Abstract

Background

Mind-body practices that elicit the relaxation response (RR) have been used worldwide for millennia to prevent and treat disease. The RR is characterized by decreased oxygen consumption, increased exhaled nitric oxide, and reduced psychological distress. It is believed to be the counterpart of the stress response that exhibits a distinct pattern of physiology and transcriptional profile. We hypothesized that RR elicitation results in characteristic gene expression changes that can be used to measure physiological responses elicited by the RR in an unbiased fashion.

Methods/Principal Findings

We assessed whole blood transcriptional profiles in 19 healthy, long-term practitioners of daily RR practice (group M), 19 healthy controls (group N1), and 20 N1 individuals who completed 8 weeks of RR training (group N2). 2209 genes were differentially expressed in group M relative to group N1 (p<0.05) and 1561 genes in group N2 compared to group N1 (p<0.05). Importantly, 433 (p<10−10) of 2209 and 1561 differentially expressed genes were shared among long-term (M) and short-term practitioners (N2). Gene ontology and gene set enrichment analyses revealed significant alterations in cellular metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, generation of reactive oxygen species and response to oxidative stress in long-term and short-term practitioners of daily RR practice that may counteract cellular damage related to chronic psychological stress. A significant number of genes and pathways were confirmed in an independent validation set containing 5 N1 controls, 5 N2 short-term and 6 M long-term practitioners.

Conclusions/Significance

This study provides the first compelling evidence that the RR elicits specific gene expression changes in short-term and long-term practitioners. Our results suggest consistent and constitutive changes in gene expression resulting from RR may relate to long term physiological effects. Our study may stimulate new investigations into applying transcriptional profiling for accurately measuring RR and stress related responses in multiple disease settings.

Introduction

The relaxation response (RR) has been defined as a mind-body intervention that offsets the physiological effects caused by stress [1], [2]. The RR has been reported to be useful therapeutically (often as an adjunct to medical treatment) in numerous conditions that are caused or exacerbated by stress [3]–[6].

Mind-body approaches that elicit the RR include: various forms of meditation, repetitive prayer, yoga, tai chi, breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, biofeedback, guided imagery and Qi Gong [7]. One way that the RR can be elicited is when individuals repeat a word, sound, phrase, prayer or focus on their breathing with a disregard of intrusive everyday thoughts [2]. The non-pharmacological benefit of the RR on stress reduction and other physiological as well as pathological parameters has attracted significant interest in recent years to decipher the physiological effects of the RR. In addition to decreased oxygen consumption [8]–[10], other consistent physiologic changes observed in long-term practitioners of RR techniques include decreased carbon dioxide elimination, reduced blood pressure, heart and respiration rate [1], [2], [11], prominent low frequency heart rate oscillations [12] and alterations in cortical and subcortical brain regions [13], [14].

Despite these observations and the well-established clinical effects of RR-eliciting practices [15], [16], the mechanisms underlying the RR have not been identified. Similarly, the impact of the RR on gene expression and signaling pathways has not yet been explored in detail, although a transcriptional profiling study of Qi Gong [17] practitioners, another RR method, revealed apparent distinct gene expression differences between Qi Gong practitioners and age matched controls. It is likely that differences in gene expression may be an underlying factor in the physiologic and psychologic changes noted above. Toward that end, we conducted a study to explore the gene expression profile of healthy long-term practitioners versus healthy age and gender matched controls. As a further evaluation, we provided 8-weeks of RR training to the control subjects and re-assessed their gene expression.

Results

Patient characteristics

This study includes both cross sectional and an 8-week prospective design. Healthy adults were enrolled, comprising 2 groups: individuals with a long-term RR practice (group M; n = 19) or those with no prior RR experience (novice; group N1; n = 19). Group N1 novices, furthermore, underwent 8-weeks of RR training (Group N2; n = 20) for the prospective analysis. In the cross sectional study, we compare gene expression profiles (GEP) in whole blood between groups M and N1, whereas in the prospective study GEP is compared for each individual novice subject before and after RR experience, matched individuals of groups N1 versus N2 respectively.

Gene expression changes associated with the RR

Transcriptional differences between the different groups and within individuals before and after the RR are assessed by microarray analysis using Affymetrix HG-U133 Plus 2.0 genechips (www.affymetrix.com). This technology is a well established and reliable method to assess global gene expression differences [18]. Comparing group M (subjects with long term RR practice) to group N1 (subjects prior to RR training), we find statistically significant differential expression of 2209 genes; 1275 significantly up-regulated and 934 significantly down-regulated in M vs. N1. Additionally, 1561 genes are differentially expressed in novices after RR experience, N2 vs. N1; 874 significantly up-regulated and 687 significantly down-regulated. Comparison of gene lists from M vs. N1, N2 vs. N1 and M vs. N2 with Venn diagrams reveals significant overlap (Fig. 1a). Significance of overlaps is calculated using hypergeometric distributional assumption [19] and p-values are adjusted using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons [20]. Heatmaps were generated from genes in the intersecting areas of the Venn diagrams (Fig. 1b). We find 316 up-regulated and 279 down-regulated genes are differentially expressed in group M compared to both group N1 and N2; these changes in GEP are only observed in long-term RR practitioners. Similarly, 260 genes are up-regulated and 168 genes are down-regulated in both groups M and N2 compared to N1; they represent GEP changes characteristic of RR practice over at least 8 weeks.

Figure 1. Gene Ontology Analysis.

Analysis of differentially expressed genes: a) Venn diagrams: * indicates significant overlaps (p<106); b) Heatmaps of the 595 differentially regulated genes in both M vs. N1 and M vs. N2 (left) and the 418 differentially regulated genes in both M vs. N1 and N2 vs. N1; c) Heatmap of 15 genes in the intersection of all three groups (gene symbols listed on the right). In heatmaps, rows represent genes and columns represent samples from N1, N2, and M groups. Genes are clustered using row-normalized signals and mapped to the [−1,1] interval (shown in scales beneath each heatmap). Red and green represent high and low expression values, respectively.

Heatmaps generated using these genes exhibit consistent GEP changes across the three groups with a few samples in each group resembling the GEP of another group. To determine if any demographic characteristics (e.g. age, ethnicity , etc.) influences this observation, we clustered each group separately using the same set of genes. For each cluster analysis, we calculated the significance of observing a characteristic among the samples in the subgroups formed. We found that number of times M subjects reported eliciting the RR per week was significantly associated with the subgroups formed when M samples were clustered using genes differentially expressed in long term RR practitioners only. Specifically, there were 316 up-regulated and 279 down-regulated genes differentially expressed in group M compared to both group N1 and N2; (Fig. 1b). All remaining cluster analyses revealed no such significant influence of demographic characteristics (see online supplementary data).

Finally, the intersection of all 3 areas (M vs. N1, N2 vs. N1 and M vs. N2) identifies genes with expression behavior that is monotonically changed between N1 to N2 to M (Fig. 1c). These results clearly demonstrate that short term as well as long term RR practice lead to distinct and consistent gene expression changes in hematopoietic cells.

Signaling pathways modulated by the RR

We performed Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer (EASE) analysis [21] using M vs. N1, and N2 vs. N1 data-sets, to identify Gene Ontology (GO) categories where specific genes in these data occur more often than would be expected by random distribution of genes. These findings (and those of the validation data-set below) are summarized in Table 1, where select over-represented GO categories are listed along with specific genes differentially expressed in our data-sets. These categories include oxidative phosphorylation, ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolism, nuclear messenger RNA (mRNA) splicing, ribosomes, metabolic processes, regulation of apoptosis, NF-κB pathways, cysteine-type endo-peptidase activity and antigen processing. Most are significant in both long-term (M vs. N1) and short-term (N2 vs. N1) practitioners of daily RR practice (see Table).

Table 1. Gene Ontology Categories.

| SELECTED GENE ONTOLOGY CATEGORY | Original Data-set (n = 58) | Validation Data-set (n = 16) | ||

| M vs. N1 (2209) | N2 vs. N1 (1561) | M vs. N1 (1846) | N2 vs. N1 (2390) | |

| OXIDATIVE PHOSPHORYLATION (84) | 20† | 7 | 7 | 20† |

| ATP5E;ATP5L; COX5B, COX7B; NDUFB2; UCRC; UQCRB | ATP5E; NDUFB2; UQCRC2 | ATP5L; NDUFB2; UQCRB | ATP5L; COX5B;COX7B; NDUFB2; UCRC; UQCRB;UQCRC2 | |

| UBIQUITIN-DEPENDENT PROTEIN CATABOLISM (127) | 19* | 16* | 21** | 17 |

| ANAPC4; PSMB2; PSMF1; USP14; USP48 | PSMB2; PSMF1; USP14 | ANAPC4; PSMB2; PSMF1; USP14; USP48 | ANAPC4; PSMB1; USP48 | |

| NUCLEAR MESSENGER RNA SPLICING, VIA SPLICOSOME (127) | 22** | 15* | 18* | 21* |

| HNRPH3; TARDBP; THOC2; U2AF2 | HNRPH3; TARDBP; THOC2 | TARDBP; THOC2; U2AF2 | HNRPH3; THOC2; U2AF2 | |

| RIBOSOME (171) | 64‡ | 20* | 31‡ | 33† |

| RPL13A; RPL23A; RPL37A; RPS27 | RPL13A; RPL23A; RPL37A; RPS27 | RPL13A; RPL37A; RPS27 | RPL23A;RPL37A; RPS27 | |

| PRIMARY METABOLISM (6379) | 667‡ | 477‡ | 574† | 694† |

| ADCY9; CLC; PCK2; PDHA1; SOD2 | ADCY9; CLC; KLF6; PCK2; PDHA1 | ADCY9; CLC | KLF6; SOD2 | |

| NEGATIVE REGULATION OF METABOLISM (238) | 31* | 24* | 30* | 35* |

| HDAC8; MDM4; PPARD; TH1L | MDM4; SIRT2; TH1L; ZBTB16 | ZBTB16 | TH1L; ZBTB16 | |

| REGULATION OF APOPTOSIS (343) | 38 | 37** | 48† | 42 |

| BIRC4; CFLAR; FAS; PRDX2; PRDX5 | BIRC4; CFLAR; HSP90B1; PRDX2; PRDX3 | CFLAR | CFLAR | |

| REGULATION OF I-kB KINASE/NF-Κ B CASCADE (83) | 12 | 14** | 14* | 13 |

| FASLG; HMOX1; TNFSF10 | FASLG; IKBKE; TNFSF15; TRAF6 | HMOX1 | IKBKE | |

| CYSTEINE-TYPE ENDO-PEPTIDASE ACTIVITY (105) | 16 | 13* | 17* | 18* |

| ATG4D; CASP2; CASP9 | CASP2; CASP7; CTSB | CASP2; CTSB | ATG4D | |

| ANTIGEN PROCESSING (34) | 9* | 11‡ | 8* | 13‡ |

| HFE; HLAC; LRAP | HFE; HLAC | HFE; HLAC | HFE; LRAP | |

Numbers in parentheses are the total number of genes per comparison for each data-set or the GO reference set. The number of differentially expressed genes with representative members in that GO category for each comparison and data-set are listed. Significance of EASE scores are indicated as follows: p<0.05*, p<0.01**, p<0.001†, p<0.0001‡.

Even though our analyses of differentially expressed genes and GO categories associated with RR practice meet widely accepted criteria for statistical significance, we were concerned about the relatively small fold changes that were observed (see Supplementary Methods). To address this issue we employed Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA). GSEA has proven to be useful for capturing subtle expression changes in complex gene signatures based on predefined gene sets or pathways [22]. As described above, we examined expression data for 2 comparisons, M vs. N1 and N2 vs. N1. The selected pathways or gene sets that are significantly enriched (False Discovery Rate (FDR)<50%, nominal p-value (NPV)< = 0.02) are shown in Figure 2, with gene sets for N2 vs. N1 and M vs. N1 in Fig 2A and Fig 2B respectively.

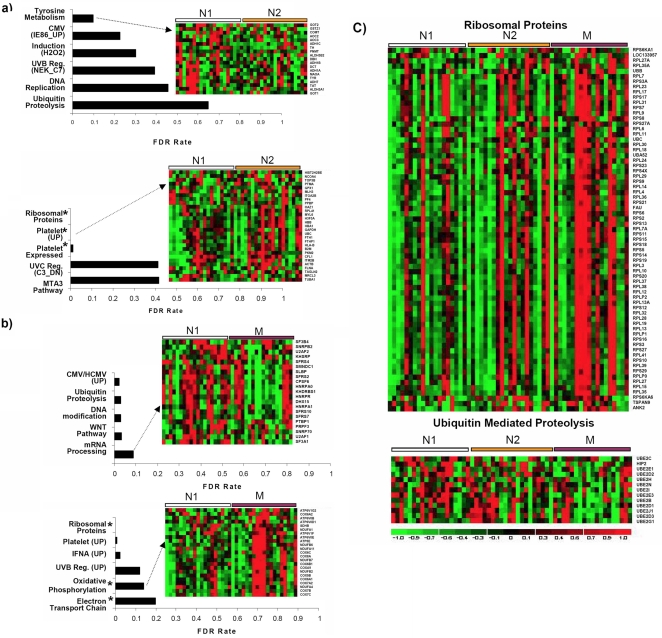

Figure 2. GSEA Analysis.

The analysis has been performed for >1200 predefined datasets using GSEA 2.0 software. Signal values for each gene are obtained by collapsing the probe values using max_probe algorithm. Representative datasets, significantly enriched (FDR<50%, or NPV< = 0.01) between any two groups and corresponding heatmaps (depicting relative gene expression changes of core enrichment) are shown in a) N2 vs. N1 and b) M vs. N1. Datasets that are enriched in both the original and validation analyses are marked with *. c) Heatmaps of ribosomal proteins and ubiquitin mediated proteolysis illustrate transitional trends in gene expression across the N1, N2 and M groups.

GSEA analysis of N2 vs. N1 showed highly significant enrichment in gene sets related to various cellular stressors/stress responses and metabolism. To a pronounced degree these observations complement the results of GO analysis presented in the Table, also depicting significant alterations in cellular response to stress, oxidative and primary metabolism. The transition effect of the RR from novice to short term (8 weeks) to long term RR practitioners has been denoted through a colorgram of ribosomal proteins and ubiquitin mediated proteolysis gene sets (Fig. 2C). Whereas expression of ribosomal genes is significantly upregulated in RR practitioners at 8 weeks and more pronounced in long term practitioners, ubiquitin mediated proteolysis gene expression in general shows an opposite trend. Closer inspection of the colorgrams for ribosomal proteins and Ub proteolysis gene sets shows some variation in the GEP in each subgroup (N1, N2 M). The GEP of a few N1 or N2 subjects resembles the GEP of M subjects and vice versa. To elucidate the association between GEP and subject characteristics (Race, Age, etc), we performed clustering of each subgroup separately (N1, M) using the enriched gene sets (Ribosomal and Ub Proteolysis). This analysis identified a subcluster in the N2 subgroup that has significant over-representation of Asian subjects (P value <0.05) when the clustering was performed using the ribosomal protein gene set. This observation needs further validation on a larger dataset as the current study contains only five Asian subjects. No other characteristic exhibited significant association with the ribosomal protein gene set. No significant association between the GEP profiles and subject characteristic was found when clustering was performed using the Ub proteolysis gene set. This analysis provides further insight into the stress response related genes that are influenced by RR practice.

Independent validation set analysis

As a validation of our results, we repeated the experimental and analysis procedures defined in the “Methods” section on a new set of samples consisting of 5 N1, 5 N2 and 6 M subjects. We found 1846 and 2390 probe sets differentially expressed between M vs. N1, and N2 vs. N1 groups. The validation data-set showed a significant (p<10−5) number of genes in common with the original analysis of 58 samples. We also found that 70–75% of all GO categories from the original analysis were retained in the validation set (p ∼0), and 30–65% of significantly over-represented GO categories were shared. Of note, biologically relevant GO categories such as oxidative phosphorylation, regulation of apoptosis, and antigen presentation, come up as significantly over-represented in both the original and validation analyses. Results of the validation set and comparison analyses can be found in the online supplementary data. In addition, validation GSEA analysis on N2 vs. N1 subjects shows enrichment of ribosomal proteins and platelet expressed gene sets and enrichment of ribosomal proteins, oxidative phosphorylation and electron transport chain gene sets in M vs. N1 subjects (Fig. 2A and 2B). The similarities between the original and validation results from GSEA analysis argues against random chance accounting for the observed enrichment of these gene sets.

Discussion

Results from our study indicate that there are distinct differences in the GEPs between individuals with many years of RR practice (group M) and those without such experience (group N1). Furthermore we find significant GEP changes within the same individuals before (N1) and after 8 weeks of RR training (N2). Finally, the changes in GEP found in M vs. N1, and those of N2 vs. N1, are to a great degree similar when assessed by analysis of differentially expressed genes, GO analysis and GSEA.

It is becoming increasingly clear that psychosocial stress can manifest as system-wide perturbations of cellular processes, generally increasing oxidative stress and promoting a pro-inflammatory milieu [23]–[25]. Stress associated changes in peripheral blood leukocyte expression of single genes have been identified [26]–[28]. More recently, chronic psychosocial stress has been associated with accelerated aging at the cellular level. Specifically, shortened telomeres, low telomerase activity, decreased anti-oxidant capacity and increased oxidative stress are correlated with increased psychosocial stress [29] and with increased vulnerability to a variety of disease states [30]. Stress-related changes in GEP have been demonstrated by microarray analysis in healthy subjects, including up-regulation of several cytokines/chemokines and their receptors [31], and in individuals suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, including inflammation, apoptosis and stress response [32] as well as metabolism and RNA processing pathways [33]. The pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-kappa B (NF-κB) which is activated by psychosocial stress has been identified as a potential link between stress and oxidative cellular activation [34].

The RR is clinically effective for ameliorating symptoms in a variety of stress-related disorders including cardiovascular, autoimmune and other inflammatory conditions and pain [15]. We hypothesize that RR elicitation is associated with systemic gene expression changes in molecular and biochemical pathways involved in cellular metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation/generation of reactive oxygen species and response to oxidative stress and that these changes to some degree serve to ameliorate the negative impact of stress. Genome-wide evaluation of PBL GEP is a reasonable approach to survey the transcriptional changes that are involved in elicitation of the RR. The GEP of RR practitioners presented here reveals altered gene expression in specific functional groups which suggest a greater capacity to respond to oxidative stress and the associated cellular damage. Genes including COX7B, UQCRB and CASP2 change in opposite direction from that in the stress response [31], [32].

Our findings are relatively consistent with those found in a study of Qi Gong [17], a practice that elicits the RR. In their study of 6 Qi Gong practitioners and 6 aged matched controls, practitioners had down-regulation of ubiquitin, proteasome, ribosomal protein and stress response genes and mixed up- and down-regulation of genes involved in apoptosis and immune function. We find a similar pattern of GO categories that are significantly over-represented in GO or enriched in GSEA in our cross sectional comparison, M vs. N1. However, in our data-set ribosomal proteins were up-regulated.

Overall, similar genomic pattern changes occurred in practitioners of a specific mind body technique (Qi Gong) as well as in our long-term practitioners who utilized different RR practices including Vipassna, mantra, mindfulness or transcendental meditation, breath focus, Kripalu or Kundalini Yoga, and repetitive prayer. This indicates there is a common RR state regardless of the techniques used to elicit it.

Our study is the first to prospectively evaluate GEP changes in individuals before and after a short-term (8 week) RR training which consequently enables an appreciation of the parallel GEP changes that occur with short- and/or long-term RR practice. Replications in larger cohorts are warranted. Future investigations could better define the therapeutic value and required duration of RR training to counter stress-related disorders.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Nineteen healthy practitioners of various RR eliciting techniques (including several types of meditation, Yoga, and repetitive prayer) participated (M group; n = 19). Years of practice averaged 9.4 years (5.0 sd) and ranged from 4 to 20 years. Twenty individuals without any prior RR eliciting experience served as controls (N group; n = 20).. As shown in Table 2, the M and N groups are matched with respect to age, gender, race, height, weight, and marital status, which do not exhibit significant difference between the groups (p>0.05, t- and chi-square test).

Table 2. Demographics.

| N group | M group | p-value | |

| Age | 36.68±6.22-3 | 37.21±6.93 | 0.81 |

| Race | 10 White, 4 Asian, | 16 White, 1 Asian, | 0.15 |

| 3 African American, | 2 African American, | ||

| 2 Hispanic | 0 Hispanic | ||

| Gender | 9 Male, 10 Female | 9 Male, 10 Female | 1.0 |

| Height | 66.32±3.73 | 68.79±4.22 | 0.06 |

| Weight | 152.47±24.40 | 153.58±16.82 | 0.87 |

| Marital Status | 4 Married, 1 Widowed, | 5 Married, 0 Widowed, | 0.73 |

| 3 Seperated/Divorced, | 4 Seperated/Divorced, | ||

| 11 Never Married | 10 Never Married |

The demographic characteristics for the N and M groups. The age, height, and weight p-values were calculated using t-test, whereas the race, gender, and marital status p-values were calculated using chi-square test. There were no significant differences across the groups

Protocol

The study protocol was approved by the Committee on Clinical Investigations at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), Boston MA. All subjects provided written informed consent and the study was conducted in the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) of the BIDMC. After providing written informed consent, participants were screened by a physician and had blood drawn to ensure good health. All participants completed a testing session in the GCRC. N1 (novice) subjects had 8-weeks of RR training, listened to a 20-minute RR-eliciting CD daily and returned to the GCRC for a repeat testing session (hereafter classified as the N2 group).

Relaxation-Response Training

N subjects received 8 weeks of RR training. Training included information about reducing daily stress, and a 20-minute elicitation of the RR [35]. Subjects randomized to the RR group received 8 weekly individual RR-training sessions from an experienced clinician as per our manualized research protocol [35]. The first session provided an educational overview of the stress response and the RR, instructions on how to elicit the RR, and a 20-minute guided RR experience. Sessions 2 through 8 consisted of a review of the subject's home practice card for compliance and a 20-minute guided RR experience.

During the RR elicitation in the weekly session, the subject was guided through a RR sequence including: diaphragmatic breathing, body scan, as well as mantra and mindfulness meditation, while subjects passively ignored intrusive thoughts. The specific CD guided the subject through the same sequence and has our clinical research studies and clinical practice for more than 15 years [35]. Subjects were asked to listen to the RR-eliciting CD once a day for 20 minutes at home.

To measure compliance, participants' daily home practice logs were reviewed each week and at the end of the 8 week training. These logs indicate that N subjects listened for an average of 17.5 minutes per day (3.7 sd) over 8-weeks.

Microarray Analysis

Following previously described protocols, the transcriptional profile of samples were probed using Affymetrix HG-U 133 Plus 2.0 chips representing over 47,000 transcripts and variants using more than 54,000 probesets. Scanned image output files were visually examined for major chip defects and hybridization artifacts and then analyzed with Affymetrix GeneChip Microarray Analysis Suite 5.0 (MAS5) software (Affymetrix). The image from each chip was scaled such that the 2% trimmed mean intensity value for all arrays was adjusted to target intensity and reported as a non-negative quantity. Chips used for subsequent analysis consisted of 19 M, 19 N1 and 20 N2 samples (one chip from the N1 group had insufficient signal values). A hierarchical clustering technique was used to construct an Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic-mean (UPGMA) tree using Pearson's correlation as the metric of similarity [36]. The expression data matrix was row-normalized for each gene prior to the application of average linkage clustering. When comparing 2 groups of samples to identify genes enriched in a given group, we used combination of three criteria. We considered genes with significantly different expression across the two groups using t-test (p<0.05) that further remained significant at a 5% false discovery rate (FDR) using permutation testing with 1,000 permutations [37], [38]. In order to finalize a set of genes significantly up-regulated in a given group compared to another group, among the genes that passed the aforementioned steps, we filtered the ones that are “present” in at least half of the samples in the enriched group using Affymetrix' MAS5 Presence/Absence (P/A) calls. We used a paired t-test when comparing samples in groups N1 and N2.

Data deposition: All data sets have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession nos. GSE10041 and GSM253663-253734).

Gene Ontology and Gene Set Enrichment Analyses

Differentially expressed genes between the 3 groups (N2 vs. N1, M vs. N1 and M vs. N2) were separately analyzed using EASE to identify biologically relevant categories that are over-represented in the input set [21]. EASE analyses tested each list against all genes on the chip and overrepresentation describes a group of genes belonging to a certain GO category that appear more often in the given input list than expected to occur if the distribution were random. GO categories that had EASE scores of 0.05 or lower were selected as significantly over-represented. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA 2.0 package http://www.broad.mit.edu/gsea/) was used to determine whether an a priori defined set of genes showed statistically significant, concordant differences between 2 groups (N2 vs. N1, and M vs. N1) in the context of known biological pathways. We tested expression values of all the genes in the relevant sample groups against 1687 gene sets obtained from the MSigDB2.0 for enrichment belonging to various metabolic pathways, chromosomal locations and functional sets (gene sets related to cancer/cancer cells are not included). The enriched gene sets have nominal p-value (NPV) less than 1% and False Discovery Rate (FDR) <50% after 100 random permutations. These criteria ensure that there is minimal chance of identifying false positives.

Supplementary Methods are located at http://bidmcgenomics.org/MIND_BODY_RR/(Login: benson) (Password: test1).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Mariola T. Milik and Jennifer M. Johnston for their contributions during the study.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: The study was funded by grants H75/CCH 19124, H75/CCH 123424 and R01 DP000339 (HB) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and M01 RR01032 (HB) from the National Institutes of Health (to Harvard-Thorndike BIDMC GCRC).

References

- 1.Wallace RK, Benson H, Wilson AF. A wakeful hypometabolic physiologic state. Am J Physiol. 1971;221:795–799. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1971.221.3.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson H, Beary JF, Carol MP. The relaxation response. Psychiatry. 1974;37:37–46. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1974.11023785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sternberg EM. Emotions and disease: from balance of humors to balance of molecules. Nat Med. 1997;3:264–267. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson H, Kotch JB, Crassweller KD. Stress and hypertension: interrelations and management. Cardiovasc Clin. 1978;9:113–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakao M, Myers P, Fricchione G, Zuttermeister PC, Barsky AJ, et al. Somatization and symptom reduction through a behavioral medicine intervention in a mind/body medicine clinic. Behav Med. 2001;26:169–176. doi: 10.1080/08964280109595764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benson H, Goodale IL. The relaxation response: your inborn capacity to counteract the harmful effects of stress. J Fla Med Assoc. 1981;68:265–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benson H. The relaxation response: Its subjective and objective historical precedents and physiology. TINS. 1983;6:281–284. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson H, Steinert RF, Greenwood MM, Klemchuk HM, Peterson NH. Continuous measurement of O2 consumption and CO2 elimination during a wakeful hypometabolic state. J Human Stress. 1975;1:37–44. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1975.9940402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kesterson J, Clinch NF. Metabolic rate, respiratory exchange ratio, and apneas during meditation. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:R632–638. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.256.3.R632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warrenburg S, Pagano RR, Woods M, Hlastala M. A comparison of somatic relaxation and EEG activity in classical progressive relaxation and transcendental meditation. J Behav Med. 1980;3:73–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00844915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beary JF, Benson H. A simple psychophysiologic technique which elicits the hypometabolic changes of the relaxation response. Psychosom Med. 1974;36:115–120. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197403000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng CK, Henry IC, Mietus JE, Hausdorff JM, Khalsa G, et al. Heart rate dynamics during three forms of meditation. Int J Cardiol. 2004;95:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazar SW, Bush G, Gollub RL, Fricchione GL, Khalsa G, et al. Functional brain mapping of the relaxation response and meditation. Neuroreport. 2000;11:1581–1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs GD, Benson H, Friedman R. Topographic EEG mapping of the relaxation response. Biofeedback Self Regul. 1996;21:121–129. doi: 10.1007/BF02284691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Astin JA, Shapiro SL, Eisenberg DM, Forys KL. Mind-body medicine: state of the science, implications for practice. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:131–147. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esch T, Fricchione GL, Stefano GB. The therapeutic use of the relaxation response in stress-related diseases. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9:RA23–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li QZ, Li P, Garcia GE, Johnson RJ, Feng L. Genomic profiling of neutrophil transcripts in Asian Qigong practitioners: a pilot study in gene regulation by mind-body interaction. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:29–39. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee NH, Saeed AI. Microarrays: an overview. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;353:265–300. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-229-7:265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivanova NB, Dimos JT, Schaniel C, Hackney JA, Moore KA, et al. A stem cell molecular signature. Science. 2002;298:601–604. doi: 10.1126/science.1073823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaffer J. Multiple hypothesis testing. Ann Rev Psych. 1995;46:561–584. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosack DA, Dennis G, Jr., Sherman BT, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with EASE. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R70. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-10-r70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irie M, Asami S, Nagata S, Miyata M, Kasai H. Psychological mediation of a type of oxidative DNA damage, 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine, in peripheral blood leukocytes of non-smoking and non-drinking workers. Psychother Psychosom. 2002;71:90–96. doi: 10.1159/000049351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamaguchi T, Shioji I, Sugimoto A, Yamaoka M. Psychological stress increases bilirubin metabolites in human urine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293:517–520. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng KC, Ariizumi M. Modulations of immune functions and oxidative status induced by noise stress. J Occup Health. 2007;49:32–38. doi: 10.1539/joh.49.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glaser R, Kennedy S, Lafuse WP, Bonneau RH, Speicher C, et al. Psychological stress-induced modulation of interleukin 2 receptor gene expression and interleukin 2 production in peripheral blood leukocytes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:707–712. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810200015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaser R, Lafuse WP, Bonneau RH, Atkinson C, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-associated modulation of proto-oncogene expression in human peripheral blood leukocytes. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107:525–529. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Platt JE, He X, Tang D, Slater J, Goldstein M. C-fos expression in vivo in human lymphocytes in response to stress. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1995;19:65–74. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(94)00105-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Adler NE, et al. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17312–17315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407162101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Epel ES, Lin J, Wilhelm FH, Wolkowitz OM, Cawthon R, et al. Cell aging in relation to stress arousal and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morita K, Saito T, Ohta M, Ohmori T, Kawai K, et al. Expression analysis of psychological stress-associated genes in peripheral blood leukocytes. Neurosci Lett. 2005;381:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zieker J, Zieker D, Jatzko A, Dietzsch J, Nieselt K, et al. Differential gene expression in peripheral blood of patients suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:116–118. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Segman RH, Shefi N, Goltser-Dubner T, Friedman N, Kaminski N, et al. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression profiles identify emergent post-traumatic stress disorder among trauma survivors. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:500–513, 425. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bierhaus A, Wolf J, Andrassy M, Rohleder N, Humpert PM, et al. A mechanism converting psychosocial stress into mononuclear cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1920–1925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438019100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dusek JA, Chang BH, Zaki J, Lazar S, Deykin A, et al. Association between oxygen consumption and nitric oxide production during the relaxation response. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:CR1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sneath PHA. 1973. Numerical taxonomy; the principles and practice of numerical classification (W. H. Freeman, San Francisco, CA)

- 37.Li C, Wong WH. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: expression index computation and outlier detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:31–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011404098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]