Abstract

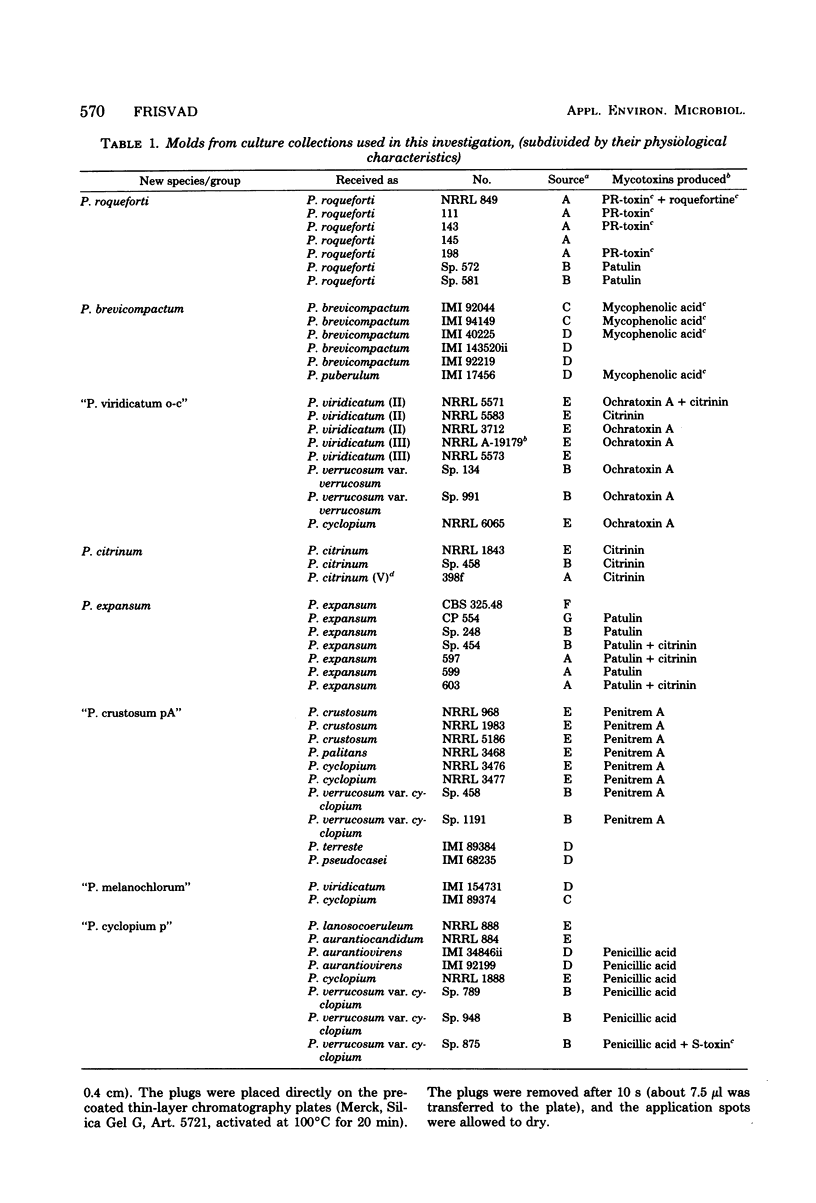

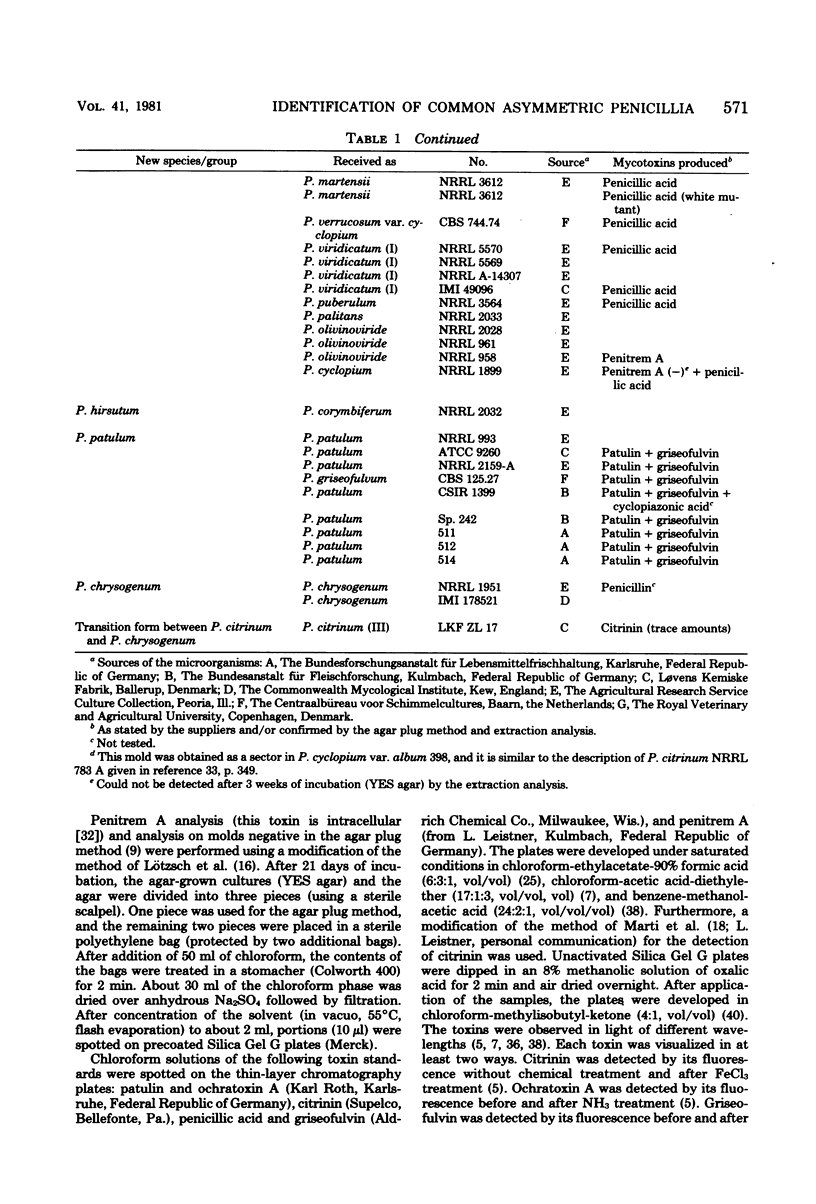

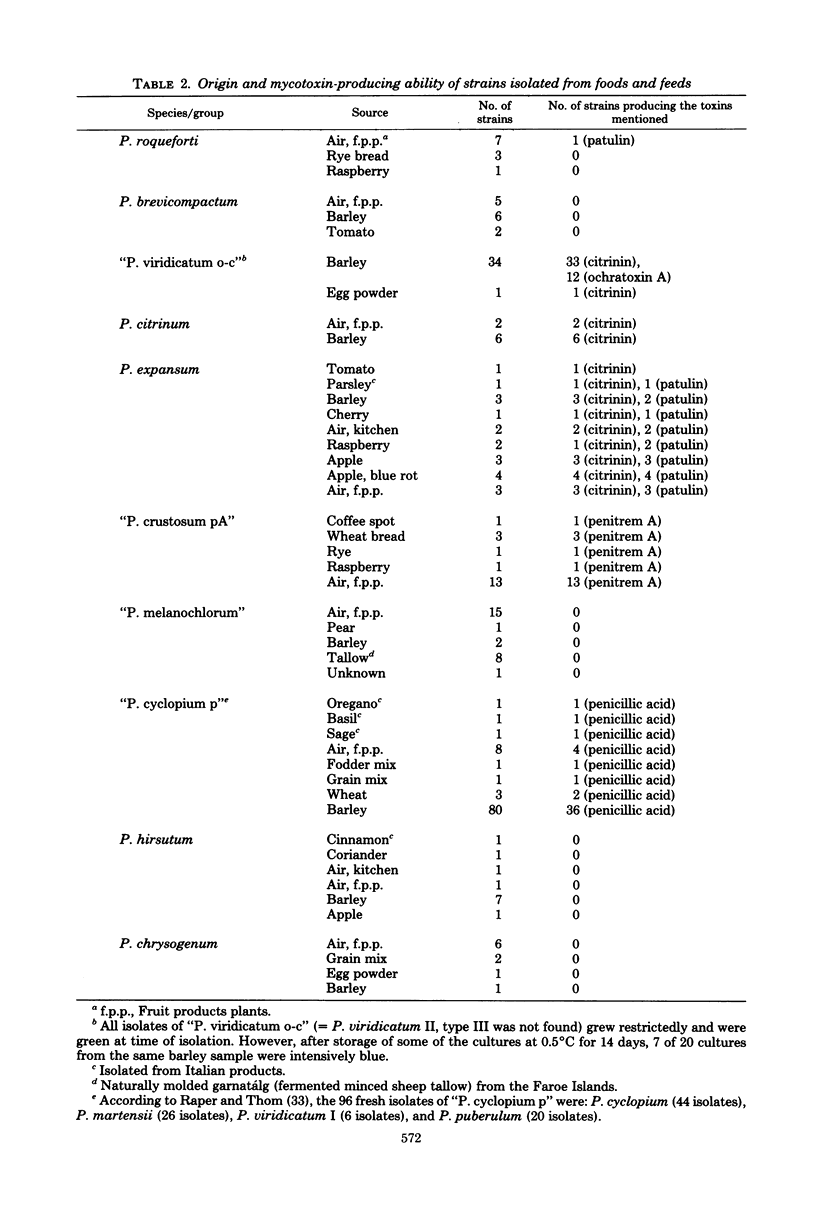

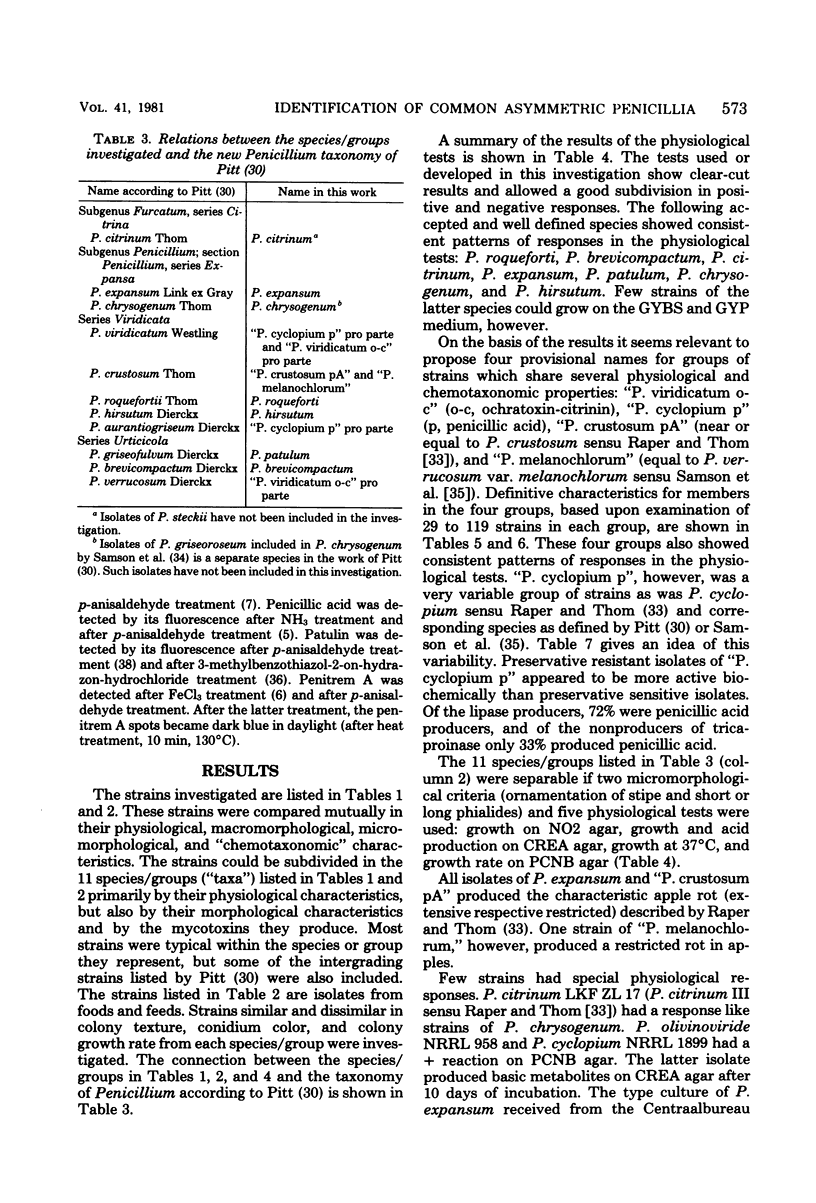

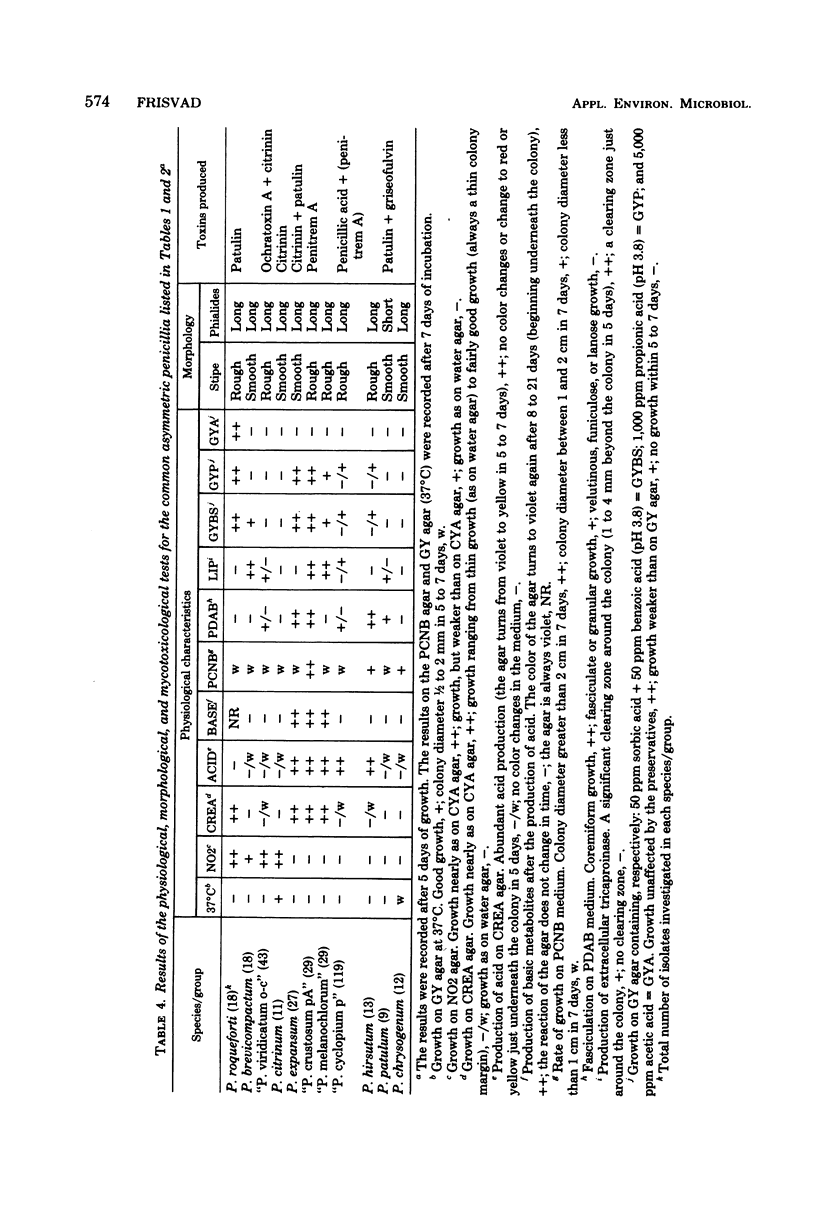

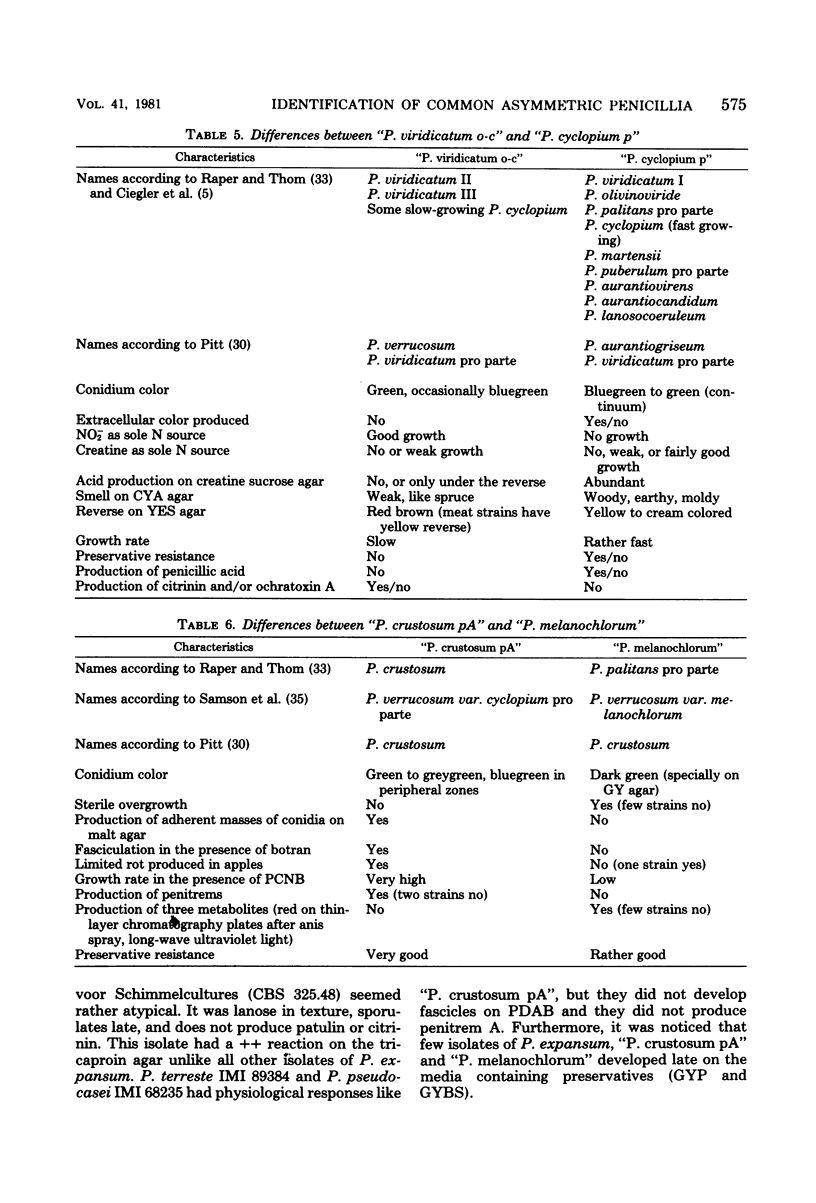

The taxonomy of the asymmetric (predominantly terverticillate) penicillia is based on morphological differences that leave identification difficult. The application of physiological criteria facilitated the identification of the common asymmetric penicillia investigated. Changes in the placement of some strains of these penicillia made the connection to mycotoxin-producing ability clearer. The classical criterion of conidium color was deemphasized and replaced by the following criteria: (i) growth on nitrite-sucrose agar and (ii) growth and acid (and subsequent base) production on creatine-sucrose agar (containing bromocresol purple). Other criteria used or developed were: (iii) growth on sorbic acid plus benzoic acid agar (50 + 50 ppm, pH 3.8), (iv) growth on an agar containing 1,000 ppm propionic acid (pH 3.8), (v) growth on an agar containing 0.5% acetic acid, (vi) growth at 37°C, (vii) growth rate on an agar containing 0.1% pentachloronitrobenzene, (viii) production of extracellular tricaproinase, and (ix) fasciculation on a medium containing 10 ppm botran (2,6-dichloro-4-nitroanilin). The pattern of extracellular metabolites after thin-layer chromatography was used as a chemotaxonomic criterion. The species investigated, the number of isolates investigated, and the toxins which some of these isolates produce were: Penicillium roqueforti (18) (patulin), P. citrinum (11) (citrinin), P. patulum (9) (patulin and griseofulvin), P. expansum (patulin and citrinin), P. hirsutum (13), P. brevicompactum (19), and P. chrysogenum (12). Widespread species of the P. cyclopium, P. viridicatum, and P. expansum series of Raper and Thom (A Manual of the Penicillia, 1949) were subdivided into four new groups: “P. crustosum pA” (29) (penitrem A), “P. melanochlorum” (29), “P. cyclopium p” (119) (penicillic acid and infrequently penitrem A), and “P. viridicatum o-c” (43) (ochratoxin A and citrinin). “P. viridicatum o-c” was separated from “P. cyclopium p” due to its ability to grow on nitrite as sole nitrogen source. The species and groups investigated were related to the new taxonomic classification of the genus Penicillium according to Pitt.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

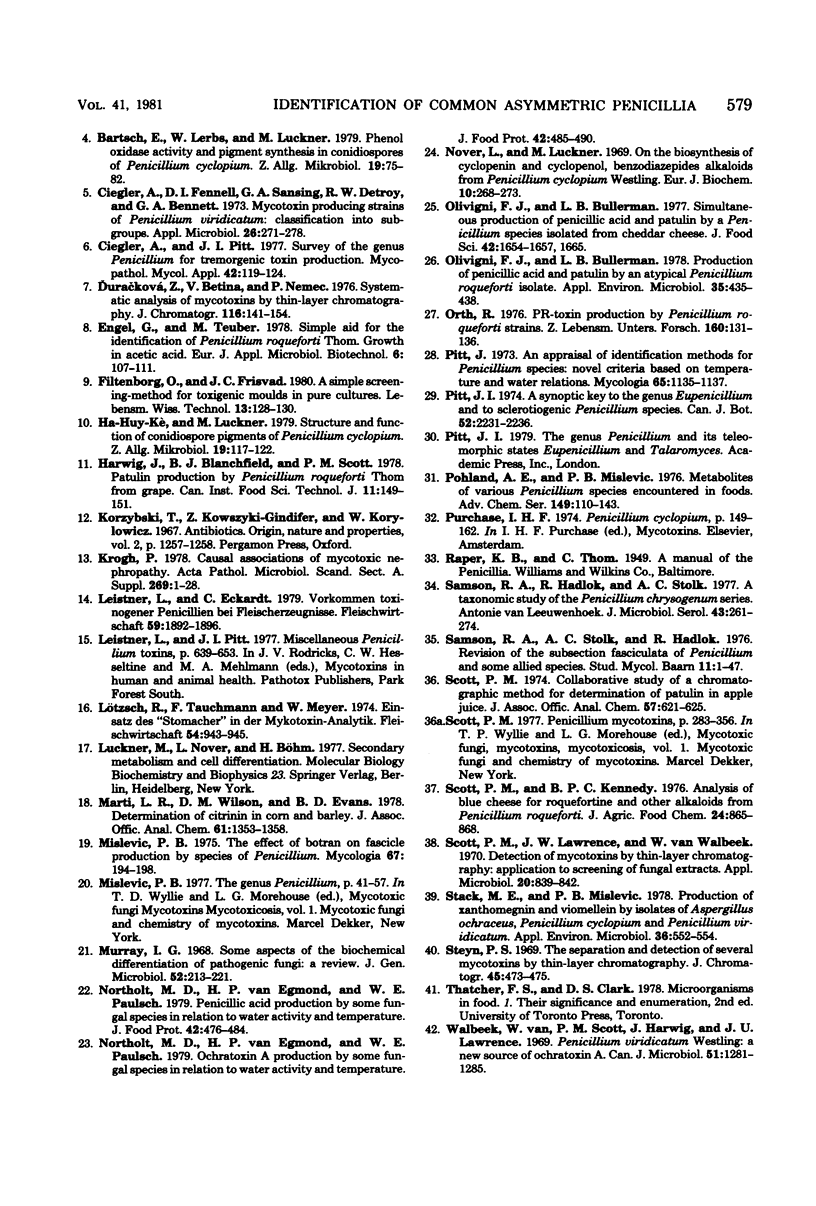

- Ba D., Jemmali M., Drapron R. Activité lipolytique et production d'aflatoxines chez Aspergillus flavus. Ann Microbiol (Paris) 1977 Jul;128B(1):87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J. M., Austwick P. K., Carter R. L., Flynn F. V., Peristianis G. C., Aldridge W. N. Balkan (endemic) nephropathy and a toxin-producing strain of Penicillium verrucosum var cyclopium: An experimental model in rats. Lancet. 1977 Mar 26;1(8013):671–675. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(77)92115-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch E., Lerbs W., Luckner M. Phenol oxidase activity and pigment synthesis in conidiospores of Penicillium cyclopium. Z Allg Mikrobiol. 1979;19(2):75–82. doi: 10.1002/jobm.3630190202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciegler A., Fennell D. I., Sansing G. A., Detroy R. W., Bennett G. A. Mycotoxin-producing strains of Penicillium viridicatum: classification into subgroups. Appl Microbiol. 1973 Sep;26(3):271–278. doi: 10.1128/am.26.3.271-278.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciegler A., Pitt J. I. Survey of the genus Penicillium for tremorgenic toxin production. Mycopathol Mycol Appl. 1970 Dec 28;42(1):119–124. doi: 10.1007/BF02051832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duracková Z., Betina V., Nemec P. Systematic analysis of mycotoxins by thin-layer chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1976 Jan 7;116(1):141–154. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)83709-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha-Huy-Kê, Luckner M. Structure and function of the conidiospore pigments of Penicillium cyclopium. Z Allg Mikrobiol. 1979;19(2):117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti L. R., Wilson D. M., Evans B. D. Determination of citrinin in corn and barley. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1978 Nov;61(6):1353–1358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mislivec P. B. The effect of Botran on fascicle production by species of Penicillium. Mycologia. 1975 Jan-Feb;67(1):194–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nover L., Luckner M. On the biosynthesis of cyclopenin and cyclopenol, benzodiazepine alkaloids from Penicillium cyclopium Westling. Eur J Biochem. 1969 Sep;10(2):268–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1969.tb00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivigni F. J., Bullerman L. B. Production of penicillic acid and patulin by an atypical Penicillium roqueforti isolate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978 Feb;35(2):435–438. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.2.435-438.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth R. PR-Toxinbildung bei Penicillium roqueforti-Stämmen. Z Lebensm Unters Forsch. 1976 Feb 27;160(2):131–136. doi: 10.1007/BF01259958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt J. I. An appraisal of identification methods for Penicillium species: novel taxonomic criteria based on temperature and water relations. Mycologia. 1973 Sep-Oct;65(5):1135–1157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott P. M., Kennedy P. C. Analysis of blue cheese for roquefortine and other alkaloids from Penicillium roqueforti. J Agric Food Chem. 1976 Jul-Aug;24(4):865–868. doi: 10.1021/jf60206a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott P. M., Lawrence J. W., van Walbeek W. Detection of mycotoxins by thin-layer chromatography: application to screening of fungal extracts. Appl Microbiol. 1970 Nov;20(5):839–842. doi: 10.1128/am.20.5.839-842.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack M. E., Mislivec P. B. Production of xanthomegnin and viomellein by isolates of Aspergillus ochraceus, Penicillium cyclopium, and Penicillium viridicatum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978 Oct;36(4):552–554. doi: 10.1128/aem.36.4.552-554.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steyn P. S. The separation and detection of several mycotoxins by thin-layer chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1969 Dec 23;45(3):473–475. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)86247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Walbeek W., Scott P. M., Harwig J., Lawrence J. W. Penicillium viridicatum Westling: a new source of ochratoxin A. Can J Microbiol. 1969 Nov;15(11):1281–1285. doi: 10.1139/m69-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]