Abstract

Protoporphyrin IX is the last common intermediate between the haem and chlorophyll biosynthesis pathways. The addition of Mg directs this molecule toward chlorophyll biosynthesis. The first step downstream from the branchpoint is catalyzed by the Mg chelatase and is a highly regulated process. The corresponding product, Mg protoporphyrin IX, has been proposed to play an important role as a signaling molecule implicated in plastid-to-nucleus communication. In order to get more information on the chlorophyll biosynthesis pathway and on Mg protoporphyrin IX derivative functions, we have identified an Mg protoporphyrin IX methyltransferase (CHLM) knock-out mutant in Arabidopsis in which the mutation induces a blockage downstream from Mg protoporphyrin IX and an accumulation of this chlorophyll biosynthesis intermediate. Our results demonstrate that the CHLM gene is essential for the formation of chlorophyll and subsequently for the formation of photosystems I and II and cyt b6f complexes. Analysis of gene expression in the chlm mutant provides an independent indication that Mg protoporphyrin IX is a negative effector of nuclear photosynthetic gene expression, as previously reported. Moreover, it suggests the possible implication of Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester, the product of CHLM, in chloroplast-to-nucleus signaling. Finally, post-transcriptional up-regulation of the level of the CHLH subunit of the Mg chelatase has been detected in the chlm mutant and most likely corresponds to specific accumulation of this protein inside plastids. This result suggests that the CHLH subunit might play an important regulatory role when the chlorophyll biosynthetic pathway is disrupted at this particular step.

Keywords: Arabidopsis; genetics; metabolism; Cell Nucleus; metabolism; Chlorophyll; biosynthesis; Chloroplasts; genetics; metabolism; Cytochrome b6f Complex; metabolism; Gene Deletion; Gene Expression Regulation, Enzymologic; Gene Expression Regulation; Plant; Methyltransferases; antagonists & inhibitors; genetics; Photosystem I Protein Complex; metabolism; Photosystem II Protein Complex; metabolism; Protoporphyrins; metabolism; Signal Transduction; genetics

Keywords: plant, Arabidopsis thaliana, chloroplast development, chlorophyll biosynthesis, enzyme, Mg chelatase, Mg protoporphyrin IX methyltransferase, gene, knock-out mutant, post-transcriptional regulation, plastid to nucleus signaling, nuclear gene repression

Chloroplast development depends on the coordinated synthesis of chlorophylls and cognate proteins and on their specific integration into photosynthetic complexes (for a review see 1). Chlorophylls are Mg tetrapyrrole molecules resulting from condensation of δ-ALA. Insertion of Mg into protoporphyrin IX, the last common intermediate of haems and chlorophylls, is catalyzed by Mg chelatase, a membrane-interacting multisubunit enzyme containing 3 different soluble proteins: CHLH, CHLI, and CHLD (2–5). In the next step, Mg protoporphyrin IX is methylated by a membrane Ado-Met dependent methyltransferase. In Arabidopsis the gene At4g25080 or CHLM has been identified as encoding the methyltransferase enzyme and the product of this single gene has been reported to be present in the two chloroplast membrane systems: the envelope and the thylakoids (6). Whereas a sequence homologous to CHLM has been identified in tobacco (7), the existence in plants of an additional and quite dissimilar gene for Mg protoporphyrin IX methylation has not been totally excluded. Expression analysis of tobacco CHLM revealed posttranslational activation of methyltransferase activity during greening and direct interaction of CHLM with the CHLH subunit of Mg chelatase (7). Furthermore, analysis of tobacco plants expressing CHLM antisense or sense RNA led to the conclusion that methyltransferase activity is involved in the direct regulation of expression of some genes such as CHLH and LHCB (8).

The meaning of the dual localization of the methyltransferase in the chloroplast envelope and the thylakoids is puzzling for different reasons. On one hand, chlorophylls are expected to be synthesized in the thylakoids where chlorophyll binding proteins are inserted into photosystems. On the other hand, the envelope is devoid of chlorophyll but contains several chlorophyll precursors from protoporphyrin IX to protochlorophyllide (9). In addition most of the enzymes of this part of the chlorophyll synthesis pathway i.e. protoporphyrinogen oxidoreductase, Mg chelatase, Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester cyclase and protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase are present in or interact with the envelope (10–13).

One reason for the occurrence of the chlorophyll intermediates in the envelope could be that some chlorophyll-binding proteins that are synthesized in the cytosol need to associate with chlorophyll or chlorophyll precursors during import through the envelope. Supporting this hypothesis, manipulation of Chlamydomonas in vivo systems and mutagenesis of specific residues in the LHCB protein have shown that accumulation of physiological amounts of LHCB by plastids requires interaction of the protein with chlorophyll within the inner membrane of the envelope (14, 15). More recently, it was demonstrated that chlorophyllide a oxygenase (CAO) is involved in the regulated import and stabilization of the chlorophyllide b- binding light-harvesting proteins LHCB1 (LHCII) and LHCB4 (CP29) in chloroplasts (16).

Beside their direct role in pigment synthesis, some chlorophyll intermediates have been proposed to play an additional role in intracellular signaling. In Chlamydomonas, Mg protoporphyrin IX and Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester were shown to substitute for light in the induction of the nuclear gene HSP70 (17). In Arabidopsis, an increased accumulation of Mg protoporphyrin IX has been reported in Norfluorazon-treated plants in which photooxidation of the plastid compartment leads to the repression of nuclear photosynthesis-related genes (18, 19). Furthermore, a genetic screen based on the use of Norfluorazon has allowed the identification of a series of Arabidopsis gun (for genome-uncoupled) mutants that are deficient in chloroplast-to-nucleus signaling. Several of the corresponding mutations have been shown to affect genes coding for the protoporphyrin IX manipulating proteins CHLH, CHLD and GUN4 (19–21). In these mutants, Norfluorazon treatment induced only a moderate increase in Mg protoporphyrin IX level, correlated with partial derepression of transcription of the nuclear photosynthesis-related genes. This indicates a role of Mg protoporphyrin IX accumulation in the repression of these genes (19, 22).

However, this demonstration was based on manipulation of plants with Norflurazon that has obvious pleiotropic effects. Moreover, due to the possibility of substrate channeling occurring between Mg chelatase and Mg protoporphyrin IX methyltransferase, it was not possible to clearly distinguish the specific contributions of Mg Protoporphyrin IX and its methylester. Supporting the intricacy of the regulation, it has recently been shown that the barley xantha-l mutant, defective in the Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester cyclization step, has a non-gun phenotype in the presence of Norflurazon (23, 24). In the absence of Norflurazon, the mutant has a high level of LHCB gene expression despite the accumulation of Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester.

In the present work, we identify a chlm null mutant and analyze the role of the methyltransferase enzyme in chlorophyll synthesis and chloroplast development. We also assess the ability of the mutant to carry out plastid-to-nucleus signaling. The results reveal a high level of repression of nuclear photosynthesis-related genes and a specific accumulation of the CHLH subunit of the Mg chelatase. Functional implications of these results are discussed.

Experimental procedures

Plant material and growth conditions

The A. thaliana chlm mutant (ABN42 line) of the ecotype Wassilewskija (WS) was obtained from the INRA, Versailles, France. Plants were grown on Murashige and Skoog (MS, Duchefa) agar containing 0.5 % sucrose for 5 days under medium light (70 μmol photons m−2 s−1) before transfer to dim light (5 μmol photons m−2 s−1). Kanamycin selection of T-DNA containing seedlings was performed on medium supplemented with kanamycin (Sigma) at 50 mg L−1. For Norflurazon treatment, seeds from CHLM/chlm heterozygous plants were germinated on standard MS-agar and after 5 days of culture, seedlings were transferred onto new plates including 5 μM Norflurazon and cultivated for 6 more days under strong light (100 μmol photons m−2 s−1).

For complementation experiments, a pCambia derivative was obtained by cloning a EcoRI-HindIII fragment harboring the CaMV 35S promoter-GUS-NOST fusion from pBI221 (Clontech) in an EcoRI-HindIII digested pCambia 1200 vector. The XbaI-EcoRI CHLM cDNA from the SK+ derivative obtained by Block et al. (2002) was then inserted into an SstI-XbaI digested pCambia derivative using an EcoRI-SstI adaptor (5′-AATTAGCT-3′). The obtained binary vector was introduced into the GV3121 strain of Agrobacterium tumefaciens in order to transform CHLM/chlm heterozygous plants. The transformed plants were PCR-screened to identify CHLM/chlm heterozygous plants and self-pollinated.

The LHCII-LUC construct was introduced into the chlm mutant background by crossing a heterozygous CHLM/chlm plant with a homozygous CAB-LUC transgenic plant (25). The progeny was PCR-screened for the presence of chlm T-DNA and seeds were collected from positive plants. The next generation segregates for both chlm T-DNA and the CAB-LUC transgene and was used for the experiment.

The sequence encoding the putative CHLH transit peptide was amplified using TL350 (5′-GGATCCATGGCTTCGCTTGTGTATTCTCCATTC-3′) and TL352 (TCTAGAGACGATTTTCACCGTTCGGAAC-3′). The corresponding PCR fragment was subcloned into pGEM-T easy vector (Promega) and sequenced. The BamHI-XbaI fragment was then ligated in frame with the XbaI-SacI EYFP gene (Clontech) into the BamHI-SacI sites of a binary vector derived from pCambia 1300 by introduction of a HindIII-EcoRI CaMV 35S promoter and Nos-T terminator cassette from EL103 (26). The obtained binary vector was introduced into the GV3121 strain of Agrobacterium tumefaciens in order to transform CHLM/chlm heterozygous plants. The transformed plants were PCR-screened to identify CHLM/chlm heterozygous plants and self-pollinated.

PCR analyses

Genomic DNA was amplified using the Tag6 primer (5′-CACTCAGTCTTTCATCTACGGCA-3′) and a specific primer (TL251 5′-GGAACAGCTTCGATGAGCCTAGAG-3′) to screen for the presence of chlm T-DNA insertion. The endogenous copy of the gene as well as the cDNA used for complementation were followed by PCR reactions using TL251 and TL252 (5′-GTGAGACTGATGAAGTGAATCG-3′). Standard PCR conditions were used.

Pigment analysis

Extraction was done according to (27). 3 mg of cotyledons of 8 day plants were ground in 200μL dimethylformamide and incubated for 16 h in the dark and on ice. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation for 15 min at 13 000×g and its absorbance in visible light recorded.

Tetrapyrole intermediate analysis

Approximately 20 mg of frozen leaf material was homogenised in 500 μL acetone: 0.125M NH4OH (9:1, v/v) in the dark and centrifuged at 4°C. The supernatant was diluted with 1 mL grinding medium and extracted 3 times with 1 mL hexane. After the complete elimination of the hexane phase, the acetone phase was either directly used for fluorescence measurement or dried under argon before solubilization in methanol: 5 mM tetrabutylammonium phosphate (70:30 v/v) for HPLC analysis. Florescence emission spectra were recorded with a spectrofluorometer MOS-450 from Biologic at room temperature from 570 to 690 nm upon excitation at either 402 nm for detection of protoporphyrin IX, or 416 nm for detection of Mg protoporphyrin IX and Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester or 440 nm for detection of chlorophyllide. HPLC analysis was as described in (6) except that elution was monitored by absorbance detection at 420 nm and by fluorescence detection (λexcitation 420 nm/λemission 595 nm or λexcitation 420 nm/λemission 625 nm). Standards of protorporphyrin IX (Sigma), of Mg protoporphyrin IX (Porphyrin Product Inc.), of Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester prepared and identified as described in (6) were used. When required, plants were incubated overnight with 10 mM ALA and 5 mM MgCl2 in 10 mM Hepes pH 7.0 before extraction.

Protein extraction and immunoblot

Proteins were extracted from leaf material according to the method described by (28). Protein analysis and immunoblotting were performed as described previously (6). Primary antibodies were used at the following dilution: anti CHLM 1/1000, anti KARI 1/1000, anti HSP70b 1/1000, anti CF1 1/10000, anti CRD1 1/1000, anti IE37 1/3000, anti OEP21 1/500, anti PORA-PORB 1/1000, anti PORC 1/1000, anti LHCB2 (Agrisera) 1/5000, anti LHCA2 (Agrisera) 1/2000, anti Cytf 1/5000, anti CP43 1/500, anti D1 (Agrisera) 1/1000, anti CHLH 1/200, anti CHLD 1/500, anti CHLI 1/200, anti-GFP (Euromedex) 1/3000. Primary antibodies were detected using peroxidase-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG (Jackson Immuno Research) or goat antimouse IgG (BioRad) and the chemiluminescent detection system (ECL, Amersham).

RT-PCR and Northern blot analysis

For RT-PCR analysis, total RNA was isolated using the Invisorb Spin Plant RNA Mini Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitek) followed by a DNase treatment using the RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega). A PCR reaction was performed on RNA with primers for the RPL21 gene (5′-TCCACTGCGTCGACGTCTCG-3′ and 5′-CTCCAACTGCAACATTGGGCG-3′) to check for the absence of genomic DNA. Reverse transcription was performed on 500 ng total RNA using the ProSTAR First-Strand RT-PCR kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Stratagene). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was calibrated by non-saturating PCR reaction (22 cycles) using primers designed to amplify the EF1-4α cDNAs (5′-CTGCTAACTTCACCTCCCAG-3′ and 5′-TGGTGGGTACTCAGAGAAGG-3′). A parallel set of reactions without addition of reverse transcriptase was run as a quality control. To analyze CHLM expression, semi-quantitative RT-PCR was performed with TL251 and TL252 primers (see above). The luciferase reporter gene expression was analyzed using two specific primers (5′-CCCGGCGCCATTCTATCC-3′ and 5′-TGAAATCCCTGGTAATCCG-3′). For Northern blot analysis, total RNA was extracted as described by (29). 20μg total RNA were separated on agarose gel. RNA blot hybridization and membrane washing were performed on Hybond-N membrane (Amersham).

The IE37 probe was obtained by PCR amplification on RT reaction by using specific primers (5′-CACCTAGACTCTCGGTGGC-3′ and 5′-TTTGGGAACGATCTGATCC-3′). The 25S probe was used as a loading control (30).

Microscopy

Leaves were observed with an immersion 40x objective at room temperature by confocal laser scanning microscopy using a Leica TCS-SP2 operating system. EYFP and chlorophyll fluorescence were excited respectively at 488 nm and 633 nm. Fluorescence emission was collected from 500 to 535 nm for EYFP and from 643 to 720 nm for chlorophyll.

RESULTS

Characterization of an Mg protoporphyrin IX methyltransferase null mutant

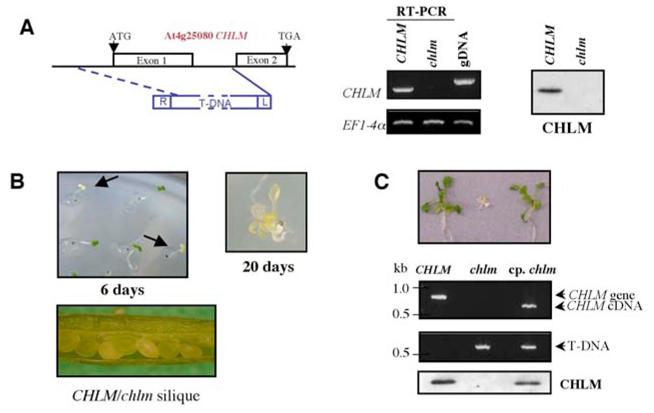

An Arabidopsis chlm mutant line was identified by screening the Flanking Sequence Tag database derived from the T-DNA insertion lines of the Versailles collection (31, 32) using the CHLM cDNA as query sequence (6) (Fig. 1A). PCR-genotyping and kanamycin selection resulted in the selection of plants that were heterozygous for insertion of a T-DNA in the CHLM gene. Sequencing of the PCR-genotyping product and further PCR analysis showed that the insertion of the T-DNA in the single intron present in the coding sequence resulted in the deletion of the 5′ part of the gene including the entire first exon (Fig. 1A). A mutant line with 3:1 kanamycin segregation as expected for a single genomic insertion was chosen for further analyses. Its progeny shows 1/3 of the kanamycin resistant plants being non green (Fig. 1B) and the yellow/white plants always exhibited a homozygous mutant genotype (Fig. 1C). Thus, the mutation in the CHLM gene is recessive and linked to the albino phenotype. In the homozygous mutant plants, RT-PCR indicated an absence of full-length CHLM transcript (Fig. 1A, middle) and immunoblotting confirmed the absence of CHLM protein (Fig. 1A, right and 1C).

Figure 1. Identification of a chlm mutant.

A- Left : Structure of the CHLM gene showing the position of the T-DNA insertion in the mutant. Boxes along the gene represent exons. The deletion created by the T-DNA insertion is shown by the dotted line. Middle: CHLM gene expression in wild-type plants and homozygous mutants shown by RT-PCR on seedlings. gDNA represents the genomic DNA control. EF1-4α is used as a control to standardize the RT-PCR reactions. Right: CHLM protein accumulation in wild-type plants and homozygous mutants shown by immunoblot. B- Phenotype of the mutant. Aspect of seedlings from seeds of heterozygous plants, grown for 6 d at 10 μmol photons m−2 s−1. On the right, the magnification shows a mutant plant grown for 5 d at 70 μmol photon m−2 s−1, then for 15 d at 5 μmol photons m−2 s−1. At the bottom is a picture of a green silique from a heterozygous plant. C- Phenotype, genotype determination and analysis of CHLM protein accumulation in wild-type, homozygous and complemented plants. Top: picture of 12 day-old wild-type plant (left), chlm homozygous mutant (middle) and chlm homozygous mutant harboring a 35S CaMV promoter-CHLM cDNA construct (right). Middle: PCR analysis of the genomic DNA from plants represented on the top picture using primers to detect the endogenous CHLM gene and the transgene cDNA or the T-DNA. Bottom: Immunoblot on total proteins from plants represented on the top picture using an anti-CHLM antibody.

Since the yellow/white plants could not produced seeds, homozygous mutants were only obtained from heterozygous plants. During silique maturation, some white seeds were visible suggesting absence of chlorophyll in the cotyledons of the homozygous seeds (Fig. 1B). However after desiccation, the seed color heterogeneity was no longer visible, making it impossible to visualize the mutant at this stage. When germinated on MS-agar containing 0.5% sucrose and under medium light (70 μmol photons m−2 s−1), the homozygous seedlings turned white and stopped growth after cotyledon development. However, when the plants were transferred after 5 d in medium light to dim light (5 μmol photons m−2 s−1), they could develop, although very slowly and with a stunted appearance; they then formed small yellow leaves (Fig. 1B). The absence of chlorophyll in the yellow homozygous plants was verified by spectrophotometry (Fig. 2A). Complementation of the mutant with the CHLM cDNA sequence resulted in expression of the CHLM protein and restoration of the green phenotype (Fig. 1C). Altogether, these results indicate that this chlm mutant is an Mg protoporphyrin IX methyltransferase null mutant and that the CHLM gene plays a unique role in the chlorophyll biosynthetic pathway in higher plants.

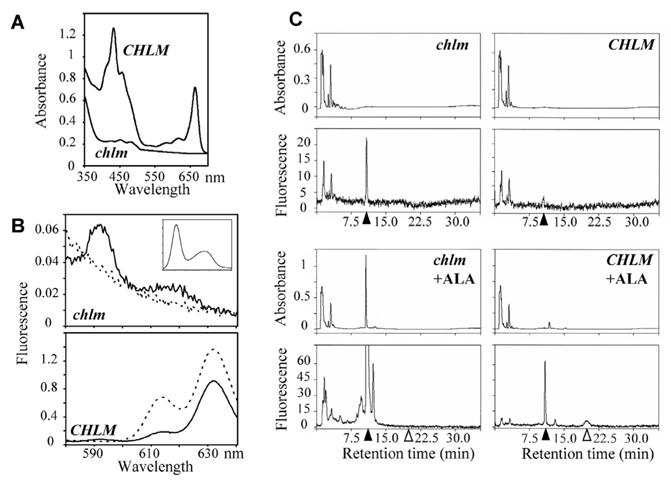

Figure 2. Analysis of pigments and chlorophyll precursors in the chlm mutant.

A- Absorbance spectra of pigments extracted from the mutant (solid line) and wild type/heterozygous plants (dotted line). B- Room temperature fluorescence emission spectra of acetone extracts of mutant and wild type/heterozygous plants. The plain line indicates emission obtained with excitation light at 402 nm and the broken line at 440 nm. Plants were grown for 10 d with a 10 h light cycle at 70 μmol photons m−2 s−1. The insert indicates fluorescence emission of standard Mg protoporphyrin IX with excitation light at 402 nm. C-HPLC traces of the acetone extracts of mutant and wild type/heterozygous plants. Plants were grown for 5 d at 70 μmol photon m−2 s−1, then for 15 d at 5 μmol photons m−2 s−1. 20 to 50 mg leaves + cotyledons were extracted. The eluate was monitored by absorbance at 420 nm (top) and by fluorescence emission at 590 nm with excitation set at 420 nm (bottom) for more specific detection of Mg protoporphyrin IX and Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester. Products were identified by concordance with retention times of standard compounds; closed and open arrows indicate position of Mg protoporphyrin IX and Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester, respectively. In +ALA conditions, plants were incubated overnight with 10 mM ALA and 5 mM MgCl2 in 10 mM Hepes pH 7.0 before extraction.

Accumulation of Mg protoporphyrin IX

Fluorescence analysis and HPLC separation of acetone extracts showed that Mg protoporphyrin IX was the main chlorophyll intermediate present in the mutant (Fig. 2B and 2C). When the mutant was fed with ALA to increase the synthesis of intermediates, we observed an increase of Mg protoporphyrin IX whereas Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester and other downstream chlorophyll intermediates were absent (Fig. 2C). Conversely, in the wild type, fluorescent spectra indicated the presence of downstream chlorophyll intermediates and Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester was detected by HPLC when the wild type was fed with ALA. Altogether the data indicated that in the chlm mutant, the chlorophyll pathway is indeed blocked in the methyltransferase step leading to accumulation of Mg protoporphyrin IX.

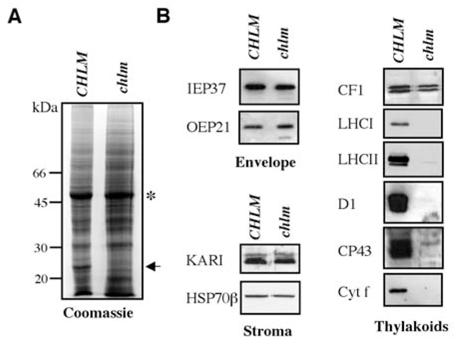

Absence of chlorophyll containing protein complexes in the chlm mutant

To evaluate chloroplast development in the mutant, we analyzed the expression of a series of proteins in leaves of plants grown 20 days in medium/dim light conditions. After SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining, we observed that the profiles of total protein extracts from wild type and mutant were similar (Fig. 3A). The large subunit of Rubisco was apparently present at a similar level in both types of plants. However a major difference was visible at the molecular size expected for LHCII proteins (Fig. 3A, arrow). Immunoblot detection confirmed considerable reduction in the accumulation of a number of major thylakoid-associated proteins including components of photosystem I (LHCI), photosystem II (LHCII, D1, CP43) and the Cytochrome b6f-complex (Cytf) (Fig. 3B). In contrast, no significant change was visible in the levels of stromal proteins KARI and HSP70β, chloroplast envelope proteins IE37 and OEP21, or thylakoid protein CF1 from CF1-CF0 ATPase (Fig. 3B). The chlm null mutant was therefore devoid of the major chlorophyll-containing protein complexes.

Figure 3. Analysis of protein accumulation in the chlm mutant.

A- Proteins extracted from leaves of wild type/heterozygous (CHLM) or chlm mutant (chlm) plants grown for 5 d at 70 μmol photon m−2 s−1 before 15 d at 5 μmol photons m−2 s−1, were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained by Coomassie blue. The arrow indicates the position of LHCII and the asterisk the position of RubiscoL. B- Immunoblot analysis of wild type/heterozygous and homozygous mutant plant proteins. The protein against which the antibody is directed is indicated on the left. The plastidial localization of the tested proteins is indicated at the bottom of each panel.

The chlm mutant behaves as a “super represser” of nuclear photosynthesis genes

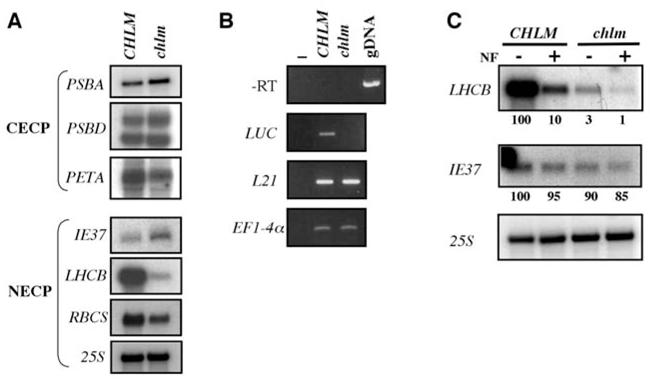

Several processes can induce depletion in chlorophyll-containing proteins, from gene expression to protein turn over. Northern blot analysis indicated that very little change was observed for the expression of chloroplast genes PSBA, PSBD and PETA while the corresponding proteins (D1, CP43 and Cytf) were absent (compare Fig. 3B and Fig. 4A, top). This result confirms that the accumulation of plastid-encoded chloroplast proteins is mostly regulated at a translational or posttranslational level.

Figure 4. Analysis of plastidial protein encoding gene expression in the chlm mutant.

A- Northern blot analysis of RNA extracted from wild type/heterozygous (CHLM) and homozygous mutant (chlm) plants. Genes encoding chloroplast-encoded chloroplast proteins (CECP) have been tested in the top panel and are indicated on the left. Genes encoding nucleus-encoded chloroplast proteins (NECP) have been tested in the bottom panel and are indicated on the left. B- RT-PCR analysis of RNA extracted from segregating wild type/heterozygous (CHLM) and homozygous mutant (chlm) plants harboring the LHCII promoter-luciferase fusion. Specific primers have been used to analyse luciferase (LUC) expression. The absence of genomic DNA contamination is indicated by the -RT panel, using L21 primers. The standardization has been done using both L21 and EFl-4α specific primers. C- Northern blot analysis of RNA extracted from wild type/heterozygous (CHLM) and homozygous mutant (chlm) plants grown in the absence or in the presence of Norfluorazon (NF). The probes used are indicated on the left and figures below each panel indicate relative quantification of the signals.

In contrast, the levels of LHCB transcripts and, to a lesser extent, RBCS transcripts, were reduced in the chlm mutant whereas the levels of mRNA for the chloroplast inner envelope protein IE37 (33) and of 25S cytosolic ribosomal RNA were not affected (Fig. 4A, bottom). In order to verify that the low amount of LHCB mRNA in the chlm mutant was related to transcriptional repression, we crossed a heterozygous CHLM/chlm plant with a line harboring an LHCB promoter-Luciferase construct and compared the LHCB promoter-dependent expression of the luciferase reporter gene in the wild-type and chlm mutant backgrounds. We observed no luciferase mRNA in the chlm mutant (Fig. 4B), indicating that the decrease of LHCB mRNA accumulation in the mutant is due to transcriptional repression.

Moreover, in an assay for the gun (genome uncoupled) phenotype as defined by (22), we compared LHCB mRNA accumulation in wild-type and chlm mutant plants grown either in the absence or in the presence of Norfluorazon (Fig. 4C). We observed that photobleaching by Norflurazon induced even stronger repression of the LHCB gene in the chlm mutant compared to the wild-type, indicating that this mutant does not show a gun phenotype (compare Fig. 4C, lanes 2 and 4). This is not surprising since this mutant is expected to accumulate greater amounts of Mg protoporphyrin IX through a direct effect on the biosynthetic pathway. Interestingly, the extent of repression observed in the chlm mutant in the absence of Norflurazon is even stronger than that observed in wild-type plants treated with Norfluorazon. This indicates that the chlm mutant behaves more like a “super represser” of LHCB gene expression. In conclusion, in the chlm null mutant, the chloroplast-to-nucleus retrograde signaling seems to be turned on without any additional treatment.

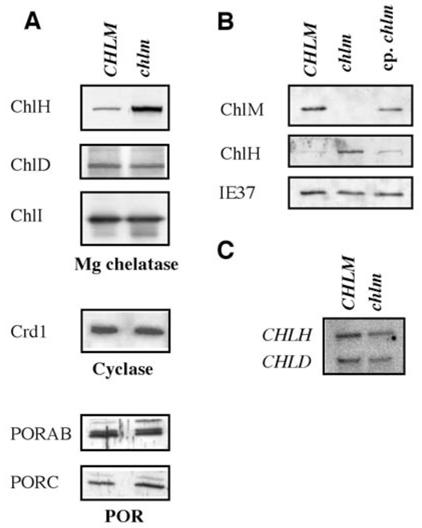

Up-regulation of CHLH

Besides the role of Mg protoporphyrin IX in the plastid-to-nucleus signaling pathway, published data suggests an additional role for certain enzymes in the chlorophyll synthesis pathway, such as the Mg chelatase subunits (20). We analyzed how these proteins are affected in the chlm mutant. Immunoblot analysis showed that the CHLD and CHLI subunits of the Mg chelatase, the CRD1 subunit of the cyclase and the POR proteins are present in similar amounts, whereas the CHLH Mg chelatase subunit is 5 to 8 times more abundant in the mutant than in the wild-type (Fig. 5 A). In the chlm complemented mutant, the level of CHLH protein is reduced, although not quite to the wild-type level (Fig. 5B), indicating that CHLM depletion leads to a specific increase in the level of the CHLH subunit of the Mg chelatase. Northern blot analyses indicated that, in the chlm mutant compared to the wild type, there were similar or barely lower levels of CHLH and CHLD transcripts (Fig. 5C). Therefore, the up-regulation of the CHLH subunit occurs at a post-transcriptional level in the chlm mutant.

Figure 5. Analysis of the expression of proteins from the chlorophyll biosynthesis pathway in the chlm mutant.

A- Immunoblot analysis of wild type/heterozygous (CHLM) and homozygous mutant (chlm) plant proteins. The protein against which the antibody is directed is indicated on the left. B- Immunoblot analysis of wild type/heterozygous (CHLM), homozygous mutant (chlm) and complemented homozygous mutant (cp. chlm) plant proteins. The protein against which the antibody is directed is indicated on the left. C- Northern blot analysis of RNA extracted from wild type/heterozygous (CHLM) and homozygous mutant (chlm) plants. Probes against the CHLH and CHLD genes were used and are indicated on the left.

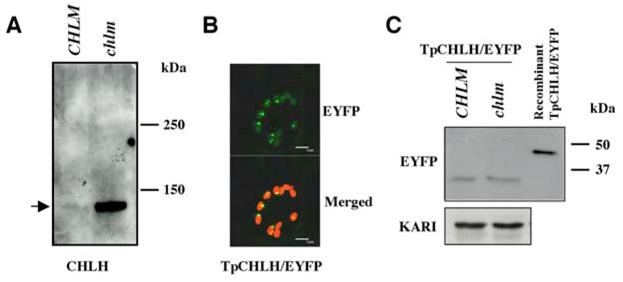

CHLH is matured and accumulates inside plastids

As an initial step to elucidate the regulatory mechanism leading to this accumulation, we checked if CHLH is located inside and/or outside plastids in the chlm mutant. Since isolation of plastids from these plants was not possible, we indirectly addressed this question by testing for the presence of a unprocessed CHLH precursor in the chlm mutant. The precursor protein was expected at 154 kDa and the mature protein at 144 kDa. When running on a high molecular weight resolving gel, CHLH was visualized around 144 kDa, clearly below the 150 kDa marker and the size of the protein was similar in both the wild type and the mutant, suggesting that most of the CHLH protein, if not all, is matured and most probably addressed to plastids.

The accumulation of processed CHLH protein in the chlm mutant could be related either to an increased stability of the protein in the chlm plastids or a more efficient import of the precursor form into chlm plastids. To verify the capability of the CHLH transit peptide for sorting the protein to chloroplasts, we expressed this peptide fused to the N-terminal end of EYFP in wild-type and chlm plants and analyzed the localization of the fusion protein. In the wild-type, EYFP and chlorophyll fluorescence colocalized indicating a chloroplast targeting of the EYFP protein. Aggregation of part of the EYFP in the chloroplasts is likely because additional highly fluorescent spots of EYFP were visible in the chlorophyll fluorescence area (Fig. 6B). In the chlm mutant where chlorophyll is absent, the same image of EYFP fluorescence was observed, suggesting the same plastid localization (Data not shown). To discriminate between an increased stability of CHLH or a more efficient import into chlm plastids, we compared the accumulation of the EYFP fusion protein in CHLH transit peptide-EYFP transgenic plants cosegregating for the chlm T-DNA (Fig. 6C). The size of the EYFP fusion protein in each plant was similar and corresponded to EYFP without the transit peptide and its accumulation was not different. Our conclusion is that the CHLH transit peptide is still capable of addressing the precursor protein into chloroplasts even in the chlm mutant context and that its import capacity is not modified in the chlm mutant. Therefore, the accumulation of the CHLH protein in the chlm mutant probably occurs at a post-translocational level.

Figure 6. Analysis of the CHLH protein in the chlm mutant.

A- Wild type/heterozygous (CHLM) and homozygous mutant (chlm) plant proteins were run on a high molecular weight resolving gel and analyzed with an anti-CHLH antibody. B- Confocal microscopy analysis of wild type seedlings harboring the CHLH transit peptide-EYFP fusion (TpCHLH/EYFP). The EYFP fluorescence picture is shown at the top and merging between this picture and a chlorophyll fluorescence picture at the bottom. The bar corresponds to 5 μm. C- Immunoblot analysis of proteins from segregating wild type/heterozygous (CHLM) and homozygous mutant (chlm) plants harboring the CHLH transit peptide-EYFP fusion. The recombinant CHLH transit peptide-EYFP protein produced in E. coli has been used as a size control. An anti-KARI antibody was used to calibrate loading.

DISCUSSION

CHLM is a key gene for chlorophyll biosynthesis and chloroplast development. Our results show that chlorophyll formation is totally dependent on the CHLM gene product in Arabidopsis. The inactivation of this gene prevents setting up of chlorophyll binding proteins in the thylakoids whereas most other proteins in the chloroplast remain relatively stable. Not only photosystem I and II with their associated light harvesting complex are affected but also the cytb6f complex that contains very low amounts of chlorophyll (34–36). Chlorophyll is required for maturation of chlorophyll binding proteins, for correct folding of the complexes and for their insertion in the thylakoids (for a review 1). It also has a stabilizing effect on complexes, complexes lacking chlorophyll proteins becoming substrates for proteases. This was reported for chloroplast encoded proteins such as D1, CP43 and Cyt f (37) and it may explain the absence of these proteins in the mutant since we effectively observed that the corresponding mRNAs were expressed at relatively normal levels.

Modification of expression of nuclear encoded photosynthetic genes

On the opposite, the level of LHCB mRNAs is greatly decreased in the mutant, due to transcriptional regulation. Since the mutant specifically accumulates Mg protoporphyrin IX without any treatment, our result provides an independent indication that Mg protoporphyrin IX is a negative effector of nuclear photosynthetic gene expression, as previously suggested in Norfluorazon treated plants (19). Moreover, the chlm mutant behaves like a super-repressor of the LHCB promoter and seems more efficient in repressing LHCB expression than plants treated with Norflurazon. The extent of repression may be due to a different level of accumulation of Mg protoporphyrin IX in the plant. A second possibility may be linked to the complete absence of Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester and its derivatives in the mutant. This suggests that one of these components acts as a positive effector of nuclear photosynthetic gene expression. Mg protoporphyrin methylester itself may be a positive effector. In support of this latter hypothesis, (24) have shown that, in the absence of Norflurazon, the barley xantha l mutant that is defective in the Mg protoporphyrin methylester cyclase, accumulates Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester and has a high level of LHCB expression. In addition, (8) reported positive correlation between LHCB expression and methyltransferase activity in tobacco CHLM antisense and sense RNA mutants.

The activity of Mg protoporphyrin IX methyltransferase is obviously dependent on the availability of Mg protoporphyrin IX but is also certainly adjusted to levels of Ado-Met and Ado-Hcy in the chloroplast (see for instance 38). The differential effects of Mg protoporphyrin IX and Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester on LHCB expression would consequently finely attune the synthesis of light harvesting complexes to the one-carbon metabolism.

Increase of CHLH level

In the chlm mutant we observed a strong increase in the level of mature CHLH, whereas that of CHLH mRNA was slightly reduced. Our data indicate that stabilization of the protein inside chloroplasts probably occurs in the chlm mutant. One possible mechanistic explanation for this accumulation could be traced to the increased level of Mg protoporphyrin IX in this mutant. Indeed, a tight channeling of substrate between the Mg chelatase and the methyltransferase has been suspected for a long time due to the absence of detectable Mg protoporphyrin intermediates in standard conditions (39). More recently, the physical interaction between CHLM and CHLH has been shown (40, 7). During diurnal growth, the Mg chelatase activity peaks during the transfer from dark to light while the methyltransferase activity maximum follows only a few hours later. During this period, the Mg protoporphyrin IX level is transiently higher than that of Mg protoporphyrin IX methylester (7). It is possible that Mg protophorphyrin IX binds to CHLH, preventing the transitory accumulation of free Mg protoporphyrin IX when CHLM is not sufficiently present/active. This could both stabilize the rapidly turning over CHLH protein (5) and protect it against major photooxidative damage generated by free Mg protoporphyrin IX. Whatever the mechanism underlying CHLH accumulation, one can question whether its concomitant increase with Mg protoporphyrin IX plays a role in mediating the plastid-to-nucleus regulatory pathway.

Acknowledgments

Particular thanks are due to researchers who gave us aliquots of antibodies we used in this work: R. Dumas, M. Schroda, S. Merchant, T. Masuda, F.-A. Wollman and M. Hansson. We acknowledge D. Vega for excellent technical assistance and F.-Y. Bouget for the LHCII-LUC line. We thank Dr. R. Cooke for copy editing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Paulsen H. Advances in Phosynthesis and Respiration. In: Aro EM, Anderson B, editors. Regulation of Photosynthesis. 2001. pp. 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibson LC, Willows RD, Kannangara CG, von Wettstein D, Hunter CN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1941–1944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willows RD, Gibson LC, Kanangara CG, Hunter CN, von Wettstein D. Eur J Biochem. 1996;235:438–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papenbrock J, Grafe S, Kruse E, Hanel F, Grimm B. Plant J. 1997;12:981–990. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.12050981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakayama M, Masuda T, Bando T, Yamagata H, Ohta H, Takamiya K. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998;39:275–284. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Block MA, Tewari AK, Albrieux C, Marechal E, Joyard J. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:240–248. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alawady A, Reski R, Yaronskaya E, Grimm B. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;57:679–691. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-1427-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alawady AE, Grimm B. Plant J. 2005;41:282–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pineau B, Gerard-Hirne C, Douce R, Joyard J. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:821–828. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.3.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matringe M, Camadro JM, Block MA, Joyard J, Scalla R, Labbe P, Douce R. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4646–4651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tottey S, Block MA, Allen M, Westergren T, Albrieux C, Scheller HV, Merchant S, Jensen PE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:16119–16124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136793100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joyard J, Block M, Pineau B, Albrieux C, Douce R. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:21820–21827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barthelemy X, Bouvier G, Radunz A, Docquier S, Schmid GH, Franck F. Photosynth Res. 2000;64:63–76. doi: 10.1023/A:1026576319029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White RA, Wolfe GR, Komine Y, Hoober JK. Photosynthesis Res. 1996;47:267–280. doi: 10.1007/BF02184287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoober JK, Eggink LL. Photosynthesis Res. 1999;61:197–215. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reinbothe C, Bartsch S, Eggink LL, Hoober JK, Brusslan J, Andrade Paz R, Monnet J, Reinbothe S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4777–4782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511066103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kropat J, Oster U, Rudiger W, Beck CF. Plant J. 2000;24:523–531. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayfield SP, Taylor WC. Eur J Biochem. 1984;144:79–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strand A, Asami T, Alonso J, Ecker JR, Chory J. Nature. 2003;421:79–83. doi: 10.1038/nature01204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mochizuki N, Brusslan JA, Larkin R, Nagatani A, Chory J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2053–2058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larkin RM, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Chory J. Science. 2003;299:902–906. doi: 10.1126/science.1079978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Susek RE, Ausubel FM, Chory J. Cell. 1993;74:787–799. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90459-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rzeznicka K, Walker CJ, Westergren T, Kannangara CG, von Wettstein D, Merchant S, Gough SP, Hansson M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5886–5891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501784102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gadjieva R, Axelsson E, Olsson U, Hansson M. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2005;43:901–908. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Millar AJ, Kay SA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:15491–15496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mittler R, Lam E. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1951–62. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.11.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moran R, Porath D. Plant Physiol. 1980;65:478–479. doi: 10.1104/pp.65.3.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurkman WJ, Tanaka CK. Plant Physiol. 1986;81:802–806. doi: 10.1104/pp.81.3.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagy F, Boutry M, Hsu MY, Wong M, Chua NH. EMBO J. 1987;6:2537–42. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Logemann J, Mayer JE, Schell J, Willmitzer L. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:1136–1140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bechtold N, Ellis J, Pelletier G. CR Acad Sci Paris Life Sc. 1993;316:1194–1199. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samson F, Brunaud V, Balzergue S, Dubreucq B, Lepiniec L, Pelletier G, Caboche M, Lecharny A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:94–97. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Block MA, Dorne AJ, Joyard J, Douce R. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:13281–13286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jordan P, Fromme P, Witt HT, Klukas O, Saenger W, Krauss N. Nature. 2001;411:909–917. doi: 10.1038/35082000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zouni A, Witt HT, Kern J, Fromme P, Krauss N, Saenger W, Orth P. Nature. 2001;409:739–743. doi: 10.1038/35055589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pierre Y, Chabaud E, Herve P, Zito F, Popot JL. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1031–1041. doi: 10.1021/bi026934c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eichacker LA, Helfrich M, Rudiger W, Muller B. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32174–32179. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravanel S, Block MA, Rippert P, Jabrin S, Curien G, Rebeille F, Douce R. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22548–22557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorchein A. Biochem J. 1972;127:97–106. doi: 10.1042/bj1270097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hinchigeri SB, Hundle B, Richards WR. FEBS Lett. 1997;407:337–342. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]