Abstract

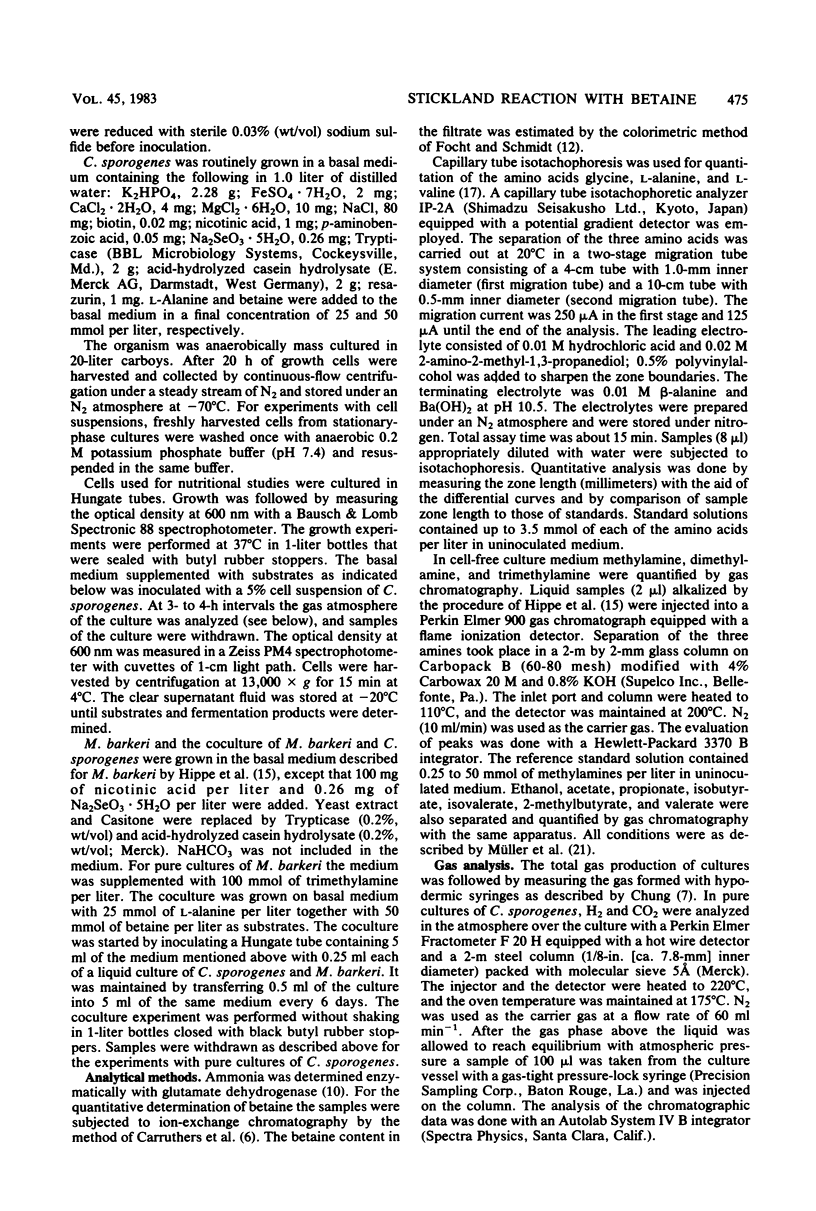

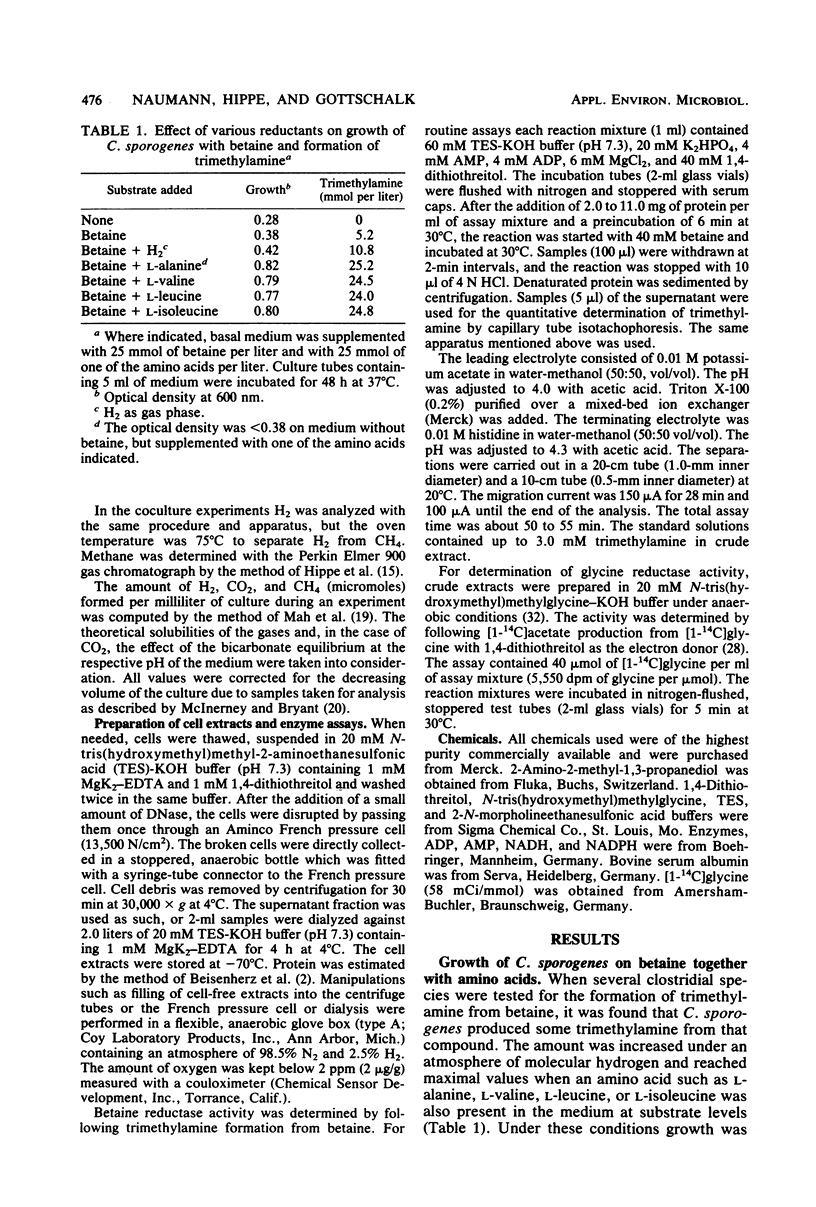

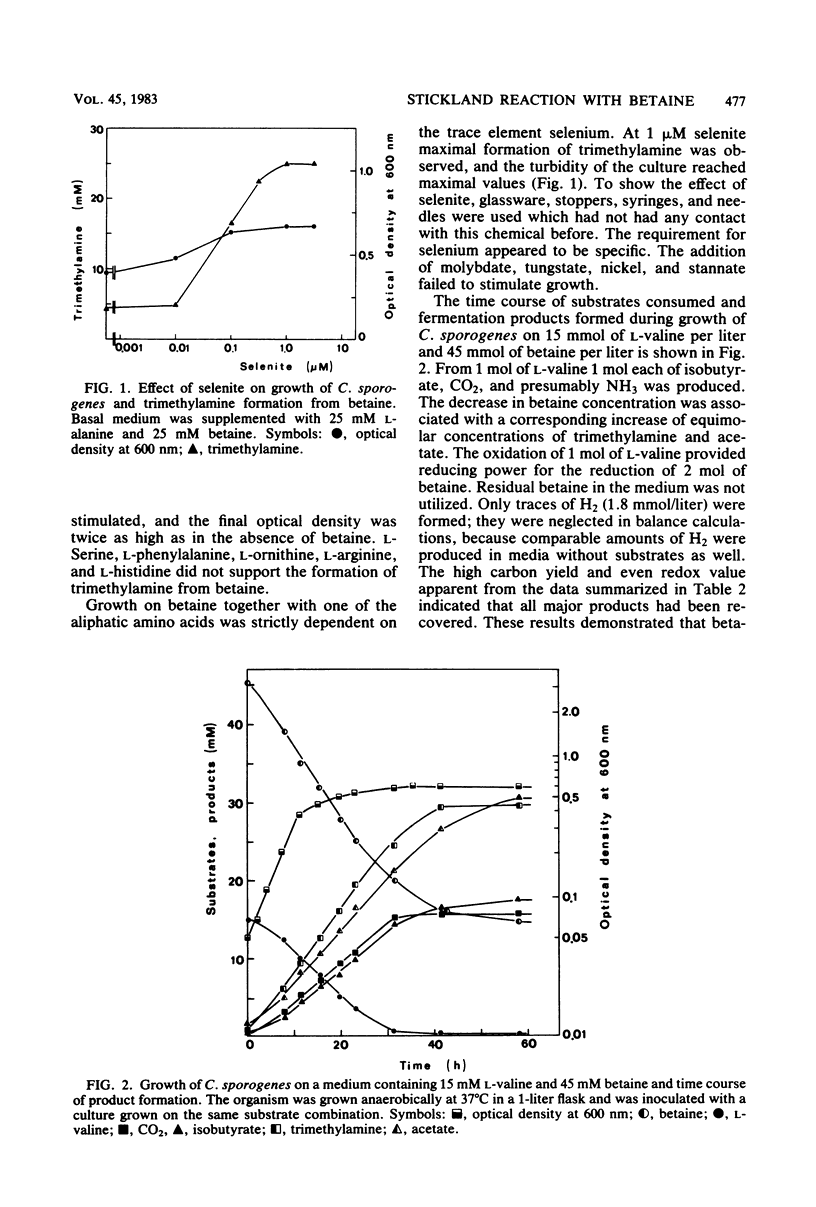

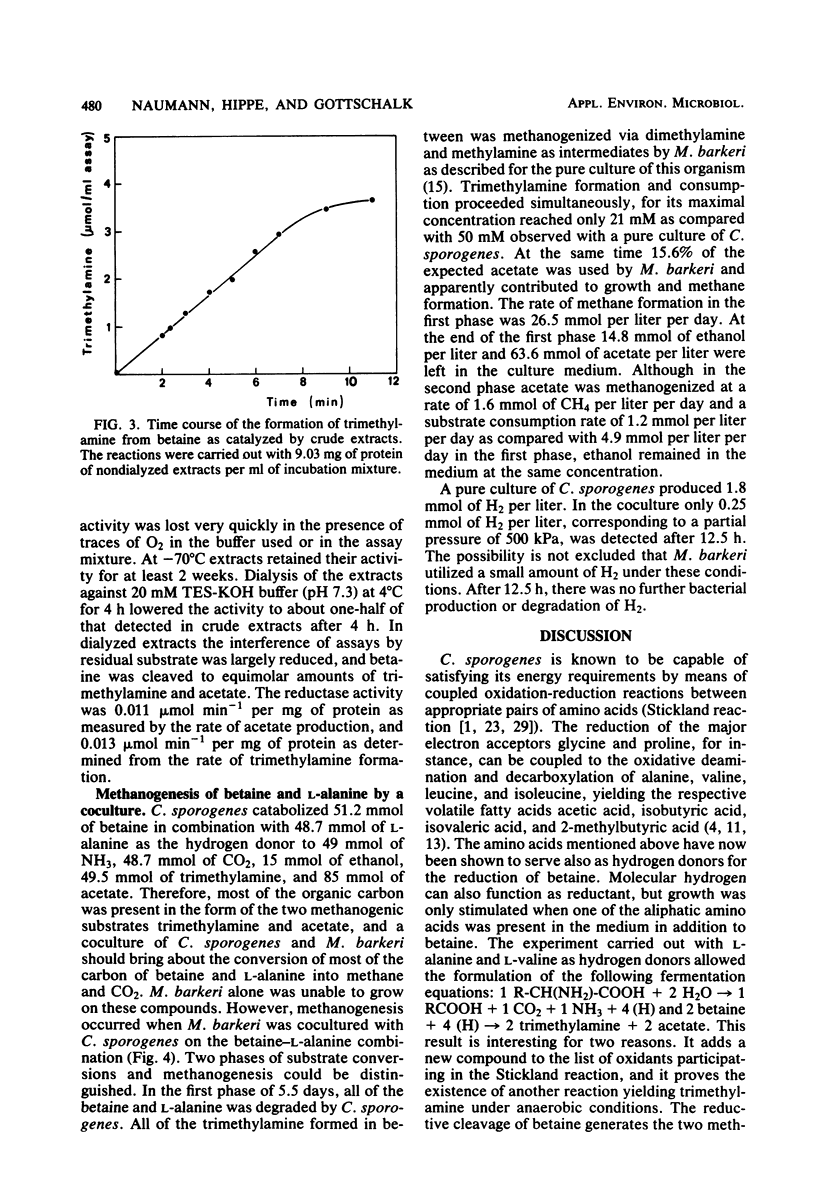

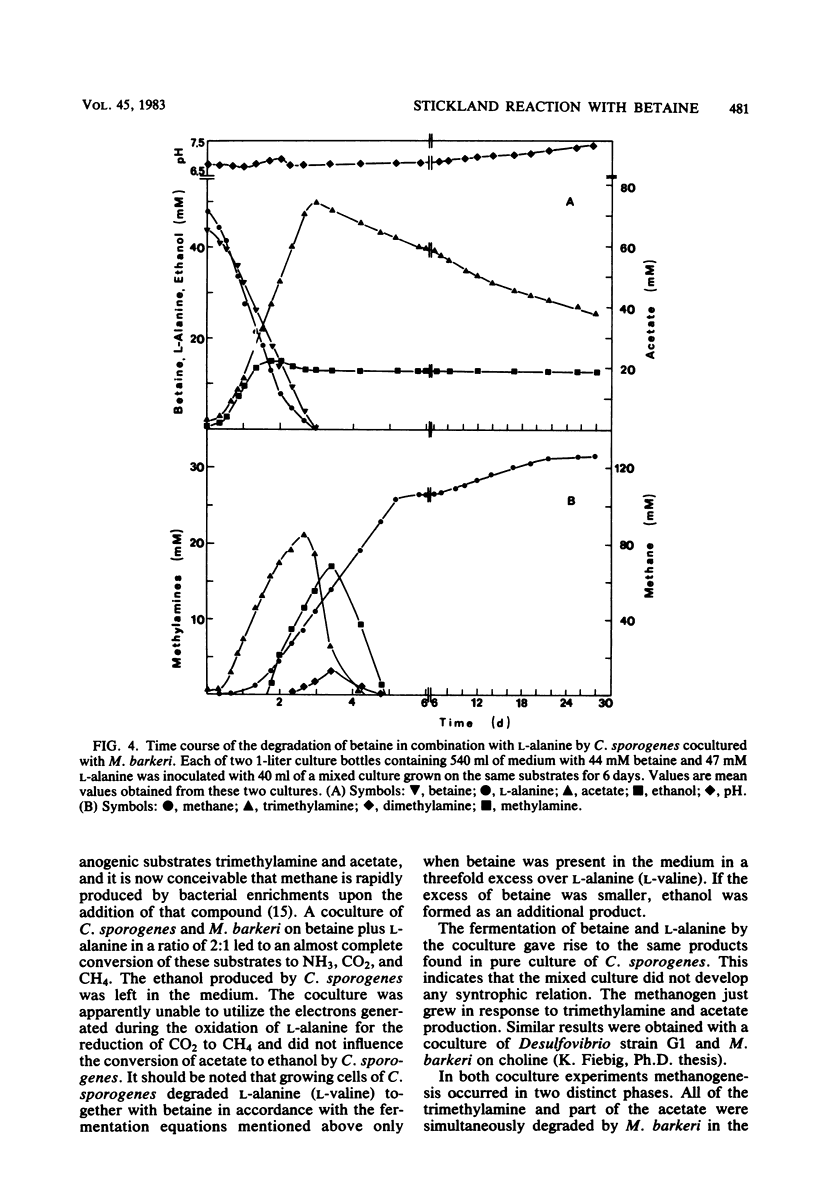

Growing and nongrowing cells of Clostridium sporogenes fermented betaine with l-alanine, l-valine, l-leucine, and l-isoleucine as electron donors in a coupled oxidation-reduction reaction (Stickland reaction). For the substrate combinations betaine and l-alanine and betaine and l-valine balance studies were performed; the results were in agreement with the following fermentation equation: 1 R- CH(NH2)-COOH + 2 betaine + 2 H2O → 1 R-COOH + 1 CO2 + 1 NH3 + 2 trimethylamine + 2 acetate. Growth and production of trimethylamine were strictly dependent on the presence of selenite in the medium. With cell suspensions it was shown that C. sporogenes was unable to catabolize betaine as a single substrate. Betaine, however, was reduced to trimethylamine and acetate under an atmosphere of molecular hydrogen. For the reduction of betaine by cell extracts of C. sporogenes, dimercaptans such as 1,4-dithiothreitol could serve as electron donors. No betaine reductase activity was detected in cells grown in a complex medium without betaine. The pH optimum of betaine reductase was at pH 7.3. When C. sporogenes was cocultured with Methanosarcina barkeri strain Fusaro on betaine together with l-alanine, an almost complete conversion of the two substrates to CH4, NH3, and presumably CO2 was observed.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bradbeer C. The clostridial fermentations of choline and ethanolamine. 1. Preparation and properties of cell-free extracts. J Biol Chem. 1965 Dec;240(12):4669–4674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britz M. L., Wilkinson R. G. Leucine dissimilation to isovaleric and isocaproic acids by cell suspensions of amino acid fermenting anaerobes: the Stickland reaction revisited. Can J Microbiol. 1982 Mar;28(3):291–300. doi: 10.1139/m82-043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant M. P. Commentary on the Hungate technique for culture of anaerobic bacteria. Am J Clin Nutr. 1972 Dec;25(12):1324–1328. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/25.12.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K. T. Inhibitory effects of H2 on growth of Clostridium cellobioparum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1976 Mar;31(3):342–348. doi: 10.1128/aem.31.3.342-348.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone J. E., del Río R. M., Stadtman T. C. Clostridial glycine reductase complex. Purification and characterization of the selenoprotein component. J Biol Chem. 1977 Aug 10;252(15):5337–5344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costilow R. N. Selenium requirement for the growth of Clostridium sporogenes with glycine as the oxidant in stickland reaction systems. J Bacteriol. 1977 Jul;131(1):366–368. doi: 10.1128/jb.131.1.366-368.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsden S. R., Hilton M. G. Volatile acid production from threonine, valine, leucine and isoleucine by clostridia. Arch Microbiol. 1978 May 30;117(2):165–172. doi: 10.1007/BF00402304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer T. F., Mead G. C. Development of a selective medium for the isolation of Clostridium sporogenes and related organisms. J Appl Bacteriol. 1979 Dec;47(3):425–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1979.tb01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYWARD H. R., STADTMAN T. C. Anaerobic degradation of choline. I. Fermentation of choline by an anaerobic, cytochrome-producing bacterium, Vibrio cholinicus n. sp. J Bacteriol. 1959 Oct;78:557–561. doi: 10.1128/jb.78.4.557-561.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippe H., Caspari D., Fiebig K., Gottschalk G. Utilization of trimethylamine and other N-methyl compounds for growth and methane formation by Methanosarcina barkeri. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Jan;76(1):494–498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutten T. J., Bongaerts H. C., van der Drift C., Vogels G. D. Acetate, methanol and carbon dioxide as substrates for growth of Methanosarcina barkeri. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1980;46(6):601–610. doi: 10.1007/BF00394016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopwillem A., Moberg U., Westin-Sjödahl G., Lundin R., Sievertsson H. Analytical isotachophoresis in the analysis of synthetic peptides. Anal Biochem. 1975 Jul;67(1):166–181. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzycki J. A., Wolkin R. H., Zeikus J. G. Comparison of unitrophic and mixotrophic substrate metabolism by acetate-adapted strain of Methanosarcina barkeri. J Bacteriol. 1982 Jan;149(1):247–254. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.1.247-254.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah R. A., Smith M. R., Baresi L. Studies on an acetate-fermenting strain of Methanosarcina. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978 Jun;35(6):1174–1184. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.6.1174-1184.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInerney M. J., Bryant M. P. Anaerobic Degradation of Lactate by Syntrophic Associations of Methanosarcina barkeri and Desulfovibrio Species and Effect of H(2) on Acetate Degradation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981 Feb;41(2):346–354. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.2.346-354.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller E., Fahlbusch K., Walther R., Gottschalk G. Formation of N,N-Dimethylglycine, Acetic Acid, and Butyric Acid from Betaine by Eubacterium limosum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981 Sep;42(3):439–445. doi: 10.1128/aem.42.3.439-445.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISMAN B. The Stickland reaction. Bacteriol Rev. 1954 Mar;18(1):16–42. doi: 10.1128/br.18.1.16-42.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickland L. H. Studies in the metabolism of the strict anaerobes (genus Clostridium): The chemical reactions by which Cl. sporogenes obtains its energy. Biochem J. 1934;28(5):1746–1759. doi: 10.1042/bj0281746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strøm A. R., Olafsen J. A., Larsen H. Trimethylamine oxide: a terminal electron acceptor in anaerobic respiration of bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1979 Jun;112(2):315–320. doi: 10.1099/00221287-112-2-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H., Stadtman T. C. Selenium-dependent clostridial glycine reductase. Purification and characterization of the two membrane-associated protein components. J Biol Chem. 1979 Jan 25;254(2):447–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimer P. J., Zeikus J. G. Acetate metabolism in Methanosarcina barkeri. Arch Microbiol. 1978 Nov 13;119(2):175–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00964270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimer P. J., Zeikus J. G. One carbon metabolism in methanogenic bacteria. Cellular characterization and growth of Methanosarcina barkeri. Arch Microbiol. 1978 Oct 4;119(1):49–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00407927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinder S. H., Mah R. A. Isolation and Characterization of a Thermophilic Strain of Methanosarcina Unable to Use H(2)-CO(2) for Methanogenesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979 Nov;38(5):996–1008. doi: 10.1128/aem.38.5.996-1008.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]