of disease relapse. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4196–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fixemer T, Wissenbach U, Flockerzi V, Bonkhoff H. Expression of the Ca2+-selective cation channel TRPV6 in human prostate cancer: a novel prognostic marker for tumor progression. Oncogene. 2003;22:7858–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kozak JA, Kerschbaum HH, Cahalan MD. Distinct properties of CRAC and MIC channels in RBL cells. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:221–35. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Runnels LW, Yue L, Clapham DE. The TRPM7 channel is inactivated by PIP2 hydrolysis. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:329–36. doi: 10.1038/ncb781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takezawa R, Schmitz C, Demeuse P, Scharenberg AM, Penner R, Fleig A. Receptor-mediated regulation of the TRPM7 channel through its endogenous protein kinase domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6009–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307565101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiang J, Li M, Yue L. Potentiation of TRPM7 inward currents by protons. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:137–50. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gerweck LE, Seetharaman K. Cellular pH gradient in tumor versus normal tissue: potential exploitation for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1194–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vaupel P, Kallinowski F, Okunieff P. Blood flow, oxygen and nutrient supply, and metabolic microenvironment of human tumors: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6449–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Quinn SJ, Ye CP, Diaz R, et al. The Ca2+-sensing receptor: a target for polyamines. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1315–23. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]