Abstract

The combination of cisplatin and ionizing radiation treatment represents a common modality for treating a variety of cancers. These two agents provide considerable synergy during treatment although the mechanism of this synergy remains largely undefined. We have investigated the mechanism of cisplatin sensitization to IR using a combination of in vitro and in vivo experiments. A clear synergistic interaction between cisplatin and ionizing radiation (IR) is observed in cells proficient in non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) catalyzed repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSB). In contrast, no interaction between cisplatin and IR is observed in NHEJ deficient cells. Reconstituted in vitro NHEJ assays revealed that a site-specific cisplatin-DNA lesion near the terminus results in complete abrogation of NHEJ catalyzed repair of the DSB. These data demonstrate that the cisplatin-IR synergistic interaction requires the DNA-PK dependent NHEJ pathway for joining of DNA DSBs, and the presence of a cisplatin lesion on the DNA blocks this pathway. In the absence of a functional NHEJ pathway, while the cells are hypersensitive to IR, there is no synergistic interaction with cisplatin.

Introduction

The role of the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway in repairing ionizing radiation (IR) induced DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) is well established 1. However, the mechanism by which the NHEJ pathway responds to compound DNA lesions, including those induced by cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (II) (cisplatin), is less well defined. Cisplatin is a chemotherapeutic drug used in conjunction with IR to treat various types of cancer, including cervical carcinoma as well as head and neck cancers 2,3. While the mechanism of cisplatin sensitization to IR remains largely undefined, evidence suggests that the NHEJ pathway is involved 4,5

The chemotherapeutic efficacy of cisplatin is afforded by the ability to form covalent DNA adducts including intrastrand 1,2d (GpG) and 1,3d (GpXpG) adducts and interstrand G-G cross-links. These adducts distort the DNA structure thereby inhibiting replication and transcription, and if not repaired, lead to cell death via the apoptotic pathway 6–8. Repair of cisplatin-DNA intrastrand lesions is largely catalyzed by the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway 9–11. The molecular mechanism of cisplatin-interstrand crosslink repair has not been elucidated, and even less is known about pathways required for the repair of compound lesions such as those generated by IR treatment of cisplatin damaged DNA.

Exposure to IR induces single-strand and double-strand DNA breaks as well as various types of nucleobase damage 12. Repair of IR induced DNA DSBs is catalyzed predominantly by the NHEJ pathway, however, the homologous recombination pathway has also been implicated in their repair 13–16. Repair of DNA DSBs via the NHEJ pathway requires the concerted action of a series of protein complexes. The DNA end-binding complex DNA-PK consists of the Ku heterodimer, which facilitates binding of the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PKcs) 17,18. The crystal structure of the Ku heterodimer complexed with a double-stranded DNA terminus has been solved and reveals a unique organization where a base, two pillars and a bridge form a tunnel through which a duplex DNA can thread 19. In order to observe maximal kinase activity, the Ku subunits are first threaded onto the DNA substrate 20. The Ku dimer then slides inward on the DNA by a single helical turn in an ATP independent reaction. This structure then results in the association of DNA-PKcs with Ku and the DNA termini 20–22. We have determined that Ku translocation on duplex DNA is significantly inhibited by the presence of cisplatin-DNA lesions, and that DNA-PK activity is inhibited by the presence of cisplatin on the DNA termini 23. Following the association of DNA-PKcs, processing of the termini is likely to be required. Another protein, artemis, has also been demonstrated to form a complex with and serve as a substrate for phosphorylation by DNA-PKcs 24. Artemis has an associated 5′-3′ exonuclease activity, and following phosphorylation by DNA-PKcs, acquires a single-stranded flap like endonuclease activity 24 similar to the endonuclease activity of the Fen-1 class of enzymes 25,26. The Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 complex (MRN) is also required for NHEJ catalyzed double-strand break repair and may also play an important role in processing the DNA termini 27–29. The MRN complex exhibits ATPase, DNA binding and DNA strand annealing activity in addition to a single-stranded exonuclease activity all of which are potentially involved in processing DNA termini 29,30. The processing events may facilitate the search for regions of microhomology near the termini or simply generate blunt DNA ends which can then be ligated. In vitro analyses demonstrate that blunt ended DNA fragments can be joined by the NHEJ pathway although the efficiency of the reaction is increased if the DNA contains cohesive ends31. Following processing of the DNA termini, the formation of the phosphodiester bonds completes joining of the DSB and is catalyzed by the DNA ligase IV/XRCC4 complex 30,32,33. In addition, the XRCC4 subunit is a substrate for DNA-PKcs phosphorylation, although mutational analysis revealed that phosphorylation of XRCC4 is not required for NHEJ 34.

To further investigate the role of NHEJ in cisplatin sensitization to IR, we have employed a series of cell lines that are either wild type or devoid of DNA-PK 35 and determined the interaction between cisplatin and IR. We have selected median effect analysis as the method to determine the dose-effect relationship between cisplatin and IR treatment 36. Median effect analysis has been used extensively to determine the interaction of two drugs in combined treatment regimens 37–39. This analysis has also been employed specifically to analyze the importance of dosing schedule in cisplatin and IR combined treatment 40. By employing a reconstituted in vitro assay using modified synthetic DNA substrates, we demonstrate that a single cisplatin-DNA lesion near a DSB is sufficient to completely block rejoining of the DNA termini via NHEJ. These results demonstrate that the molecular mechanism of cisplatin sensitization of cells to IR involves inhibition DNA-PK catalyzed phosphorylation of target proteins and ultimately inhibition of NHEJ catalyzed DNA end joining.

Results

NHEJ status influences cisplatin radiosensitization

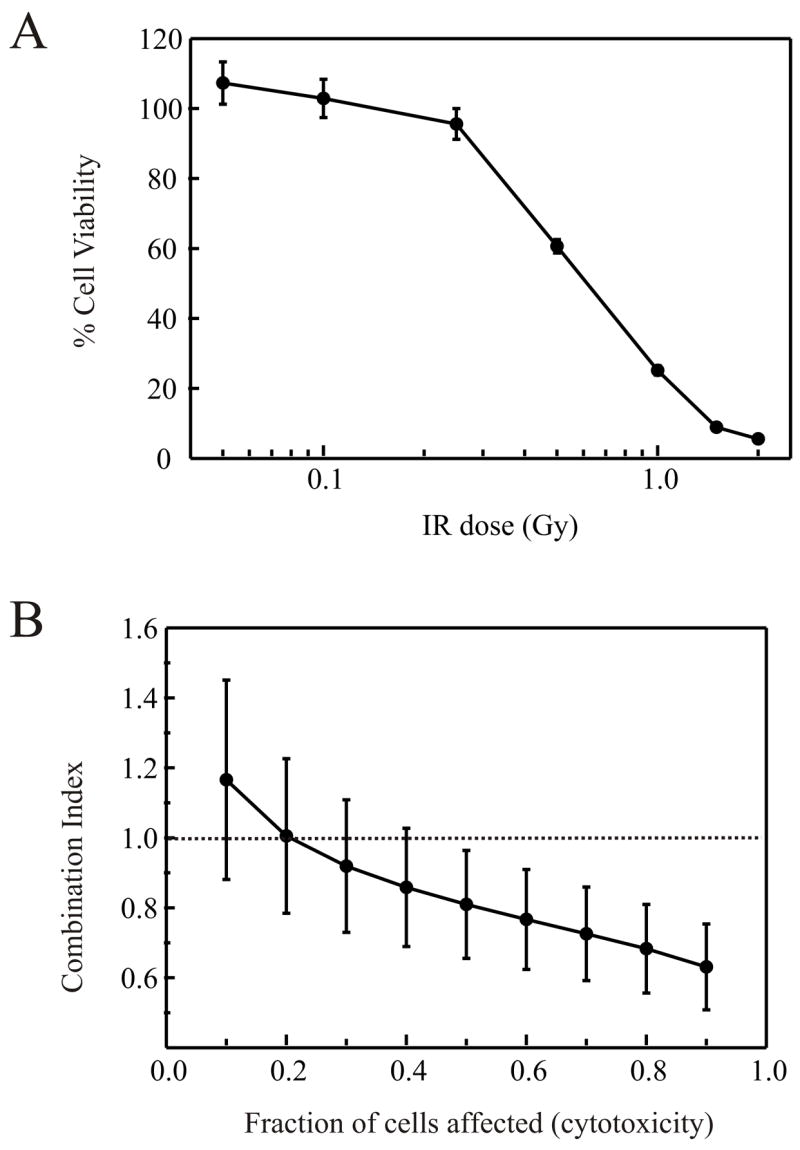

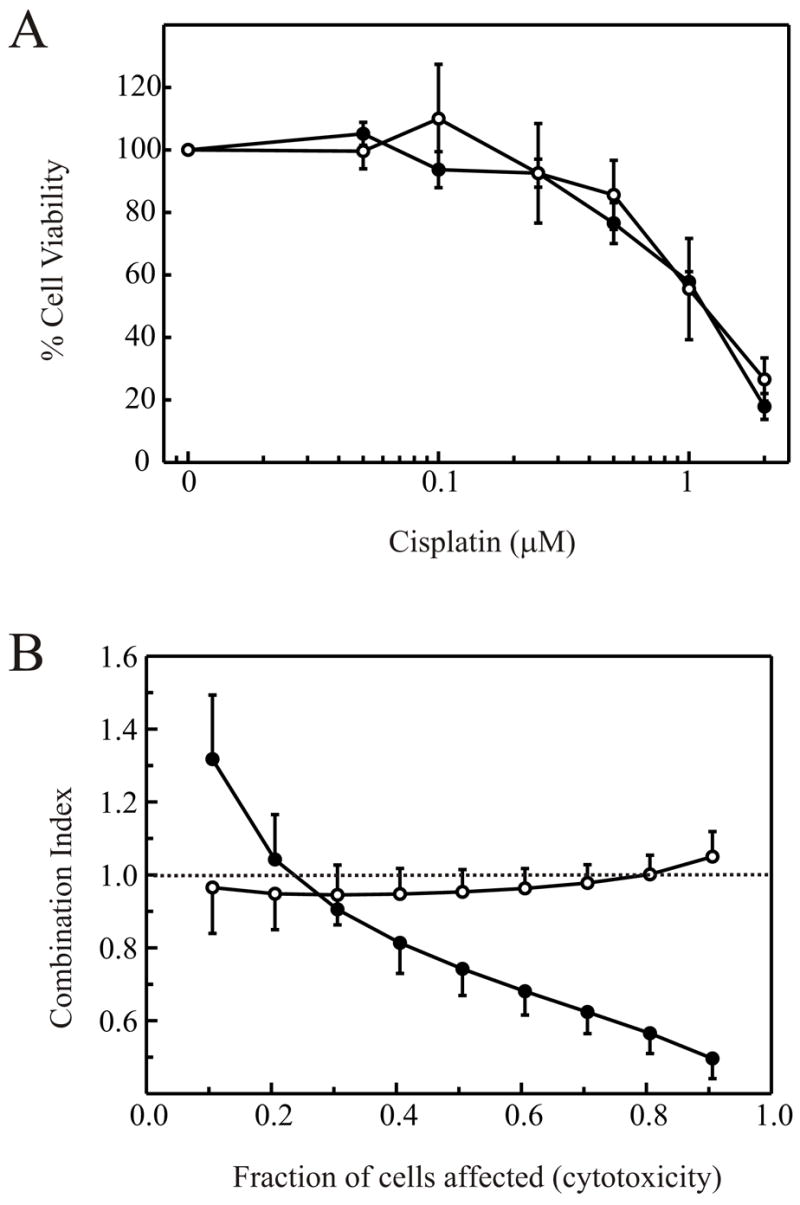

In an effort to elucidate the molecular mechanism by which cisplatin and IR synergize to afford greater cytotoxicity than either agent individually, we undertook analyzing the cisplatin-IR interaction in a series of cell lines differing in their ability to catalyze DSB repair via NHEJ. We employed median effect analysis, which allows potential interactions, both antagonistic and synergistic, to be quantitatively studied over the complete range of cells affected by the combined treatment. We have measured the end point of colony forming ability following treatment and therefore the fraction of cells affected is analogous to the degree of cytotoxicity. Procedurally, median effect analysis involves determination of LD50 values for the individual agents and then treatment of the cells with increasing doses of the agents together while maintaining a constant ratio of each agent based on the LD50 36. The combination index (CI) is then calculated over a range of cells affected which allow the measured effect of the combined treatment to be compared to the expected result if the two agents act in a simply additive fashion. A CI equal to 1 indicates no interaction while a CI less than 1 indicates synergy. Antagonistic interactions are indicated by a CI value greater than 1. To validate this methodology and provide a base line of synergism, we employed the ovarian epithelial cancer cell line A2780 which displays wild-type levels of DNA-PK 7 and are sensitized to IR by cisplatin 41,42. Analysis of A2780 cell sensitivity to cisplatin revealed a toxicity curve similar to that previously published 8 and an LD50 of 3.0μM was calculated (data not shown). The IR toxicity curve of A2780 cells is presented in Figure 1A and revealed a LD50 of approximately 0.5 Gy. The combined treatment protocol consisted of a 4 hour pre-treatment with cisplatin. The cisplatin containing media was removed, replaced with PBS in the absence of cisplatin, and the cells were immediately treated with the indicated doses of IR. Following these treatments, fresh media was added and the clonogenic colony forming survival assay was performed as described in “Materials and Methods”. The CI was calculated and plotted versus fraction of cells affected (Figure 1B). The results revealed that at the lower fraction of cells affected, IR and cisplatin were antagonistic, indicated by CI values greater than 1. As the fraction of cells affected increased, a transition through an additive interaction into synergism was observed as evidenced by the CI values decreasing below a value of 1. These results demonstrate that the interaction of cisplatin and IR was clearly dependent on the total dose, and differed as the fraction of cells affected increased. The treatment with low levels of cisplatin was antagonistic to IR and may be the result of a checkpoint response which enhances repair of the DNA double strand breaks induced by IR treatment. Having validated the median effect analysis in A2780 cells, we further examined the effect of cisplatin and IR in a pair of human glioma cell lines. The MO59J cells are devoid of DNA-PK, deficient in NHEJ, and therefore hypersensitive to IR. A second cell line, MO59K, is established from the same cancer, displays near wild-type levels of DNA-PK, is competent for NHEJ and does not display hypersensitivity to IR 35. Clonogenic colony forming assays were performed on these two cell lines and were consistent with the published values for IR sensitivity, with the MO59K and MO59J line exhibiting LD50 values of 0.5 Gy and 0.1 Gy respectively (data not shown). The results presented in Figure 2A reveal a nearly identical LD50 for cisplatin in each cell line (1.3μM). Median effect analysis was then performed and the results are presented in Figure 2B. The results obtained from the DNA-PK positive MO59K cells (filled circles) revealed a curve that was similar to that observed for the A2780 cells, with an antagonistic interaction observed at the lower percentages of cells affected and clear synergism at higher percentages of cells affected. The results observed for the DNA-PK null MO59J cells (open circles) are significantly different with the CI remaining very close to a value of 1 over the entire range of cells affected. No synergism was observed even at the highest fraction of cells affected. These data demonstrate that in DNA-PK null cells there was no antagonistic or synergistic interaction between cisplatin and IR, thus the synergism between these two agents requires DNA-PK and a functional NHEJ pathway to repair the IR-induced DNA DSBs.

Figure 1.

Cisplatin and IR synergy in DNA-PK positive A2780 ovarian carcinoma cells. A: Cells were treated with varying doses of ionizing radiation and plated into colony forming assays. Cell viability was determined by expressing the number of colonies as a percentage of the number of colonies present in mock treated control plates and was plotted versus IR dose. B: Combined cisplatin and IR treatment was performed as described in “Materials and Methods”. Combination indices were calculated from at least three separate experiments and averages and standard errors plotted versus fraction of cells affected.

Figure 2.

Interaction of cisplatin and IR is dependent on DNA-PK status. A: Cells were treated with the indicated concentration of cisplatin for 4 hours and were plated into colony forming assays as described in “Materials and Methods”. Cell viability was determined by expressing the number of colonies as a percentage of the number of colonies present in mock treated control plates and plotted versus cisplatin dose. MO59K cells are depicted with filled circles while MO59J cells are depicted with open circles. B: Combined cisplatin and IR treatment was performed as described in “Materials and Methods”. Combination indices were calculated from at least three separate experiments and averages and standard errors plotted versus fraction of cells affected.

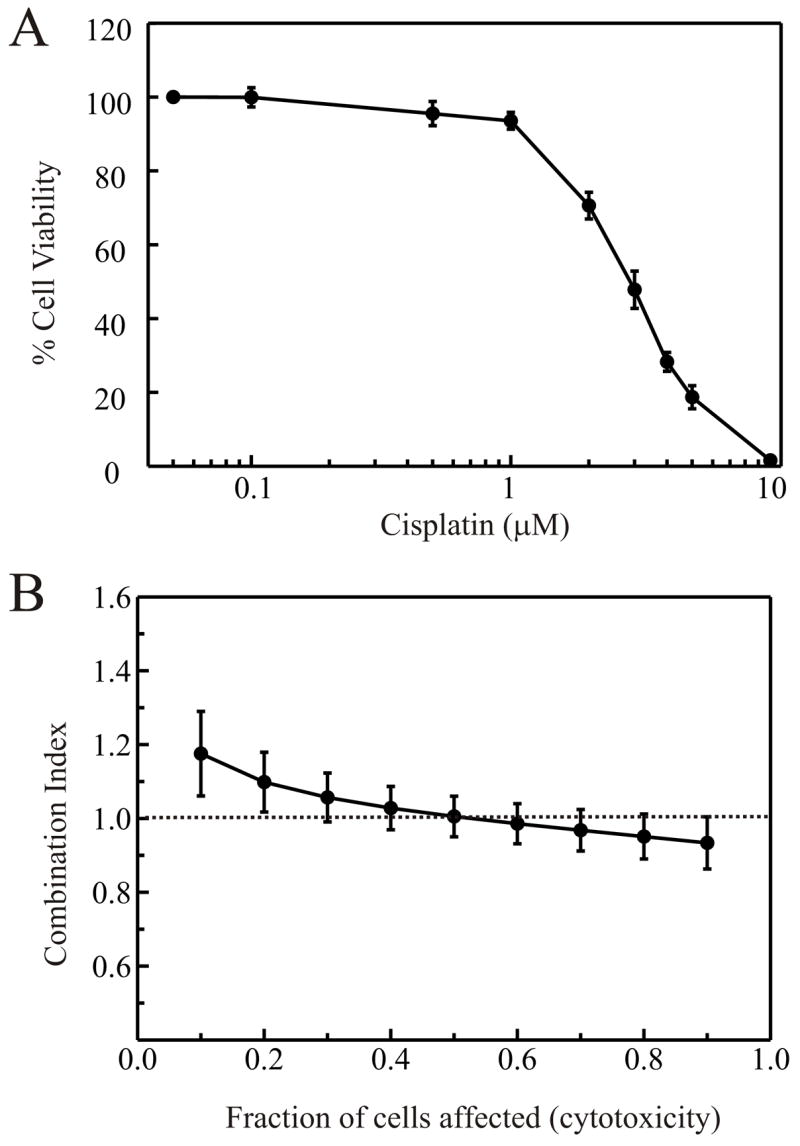

MO59J cells that are devoid of DNA-PK also exhibit reduced expression of the Ataxia telengeictasia mutated (ATM) protein 43. While the importance of ATM in signaling the DNA damage response to IR is well established 44,45, the levels of ATM do not correlate with radiosensitivity 43. If the synergism between IR and cisplatin involves DNA-PK and NHEJ, the inability to signal to this pathway may also be expected to reduce synergism. Therefore, we employed the ATBiva cell line which is devoid of ATM, and analyzed the interaction between cisplatin and IR. The cisplatin toxicity curve revealed a LD50 value of 2.5 μM for the ATBiva cells (Figure 3A). The LD50 for IR in ATBiva cells was found to be 0.3 Gy, consistent with published data (data not shown). Median effect analysis revealed that the lack of ATM also resulted in a reduction in the ability of IR and cisplatin to synergize (Figure 3B). Since ATM lies upstream of DNA-PK, the inability to signal to the NHEJ pathway and induce cell cycle arrest in response to IR suggests that activation of NHEJ is also required for the synergistic activity of IR and cisplatin. While the CI was above unity at the lowest fraction of cell affected, this slight deflection above one suggests that there is only a slight degree of antagonism between cisplatin and IR in the absence of ATM. Importantly, the shape of the curve obtained with the ATM cells is similar to that obtained with the MO59K cells while the MO59J cells display a dramatically different curve. This suggests that the reduction in ATM levels observed in MO59J cells can not account for the difference in synergism observed at high total doses which affect a larger fraction of cells, but may account, in part, for the decrease in antagonism observed at lower fractions of cells affected.

Figure 3.

Minimal interaction of cisplatin and IR in ATM cells. A: Cells were treated with cisplatin and plated into colony forming assays as described in “Materials and Methods”. Cell viability was determined by expressing the number of colonies as a percentage of the number of colonies present in mock treated control plates. B: Combined cisplatin and IR treatment was performed as described in “Materials and Methods”. Combination indices were calculated from at least three separate experiments and averages and standard errors plotted versus fraction of cells affected.

Inhibition of DNA-PKcs by terminal cisplatin-DNA lesions in vitro

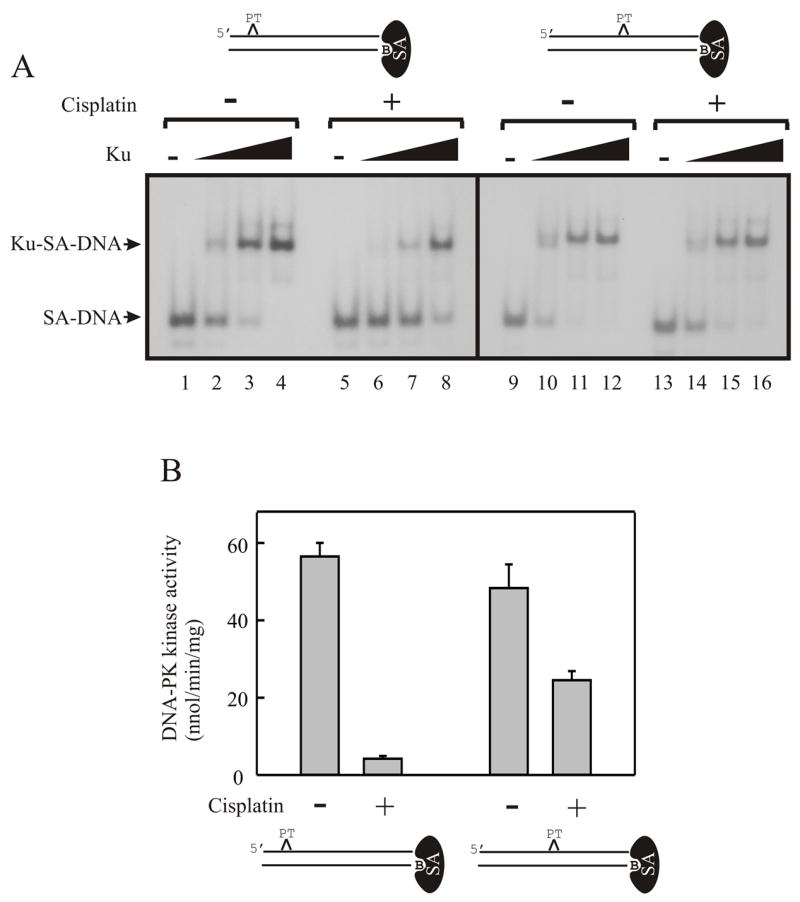

The data obtained in our cell culture model for the cisplatin-IR interaction suggest that a functional NHEJ pathway and the ability to signal DSBs are required for the synergistic activity between these two agents. An in vitro approach was utilized to directly address how the NHEJ pathway responds to the presence of compound lesions, in this case cisplatin-DNA adducts, in proximity of a DNA double-strand break. We assessed the ability of extracts prepared from NHEJ competent cells to catalyze NHEJ on DNA substrates containing a single site specific cisplatin lesion in close proximity to the DNA double-strand break. To first assess the effect of the position of the cisplatin lesion with respect to the DNA termini on activities required for NHEJ, a series of in vitro analyses were performed using either purified Ku or heterotrimeric DNA-PK and short, duplex DNA substrates. We designed the DNA substrates to contain a single cisplatin 1,2d-(GpG) adduct at varying distances from the terminus where DNA-PK could bind. DNA-PK was blocked from binding to the opposite terminus by a streptavidin bound to the 5′ biotin present on the undamaged, complementary DNA strand of the duplex 22,23,46. The results of the Ku binding studies demonstrated that when using a DNA substrate which restricted binding to one terminus, the position of the cisplatin lesion from the accessible terminus altered the affinity of Ku for the DNA substrate. When the lesion was present 7 base pairs from the terminus there was a 50% reduction in Ku binding at subsaturating concentrations of Ku. There is minimal reduction in Ku binding on a DNA substrate where the lesion was positioned 15 base pairs from the terminus (Figure 4A). The ability of the DNA to activate DNA-PKcs also revealed that the presence and position of the cisplatin lesion inhibited kinase activity (Figure 4B). With the lesion positioned 7 base pairs from the terminus, there was a 90% reduction in kinase specific activity, while a 50% reduction was observed when the lesion was placed 15 base pairs from the terminus.

Figure 4.

Distance of cisplatin-lesion from the DNA terminus alters Ku binding and DNA-PK activation. A: Electrophoretic mobility shift analyses were performed using the streptavidin blocked 30-bp duplex DNA substrates with the site-specific cisplatin DNA adduct. The position of the adducts relative to the termini are depicted in the figure. Reactions were initiated with the addition of 0, 16, 50 and 150 fmol of purified Ku (Lanes 1–4, 5–8, 9–12 and 13–16 respectively). Reactions were incubated for 30 minutes on ice and the protein-DNA complexes were resolved by 4% Native PAGE. The products were visualized and quantified by PhosphorImager analysis. B: DNA-PK activation assays were performed as described in “Materials and Methods”. The streptavidin-blocked DNA substrates used in each assay are depicted below the graph. Data are presented as the average with standard errors from three separate experiments, each with triplicate determinations for an n=9.

Inhibition of NHEJ by terminal cisplatin-DNA lesions in vitro

As the presence of a single cisplatin adduct has been shown to reduce the kinase activity of DNA-PK by 90%, we were interested in determining the effect of the terminal cisplatin-lesion on the ability to perform NHEJ. If the cisplatin lesion is processed by NHEJ machinery, one might expect to observe a slight reduction in the ability to join DNA termini with cisplatin lesions. If there is no processing of the lesions, a significant reduction in NHEJ would be expected, as DNA-PK catalytic activity is required for NHEJ 31. To this end, an in vitro assay was employed to test the ability of HeLa cell extracts to perform end-joining of a DNA substrate that was either unmodified or contained a single intrastrand 1,2d-(GpG) cisplatin adduct 7 base pairs distal to the double-strand DNA break.

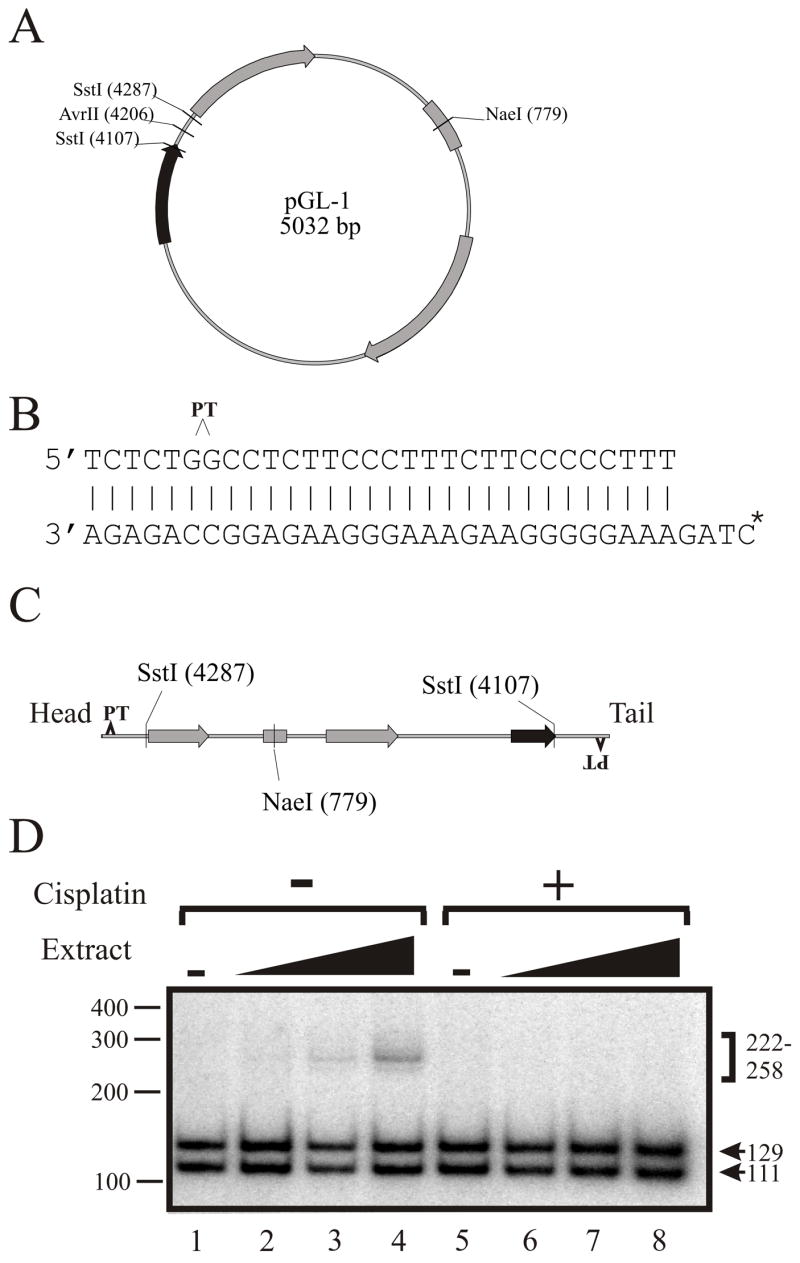

The DNA substrate was constructed from a 5-kbp plasmid that contained a single Avr II restriction site flanked by two Sst 1 sites (Figure 5A). The 30-mer linker molecule was based on the duplex DNA used in Figure 4 and contained a single cisplatin adduct site but was modified to contain an AvrII/XbaI sticky end. The 34 base complementary DNA strand was 5′-labeled with [γ-32P] ATP (Figure 5B). The double-stranded 30-mers, cisplatin damaged or undamaged, were ligated to the plasmid at the Avr II site. This generated the linear NHEJ substrate containing a single cisplatin adduct 5 base pairs distal to the dsDNA ends and the 32P-radiolabel 34 bases internal from each termini. Sst 1 digestion of an unjoined molecule produces products of 111 and 129 bases termed the head and tail, respectively (Figure 5C). NHEJ of the substrate can be envisioned in a variety of orientations; head to head, head to tail, and tail to tail, each generating a different sized product; 222, 240, and 258 base pairs respectively. This design presented several advantages, including the ability to ensure that every 32P-labeled DNA end contained one cisplatin adduct at a defined location, and that the control substrate was identical except for the absence of cisplatin damage. NHEJ reactions were performed with each substrate and the results are presented in Figure 5D. Upon addition of the cell free extract to reactions containing the undamaged DNA substrate, the expected ligation products were observed and showed an increase with increasing concentration of extract (Lanes 2–4). Dramatically, there was no detectable end-joining of substrate containing the cisplatin lesions (Lanes 6–8). The addition of wortmannin, an inhibitor of DNA-PK 47, completely blocked the end-joining reaction of the non-cisplatin treated DNA, demonstrating that joining is catalyzed by the DNA-PK dependant NHEJ pathway (data not shown). In order to optimize the reaction a variety of conditions were employed, including an increased substrate concentration. This increased the ligation of the undamaged DNA substrate 7-fold from that observed and still resulted in no end-joining with the DNA substrate containing the cisplatin adduct (data not shown). Initial time course experiments were performed and demonstrated an increase in joining of the control substrate with increased time with no joining of cisplatin damaged DNA being observed (data not shown). We also performed mixing experiments in which the cisplatin damaged and undamaged DNA substrates were combined. The results demonstrated that the cisplatin-damaged DNA substrate did not inhibit joining of the undamaged DNA substrate (data not shown). Together, these data suggest that in a cell the presence of a cisplatin lesion at a DNA terminus will result in a persistent DNA DSB, but may not significantly inhibit NHEJ catalyzed joining of DNA DSBs that do not have a cisplatin lesion in close proximity to the termini.

Figure 5.

Cisplatin lesions on DNA termini abrogate NHEJ catalyzed repair of DNA DSBs. A: pGL-1 plasmid map showing a single Avr II site flanked by two Sst 1 sites. B: SJC1.5C-Xba was 5′ end-labeled with 32P and annealed to SJC1.5 that was damaged with cisplatin or undamaged. The position of the cisplatin site is indicated by the carat. C: The 30/34 duplex DNA, with or without the cisplatin adduct, was ligated to pGL-1 linearized with Avr II as described in “Materials and Methods” and the product is depicted. Sst1 digestion of the linear DNA substrate would yield products of 111 (head) and 129 bps (tail). D: NHEJ reactions (20 μl) contained 6 fmol of DNA substrate and 0, 32, 80, or 160 μg of HeLa cell-free extract. Reactions were performed with either undamaged DNA (Lanes 1–4) or cisplatin damaged DNA (Lanes 5–8). Following digestion of the products with Sst1, ligation products were resolved on 10% Native PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. The arrows denote the unligated head (H) and tail (T) products of 111 and 129 bps respectively, and the bracket denotes ligation products of HH, HT or TH, and TT (222, 240, and 258 respectively).

Discussion

In this report we have investigated the mechanism by which cisplatin sensitizes cells to IR treatment. Cisplatin, in conjunction with IR, is under intense investigation in the treatment of a variety of cancers 48–51. Clinical trials of cervical cancer have demonstrated the utility of this combined treatment, increasing survival and disease free intervals, such that it is now part of the standard care for the treatment of cervical cancers 2,3.

While successful clinically for a subset of cancer types, only recently has the molecular mechanism of the radiosensitization activity of cisplatin been studied. This is at least in part a result of more recent advances in our understanding of the many pathways involved in signaling the cellular response to DNA damage and our detailed understanding of the mechanisms involved in repairing various types of DNA damage. An analysis of DSB formation revealed that the number of IR-induced DNA DSBs was largely independent of cisplatin pretreatment 52. It was convincingly demonstrated that the repair of IR induced DNA DSBs was altered by pretreatment with cisplatin, with a clear dose effect being observed 5. The authors demonstrated that low concentrations of cisplatin resulted in stimulation of DSB repair, while inhibition was only observed at higher doses of cisplatin 5. These results are consistent with the median effect analysis results in this study where antagonism is observed at low combined doses and synergy is observed at high doses in cells with a functional NHEJ pathway (Figures 1 and 2). The results we have obtained with DNA-PK deficient cells suggest a role for NHEJ in cisplatin-dependent radiosensitization. These results are supported by previous data which demonstrated that there was no dependence of cisplatin on the repair of single-strand DNA breaks 5, consistent with the role of NHEJ in processing DNA DSB’s. A role for NHEJ in cisplatin radiosensitization has been observed in Ku null cells which were inefficiently sensitized to IR by cisplatin, however, the investigators could not rule out a limitation of their assay in detecting differences in viability as a result of the extreme sensitivity of the Ku null cells to IR 4. The use of median effect analysis allowed us to circumvent this limitation and using DNA-PK null cells, demonstrate the influence of NHEJ on the interaction of cisplatin and IR over the entire range of cells affected. The observation that ATM cells also are defective in cisplatin-dependent radiosensitization further supports the NHEJ pathway in the potentiation of this effect.

DNA damage signaling pathways have been studied in a variety of systems and involve an array of sensor, mediator and effector proteins 53,54. The phosphotidylinositol 3-kinase like kinase (PIKK) family members ATM and ATR are thought to be the major transducers of DNA damage capable of phosphorylating a series of downstream target proteins, including the chk2 and chk1 kinases, in response to DNA damage. ATM is primarily responsible for signaling DNA DSBs, while ATR signals stalled replication forks and UV induced DNA damage. The combination of IR and cisplatin treatment is likely to result in the activation of both pathways, as cisplatin has been shown to increase ATR activity 55, and our data suggest that the final effect will depend on the total dose. The differential interactions seen between cisplatin and IR as a function of doses, antagonism at low doses and synergy at high doses (Figure 2B), could be the result of cross-talk between the two signaling pathways. At low doses of cisplatin, activation of the ATR pathway resulting in down-stream activation of chk1, phosphorylation of p53 and inhibition of cdc25A phosphatase activity could contribute to the subsequent sensing of IR induced DNA DSBs via ATM. ATM activation and chk2 phosphorylation would also result in p53 activation and cdc25A inhibition. This overlap could be envisioned to result in antagonism, as the sensor and effector pathways leading to establishing cell cycle checkpoints would result in increased survival of the cells treated with both agents compared to the individual treatments. In contrast, at higher combined doses, there are a greater number of cisplatin-DNA lesions when the cells are exposed to IR treatment. Assuming a completely random distribution of IR induced DNA DSBs following cisplatin treatment, we calculated that approximately 0.01% of the treated cells would have a cisplatin lesion within 7-bps of a DNA terminus generated from the DSB at the levels of cisplatin and doses of IR used in this study. However, previously published DNA suggest that the assumption of random IR induced DNA double strand breaks of cisplatin damaged DNA may be incorrect. While the total number of DNA DSBs was not affected by cisplatin treatment, the DNA extractability was altered 52, which indicates that there was some, yet to be described, change in the DNA or its association with nuclear proteins. We propose that the position of an IR induced DNA DSBs is altered such that the breaks occur within the vicinity of a preexisting cisplatin lesion. This hypothesis is supported by in vitro studies using the radiomimetic agent bleomycin which demonstrated that the positions of the bleomycin induced DNA DSBs were altered when the DNA was pretreated with cisplatin 56. This supposition is also supported circumstantially in experiments which demonstrate that the order of treatment is critical as cisplatin must be administered prior to IR treatment from maximum synergy 40. If the position of IR induced DNA DSBs are also modified dependent on cisplatin, then the substrates for NHEJ catalyzed repair of the DSBs can be influenced by the cisplatin lesion. Therefore, at higher cisplatin-DNA adduct levels and higher doses of IR, the likelihood that a DNA DSB occurs in the vicinity of a cisplatin lesion significantly increases. Our in vitro results demonstrate that this lesion represents an absolute block to NHEJ which in vivo will represent a persistent DNA DSB. Considering that a single persistent DNA DSB may be sufficient to induce cell death 57, the presence of a cisplatin-DNA lesion near a terminus would be expected to be lethal to the cell. The in vitro data of kinase activation (Figure 4) confirms the importance of cisplatin adduct position with respect to the DNA terminus 23. Clearly the effect of adduct position on NHEJ catalyzed is an important issue to be addressed.

The inability of the NHEJ pathway to process a cisplatin lesion in the vicinity of a DNA DSB has numerous interesting ramifications, the first of which is that these lesions are irreparable and will persist until the cell dies. This model is supported by the results of the median effect analysis revealing the lack of interaction between cisplatin and IR in DNA-PK null cells. The finding that there was no synergism in the DNA-PK null cells indicates that a functional NHEJ pathway is required for cisplatin dependent radiosensitization. What remain unknown is the role other DSB repair pathways potentially play in repairing compound lesions. If other pathways are capable of repairing a compound cisplatin-DNA-DSB lesion, for example, homologous recombination, these would reduce the degree of synergy. Interestingly, recent evidence has demonstrated a competition between NHEJ and homologous recombination (HR) in the repair of DNA DSBs 58. It was demonstrated using a specific inhibitor of DNA-PK, IC86621, that inactivation of DNA-PKcs results in decreased DSB induced repair via HR. The authors concluded that an inactive DNA-PKcs positioned at a DNA terminus could inhibit both NHEJ and HR as a result of the lack of autophosphorylation and dissociation of the subunit from the DNA end. The fact that a terminal cisplatin lesion results in inhibition of DNA-PKcs catalyzed kinase and autophosphorylation activity59 60, indicates that both NHEJ and HR catalyzed repair of DNA DSBs containing cisplatin lesions would be inhibited and therefore contribute to the radiosensitization activity of cisplatin.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatment

Cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with L-glutamine (Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA), penicillin/streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals). Incubations were performed at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. Cisplatin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to complete media at the indicated concentration for 4 hours at 37°C. Following incubation, the media containing cisplatin was removed and replaced with fresh complete media lacking cisplatin or PBS in the case of IR treatments. IR treatments were performed on ice using a HP Faxitron series X-ray generator (Hewlett-Packard, McMinnville, OR) to deliver the indicated doses. The X-rays were filtered through a 0.07mm aluminum filter resulting in a dose rate of 0.15Gy/min. Dosimetry was performed using a Radcal model 3036 dosimeter (Monrovia, CA). Prior to IR treatment, media was removed and replaced with PBS. Cell viability was assessed by a clonogenic colony forming assay. Briefly, cells were removed from the plates with trypsin, suspended in complete media, counted and plated at two densities in triplicate. Alternatively, cells were plated in triplicate, treated, and then placed directly into the incubator. Similar results were obtained with each procedure. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 7–14 days, stained with 1% methylene blue in 70% ethanol, washed with water and colonies containing at least 50 cells in size were counted using an Acolyte cell colony counter (Synbiosis, Cambridge, UK). Averages and standard errors were then plotted versus dose (IR or cisplatin), and LD50 values for each treatment were determined for each cell line.

Median effect analysis

Median effect analysis was employed to quantify the interaction of cisplatin and IR. For combined treatments, the ratio of IR dose to cisplatin dose was kept constant based on the LD50, and cells were treated with increasing total doses. A plot of the log of the total dose versus log of the reciprocal of the fraction of cells affected -1 yielded linear plots. The slope and y-intercepts from these plots were used to calculate the combination index (CI), as previously described 36.

Ku DNA binding assays

The sequences of the DNA oligonucleotides (IDT, Coralville, IA) used in this study are presented in Table 1. Oligonucleotides were 5′-labeled with [γ-32P] ATP, treated with cisplatin and purified as previously described 61. Biotinylated duplex DNA substrates (50 fmol) were incubated with 5 μg ImmunoPure streptavidin (Pierce, Rockford, IL) to block one end of the duplex DNA, thus restricting Ku binding to the opposite end 23. Ku protein was purified from HeLa cell free extracts, as previously described 60. Assays were performed by incubating increasing concentration of Ku with the indicated DNA substrates. The samples were then separated by 4% Native PAGE at room temperature for 2 hours at 125 volts. Gels were dried and the products visualized by autoradiography and quantified by PhosphorImager analysis using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) in volume integration mode.

Table 1.

Synthetic DNA substrates.

| Name | Sequence (5’-3’) | Length (bases) |

|---|---|---|

| SJC 1.1 | CCCCTCTCCTTCTTGGCCTCTTCCTTCCCC | 30 |

| SJC 1.2 | Biotin-GGGGAAGGAAGAGGCCAAGAAGGAGAGGGG | 30 |

| SJC 1.5 | TCTCTGGCCTCTTCCCTTTCTTCCCCCTTT | 30 |

| SJC 1.6 | Biotin-AAAGGGGGAAGAAAGGGAAGAGGCCAGAGA | 30 |

| SJC 1.5C-Xba | CTAGAAAGGGGGAAGAAAGGGAAGAGGCCAGAGA | 34 |

In vitro kinase assays

Assays to measure DNA-PK phosphorylation activity were performed as described previously 59. Briefly, reactions contained 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 8 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 2.5% glycerol, 0.2 mM EGTA, 400 μM synthetic p53-derived peptide substrate (EPPLSQEAFADLWKK) (Biosynthesis, Inc.) and 125 μM [γ-32P]ATP (0.5 μCi). To generate the streptavidin-bound duplex DNA oligomers used in the kinase assays, 500 fmol of the relevant undamaged and cisplatin-damaged DNA substrates was incubated with 0.1mg streptavidin in 20 mM KPi, pH 6.5 for 30 min at room temperature. Reactions were performed in a final volume of 20 μl and were initiated by the addition of increasing concentrations of purified DNA-PK, incubated at 30oC for 15 minutes, terminated with 15% acetic acid and spotted onto Whatman P81 filter paper. Filters were washed 5 x 5 min using 15% acetic acid, once briefly using 100% methanol, and radioactivity was quantified by PhosphorImager analysis in volume integration mode.

In vitro non-homologous end joining assay

Preparation of DNA substrates for non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) assays. The NHEJ substrate consisted of linearized pGL-1 (5032 bp) ligated with 32P-labeled 30-mer linker molecules containing a single intrastrand 1,2d (GpG) cisplatin adduct. Oligonucleotide SJC1.5 was platinated as previously described 61 and oligonucleotide SJC1.5C-Xba was 5′ labeled with [γ-32P] ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase and unincorporated nucleotide was removed using spin column chromatography. 32P-labeled SJC1.5C-Xba was annealed to platinated SJC1.5C (1:2 molar ratio) in buffer containing 10 mM Tris, pH 7.9, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT, followed by Hae III digestion (8 units; New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). Products were separated on 10 % native gels, and annealed. Hae III resistant DNA was isolated, eluted in buffer containing 0.3 M NaOAc, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% SDS, ethanol precipitated and stored in buffer containing 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA. A control unplatinated DNA was made in the same manner except was not digested with Hae III. The plasmid pGL-1 was linearized with Avr II (New England Biolabs) in buffer containing 10 mM Tris, pH 7.9, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT. Linker DNA with or without the cisplatin adduct, was mixed with plasmid DNA in a 2:1 molar ratio, ethanol precipitated, and resuspended in buffer containing 10 mM Tris, pH 7.9, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, 100 μg/ml BSA, T4 DNA ligase (300 units), Avr II (3 units) and Xba (7.5 units) (New England Biolabs). Ligation reactions proceeded for 16 hours at 18oC. Ligated product was separated from unligated linker by agarose gel electrophoresis (0.8%), followed by purification using gel extraction spin columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The NHEJ substrate was eluted and stored at -20oC in 10 mM Tris, pH 8.5. NHEJ reactions (20 μl) were performed in buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 40 mM KOAc, 1 mM Mg(0Ac)2, 1 mM DTT, 100 μg/ml BSA, 2 mM ATP and 5 μM IP6. Cell-free extracts were prepared from exponentially growing HeLa cells as previously described 62 Extracts were incubated for 10 min at 37oC prior to the addition of 32P- labeled NHEJ DNA substrate (6 fmol). Reactions proceeded for 2 hours at 37oC and were terminated by the addition of 500 μl of buffer containing 0.3 M NaOAc, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS and proteinase K (10 μg). These reactions were incubated at 45oC for 30 min after which the 32P-labeled DNA was extracted with 500 μl of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (50:49:1), and ethanol precipitated. The DNA products were digested with Sst 1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 min at 37oC and were analyzed by electrophoresis on 10% native polyacrylamide gels. Following electrophoresis for 2 hours at 160 V, gels were dried and quantified by PhosphorImager analysis.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01-CA82741 to JJT. We thank the other members of the laboratory for their helpful discussions and editing of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- DNA-PK

DNA dependent protein kinase

- DNA-PKcs

catalytic subunit of DNA-PK

- IR

ionizing radiation

- CI

combination index

- DSB

double strand break

- NHEJ

non-homologous end joining

- HR

homologous recombination

- MRN

Mre11/rad50/nbs1 complex

- NER

nucleotide excision repair

- Cisplatin

cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II)

- PIKK

phosphotidylinositol-3 kinase-like kinase

Reference List

- 1.Lieber MR, Ma YM, Pannicke U, Schwarz K. Mechanism and regulation of human non-homologous DNA end- joining. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2003;4:712–720. doi: 10.1038/nrm1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.HM Keys Cisplatin, radiation, and adjuvant hysterectomy compared with radiation and adjuvant hysterectomy for bulky stage IB cervical carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340:1144–1153. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rose PG. Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. NEngl JMed. 1999;341:708. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908263410924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myint WK, Ng C, Raaphorst GP. Examining the non-homologous repair process following cisplatin and radiation treatments. Int JRadiat Biol. 2002;78:417–424. doi: 10.1080/09553000110113047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dolling JA, Boreham DR, Brown DL, Mitchel REJ, Raaphorst GP. Modulation of radiation-induced strand break repair by cisplatin in mammalian cells. Int JRadiat Biol. 1998;74:61–69. doi: 10.1080/095530098141735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ormerod MG, O'Neill CF, Robertson D, Harrap KR. Cisplatin induces apoptosis in a human ovarian carcinoma cell line without concomitant internucleosomal degradation of DNA. Exp Cell Res. 1994;211:231–237. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henkels KM, Turchi JJ. Induction of apoptosis in cisplatin-sensitive and -resistant human ovarian cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4488–4492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henkels KM, Turchi JJ. Cisplatin-induced apoptosis proceeds by caspase-3-dependent and -independent pathways in cisplatin-resistant and -sensitive human ovarian cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3077–3083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calsou P, Salles B. Role of DNA repair in the mechanisms of cell resistance to alkylating agents and cisplatin. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1993;32:85–89. doi: 10.1007/BF00685607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koberle B, Grimaldi KA, Sunters A, Hartley JA, Kelland LR, Masters JR. DNA repair capacity and cisplatin sensitivity of human testis tumour cells. Int JCancer. 1997;70:551–555. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970304)70:5<551::aid-ijc10>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai GM, Ozols RF, Smyth JF, Young RC, Hamilton TC. Enhanced DNA repair and resistance to cisplatin in human ovarian cancer. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1988;37:4597–4600. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90325-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pouget JP, Douki T, Richard MJ, Cadet J. DNA damage induced in cells by gamma and UVA radiation as measured by HPLC/GC-MS and HPLC-EC and comet assay. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2000;13:541–549. doi: 10.1021/tx000020e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Utsumi H, Tano K, Takata M, Takeda S, Elkind MM. Requirement for repair of DNA double-strand breaks by homologous recombination in split-dose recovery. Radiat Res. 2001;155:680–686. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)155[0680:rfrodd]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson C, Jasin M. Coupled homologous and nonhomologous repair of a double-strand break preserves genomic integrity in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9068–9075. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.9068-9075.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang F, Han MG, Romanienko PJ, Jasin M. Homology-directed repair is a major double-strand break repair pathway in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5172–5177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sargent RG, Brenneman MA, Wilson JH. Repair of site-specific double-strand breaks in a mammalian chromosome by homologous and illegitimate recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:267–277. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.West R, Yaneva M, Lieber M. Productive and nonproductive complexes of Ku and DNA-dependent protein kinase at DNA termini. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5908–5920. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lees-Miller SP. The DNA-dependent protein kinase, DNA-PK: 10 years and no ends in sight. Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 1996;74:503–512. doi: 10.1139/o96-054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker JR, Corpina RA, Goldberg J. Structure of the Ku heterodimer bound to DNA and its implications for double-strand break repair. Nature. 2001;412:607–614. doi: 10.1038/35088000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeFazio LG, Stansel RM, Griffith JD, Chu G. Synapsis of DNA ends by DNA-dependent protein kinase. EMBO J. 2002;21:3192–3200. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottlieb TM, Jackson SP. The DNA-dependent protein kinase: requirement for DNA ends and association with Ku antigen. Cell. 1993;72:131–142. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90057-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoo S, Dynan WS. Geometry of a complex formed by double strand break repair proteins at a single DNA end: recruitment of DNA-PKcs induces inward translocation of Ku protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4679–4686. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.24.4679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turchi JJ, Henkels KM, Zhou Y. Cisplatin-DNA adducts inhibit translocation of the Ku subunits of DNA-PK. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4634–4641. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.23.4634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma YM, Pannicke U, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. Hairpin opening and overhang processing by an Artemis/DNA- dependent protein kinase complex in nonhomologous end joining and V(D)J recombination. Cell. 2002;108:781–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turchi JJ, Huang L, Murante RS, Kim Y, Bambara RA. Enzymatic completion of mammalian lagging-strand DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9803–9807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murante RS, Huang L, Turchi JJ, Bambara RA. The calf 5′ to 3′-exonuclease is also an endonuclease with both activities dependent on primers annealed upstream of the point of cleavage. JBiol Chem. 1994;269:1191–1196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carney JP, Maser RS, Olivares H, Davis EM, Le Beau M, Yates JR, Hays L, Morgan WF, Petrini JHJ. The hMre11/hRad50 protein complex and Nijmegen breakage syndrome: Linkage of double-strand break repair to the cellular DNA damage response. Cell. 1998;93:477–486. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chamankhah M, Xiao W. Formation of the yeast Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 complex is correlated with DNA repair and telomere maintenance. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2072–2079. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.10.2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Jager M, Dronkert MLG, Modesti M, Beerens CEMT, Kanaar R, van Gent DC. DNA-binding and strand-annealing activities of human Mre11: implications for its roles in DNA double-strand break repair pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1317–1325. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.6.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trujillo KM, Yuan SSF, Lee EYHP, Sung P. Nuclease activities in a complex of human recombination and DNA repair factors Rad50, Mre11, and p95. JBiol Chem. 1998;273:21447–21450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baumann P, West SC. DNA end-joining catalyzed by human cell-free extracts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14066–14070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Critchlow SE, Bowater RP, Jackson SP. Mammalian DNA double-strand break repair protein XRCC4 interacts with DNA ligase IV. Current Biology. 1997;7:588–598. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McElhinny SAN, Snowden CM, McCarville J, Ramsden DA. Ku recruits the XRCC4-ligase IV complex to DNA ends. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2996–3003. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.2996-3003.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu YP, Wang W, Ding Q, Ye RQ, Chen D, Merkle D, Schriemer D, Meek K, Lees-Miller SP. DNA-PK phosphorylation sites in XRCC4 are not required for survival after radiation or for V(D)J recombination. DNA Repair. 2003;2:1239–1252. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(03)00143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allalunis-Turner MJ, Barron GM, Day RS, Dobler KD, Mirzayans R. Isolation of 2 cell-lines from a human-malignant glioma specimen differing in sensitivity to radiation and chemotherapeutic drugs. Radiat Res. 1993;134:349–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative-analysis of dose-effect relationships - the combined effects of multiple-drugs or enzyme-inhibitors. Advances in Enzyme Regulation. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Azzariti A, Xu HM, Porcelli L, Paradiso A. The schedule-dependent enhanced cytotoxic activity of 7-ethyl- 10-hydroxy-camptothecin (SN-38) in combination with Gefitinib (Iressa,(TM), ZD1839) Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.George P, Bali P, Cohen P, Tao JG, Guo F, Sigua C, Vishvanath A, Fiskus W, Scuto A, Annavarapu S, Moscinski L, Bhalla K. Cotreatment with 17-allylamino-demethoxygeldanamycin and FLT-3 kinase inhibitor PKC412 is highly effective against human acute myelogenous leukemia cells with mutant FLT-3. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3645–3652. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maggio SC, Rosato RR, Kramer LB, Dai Y, Rahmani M, Paik DS, Czarnik AC, Payne SG, Spiegel S, Grant S. The histone deacetylase inhibitor MS-275 interacts synergistically with fludarabine to induce apoptosis in human leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2590–2600. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorodetsky R, Levy-Agababa F, Mou X, Vexler A. Combination of cisplatin and radiation in cell culture: effect of duration of exposure to drug and timing of irradiation. IntJCancer. 1998;75:635–642. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980209)75:4<635::aid-ijc23>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raaphorst GP, Wang G, Stewart D, Ng CE. Concomitant low dose-rate irradiation and cisplatin treatment in ovarian carcinoma cell lines sensitive and resistant to cisplatin treatment. Int JRadiat Biol. 1996;69:623–631. doi: 10.1080/095530096145634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilkins DE, Ng CE, Raaphorst GP. Cell cycle perturbations in cisplatin-sensitive and resistant human ovarian carcinoma cells following treatment with cisplatin and low dose rate irradiation. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1997;40:159–166. doi: 10.1007/s002800050641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chan DW, Gately DP, Urban S, Galloway AM, Lees-Miller SP, Yen T, Allalunis-Turner J. Lack of correlation between ATM protein expression and tumour cell radiosensitivity. Int JRadiat Biol. 1998;74:217–224. doi: 10.1080/095530098141591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iliakis G, Wang Y, Guan J, Wang HC. DNA damage checkpoint control in cells exposed to ionizing radiation. ONC. 2003;22:5834–5847. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Canman CE, Lim DS, Cimprich KA, Taya Y, Tamai K, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Kastan MB, Siliciano JD. Activation of the ATM kinase by ionizing radiation and phosphorylation of p53. Science. 1998;281:1677–1679. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoo S, Kimzey A, Dynan WS. Photocross-linking of an oriented DNA repair complex - Ku bound at a single DNA end. JBiol Chem. 1999;274:20034–20039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.20034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hashimoto M, Rao S, Tokuno O, Yamamoto KI, Takata M, Takeda S, Utsumi H. DNA-PK: the major target for wortmannin-mediated radiosensitization by the inhibition of DSB repair via NHEJ pathway. JRadiat Res(Tokyo) 2003;44:151–159. doi: 10.1269/jrr.44.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Solomon B, Ball DL, Richardson G, Smith JG, Millward M, MacManus M, Michael M, Wirth A, O'Kane C, Muceniekas L, Ryan G, Rischin D. Phase I/II study of concurrent twice-weekly paclitaxel and weekly cisplatin with radiation therapy for stage III non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2003;41:353–361. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martenson JA, Vigliotti APG, Pitot HC, Geeraerts LH, Sargent DJ, Haddock MG, Ghosh C, Keppen MD, Fitch TR, Goldberg RM. A phase I study of radiation therapy and twice-weekly gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2003;55:1305–1310. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sood BM, Timmins PF, Gorla GR, Garg M, Anderson PS, Vikram B, Goldberg GL. Concomitant cisplatin and extended field radiation therapy in patients with cervical and endometrial cancer. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2002;12:459–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenthal DI, Yom S, Liu L, Machtay M, Algazy K, Weber RS, Weinstein GS, Chalian AA, Miller LK, Rockwell K, Tonda M, Schnipper E, Hershock D. A Phase I study of SPI-077 (Stealth((R)) liposomal cisplatin) concurrent with radiation therapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2002;20:343–349. doi: 10.1023/a:1016201732368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Groen HJ, Sleijfer S, Meijer C, Kampinga HH, Konings AW, de Vries EG, Mulder NH. Carboplatin- and cisplatin-induced potentiation of moderate-dose radiation cytotoxicity in human lung cancer cell lines. British Journal of Cancer. 1995;72:1406–1411. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang J, Yu YN, Hamrick HE, Duerksen-Hughes PJ. ATM, ATR and DNA-PK: initiators of the cellular genotoxic stress responses. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1571–1580. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Durocher D, Jackson SP. DNA-PK, ATM and ATR as sensors of DNA damage: variations on a theme? Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2001;13:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yazlovitskaya EM, Persons DL. Inhibition of cisplatin-induced ATR activity and enhanced sensitivity to cisplatin. Anticancer Research. 2003;23:2275–2279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mascharak PK, Sugiura Y, Kuwahara J, Suzuki T, Lippard S. Alteration and activation of sequence-specific cleavage of DNA by bleomycin in the presence of the antitumor drug cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:6795–6798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.22.6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang LC, Clarkin KC, Wahl GM. Sensitivity and selectivity of the DNA damage sensor responsible for activating p53-dependent G(1) arrest. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4827–4832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allen C, Halbrook J, Nickoloff JA. Interactive competition between homologous recombination and non-homologous end joining. Molecular Cancer Research. 2003;1:913–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turchi JJ, Patrick SM, Henkels KM. Mechanism of DNA-dependent protein kinase inhibition by cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II)-damaged DNA. Biochemistry. 1997;36:7586–7593. doi: 10.1021/bi963124q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Turchi JJ, Henkels K. Human Ku autoantigen binds cisplatin-damaged DNA but fails to stimulate human DNA-activated protein kinase. JBiol Chem. 1996;271:13861–13867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Patrick SM, Turchi JJ. Replication Protein A (RPA) Binding to Duplex Cisplatin-damaged DNA Is Mediated through the Generation of Single-stranded DNA. JBiol Chem. 1999;274:14972–14978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wood RD, Robins P, Lindahl T. Complementation of the xeroderma pigmentosum DNA repair defect in cell-free extracts. Cell. 1988;53:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90491-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]