Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a common, medically relevant human herpesvirus. The tegument layer of herpesvirus virions lies between the genome-containing capsids and the viral envelope. Proteins within the tegument layer of herpesviruses are released into the cell upon entry when the viral envelope fuses with the cell membrane. These proteins are fully formed and active and control viral entry, gene expression, and immune evasion. Most tegument proteins accumulate to high levels during later stages of infection, when they direct the assembly and egress of progeny virions. Thus, viral tegument proteins play critical roles at the very earliest and very last steps of the HCMV lytic replication cycle. This review summarizes HCMV tegument composition and structure as well as the known and speculated functions of viral tegument proteins. Important directions for future investigation and the challenges that lie ahead are identified and discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a successful, widespread pathogen that infects the majority of the world's population by early adulthood (126). The virus establishes a life-long infection with a reservoir of both latently infected cells and persistently infected cells that intermittently shed infectious virus. Numerous cell types become infected, and virus can be found in most organ systems (169). HCMV infection is responsible for approximately 8% of the cases of infectious mononucleosis, and in populations with immature or compromised immune systems, HCMV is a significant pathogen causing morbidity and mortality (178). It is the leading viral cause of birth defects (57), where infection of neonates causes deafness and mental retardation, and is the major cause of retinitis and blindness in AIDS patients. HCMV contributes to graft loss in bone marrow and solid-organ transplants, causes disease in cancer patients receiving immunosuppressive chemotherapy, and likely contributes to ageing-associated immunosenescence (94, 180). HCMV infection is also associated with inflammatory and proliferative diseases such as certain cardiovascular diseases and some cancers (172). Both primary infection and reactivation of latent infections cause HCMV disease. There is no vaccine to prevent HCMV infection, and the drugs currently approved by the FDA for the treatment of HCMV disease suffer from low bioavailability, toxicity, and the formation of resistant viruses (18).

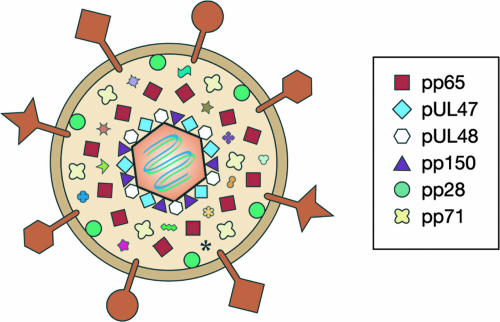

HCMV is the prototype member of the betaherpesvirus family and has the classical herpesvirus structure and cascade of gene expression (126). The virion (Fig. 1) is composed of the double-stranded, 235-kb DNA genome enclosed in an icosahedral protein capsid, which itself is surrounded by a proteinaceous layer termed the tegument (the topic of this review) and, finally, a lipid envelope. The genome is divided by internal repeat sequences (IRS) into segments termed the unique long (UL) and unique short (US) regions. Terminal repeat sequences (TRS) are also present. Viral genes (of which there are more than 166) are named with a prefix based upon the segment of the genome in which they are located and are numbered sequentially. Virally encoded glycoproteins in the envelope function as mediators of viral entry through a membrane fusion event, which releases both the DNA-containing capsid and the tegument proteins into the cell. The expression of viral immediate-early (IE) genes commits the virus to the lytic replication program. Viral IE proteins modulate the host cell environment and stimulate the expression of viral early genes. Viral early proteins replicate viral genomic DNA. After DNA replication, viral late genes are expressed. The late proteins are mostly structural components of the virion and permit the assembly and egress of newly formed progeny viral particles. In certain cell types, IE genes are silenced upon HCMV infection, resulting in a latent infection (168). During latency, viral gene expression is minimized, presumably to avoid immune detection, and no viral progeny are produced. Latent infections periodically reactivate as productive, lytic infections that cause disease and allow viral spread.

FIG. 1.

The HCMV virion. The cartoon represents (not to scale) an average HCMV infectious viral particle. Abundant tegument proteins are listed. The large shapes on the surface of the virion represent various virally encoded membrane glycoproteins. Please see the text for further details.

In addition to infectious virions, two other types of particles, noninfectious enveloped particles (NIEPS) and dense bodies, are also produced from HCMV-infected cells (70). NIEPS are very similar to infectious virions and contain an essentially identical assortment of envelope, tegument, and capsid proteins but lack viral genomes packaged within the icosahedral capsid. Dense bodies are enveloped tegument proteins that lack capsids (and thus genomes). They are composed primarily of the viral pp65 protein (see below). The significance (if any) of these two types of particles to HCMV infections is not well understood.

Activities for less than half of the tegument proteins have been determined or suggested (Table 1). The phenotypes of recombinant viruses with null mutations in genes encoding tegument proteins demonstrate that some are absolutely essential for viral replication, others are required for efficient replication (often termed augmenting genes), while still others are dispensable for lytic replication in vitro (44, 126, 209). This review discusses the functional roles that tegument proteins play during HCMV infection, which include early events such as the delivery of viral genomes to the nucleus, the regulation of gene expression, and disarming the immune system as well as later events such as the assembly of viral particles and their release from the infected cell.

TABLE 1.

HCMV tegument proteinsa

| Gene (protein) | Phenotype | Function(s) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| UL23 | D | ||

| UL24 | D | ||

| UL25 | D | Colocalizes with pp28 | 12 |

| UL26 | A | Increases stability of virion proteins | 108,127 |

| UL32 (pp150) | E | Directs capsid to site of final envelopment | 7 |

| UL35 | A | Activates viral gene expression | 162 |

| UL36 | D | Inhibits apoptosis | 171 |

| UL38 | A | Inhibits apoptosis | 186 |

| UL43 | D | ||

| UL44 | E | HCMV DNA polymerase processivity/transcription factor | 74 |

| UL45 | A | Inactive (?) ribonucleotide reductase subunit | 135 |

| UL47 | A | Release of viral DNA from capsid | 14 |

| UL48 | E | Deubiquitinating protease | 194 |

| Release of viral DNA from capsid | 14 | ||

| UL50 | E | Nuclear egress of capsids | 148 |

| UL53 | E | Nuclear egress or assembly of capsids | 39 |

| UL54 | E | Viral DNA polymerase | 63,95 |

| UL57 | E | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein | 89 |

| UL69 | A | Nuclear export of unspliced mRNAs | 103 |

| Arrests cell cycle in G1 phase | 109 | ||

| UL71 | A/E | ||

| UL72 | A | Inactive (?) dUTPase | 30 |

| UL76 | A/E | Nuclear function? | 196 |

| UL77 | E | Putative pyruvoyl decarboxylase | 208 |

| UL79 | E | ||

| UL82 (pp71) | A | Degrades Daxx; facilitates IE gene expression | 152 |

| Degrades Rb; stimulates cell cycle progression | 81 | ||

| Prevents cell surface expression of MHC | 189 | ||

| UL83 (pp65) | D | Endogenous kinase activity | 207 |

| Associated kinase activity | 47,85 | ||

| Evasion of adaptive immunity | 52 | ||

| Evasion of innate immunity | 6 | ||

| UL84 | E | HCMV DNA replication/transcription factor | 48 |

| UL88 | D | ||

| UL93 | E | ||

| UL94 | A/E | Putative DNA-binding protein | 200 |

| Similar to autoantigen in systemic sclerosis | 110 | ||

| UL96 | A/E | ||

| UL97 | A | Kinase that phosphorylates ganciclovir | 105,181 |

| Stimulates DNA replication, assembly/egress | 139 | ||

| Cyclin-dependent kinase-like functions | 67 | ||

| Disrupts nuclear aggresomes | 141 | ||

| UL99 (pp28) | E | Directs enclosure of enveloped particles | 166 |

| UL103 | A | ||

| UL112 | A | HCMV DNA replication factor | 134 |

| IRS1/TRS1 | A/E | Inhibits PKR antiviral response | 61 |

| Virion assembly | 3 | ||

| US22 | D | 2 | |

| US23 | A | ||

| US24 | A | Activates viral gene expression | 46 |

Genes that encode tegument proteins along with commonly accepted protein names (if applicable) are shown. Phenotypes are listed as augmenting (A), dispensable (D), or essential (E) and refer to the requirement of the gene for lytic replication in human fibroblast cells in vitro as determined either in the provided reference, by two global mutational analyses of HCMV (44, 209), or as described in a recent review (126). The column labeled “Function(s)” displays either demonstrated or inferred functions for these proteins. Blank rows indicate that no function has been described or hypothesized. Envelope glycoproteins and capsid components are not included.

TEGUMENT COMPOSITION AND STRUCTURE

The tegument layer of HCMV virions (84, 126) is defined as the space enclosed by the lipid envelope but outside of the protein capsid. Visualization of herpesvirus virions by electron microscopy and electron tomography has shown that the tegument is generally unstructured or amorphous (34, 58, 190), although some structuring of tegument proteins closely associated with the capsid has been observed. Of the 71 viral proteins found within infectious virions (192), over one-half (Table 1) appear to be tegument components (the others are capsid or envelope proteins). Tegument protein abundance can be inferred (although not precisely determined) by comparing their signal intensities observed during proteomic analysis of virions to the signal of the major capsid protein, which is known to exist at 960 copies (triangulation number = 16) per virion (27). Thus, while abundances for some tegument proteins are listed in this review, they should be considered to be estimates. In general, viral tegument proteins are phosphorylated (and are thus sometimes named with the prefix pp, for phosphoprotein), but the significance of phosphorylation to their function remains largely unexamined. Neither experimental nor bioinformatic approaches have identified a common sequence that can specifically direct proteins into the tegument (analogous to a nuclear localization signal). It is likely that phosphorylation, subcellular localization to the assembly site, interaction with capsids or the cytoplasmic tails of envelope proteins, as well as the formation of higher-order heterologous complexes all facilitate the incorporation of proteins into the HCMV tegument. Thus, the mechanisms through which tegument proteins are incorporated into virions remain an enigma while continuing to be an area of active research. In the absence of any discovered common mode of virion incorporation for tegument proteins, a determination of the incorporation requirements for multiple individual viral proteins seems to be a logical approach to solving the puzzle of tegument assembly.

In addition to viral proteins, approximately 70 cellular proteins have been found in the HCMV virion (192), presumably in the tegument layer. Specific roles for any of these cellular tegument proteins have not been extensively examined. Furthermore, viral and cellular RNAs are also packaged within virions, NIEPS, and dense bodies, presumably in the tegument layer (185). RNA packaging is proportional to the expression level, does not appear to require a specific signal, and may occur by nonspecific interactions with tegument proteins (185). These RNAs may be incorporated for structural stability in order for their translation in a newly infected cell or simply nonspecifically. More work is required to determine the role that virion RNAs play during HCMV infections.

ENTRY

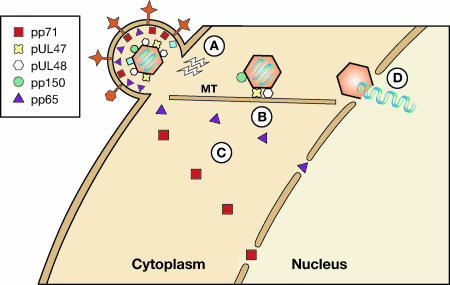

Upon interaction of the viral envelope glycoproteins with cellular receptors on fibroblasts, the virion and cell membranes fuse (37), releasing the capsid and tegument proteins directly into the cytoplasm. In epithelial and endothelial cells, HCMV enters through low-pH-dependent endocytosis mediated by additional viral envelope glycoproteins (151). Any roles that tegument proteins may play in the process of membrane fusion during viral entry remain largely unexamined. After fusion, some tegument proteins likely remain in the cytoplasm. Others, such as pp65 and pp71, appear to migrate independently to the nucleus. Still other tegument proteins remain tightly associated with the capsid and mediate the delivery of capsids along microtubules to the nuclear pore complex, through which the viral genomic DNA then enters the nucleus (Fig. 2). The processes of HCMV entry and capsid delivery to the nucleus have been recently reviewed (71, 84). The tegument proteins suspected to play roles in the delivery of incoming viral genomes to the nucleus are described below.

FIG. 2.

Tegument proteins help deliver the HCMV genome-containing capsid to the nucleus during the viral entry process. (A) Signals initiated upon receptor binding induce cellular antiviral responses but may also prime the cell for subsequent events during viral entry. (B) Capsid-associated tegument proteins UL47 and UL48 (and perhaps pp150) direct capsids along microtubules (MTs) toward nuclear pore complexes. Cellular motor proteins such as dynein (not shown) likely assist this transport. (C) A subset of tegument proteins (such as pp65 and pp71) is transported to the nucleus independently of capsids. (D) Capsids eventually dissociate from microtubules, dock at nuclear pores, and release their DNA into the nucleus. The role of tegument proteins in this process is implicated but has not been described in detail.

pUL47 (HMWP-Binding Protein)

Disruption of the UL47 gene, which is expressed with late kinetics (69), results in a 100-fold reduction in viral titers after infections at either high or low multiplicities (14). The UL47 protein is found in approximately equal levels in infectious virions, NIEPS, and dense bodies (9). A proteomic analysis of purified virions estimated that at least 240 copies of UL47 are packaged into an average virion (192). UL47 binds to the high-molecular-weight protein (HMWP) (UL48) (see below) and, thus, has been called HMWP-binding protein (194). In addition to binding UL48, UL47 also interacts with the UL69 tegument protein and with the major capsid protein, perhaps forming a complex (14). Interestingly, the absence of UL47 results in a decrease in the accumulation of the UL48 protein (but apparently not the mRNA from which it is translated) and a decrease in UL48 incorporation into virions (14). This indicates that UL47 is required for either the efficient translation of or, more likely, the stability of UL48. Thus, the UL47-null virus is also deficient in UL48, making it difficult to ascribe a specific function to UL47. Upon infection of permissive fibroblasts with a UL47-null virus, viral IE gene expression is delayed, but entry, as assayed by the delivery of the tegument proteins pp65 and pp71 to the nucleus, appears to be normal (14). These data, along with the phenotype of a herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) temperature-sensitive mutant in the homolog of UL48 (11), led to the hypothesis that a UL47-containing complex facilitates the efficient release of viral DNA from the capsid (14). However, because the levels of IE mRNA eventually accumulate to near-wild-type levels but the titers of the mutant virus never approach that of the wild type, UL47 and/or UL48 likely plays an additional and as-yet-uncharacterized role or roles in HCMV infection, perhaps during viral maturation and/or egress (see below).

pUL48 (HMWP)

The UL48 gene has been classified as being either augmenting (209) or essential (44) and is expressed simultaneously as a 3′-coterminal transcript with UL47 (14, 69). Originally termed the HMWP, its incorporation into virions was known prior to establishing that it was the product of the UL48 gene (20, 50). It is also found in NIEPS and dense bodies (9) and is incorporated at approximately 1,400 copies per virion (192).

UL48 is a deubiquitinating protease (194), but the significance of this enzymatic activity for the viral life cycle has yet to be elucidated. One possible role for the deubiquitinating activity of UL48 is to inhibit the proteasomal degradation of viral proteins upon entry, thereby allowing them to exert their individual effects on the newly infected cells as well as to prevent their presentation to the immune system. The presence of such an enzymatic activity in virions may explain why the proteasomal degradation of repressive cellular transcription factors (81, 152) mediated by the tegument-delivered viral pp71 protein (see below) occurs through an unusual, ubiquitin-independent pathway (68, 83). Another possible role for the deubiquitinating activity of UL48 may be to facilitate viral egress. Recombinant HCMV with an active-site mutation in UL48 is viable but shows a temporal delay in virion release (194). As retroviral budding through the multivesicular body pathway has recently been shown to be inhibited by a catalytically inactive cellular deubiquitinating enzyme in a dominant fashion (4), the deubiquitinase activity of UL48 may also play a role during HCMV egress. Interestingly, an association between UL48 and a cellular protein that may participate in vesicular transport has been observed, but the role that this association plays during HMCV infection has not been analyzed (132).

Summary

The process of HCMV tegument disassembly upon viral entry is poorly understood. It is widely speculated that herpesvirus tegument proteins mediate the delivery of genome-containing capsids to the nuclear pore complex and perhaps the release of the viral DNA into the nucleus. In the alphaherpesviruses, there is accumulating evidence that the homologs of HCMV UL47 and UL48 (termed UL37 and UL36 [VP1/2], respectively) do indeed interact with each other and with capsids (36, 93, 193) and help transport those capsids along microtubules to the nucleus (112, 205). Further evidence that the HCMV UL47/UL48 complex may be analogous to the alphaherpesvirus UL37/UL36 complex is the similar phenotypes of HCMV UL47 and HSV-1 UL36 mutants described above as well as the observations that HSV-1 UL36 is also a deubiquitinating protease that appears to play a role in viral egress (43, 87). Thus, one can build a model in which a tight association of the HCMV UL47 and UL48 proteins with viral capsids and perhaps with microtubule motor proteins facilitates the delivery of capsids to the nuclear pore complex and perhaps the deposition of viral DNA into the nucleus. The approximately 5- to 10-fold decrease in the levels of UL47 and UL48 in dense bodies (9, 192) further suggests that these proteins are predominantly capsid bound. The HCMV pp150 protein also appears to be tightly associated with incoming capsids (170) and may thus play a role during viral entry (Fig. 2). Both genetic and biochemical experiments to test this model are warranted.

GENE EXPRESSION

After the delivery of the viral genome to the nucleus, viral IE genes are either expressed to initiate a lytic infection or repressed to establish latency. The pp71 protein is the only tegument component that plays a key and undisputed role in activating IE gene expression at the start of a lytic infection. Other tegument proteins may also increase viral gene expression; however, the significance of their contribution to this process is unclear, largely because viral mutants have not yet been fully analyzed.

pp71 (UL82)

Originally termed VP8 because it was identified as the eighth largest viral protein (160) and subsequently termed the upper matrix protein (145), the product of the UL82 gene (33) is most commonly referred to as pp71 (130). As its name implies, pp71 is a 71-kDa phosphoprotein (70) whose gene is located next to and shares homology with the UL83 gene encoding pp65 (33, 130, 149). The UL82 gene is expressed with early-late kinetics, and the pp71 protein localizes to the nucleus in both HCMV-infected and UL82-transfected cells (65).

The ability of HCMV virion proteins to activate expression from the viral major IE promoter (MIEP) was previously established (175, 179) when a candidate approach identified pp71 as being the first known HCMV virion transactivator (106). Subsequent work showed that pp71 increased the infectivity of transfected viral genomic DNA (10), as was previously shown for the virion transactivators encoded by alphaherpesviruses. This phenomenon is of increasing importance, as mutant viral genomes are now routinely generated in Escherichia coli cells as part of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones and must be transfected into permissive cells to reconstitute infectious virus (150). Interestingly, the preexpression of viral IE genes did not increase the infectivity of transfected viral genomic DNA (10), leading to the hypothesis that tegument-delivered pp71 facilitates viral replication by multiple methods, including the activation of viral IE gene expression. Genetic experiments described below subsequently confirmed this hypothesis.

Although pp71 is not absolutely essential, it is required for efficient viral replication. This was first proposed when it was observed that an antisense RNA to UL83 that would also hybridize to UL82 transcripts inhibited the expression of both pp65 (UL83) and pp71 (UL82) as well as viral replication (38) but that a deletion of UL83 alone had no effect on viral replication (163). A role for pp71 in HCMV replication was shown directly when a null mutant was constructed and found to have a severe growth defect (21). To isolate this mutant virus, a complementing cell line that expresses pp71 was employed, allowing the generation of two types of viral stocks. Null mutant viruses grown on complementing cells incorporate the ectopically expressed pp71 into the tegument and are called +/− viruses (present in virion/absent in genome) here. This is analogous to “pseudotyping” virions with exogenous glycoproteins. Null mutants passaged once at a high multiplicity of infection (MOI) in noncomplementing cells do not have pp71 in the tegument and are termed −/− viruses here. After low-MOI infections, both forms of pp71-null viruses (+/− and −/−) show a 10,000-fold growth defect (21). At higher multiplicities, the growth defect of the −/− virus is less severe (100-fold at an MOI of 3 and 5-fold at an MOI of 10) but still significant. Cells infected with pp71-null −/− stocks show decreased levels of expression of viral IE genes from at least four different loci: UL36-UL38, UL106-UL109, UL115-UL119, and the major IE locus UL122-UL123 (21). Interestingly, cells infected with the pp71-null +/− virus (with the pp71 protein in the tegument but missing the genomic copy of UL82) at a high MOI of 3 still showed a 10-fold growth defect (21). This may indicate that the “pseudotyped” pp71 did not completely rescue viral gene expression (which was not monitored in these experiments) or that pp71 plays an additional role in viral replication after its important role in stimulating IE gene expression, as previously speculated (9).

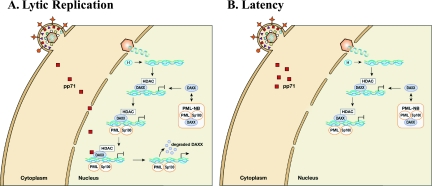

At least one mechanism through which pp71 activates viral gene expression is to counteract the repressive effects of the cellular Daxx protein (155). Daxx binds to histone deacetylases (HDACs) and is recruited to promoters by DNA-binding transcription factors, resulting in transcriptional repression. In addition, Daxx localizes to PML-nuclear bodies (PML-NBs), sites where other cellular transcriptional repressors also accumulate. pp71 binds to Daxx through two Daxx interaction domains (66) and partially localizes to PML-NBs through this interaction (66, 72, 116). Recombinant HCMVs expressing Daxx interaction domain mutant pp71 proteins (and not the wild type) that cannot bind Daxx have the same phenotype as the pp71-null mutant, indicating that pp71 binding to Daxx is required for efficient viral IE gene expression and subsequent replication (28). The molecular mechanism through which pp71 activates IE gene expression was identified when it was determined that pp71 induces the proteasomal degradation of Daxx to relieve Daxx- and HDAC-mediated silencing of the MIEP (152). Inhibition of Daxx degradation by a proteasome inhibitor (152) or the overexpression of Daxx (29, 206) inhibits IE gene expression in HCMV-infected cells and the knockdown of Daxx by RNA interference (29, 138, 152, 183, 206), or the inactivation of HDACs (152, 206) enhances IE gene expression in HCMV-infected cells, especially when pp71 activity is absent or inhibited. A model (Fig. 3A) for how pp71 regulates viral IE gene expression at the start of a productive, lytic infection was recently described (84).

FIG. 3.

Subcellular localization of tegument-delivered pp71 determines whether HCMV initiates lytic replication or establishes quiescent, latent-like infections. (A) Lytic replication initiates when tegument-delivered pp71 is allowed access to the nucleus. Capsids docked at nuclear pores release their DNA into the nucleus, and viral genomes associate with cellular histones (H). The Daxx protein, which rapidly dissociates from, and reassociates with, PML-NBs, accumulates around viral genomes, recruits an HDAC, and silences viral IE gene expression. Other PML-NB components are also recruited and participate in the silencing of viral genomes. pp71 binds to Daxx in these newly formed PML-NBs, induces Daxx degradation, derepresses viral IE gene expression, and thus initiates the lytic replication cycle. (B) In cells where quiescent or latent infections are established, tegument-delivered pp71 remains in the cytoplasm. Daxx (and presumably other PML-NB proteins) silences viral gene expression in these cells.

When latent HCMV infections are established, expression of the viral IE genes that initiate lytic replication is inhibited. In two independent in vitro models systems used to study the silencing of viral IE gene expression at the start of latent infections, a recent study found that Daxx is absolutely required to repress IE gene expression (153). When Daxx levels were reduced in these cells by RNA interference, viral IE genes were expressed, and lytic replication was initiated upon HCMV infection. However, lytic replication was not completed, but an abortive infection resulted. Thus, Daxx-mediated repression of viral IE gene expression may be utilized by the virus to prevent the initiation of lytic replication in cells that are not competent to support the complete, productive replication cycle (153).

Importantly, Daxx is not degraded in cells where latent infections are established because tegument-delivered pp71 fails to enter the nucleus but is trapped in the cytoplasm (153; R. T. Saffert and R. F. Kalejta, unpublished observations). Much like Daxx knockdown, the preexpression of nuclear pp71 in these cells allows IE gene expression and the initiation, but not the completion, of lytic replication. Thus, pp71 delivery to the nucleus and its subsequent degradation of Daxx appear to be the key events that determine whether lytic replication will be initiated or whether latency will be established (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the potential dual roles of PML-NB proteins such as Daxx in regulating herpesviral lytic and latent transcriptional programs are not confined to HCMV but also seem to be conserved in HSV-1 infections as well (154).

In addition to regulating viral IE gene expression, pp71 has additional activities. For example, pp71 targets the hypophosphorylated forms of the Rb family of tumor suppressors for proteasomal degradation (81). Similar to Daxx degradation (68), the pp71-mediated degradation of Rb proteins is proteasome dependent but ubiquitin independent (83). The hypophosphorylated forms of the Rb proteins bind to the E2F transcription factors and repress transcription from promoters that respond to E2F. Because E2F-responsive genes regulate DNA replication and progression into the S phase (41), it is suspected that it would be to the advantage of a DNA virus such as HCMV to inhibit Rb function and stimulate E2F activity. By degrading Rb proteins, pp71 does stimulate cell cycle progression by driving quiescent (G0) cells into the S phase (81). Interestingly, pp71 also appears to have an Rb-independent ability to accelerate cells through the G1 phase of the cell cycle (82). The functions that these activities of pp71 play during HCMV infection are unknown, but a mutant HCMV that expresses only a pp71 protein that is unable to degrade Rb (81) replicates as well as wild-type virus (28). Thus, although pp71 does mediate Rb degradation in HCMV-infected cells (67), such degradation is not essential for lytic viral replication in vitro. This is likely because in addition to pp71-mediated Rb degradation, HCMV has other ways to impact the Rb-E2F pathway (67, 174). Multiple redundant mechanisms attest to the importance of modulating this cellular pathway and make it challenging to decipher what roles the cell cycle regulatory functions of the individual proteins play during HCMV infection.

Finally, pp71 expression late during infection of semipermissive glioblastoma cells decreases the cell surface expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I proteins approximately 50% by slowing their intracellular transport (189). This activity of pp71 may be cell type dependent, as it was not observed in fully permissive fibroblasts (78). Much like the case for Rb/E2F described above, pp71 is only one of many HCMV proteins to modulate MHC class I proteins (125).

ppUL35

The UL35 open reading frame is transcribed into two coterminal transcripts that are translated from unique, in-frame start codons into two proteins (UL35 and UL35a) that are subsequently phosphorylated in infected cells (107). UL35 is considered to be the full-length protein (640 amino acids), while UL35a represents only the carboxy-terminal 193 amino acids of UL35 (107). Only the larger form of UL35 was found in the tegument of both virions and dense bodies. It localizes to the cytoplasm at the very start of a lytic infection in fibroblasts and accumulates to high levels only at late times of infection (107). The short form, UL35a, is synthesized with early-late kinetics and begins to accumulate in the nucleus of infected cells as early as 4 h postinfection (107). These same subcellular localizations were also observed with green fluorescent protein fusion proteins in transfected fibroblasts (107). However, using the same antibody as that used for the previous study (which recognizes both UL35 and UL35a), a subsequent report observed only nuclear localization when an expression plasmid for full-length UL35 was transfected into fibroblasts (161). No Western blot analysis was provided to determine if this expression plasmid produced both UL35 and UL35a. Thus, the subcellular localization of these proteins remains an open question.

Deletion of the entire open reading frame from HCMV Towne identified UL35 as being a locus required for efficient replication at low MOIs (44). This phenotype was subsequently confirmed in another laboratory-adapted strain of the virus, HCMV AD169 (162). A transposon inserted into the amino-terminal end of the UL35 gene produced a virus without a growth defect (209), potentially indicating that UL35 and UL35a may have partially redundant functions or that UL35 is dispensable for viral replication. Mutants that express only UL35 or only UL35a will need to be created (perhaps by mutating the relevant start codons) to determine the functions of these individual proteins during HCMV infection.

Both UL35 and UL35a interact with pp71 (161); however, the functional significance of this interaction is unclear. Because pp71 facilitates viral IE gene expression, the UL35 proteins may also regulate this process. However, reporter assays with UL35 and the MIEP have so far given conflicting results (107, 161). Even consistent results would be hard to interpret, because it is well established that reporter assay results do not always indicate the way that the MIEP is regulated in the context of the viral genome in infected cells (119). Analysis of viral gene expression after infection with the UL35-null mutant led those authors to conclude that UL35 enhances IE gene expression (162). While this is certainly true, the data indicate that IE gene expression is only delayed in the mutant but eventually reaches levels that are comparable to those of the wild-type virus. However, accumulation of the early UL44 protein is dramatically reduced in the mutant (162), perhaps indicating that while UL35 has a modest effect on IE gene expression, it may have a much more significant effect on early gene expression.

Interestingly, an interaction between UL35 and pp71 may play a prominent role during viral egress. In cells infected with the UL35-null virus, pp71 (and pp65) remains in the nucleus at late times during infection and does not enter the cytoplasm with egressing capsids (162). Other assembly/egress defects were also noted. Thus, UL35 may control the incorporation of other viral proteins (such as pp71) into the tegument. Lower levels of pp71 in UL35-null virions could explain the delay in IE gene expression observed after infection with the mutant virus. A quantitative comparison of tegument proteins incorporated into wild-type and UL35-null virions is thus an essential experiment. Interestingly, UL35 appears to be only a minor component of the tegument. It was not identified in the original gel-based proteomics screen (9), and a later, more comprehensive screen estimated that an average of only about 80 molecules of UL35 are present in the virion (192). Thus, UL35 may have a catalytic (as opposed to a stoichiometric) role in tegument assembly, perhaps by influencing nucleocytoplasmic transport pathways, as was hypothesized previously (162).

ppUL69

The UL69 gene is expressed with early-late kinetics (201) and encodes a nuclear phosphoprotein that is incorporated into both virions and dense bodies (202). Only a single phophoisoform of UL69 is found in the tegument (202), but the role that phosphorylation plays in the activities of UL69 has not been explored. In reporter assays, UL69 increased luciferase expression from heterologous promoters (201) and, in cooperation with IRS1/TRS1, the HCMV MIEP (146). Subsequent work indicated that UL69 binds to SPT6, a cellular protein that modulates both chromatin structure and transcriptional elongation (203). A UL69 point mutant that is unable to bind SPT6 failed to activate expression from reporter constructs (203); however, that same mutant also failed to properly oligomerize (104), making the functional assay difficult to interpret.

UL69 also shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, and shuttling was found to be required for the transactivation of reporter constructs (102) and for the export of unspliced reporter RNAs from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (103). Thus, it was not surprising to find that UL69 binds to RNA nonspecifically, but what was surprising was that this ability to bind RNA was not required for UL69-mediated nuclear RNA export (187). However, the recent finding of UL69 localization to sites of viral gene expression (86) indicates that UL69 selects viral mRNAs for export because it accumulates at subnuclear sites where viral transcripts are synthesized. This mechanism may also explain why UL69 stimulates the expression of reporter constructs that contain an simian virus 40 intron (201). While in comparison to other herpesviral proteins, it seems likely that a role of UL69 is to help move the many unspliced HCMV messenger RNAs from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, it is now important to move away from reporter assays and to demonstrate that UL69 facilitates the nuclear export of true unspliced HCMV mRNAs within infected cells. Finally, because viral IE mRNAs are generally spliced, in contrast to early and late mRNAs, which are generally unspliced, it is unclear if viral mRNA export facilitated by tegument-delivered UL69 early during a lytic infection (as opposed to the export of early and late viral mRNAs by the newly synthesized protein) plays a significant role during HCMV infection. For an expanded discussion of the role of UL69 in mRNA export, readers are directed to a recent review by Toth and Stamminger (188).

Even if mRNA export mediated by UL69 is not important at the outset of HCMV infections, another function of this protein may be. The expression of UL69 arrests cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (80, 109) through an unknown mechanism. A virus lacking the UL69 gene fails to efficiently arrest cells in the G1 phase, indicating that UL69 contributes to, but is not solely responsible for, the G1 arrest observed in HCMV-infected cells (62). The UL69-null virus grows slowly but eventually produces a wild-type yield of virus (62). When total cellular RNA was analyzed, it was found that the mutant produces normal levels of IE and early messages (62). Because cells were not fractionated and protein levels were not analyzed, it is still unclear if the proposed ability of UL69 to export unspliced nuclear RNAs to the cytoplasm plays any role during HCMV infection. However, viral DNA replication was significantly delayed in cells infected with the UL69-null virus (62). Interestingly, positive effects of UL69 on viral DNA replication were observed in reporter assays (159), suggesting that the delay in virion production observed in the absence of UL69 may result from defects in viral DNA replication.

The current challenge is to identify UL69 mutations that fail to arrest the cell cycle and that fail to augment viral DNA replication (mutants that fail to export unspliced RNAs have already been characterized). Once created, all mutants must be examined for all of the activities of UL69 when expressed both alone and in the context of an HCMV infection. Only then will an accurate picture of the role or roles of UL69 during HCMV infection begin to emerge.

Summary

While tegument-delivered pp71 clearly controls IE gene expression and the course of HCMV infection (lytic replication versus latency), more work is needed to determine if other tegument proteins delivered to the cell upon HCMV infection also play key roles in viral gene expression. Pseudotyping of UL35- and UL69-null virions so that these proteins will be incorporated into the tegument layer of infectious virions and delivered to the cell, while not being expressed de novo from infecting viral genomes, should help in identifying and separating the roles that the tegument-delivered proteins play early during HCMV infection from the roles that the newly synthesized forms of the same proteins may play at later times.

IMMUNE EVASION

Viruses must inactivate cellular and organismal defenses for their successful replication and spread. HCMV tegument proteins target all types of antiviral immune measures including intrinsic, innate, and adaptive defenses. For example, the Daxx-mediated repression of IE gene expression is characterized as an intrinsic immune defense (152) and is neutralized by the pp71 protein, as described above. Additional tegument proteins such as pp65 and IRS1/TRS1 modulate innate and adaptive immune responses, as described below.

pp65 (ppUL83) (Lower Matrix Protein)

The pp65 phosphoprotein is the major constituent of HCMV particles (70, 145) and is delivered to the nucleus of permissive cells at the very start of a lytic infection (144). The protein is a target of both humoral and cellular immunity and is the dominant target antigen of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (15, 55, 76, 90, 118, 198). The persistence of this viral protein in the presence of strong immune surveillance implies that the protein serves a very important function during the viral life cycle. Numerous laboratories using various methods have mapped the gene encoding pp65 to the UL83 locus (33, 40, 130, 133, 149). Surprisingly, the UL83 gene is completely dispensable for replication in cultured fibroblasts but is essential for the formation of dense bodies (163).

Many HCMV genes not required for replication in vitro help the virus modulate or evade the immune system, and pp65 has been implicated in counteracting both innate and adaptive immune responses. pp65 was found to mediate the phosphorylation of viral IE proteins, which blocks their presentation by MHC class I molecules (52), and to cause the degradation of the HLA-DR alpha chain by mediating an accumulation of HLA class II molecules in the lysosome (131). In addition to these alterations of adaptive immunity, pp65 also protects infected cells from innate immunity by inhibiting natural killer cell cytotoxicity through an interaction with the NKp30 activating receptor (6).

Another branch of the innate immune system, the interferon response, was also found to be attenuated by pp65 (1, 25). The level of expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) was found to be elevated in cells infected with a pp65-null virus. This was a puzzling result for two reasons. First, the interferon response to HCMV infection is more robust in the absence of viral gene expression (e.g., infection with UV-inactivated virus), a condition where tegument-delivered pp65 presumably should attenuate ISG induction. This implies that a newly synthesized protein down-regulates this cellular antiviral response (24). Second, it is likely that a higher interferon response to infection with a pp65-null virus would cause a growth defect or delay in viral replication, where none is observed (163). An explanation for this paradox was proposed when it was determined that the pp65-null virus employed in the previous studies shows a delay in the expression of viral IE genes and that the viral IE2 protein is likely responsible for suppressing the expression of ISGs in HCMV-infected cells (184). Note that IE1 is also implicated in suppressing the interferon response (137). The delay in IE gene expression in the pp65-null virus is likely caused by a decrease in pp71 expression caused by the substitution of the UL83 gene with a selectable marker (184). pp65 and pp71 are neighboring genes expressed as a bicistronic mRNA (149), and previous studies described decreases in pp71 expression after targeting this message with an antisense RNA (38).

The most enigmatic characteristic assigned to pp65 is kinase activity. Early on, it was discovered that HCMV virions contained protein kinase activity (113) and that kinase activity was found to be associated with pp65 (22, 124, 173). Virion-associated kinase activity is diminished in the UL83-null virus (163), thus providing additional evidence for a pp65-associated kinase activity. Interestingly, this kinase activity appears to be important for preventing MHC presentation of IE proteins at the start of HCMV infections by phosphorylating the IE proteins on threonine residues (52). The unsettling aspect of this work is that the putative kinase domain of pp65 shows only modest similarity with other kinases (173), making it possible that the kinase activity observed in immunoprecipitates with pp65 antibodies resulted not from an intrinsic kinase activity of pp65 itself but from a copurifying, tightly associated cellular or viral kinase. An apparent resolution was the observation of an interaction of pp65 with polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1), and the localization of Plk1 kinase activity to wild-type, but not UL83-null, virions (47). However, that report did not test the ability of Plk1 to phosphorylate the IE proteins and detected Plk1-mediated phosphorylation of pp65 on serines only (47). Recently, pp65 has been found in association with the viral UL97 protein kinase (85), and cellular casein kinase II has also been found in virions (128).

The findings that HCMV virions contain multiple kinases and that pp65 associates with both a viral kinase and a cellular kinase do not necessarily mean that pp65 does not have kinase activity itself (despite the poor homology to known kinases). In fact, bacterially produced pp65 protein was reported to both autophosphorylate and phosphorylate casein in vitro on threonine residues only, and a mutation of the predicted catalytic lysine (K436N) abolished kinase activity (207). Thus, the mystery remains as to whether the kinase activity associated with pp65 is an activity of the protein itself, of the associated kinases to which it binds, or of both. Determination of whether or not the K436N protein associates with Plk1 (pp65 residues 398 to 456 are required for Plk1 binding) will be an informative experiment. More importantly, incorporating this mutation into the viral genome and testing this virus (along with wild-type virus produced from Plk1 knockdown cells) for virion kinase activity and the ability to prevent MHC presentation of IE peptides should help resolve this controversy. Finally, testing the sensitivity of pp65-associated kinase activity to the UL97-specific inhibitor maribavir (17) and assaying for pp65-associated kinase activity in cells infected with the UL97-null virus (139) will be telling experiments.

pIRS1/pTRS1

The IRS1 and TRS1 genes initiate in the “c” repeats that flank the US segment of the genome and extend into this region (197). They are members of the US22 family of genes (33). Their protein products are 100% identical over the amino-terminal 549 amino acids, and while their carboxy-terminal domains diverge, they still maintain 55% identity (33, 197). A promoter within the IRS gene leads to the production of a smaller in-frame version of pIRS1 termed pIRS1263 (146). pIRS1 and pTRS1 are detected in virions, NIEPS, and dense bodies, but IRS1263 is not (147). Approximately 220 molecules of pIRS1/pTRS1 are found per virion (192). The genes are expressed at IE times, and expression is maintained throughout the course of infection (177). The proteins accumulate to high levels only at later times and localize primarily to the cytoplasm in both infected and transfected cells (146), although nuclear localization of both proteins (as well as IRS1263) can be detected at early times after infection.

The IRS1 gene is nonessential (19, 54, 77), but a mutant in the TRS1 gene displays a 200-fold reduction in viral yields at a low MOI (19). No defects in viral mRNA accumulation were observed (3), perhaps because of the presence of the IRS1 gene in the TRS1 mutant. However, the absence of TRS1 resulted in an altered pattern of viral DNA accumulation in the nucleus and a defect in DNA packaging (3). As this is not observed in the absence of IRS1, this assembly function of TRS1 likely maps to the unique C terminus of the protein. It is unclear how a predominantly cytoplasmic protein could alter nuclear events such as viral DNA localization and packaging. An IRS1/TRS1 double knockout has yet to be generated.

The shutoff of protein synthesis upon viral infection is an antiviral response mediated by ISGs and double-stranded RNA, and many viruses have ways to counteract this innate immune defense (49). Both pIRS1 and pTRS1 can rescue the replication of mutant vaccinia virus (35) and HSV-1 (31) that are unable to counteract the shutoff of protein synthesis observed after infection because they lack their own proteins that counteract this cellular innate immune response. pIRS1/TRS1 prevent the phosphorylation of the α subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (31, 35) and the activation of RNase L (35), which help mediate protein synthesis shutoff. The identical amino-terminal portions of the proteins bind double-stranded RNA, and this binding is necessary but not sufficient to prevent protein synthesis shutoff (60). The similar but not identical carboxy-terminal portions of the proteins interact with protein kinase R (PKR). The full-length proteins prevent the activation (i.e., phosphorylation) of PKR and sequester it in the nucleus (61). Once again, it is not presently clear how proteins that localize to the cytoplasm, such as pIRS1/TRS1, can sequester PKR in the nucleus. Furthermore, this sequestration does not occur until 72 h postinfection, and presumably, efficient viral replication would require that the inhibition of the shutoff of protein synthesis occur much earlier. Because most of these experiments have been performed using nonpermissive cells (and ones that express other viral proteins, such as HeLa cells) and not in the context of an HCMV infection, it is unclear what role that the ability of pIRS1/TRS1 to inhibit the shutoff of protein synthesis plays during HCMV infection.

In reporter assays, the IRS1 and TRS1 proteins activate transcription from various viral early and late promoters (and the promoter that drives the expression of pIRS1263) but only in cooperation with the viral UL69, IE1, and IE2 proteins (73, 91, 146, 177). The IRS1263 protein was found to antagonize transcription stimulated by the IE proteins in similar assays (146). It is presently unclear whether the effects observed in reporter assays actually represent a modulation of transcription or (more likely) result from the effects of these cytoplasmic proteins on translation described above.

Summary

IRS1/TRS1 and pp65 inactivate cellular defenses against HCMV infection; however, detailed mechanisms for how they accomplish this important task remain to be elucidated. Importantly, it is presently unclear if tegument-delivered proteins or newly synthesized proteins are the major immune regulators.

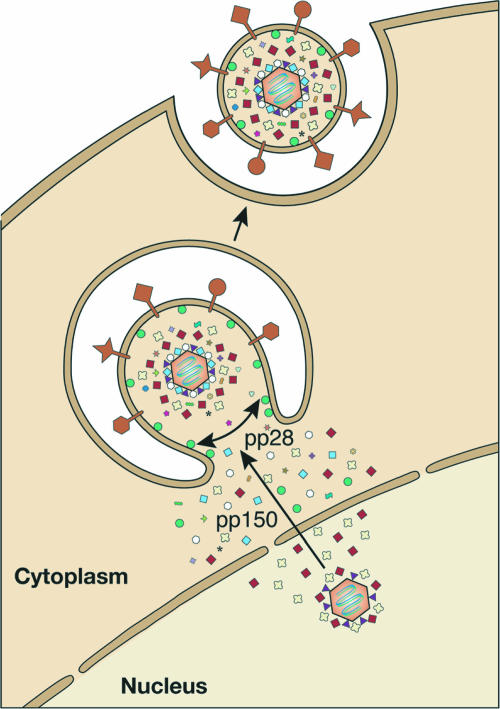

ASSEMBLY AND EGRESS

After viral DNA is replicated and viral late genes are expressed, capsid formation and genomic DNA packaging into the preformed capsids occur in the nucleus. These DNA-containing capsids then leave the cell through an envelopment-deenvelopment-reenvelopment process (120). Capsids acquire a primary envelope when they bud through the inner nuclear membrane into the perinuclear space, lose that envelope when they bud through the outer nuclear membrane into the cytoplasm, and acquire their final envelope when they bud into Golgi apparatus-derived vesicles. The fusion of these vesicles with the cell membrane results in the release of the enveloped virion. As described in the introduction, other types of tegument-containing particles, NIEPS and dense bodies, are also produced in vitro from HCMV-infected cells. Most of the tegument proteins are thought to be acquired in the cytoplasm, although it is likely that some associate with the capsid in the nucleus. How tegument proteins control viral assembly and egress and how they are incorporated into virions are poorly understood processes but are topics currently under intense study.

ppUL97

The UL97 gene is expressed with early-late kinetics (199), and the protein, which localizes to the nucleus (123), is a minor component of NIEPS and virions (191, 192). UL97 is a protein kinase that phosphorylates (and thus activates) the antiviral drug ganciclovir (105, 181) as well as the viral UL44 protein (97, 114) and the cellular EF-1δ (88), p32, and lamin (115) proteins. Although not absolutely required for viral replication, null mutants of UL97 show a 100- to 1,000-fold growth defect (139). A minor defect in the absence of UL97 activity, by either genetic mutation or pharmacological inhibition, is a decrease in viral DNA replication by between 5- and 20-fold (17, 96, 204).

A more significant defect in assembly and egress is also observed, although the exact step that is impaired is controversial. Reports described defects in DNA packaging (204), the exit of DNA-containing capsids from the nucleus (96), the mislocalization of yet-to-be-packaged tegument proteins in either the nucleus (140) or the cytoplasm (8), and the disruption of nuclear aggresomes containing viral tegument proteins (141). Effects of UL97 deletion or inhibition on any or all of these processes could explain the growth defect observed in the absence of UL97 kinase activity. The incorporation and phosphorylation statuses of tegument proteins in UL97-null virions have yet to be examined, and such an experiment may help elucidate the mechanism through which UL97 modulates assembly and egress. Recently, UL97 was shown to possess cyclin-dependent kinase-like activity and to stimulate cell cycle progression by directly phosphorylating the Rb protein (67). Rb phosphorylation by UL97 could enhance viral DNA replication by stimulating the expression of the E2F-responsive genes required for DNA replication and entry into the S phase of the cell cycle (41). UL97 contains three putative Rb-binding motifs (67, 141) that appear to contribute to, but are not absolutely required for, UL97-mediated Rb phosphorylation (141). As mentioned above, UL97 disrupts aggregated tegument proteins, and the ability of UL97 to phosphorylate Rb may play a role in aggresome disruption and, thus, in virion assembly and egress (141). The kinase activity of UL97 is clearly important at many different steps during HCMV infection. The current challenge is to elucidate how UL97-mediated phosphorylation of individual viral and cellular proteins impacts HCMV infection.

pp150 (UL32)

Originally termed BPP for basic phosphoprotein (50), pp150 is the highly immunogenic (76, 99) protein product of the UL32 gene (75). pp150 is phosphorylated (50), but the modification sites have not been mapped, nor have the functional consequences of pp150 phosphorylation been examined. pp150 is also modified by O-linked N-acetylglucosamine on serine residues located at amino acids 921 and 952 (16, 56). The substitution of alanine for either of these serines individually does not inhibit pp150 function (7). The phenotype of a double O-linked N-acetylglucosamine site mutant has not been reported.

pp150 is the second most abundant tegument protein (behind only pp65), with approximately 1,500 copies per virion (192). Similar levels were found in NIEPS, but very little pp150 was observed in dense bodies (70, 145). Virions and NIEPS contain viral capsids, but dense bodies do not. pp150 interacts with preformed capsids (but apparently not with any capsid protein when they are expressed individually) via its amino-terminal 275 amino acids (13), and the amino terminus of pp150 is required for HCMV infection (7), as determined with the UL32-null virus secondary spread assay described below. One testable hypothesis generated by these studies that should be explored is that the amino terminus of pp150 is required for the incorporation of pp150 into virions. A controversial point is in which compartment of the cell pp150 initially associates with capsids. Some studies detected nuclear localization of pp150 (64, 156), while others detected only cytoplasmic localization (7, 157, 190). No matter where this interaction takes place, it is likely that the pp150 association with the capsid is one of the steps, if not the earliest step, in tegument assembly.

Global analyses of viral mutants showed that pp150 is absolutely essential for productive HCMV replication (44, 209), a result predicted by two earlier studies (122, 210). A naturally occurring pp150 mutant detected along with wild-type virus in a viral isolate from a heart transplant patient could not be purified to homogeneity (210), indicating that pp150 may be required for HCMV replication. Because it is unknown whether this mutant had additional mutations, a firm conclusion as to the necessity of pp150 could not be drawn. Similarly, stably expressed antisense mRNA to pp150 inhibited HCMV replication in astrocytoma cells (122). However, because these cells also showed decreased levels of expression of gB upon HCMV infection, the growth phenotype could not be prescribed only to the loss of pp150.

The partial complementation of a UL32-null, green fluorescent protein-expressing BAC clone (44) was achieved by cotransfecting the BAC with an expression plasmid for pp150 or by transfecting cells that constitutively express low levels of pp150 (7). Monitoring the secondary spread of the viral infection from the initially transfected cells by fluorescence microscopy allowed a more thorough characterization of the null virus phenotype than was previously possible. No defects were observed in viral gene expression or DNA replication, but infectious particles were rarely produced, even in the complementing cells. After observing bromodeoxyuridine-labeled DNA and the major capsid protein in the cytoplasm, those authors concluded that the lack of pp150 does not prevent nuclear egress but blocks virion maturation somewhere in the cytoplasm (7). However, the labeled DNA observed in the cytoplasm was synthesized 48 h earlier in cells that express pp150. Thus, while those authors implied that this DNA represents virions that have left the nucleus and are trapped in the cytoplasm (and this is likely the case), it could represent virus that has completed egress, entered a different cell, and is trapped during the process of entry and uncoating. Likewise, the major capsid protein localized in the cytoplasm is assumed to be fully formed capsids that have left the nucleus and are trapped in the cytoplasm in the absence of pp150 (and it likely is), but it could represent the accumulation of the monomeric protein due to a pp150-related defect in nuclear capsid assembly. Finally, dense bodies may still form in the absence of pp150 because pp65 (but not the IE proteins) was detected in the nuclei of cells surrounding those that were transfected with the UL32-null BAC DNA (7). Together, all of the data point to an essential role for pp150 in directing capsids to the site of final envelopment; however, whether this role is confined to the cytoplasm or has a nuclear component is still unclear. In addition, any possible role of pp150 during entry has yet to be explored.

pp28 (UL99)

pp28 is a highly immunogenic phosphoprotein found in virions, NIEPS, and dense bodies that is expressed with late kinetics (70, 121, 129, 142). It is 190 amino acids long and is encoded by the UL99 gene, whose expression pattern and promoter have been extensively studied (33, 42, 92, 98, 117, 199). Through the myristoylation of a glycine residue at the second amino acid position, pp28 associates with cellular and viral membranes (158). In HCMV-infected cells, pp28 colocalizes with other tegument and viral glycoproteins at juxtanuclear structures likely derived from the Golgi apparatus that presumably represent the site of viral assembly and final envelopment (100, 157). Both myristoylation and a cluster of acidic residues (amino acids 44 to 59) are required for this localization and for incorporation into virions (79, 158, 164).

A pp28-null mutant fails to make infectious virus, although there are no defects in viral DNA replication or gene expression (166). In cells infected with this mutant, other viral tegument and glycoproteins accumulate at the cytoplasmic assembly sites, and DNA-filled, tegument protein-associated capsids accumulate in the cytoplasm but fail to associate with the preformed assembly sites (166). Thus, it appears that pp28 is required for the final envelopment of infectious virions. A recombinant HCMV encoding only a mutated pp28 lacking the myristoylation site also failed to produce infectious particles (23). However, viruses that express only the amino-terminal 61 (164) or 57 (79) amino acids replicate almost as well as wild-type virus, indicating that a significant region (∼75%) of the carboxy terminus of the protein is dispensable. Deletion from the C terminus to amino acid 50 produces viable viruses with significant growth defects (164, 165), and deletions to amino acid 43 are not viable (79). Deletion of the stretch of acidic residues between amino acids 44 and 59 also leads to the inability to recover infectious virus. Thus, studies so far indicate that that localization of pp28 to the site of final envelopment is necessary for the production of infectious viral progeny. Finally, a careful examination of the pp28-null mutant revealed that in the absence of infectious particle production, this virus (as well as the wild type) can spread directly from one cell to other adjacent cells (167). Further work is required to confirm and characterize this alternative method of viral spread and to determine if it represents, as those authors speculated, a means by which the virus might avoid a neutralizing antibody response.

Summary

The roles that pp150 and pp28 play in viral egress are similar yet have some important distinctions. It appears that pp150 is required to incorporate capsids into particles but not to make particles themselves. Even in the absence of pp150, the spread of pp65 likely signifies that dense bodies are formed (7). The formation of dense bodies by pp28-null viruses has not been examined. However, DNA-containing capsids appear to be able to spread from cell to cell in the absence of pp28 (167) but not in the absence of pp150 (7). Thus, pp150 may affect the stability of cytoplasmic capsids or direct their movement within the cytoplasm (e.g., to the assembly site for particle formation or the plasma membrane for cell-to-cell spread), while pp28 controls the enclosure of tegument proteins and capsids within an enveloped particle (Fig. 4). Finally, the phosphorylation of tegument proteins by UL97 may facilitate their incorporation into virions, although evidence for this hypothesis is lacking.

FIG. 4.

HCMV egress. DNA-containing capsids may associate with some tegument proteins while still in the nucleus. After exiting the nucleus by an envelopment-deenvelopment pathway (not shown), they acquire more tegument proteins in the cytoplasm. Tegumented capsids migrate to assembly sites located on Golgi apparatus-derived vesicles, where they obtain their final envelope that contains viral glycoproteins. The eventual fusion of these vesicles with the cell membrane results in the release of fully formed virions. The pp150 protein likely plays a role in directing capsids to assembly sites, and the pp28 protein likely plays a role in the formation of viral particles. Symbols are as shown in Fig. 1.

OTHER TEGUMENT PROTEINS

The UL25 protein is present in about 350 copies per virion (192) and appears to be more abundant in dense bodies (9). It is detected in Western blots as a doublet around 85 kDa (12). The protein is highly immunogenic (101), is likely phosphorylated (12), and colocalizes with pp28 in cytoplasmic structures (12) that are thought to represent the site of final envelopment. A function for UL25 has not been proposed. The gene is nonessential (44, 209) and has limited homology to UL35.

UL26 is found in virions and perhaps at higher levels in dense bodies (9, 192). Two isoforms of UL26 do not appear to be phosphorylated, accumulate in the nucleus of HCMV-infected cells, and activate expression from the MIEP in reporter assays (176). The UL26 gene is a member of the US22 family that is expressed with early-late kinetics (176) and is required for efficient viral replication (44, 108, 127, 209). The growth defect of a UL26-null virus can be complemented in large part by ectopically expressed UL26 (127) and partially by IE1 (108). A decreased stability of proteins or particles may account for the growth defect of UL26 mutant viruses, but there is disagreement as to whether this is manifested shortly after infection or at very late times. One report defined specific defects very early during the replication cycle, such as decreased viral IE gene syntheses and a decreased stability of the pp28 tegument protein after viral entry (127). Because only hypophosphorylated pp28 was found in UL26-null virions, those authors concluded that alterations in the phosphorylation state of one or more tegument proteins affect their stability after viral entry into newly infected cells (127). Interestingly, the particle/PFU ratio was not altered (127), so while the defect appears to be established at late times, it does not manifest itself until the IE phase in a newly infected cell. Another report detected no defects at IE times and increased tegument incorporation of pp71 but found a larger number of noninfectious particles and a decrease in the stability of UL26-null virions (108). In that report, the defect is both established and manifested at late times. Thus, while UL26 appears to play a role in tegument assembly/disassembly and tegument protein/virion stability, it is unclear if this defect is displayed at IE times only, late times only, or both. Finally, it is uncertain how the observation that UL26 is likely to be a minor constituent of the tegument (9), perhaps present at as low as 15 copies per virion (192), relates to the function of this protein.

UL36 (136) and UL38 (192) are found in the tegument and inhibit apoptosis (171, 186). UL36 inhibits the extrinsic apoptosis pathway (171), while UL38 inhibits intrinsic and endoplasmic reticulum-mediated apoptotic pathways (186). In addition to these two tegument proteins, HCMV also encodes a nontegument protein (UL37x1) and a noncoding RNA (β2.7) that also inhibit apoptosis (53, 143). For a more detailed discussion of HCMV interference with apoptotic pathways, readers are directed to a recent review by Andoniou and Degli-Esposti (5).

The UL45 gene is expressed with early-late kinetics, and its protein product accumulates only after viral DNA replication (135). The protein is incorporated into virions independent of the pp65 protein (135) at a level of about 750 copies per virion (192). UL45 has significant homology to the large (R1) subunit of ribonucleotide reductase (33), although it lacks many catalytic residues and does not appear to functionally contribute to ribonucleotide reductase activity (135). Mutant viruses have been constructed in both clinical (59) and laboratory (135) strains of the virus, and they show no growth defect at high MOIs and a moderate (50-fold) growth defect at a low MOI (0.1). A function for HCMV UL45 has not been proposed, and experimental evidence does not support a role for UL45 in regulating nucleotide pools during HCMV infection (135). Perhaps this is not surprising, as HCMV infection has been shown to increase the expression of cellular ribonucleotide reductase subunits (174). While the murine cytomegalovirus homolog (M45) has been reported to have an antiapoptotic function and to be required for endothelial cell tropism (26), neither of these activities is conserved in HCMV UL45. Thus, the function of this protein remains to be discovered.

The UL76 gene is expressed with true late kinetics (196) and is classified as being either augmenting (209) or essential (44). The monomeric protein is incorporated into virions, NIEPS, and dense bodies, and a higher-molecular-weight form is found specifically in virions (196). UL76 localizes to the nucleus (195, 196), modestly regulates expression from viral promoters in reporter assays (195), and appears to inhibit HCMV replication when preexpressed in semipermissive U373 MG cells (196). It is presently unclear how to reconcile the negative effects of preexpressing the protein with the negative effects of deleting the gene.

UL77 is incorporated at about 100 molecules per virion (192) and contains a putative pyruvoyl decarboxylase domain (208). Thus, it may be involved in polyamine synthesis, a process critical to HCMV replication (51). The UL77 gene is essential (44, 209).

Viruses lacking the UL88 gene show either no (209) or very modest (44) growth defects. UL88 is found in virions, NIEPs, and dense bodies (9), and about 100 molecules are incorporated into the average virion (192). No reports of a function of UL88 have been presented.

The 36-kDa UL94 protein (200) is present at about 200 molecules per virion (192), and its localization within virions has been confirmed with a monoclonal antibody (200). It has been classified as being either an essential (44) or an augmenting (209) protein. UL94 is expressed only at late times of infection, localizes to the nucleus in both transfected and infected cells, and may exist as a disulfide-linked dimer (200). The amino acid sequence of UL94 reveals a possible zinc and/or nucleic acid binding domain (200), but the function of this protein has not been determined. However, UL94 is medically relevant in systemic sclerosis, an autoimmune disease characterized by vascular damage and excessive extracellular matrix deposition. Most systemic sclerosis patients have antibodies that recognize a specific epitope of UL94 (GGAGIWL) that shares homology to both intracellular and cell surface autoantigens (110) such as the NAG-2 protein. NAG-2 is a cell surface receptor that associates with integrins (182). Antibodies to the UL94 peptide recognize and bind to NAG-2 on endothelial and fibroblasts cells (110, 111). This leads to the activation of signal transduction pathways that result in endothelial cell apoptosis and the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines and extracellular matrix molecules by fibroblasts. Thus, anti-UL94 antibodies induce changes in cells that are consistent with those seen in systemic sclerosis and may be linked to the pathogenesis of this autoimmune disease (110, 111).

The US24 gene is expressed with early kinetics (32), has been classified as being dispensable in the Towne viral strain (44) but augmenting in AD169 (209), and encodes a tegument protein (192) found in virions, NIEPS, and dense bodies (46). AD169 mutants lacking US24 show a 20- to 30-fold growth defect and a 10-fold-higher particle/PFU ratio (46). Cells infected with the mutant show a minor delay in the expression of IE1, a moderate reduction in the levels of the early protein UL44, and significantly less pp28 protein (46). The mechanism behind these deficiencies, and, thus, the role of US24, is not known.

Minor tegument components identified by mass spectrometry include US23, UL44 (DNA polymerase processivity factor), UL51 (terminase component), UL54 (DNA polymerase), UL57 (single-stranded DNA-binding protein), UL71, UL72 (dUTPase homolog), UL79, UL84 (viral DNA replication factor), UL89 (terminase component), UL96, UL103, UL104 (portal protein), and UL112 (126, 192). In addition to those described above (UL36, IRS1 [TRS1], and US24), other members of the US22 family, namely, UL23, UL24, UL43, US22, and US23, are also incorporated into virions (2, 192). It is not known if additional members of the family (UL28, UL29, and US26) are virion proteins, but they are required for efficient viral replication (44, 209).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Viral proteins that localize to the HCMV tegument play important roles in viral entry, gene expression, immune evasion, assembly, and egress. The mechanisms through which tegument proteins mediate these functions are beginning to emerge. More emphasis should be directed at determining the role of tegument protein phosphorylation and what roles (if any) tegument proteins play when latent infections are established or reactivated. However, the largest gap in our knowledge is an understanding of how specific viral proteins are selected for incorporation into the tegument layer of virions. The mechanism through which tegument proteins are incorporated into virions is poorly understood. While association with the capsid or with the cytoplasmic tails of envelope glycoproteins is a likely mechanism, few, if any, studies have addressed this possibility. Knowing how tegument proteins are incorporated into virions is important for many reasons. First, because many tegument proteins are either essential for or augmenting to viral replication (Table 1), therapeutic inhibition of their incorporation into virions could be a means of antiviral intervention. Second, an understanding of tegumentation will increase our knowledge of viral assembly and egress and, possibly, how the virus disassembles during entry. Third, preventing the incorporation of tegument proteins into infectious virions will aid in defining the roles of tegument-delivered versus newly synthesized viral proteins. Last, as herpesvirus vectors are being explored as delivery vehicles for gene therapy (45), learning how to specifically incorporate desired proteins (or other macromolecules) into these virions may open additional avenues for therapies.

Acknowledgments

I thank Leanne Olds for the figure illustrations and Ryan Saffert, Adam Hume, and Jiwon Hwang for stimulating discussions and comments on the manuscript.

Work in my laboratory is supported by grants from the American Heart Association, the Wisconsin Partnership Fund for a Healthy Future, the NIH (1R56-AI64703-01A2 bridge award), and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (Investigator in Pathogenesis award).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abate, D. A., S. Watanabe, and E. Mocarski. 2004. Major human cytomegalovirus structural protein pp65 (ppUL83) prevents interferon response factor 3 activation in the interferon response. J. Virol. 7810995-11006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adair, R., E. R. Douglas, J. B. Maclean, S. Y. Graham, J. D. Aitken, F. E. Jamieson, and D. J. Dargan. 2002. The products of human cytomegalovirus genes UL23, UL24, UL43 and US22 are tegument components. J. Gen. Virol. 831315-1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adamo, J. E., J. Schroer, and T. Shenk. 2004. Human cytomegalovirus TRS1 protein is required for efficient assembly of DNA-containing capsids. J. Virol. 7810221-10229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agromayor, M., and J. Martin-Serrano. 2006. Interaction of AMSH with ESCRT-III and deubiquitination of endosomal cargo. J. Biol. Chem. 28123083-23091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andoniou, C. E., and M. A. Degli-Esposti. 2006. Insights into the mechanisms of CMV-mediated interference with cellular apoptosis. Immunol. Cell Biol. 8499-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnon, T. I., H. Achdout, O. Levi, G. Markel, N. Saleh, G. Katz, R. Gazit, T. Gonen-Gross, J. Hanna, E. Nahari, A. Porgador, A. Honigman, B. Plachter, D. Mevorach, D. G. Wolf, and O. Mandelboim. 2005. Inhibition of the NKp30 activating receptor by pp65 of human cytomegalovirus. Nat. Immunol. 6515-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AuCoin, D. P., G. B. Smith, C. D. Meiering, and E. S. Mocarski. 2006. Betaherpesvirus-conserved cytomegalovirus tegument protein ppUL32 (pp150) controls cytoplasmic events during virion maturation. J. Virol. 808199-8210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azzeh, M., A. Honigman, A. Taraboulos, A. Rouvinski, and D. G. Wolf. 2006. Structural changes in human cytomegalovirus cytoplasmic assembly sites in the absence of UL97 kinase activity. Virology 35469-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldick, C. J., and T. Shenk. 1996. Proteins associated with purified human cytomegalovirus particles. J. Virol. 706097-6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldick, C. J., A. Marchini, C. E. Patterson, and T. Shenk. 1997. Human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 (ppUL82) enhances the infectivity of viral DNA and accelerates the infectious cycle. J. Virol. 714400-4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batterson, W., D. Furlong, and B. Roizman. 1983. Molecular genetics of herpes simplex virus. VIII. Further characterization of a temperature-sensitive mutant defective in the release of viral DNA and in other stages of the viral reproductive cycle. J. Virol. 45397-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Battista, M. C., G. Bergamini, M. C. Boccuni, F. Campanini, A. Ripalti, and M. P. Landini. 1999. Expression and characterization of a novel structural protein of human cytomegalovirus, pUL25. J. Virol. 733800-3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baxter, M. K., and W. Gibson. 2001. Cytomegalovirus basic phosphoprotein (pUL32) binds to capsids in vitro through its amino one-third. J. Virol. 756865-6873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bechtel, J. T., and T. Shenk. 2002. Human cytomegalovirus UL47 tegument protein functions after entry and before immediate-early gene expression. J. Virol. 761043-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beninga, J., B. Kropff, and M. Mach. 1995. Comparative analysis of fourteen individual human cytomegalovirus proteins for helper T cell response. J. Gen. Virol. 76153-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benko, D. M., R. S. Haltiwanger, G. W. Hart, and W. Gibson. 1988. Virion basic phosphoprotein from human cytomegalovirus contains O-linked N-acetylglucosamine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 852573-2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biron, K. K., R. J. Harvey, S. C. Chamberlain, S. S. Good, A. A. Smith, M. G. Davis, C. L. Talarico, W. H. Miller, R. Ferris, R. E. Dornsife, S. C. Stanat, J. C. Drach, L. B. Townsend, and G. W. Koszalka. 2002. Potent and selective inhibition of human cytomegalovirus replication by 1263W94, a benzimidazole l-riboside with a unique mode of action. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 462365-2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biron, K. K. 2006. Antiviral drugs for cytomegalovirus disease. Antivir. Res. 71154-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blankenship, C. A., and T. Shenk. 2002. Mutant human cytomegalovirus lacking the immediate-early TRS1 coding region exhibits a late defect. J. Virol. 7612290-12299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradshaw, P. A., R. Duran-Guarino, S. Perkins, J. I. Rowe, J. Fernandez, K. E. Fry, G. R. Reyes, L. Young, and S. K. H. Foung. 1994. Localization of antigenic sites on human cytomegalovirus virion structural proteins encoded by UL48 and UL56. Virology 205321-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bresnahan, W. A., and T. Shenk. 2000. UL82 virion protein activates expression of immediate early viral genes in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9714506-14511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Britt, W. J., and D. Auger. 1986. Human cytomegalovirus virion-associated protein with kinase activity. J. Virol. 59185-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Britt, W. J., M. Jarvis, J.-Y. Seo, D. Drummond, and J. Nelson. 2004. Rapid genetic engineering of human cytomegalovirus by using a lambda phage linear recombination system: demonstration that pp28 (UL99) is essential for production of infectious virus. J. Virol. 78539-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Browne, E. P., B. Wing, D. Coleman, and T. Shenk. 2001. Altered cellular mRNA levels in human cytomegalovirus-infected fibroblasts: viral block to the accumulation of antiviral mRNAs. J. Virol. 7512319-12330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]