Abstract

The intronic Eμ enhancer has been implicated in immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) locus transcription, VDJ recombination, class switch recombination (CSR)2 and somatic hypermutation (SHM). How Eμ controls these diverse mechanisms is still largely unclear, but transcriptional enhancer activity is thought to play a central role. Here we compare the phenotype of mice lacking the Eμ element (ΔEμ) with that of mice in which Eμ was replaced with the ubiquitous SV40 transcriptional enhancer (SV40eR mutation), and show that SV40e cannot functionally complement Eμ loss in pro-B cells. Surprisingly, in fact, the SV40eR mutation yields a more profound defect than ΔEμ, with an almost complete block in μ0 germline transcription in pro-B cells. This active transcriptional suppression caused by enhancer replacement appears to be specific to the early stages of B cell development, as mature SV40eR B cells express μ0 transcripts at higher levels than ΔEμ mice, and undergo complete DNA demethylation at the IgH locus. These results indicate an unexpectedly stringent, developmentally-restricted requirement for enhancer specificity in regulating IgH function during the early phases of B cell differentiation, consistent with the view that coordination of multiple independent regulatory mechanisms and elements is essential for locus activation and VDJ recombination.

Keywords: Antibodies, Gene regulation, Gene rearrangement, Transgenic/knockout mice

Introduction

The immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) locus intronic enhancer, Eμ, was one of the first transcriptional enhancers identified, and remains one of the best characterized (reviewed in (1). It is organized around a central core element (cEμ) flanked by two matrix attachment regions (MARs) (reviewed in 1). In addition to its activity as a transcriptional regulator, Eμ has been implicated in VDJ recombination and class switch recombination (CSR) (2–7). An involvement of Eμ in somatic hypermutation (SHM) has also been proposed, although clear-cut evidence for this effect is still lacking (7, 8). A critical outstanding question regarding Eμ’s multifaceted activities is how a single regulatory element, albeit complex like Eμ, can be implicated in such a diverse array of mechanisms. In particular, we are interested in understanding whether Eμ multifunctionality reflects inherent functional sub-specialization of individual enhancer elements, or whether a common functional principle underlies the regulatory processes for all mechanisms.

The regulated process of V(D)J recombination requires the sequential activation of variable (V), diversity (D) and joining (J) segments in antigen receptor gene loci at specific developmental stages (9, 10). The precise mechanisms that determine this step-wise regulation are being actively investigated, but in agreement with the “accessibility model”, they seem to be linked to transcriptional activation and/or concomitant alterations in DNA methylation and histone remodeling at the targeted regions (9–11).

The role of cis-acting regulatory elements in V(D)J recombination at the various Ig and TCR loci has been studied primarily using artificial recombination constructs in cell lines and transgenics, as well as in gene-targeting models (reviewed in 10, 12–14). In the case of Eμ, these experiments have conclusively shown that this element, although not absolutely required for IgH locus rearrangement, is necessary for efficient D-J and V-DJ recombination steps, the bulk of this activity being attributable to the core Eμ element rather than the flanking MARs (2, 3, 5, 7, 15). An additional IgH regulatory element, which drives transcription of DQ52, the most Eμ-proximal DH segment, was shown to be dispensable for initiation of D-JH recombination (15). Finally, Eμ has also been shown to play similarly non-necessary but important roles in CSR, and in the case of SHM, in artificial constructs and cell lines but not the targeted endogenous IgH locus (4, 6–8, 16, 17).

The requirement for transcription in VDJ recombination, CSR and SHM raises the possibility of a direct relationship between Eμ’s enhancer activity and these processes. Indeed, Eμ activity in artificial transgenic substrates for all three processes can be replaced by other transcriptional regulatory elements, including non-specific enhancers (17–22). Similarly, the replacement of enhancer elements for other antigen receptor loci (Ig light chains or T cell receptor loci) with exogenous enhancer elements results in changes in timing and lineage specificity of VDJ rearrangement, but limited decrease in overall activity (23, 24).

Thus, Eμ’s diverse functions in IgH locus regulation could indirectly be attributed entirely to its activity as a transcriptional enhancer. To address this question, we generated mice bearing either a complete deletion of the Eμ core enhancer element, or replacing it with the strong, ubiquitous SV40 enhancer, and compared their B cell phenotypes.

Materials and methods

Generation of targeted embryonic stem cell clones and mutant mice

ΔEμ and SV40eR vectors were generated by replacing the 272-bp SspI-PpuMI fragment spanning the IgH Eμ core enhancer region with a LoxP-flanked pgk-neor gene (deletion) or with 275 bp SV40 core enhancer sequence plus LoxP-flanked pgk-neor gene (replacement). The two flanking arms were a 6.2 kb EcoRI-SspI fragment at the 5′, and a 1.6 kb PpuMI-HindIII fragment at the 3′. A thymidine kinase gene driven by pgk promoter was inserted at the 3′ end of the construct for double G418/gancyclovir selection of homologous recombinants. F1.11 IgHa/b heterozygous ES cells (a gift from Barry Sleckman, Washington University, St. Louis, MO) were transfected by electroporation. Double G418/gancylovir resistant clones were screened for homologous recombination by Southern blotting using a 0.8 kb XbaI-BamHI fragment 5′ of the Cμ gene as a probe. Positive clones were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts, and resulting chimeric mice were first bred for germline transmission with C57BL/6 mice. Heterozygous progeny carrying mutated IgH allele were identified by PCR using primers PGK-F and Smu-B, (Table I), and bred with transgenic mice bearing a Cre recombinase gene driven by the adenovirus EIIA promoter (25) for LoxP-mediated deletion of the pgk-neor gene. Mice in which the neo gene had been deleted were identified by genomic DNA PCR using primers UDEμ-F and UDEμ-B (Table I). For analysis of IgH locus expression in pro-B cells, ΔEμ and SV40eR mice were bred with RAG2-deficient mice (26). All experiments involving mice were conducted in accordance with local and federal guidelines for the humane treatment of experimental animals, following protocols approved by the University of Rochester Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Table I.

List of PCR primers and oligo probes

| Name | 5′-3′ sequence | Temp. | PCR product size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primers used to screen mice for germline transmission and neo-gene deletion | |||

| PGK-F

Smu-B |

GGGGTGGGGGTGGGATTAGATA

GGCCCAGCTCATTCCAGTTCATTA |

60°C | 2 kb |

| UDEμ-F

UDEμ-B |

TTAAGGGAGGAATGGGAGTGA

AAGGTAAAATTAAAAGGTTGAA |

50°C | 393 bp (wt)

503 bp (SV40eR) 283 bp (Δ) |

| RT-PCR primers | |||

| Mu0

GLμR |

CCGCATGCCAAGGCTAGCCTGAAAGATTACC

GGTACTTGCCCCCTGTCCTCA |

58°C | 570 bp |

| CμAH-F

CμAH-B |

TCCCAAATGTCTTCCCCCTCGTC

GAAGTTCGTGGCCTCGCAGATG |

59°C | 519 bp |

| VHJ558Sc

GLμR |

CGAGCTCTCCARCACAGCCTWCATGCARCTCARC

GGTACTTGCCCCCTGTCCTCA |

58°C | 330 bp |

| VHJ558

J558Sp2 |

GCGAAGCTTARGCCTGGGRCTTCAGTGAAG

GACACACTCAGGATGTGGTTACAA |

58°C | 294 bp |

| Mb1 F

Mb1 B |

GCCAGGGGGTCTAGAAGC

TCACTTGGCACCCAGTACAA |

55°C | 308 bp |

| λ5-F

λ5-B |

TTGGGTCTAGTGGATGGTGTCC

CTGACCTAGGATTGTGAGCTGGGT |

58°C | 250 bp |

| RT-HPRT

HPRT-F HPRT-B |

CTCTTAGATGCTGTTACTGATAGG

GTTGGATACAGGCCAGACTTTGTTG GAGGGTAGGCTGGCCTATAGGCT |

55°C | RT primer

352 bp |

| 7183As

VH7183Sc 7183S |

GATGCTCTGCAGGAGGTTTT

CGGTACCAAGAASAMCCTGTWCCTGCAAATGASC GAGCTCACAGTAACTTTTGCT |

55°C | RT primer

100 bp |

| Quantitative real-time PCR primers | |||

| Mu0 qPCR F

Mu0 qPCR B |

TGCAGGTTCCTCTCTCGTTTCCTT

TGGGCCCATCTGTAGGATGGTAAT |

61°C | 115 bp |

| Mb1 qPCR F

Mb1 qPCR B |

AATGAGCCCTTAATCGCTGCCTCT

CAAGGGCTGCTTTGGGAAGGATTT |

60°C | 124 bp |

| Primers used to generate probes and oligo-probe | |||

| VHJ558Sc | CGAGCTCTCCARCACAGCCTWCATGCARCTCARC | ||

| UpJH1-F

UpJH1-B |

CAGGAGACAGTGCAGAGAAGAACG

GCCCCCTGGTCCTAGCACATCA |

58°C | 443 bp |

| AIDexon3

AID-B |

TGTTACCGCGTCACCTG

AGAGAAATTTCATCACGTGTGACATT |

55°C | 414 bp |

| Chr2–55 –F

Chr2–55 -B |

CCTCCCTGAAACCCCCTATCC

TTTTGGCCTGTTCTAACCTTCCTG |

58°C | 2 kb |

| DQ52 3′ F

JH1 5′ Rev |

GACGCGTGGCTCAACAAAAAC

CCCCCTGGTCCTAGCACATCA |

58°C | 575 bp |

Flow cytometry

Total splenocytes were collected by mechanical disruption of spleens. Bone marrow (BM) cells were harvested by flushing femur and tibia with PBS containing 3% FCS. Red blood cells in cell suspensions were lysed by incubation in hypotonic solution. Cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for mouse IgM, IgD, B220 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), CD2, CD43 (BD Pharmigen, Palo Alto, CA). Samples were run on a FACScalibur flow cytometer and analyzed using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lanes, NJ).

LPS cultures

For in vitro LPS cultures, spleen B cells from 6- to 12-weeks old mutant and control mice were first positively selected with anti-CD19 magnetic beads using LS columns (Miltenyi Biotec) and then cultured for 3 days in complete RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FCS and 20 μg/ml LPS. Dead cells were removed by centrifugation on Lympholyte M gradient before DNA extraction from cultured cells.

Long-term bone marrow cultures

Long-term bone marrow cultures were established from freshly harvested bone marrow cells using IL7-supplemented RPMI medium, 10% FBS, as described (27). Suspensions cells from parallel cultures were repeatedly harvested from weeks 4 to 8, and used directly for RNA or DNA extraction, or frozen at −80°C for long-term storage.

RT- and quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from splenocytes and BM using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), contaminating DNA was removed with the “DNA-free” kit (Ambion, Austin, TX), and reverse transcription was carried out with the Superscript first strand cDNA synthesis kit(Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Serial dilutions of cDNAs were amplified by PCR using the primer pairs listed in Table I. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) with SYBR Green I fluorescent dye (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and primers specific for μ0 and mb-1 transcripts (Table I) was carried out using a RotorGene real-time DNA amplification system (Corbett Research, Sydney, Australia) and the following amplification parameters: 95°C for 15 min, then 42 cycles of 94 °C for 30 sec, 61 °C for 30 sec and 72 °C for 30 sec. Melting curve and data analysis of PCR products was performed using RotorGene analysis software, and the comparative CT method was used for relative quantitation of the μ0 levels, normalized to Mb-1 expression (28).

Methylation analysis

Genomic DNA from long term-bone marrow culture cells or day 4 LPS-stimulated B lymphoblasts was extracted by SDS/proteinase K digestion and isopropanol precipitation. Purified DNA (30 μg) was first digested with Hind III endonuclease. After ethanol precipitation, one third of digested DNA was additionally treated with either MspI or with its methylation-sensitive isoschizomer Hpa II. Digested samples were resolved by gel electrophoresis using 0.8% agarose gel, then blotted to nylon membranes and analyzed sequentially by Southern hybridization using either a 2.2 kb HindIII fragment spanning the region from 5′ of DQ52 to the JH1 segment or a PCR-amplified 575bp fragment mapping between DQ52 and JH1 (see primers in Table I), followed by a 0.7 kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment probe spanning the Iμ region immediately 3′ of the Eμ enhancer site.

Results

Generation of ΔEμ and SV40eR mice

Targeting constructs were generated using 129-strain genomic DNA and carrying either a complete deletion of Eμ’s 272 bp SspI-PpuMI fragment (ΔEμ), or its replacement with a 275 bp SV40 enhancer core fragment from Clontech’s pEGFP-C2 vector (SV40eR) (Fig. 1A). The linerarized constructs were transfected into the (129SvXC57Bl/6J)F1 ES cell line F1.11 (a gift from Barry Sleckman, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO). After selection and screening (Fig. 1B), cells from 2 (ΔEμ) or 3 (SV40eR) targeted clones for each construct were injected into C57Bl/6 blastocysts and the chimeras obtained were bred first with C57Bl/6 mice to obtain germline transmission (Fig. 1C). Finally, germline mutant mice were bred with EIIA-Cre transgenic mice (25) to eliminate the G418-resistance gene, and the resulting progeny (Fig. 1D) selected and bred for analysis. The results presented hereafter are from one germline ΔEμ clone and 2 independent germline-transmitting, phenotypically indistinguishable SV40eR clones.

Figure 1. Targeting and screening strategy.

A. Maps of the IgH locus and targeting constructs. Relevant restriction enzyme sites (R, EcoRI; B, BamHI; S, SspI; P, PpuMI; H, HindIII) are indicated. 1. Structure of the endogenous IgH locus, with the position of DQ52 and JH segments, Eμ core (filled circle) and MARs (gray boxes), and Cμ exons 1 and 2. 2. Targeting construct for the ΔEμ mutation, with LoxP sites (striped boxes) flanking a G418-resistance marker (neo), and a thymidine kinase negative selection marker (tk) outside of the 3′ homology arm. The site of insertion of the SV40 enhancer (SV40e, open oval) is marked. 3. Structure of the ΔEμ targeted locus (site of insertion of the SV40e in the SV40eR mutants is indicated below). PCR primers used for screening for germline transmission (PGK-F and Smu-B, Table I) are indicated by arrows. 4. Structure of the ΔEμ targeted locus after Cre-mediated deletion of the neo gene (site of insertion of the SV40e in the SV40eR mutants is indicated below). PCR primers used for screening for deletion (UDEμ-F and UDEμ-B, Table I) are indicated by arrows. B. Southern blot analysis of targeted ΔEμ (left) and SV40eR (right) ES cell clones. Genomic DNAs were digested with BamHI and hybridized with the 5′Cμ probe (position shown in A.1. above). IgH a and b alleles in F1.11 cells generate fragments of about 8 and 9 kb, respectively, while successful integration of the targeting construct gene results in insertion of a new BamHI site and generates bands of 7.5 kb. C. PCR screening for germline transmission of the ΔEμ-neo and SV40eR-neo mutations. Wild-type alleles do not amplify with the PGK-F and Smu-B primer pair, since the former maps to the neo marker and the latter is outside the construct homology region. D. PCR screening for Cre-mediated neo deletion. Using the UDEμ-F and UDEμ-B primer pair, wild-type alleles give rise to a 393 bp band, ΔEμ alleles to a 283 bp band and SV40eR to a 503 bp band.

B cell characterization in ΔEμ and SV40eR mice

To initially characterize B cell development in the two strains, B cell populations from spleen and bone marrow of homozygous ΔEμ, SV40eR and control C57Bl/6 mice were stained with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies to various B cell markers and analyzed by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 2 and Table II, both ΔEμ and SV40eR mice displayed a significant decrease in absolute numbers and percentages of pre-B, immature B and recirculating mature B cells in the bone marrow, and of IgM+/B220+ B cells in the spleen, a deficiency that is slightly more severe in SV40eR than ΔEμ mice. This phenotype, consistent with previous observations in other Eμ-deficient mice (2, 3, 5, 7), points to a similar B cell developmental defect in ΔEμ and SV40eR mice, suggesting that the SV40 enhancer cannot fully complement Eμ activity in B cell development.

Figure 2. Flow cytometry of B cell populations in ΔEμ and SV40eR mice.

Bone marrow (BM, top panels) and spleen (bottom panels) cells from ΔEμ, SV40eR and control mice were analyzed by flow cytometry with the indicated antibodies. B220-low, CD2+ pre-B cells were significantly decreased in both mutants strains and were mature B220+, IgM+ cells in the spleen. Data are representative of 5–10 mice/strain.

Table II.

B cells in ΔEμ and SV40eR bone marrow and spleen

| Wild-type | SV40eR | ΔEμ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow | |||

| Pro-B (B220+, IgM−, CD2−, CD43+) | |||

| Abs. ×10−6 (st.dev) | 0.5 (±0.4) | 0.6 (±0.4) | 0.5 (±0.4) |

| % (st.dev) | 1.2 (±0.9) | 1.4 (±1.1) | 1.5 (±1.3) |

| Pre-B (B220+, IgM−, CD2+, CD43−) | |||

| Abs. ×10−6 (st.dev) | 2.3 (±1.5) | 0.7 (±0.6)* | 0.8 (±0.6)* |

| % (st.dev) | 0.9 (±0.5) | 0.3 (±0.3)* | 0.2 (±0.1)** |

| Immature B (B220low/int, IgMhigh) | |||

| Abs. ×10−6 (st.dev) | 4.6 (±0.3) | 0.3 (±0.2)*** | 0.6 (±0.3)*** |

| % (st.dev) | 2.7 (±1.1) | 0.9 (±0.7)** | 0.2 (±0.1)** |

| Recirculating B (B220high, IgMlow) | |||

| Abs. ×10−6 (st.dev) | 4.3 (±0.6) | 0.7 (±0.6)*** | 0.8 (±0.5)*** |

| % (st.dev) | 10.9 (±3.5) | 1.9 (±1.6)** | 3.6 (±1.8)** |

| Spleen | |||

| B cells (B220+, IgM+) | |||

| Abs. ×10−6 (st.dev) | 52.5 (±16.7) | 5.8 (±2.6)** | 10.8 (±4.1)** |

| % (st.dev) | 31.1 (±6.3) | 10.5 (±3.3)** | 20.4 (±3.3)* |

= p<0.05;

= p<0.01,

= p<0.001 (2-tailed Student’s t-test)

VDJ recombination analysis

The apparent block in B cell development in ΔEμ and SV40eR mice is consistent with diminished VDJ recombination activity, as previously reported for other Eμ-deficient animals (2, 3, 5, 7). To assess VDJ rearrangement status of ΔEμ and SV40eR mutated alleles we analyzed genomic DNA from magnetically sorted CD19-positive mature splenic B cells stimulated with LPS for 3 to 4 days. Although treatment with LPS may amplify various B cell subsets differentially, any such difference is unlikely to introduce bias with respect to the rearrangement status of the non-expressed allele, and serves to significantly increase the purity of the sample, and thus reduce the contamination from non-rearranged alleles from non-B cell DNA, which is critical when dealing with low rates of unrearranged alleles in wild-type controls.

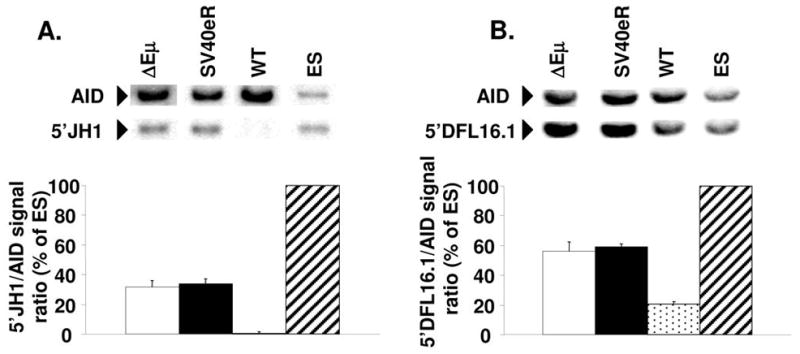

Southern blot and densitometrical analysis was used to assess the retention of sequences upstream of the JH1 segment (deleted upon D-J rearrangement) and of the most distal DH segment, DFL16.1 (deleted upon V-DJ rearrangement) on the non-functional alleles of ΔEμ, SV40eR and control mice. The productively rearranged alleles having of course lost both sequences, the hybridization signal reflects specifically the retention of the sequences in question on the non- functional alleles. Hybridization with a probe specific for a non-rearranging gene, AID, was used for normalization.

In normal mature B cells, only a small fraction of non-functional alleles (0–5%) are known to remain in germline configuration, while in various strains of Eμ-deficient mice this fraction is increased to 30–40% (2, 5, 7). Consistent with these previous observations, in our experiments 5′-JH1 sequences were essentially undetectable in normal B cells, while over 30% of the hybridization signal was retained in ΔEμ B cells (Fig. 3A). SV40eR B cells showed a similar picture to ΔEμ mutants, indicating that a significant portion of non-functional alleles remained in germline configuration.

Figure 3. Analysis of IgH rearrangement in ΔEμ and SV40eR mice.

Genomic DNA from day-4 LPS-stimulated B cell cultures from mutant and wild-type mice and from parental E2-1 ES cells were digested with Hind III, blotted and hybridized with probes for AID and a region upstream of JH1 (A), or digested with EcoRI, blotted and hybridized with probes for AID and a region upstream of DFL16.1 (B). Each experimental lane contained DNA from 2 pooled parallel cultures after magnetically sorting for CD19+ cells and Ficoll gradient purification of dead cells. The graphs show averages and standard deviations from 3 independent experiments (6 experimental mice). Hybridization signals from AID and IgH sequences were quantified using ImageQuant software after exposure to fluorescent screens, the signal ratios of IgH/AID in each lane was calculated and normalized to ES cell signal ratio (100% retention because of lack of rearrangement). Note the almost complete D-JH rearrangement of non-expressed alleles in wild-type cells (about 0% residual signal for 5′JH1) vs about 30% 5′JH1 retention in ΔEμ and SV40eR cells (A). Similarly, ΔEμ and SV40eR non-expressed alleles show almost complete lack of VH-DJ rearrangement (about 50% retention of 5′DFL16.1 signal) while wild-type alleles show substantial VH-DJ rearrangement (20% 5′DFL16.1 retention, 60% rearrangement).

With respect to V- to DJ rearrangement, in normal B cells we found that about 40% of nonfunctional alleles only display rearranged DJ segments, with no VH segment involvement, resulting in 5′-DFL16.1 hybridization signal retention of 20%. In ΔEμ and SV40eR B cell DNAs, on the contrary, about 50% of the 5′-DFL16.1 hybridization signal was retained, indicating that the non-functional alleles almost entirely lacked V-DJ rearrangements (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that SV40eR and ΔEμ alleles display a significant decrease in VDJ recombination activity at both the D-J and the V-DJ recombination step. However, leakiness of rearrangement on both backgrounds is sufficient to allow detectable, if diminished, B cell development.

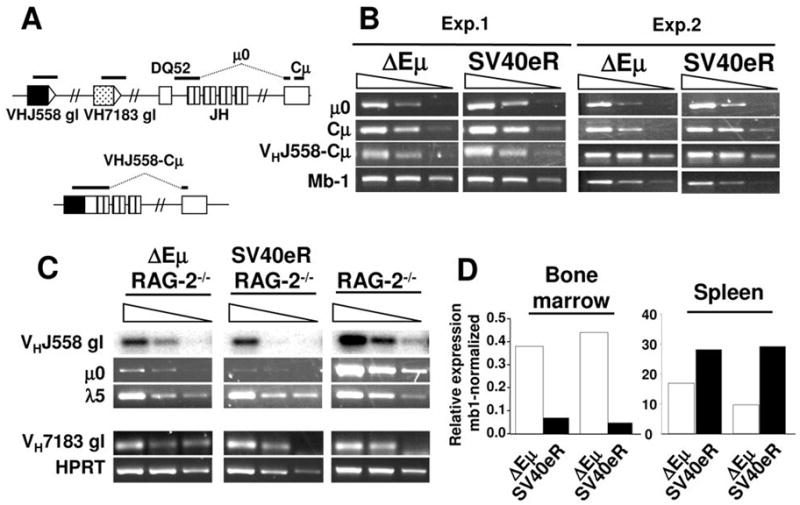

Transcriptional activity of ΔEμ and SV40eR alleles

Expression of surface Ig and differentiation of B lymphocytes in ΔEμ and SV40eR homozygotes clearly indicates that both types of mutations are compatible with gene transcription through the IgH locus. However, this may be the result of intrinsic selection for rare transcriptionally active alleles, since lack of Ig expression is known to cause apoptosis of mature B cells (29). To control for this possibility, we analyzed CD19+ sorted mature B cells from Δ ΔEμ and SV40eR mice for expression of the non-functional alleles, which are under no known selective constraint, using RT-PCR and qPCR with primers specific for μ0 germline transcripts. Significant levels of transcripts were observed in both mutant strains, with SV40eR mutants showing about 2- to 3-fold higher expression compared to ΔEμ, consistent with the possibility of transcriptional enhancement from the SV40e element (Fig. 4B, D). A similarly slightly higher mRNA level was observed for mature, rearranged transcripts of the VH J558 and 7183 families (Fig. 4B and not shown).

Figure 4. IgH germline transcript expression in ΔEμ and SV40eR mice.

A. Schematics of the location of transcripts analyzed by RT-PCR in these experiments (not in scale). Top, germline region, bottom, rearranged J558 region. Note that the μ0 and VHJ558-Cμ transcripts amplified regions span spliced exons. B. RT-PCR analysis of IgH transcripts in CD19-purified mature splenic B cells. Serial 10-fold dilutions of cDNA samples were analyzed with the following primer pairs, μ0: Mu0 and GLμR; Cμ: CμAH-F and CμAH-B; VHJ558-Cμ, VHJ558S and GLμR; Mb-1, Mb1-F and Mb1-B (see also Table I). Two of 3 independent experiments are shown. C. RT-PCR analysis of IgH transcripts in bone marrow pro-B cells of ΔEμ/RAG2−/−, SV40eR/RAG2−/− and RAG2−/− controls. Primer pairs were: μ0: Mu0 and GLμR; germline VHJ558: VHJ558 and J558Sp2; l5: λ5-F and λ5-B (Table I). VHJ558 germline transcripts RT-PCR products were blotted and hybridized with internal J558-specific oligonucleotide probe VHJ558Sc. D. qPCR analysis of μ0 expression in SV40eR and ΔEμ bone marrow (left) and spleen (right) samples, obtained as described in panels A and B. Note how SV40eR alleles express 7- to 10-fold lower μ0 transcripts compared to ΔEμ in the bone marrow, but 1.7–3 fold higher levels in mature B cells.

To better elucidate the role of IgH transcriptional activity in VDJ recombination of ΔEμ and SV40eR alleles, we bred both mutations into the RAG2-deficient background, in which B cell differentiation is arrested at the pro-B cell stage (26) and analyzed expression of μ0 transcripts at this critical stage. Strikingly, little or no IgH locus expression was detected in SV40eR mutants, while ΔEμ pro-B cells, as already reported for similar mutants, express reduced but clearly detectable transcripts (Fig. 4C, D). qPCR quantifies the reduction of μ0 transcripts in SV40eR bone marrow compared to ΔEμ as 7- to 10-fold (Fig. 4D). Expression of germline VH transcripts from 7183 VH family segments was comparable in controls and targeted B cells, while the large VH J558 gene family was expressed at partially lower levels in both mutant strains compared to controls (Fig. 4C).

DNA methylation changes associated with the ΔEμ and SV40eR mutations

To further investigate the functional status of the IgH locus in the ΔEμ and SV40eR mutants, we decided to analyze the levels of DNA methylation. To obtain sufficiently pure material from early B cell precursors, we established IL7-supplemented long-term bone marrow cultures (LTBMC) from RAG2−/−, ΔEμ and SV40eR mutants. After 4–8 weeks in culture, virtually all (>98%) suspension cells in these cultures consist of CD19+, CD43+ pro-B cells (not shown). Genomic DNA methylation status at specific IgH sites (Fig. 5A) was established using MspI/HpaII restriction analysis. Hybridization with probes specific for either the DQ52-JH1 region or the Iμ exon (immediately 3′ of Eμ or the introduced mutations) showed that both SV40eR and ΔEμ loci were almost completely methylated at both JH and Iμ-proximal sites (Fig. 5B). When DNA methylation at the same sites was assayed in mature B cell cultures, however, SV40eR mutants showed complete demethylation of both JH and Iμ-proximal sites, contrary to ΔEμ mutants, in which ~10% of sites in both regions remain methylated (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. IgH locus DNA methylation in ΔEμ and SV40eR B cells.

IgH locus DNA methylation was analyzed by digestion of genomic DNAs from the indicated sources with Hind III alone, or HindIII and either MspI or its methylation-sensitive isoschizomere HpaII. Resistance to digestion with HpaII compared to MspI indicates methylation of the site. A. Map of the relevant sites in the wild-type and mutant IgH loci (H, HindIII; M/H, MspI/HpaII, not in scale) and probes position. B. Southern blot analysis of DNA from cells harvested from IL7-supplemented LTBMCs of the indicated mice (>95% B220+, CD43+ pro-B cells). Blots were sequentially hybridized with probes spanning either the entire DQ52-JH1 region (top) or the Iμ exon (bottom). Unlike IgH-wild-type B cells, both SV40eR and ΔEμ alleles show only limited demethylation at the JH locus. C. Southern blot analysis of DNA from magnetically sorted CD19+ LPS-stimulated splenic B cells from the indicated mice (>95% B220+ B cells). Digestion patterns are as indicated in panel C. Blots were sequentially hybridized with a probe spanning either the DQ52-JH1 interval (to avoid hybridization with DQ52-JH rearranged alleles) (top panel) or the Iμ exon (bottom panel). Both SV40eR and wild-type alleles are completely demethylated and both JH and Iμ-proximal sites, while ΔEμ alleles show incomplete, although significant, demethylation. Note that the wild-type sample shows little DQ52-JH signal because of almost complete deletion of this region by VDJ rearrangement. 1 of 2 independent experiments shown.

Thus, the observed decrease in VDJ recombination in SV40eR mutants is associated with active inhibition of transcription and deficient de-methylation of IgH loci in pro-B cells caused by the SV40e. However, as development progresses, the suppression mechanism is released, SV40e becomes active as an enhancer, generating μ0 transcripts and driving proximal DNA demethylation to a larger extent than ΔEμ mutants.

Discussion

A large body of evidence supports the critical role of enhancer elements of Ig and T cell receptor (TCR) loci in mediating not only transcriptional regulation, but also stage- and lineage-specificity of VDJ recombination, as well as additional mechanisms such as somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination (reviewed in 10, 12–14). Despite this extensive literature, however, the precise mechanisms by which these elements exert their varied functions are still only partially understood. In particular, enhancer-dependence and -specificity as assayed in recombination substrates and transgenic systems have often proven more stringent than the corresponding activities of endogenous sequences. As a consequence, a general picture has emerged which suggests that regulation of endogenous Ig and TCR loci is the result of complex interactions between multiple elements and signals rather than of individual regulatory sequences.

In this manuscript, we set out to address the critical issue of whether generalized transcriptional enhancer activity is sufficient to mediate at least some of the activities carried out by the intronic Eμ enhancer, or whether a specificity requirement exists for this element. The evidence provided clearly points to the second conclusion, albeit in an unexpected fashion.

Although SV40e is known to provide a strong, general enhancer activity in almost every cell type tested, including lymphoid cells (30, 31; reviewed in 32), our observations indicate that it is not capable of complementing a deletion of the Eμ enhancer with respect to IgH locus function. Contrary to what would have been our prediction, however, this is not associated simply with SV40e’s lack of activity, or its inability to mediate some of the more specialized functions of Eμ, such as recruitment of the VDJ-rearrangement machinery, but to suppression of IgH germline transcription early during B cell development. In fact, the data presented here show that SV40e replacement of Eμ exerts an active inhibitory effect on germline transcription that goes beyond the simple lack of Eμ sequences. This situation is reminiscent of the negative effect of insertion of phosphoglycerate kinase (pgk) promoter-driven selection cassettes in various positions within the IgH locus, including upstream of Eμ (2, 3, 33–36). However, while those findings were attributed to promoter competition effects, this is unlikely the case for SV40e, which is not known to harbor any intrinsic promoter activity. Thus, the most likely explanation is that not promoter competition alone, but the disruption of a higher-order IgH control system, possibly mediated by the interplay of multiple regulatory elements, is responsible for pro-B cell-specific IgH transcriptional suppression by the inserted SV40e.

There are two components to the SV40e-mediated negative effects. First, SV40e appears unable to mediate the extensive Eμ-dependent DNA demethylation required for full activation of IgH. This finding mirrors data by Forrester and colleagues showing that SV40e can replace Eμ as a transcriptional enhancer on demethylated artificial constructs in vitro, but unlike Eμ it cannot cooperate with MAR sequences to drive long-range demethylation of artificially methylated sequences (37). Indeed, methylation of IgH was essentially unchanged in SV40eR vs ΔEμ LTBMC pro-B cells, as opposed to the largely demethylated normal loci.

The observation of low but detectable VDJ rearrangement in the absence of substantial μ0 transcription in endogenous pro-B cells is surprising, although not completely unprecedented. Untranscribed gene segments undergo active V-DJ rearrangement in both artificial substrates and endogenous loci, and insertion of a neor gene upstream of Eμ suppresses IgH transcription, but allows detectable locus rearrangement (36, 38, 39). Furthermore, Eμ has been shown to be able to mediate locus accessibility in the absence of active transcription (40). Thus, the cis-acting structural and topological modifications which determine VDJ recombination accessibility can be uncoupled from the process of transcription. A second, not mutually exclusive possibility is that IgH expression in the SV40eR and neor-insertion mutants is variegated, as recently demonstrated for IgH transgenes bearing weakened enhancer elements (41). A very small fraction of SV40eR cells transcribing IgH at normal levels would still be able to progress to the pre-B cell stage and undergo expansion, while the majority would be transcriptionally silent and recombinationally inactive. The fact that B cell development is somewhat more severely inhibited in SV40eR than in ΔEμ mice, although recombination rates on the non-functional alleles are similar between the two mutants, would seem to support the latter scenario, with the difference between the mutants residing in the fraction of recombinationally active cells, rather than in a stochastic reduction of recombination efficiency across all cells.

Regardless of the mechanism allowing IgH VDJ recombination in SV40eR pro-B cells, the inhibitory effect exerted by SV40e is specific to early B cell progenitors, as mature SV40eR B cells not only express high levels of functional Ig transcripts, but also of μ0 transcripts emanating from non-rearranged alleles, which are under no known selective constraint. Indeed, μ0 levels in SV40eR mature B cells are higher than those in ΔEμ mature B cells, suggesting not only that the transcriptional suppression observed at the pro-B cell stage is relieved at this stage, but that SV40e has assumed an active enhancer role of in these cells. Consistent with this possibility, SV40eR mutant mature B cells show complete demethylation of IgH loci, unlike ΔE μ mutants.

DNA methylation has been shown to play an important role in VDJ rearrangement, regulating allelic exclusion of the IgH locus as well as accessibility to recombination of transgenic substrates (42–44). Although direct evidence for any role of DNA methylation at the IgH locus is missing, Abelson virus-transformed precursor B cell lines from mice bearing a replacement of Eμ with a neor gene showed that lack of demethylation on the targeted alleles is associated with the block in VDJ recombination (3). We show here that although IgH is almost completely methylated in pro-B cells lacking Eμ, de-methylation accrues as B cell development progresses even in the absence of the enhancer, and is significant, although still incomplete, in mature ΔEμ B cells. Also importantly, residual methylation is found equally on rearranged and non-rearranged ΔEμ alleles, because the fraction of methylated, unrearranged alleles (that is, about 15% methylated loci of the 15–20% left in germline configuration, i.e. up to 3% of total) cannot account for the total fraction of loci methylated at Iμ-proximal sites (>10%). This suggests that demethylation is not an absolute prerequisite for either VDJ recombination or IgH expression. Unlike ΔEμ loci, demethylation is complete on SV40eR alleles mature B cells, indicating a direct role of SV40e in this process, albeit at a later differentiation stage than pro-B cells.

Although persistent IgH DNA methylation can be at least partly responsible for the inhibition in VDJ recombination observed in ΔEμ and SV40eR mutants, it does not explain the additional inhibition of transcription caused in pro-B cells by SV40e. The evidence for differential and stage-dependent (early inhibitory vs late activating) SV40e activity strongly argues for a modelof IgH regulation involving compatibility of multiple control elements in coordinated locus expression. For instance, IgH locus expression has been correlated with the temporal localization of the expressed alleles in specific nuclear compartments (45). In addition, specific holo-complex formation between distant regulatory elements has been implicated in regulating the function of the TCRβ locus (46). Differential effects of transcription factor binding on locus accessibility in different contexts and at different developmental stages have been shown for PU. 1 activity at the Eμ and 3′Eκ enhancers (47, 48). Any perturbation of these or analogous higher-order processes by inappropriate transcription factor recruitment and/or local chromatin modifiers may result in further inhibition beyond that caused by the simple lack of the Eμ element. The SV40eR mutants offer therefore a unique opportunity to probe these elusive mechanisms by establishing the basis for their inhibition.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Barry Sleckman for kindly providing ES cells, Jianzhu Chen for IgH genomic DNA clones, Craig Jordan and John Manis for critically reviewing the manuscript. We also thank David Heinrich for technical support. This work was supported by NIH grant RO1 AI45012 to AB.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grant RO1 AI45012 to A.B.

Abbreviations: CSR, class switch recombination; LTBMC, long-term bone marrow culture; MAR, matrix attachment region; MZ, marginal zone; SHM, somatic hypermutation.

References

- 1.Ernst P, Smale ST. Combinatorial regulation of transcription II: The immunoglobulin mu heavy chain gene. Immunity. 1995;2:427–438. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serwe M, Sablitzky F. V(D)J recombination in B cells is impaired but not blocked by targeted deletion of the immunoglobulin heavy chain intron enhancer. Embo J. 1993;12:2321–2327. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Young F, Bottaro A, Stewart V, Smith RK, Alt FW. Mutations of the intronic IgH enhancer and its flanking sequences differentially affect accessibility of the JH locus. Embo J. 1993;12:4635–4645. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bottaro A, Young F, Chen J, Serwe M, Sablitzky F, Alt FW. Deletion of the IgH intronic enhancer and associated matrix-attachment regions decreases, but does not abolish, class switching at the mu locus. Int Immunol. 1998;10:799–806. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.6.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakai E, Bottaro A, Davidson L, Sleckman BP, Alt FW. Recombination and transcription of the endogenous Ig heavy chain locus is effected by the Ig heavy chain intronic enhancer core region in the absence of the matrix attachment regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1526–1531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakai E, Bottaro A, Alt FW. The Ig heavy chain intronic enhancer core region is necessary and sufficient to promote efficient class switch recombination. Int Immunol. 1999;11:1709–1713. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.10.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perlot T, Alt FW, Bassing CH, Suh H, Pinaud E. Elucidation of IgH intronic enhancer functions via germ-line deletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14362–14367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507090102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ronai D, Iglesias-Ussel MD, Fan M, Shulman MJ, Scharff MD. Complex regulation of somatic hypermutation by cis-acting sequences in the endogenous IgH gene in hybridoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11829–11834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505449102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cobb RM, Oestreich KJ, Osipovich OA, Oltz EM. Accessibility control of V(D)J recombination. Adv Immunol. 2006;91:45–109. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)91002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung D, Giallourakis C, Mostoslavsky R, Alt FW. Mechanism and control of V(D)J recombination at the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:541–570. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sen R, Oltz E. Genetic and epigenetic regulation of IgH gene assembly. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sleckman BP. Lymphocyte antigen receptor gene assembly: multiple layers of regulation. Immunol Res. 2005;32:253–258. doi: 10.1385/IR:32:1-3:253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krangel MS, Carabana J, Abbarategui I, Schlimgen R, Hawwari A. Enforcing order within a complex locus: current perspectives on the control of V(D)J recombination at the murine T-cell receptor alpha/delta locus. Immunol Rev. 2004;200:224–232. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlissel MS. Regulation of activation and recombination of the murine Igkappa locus. Immunol Rev. 2004;200:215–223. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Afshar R, Pierce S, Bolland DJ, Corcoran A, Oltz EM. Regulation of IgH gene assembly: role of the intronic enhancer and 5′DQ52 region in targeting DHJH recombination. J Immunol. 2006;176:2439–2447. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bachl J, Olsson C, Chitkara N, Wabl M. The Ig mutator is dependent on the presence, position, and orientation of the large intron enhancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2396–2399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin MM, Green NS, Zhang W, Scharff MD. The effects of E mu, 3′alpha (hs 1,2) and 3′kappa enhancers on mutation of an Ig-VDJ-Cgamma2a Ig heavy gene in cultured B cells. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1121–1129. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.8.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinoshita K, Tashiro J, Tomita S, Lee CG, Honjo T. Target specificity of immunoglobulin class switch recombination is not determined by nucleotide sequences of S regions. Immunity. 1998;9:849–858. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80650-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee CG, Kinoshita K, Arudchandran A, Cerritelli SM, Crouch RJ, Honjo T. Quantitative regulation of class switch recombination by switch region transcription. J Exp Med. 2001;194:365–374. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oltz EM, Alt FW, Lin WC, Chen J, Taccioli G, Desiderio S, Rathbun G. A V(D)J recombinase-inducible B-cell line: role of transcriptional enhancer elements in directing V(D)J recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6223–6230. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blackwell TK, Moore MW, Yancopoulos GD, Suh H, Lutzker S, Selsing E, Alt FW. Recombination between immunoglobulin variable region gene segments is enhanced by transcription. Nature. 1986;324:585–589. doi: 10.1038/324585a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrier P, Krippl B, Blackwell TK, Furley AJ, Suh H, Winoto A, Cook WD, Hood L, Costantini F, Alt FW. Separate elements control DJ and VDJ rearrangement in a transgenic recombination substrate. Embo J. 1990;9:117–125. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bories JC, Demengeot J, Davidson L, Alt FW. Gene-targeted deletion and replacement mutations of the T-cell receptor beta-chain enhancer: the role of enhancer elements in controlling V(D)J recombination accessibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7871–7876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inlay MA, Lin T, Gao HH, Xu Y. Critical roles of the immunoglobulin intronic enhancers in maintaining the sequential rearrangement of IgH and Igk loci. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1721–1732. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lakso M, Pichel JG, Gorman JR, Sauer B, Okamoto Y, Lee E, Alt FW, Westphal H. Efficient in vivo manipulation of mouse genomic sequences at the zygote stage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5860–5865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shinkai Y, Rathbun G, Lam KP, Oltz EM, Stewart V, Mendelsohn M, Charron J, Datta M, Young F, Stall AM, et al. RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell. 1992;68:855–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young F, Ardman B, Shinkai Y, Lansford R, Blackwell TK, Mendelsohn M, Rolink A, Melchers F, Alt FW. Influence of immunoglobulin heavy- and light-chain expression on B-cell differentiation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1043–1057. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam KP, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K. In vivo ablation of surface immunoglobulin on mature B cells by inducible gene targeting results in rapid cell death. Cell. 1997;90:1073–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mercola M, Goverman J, Mirell C, Calame K. Immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer requires one or more tissue-specific factors. Science. 1985;227:266–270. doi: 10.1126/science.3917575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davidson I, Fromental C, Augereau P, Wildeman A, Zenke M, Chambon P. Cell-type specific protein binding to the enhancer of simian virus 40 in nuclear extracts. Nature. 1986;323:544–548. doi: 10.1038/323544a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atchison ML. Enhancers: mechanisms of action and cell specificity. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1988;4:127–153. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cogne M, Lansford R, Bottaro A, Zhang J, Gorman J, Young F, Cheng HL, Alt FW. A class switch control region at the 3′ end of the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus. Cell. 1994;77:737–747. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manis JP, van der Stoep N, Tian M, Ferrini R, Davidson L, Bottaro A, Alt FW. Class switching in B cells lacking 3′ immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancers. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1421–1431. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seidl KJ, Manis JP, Bottaro A, Zhang J, Davidson L, Kisselgof A, Oettgen H, Alt FW. Position-dependent inhibition of class-switch recombination by PGK-neor cassettes inserted into the immunoglobulin heavy chain constant region locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3000–3005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delpy L, Decourt C, Le Bert M, Cogne M. B cell development arrest upon insertion of a neo gene between JH and Emu: promoter competition results in transcriptional silencing of germline JH and complete VDJ rearrangements. J Immunol. 2002;169:6875–6882. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forrester WC, Fernandez LA, Grosschedl R. Nuclear matrix attachment regions antagonize methylation-dependent repression of long-range enhancer-promoter interactions. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3003–3014. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsieh CL, McCloskey RP, Lieber MR. V(D)J recombination on minichromosomes is not affected by transcription. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15613–15619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angelin-Duclos C, Calame K. Evidence that immunoglobulin VH-DJ recombination does not require germ line transcription of the recombining variable gene segment. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6253–6264. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jenuwein T, Forrester WC, Qiu RG, Grosschedl R. The immunoglobulin mu enhancer core establishes local factor access in nuclear chromatin independent of transcriptional stimulation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2016–2032. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins C, Azmi P, Berru M, Zhu X, Shulman MJ. A weakened transcriptional enhancer yields variegated gene expression. PLoS ONE. 2006;1:e33. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Engler P, Haasch D, Pinkert CA, Doglio L, Glymour M, Brinster R, Storb U. A strain-specific modifier on mouse chromosome 4 controls the methylation of independent transgene loci. Cell. 1991;65:939–947. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90546-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsieh CL, Lieber MR. CpG methylated minichromosomes become inaccessible for V(D)J recombination after undergoing replication. Embo J. 1992;11:315–325. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mostoslavsky R, Singh N, Kirillov A, Pelanda R, Cedar H, Chess A, Bergman Y. Kappa chain monoallelic demethylation and the establishment of allelic exclusion. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1801–1811. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skok JA, Brown KE, Azuara V, Caparros ML, Baxter J, Takacs K, Dillon N, Gray D, Perry RP, Merkenschlager M, Fisher AG. Nonequivalent nuclear location of immunoglobulin alleles in B lymphocytes. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:848–854. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oestreich KJ, Cobb RM, Pierce S, Chen J, Ferrier P, Oltz EM. Regulation of TCRbeta gene assembly by a promoter/enhancer holocomplex. Immunity. 2006;24:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nikolajczyk BS, Sanchez JA, Sen R. ETS protein-dependent accessibility changes at the immunoglobulin mu heavy chain enhancer. Immunity. 1999;11:11–20. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marecki S, McCarthy KM, Nikolajczyk BS. PU.1 as a chromatin accessibility factor for immunoglobulin genes. Mol Immunol. 2004;40:723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]