Abstract

Transmembrane glutamate transport by the excitatory amino acid carrier (EAAC1) is coupled to the cotransport of three Na+ ions and one proton. Previously, we suggested that the mechanism of H+ cotransport involves protonation of the conserved glutamate residue E373. However, it was also speculated that the cotransported proton is shared in a H+-binding network, possibly involving the conserved histidine 295 in the 6th transmembrane domain of EAAC1. Here, we used site-directed mutagenesis together with pre-steady state electrophysiological analysis of the mutant transporters in order to test the protonation state of H295 and to determine its involvement in proton transport by EAAC1. Our results show that replacement of H295 with glutamine, an amino acid residue that can not be protonated, generates a fully functional transporter with transport kinetics that are close to the wild-type EAAC1. In contrast, replacement with lysine results in a transporter in which substrate binding and translocation are dramatically inhibited. Furthermore, it is demonstrated that the effect of the histidine 295 to lysine mutation on the glutamate affinity is caused by its positive charge, since wild-type-like affinity can be restored by changing the extracellular pH to 10.0, thus partially deprotonating H295K. Together, these results suggest that histidine 295 is not protonated in EAAC1 at physiological pH, and, thus, does not contribute to H+ cotransport. This conclusion is supported by data from H295C-E373C double mutant transporters which demonstrate that these residues can not be linked by oxidation, indicating that H295 and E373 are not close in space and do not form a proton binding network. A kinetic scheme is used to quantify the results, which includes binding of the cotransported proton to E373 and binding of a modulatory, non-transported proton to the amino acid side chain in position 295.

Keywords: Glutamate, excitatory amino acid transporter, EAAC1, glutamate transporter, mutagenesis, pre-steady-state kinetics

The plasma membrane glutamate transporters belong to the class of sodium-dependent secondary transport proteins. They transport glutamate into the cell against its own transmembrane concentration gradient by coupling to the downhill movement of Na+ and K+ ions across the membrane (1, 2). In addition, it was shown that inward glutamate transport is associated with intracellular acidification, suggesting that protons are cotransported together with glutamate (3–5).

The mechanism of directional proton transport by the glutamate transporter subtype EAAC1 is thought to be as follows: H+ associates with the transport protein in the absence of the substrate glutamate (6–8). Glutamate can only bind to the protonated form of the carrier. Once glutamate is bound to this form, translocation takes place to expose the binding sites for H+ and glutamate to the intracellular side (6). After dissociation of glutamate and H+ to the cytoplasm, the transporter relocates its binding sites in its basic, unprotonated form. This mechanism requires the presence of a proton acceptor on the protein that can switch its pKa as the transporter moves through the transport cycle (6). Based on kinetic data, we had previously excluded a model in which the cotransported proton is attached to the negatively charged glutamate, once it is bound to the transporter (6).

Recently, we suggested that the proton acceptor of EAAC1 is the side chain carboxylate of a glutamate residue in position 373 (E373, EAAC1 numbering, (8)), which is localized in the 8th transmembrane segment of EAAC1 (Figure 1A). E373 was identified as a candidate because in the related neutral amino acid transporters ASCT1 and ASCT2, which do not transport protons, the amino acid in the location homologous to E373 is a non-protonatable glutamine (9, 10). In addition to acidic amino acid side chains, histidine residues have been implicated in proton transport by secondary transporters, such as the lac-permease (11, 12), the Na+/H+-antiporter (13, 14), and the peptide transporters (15). Glutamate transporters contain a conserved histidine residue in position 295 (EAAC1 numbering) which is thought to be localized within the 6th hydrophobic transmembrane segment of the transporter (Figure 1A). It was shown previously that mutation of H295 to arginine, lysine, or neutral amino acids (asparagine and threonine) resulted in a non-functional transport protein (16). Based on these data, it was suggested that H295 is critical for the function of the transporter and that it may be involved in proton cotransport.

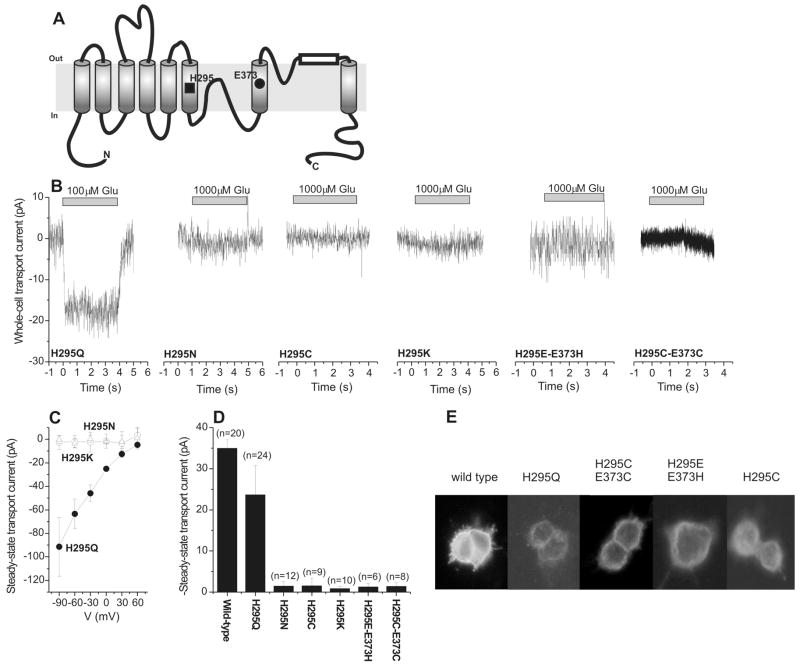

Figure 1.

(A) Topology model adapted from (32) showing the putative location of the mutated residues H295 and E373. (B) Typical transport current recordings of mutant glutamate transporters after application of the glutamate concentration indicated at the bar. The transmembrane potential was 0 mV, the pipette contained 140 mM KCl. (C) Voltage dependence of the steady-state transport currents induced by application of 100 μM glutamate to EAAC1H295Q and EAAC1H295N, and 1 mM glutamate to EAAC1H295K. (D) Statistical analysis of transport currents shown in (B). n represents the number of cells used for data averaging. (E) Immunocytochemistry of wild-type and mutant glutamate transporters.

Here, we present new data on EAAC1 function after replacing histidine 295 with amino acids with either neutral or basic (positively charged) side chains, showing that H295 is not involved in proton cotransport. Although glutamate and the cotransported H+ can still bind to EAAC1H295N and EAAC1H295C, subsequent reactions, such as glutamate translocation, are strongly inhibited in the mutant transporters. In contrast, the function of EAAC1H295Q is indistinguishable from that of the wild type transporter. All together, our results indicate that H295 is not protonated at physiological pH and, thus, does not contribute to proton cotransport by EAAC1. However, substitution of H295 with a basic lysine residue leads to the introduction of a second protonation site in position 295 which, upon protonation, modulates the apparent affinity of the transporter for glutamate.

Materials and Methods

Molecular Biology and Transient Expression

Wild-type EAAC1 cloned from rat retina was subcloned into pBK-CMV (Stratagene) as described previously (17) and was used for site-directed mutagenesis according to the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) as described by the supplier. The primers for mutation experiments were obtained from the DNA core lab, Department of Biochemistry at the University of Miami School of Medicine. The complete coding sequences of mutated EAAC1 clones were subsequently sequenced. Wild-type and mutant EAAC1 constructs were used for transient transfection of sub-confluent human embryonic kidney cell (HEK293, ATCC number CGL 1573 or HEK293T/17, ATCC number CRL 11268) cultures using the calcium phosphate-mediated transfection method (18) as described previously (17). The 293T/17 cell line is a derivative of the 293T cell line into which the gene for SV40 T-antigen was inserted. Electrophysiological recordings were performed between days 1 to 3 post-transfection.

Immunofluorescence

Immunostaining of EAAC1-expressing cells was performed as follows: Transfected HEK293 cells plated on poly-D-lysine-coated coverslips were washed two times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then fixed in 3% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in PBS for 25 min at room temperature (RT). After several washing steps with PBS, the cells were permeabilized in 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS at RT for 10 min. After a washing step with PBS, they were blocked with 0.2% (w/v) BSA in PBS for 30 min at RT and then incubated with 0.01 mg/ml affinity-purified EAAC1 antibody (Alpha Diagnostics) in 0.5% (w/v) BSA, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 hour at RT. Following primary antibody incubation, the cells were rinsed and incubated (1 h) with anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Cy3 (1:500, Dianova, Germany) in PBS containing 0.5% (w/v) BSA, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100. After washing with PBS and water the cells were mounted with antifade reagent (Molecular Probes) and stored in the dark. The Cy3 immunofluorescence was excited with a mercury lamp, visualized with an inverted microscope (Zeiss) by using a TMR filterset (Omega) and photographed with a digital camera (Canon).

Electrophysiology

Glutamate-induced EAAC1 currents were recorded with an Adams & List EPC7 amplifier under voltage-clamp conditions in the whole-cell current-recording configuration. The typical resistance of the recording electrode was 2–3 M3; the series resistance was 5–8 M3. Because the glutamate-induced currents were small (typically < 500 pA), series resistance (RS) compensation had a negligible effect on the magnitude of the observed currents (< 4% error). Therefore, RS was not compensated. The extracellular solution contained (in mM): 140 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, and 30 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES). Two different pipette solutions were used depending on whether mainly the non-coupled anion current (with thiocyanate) or the coupled transport current (with chloride) was investigated (19). These solutions contained (in mM): 130 KSCN or KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 tetraethyl-ammonium chloride (TEACl), 10 ethylene glycol-bis-(beta-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetracetic acid (EGTA), and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4/KOH). Thiocyanate was used because it enhances glutamate transporter associated currents and allows the detection of the EAAC1 anion-conducting mode (19).

For the electrophysiological investigation of the Na+/glutamate homoexchange mode the pipette solution contained (in mM) 140 NaCl/NaSCN, 2 MgCl2, 10 TEACl, 10 EGTA, 10 glutamate, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4/NaOH). In this transport mode, the same concentrations of Na+ are used on both sides of the membrane, and concentrations of glutamate are used on the intra- and extracellular side which saturate their respective binding site. The affinity of EAAC1 for cytoplasmic glutamate is 280 μM (6). Therefore, we used 10 mM cytoplasmic glutamate in order to ensure saturation of the intracellular binding site. In contrast the affinity for extracellular glutamate is about 6 μM (17) and 100 – 200 μM extracellular glutamate is sufficient for saturation of this binding site. Initially, glutamate was omitted from the extracellular solution. Under these conditions, the high intracellular Na+ and glutamate concentrations will drive the majority of glutamate binding sites to face the extracellular side. Subsequently, application of extracellular glutamate resulted in a redistribution of these binding sites to reach a new steady state. According to the nature of the exchange mode it is not associated with steady-state transport current. However, transient transport currents were observed when glutamate was applied to the extracellular side of the membrane, due to the electrogenic redistribution of Na+ and glutamate binding sites within the membrane (20). When permeating anions, such as SCN−, are present establishment of homoexchange conditions leads to the permanent activation of an anion current (20, 21). This permanent anion current was used in this work as a tool to study the behavior of mutant transporters in the homoexchange mode.

The currents were low pass filtered at 1–10 kHz (Krohn-Hite 3200), and digitized with a digitizer board (Axon, Digidata 1200) at a sampling rate of 10–50 kHz, which was controlled by software (Axon PClamp). All the experiments were performed at room temperature.

Laser-Pulse Photolysis and Rapid Solution Exchange

Rapid solution exchange was performed as described previously (17). Briefly, substrates were applied to the EAAC1-expressing cell by means of a quartz tube (opening diameter: 350 μm) positioned at a distance of ~0.5 mm to the cell. The linear flow rate of the solutions emerging from the opening of the tube was ~5–10 cm/s, resulting in typical rise times of the whole-cell current of 30–50 ms (10–90%). Laser-pulse photolysis experiments were performed according to previous studies (17, 20). 4-methoxy-7-nitroindolinyl- (MNI)-caged glutamate ((22) Tocris) in concentrations of 1~4 mM or free glutamate were applied to the cells and photolysis of the caged glutamate was initiated with a light flash (340 nm, 15 ns, excimer laser pumped dye laser, Lambda Physik, Göttingen, Germany). The light was coupled into a quartz fiber (diameter, 365 μm) that was positioned at a distance of 300 μm from the cell. The laser energy was adjusted with neutral density filters (Andover Corp.). With maximum light intensities of 500–600 mJ/cm2 saturating glutamate concentrations could be released, which was tested by comparison of the steady-state current with that generated by rapid perfusion of the same cell with a glutamate concentration that saturated the respective mutant transporter. In rare cases HEK293 cells respond to the laser flash with small transient current responses (< 10 pA) in the absence of caged compound. Such cells were discarded.

Data Analysis

Non-linear regression fits of experimental data were performed with Origin (Microcal software, Northampton, MA) or Clampfit (pClamp8 software, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Pre-steady-state currents were fitted with sums of two or three exponential terms. Dose response relationships of currents were fitted with a Michaelis-Menten-like equation, yielding Km and Imax. Charge movement was obtained by integrating the current traces. The voltage dependence of the fast charge movement (Qfast) was fitted with a Boltzmann-like equation:

| (1) |

In this equation, Qmax is the maximum charge movement, V1/2 is the potential where half of the charge movement occurred, and zapp is its apparent valence.

For simulating the pH dependence of the Km of the wild-type transporter for glutamate we used the previously established model of protonation of the glutamate-free transporter (6). The equation used was:

| (2) |

Here, Km is the apparent dissociation constant of glutamate from the transporter, KG is the intrinsic dissociation constant for glutamate, and KH1 is the dissociation constant of the cotransported proton from E373.

For EAAC1H295K-E373Q, it was assumed that E373Q is permanently protonated and protonation can only occur at H295K. The equation derived corresponding to the model shown in Figure 6A is:

| (3) |

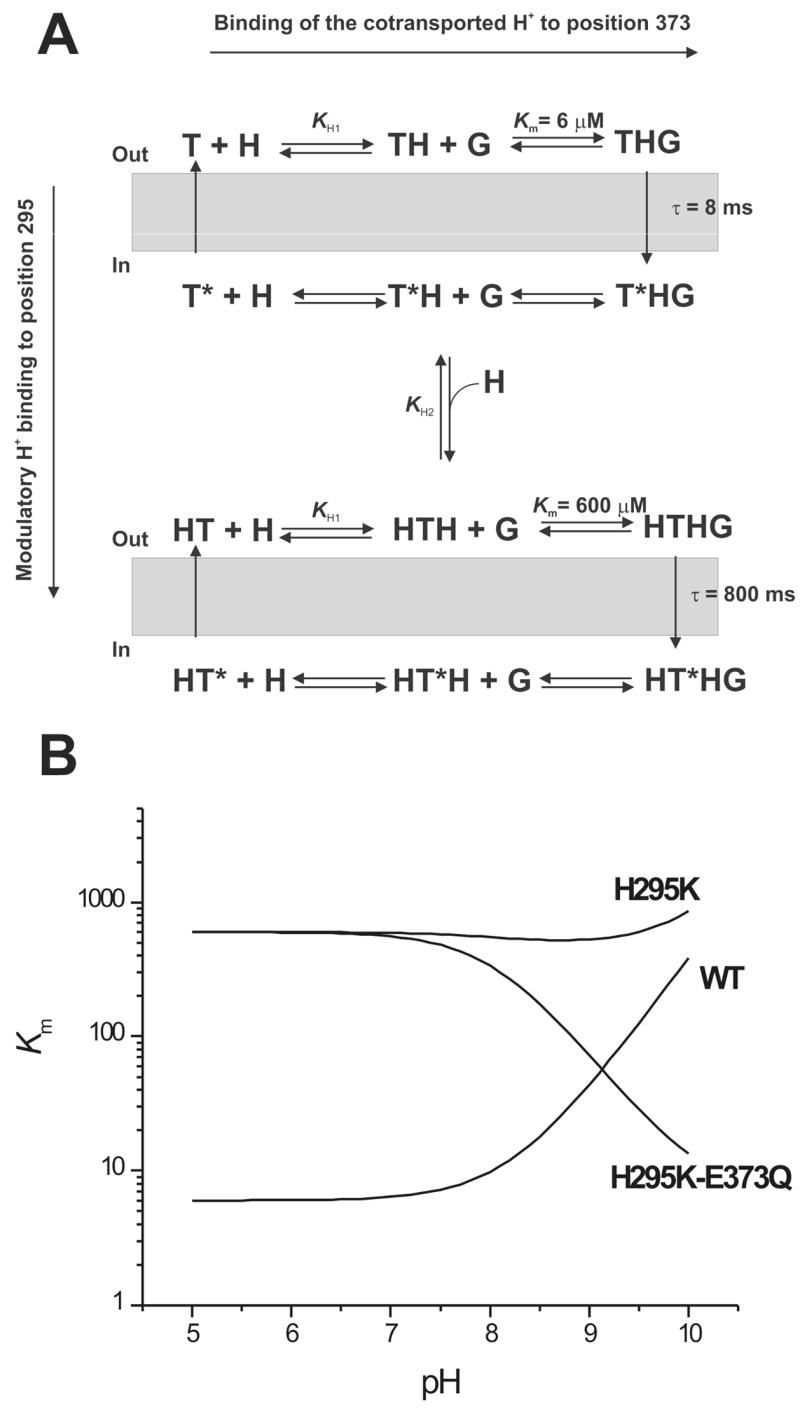

Figure 6.

(A) Kinetic model of the effect of protonation in position 295 on glutamate transport by EAAC1. The empty transporter (T) binds the cotransported proton (H) at E373, forming TH. Subsequently, glutamate (G) binds to form THG, the fully loaded transporter (horizontal axis). The respective states with their substrate binding sites exposed to the intracellular side are marked with a star (*). Protonation by the modulatory H+ in position 295 (vertical axis) results in a transporter cycle with altered glutamate binding properties and translocation kinetics. (B) Simulation of the pH dependence of the Km for glutamate for the wild-type and the H295K and H295K-E373Q mutant transporters, according to the model shown in (A). The equations used for the simulations are described in the Materials and Methods section. The parameters used were: Km(WT) = 6 μM, Km(H295K) = 600 μM, pKa(E373) = 8.2, pKa (H295K) = 10.1. For table of contents use only Manuscript title: The conserved histidine 295 does not contribute to proton cotransport by the glutamate transporter EAAC1. Authors: Zhen Tao and Christof Grewer

Here, KG1 is the intrinsic dissociation constant for glutamate from the transporter with a neutral sidechain in position H295, and KG2 is the intrinsic dissociation constant for glutamate from the transporter with the modulatory proton bound to H295K. KH2 is the dissociation constant of the modulatory proton from H295K.

For EAAC1H295K, it was assumed that the transporter can be protonated in two positions, E373 and H295K. The equation derived corresponding to Figure 6 is:

| (4) |

In this equation, KH1 is the dissociation constant of the cotransported proton from E373 and, KH2 is the dissociation constant of the non-transported, modulatory proton from H295K. To derive eq. 4, we assumed that glutamate and proton binding are fast compared to translocation (pre-equilibrium conditions), and that translocation takes place only from state THG in the scheme shown in Figure 6. Under these conditions, the fractional population of state THG will be a direct measure of the observed current. The apparent Km for glutamate can then be directly derived from the expression of the fractional population of state THG as a function of the glutamate concentration.

Results

Glutamate transporters with amino acid substitutions in position 295 were expressed in HEK293 or HEK293T/17 cells and were functionally characterized by whole-cell current recording. In order to test the protonation state of H295, we investigated mutant transporters in which H295 was exchanged with amino acids with neutral side chains (glutamine, asparagine, and cysteine), presumably substituting for a non-protonated histidine, or with a sidechain with putative positive charge (lysine), substituting for a protonated histidine.

Steady-state properties

Typical current measurements of the mutant transporters after application of saturating concentrations of glutamate by using a rapid solution exchange method are shown in Figure 1B (all at 0 mV transmembrane potential). The steady-state transport currents observed for the mutant transporters with neutral side chain in position 295 were negligible (within experimental error), except for EAACH295Q (Figure 1B, Table 1). EAAC1H295K, which has a positively-charged side chain in position 295, also showed negligible glutamate-induced steady-state transport current. The results obtained from all the mutants and the wild-type transporter are summarized in Figure 1D. We next asked the question whether steady-state transport current in the mutant transporters is absent at 0 mV voltage because of a shift in the voltage dependence of EAAC1 glutamate transport by the mutations. To answer this question, we determined the voltage dependence of steady-state glutamate transport of the H295Q, H295N, and H295K mutant transporters, as shown in Figure 1C. EAACH295Q shows a voltage dependence of the transport current that is very similar to that of the wild-type transporter: The more negative the voltage, the stronger the current becomes (17). In contrast, EAACH295N, EAACH295C and EAACH295K do not catalyze steady-state transport current even at the most negative voltage tested (−90 mV).

Table 1.

Steady-state kinetic parameters of wild-type and H295-mutant EAAC1 transporters. Km is the apparent affinity for glutamate in the forward transport mode (WT and H295Q) or the homoexchange mode for the other mutant transporters. Itransport was determined at saturating glutamate concentrations. All the values were averaged from data collected from at least three cells.

| Mutants | WT | H295Q | H295N | H295K | H295E-E373H | H295C-E373C | H295C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (μM) | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 6.8 ± 2.5 | 48 ± 4 | 600 ± 60 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 89.7 ± 4.4 | 14.9 ±14 |

| Itransport(pA) | 35 ± 2 | 24 ± 7 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 |

The absence of transport current in EAACH295N, EAACH295C and EAACH295K is not caused by impaired expression or targeting to the plasma membrane. Immunocytochemical experiments shown in Figure 1E demonstrate that all of the mutant transporters are expressed in HEK293 cells and that their expression pattern is similar to that of the wild-type transporter, showing immunostaining of cell regions close to or in the plasma membrane and no increased accumulation in intracellular compartments. Differences in the level of immunofluorescence between EAAC1WT and the mutant transporters are probably not directly related to differences in expression levels, since we have shown previously by electrophysiological analysis that expression levels of EAAC1 can vary up to 5-fold between transfected HEK293 cells of the same culture (17).

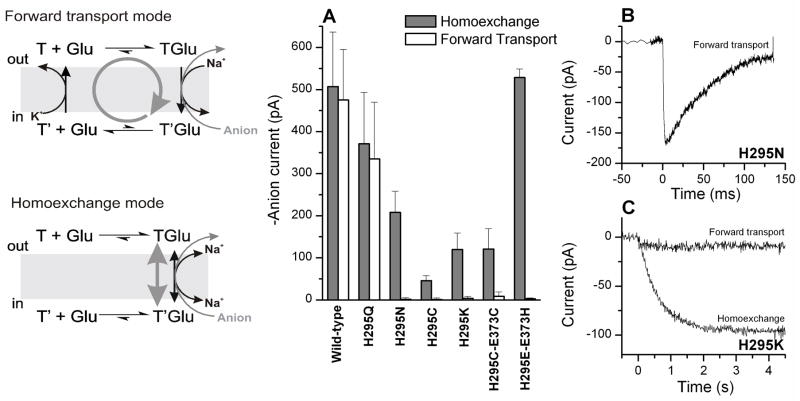

To further demonstrate localization of the mutant transporters in the plasma membrane, we conducted current recording experiments in the anion conducting mode of the transporter. The rationale of these experiments was that it had been shown previously for several other mutant glutamate transporters that they can catalyze anion current through the transporter-associated anion conductance in the total absence of functional glutamate uptake (7, 8, 23). For EAAC1H295Q and wild-type EAAC1, steady-state inward anion current was observed upon glutamate application in the forward transport mode (illustrated in the left panel of Figure 2), with K+ being the only intracellular cation driving transport (n = 4, Figure 2A, current traces not shown). In contrast, EAACH295N, EAACH295C and EAACH295K catalyzed only very little anion current in the forward transport mode (IH295N = 1.5 ± 4 pA (n = 6); IH295C = −1.4 ± 1.3 pA (n = 4); IH295K = 4 ± 5 pA (n = 4)). However, glutamate application to EAACH295N, EAACH295C and EAACH295K in the homoexchange mode (saturating concentrations of glutamate and sodium ions on both sides of the membrane in the absence of K+) resulted in large, inwardly-directed anion currents in the range of −50 to −500 pA (summarized in Figure 2A). These currents were caused by SCN− leaving the cell since for none of the mutant and wild-type transporters steady-state currents were observed in the homoexchange mode in the absence of permeating anions (data not shown, but see also (20) for EAAC1WT data). In the homoexchange mode, the transporter is restricted to reside in states associated with the Na+/glutamate translocation branch of the transport cycle (illustrated in the left panel of Figure 2). Therefore, even in the mutant transporters which do not catalyze forward transport, steady-state anion current is observed under homoexchange conditions because states fully loaded with Na+ and glutamate are anion-conducting (17, 24). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the mutated transporters are functionally expressed in the plasma membrane, and can bind and probably translocate glutamate into the cell. However, steady-state transport is impaired and, therefore, no steady-state transport and anion currents were detected for these mutant transporters in the forward transport mode.

Figure 2.

Anion currents catalyzed by H295 mutant transporters in the forward transport mode and in the homoexchange mode. The left panel illustrates the catalytic cycle for each transport mode. The thick grey arrow indicates the major direction of the transport reaction. (A) Steady-state anion currents generated by saturating glutamate concentrations in H295 mutant transporters in the forward transport mode (140 mM KSCN internal, white bars), and homoexchange mode (140 mM NaSCN, 10 mM glutamate internal, grey bars). The transmembrane potential was 0 mV. (B) Anion current induced by the flash-photolytic application of 0.2 mM glutamate to EAAC1H295N-expressing HEK293 cells in the forward transport mode (140 mM KSCN internal). The transmembrane potential was 0 mV. (C) Anion currents induced by the rapid flow application of 1 mM glutamate to EAAC1H295K-expressing HEK293 cells in the forward transport mode (140 mM KSCN internal), and homoexchange mode (140 mM NaSCN, 10 mM glutamate internal). The transmembrane potential was 0 mV. Note the different time scales in (B) and (C).

The amplitudes of anion currents carried by the mutant transporters in the homoexchange mode depended on the glutamate concentration in a Michaelis-Menten-like fashion, allowing us to determine apparent affinities (Km) of the mutant transporters for glutamate. The apparent Km of EAACH295Q was similar to that of the EAACWT, while the Km values of EAACH295N, EAACH295C and EAACH295K were 3- to 120-times larger than that of EAACWT (summarized in Table 1). The histidine to lysine substitution had the most pronounced effect on Km, resulting in an apparent affinity for glutamate of 600 ± 60 μM.

Pre-steady-state kinetics

We first performed pre-steady-state experiments in the anion conducting mode. EAAC1H295Q showed pre-steady-state currents upon rapid application of ~ 100 μM glutamate by photolysis from 1 mM of the MNI-caged precursor which were similar in kinetics to those of the wild-type transporter ((17, 19), data not shown). In the presence of intracellular KSCN (forward transport mode, illustrated in the left panel of Figure 2) the currents exhibited a distinct transient current component that decayed to a steady state with a time constant of 10.0 ± 0.1 ms. Under the same conditions, no steady-state component was observed for EAAC1H295N, but a large transient inward current was present which decayed with a time constant of 190 ± 40 ms (Figure 2B). This behavior is reminiscent of the wild-type transporter in the absence of intracellular K+, indicating that K+-dependent reaction steps in the transport cycle are impaired (17). The steady-state anion current component under forward transport conditions was absent because the transporter spends most of the time in states in which the empty glutamate binding site faces the cytoplasm. These states are not anion conducting. In contrast, no transient current component, and only a small steady-state current (ISS = 10 pA) were observed for EAAC1H295K upon rapid application of 1 mM glutamate in the forward transport mode (Figure 2C). This behavior resembles that of the wild-type transporter in the absence of extracellular Na+ (17, 19), suggesting that Na+-dependent steps, such as translocation, are impaired. In agreement with this suggestion, EAAC1H295K under homoexchange conditions (140 mM NaSCN and 10 mM glutamate internal) shows a significantly slower time course than EAAC1WT for the current rise (19) with a time constant of 790 ± 200 ms (Figure 2C). The slow phase of the current rise under homoexchange conditions was previously assigned to the glutamate translocation reaction (19).

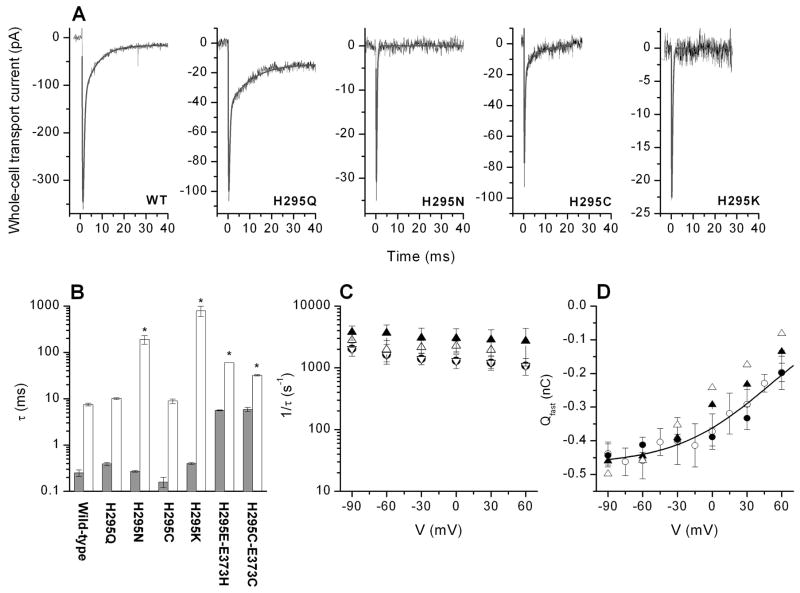

When measuring the pre-steady-state currents in the transport mode (in the absence of permeating anions), all of the mutant transporters studied exhibited inwardly-directed pre-steady-state currents upon applying a rapid concentration jump of extracellular glutamate generated by laser photolysis of MNI-caged glutamate (Figure 3A). The concentration of glutamate released from the caged precursor was estimated to be 60–90 μM. As demonstrated previously, EAACWT (Figure 3A) exhibits a very rapid rising phase of the electrogenic transport current in response to the glutamate concentration jump, followed by a decaying phase which consists of two components, a rapidly decaying component (τfast = 0.45 ± 0.04 ms (n = 7)) and a slowly decaying component (τslow = 7.5 ± 0.5 ms (n = 7)). Whereas both decaying phases of the pre-steady-state current were present in EAACH295Q (τfast = 0.39 ± 0.03 ms (n = 9), τslow = 10.1 ± 0.4 ms (n = 9)) and EAACH295C (τfast = 0.16 ± 0.04 ms (n = 8), τslow = 8.9 ± 1.0 ms (n = 8)), currents recorded from the other mutant transporters (EAACH295N and EAACH295K) were monophasic in their decaying behavior. The time constants for the single decaying phase for the latter two mutant transporters were τ = 0.27 ± 0.01 ms (H295N, n = 4) and τ = 0.40 ± 0.02 ms (H295K, n = 4). These time constants are similar to that of the fast decaying phase of wild-type EAAC1, suggesting that the rapidly decaying electrogenic component, which we had previously assigned to electrogenic Na+ binding to the glutamate-bound form of EAAC1 (20), is still present in these mutant transporters, whereas the slowly decaying component is missing. The slowly decaying component was previously attributed to electrogenic glutamate translocation across the membrane (17, 20). The time constants observed for the mutant transporters are summarized in Figure 3B.

Figure 3.

(A) Typical pre-steady-state transport currents recorded from wild-type and mutant transporters upon photolysis of 1 mM (WT, H295Q, H295C, H295N) or 4 mM (H295K) MNI glutamate at time 0. The transmembrane potential was 0 mV. The solid line represents the best fit with a sum of two exponentials (H295N and H295K), or three exponentials (WT, H295Q, H295C) to the data (see Materials and Methods). (B) Statistical analysis of the time constants for the rapidly decaying phase (grey bar) and slowly decaying phase (white bar) of the transport current. For the experiments indicated with a star the time constants were evaluated by analysis from the anion current, since the amplitude of the slow phase of the transport current was too small for those mutant transporters. (C) Voltage dependence of the time constants for the rapidly decaying phase (●: H295Q; △: H295C; ▽: H295N; ▲: H295K). (D) Voltage dependence of the charge moved during the rapidly decaying phase (Qfast). Qfast of the mutant transporters was normalized to the charge movement of the wild-type transporter to account for differences in expression levels. The symbols are the same as in (C). The open circles represent experiments from the wild-type transporter (20). The solid line is a fit of a Boltzmann-like equation with V1/2 = 54 mV and zapp = 0.55 (eq. 1, Materials and Methods section) to the wild-type data adapted from (20).

The rapidly decaying electrogenic current in the wild-type transporter shows a characteristic voltage dependence; only the total charge moved is voltage dependent, whereas the decay time constant is almost voltage independent. Qualitatively, this voltage dependence is conserved in EAAC1H295K, as well as in the charge neutralized transporters (Figure 3C and D), suggesting either that charge on the amino acid side chain in position 295 does not contribute to the fast glutamate induced charge movement, or that the lysine side chain in EAAC1H295K is not positively charged. To further test the protonation status of the mutant transporters we performed experiments as a function of extracellular pH.

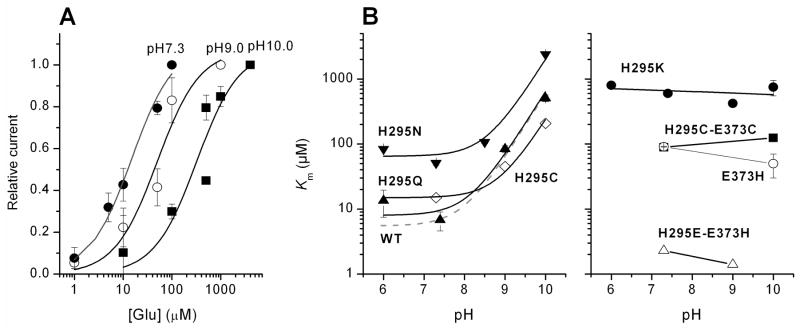

pH-dependence of Km

The dissociation constant of glutamate from the charge neutralized transporters was determined as a function of extracellular pH under homoexchange conditions. The data are summarized in Figure 4. EAAC1H295Q, EAAC1H295N and EAAC1H295C (Figure 4A) exhibit a steep increase of the Km for glutamate at pH values higher than 9. This increase in Km is very similar to that of the wild-type transporter (pK = 8.1 (6)) and occurs with comparable apparent pKa values (pK = 8.0 for EAAC1H295Q; pK = 8.9 for EAAC1H295N; pK = 9.0 for EAAC1H295C). In contrast, the Km of EAAC1H295K for glutamate is independent of the extracellular pH, even at pH values up to 10.0 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

(A) Glutamate dose response curves for EAAC1H295C anion currents at Vm = 0 mV and at extracellular pH values of 7.3, 9.0, and 10.0. Experiments were performed under homoexchange conditions (140 mM NaSCN and 10 mM glutamate internal). The solid lines represent best fits according to a Michaelis-Menten-like equation. (B) pH dependence of the apparent Km for glutamate for EAAC1H295C (diamonds), EAAC1H295Q (up triangle), EAAC1H295N (down triangle), EAAC1H295K (closed circles), EAAC1H295H (open circles), EAAC1H295C-E373C (squares), and EAAC1H295E-E373H (open triangle). The dotted line represents the pH dependence of the Km of EAAC1WT (20). The curved lines were calculated according to eq. (2) (Materials and Methods section). The apparent pKa values calculated for mutant transporters were: 8.0 (H295Q), 8.9 (H295N), and 9.0 (H295C).

Kinetics of H295-E373 double mutant transporters

The pH independence of EAAC1H295K shown in Figure 4B raises the possibility that the positively charged lysine side chain can substitute for the cotransported proton, thus generating a permanently protonated transporter. Since it was previously proposed that the cotransported proton associates with the glutamate residue in position 373 (8, 19), we tested the possibility that H295K and E373 form an ion pair. Thus, H295 and E373 may be physically close in space to allow ion pair formation. In order to establish a proximity relationship between these two residues, we generated H295-E373 double mutant transporters in procedures analogous to the ones used by the Kanner group (25) for glutamate transporter 1 (GLT-1), and determined their kinetic properties.

We first tested EAAC1 with the H295C-E373C double mutation. In a cysteine-less background this double mutation resulted in a non-functional transporter (data not shown). The function was not restored by incubation with 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) during cell culture and transfection, indicating that the two cysteines are not pre-oxidized. However, in the wild-type background, which contains five other cysteine residues, the function of EAAC1H295C-E373C was regained even in the absence of DTT. Average anion currents determined at saturating glutamate concentrations (1 mM) were −120 ± 49 pA (n = 8). Application of an oxidation reagent (100 μM Cu-phenanthroline) to EAAC1H295C-E373C in order to generate a disulfide linkage between these two residues had very little effect on glutamate-induced anion currents (I/I0 = 0.82 ± 0.1, n = 4). Furthermore, incubation with 1 mM DTT, in order to reduce a possible pre-existing disulfide linkage, was ineffective (I/I0 = 0.9 ± 0.1, n = 3). Finally, application of 100 μM Cd2+, which is known to be complexed by two cysteine residues close in space (26), did not alter glutamate induced anion currents in EAAC1H295C-E373C (I/I0 = 0.88 ± 0.19, n = 8). Together, these results suggest that H295C and E373C are not close enough in space to from a disulfide linkage.

Second, we tested the EAAC1H295E-E373H transporter, which contains two charge reversal mutations. EAAC1H295E-E373H was functional in the homoexchange mode (average anion current = −530 ± 20 pA). However, no currents could be observed in the forward transport mode either in the presence or absence (Fig. 1D and Fig. 2C) of permeating anions (intracellular SCN−). Is EAAC1H295E-E373H functional because of the charge reversal of a possible ion pair between H295 and E373? In order to answer this question we generated a E373H mutant transporter which would be expected to be non-functional if H295 and E373 would form an ion pair. In contrast to this expectation, EAAC1E373H catalyzed anion currents in the homoexchange mode (average anion current = −286 ± 179 pA, n = 6) upon application of 1 mM glutamate (data not shown). These anion currents saturated with a Km of 91 ± 1 μM (n = 3) at an extracellular pH of 7.3. Raising the pH to 10.0 resulted in a Km of 50 μM ± 20 μM (n = 3, Figure 4B), showing that the glutamate affinity of EAAC1E373H is independent of the extracellular pH.

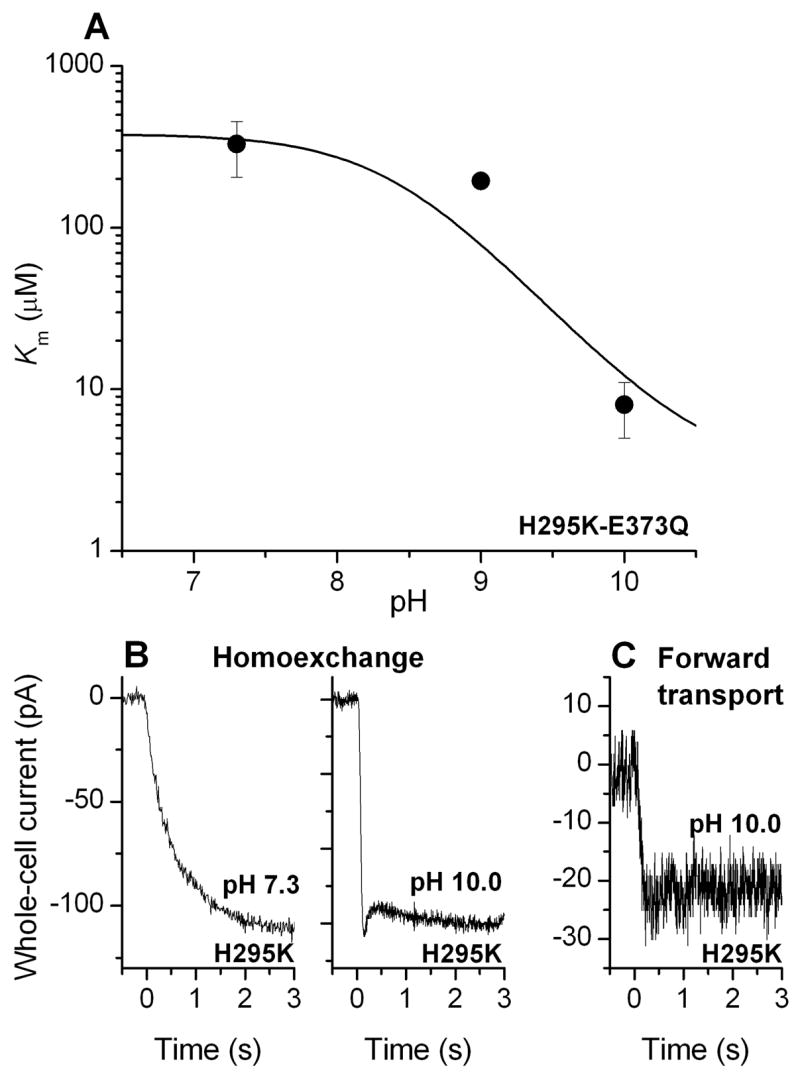

pH dependence of EAAC1H295K-E373Q

The results obtained from the double mutants suggest that H295 and E373 are not close in space, excluding the possibility that a protonated H295K substitutes for the cotransported proton. A second possibility would be that glutamate transport by EAAC1H295K is pH independent because deprotonation of the lysine side chain counterbalances the simultaneously occurring deprotonation of E373, thus leading to virtual pH independence of the Km for glutamate. We tested this hypothesis by generating the H295K mutation in the background of the E373Q mutation, which was proposed to generate a transporter that is permanently protonated at the site of the cotransported proton (6), thus eliminating the intrinsic pH-dependence of EAAC1 transport. The pH dependence of the Km of EAAC1H295K-E373Q for glutamate is shown in Figure 5A. Whereas the Km was almost independent of the extracellular pH between pH 7.3 and 9.0, it decreased steeply when the pH was raised to 10.0 (Km = 6.2 ± 1.4 μM), almost restoring the Km to values found for the E373Q mutant transporter (Km = 10 ± 5 μM). Furthermore, the dramatic slowing of the rise of the anion current in the homoexchange mode of EAAC1H295K (Figure 5B, left panel) was reverted when the extracellular pH was raised from 7.3 to 10.0 (Figure 5B, right panel). Together, these results indicate that deprotonation of H295K restores the functionality of the transporter with regard to glutamate affinity and translocation kinetics. To further test this hypothesis, we performed additional experiments with EAAC1H295K at pH 10.0. If the hypothesis is correct, we would expect that forward transport activity of EAAC1H295K should be restored at pH 10. As shown in Figure 5C, glutamate induced steady-state anion current in EAAC1H295K in the forward transport mode at pH 10.0 (29 ± 7 pA, n = 8), but only when the intracellular pH was raised to 10 at the same time. At an intracellular pH of 7.4 no forward transport activity was observed (data not shown). This result suggests that the lysine side chain becomes protonated from the intracellular side at a cytosolic pH of 7.4, thus preventing forward transport by inhibiting the K+-induced relocation of the empty transporter.

Figure 5.

(A) pH dependence of the apparent Km of EAAC1H295K-E373Q for glutamate. The intracellular solution contained 140 mM NaSCN and 10 mM glutamate (homoexchange conditions). The solid line represents a simulation according to eq. (3) (Materials and Methods section) with a pKa of 10.5. (B) Typical current recordings from EAAC1H295K -expressing cells after application of 1 mM glutamate at t = 0 at an extracellular pH of 7.3 (left panel) and 10.0 (right panel). The data are from two different cells. The transmembrane potential was 0 mV. The intracellular solution contained 140 mM NaSCN and 10 mM glutamate (homoexchange conditions). (C) Typical current recording from a EAAC1H295K -expressing cell after application of 5 mM glutamate at t = 0 at an extracellular pH of 10.0 (forward transport conditions, 140 mM cytosolic KSCN). The intracellular pH was 10.0.

Discussion

Conserved histidine residues are involved in the transmembrane transport of protons in a number of transport systems, such as the lac-permease from E. coli (11, 12), the Na+/H+- antiporter (14), and the peptide transporters (15). Here, we show that the conserved histidine 295 in the 6th putative transmembrane domain of the glutamate transporters is not responsible for proton cotransport by EAAC1. This finding is based on the fact that after substitution of histidine 295 with glutamine substrate binding by the mutant EAAC1 is still affected by the extracellular pH. Thus, it appears that the intrinsic protonation site of EAAC1, which is responsible for H+ cotransport, can still be protonated, even in the absence of an amino acid residue with ionizable side chain in position 295. In addition, the kinetics of substrate translocation and transport by EAAC1H295Q, as well as their voltage dependence, were similar to those of the wild-type transporter, indicating that the side chain of histidine 295, although its protonation state is functionally significant, does not carry charge in EAAC1 at physiological pH. Thus, H295 does not contribute to glutamate-induced transmembrane charge movement. In contrast, when H295 was replaced by lysine, an amino acid residue with a more easily protonatable side chain compared to histidine (the pKa of lysine in small model peptides is 10.4 (27)), the resulting mutant transporter was defective in partial reactions other than Na+ binding, suggesting that introduction of a positive charge in position 295 strongly interferes with transport. In the H295K mutant transporter the functional effects of protonation at the introduced lysine residue by pH titration are masked by the simultaneous deprotonation of the intrinsic proton acceptor of EAAC1, E373. Therefore, to directly determine the protonation status of H295K, we eliminated intrinsic protonation of E373 by generating the H295K-E373Q double mutant transporter. The results from the experiments with the double mutant transporter suggest that protonation at H295 has a modulatory role for EAAC1 function. When the positive charge at the lysine side chain in position 295 was removed by pH titration, the glutamate binding affinity of the double mutant transporter was restored to close to wild-type levels, indicating that the charge and not the increased length of the lysine side chain results in the dramatic decrease in glutamate affinity. This result supports the hypothesis that in the wild type transporter H295 does not carry charge.

Our data suggest that, in addition to the charge, the amino acid side chain volume and/or length play an important role in position 295. It is well known that the −CONH2 group of glutamine can substitute for the NH(ε) of the histidine ring, whereas the −CONH2 of asparagine can substitute for the NH(δ) (27). Since the function of EAAC1H295Q is unimpaired compared to the wild-type, but function of H295N is impaired, we can speculate that the histidine NH(ε) acts as a hydrogen bond donor to some other unidentified acceptor and that this hydrogen bonding interaction is crucial for glutamate translocation, as well as for the K+-induced relocation reaction of EAAC1. Interestingly, the lysine side chain may also be able to substitute for histidine, but only in its deprotonated, neutral form. For side chains with lower volume, such as asparagine and cysteine, the main effect is to slow down K+-induced relocation, although glutamate translocation in EAAC1H295N is also significantly slower than in the wild-type transporter.

Our results agree well with previous observations reported by the Kanner group (28). These authors showed that the function of the glutamate transporter subtype GLT-1 with neutral side chains in position 326 (analogous to H295 in EAAC1) could not be restored by generating double mutant transporters with additional charge neutralization mutations of D367, E373 and D439 (all EAAC1 numbering). Because H295 is not charged, it is unlikely to be involved in electrostatic interactions that are necessary for salt bridge formation. Furthermore, it appears that the side chains of E373 and H295 are physically apart from each other, as demonstrated by our inability to modify the E373C-H295C double mutant transporter with oxidizing or reducing agents. Together, these results exclude a model in which E373 and H295 interact to form a salt bridge or a proton binding network. However, our results differ from those published earlier on H295 mutant transporters in that it had been proposed that histidine can not be replaced with any other amino acid, either basic or neutral, without loss of function (16). Here, we show that amino acids with neutral side chains in position 295 either support the full transport cycle (H295Q), or at least glutamate translocation (H295N and H295C). Therefore, our work provides another example that it is important to determine the effect of site-specific mutations on partial reactions of the transporters.

The protonation status of the amino acid side chain in position 295 has a strong effect on the apparent affinity of EAAC1 for glutamate and on the rate of glutamate translocation. Positive charge on the side chain of the lysine substitution inhibits glutamate binding to EAAC1, shifting its apparent Km to higher values by about two orders of magnitude, as shown by pH titration of the H295K-E373Q double mutant transporter (Figure 5A). Could this decrease in apparent affinity be caused by the slowed glutamate translocation reaction, such that the intrinsic Km for glutamate is measured for EAAC1H295K, whereas the apparent Km is determined for EAAC1WT? The intrinsic dissociation constant of glutamate from wild-type EAAC1 was estimated to be 50 μM, about 10-times the apparent Km determined under steady-state conditions. Even if our measurements reported here would determine the intrinsic Km of EAAC1H295K, it would still be 10-times higher than the intrinsic Km of the EAAC1WT. Therefore, we propose that the increase in apparent Km observed for EAAC1H295K is caused by a real change in glutamate binding kinetics, and not by changes to the rates of other partial reactions that follow glutamate binding. Although an indirect, long-range effect on glutamate binding can not be fully excluded, we speculate that a positive charge in position 295 interacts electrostatically either with the positively charged amino group of the substrate glutamate, or with the guanidinium group of R446, which is conserved in the glutamate binding site and associates with the γ-carboxylate of the bound glutamate (29). In both scenarios glutamate binding would be inhibited by electrostatic repulsion of two positive charges: One on H295K and the other either on glutamate, or on an amino acid in the substrate binding site.

The general mechanism that we propose for modulation of glutamate transporter function by protonation in position 295 is shown in Figure 6A. The model distinguishes between two protons: The cotransported H+, which associates with E373, and a modulatory H+, which associates with the amino acid side chain in position 295. Association of the cotransported proton with E373 is shown on the horizontal axis. Binding of this proton increases the affinity of EAAC1WT for glutamate, such that the Km is about 6 μM when E373 is fully protonated at physiological pH, and Km increases steeply when E373 becomes deprotonated at more basic extracellular pH (Figure 6B). In contrast, association of the modulatory proton with position 295, as shown on the vertical axis in Figure 6A, leads to a dramatic decrease in the affinity of the transporter for glutamate. Once the residue in position 295 becomes deprotonated at basic pH values, the glutamate affinity returns to a value similar to EAAC1WT at neutral pH. According to this model, the Km for glutamate of the H295K mutant transporter is virtually independent of the external pH because the effects of dissociation of the cotransported and the modulatory protons cancel each other out (Figure 6B). However, after eliminating dissociation of the cotransported H+ by generating the double mutant transporter EAAC1H295K-E373Q, only the modulatory proton can bind. Thus, the model predicts that the Km for glutamate decreases with increasing pH for this double-mutant transporter (Figure 6B), in agreement with the experimental data shown in Figure 5. The effect of proton modulation in position 295 is only observed when the histidine residue is replaced by lysine, which is much more easily protonated. For the wild-type transporter, the model predicts that the modulatory site is never occupied by a proton in the pH range that is experimentally accessible, suggesting that the pKa of H295 is in the range of 5.0 or lower. In addition to its effect on the Km for glutamate, binding of the modulatory proton also decreases the rate for glutamate translocation by a factor of 100, as illustrated in Figure 6A.

The model shown in Figure 6A does not include Na+ binding steps, since binding of the modulatory proton appears to have no effect on at least the Na+ binding reactions which follow glutamate binding. Glutamate-induced Na+ binding to the transporter is associated with inward movement of positive charge (30). The rate of this charge movement, as well as its voltage dependence are not significantly changed in the H295K mutant transporter. Therefore, the additional charge on the protonated lysine residue does not contribute to this charge movement, indicating that the lysine side chain does not move during the Na+ binding reaction, or that it moves without sensing the electric field of the membrane. In contrast, transient current previously assigned to the glutamate translocation reaction is inhibited in EAAC1H295K. Inhibition of this transient current is observed because the rate constant associated with glutamate translocation is slowed by a factor of 100 in the EAAC1H295K transporter compared to the wild-type. Thus, if the same charge is moved, the maximum amplitude of the transient current would also be reduced 100-fold, making it too small to be observed in our experiments. The simplest interpretation of these results would be that the protonated lysine in the H295K transporter slows glutamate translocation because this part of the transporter moves within the membrane during the conformational change that accompanies translocation. Positive charge would inhibit this movement because the probability of its partitioning into the membrane is low.

While this manuscript was under review, a three-dimensional structural model of a bacterial glutamate transporter homologue GltP from Pyrococcus Horikoshii was published (31). This structural model mainly corroborates the findings of our work presented here. The distance between the positions homologous to E373 and H295 in GltP is 13.5 Å, making it unlikely that the cysteines introduced into these positions can be covalently linked by oxidation. Furthermore, both positions are localized in the hydrophobic interior of the transporter, thus explaining their unusual pKa values. Q318, which is homologous to E373 in EAAC1 is protected from the water phase by the first hairpin loop between transmembrane helices 6 and 7. This protection from direct accessibility from the aqueous medium may be responsible for the stabilization of the protonated form of E373 (pKa = 8). Our speculation that H295 is localized close to the glutamate binding site is, however, not supported by the crystal structure (31). H295 is separated by transmembrane helices 7 and 8 from the putative glutamate binding site and, thus, not close enough to interact directly through an electrostatic mechanism with residues involved in glutamate binding, such as R446. Although a long-range effect may be possible, we offer the following alternative explanation for the effect of the mutation on glutamate binding: The structural model indicates that H295 may be close in space to D367. Although the two homologous residues in the bacterial transporter, D312 and Q342, are too far apart for direct ion pair formation (approximately 5 Å), substitution of H295 with the longer lysine side chain might bring the two charged groups closer together. Since D367 is located in a hydrophilic pocket which is buried deep in the transmembrane region of the transporter and which is physically removed from the glutamate binding site, it is conceivable that this hydrophilic pocket may form the binding site for the Na+ ion that binds to the empty transporter in the absence of glutamate. Thus, protonation of K295 could inhibit glutamate binding and translocation by inhibiting binding of this “first” sodium ion to EAAC1. It is well known that binding of this Na+ ion is necessary to generate a high-affinity binding site for glutamate on the transporter (20). Binding of further Na+ ion(s) to the glutamate-bound form of EAAC1 most likely takes place closer to the glutamate binding site, but far away from H295. Therefore, mutations in position 295 do not affect sodium binding to the substrate-loaded transporter.

In conclusion, this work has provided evidence that the conserved histidine residue in position 295 of EAAC1 is not protonated at physiological pH. Thus, it does not contribute to proton cotransport by EAAC1. However, positive charge introduced into position 295 by a histidine-to-lysine substitution modulates the affinity of EAAC1 for glutamate and the rate of glutamate translocation.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to D. Landowne for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful comments and suggestions.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01-NS0493 and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants GR 1393/2-2,3 to CG.

Abbreviations

- EAAC1

Excitatory amino acid carrier 1

- GLT-1

Glutamate transporter 1

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- HEPES

4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- TEA

Tetraethyl ammonium

- TMR

Tetramethylrhodamine

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis-(beta-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetracetic acid

- MNI glutamate

4-methoxy-7-nitroindolinyl caged glutamate

- HEK

Human embryonic kidney

- TM

Transmembrane domain

- DTT

Dithiothreitol

References

- 1.Kanner BI, Sharon I. Active transport of L-glutamate by membrane vesicles isolated from rat brain. Biochemistry. 1978;17:3949–3953. doi: 10.1021/bi00612a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanner BI, Bendahan A. Binding order of substrates to the sodium and potassium ion coupled L-glutamic acid transporter from rat brain. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6327–30. doi: 10.1021/bi00267a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erecinska M, Wantorsky D, Wilson DF. Aspartate transport in synaptosomes from rat brain. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:9069–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zerangue N, Kavanaugh MP. Interaction of L-cysteine with a human excitatory amino acid transporter. J Physiol. 1996;493:419–23. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zerangue N, Kavanaugh MP. Flux coupling in a neuronal glutamate transporter. Nature. 1996;383:634–637. doi: 10.1038/383634a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watzke N, Rauen T, Bamberg E, Grewer C. On the mechanism of proton transport by the neuronal excitatory amino acid carrier 1. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:609–22. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.5.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seal RP, Shigeri Y, Eliasof S, Leighton BH, Amara SG. Sulfhydryl modification of V449C in the glutamate transporter EAAT1 abolishes substrate transport but not the substrate-gated anion conductance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:15324–15329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011400198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grewer C, Watzke N, Rauen T, Bicho A. Is the Glutamate Residue Glu-373 the Proton Acceptor of the Excitatory Amino Acid Carrier 1? J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2585–2592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207956200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Utsunomiya-Tate N, Endou H, Kanai Y. Cloning and functional characterization of a system ASC-like Na+-dependent neutral amino acid transporter. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14883–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broer A, Brookes N, Ganapathy V, Dimmer KS, Wagner CA, Lang F, Broer S. The astroglial ASCT2 amino acid transporter as a mediator of glutamine efflux. J Neurochem. 1999;73:2184–2194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padan E, Sarkar HK, Viitanen PV, Poonian MS, Kaback HR. Site-specific mutagenesis of histidine residues in the lac permease of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6765–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.20.6765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abramson J, Smirnova I, Kasho V, Verner G, Kaback HR, Iwata S. Structure and Mechanism of the Lactose Permease of Escherichia coli. Science. 2003;301:610–615. doi: 10.1126/science.1088196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiebe CA, Dibattista ER, Fliegel L. Functional role of polar amino acid residues in Na+/H+ exchangers. Biochem J. 2001;357:1–10. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiebe CA, Rieder C, Young PG, Dibrov P, Fliegel L. Functional analysis of amino acids of the Na+/H+ exchanger that are important for proton translocation. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;254:117–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1027311916247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen XZ, Steel A, Hediger MA. Functional Roles of Histidine and Tyrosine Residues in the H+-Peptide Transporter PepT1. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2000;272:726–730. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Pines G, Kanner BI. Histidine 326 is critical for the function of GLT-1, a (Na+ + K+)-coupled glutamate transporter from rat brain. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19573–19577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grewer C, Watzke N, Wiessner M, Rauen T. Glutamate translocation of the neuronal glutamate transporter EAAC1 occurs within milliseconds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9706–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160170397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen C, Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2745–52. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wadiche JI, Amara SG, Kavanaugh MP. Ion fluxes associated with excitatory amino acid transport. Neuron. 1995;15:721–728. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watzke N, Bamberg E, Grewer C. Early intermediates in the transport cycle of the neuronal excitatory amino acid carrier EAAC1. J Gen Physiol. 2001;117:547–62. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.6.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergles DE, Tzingounis AV, Jahr CE. Comparison of Coupled and Uncoupled Currents during Glutamate Uptake by GLT-1 Transporters. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10153–10162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10153.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canepari M, Nelson L, Papageorgiou G, Corrie JET, Ogden D. Photochemical and pharmacological evaluation of 7-nitroindolinyl-and 4-methoxy-7-nitroindolinyl-amino acids as novel, fast caged neurotransmitters. J Neurosci Meth. 2001;112:29–42. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan RM, Vandenberg RJ. Distinct Conformational States Mediate the Transport and Anion Channel Properties of the Glutamate Transporter EAAT-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13494–13500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109970200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wadiche JI, Kavanaugh MP. Macroscopic and microscopic properties of a cloned glutamate transporter/chloride channel. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7650–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07650.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brocke L, Bendahan A, Grunewald M, Kanner BI. Proximity of Two Oppositely Oriented Reentrant Loops in the Glutamate Transporter GLT-1 Identified by Paired Cysteine Mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3985–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107735200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glusker JP. Structural aspects of metal liganding to functional groups in proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 1991;42:1–76. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60534-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fersht A. Structure and mechanism in protein science. W. H. Freeman and Company; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pines G, Zhang Y, Kanner BI. Glutamate 404 is involved in the substrate discrimination of GLT-1, a (Na+ + K+)-coupled glutamate transporter from rat brain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17093–17097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bendahan A, Armon A, Madani N, Kavanaugh MP, Kanner BI. Arginine 447 Plays a Pivotal Role in Substrate Interactions in a Neuronal Glutamate Transporter. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37436–37442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wadiche JI, Arriza JL, Amara SG, Kavanaugh MP. Kinetics of a human glutamate transporter. Neuron. 1995;14:1019–1027. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yernool D, Boudker O, Jin Y, Gouaux E. Structure of a glutamate transporter homologue from pyrococcus horikoshii. Nature. 2004;431:811–818. doi: 10.1038/nature03018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grunewald M, Bendahan A, Kanner BI. Biotinylation of single cysteine mutants of the glutamate transporter GLT-1 from rat brain reveals its unusual topology. Neuron. 1998;21:623–32. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80572-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]