Abstract

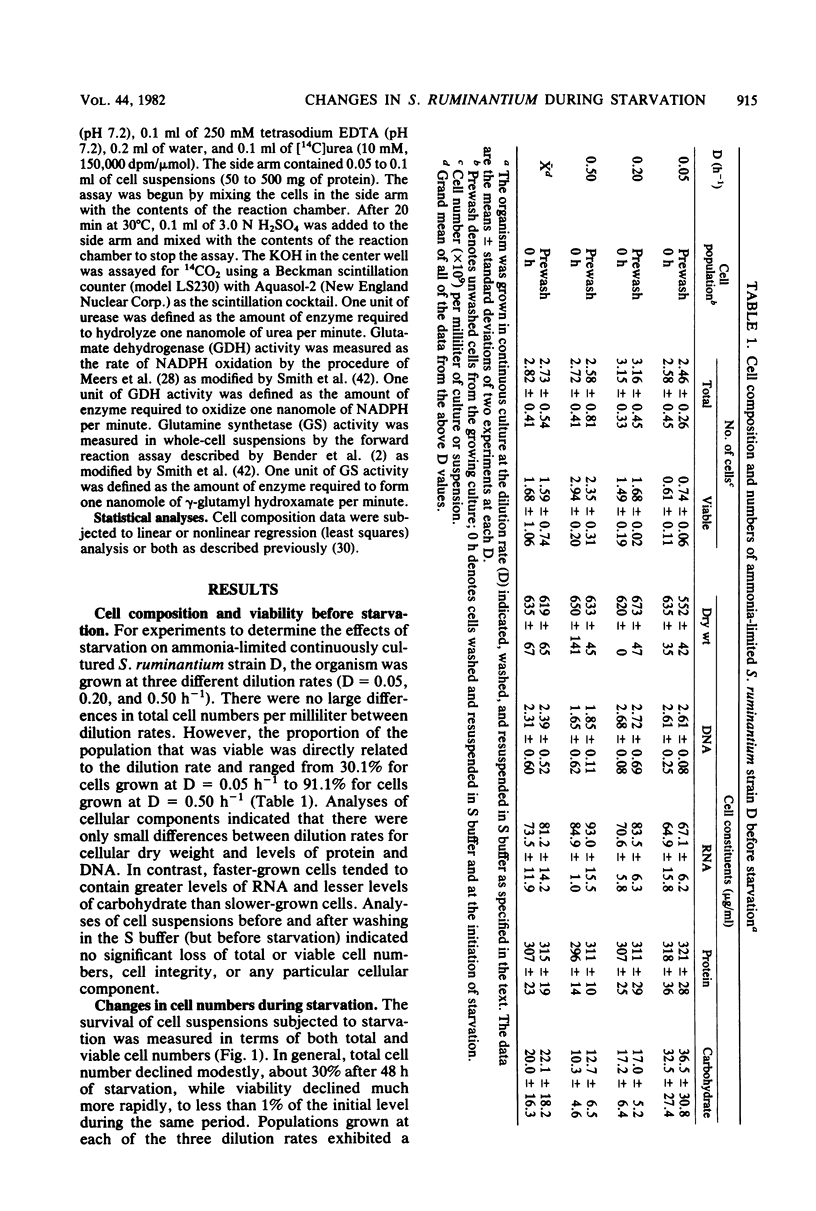

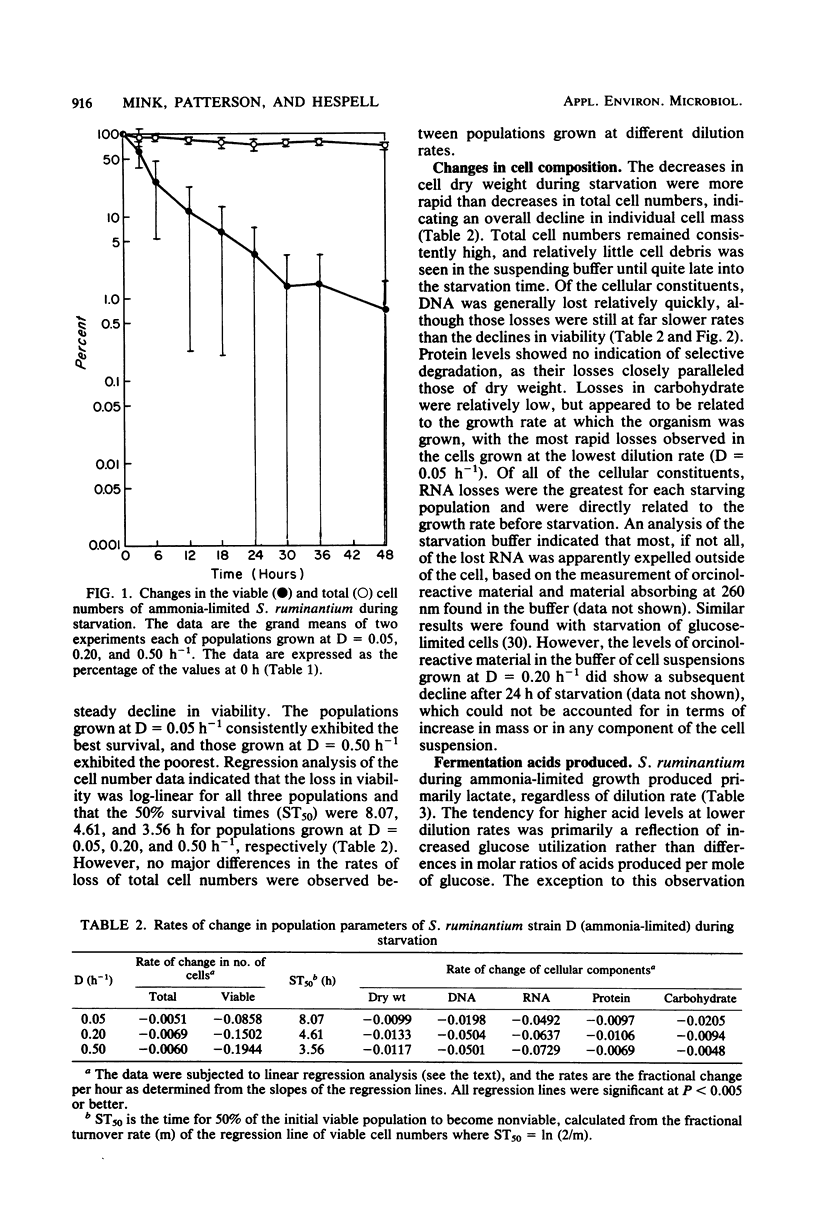

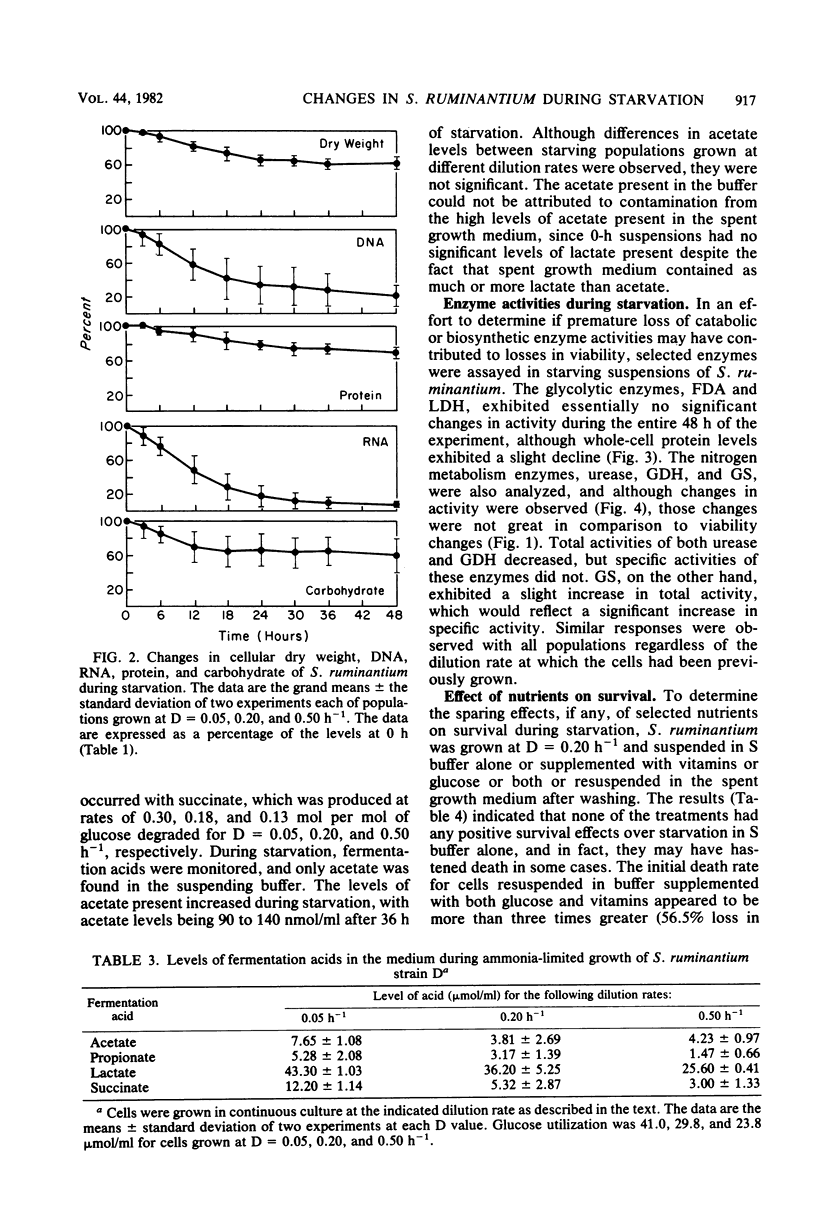

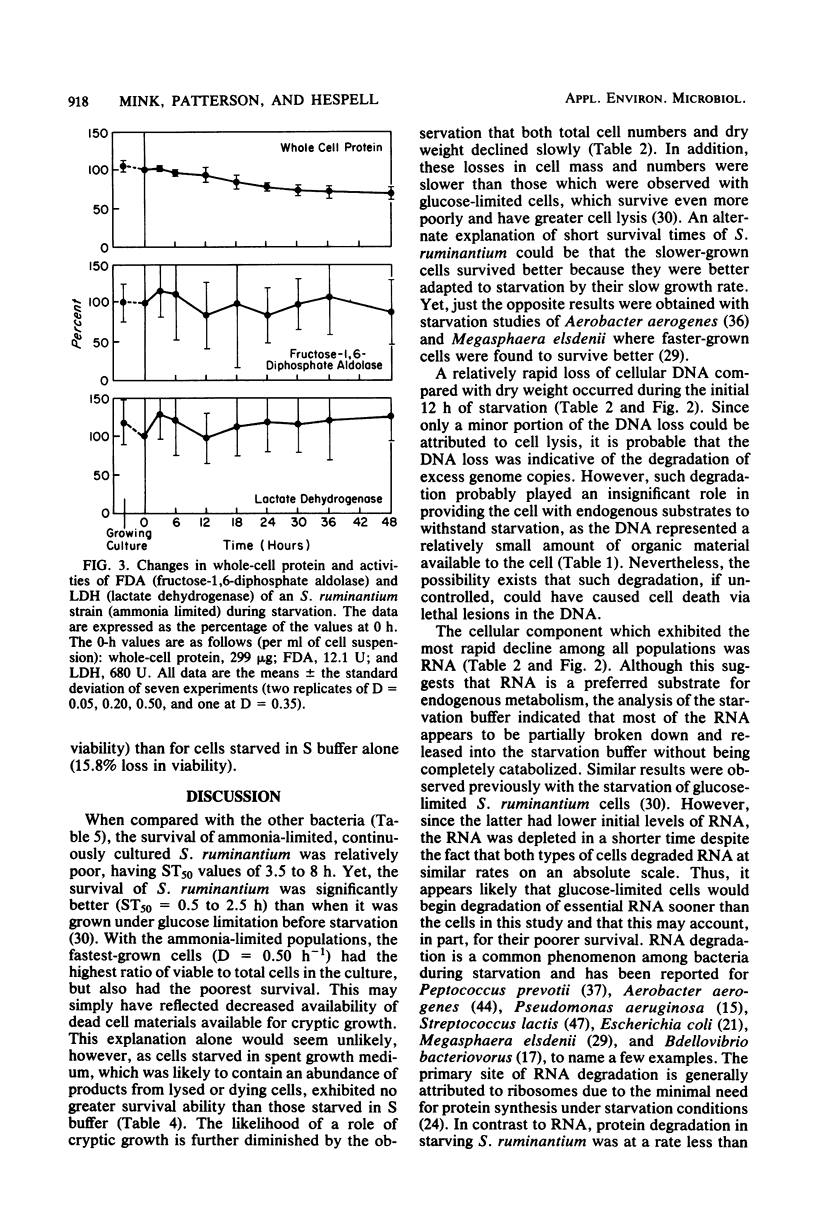

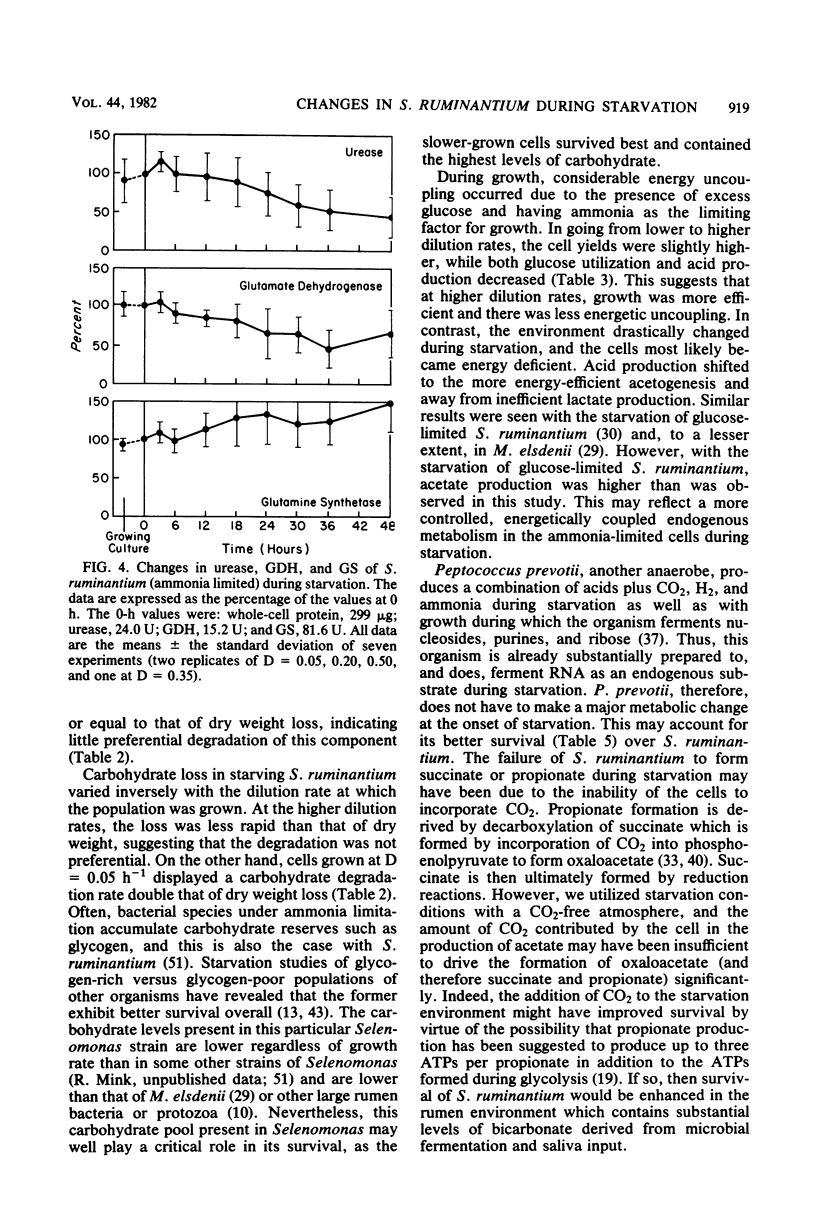

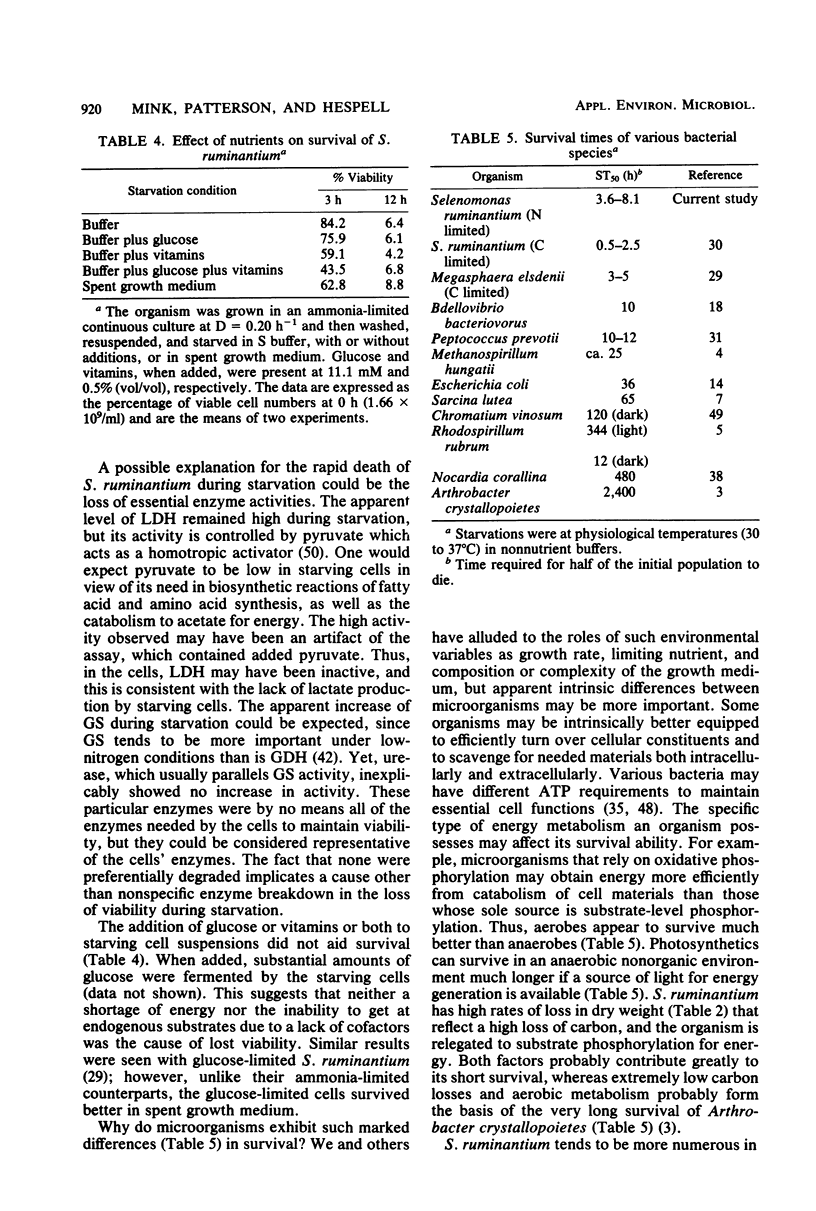

Under nitrogen (ammonia)-limited continuous culture conditions, the ruminal anaerobe Selenomonas ruminantium was grown at various dilution rates (D). The proportion of the population that was viable increased with D, being 91% at D = 0.5 h−1. Washed cell suspensions were subjected to long-term nutrient starvation at 39°C. All populations exhibited logarithmic linear declines in viability that were related to the growth rate. Cells grown at D = 0.05, 0.20, and 0.50 lost about 50% viability after 8.1, 4.6, and 3.6 h, respectively. The linear rates of decline in total cell numbers were dramatically less and constant regardless of dilution rate. All major cell constituents declined during starvation, with the rates of decline being greatest with RNA, followed by DNA, carbohydrate, cell dry weight, and protein. The rates of RNA loss increased with cells grown at higher D values, whereas the opposite was observed for rates of carbohydrate losses. The majority of the degraded RNA was not catabolized but was excreted into the suspending buffer. At all D values, S. ruminantium produced mainly lactate and lesser amounts of acetate, propionate, and succinate during growth. With starvation, only small amounts of acetate were produced. Addition of glucose, vitamins, or both to the suspending buffer or starvation in the spent culture medium resulted in greater losses of viability than in buffer alone. Examination of extracts made from starving cells indicated that fructose diphosphate aldolase and lactate dehydrogenase activities remained relatively constant. Both urease and glutamate dehydrogenase activities declined gradually during starvation, whereas glutamine synthetase activity increased slightly. The data indicate that nitrogen (ammonia)-limited S. ruminantium cells have limited survival capacity, but this capacity is greater than that found previously with energy (glucose)-limited cells. Apparently no one cellular constituent serves as a catabolic substrate for endogenous metabolism. Relative to losses in viability, cellular enzymes are stable, indicating that nonviable cells maintain potential metabolic activity and that generalized, nonspecific enzyme degradation is not a major factor contributing to viability loss.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BURTON K. A study of the conditions and mechanism of the diphenylamine reaction for the colorimetric estimation of deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochem J. 1956 Feb;62(2):315–323. doi: 10.1042/bj0620315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender R. A., Janssen K. A., Resnick A. D., Blumenberg M., Foor F., Magasanik B. Biochemical parameters of glutamine synthetase from Klebsiella aerogenes. J Bacteriol. 1977 Feb;129(2):1001–1009. doi: 10.1128/jb.129.2.1001-1009.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuil C., Patel G. B. Viability and depletion of cell constituents of Methanospirillum hungatii GP1 during starvation. Can J Microbiol. 1980 Aug;26(8):887–892. doi: 10.1139/m80-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breznak J. A., Potrikus C. J., Pfennig N., Ensign J. C. Viability and endogenous substrates used during starvation survival of Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol. 1978 May;134(2):381–388. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.2.381-388.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleigh I. G., Dawes E. A. Studies on the endogenous metabolism and senescence of starved Sarcina lutea. Biochem J. 1967 Jan;102(1):236–250. doi: 10.1042/bj1020236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANEY A. L., MARBACH E. P. Modified reagents for determination of urea and ammonia. Clin Chem. 1962 Apr;8:130–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czerkawski J. W. Chemical composition of microbial matter in the rumen. J Sci Food Agric. 1976 Jul;27(7):621–632. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740270707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWES E. A., RIBBONS D. W. STUDIES ON THE ENDOGENOUS METABOLISM OF ESCHERICHIA COLI. Biochem J. 1965 May;95:332–343. doi: 10.1042/bj0950332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWES E. A., RIBBONS D. W. The endogenous metabolism of microorganisms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1962;16:241–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.16.100162.001325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensign J. C. Long-term starvation survival of rod and spherical cells of Arthrobacter crystallopoietes. J Bacteriol. 1970 Sep;103(3):569–577. doi: 10.1128/jb.103.3.569-577.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronlund A. F., Campbell J. J. Enzymatic Degradation of Ribosomes During Endogenous Respiration of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1965 Jul;90(1):1–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.90.1.1-7.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hespell R. B., Canale-Parola E. Carbohydrate metabolism in Spirochaeta stenostrepta. J Bacteriol. 1970 Jul;103(1):216–226. doi: 10.1128/jb.103.1.216-226.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hespell R. B., Mertens M. Effects of nuclei acid compounds on viability and cell composition of Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus during starvation. Arch Microbiol. 1978 Feb;116(2):151–159. doi: 10.1007/BF00406030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hespell R. B., Miozzari G. F., Rittenberg S. C. Ribonucleic acid destruction and synthesis during intraperiplasmic growth of Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. J Bacteriol. 1975 Aug;123(2):481–491. doi: 10.1128/jb.123.2.481-491.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannotti E. L., Kafkewitz D., Wolin M. J., Bryant M. P. Glucose fermentation products in Ruminococcus albus grown in continuous culture with Vibrio succinogenes: changes caused by interspecies transfer of H 2 . J Bacteriol. 1973 Jun;114(3):1231–1240. doi: 10.1128/jb.114.3.1231-1240.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson A., Gillespie D. Metabolic events occurring during recovery from prolonged glucose starvation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1968 Mar;95(3):1030–1039. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.3.1030-1039.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John A., Isaacson H. R., Bryant M. P. Isolation and characteristics of a ureolytic strain of Selenomonas ruminatium. J Dairy Sci. 1974 Sep;57(9):1003–1014. doi: 10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(74)85001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. R. Influence of carbohydrate solubility on non-protein nitrogen utilization in the ruminant. J Anim Sci. 1976 Jul;43(1):184–191. doi: 10.2527/jas1976.431184x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch A. L. The adaptive responses of Escherichia coli to a feast and famine existence. Adv Microb Physiol. 1971;6:147–217. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leedle J. A., Hespell R. B. Differential carbohydrate media and anaerobic replica plating techniques in delineating carbohydrate-utilizing subgroups in rumen bacterial populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980 Apr;39(4):709–719. doi: 10.1128/aem.39.4.709-719.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathison G. W., Milligan L. P. Nitrogen metabolism in sheep. Br J Nutr. 1971 May;25(3):351–366. doi: 10.1079/bjn19710100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mink R. W., Hespell R. B. Long-term nutrient starvation of continuously cultured (glucose-limited) Selenomonas ruminantium. J Bacteriol. 1981 Nov;148(2):541–550. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.2.541-550.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague M. D., Dawes E. A. The survival of Peptococcus prévotii in relation to the adenylate energy charge. J Gen Microbiol. 1974 Jan;80(1):291–299. doi: 10.1099/00221287-80-1-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan J. V., Norton B. W., Leng R. A. Nitrogen cycling in sheep. Proc Nutr Soc. 1973 Sep;32(2):93–98. doi: 10.1079/pns19730021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POSTGATE J. R., HUNTER J. R. The survival of starved bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1962 Oct;29:233–263. doi: 10.1099/00221287-29-2-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paynter M. J., Elsden S. R. Mechanism of propionate formation by Selenomonas ruminantium, a rumen micro-organism. J Gen Microbiol. 1970 Apr;61(1):1–7. doi: 10.1099/00221287-61-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim A. F., Weller R. A., Gray F. V., Belling C. B. Synthesis of microbial protein from ammonia in the sheep's rumen and the proportion of dietary nitrogen converted into microbial nitrogen. Br J Nutr. 1970 Jun;24(2):589–598. doi: 10.1079/bjn19700057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece P., Toth D., Dawes E. A. Fermentation of purines and their effect on the adenylate energy charge and viability of starved Peptococcus prévotii. J Gen Microbiol. 1976 Nov;97(1):63–71. doi: 10.1099/00221287-97-1-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salanitro J. P., Muirhead P. A. Quantitative method for the gas chromatographic analysis of short-chain monocarboxylic and dicarboxylic acids in fermentation media. Appl Microbiol. 1975 Mar;29(3):374–381. doi: 10.1128/am.29.3.374-381.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheifinger C. C., Wolin M. J. Propionate formation from cellulose and soluble sugars by combined cultures of Bacteroides succinogenes and Selenomonas ruminantium. Appl Microbiol. 1973 Nov;26(5):789–795. doi: 10.1128/am.26.5.789-795.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. J., Hespell R. B., Bryant M. P. Ammonia assimilation and glutamate formation in the anaerobe Selenomonas ruminantium. J Bacteriol. 1980 Feb;141(2):593–602. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.2.593-602.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange R. E. Bacterial "glycogen" and survival. Nature. 1968 Nov 9;220(5167):606–607. doi: 10.1038/220606a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T. D., Batt R. D. Degradation of cell constituents by starved Streptococcus lactis in relation to survival. J Gen Microbiol. 1969 Nov;58(3):347–362. doi: 10.1099/00221287-58-3-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T. D., Batt R. D. Metabolism of exogenous arginine and glucose by starved Streptococcus lactis in relation to survival. J Gen Microbiol. 1969 Nov;58(3):371–380. doi: 10.1099/00221287-58-3-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T. D., Batt R. D. Survival of Streptococcus lactis in starvation conditions. J Gen Microbiol. 1968 Mar;50(3):367–382. doi: 10.1099/00221287-50-3-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace R. J. Control of lactate production by Selenomonas ruminantium: homotropic activation of lactate dehydrogenase by pyruvate. J Gen Microbiol. 1978 Jul;107(1):45–52. doi: 10.1099/00221287-107-1-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace R. J. Cytoplasmic reserve polysaccharide of Selenomonas ruminantium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980 Mar;39(3):630–634. doi: 10.1128/aem.39.3.630-634.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright D. E., Hungate R. E. Amino acid concentrations in rumen fluid. Appl Microbiol. 1967 Jan;15(1):148–151. doi: 10.1128/am.15.1.148-151.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]