Abstract

Absorption of a photon by an opsin pigment causes isomerization of the chromophore from 11-cis-retinaldehyde to all-trans-retinaldehyde. Regeneration of visual chromophore following light exposure is dependent on an enzyme pathway called the retinoid or visual cycle. Our understanding of this pathway has been greatly facilitated by the identification of disease-causing mutations in the genes coding for visual cycle enzymes. Defects in nearly every step of this pathway are responsible for human-inherited retinal dystrophies. These retinal dystrophies can be divided into two etiologic groups. One involves the impaired synthesis of visual chromophore. The second involves accumulation of cytotoxic products derived from all-trans-retinaldehyde. Gene therapy has been successfully used in animal models of these diseases to rescue the function of enzymes involved in chromophore regeneration, restoring vision. Dystrophies resulting from impaired chromophore synthesis can also be treated by supplementation with a chromophore analog. Dystrophies resulting from the accumulation of toxic pigments can be treated pharmacologically by inhibiting the visual cycle, or limiting the supply of vitamin A to the eyes. Recent progress in both areas provides hope that multiple inherited retinal diseases will soon be treated by pharmaceutical intervention.

Keywords: photoreceptors, vertebrate/metabolism, retinol (vitamin A), retinoid (visual) cycle, retina, Leber congenital amaurosis/therapy, macular degeneration/drug therapy

BACKGROUND AND SCOPE

The vertebrate retina contains two types of photosensitive cells, rods and cones. Both cell types are polarized and contain a nonmotile cilium connected to an outer segment (OS), which comprises a stack of membranous discs. The light-receptive proteins in these cells are the opsins, which are members of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family. The chromophore for most opsins is 11-cis-retinaldehyde (11-cis-RAL), which is covalently coupled to a lysine residue via a Schiff-base linkage (11-cis-retinylidene) (1). Absorption of a photon by a rhodopsin or cone-opsin pigment causes isomerization of 11-cis-RAL to all-trans-retinaldehyde (all-trans-RAL). This isomerization induces a sequence of short-lived changes in opsin conformation until reaching the activated state, metarhodopsin II (MII) (2). MII stimulates transducin, the α-subunit of a heterotrimeric G protein, as the first event in visual transduction (3). Stimulation of the transduction cascade results in closure of cGMP-gated cation channels in the plasma membrane of the OS and hyperpolarization of the photoreceptor cell. After a brief period of activation, MII is inactivated via phosphorylation and binding to arrestin, and subsequently decays to yield apo-opsin and free all-trans-RAL. To maintain continuous vision, vertebrates have evolved an enzymatic pathway that regenerates 11-cis-RAL (structure shown in Figure 1a) from all-trans-RAL to reform visual pigment. This pathway, called the visual cycle or retinoid cycle, takes place mainly in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), a single layer of cells adjacent to the photoreceptors (Figure 2). Important differences exist between rods and cones with respect to photoreception, phototransduction, and chromophore regeneration. These differences permit vision over a range of background light intensities spanning nine logs.

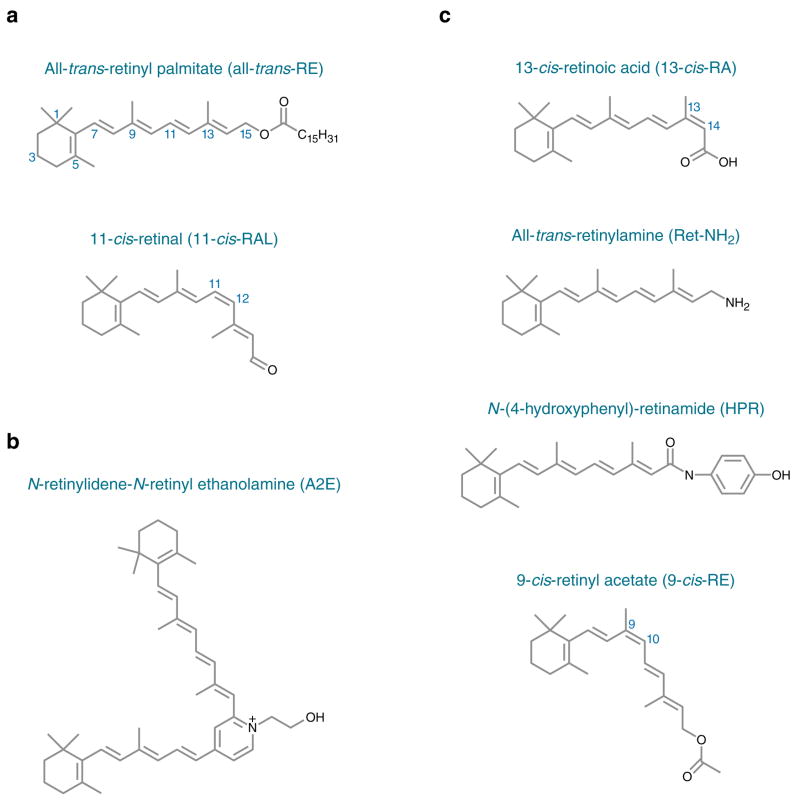

Figure 1.

Structures of visual retinoids (a), N-retinylidene-N-retinyl ethanolamine (A2E) (b), and inhibitors of A2E biogenesis (c).

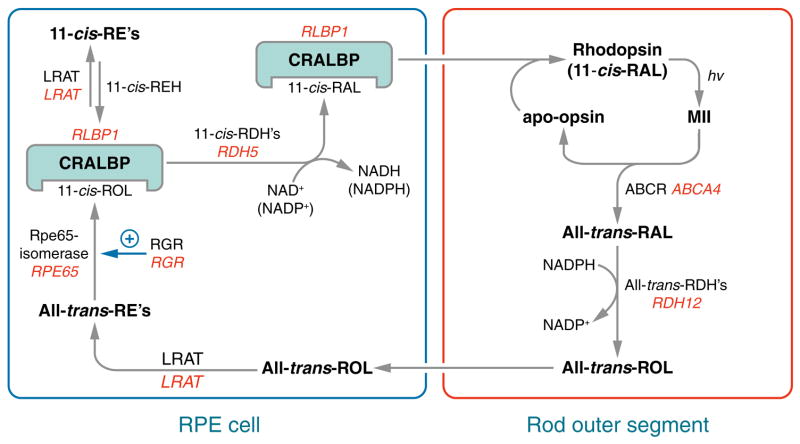

Figure 2.

Visual cycle in retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells. Absorption of a photon (hv) by a rhodopsin pigment molecule induces isomerization of 11-cis-RAL to all-trans-RAL resulting in activated metarhodopsin II (MII). Decay of MII yields apo-opsin and free all-trans-RAL. Translocation of all-trans-RAL from the disc membrane to the cytoplasmic space is facilitated by an ATP-binding cassette transporter called ABCR or ABCA4. Mutations in the human ABCA4 gene cause recessive Stargardt macular degeneration. The all-trans-RAL is reduced to all-trans-retinol (all-trans-ROL) by two or more all-trans-ROL dehydrogenases (all-trans-RDHs). Mutations in the gene for one (RDH12) cause Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) (85). The all-trans-ROL is released by photoreceptors and taken up by RPE cells where it is esterified to a fatty acid by lecithin:retinol acyl transferase (LRAT). Mutations in the LRAT gene cause a severe form of recessive retinitis pigmentosa (RP) (86). The isomerase, RPE-specific 65 kDa protein (Rpe65) uses an all-trans-retinyl ester as substrate to form 11-cis-retinol (11-cis-ROL) plus a free fatty acid. Mutations in the RPE65 gene also cause LCA (87, 88). The Rpe65 isomerase activity may be regulated by the non-photoreceptor opsin, RGR (131). Mutations in the RPE-retinal G protein-coupled receptor (RGR) gene also cause recessive RP (93). 11-cis-ROL binds to the cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein (CRALBP). Mutations in the gene for CRALBP (RLBP1) cause still another form of recessive RP (137). 11-cis-ROL may be esterified by LRAT to yield 11-cis-retinyl esters, a stable storage-form of pre-isomerized retinoid. 11-cis-retinyl esters are hydrolyzed to 11-cis-ROL for synthesis of chromophore by 11-cis-retinyl ester hydrolase (11-cis-REH), which has not yet been cloned. 11-cis-ROL is oxidized to 11-cis-RAL by several 11-cis-ROL dehydrogenases (11-cis-RDHs), including RDH5 and RDH11. Mutations in the gene coding for RDH5 cause delayed dark adaptation and a mild retinal dystrophy called fundus albipunctatus in humans (141). 11-cis-RAL is also bound to CRALBP before being released by the RPE and taken up by the photoreceptor where it recombines with opsin to form rhodopsin.

Ensuring an adequate supply of chromophore is critical for maintaining vision and preserving the health of photoreceptors. The genes for many enzymes and retinoid-binding proteins of the visual cycle have been implicated in recessively inherited blinding diseases such as Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), Stargardt macular degeneration, congenital cone-rod dystrophy, and retinitis pigmentosa (RP). The severity and high penetrance of these diseases underscores the essential nature of the retinoid cycle for maintaining a functional visual system. The phenotypes of these diseases have been successfully replicated in experimental animals with engineered or spontaneous mutations in retinoid cycle genes. These animal models have provided insight into the etiology of the different diseases and served as a starting point in the development of therapies.

THE RETINOID (VISUAL) CYCLE

Transport of all-trans-RAL from OS Discs

Following inactivation of MII, all-trans-RAL dissociates from the opsin protein into the bilayer of OS disc membranes. In vitro, all-trans-RAL partitions rapidly between phospholipid vesicles in aqueous media (4, 5); hence, disc membranes are not a barrier to its diffusion. Retinal also readily condenses with phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) to form the imine, N-retinylidene-PE (N-ret-PE). Although this reaction is reversible, clearance of all-trans-RAL from the interior of discs is delayed by the formation of N-ret-PE on the inner leaflet of disc membranes. A retina-specific ATP-binding cassette transporter called ABCR (also known as ABCA4) has been described in the discs of rod and cone OS (6–8). Mice with a knockout mutation in the abcr gene show delayed clearance of all-trans-RAL and elevated N-ret-PE in the retina following exposure to light (9, 10). In vitro biochemical studies suggest that ABCR is an outwardly directed flippase for N-ret-PE (11, 12), consistent with the phenotype in abcr−/−mice (9, 10). Thus, ABCR appears to facilitate the transfer of all-trans-RAL from disc membranes to the cytoplasmic space for subsequent reduction to all-trans-retinol (all-trans-ROL).

Reduction of all-trans-RAL to all-trans-ROL

The first catalytic step in the visual cycle involves enzymatic reduction of all-trans-RAL to all-trans-ROL (vitamin A) by retinol dehydrogenases (RDHs) (Figure 2). This reaction is carried out in rods and cones by members of the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family. Several SDRs that catalyze reduction of all-trans-RAL in vitro using NADPH as a cofactor have been identified in photoreceptors (13–15). Mice with a knockout mutation in the gene for photoreceptor RDH (prRDH, RDH8) exhibited a several-fold slower clearance of all-trans-RAL from retinas following a bright flash (16). However, the kinetics of rhodopsin regeneration in these mice were indistinguishable from wild-type (WT) mice. These observations suggest that mouse photoreceptors contain at least one additional, functionally significant all-trans-ROL dehydrogenase besides RDH8.

Transfer of all-trans-ROL from Photoreceptor to RPE Cell

Newly formed all-trans-ROL is rapidly released by photoreceptor cells to the extracellular space, also called the interphotoreceptor matrix (IPM). Interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (IRBP) is a 140-kDa glycoprotein secreted by photoreceptors and present at micromolar concentrations in the IPM (17–19). IRBP contains binding sites for both 11-cis- and all-trans-retinoids (20). The endogenous retinoid ligands for IRBP include all-trans-ROL, 11-cis-RAL, and 11-cis-retinol (11-cis-ROL) (21, 22). In vitro, IRBP has been shown to accelerate the removal of all-trans-ROL from bleached photoreceptors (23). Retinoids bound to IRBP are protected from both oxidation and isomerization (24, 25). Within RPE cells, cellular retinol-binding protein-1 (CRBP1) binds all-trans-ROL with a 100-fold higher affinity than does IRBP (26, 27). CRBP1 thus promotes the uptake of all-trans-ROL into the RPE. RPE cells may also take up all-trans-ROL by endocytosis of holo-IRBP (28) and by phagocytosis of shed OS (29). Finally, all-trans-ROL is taken up from blood in the choroidal circulation through the basal membranes of RPE cells.

Esterification of All-trans-ROL in RPE Cells

The major retinyl ester synthase in RPE cells is lecithin:retinol acyl transferase (LRAT), which catalyzes the transfer of a fatty acyl group from phosphatidylcholine to all-trans-ROL (30, 31) (Figure 2). LRAT preferentially uses all-trans-ROL bound to CRBP1 as substrate (32). Consistently, mice with a knockout mutation in the crbp1 gene have increased all-trans-ROL and reduced all-trans-retinyl esters in the RPE (33). A second retinyl ester synthase activity called acyl-CoA:retinol acyltransferase (ARAT) has been identified in RPE (30, 34) and cone-dominant chicken and ground-squirrel retinas (35, 36). In contrast to LRAT, ARAT uses an activated fatty acid such as palmitoyl coenzyme A (palm CoA) as an acyl donor to all-trans-ROL. ARAT has not been purified or cloned. However, acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase type-1 (DGAT1), which catalyzes palm CoA-dependent synthesis of triglycerides from diacylglycerol, was recently shown also to catalyze palm CoA-dependent synthesis of all-trans-retinyl esters from all-trans-ROL (37–39), and thus may contribute to ARAT activity in some tissues. Mice with a knockout mutation in the lrat gene contain only trace retinyl esters in ocular tissues (40). The virtual absence of retinyl esters despite the presumed presence of ARAT in lrat−/− eyes may be due to the approximately tenfold-higher KM of ARAT for all-trans-ROL (34). Both retinyl ester synthases are strongly inhibited by apo-CRBP1 (36). Interestingly, lrat−/− mice have higher than normal levels of retinyl esters in adipose tissue (39), which is likely due to ARAT activity. All-trans-retinyl esters represent a stable storage form of vitamin A that is non-cytotoxic and resistant to oxidation and thermal isomerization. These properties are due to the very low water-solubility of retinyl esters. The all-trans-retinyl esters are stored within internal membranes, and as oil-droplet structures associated with adipose differentiation-related protein in RPE cells (41).

Synthesis of 11-cis-ROL

The isomerase in RPE cells catalyzes the energetically unfavorable conversion of a planar all-trans-retinoid to the sterically constrained 11-cis configuration (Figure 2). The isomerase uses all-trans-retinyl esters as substrate (42–44). The abundant protein, RPE-specific 65-kDa protein (Rpe65), was recently identified as the isomerase in RPE cells (45–47). Consistently, mice with a knockout mutation in the rpe65 gene contain high levels of all-trans-retinyl esters in ocular tissues and no detectable 11-cis-retinoids (48). Rpe65 bears sequence similarity to β-carotene oxygenases found in mammals, insects, and plants (49), and to apocarotene oxygenase (ACO) in cyanobacteria (50). X-ray diffraction analysis showed that ACO has a seven-bladed β-propeller structure, with an Fe2+-4-His sphere at its axis (50). The four His residues that define the Fe2+-binding site are conserved in all members of the carotenoid cleavage enzyme family including Rpe65 (50). Rpe65 was shown to bind Fe2+, which is required for its catalytic activity (51). Rpe65 was also reported to be reversibly palmitoylated at three Cys residues, which may modulate its association with membranes (52).

The isomerization reaction is inhibited by its product, 11-cis-ROL (53, 54). This inhibition is relieved by the specific binding of 11-cis-ROL to cellular retinal-binding protein (CRALBP) in RPE cells (55, 56). CRALBP also binds 11-cis-RAL (56). A newly synthesized molecule of 11-cis-ROL has two potential fates. As discussed below, it can be oxidized to 11-cis-RAL for use as visual chromophore. Alternatively, it can be esterified by LRAT to form an 11-cis-retinyl ester (57). 11-cis-retinyl esters represent a storage form of pre-isomerized chromophore precursor. Hydrolysis of 11-cis-retinyl esters is catalyzed by 11-cis-retinyl ester hydrolase (11-cis-REH) in the plasma membrane of RPE cells (58, 59). 11-cis-REH is activated by apo-CRALBP (60), suggesting a regulatory mechanism to match the production of 11-cis-ROL with demand.

Oxidation of 11-cis-ROL to 11-cis-RAL

The final catalytic step in the visual cycle is oxidation of 11-cis-ROL to 11-cis-RAL (Figure 2). The first enzyme shown to catalyze this reaction in RPE cells is 11-cis-ROL dehydrogenase type 5 (RDH5) (61). Mice with a knockout mutation in the rdh5 gene show accumulation of 11-cis-ROL and 11-cis-retinyl esters in the RPE, and delayed recovery of rod sensitivity following exposure to bright light (62). Synthesis of 11-cis-RAL in rdh5−/− mice indicates the presence of at least one additional 11-cis-RDH activity in RPE. RDH11 is another SDR in RPE cells that oxidizes 11-cis-ROL to 11-cis-RAL (15). RDH11 may act in concert with RDH5 to generate visual chromophore. Double-knockout mice with disruptions in both the rdh5 and rdh11 genes still synthesize 11-cis-RAL, albeit more slowly than rdh5−/− or rdh11−/−single-knockout mice (63). This observation indicates the presence of at least one additional 11-cis-RDH activity in the RPE. The mechanism of 11-cis-RAL release from RPE cells into the IPM is not well understood. 11-cis-RAL is bound to CRALBP in RPE cells (56). CRALBP binds to ezrin-radixin-moesin (ERM)-binding phosphoprotein 50 (EBP50), a PDZ-domain protein associated with the cytoskeleton adjacent to the plasma membrane of RPE and Muller cells (64, 65). This interaction may target 11-cis-RAL to the apical plasma membrane for release into the IPM. IRBP binds 11-cis-RAL at higher affinity than it binds all-trans-ROL (66). Both in vitro and in cell culture, IRBP has been shown to remove 11-cis-RAL efficiently from RPE membranes (67, 68). Given the seeming importance of IRBP in the bidirectional flow of retinoids between photoreceptors and RPE, it is surprising that mice with a knockout mutation in the irbp gene exhibit only slight slowing of rhodopsin regeneration after a bright flash (69, 70). This retinoid transport may be due to the presence of other retinoid-binding proteins in the IPM such as retinol-binding protein (RBP) (19).

Regeneration of Visual Pigments

Although qualitatively similar, rods and cones differ greatly in sensitivity, dynamic range, and speed of the photoresponse. For example, rods detect single photons (71) and show response saturation at 500 photoisomerizations per second (72). Cones, on the other hand, are 100-fold less sensitive than rods (73) but can still respond to light flashes at levels of background illumination that produce 106 photoisomerizations per second (74). Also, the response of cones is several-fold faster than rods (75). These differences reflect intrinsic properties of the rod and cone visual pigments. Rhodopsin is exceedingly quiet, with a spontaneous activation rate of one thermal isomerization per 2000 years (76). Cone opsins are much noisier than rhodopsin for two reasons. First, the spontaneous isomerization rate of red-cone opsin is 10,000-fold higher than that of rhodopsin (77). Second, 11-cis-RAL spontaneously dissociates from cone-opsin. A dark-adapted red cone contains approximately 10% apo-cone-opsin due to spontaneous dissociation of chromophore (78). In contrast, 11-cis-RAL combines irreversibly with opsin in rods. Chromophore-free (apo-) opsin weakly activates transducin (79). These effects contribute to partial activation of the transduction cascade in cones independent of light. This “dark noise” is responsible for the reduced sensitivity and faster photoresponse observed in cones.

ALTERNATE PATHWAY FOR REGENERATING VISUAL CHROMOPHORE IN CONES

Rods require 11-cis-RAL from the RPE to regenerate rhodopsin pigment. Cones, however, are not dependent on the RPE (80, 81) and can use both 11-cis-RAL and 11-cis-ROL to regenerate cone-opsin pigments (82). An NADP+/NADPH-dependent 11-cis-RDH activity has been identified in cones, but not rods, which may explain the capacity of cones to utilize 11-cis-ROL as a chromophore precursor (35). Cone-dominant ground-squirrel and chicken retinas contain a retinoid isomerase activity distinct from Rpe65 that converts all-trans-ROL directly to 11-cis-ROL without formation of an all-trans-retinyl ester intermediate (35, 36). This isomerization reaction appears to be driven by secondary esterification of the 11-cis-ROL product (35, 36). The ester synthase in cone-dominant retinas uses palm CoA as an acyl donor, and therefore is a type of ARAT (35, 36). Cultured Muller cells take up all-trans-ROL and release 11-cis-ROL (83), suggesting that the retinol isomerase and coupled palm CoA-dependent ester synthase are located in Muller cells. These activities, plus the 11-cis-RDH in cones, appear to define catalytic steps of an alternate visual cycle in cone-dominant retinas (Figure 3). This proposed pathway may permit cones to escape competition from rods for visual chromophore under conditions of bright light. Confirmation of this pathway awaits molecular cloning of the enzymes for these three catalytic activities.

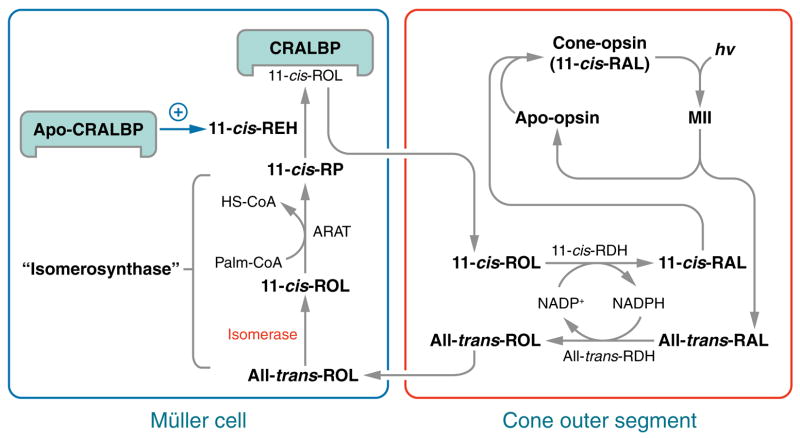

Figure 3.

Hypothesized alternate visual cycle for regeneration of cone pigments. Absorption of a photon (hv) induces 11-cis to all-trans isomerization of the retinaldehyde chromophore in a cone opsin pigment. After dissociation from apo-cone-opsin, the resulting all-trans-RAL is reduced to all-trans-ROL by the NADP+/NADPH-dependent all-trans-ROL dehydrogenase (all-trans-RDH) and released from the photoreceptor outer segment (OS), where it is bound to interstitial retinol binding protein (IRBP) (not shown). The all-trans-ROL released by rods and cones is taken up by Muller cells where it is isomerized to 11- cis-ROL by an isomerase, and esterified to form an 11-cis-retinyl ester by acyl-CoA:retinol acyltransferase (ARAT). These enzyme activities are kinetically coupled and named “isomerosynthase” (35, 36). An 11-cis-retinyl ester is hydrolyzed by 11-cis-retinyl ester hydrolase (REH) to yield 11-cis-ROL, which binds to cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein (CRALBP). 11-cis-REH is regulated by the ratio of apo- to holo-CRALBP in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells (60). A similar regulatory mechanism is suggested here in Muller cells. 11- cis-ROL released by the Muller cell is bound to IRBP (not shown) and taken up by the cone outer-segment, which contains an NADP+/NADPH-dependent 11-cis-ROL dehydrogenase (11-cis-RDH) activity (35). This activity oxidizes 11-cis-ROL to 11-cis-RAL, which combines with apo-cone-opsin to form a new cone visual pigment. The presence of reciprocal NADP+/NADPH-dependent all-trans-ROL and 11-cis-RDHs in cones affords a self-renewing supply of dinucleotide cofactor at all rates of photoisomerization.

EYE DISEASES ASSOCIATED WITH DEFECTIVE METABOLISM OF VISUAL RETINOIDS

Vision in vertebrates is dependent on a sustained supply of 11-cis-RAL chromophore. Accordingly, mutations in the genes for retinoid cycle proteins frequently cause impaired vision (Table 1). Most of these diseases are recessively inherited due to loss of the catalytic or retinoid-binding function. In contrast, diseases caused by mutations affecting structural or signaling proteins typically exhibit dominant inheritance (84). The phenotypic severity of retinoid cycle mutations is strongly influenced by the degree of functional redundancy at each step in the pathway. For example, the RPE contains multiple enzymes that catalyze oxidation of 11-cis-ROL to 11-cis-RAL (63), but only one enzyme (Rpe65) that catalyzes isomerization of all-trans-retinyl esters to 11-cis-ROL. Accordingly, mutations in RDH5 cause only a mild clinical phenotype, whereas mutations in RPE65 cause the severe blinding disease, LCA. Mutations in the RDH12 and LRAT genes also cause LCA (85–88). This phenomenon of phenotypic convergence is called nonallelic heterogeneity. In contrast, mutations in the same gene may produce a variety of clinical phenotypes. For example, different mutations in ABCR can cause Stargardt macular degeneration (6), cone-rod dystrophy (89), or recessive RP (90, 91). Also, heterozygous mutations in ABCR increase the risk of developing age-related macular degeneration (92). This phenomenon of phenotypic divergence is called allelic heterogeneity.

Table 1.

Human eye diseases associated with defective metabolism of visual retinoids

| Traditional name | Gene name and locus | Biochemical properties | Gene defects associated with eye diseases; inheritance | Phenotype | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCR, rim membrane protein (RMP), Stargardt disease protein (STGD1), ABC10, CORD3, RP19 | Retinal-specific ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABCR) member 4; ABCA4; 1p22.1-p21 | Multi-spanning membrane-bound protein found along the rim of disc in rods and cones, possess preferable activity toward N-retinylidene-phosphatidylethanolamine (N-ret-PE) removing all-trans-RAL from intradiscal space | 1. Stargardt disease (STGD), also known as fundus flavimaculatus (FFM); recessive | Juvenile- and late-age-onset macular dystrophy, alterations of the peripheral retina, and subretinal deposition of lipofuscin-like material | (6) |

| 2. Risk factor in age-related macular degeneration (controversial) | Age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) is a degenerative condition of the macula (the central retina). Age-related macular degeneration occurs in two forms: wet (occurs when abnormal blood vessels behind the retina start to grow under the macula) and dry (when cones of the macula degenerate) | (217) | |||

| 3. Autosomal recessive cone-rod dystrophy | A progressive retinal degenerative disease that causes deterioration of the cones and rods in the retina, eventually leading to blindness | (218) | |||

| 4. Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa (RP) | RP refers to a group of inherited disorders that slowly lead to blindness owing to abnormalities of primarily the rods followed by cone death | (90, 219) | |||

|

| |||||

| RDH12, LCA3 gene | Retinol dehydrogenase (RDH) 12 (all-trans and 9-cis); RDH12; 14q24.1 | RDH12 is a microsomal short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase, expressed preferentially in the retina, that catalyzes the redox reaction with high preference toward NADP (NADPH), but displays dual-specificity toward both all-trans-and cis-ROLs. | Autosomal recessive childhood-onset severe retinal dystrophy | Severe, progressive rod-cone dystrophy with severe macular atrophy but no or mild hyperopia (farsightedness) | (116) |

|

| |||||

| LRAT; lecithin:retinol acyltransferase | Lecithin: retinol acyltransferase; LRAT; 4q32.1 | Single helix-anchorage membrane-bound ubiquitously expressed phosphatidylcholine–retinol O-acyltransferase with highest levels in the liver and RPE | Autosomal recessive early-onset severe retinal dystrophy (symptoms similar to or identical with Leber’s Congenital Amaurosis, congenital retinal blindness, hereditary epithelial aplasia, and retinal aplasia) | Congenital or early severe and progressive rod-cone dystrophy with progressive retinal atrophy, although in some cases vision can remain stable through young adult life, searching or pendular nystagmus—an involuntary, rhythmical, repeated movement of the eyes, photophobia, sluggish pupillary responses; the electroretinographic (ERG) response is characteristically “nondetectable” or severely subnormal; characteristic poking, rubbing, and/or pressing of the eyes (oculo-digital signs). Fundus may have a normal appearance in infancy and progressively pigmented later in life | (86) |

| Rpe65, Retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)-specific protein 65 kDa, LCA2, RP20; membrane-bound Rpe65 | RPE-specific protein 65 kDa; Rpe65; 1p31 | Membrane associated, RPE specific 65 kDa proteins, Rpe65 possesses Fe2+-dependent isomerization activity of all-trans-retinyl esters to 11-cis-ROL. Based on the sequence, Rpe65 belongs to carotenoid oxygenases. Rpe65 binds retinoids with a high affinity | Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), recessive | Progressive visual loss, infant born blind or with highly attenuated vision, lose vision within a few months after birth, early-onset severe rod-cone dystrophy, in infants blindness in dark settings and light perception at bright light, attenuated retinal vessels and a variable amount of retinal pigmentation in older patients and a reduced or nondetectable electroretinogram at all ages | (88) |

| Autosomal recessive RP | Photoreceptor degeneration with good central vision within the first decade of life, attenuated retinal vessels and a variable amount of retinal pigmentation in older patients, and a reduced or nondetectable electroretinogram at all ages | (220) | |||

|

| |||||

| RGR, Retinal G protein– coupled receptor; RPE retinal G protein– coupled receptor | Retinal G protein–coupled receptor; RGR; 10q23 | RGR belongs to a superfamily of G protein–coupled receptors (heptahelical transmembrane receptor) is an invertebrate rhodopsin homologue found exclusively in the RPE and Muller cells. Possible proposed roles are as a retinal photoisomerase or in GPCR signaling in yet unidentified pathway | Autosomal dominant and recessive RP | Severely constricted visual fields, attenuated retinal vessels, diffuse depigmentation of the RPE, and intraretinal pigment deposits in the periphery. The depigmented patches involved the central macula associated with severely decreased acuity | (93) |

|

| |||||

| CRALBP, Cellular retinal-binding protein | Retinaldehyde binding protein 1, RLBP1; 15q26 | Abundant, soluble protein of the (RPE) and retinal Muller cells, where it binds 11-cis-ROL and 11-cis-RAL | Autosomal recessive retinitis punctata albescens, autosomal recessive RP Bothnia type | Bothnia dystrophy is a retinal dystrophy with striking similarity to the rod-cone dystrophies and has a high prevalence in northern Sweden. Retinitis punctata albescens is clinically similar to RP and results in progressive visual field loss, night-blindness, and retinal vascular attenuation | (136, 137) |

|

| |||||

| RDH5; 11-cis-ROL dehydrogenase. | Retinol dehydrogenase (RDH) 5 (11-cis and 9-cis); RDH5; 12q13-q14 | RDH5 is a microsomal short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase, ubiquitously expressed with a high expression in the RPE. The enzyme catalyzes the redox reaction with the highest preference toward NAD (NADH), and 11-cis- and 9-cis-ROL | Autosomal recessive fundus albipunctatus | This form of fleck retinal disease is characterized by discrete uniform white dots over the entire fundus with greatest density in the midperiphery and no macular involvement. Night blindness (delay dark adaptation) occurs with or without cone dystrophy. Rod and cone resensitization was extremely delayed following full bleaches; the rate of cone recovery was slower than rods | (141) |

A powerful approach to understanding the etiologies of retinoid cycle diseases has been the creation and characterization of animal models (Table 2). These animal models are also useful for developing genetic and pharmacologic treatments. However, phenotypic differences exist between animals and humans carrying mutations in the same gene. For example, loss-of-function mutations in the human RPE retinal G protein–coupled receptor (RGR) gene cause RP leading to photoreceptor degeneration and blindness (93), whereas rgr−/− knockout mice show no signs of photoreceptor degeneration (94, 95). A similar situation exists with recessive Stargardt macular degeneration, which causes visual loss in children (96), and abcr−/− knockout mice, where photoreceptors degenerate only very slowly (97). These apparent differences in phenotypic severity may reflect the much longer lifespan of humans. At the optical center of the human retina is a structure called the macula, which contains a very high density of photoreceptors. Rods and cones within the macula are unusually vulnerable to cell death in a group of blinding diseases called the macular degenerations. Photoreceptors of the peripheral retina are affected late in the course of several macular degenerations. The retinas of most non-primate animals, including mice, do not contain a macula. The entire retina of these animals histologically resembles the peripheral retina of humans. The absence of a central macula is another explanation for the milder phenotypes in animals with mutations in retinoid cycle genes. Despite these differences, animal models with engineered mutations in visual cycle genes are valuable for studying the function of the encoded protein and for developing new treatments.

Table 2.

Animal models of human eye diseases associated with defective metabolism of visual retinoids

| Gene Name | Animal Model | Phenotype | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retinal-specific ATP-binding cassette transporter member 4 (ABCA4) | abcr−/− mice | The two lines of abcr−/− mice exhibit accumulation of high levels of lipofuscin within the RPE cells; increased levels of retinal in the outer segment (OS) and delayed dark adaptation | (9, 210) |

|

| |||

| Lecithin: retinal acyltransferase (LRAT) | lrat−/− mice | The lrat−/− mice have no detectable levels of retinyl esters within the RPE and show severely attenuated rod and cone visual responses. Other tissues such as liver, kidney, and lung have trace levels of retinyl esters, but there are increased levels of retinyl esters in adipose tissue. A second line of lrat−/− mice that have the Neo cassette removed following recombination show a similar phenotype | (39, 40, 221) |

|

| |||

| RPE-specific protein 65 kDa; Rpe65 | rpe65−/− mice | The rpe65−/− mice show severely attenuated rod and cone responses, progressive retinal degeneration owing to block in regeneration of 11-cis-RAL, consistent with the role of Rpe65 in the isomerization of all-trans-ROL. High levels of all-trans-retinyl esters accumulate in lipid vacuoles in the RPE of rpe65−/− mice | (88) |

| rd12 mice | The rd12 mice have a naturally occurring nonsense mutation in exon 3 of murine Rpe65. There are no detectable levels of 11-cis-RAL or rhodopsin and lipid droplets accumulate in the RPE. At 5 months of age, small white dots appear on the retinas of rd12 mice | (123) | |

| Swedish Briard/Briard Beagle dogs with naturally occurring mutation | A homozygous 4bp deletion in exon 5 of canine Rpe65 leads to a frameshift mutation and truncation of the resulting polypeptide. These dogs exhibit early onset, progressive retinal dystrophy and accumulation of lipid vacuoles in their RPE | (105, 106) | |

|

| |||

| Retinal G protein–coupled receptor; RG | rgr−/− mice | The rgr−/− mice have reduced levels of 11-cis-RAL and rhodopsin, and slightly reduced electroretinographic (ERG) responses. The rates of rhodopsin regeneration are similar to WT mice | (94, 95) |

|

| |||

| Retinal-binding protein 1, RLBP1 | rlbp1−/− mice | rlbp1−/− mice have delayed rates of rhodopsin regeneration and recovery of chromophore following a bleach and accumulation of retinyl esters | (140) |

|

| |||

| 11-cis-ROL dehydrogenase (RDH); RDH5 | rdh5−/− mice | The rdh5−/− mice exhibit accumulation of cis-retinyl esters in their RPE. In contrast to the human disease caused by mutations in RDH5, fundus albipunctatus, the rdh5−/− mice do not exhibit delayed dark adaptation or the formation of the characteristic white dots | (144) |

RP Caused by Mutations in the Gene for Rhodopsin

Mutations in the gene for rhodopsin are the most common cause of RP and lead to both autosomal dominant RP (ADRP) and autosomal recessive RP (ARRP). Mutant rhodopsin can cause disease through several different pathologic mechanisms, such as cellular toxicity owing to improperly folded or constitutively activated protein in ADRP, or impaired activation or reduced opsin level leading to ARRP. Mice with a knockout mutation in the rod opsin gene fail to form rod OS and have no rod electroretinographic (ERG) response, but show a cone response early in life (98). Cone photoreceptors disappear at three months of age. Heterozygous opsin+/− mice have 40% less rhodopsin and consequently a 40% reduction in 11-cis-RAL (99).

Supplementation with natural or synthetic retinoids may slow photoreceptor degeneration owing to opsin mutations (103). A naturally occurring mutation in dogs causing a Thr4Arg rhodopsin substitution leads to autosomal dominantly inherited retinal degeneration (104). The degeneration resembles that of the Thr4Lys rhodopsin substitution that affects some ADRP patients. Retinal degeneration in dogs with Thr4Arg-substituted rhodopsin is due to its constitutive activation. This mechanism was demonstrated by crossing dogs carrying Thr4Arg-substituted rhodopsin with Briard dogs with a null mutation in the gene for Rpe65 (105, 106). These double heterozygous-mutant dogs exhibited greatly accelerated degeneration (107). High levels of apo-opsin owing to loss of the Rpe65-isomerase, combined with the presence of Thr4Arg-substituted rhodopsin, caused severe overstimulation of the transduction cascade and rapid photoreceptor death. Retinoid supplementation may be a viable approach to slow photoreceptor degeneration in human diseases associated with critical apo-opsin accumulation, as discussed below.

Stargardt Macular Degeneration

Autosomal recessive Stargardt disease is the most common inherited maculopathy of the young, with an estimated prevalence of 1:10,000 (108). The first symptoms of Stargardt disease are blurred vision not correctable with glasses, and delayed dark adaptation. Later, Stargardt disease causes progressive loss of central vision with central blind spots and a diminished ability to perceive colors. Ultimately, the disease Funduscopic examination of the retina in Stargardt patients shows a macular lesion surrounded by irregular yellow-white flecks or spots, which give rise to the alternate name for this disease, fundus flavimaculatus. Histologically, Stargardt disease is characterized by the accumulation of fluorescent lipofuscin pigments in cells of the RPE, degeneration of the RPE, and death of photoreceptors (96, 110). Stargardt disease patients commonly show a “dark choroid” during fluorescein angiography due to this light-absorbing lipofuscin material in the RPE (111). Stargardt disease patients also show fundus autofluorescence by scanning laser ophthalmoscopy, again owing to these lipofuscin pigments (112). Stargardt disease is caused by mutations in the ABCR (ABCA4) gene (6). Approximately 400 alleles of ABCR have been identified in patients with inherited macular and retinal degenerations. ABCR is also highly polymorphic in the normal population. This heterogeneity presents a challenge to define disease-causing alleles. Biochemical analysis of postmortem samples from Stargardt disease patients showed elevated PE and N-ret-PE in the retina, and elevated lipofuscin fluorophores such as A2PE-H2 and A2E in the RPE (10).

The abcr−/− knockout mouse is an animal model for Stargardt disease and ABCR-mediated retinal degenerations (9). Several features of the Stargardt disease phenotype are present in these mice. For example, PE and N-ret-PE are elevated in abcr−/− retinas (9, 10). Clearance of all-trans-RAL from OS is delayed in abcr−/− mice following light exposure. Accumulated lipofuscin pigments are visible by electron microscopy in the RPE of abcr−/− mice. The lipofuscin fluorophores, A2E and A2PE-H2, are also dramatically elevated in RPE (9, 10). Physiologically, abcr−/− mice showed delayed recovery of rod sensitivity following light exposure (9), again similar to patients with Stargardt disease. Loss of ABCR activity causes increased N-ret-PE and all-trans-RAL in OS discs. This initial reaction favors secondary condensation of N-ret-PE with all-trans-RAL to yield A2PE-H2. A2PE-H2 in OS is probably not toxic to photoreceptors; however, the distal ~10% of photoreceptor OS are phagocytosed daily by the RPE as part of the normal disc-renewal process (29). A2PE-H2 is converted to A2E and A2E-epoxides upon exposure to short-wavelength light in the acidic and oxidizing conditions of RPE phagolysosomes (10, 113, 114).

LCA Due to Mutations in the Gene for all-trans-RDH

All-trans-RAL is reduced to less-toxic all-trans-ROL by members of the short-chain alcohol dehydrogenases, including RDH8 and RDH12. Recently, mutations in RDH12 were shown to cause LCA (115, 116). No mutation in RDH8 has been associated with a retinal dystrophy in humans. Mice with a knockout mutation in the rdh8 gene show normal kinetics of rhodopsin regeneration and delayed recovery of sensitivity following exposure to bright light (16). An identical pattern is seen in abcr−/− mice (9). ABCR and all-trans-RDH act sequentially in the visual cycle to remove all-trans-RAL following a photobleach (Figure 2). Delayed dark adaptation in rdh8−/− and abcr−/− mice is probably due to noncovalent association of all-trans-RAL with opsin to form a “noisy” photoproduct that activates transducin (117).

Mutations in the LRAT Gene Cause Early LCA

Loss-of-function mutations in the LRAT gene have been reported in three individuals with LCA (86). These patients are otherwise healthy, suggesting that LRAT is not required for the uptake or storage of all-trans-ROL in extraocular tissues when the intake of dietary vitamin A is normal. The lrat−/− knockout mouse is an animal model for LRAT-mediated retinal dystrophy. These animals contain only trace retinoids in ocular tissues (40). Accordingly, vision is extremely impaired from birth. OS are shortened in lrat−/− mice, and photoreceptors degenerate very slowly.

Mutations in RPE65 Cause LCA and Severe Recessive RP

Mutations in the gene for Rpe65 account for a significant percentage (11.4%) of early-onset retinal degenerations in humans (118). Numerous loss-of-function alleles in RPE65 have been described. Rod and cone function is absent or severely compromised at birth, as evidenced by extinguished or barely detectable responses by ERG.

The rpe65−/− mouse was the first animal model of a human disease caused by mutations in a retinoid cycle gene (48). These mice show massive accumulation of all-trans-retinyl esters and absent 11-cis-retinoids in ocular tissue, consistent with the role of Rpe65 as a retinoid isomerase (45–47). A lack of 11-cis-RAL chromophore leads to the virtual absence of rhodopsin and a nearly undetectable ERG response. Young rpe65−/− mice have a relatively normal retinal anatomy (48). The OSs of these mice contain a large amount of apo-opsin, which helps stabilize the structure of OS discs, in contrast to opsin−/− mice with severe OS disorganization (98). Age-dependent photoreceptor degeneration is seen in rpe65−/− mice, with the loss of cones preceding the loss of rods (119). This degeneration may be due to constitutive activation of the visual transduction cascade with a simultaneous reduction in intracellular Ca2+. In contrast to rhodopsin, which is “silent,” chromophore-free apo-opsin weakly activates transducin (120). This weak activation becomes significant in an OS populated largely or exclusively by apo-opsin (121). With prolonged dark-rearing, rpe65−/−mice gradually acquire light-sensitivity as assessed by ERG. This transient recovery of vision, which only survives one round of photoisomerization, is due to the formation of iso-rhodopsin (122). Iso-rhodopsin contains 9-cis-RAL chromophore instead of 11-cis-RAL. The origin of this 9-cis-RAL is unknown. It may represent a precursor of 9-cis-retinoic acid, a putative transcriptional regulatory molecule, which is trapped upon combination with apo-opsin.

Other animal models of RPE65-mediated retinal degenerations include the Swedish Briard dog (105, 106) and the rd12 mouse (123). Both spontaneous mutations result in premature truncation of the Rpe65 protein and cause severely reduced visual function. Interestingly, rd12 mice have small white dots throughout their retinas, similar to humans with fundus albipunctatus (123). The Briard dog and rd12 mouse phenotypes have been successfully rescued by gene therapy involving the viral-mediated transfer of a WT RPE65 gene to RPE cells (124–126).

Dominant and Recessive RP Due to Mutations in the RGR Gene

RGR is a non-photoreceptor opsin in RPE and Muller cells (127, 128). The function of RGR is unknown. In the dark, RGR preferentially binds all-trans-RAL, which forms a Schiff base with a lysine residue in the seventh transmembrane helix, similar to rhodopsin (129). Light exposure induces photoconversion of this bound all-trans-RAL to 11-cis-RAL (129). This photoisomerization has led to the suggestion that RGR functions as a “reverse” photoisomerase to regenerate visual chromophore in light, similar to retinochrome in the squid (130). Evidence against this proposed function for RGR is the observation of similar ERGs and 11-cis-RAL levels in rpe65−/−single and rpe65−/−, rgr−/− double knockout mice (95). More recently, RGR was suggested to activate the isomerase in a light-independent fashion (131), although no direct effect of RGR on isomerase activity was shown. Frame-shift mutations in the human RGR gene are associated with ADRP (93). Homozygous and compound-heterozygous mutations in RGR additionally have been associated with ARRP in a consanguineous Spanish family (132). Dominant and recessive inheritance of a retinal disease phenotype with mutations in the same gene have also been described for opsin (133, 134) and ABCR (6, 92).

The rgr−/− knockout mouse represents an animal model of RGR-mediated ARRP. The phenotype in rgr−/− mice is mild (94). These mice show reduced 11-cis-RAL and rhodopsin levels in the retina following light exposure, and increased all-trans-and 13-cis-retinyl esters in the RPE (94, 95, 135). Slightly decreased ERG responses are also seen, commensurate with the decreased levels of rhodopsin. Further study is required to elucidate the function of RGR and to explain the phenotype in humans with RGR-mediated RP.

Retinitis Punctata Albescens Caused by Mutations in the RLBP1 Gene Coding for CRALBP

Mutations in RLBP1 are responsible for a form of recessive RP called retinitis punctata albescens, characterized by subretinal punctate white-yellow deposits found during funduscopic exams (136, 137). Clinically, retinitis punctata albescens caused by mutations in RLBP1 is associated with night blindness and progressively impaired visual acuity during childhood (138). Although the rod response is undetectable by routine ERG, it reverts to normal following prolonged dark adaptation (139). Reductions in cone function are seen in older patients owing to photoreceptor degeneration.

Mice with a knockout mutation in the rlbp1 gene synthesize 11-cis-RAL chromophore very slowly and show massively delayed recovery of rod sensitivity following light exposure (140), consistent with the clinical phenotype in humans. As discussed above, binding of 11-cis-ROL by CRALBP is required to avoid product-inhibition of the isomerase (53, 54). In the absence of CRALBP, synthesis of 11-cis-ROL, and hence 11-cis-RAL chromophore, is greatly slowed. Accumulation of all-trans-retinyl esters is also seen in rlbp1−/− mice due to reduced consumption of substrate by the isomerase (140). Contrary to humans with RLBP1 mutations, photoreceptor degeneration is not seen in the rlbp1−/− mice.

Fundus Albipunctatus Caused by Mutations in RDH5

Fundus albipunctatus is a mild and rare form of congenital stationary night-blindness with a characteristic appearance on funduscopic exam of white dots scattered throughout the retina. Visual acuity is normal in patients with fundus albipunctatus, and the condition is only mildly progressive. This phenotype suggests a slowing of chromophore synthesis with no photoreceptor degeneration. Fundus albipunctatus is a recessive disease caused by mutations in the RDH5 gene for an 11-cis-RDH in RPE cells (141, 142).

Mice with a knockout mutation in the rdh5 gene also have a mild phenotype. Dark adaptation is normal in rdh5−/− mice and white spots are not visible on the retinas (62, 143). Thus, RDH5 represents a minor contributor to total 11-cis-RDH activity in humans and mice. The most prominent feature of the rdh5−/− phenotype is the accumulation of 13-cis-retinyl esters in the RPE (62). This accumulation may be due to low activity of the remaining 11-cis-RDHs toward 13-cis-ROL, followed by esterification of this aberrant substrate into 13-cis-retinyl esters by LRAT. In humans, the white dots may represent local accumulations of 11- and 13-cis-retinyl esters (144).

THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES FOR DISEASES CAUSED BY DEFECTS IN THE VISUAL CYCLE

Three strategies to treat diseases caused by mutations in retinoid cycle genes have been explored. The first and conceptually simplest strategy is to replace the defective gene by viral gene therapy. RPE cells take up and express recombinant viruses at high efficiency, which represents an important advantage of this approach. The second strategy involves pharmacologic replacement of missing chromophore. This strategy may be applicable to diseases with a primary deficit in chromophore biosynthesis. Examples include LCA owing to mutations in the LRAT and RPE65 genes. The third strategy is to slow the synthesis of chromophore by inhibiting steps in the visual cycle or limiting availability of all-trans-ROL precursor. This strategy is applicable to diseases associated with accumulation of toxic lipofuscin fluorophores such as A2E. As discussed below, A2E accumulation is seen in multiple forms of retinal and macular degenerations.

Gene Therapy Approach

The major goal of gene therapy is to incorporate a functional gene into a target cell, restoring production of the affected protein. Considerable progress has been made in developing efficient viral delivery systems and overcoming problems with undesirable immune responses (for reviews see References 145, 146). Successful gene therapy is dependent on efficient transduction of the target cell and sustained expression of the recombinant virus at a sufficient level. Adeno-associated virus (AAV), a nonpathogenic parvovirus, has been the most successful vector owing to its ability to transduce a variety of non-dividing cell types. AAV vectors contain no viral coding regions and therefore have low cytotoxicity. AAV has been employed for gene delivery to muscle, brain, liver, lung, RPE, and neural retina. Disadvantages of AAV vectors include a small cargo size (<5 kb) and the immune reaction elicited by the viral capsid, which limits the number of possible recurrent treatments (147, 148). The immune-privileged status of the eye helps with this problem.

An initial study of viral gene-transfer into the eye was performed on transgenic mice and rats expressing Pro23His-substituted rhodopsin. Viral-mediated expression of ribozymes that targeted the transgene mRNA reduced expression of the mutant rhodopsin and slowed the rate of photoreceptor degeneration (149, 150). Following this initial success, gene therapy was employed for treating RPE65-mediated LCA in the Briard dog (105). These dogs suffer from early and severe visual impairment, similar to humans with LCA. AAV vectors carrying WT human or canine RPE65 were delivered subretinally to rpe65-mutant Briard dogs (124, 126, 151, 152). ERG measurements showed dramatic improvements in the light sensitivity of rods and cones. Immunohistochemical analysis showed expression of Rpe65 in RPE cells surrounding the site of subretinal injection. Retinoid analysis confirmed that rescue of Rpe65 expression leads to production of significant 11-cis-RAL in the treated eyes. Importantly, expression of Rpe65 and restoration of vision in the treated dogs was stable over the four-year study period. Finally, the rescued photoreceptors in these dogs were protected from the degeneration normally associated with LCA. According to the latest studies, more than 50 Briard dogs have been treated by gene therapy, with 95% showing restored vision (153). Similar results were seen with gene therapy of rpe65−/− mice, although here the restoration of vision only lasted a few months (154). The AAV-mediated gene therapy of LCA caused by RPE65 mutations is ready for clinical studies, having completed both proof-of-concept and biosafety studies in dogs, mice, and monkeys. The first LCA patients for the Phase I trials are expected to be enrolled during 2006 (153).

More recently, lrat−/− knockout mice were treated with recombinant AAV carrying a WT mouse lrat cDNA (155). These animals showed increased light sensitivity by ERG. Expression of exogenous LRAT was detected in the RPE cell layer near the injection site. Restoration of the retinoid cycle was detected by the appearance of 11-cis-RAL and a significant amount of regenerated rhodopsin (50% of WT) in the treated eye. Additionally, rescue of pupillary response in treated mice demonstrated intact neural signaling to the brain. These mice were also recipients of combined therapy involving gene therapy and chromophore supplementation by oral administration. Mice receiving both AAV-lrat gene therapy and 9-cis-retinyl acetate supplementation showed greater functional improvement than mice that received gene therapy alone. Such a combined-treatment approach might be applicable to humans.

Chromophore Supplementation Approach

The first experiments aimed at bypassing the biochemical defect caused by the absence of Rpe65 were performed by oral gavage of rpe65−/− mice with 9-cis-RAL (156, 157). 9-cis-RAL combines with opsin to form light-sensitive iso-rhodopsin (158). 9-cis-RAL was selected for the initial studies because of its lower cost and higher stability compared with 11-cis-RAL. Moreover, iso-rhodopsin has an absorbance maximum of 494 nm versus 502 nm for rhodopsin. This permits identification of the reconstituted iso-rhodopsin experimentally (122). Dietary supplementation of rpe65−/− mice with 9-cis-RAL restored light sensitivity to levels found in WT animals, as assayed by single-cell recordings and ERG. The amplitude of the saturating response increased with the number of doses. The improvement of rod functions has been observed up to six months after treatment (Figure 4a). Simultaneously, administration of 9-cis-RAL helped to preserve the morphology of the retina by improving interface contact between RPE and rod OS. Treatment with 9-cis-RAL decreased the content of apo-opsin in rpe65−/− mice, reducing constitutive activation of the phototransduction cascade, which led to slower photoreceptor degeneration. Similar recovery of visual function was observed following intraperitoneal injection of 11-cis-RAL into rpe65−/−mice (159) (see side bars Discovery of Vitamin A and Function of Vitamin A for additional information).

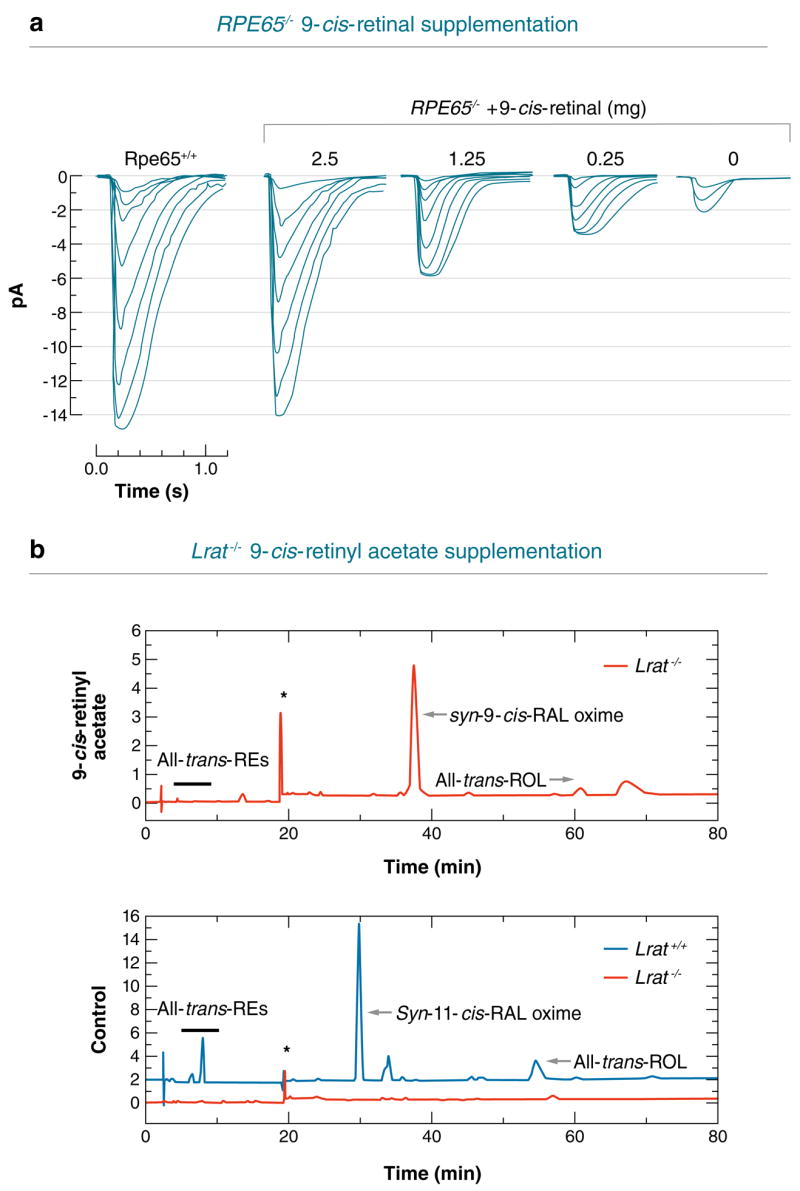

Figure 4.

Effects of chromophore supplementation and gene therapy on vision in rpe65−/− and lrat−/−knockout mice. (a) Single-cell recording stimulus response families of rpe−/− mice supplemented with 9-cis-RAL compared with rpe+/+ mice. (b) High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of retinoids present in the eyes of lrat−/− mice treated with 9-cis-retinyl acetate. The presented results were reproduced from References 155 and 157.

The therapeutic success of 9-cis- and 11-cis-RAL supplementation in rpe65−/−mice suggests that this approach may be useful to treat LCA caused by mutations affecting other visual cycle proteins such as LRAT. 9-cis-retinyl esters, 9-cis-RAL, and 9-cis-ROL were all effective in the rescue of visual pigments in lrat−/− mice by oral gavage (155) (Figure 4b). The 9-cis-retinyl esters, 9-cis-retinyl succinate and 9-cis-retinyl acetate are better suited for oral administration owing to their stability and low reactivity compared with 9-cis-RAL. Although light sensitivity was eightfold lower in treated lrat−/− versus WT mice, the response increased with multiple doses. This observation suggests that in the absence of LRAT, the 9-cis-chromophore may be recycled following phagocytosis of iso-rhodopsin containing OS by the RPE cells. The visual pigment was restored in lrat−/− mice 4–5 h after gavage and it was retained at the level of 50% of the initial amount for 120 days after a single dose. The formation of 9-cis-retinyl palmitate in the liver of 9-cis-retinyl acetate-gavaged lrat−/−mice points to the existence of alternate pathways of formation of retinyl esters such as ARAT or a retinyl trans-esterase (34, 37, 39).

DISCOVERY OF VITAMIN A

The effect of vitamin A on cures of dietary deficiency diseases has been known since ancient times. Since that time, the recommended treatment of the first symptoms of vitamin A deficiency, known as night-blindness, involved “continuous eating of… liver of goats.” The scientific approach that ultimately led to the discovery of vitamin A was given by E.V. McCollum. In 1913, performing nutrition experiments, he found that young rats on a diet of pure milk sugar, minerals, and olive oil failed to grow, while addition of butter fat or egg yolk extract restored their health. He proved the existence of the fat-soluble factor (then called fat-soluble factor A, as opposed to other dietary factors water-soluble B) by adding either butter extract to the olive oil, which became sufficient to support animal growth. In attempts to isolate and identify the factor, T.B. Osborne and L.B. Mendel, as well as H. Steenbock, confirmed the biological activity of the yellowish butter, egg yolk, and carrot extracts. However, they noticed that colorless liver and kidney extracts exhibited similar properties of growth promotion. This observation led to the hypothesis that fat-soluble factor A was only associated with yellow pigment and was being converted into an active colorless form. Ten years later, in 1930, T. Moore showed conversion of the yellow pigment (carotene) into colorless (retinol) by feeding rats with crystalline carotene and examining of their livers. He concluded that carotene was the precursor of vitamin A. At the same time, P. Karrer et al. isolated and determined the chemical structure of carotene and retinol. In 1947, O. Isler et al. performed the first total synthesis of retinol.

High doses of retinoids have been shown to be toxic in numerous studies (for a review, see Reference 160). One mode of retinoid toxicity results from the oxidation of retinol or retinaldehyde to retinoic acid by retinal dehydrogenase types 1, 2, 3, and 4 (161). All-trans-retinoic acid and its 9-cis isomer are important regulators of gene expression via the RAR and RXR nuclear receptors (162). Stimulation of these receptors leads to undesirable effects, including teratogenicity. However, acute and prolonged treatment of mice with 9-cis-retinoids did not cause obvious adverse effects such as reduced litter size, abnormal development, or growth retardation. This lack of apparent toxicity can be explained by the low levels of all-trans-retinoic acid detected in lrat−/− mice after administration of 9-cis-retinyl esters. The increased all-trans-retinoic acid levels observed after treatment usually disappeared within a day. Resistance to the potential toxicity of all-trans-retinoic acid seems to be related to inefficient esterification (storage) of the retinoids, leading to their rapid removal by oxidation and secretion. Although more toxicological studies are needed, the above described observation raises the hope for a trial of chromophore supplementation in humans.

FUNCTIONS OF VITAMIN A

Early observation based on the physiological response to a depletion of β-carotene or retinol pointed to three important functions of vitamin A in the processes of vision, epithelial differentiation, and growth. L.S. Fridericia & E. Holm scientifically confirmed the visual functions of vitamin A in 1925 by showing slower rates of visual purple regeneration in vitamin A–deficient rats. However, it was G. Wald who found that visual purple of the retina, called rhodopsin, contains the chromophore “retinene” (later identified by R. A. Morton to be retinaldehyde). Wald was able to show that one 11-cis isomer of retinaldehyde is preferentially bound to opsin and serves as a light acceptor undergoing light isomerization to the all-trans isomer. He also characterized molecular components of the visual cycle that leads to regeneration of 11-cis-RAL. Wald’s exceptional impact on understanding of the molecular basis of vitamin A action was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1967. Parallel to vision, S. B. Wolbach & P. R. Howe first reported the influence of vitamin A on epithelial cell differentiation in 1925. Moreover, the pathology of a vitamin A deficiency is manifested by reduction of bone growth and male and female reproduction. In the 1950s and 1960s, identification of plasma and cellular retinoid binding proteins by D.S. Goodman, F. Chytil & D.E. Ong had a great impact on the understanding of vitamin A transport and metabolism. The real breakthrough came with the discovery of the retinoic acid receptor in cell nuclei by P. Chambon & R.M. Evans in 1987. Activation or inhibition of specific gene transcription by the retinoic acid receptors explains at the molecular level many metabolic functions of vitamin A with regards to embryonic development, differentiation, and growth.

Retinoid Inhibitors of A2E Formation

Accumulation of fluorescent lipofuscin pigments in cells of the RPE is an important pathological feature of Stargardt disease (96, 110). These pigments are responsible for the “dark choroid” seen during fluorescein angiography (111) and the fundus autofluorescence seen by scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (112). The maximum emission wavelength of lipofuscin fluorescence in Stargardt patients is 650 nm (163), which corresponds to the emission maximum of A2PE-H2, an abundant A2E precursor in abcr−/− mice (10, 97). The cytotoxicity of A2E in RPE cells is well established. A2E has been shown to sensitize RPE cells to blue-light damage (164–166), impair the degradation of phospholipids from phagocytosed OS (167), induce the release of pro-apoptotic proteins from the mitochondria (168, 169), and destabilize cellular membranes through its properties as a cationic detergent (170–172). Further, irradiation of A2E with blue (430 nm) light resulted in a series of oxirane products containing up to nine epoxide rings, formed by the addition of singlet oxygen to double bonds along the polyene chains (113). A2E oxiranes were shown to induce DNA fragmentation by forming adducts with purines and pyrimidines in cultured ARPE-19 cells (173, 174), representing still another mechanism of A2E cytotoxicity. As expected, lipofuscin accumulation, indicated by fundus autofluorescence, precedes macular degeneration and visual loss in Stargardt patients (175). Hence, the likely sequence for photoreceptor degeneration in Stargardt disease is (a) lipofuscin accumulates in cells of the RPE; (b) RPE cells begin to function abnormally and ultimately degenerate owing to A2E-mediated cytotoxicity; and (c) the photoreceptors die secondary to loss of the RPE support-role (176), resulting in blindness. In Stargardt disease, the greatest concentration of lipofuscin is seen in RPE cells overlying the perifoveal region of the macula (96). The macula is located at the optical center of the retina and contains the highest density of photoreceptors. The vulnerability of the macula in Stargardt and other macular degenerations is due to the increased ratio of photoreceptors to RPE cells (177) and high incident light in this region.

Lipofuscin accumulation in the RPE is not limited to Stargardt disease. Increased fundus autofluorescence by scanning laser ophthalmoscopy is commonly seen in patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (178–180). The fluorescent material that accumulates in the aged RPE has spectral properties similar to A2PE-H2, observed biochemically in abcr−/− mice (10, 181). Strong fundus autofluorescence is also seen in patients with Best vitelliform macular dystrophy and a subset of patients with cone-rod dystrophy (182). Patients with dominant Stargardt disease, caused by mutations in the ELOVL4 gene, show a dark choroid by fluorescein angiography, again owing to lipofuscin in RPE cells (183, 184). In contrast, patients with LCA owing to mutations in the RPE65 gene show undetectable fundus autofluorescence (185), consistent with the role of Rpe65 as a retinoid isomerase (45–47) and the virtual absence of chromophore and lipofuscin in rpe65−/− mutants (48, 222). Lipofuscin accumulation in RPE cells has been observed in multiple animal models of inherited retinal and macular degeneration besides the abcr−/− mouse. For example, mice with a knockout mutation in the rdh8 gene, encoding an all-trans-RDH in photoreceptors, contain several-fold higher levels of A2E compared with WT eyes (16). Transgenic mice with a mutation in the elovl4 gene contain very high levels of A2E in the RPE (184). The Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) rat, with a mutation in the mertk gene for a receptor tyrosine kinase required for phagocytosis of shed OS (186), also accumulates A2E and its precursors in the RPE (187, 188). Humans with MERTK mutations have the inherited blinding disease, RP (189). Transgenic mice that express a mutant form of cathepsin D (mcd) in RPE cells manifest many features of AMD including photoreceptor degeneration, basal laminar and basal linear deposits, and autofluorescent lipofuscin pigments in the RPE (190, 191). Mice with knockout mutations in the genes for monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (Ccl-2), or its cognate chemokine receptor-2 (Ccr-2), also show features of AMD, including photoreceptor degeneration, basal deposits, thickening of Bruch’s membrane, choroidal neovascularization, and A2E accumulation in RPE cells (192).

It is easy to understand why mutations in the abcr or rdh8 genes lead to elevated A2E. Both genetic defects cause delayed clearance of all-trans-RAL (9, 16), the primary reactant in A2E biogenesis (193). But how can we explain A2E accumulation in retinal degenerations caused by mutations in the genes for proteins with no role in retinoid processing? Examples include genes for the Ca2+-activated Cl− channel, bestrophin (194); the putative fatty-acid elongation factor, ELOVL4 (184); the receptor kinase, MERTK (186); the lysosomal aspartate proteinase, cathepsin D (190, 191); and the monocyte chemoattractant protein plus its receptor, Ccl-2 and Ccr-2 (192). The answer to this question may be found in an unusual interaction between photoreceptors and RPE cells. Each morning, with the onset of daylight, the distal 10% of rod and cone OS break off and are phagocytosed by the overlying RPE (29). This means that nearly 10% of the total ocular retinoid pool passes daily through the RPE phagolysosomal system. One mouse eye contains ~500 pmol of rhodopsin (114, 195), thus ~50 pmol retinal transits through RPE phagolysosomes per day. However, the total content of A2E in a five-month-old WT mouse is less than 2 pmol per eye (9). Thus, only a tiny fraction of retinaldehyde phagocytosed by the RPE normally accumulates as A2E. The RPE must therefore be very efficient at blocking net synthesis of this toxic fluorophore. The RPE becomes progressively less efficient at eliminating or preventing the formation of A2E after being compromised by a genetic, immunologic, or environmental insult. Given its cytotoxicity, A2E accumulation is probably a self-accelerating process.

Accumulation of A2E with subsequent poisoning of the RPE appears to be an etiologic factor in retinal and macular degenerations of multiple causes. Inhibiting A2E formation should therefore slow the progression of visual loss in diseases associated with lipofuscin autofluorescence. Several approaches have been tested or proposed to slow accumulation of A2E. All have an effect on visual-cycle retinoids and ultimately limit the formation of all-trans-RAL (Figure 5). The first approach was to prevent photoisomerization of 11-cis-RAL by raising abcr−/− mice in total darkness. After 18 weeks, levels of A2E in WT and abcr−/− mice were similar, while A2E levels were 10-fold higher in the eyes of abcr−/− mice raised under cyclic light (10). Also, when abcr−/− mice were reared under cyclic light for 12 weeks, then transferred to total darkness for an additional 16 weeks, A2E levels in these 28-week-old mice were identical to the levels in 12-week-old abcr−/− mice reared under cyclic light (10). These environmental manipulations established that A2E synthesis could be blocked by inhibiting formation of all-trans-RAL. Levels of all-trans-RAL are increased only about two-fold in abcr−/− versus WT retinas following light exposure despite massive accumulation of A2E (9, 10). Thus, only a modest decrease in all-trans-RAL levels is required to slow dramatically the rate of A2E accumulation.

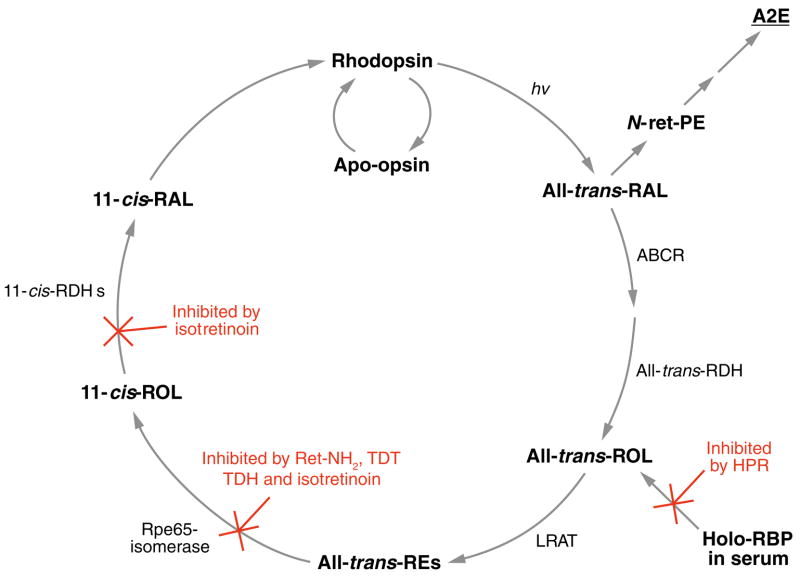

Figure 5.

Simplified visual cycle showing sites of action for the inhibitors of N-retinylidene-N-retinyl ethanolamine (A2E) formation. All-trans-RAL released by photoactivated rhodopsin condenses with phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) in disc membranes to form N-retinylidene-PE (N-ret-PE). Secondary condensation of N-ret-PE with another all-trans-RAL, followed by electrocyclization, hydrolysis of the phosphate ester, and oxidation yields A2E. Pharmacologic interventions that reduce light-dependent formation of all-trans-RAL greatly reduce the probability of this secondary condensation and inhibit formation of A2E. N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide (HPR) acts to reduce levels of holo-retinol binding protein (RBP) in serum. Rpe65-mediated isomerization can be blocked by retinylamine (Ret-NH2), the farnesyl-containing analogues, TDH and TDT, and isotretinoin. Isotretinoin also inhibits 11-cis-ROL dehydrogenase (11-cis-RDH).

A more practical approach to limiting light-dependent formation of all-trans-RAL is to slow synthesis of 11-cis-RAL by inhibiting the visual cycle pharmacologically. The first attempt was with isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid or Accutane®), a drug commonly used for the treatment of acne. An occasional side effect of Accutane® is reduced night vision (196). This effect is due to its inhibitory effect on 11-cis-RDH in RPE cells (197, 198) (Figure 5). Isotretinoin also binds to Rpe65 (199) and therefore might also inhibit the isomerase. Treatment of WT albino rats with isotretinoin prevented light-induced retinal damage, prompting the suggestion that this visual-cycle inhibitor may be useful for treating retinal or macular degenerations in humans (211). Treatment of abcr−/− mice with isotretinoin completely blocked new synthesis of A2PE-H2, A2E, and A2E-oxiranes (114, 200). Electron microscopic analysis showed reduced lipofuscin pigments in the treated animals (200). ERG of the treated animals showed delayed recovery of rod sensitivity following exposure to bright light, but otherwise normal visual function. These data validated the strategy of inhibiting the visual cycle pharmacologically as a mechanism to slow A2E accumulation in Stargardt and other lipofuscin-based diseases. Unfortunately, isotretinoin at doses sufficient to inhibit the visual cycle has unacceptable side effects. It is therefore unsuitable for long-term treatment of patients with macular degeneration.

N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide (HPR) (Figure 1c) is a retinoid analog that has been used for approximately 20 years as a chemotherapeutic agent to treat cancer. One action of HPR is to reduce serum levels of vitamin A by competing for binding sites on RBP (201). HPR binding to RBP prevents its interaction with transthyretin, causing loss of RBP to glomerular filtration (202). Unlike other tissues, the eye is highly dependent on RBP to deliver all-trans-ROL from serum. Mice with a knockout mutation in the rbp gene have a predominantly ocular phenotype (203). Treatment of abcr−/− mice with HPR at doses similar to those used in humans for treating cancer (2.5–10.0 mg kg−1 day−1) arrested the accumulation of A2E and its precursors (204) (Figure 5). Lipofuscin autofluorescence in the RPE, assessed by laser-scanning microscopy, was also dramatically reduced in HPR-treated mice (204). ERG of HPR-treated WT and abcr−/− mice showed slightly delayed recovery of rod sensitivity (delayed dark adaptation) following exposure to bright light, but otherwise normal visual function (204). Given the established safety of HPR in humans during clinical trials (205), these observations suggest that HPR may be useful for treatment of retinal and macular degenerations associated with lipofuscin accumulation, such as Stargardt disease. RBP-deficient mice have impaired retinal function early in life owing to low circulating levels of retinol (206). On a vitamin A–sufficient diet they acquire normal vision by 5 months of age. RBP is expressed by many tissues, including the eye and liver. Liver-derived RBP is responsible for the mobilization of retinol from hepatic stores. Ectopic, muscle-specific expression of human RBP on a rbp−/− background is sufficient to recover visual function (207). The role of RPE-expressed RBP in the visual cycle or retinol transport is not clear.

Positively charged retinoids, such as retinylamine (Ret-NH2), are inhibitors of the isomerization reaction in bovine RPE microsomes (208). Consistently, mice treated with all-trans-Ret-NH2 showed normal dark-adapted visual function by ERG, but delayed dark adaptation following light exposure. Ret-NH2 is reversibly N-acylated by LRAT to form inactive retinylamides (209), which prolongues the inhibitory effect. These observations suggest that Ret-NH2 may also be useful to inhibit A2E formation in maculopathies caused by lipofuscin accumulation. Mice treated with Ret-NH2 were resistant to light-induced retina damage.

Two farnesyl-containing isoprenoids (TDT and TDH) have been shown to bind Rpe65 in vitro (210). Administration of TDT and TDH to abcr−/− mice caused delayed dark adaptation by ERG and reduced A2E levels (210). Nothing is known about the toxicity or potential carcinogenicity of these agents. If safe, however, these data suggest that TDT and TDH may also reduce lipofuscin accumulation in humans.

What deficits in visual function might be expected in humans taking visual-cycle inhibitors? Sensitivity of the visual system in vertebrates is only limited by the efficiency of photon capture (quantum catch) in very dim light. Thus, a patient with a partially inhibited visual cycle would notice no changes in daylight vision. In dim light, the rate of photoisomerization, by definition, is very slow. Hence, a fully dark-adapted patient on visual-cycle inhibitors would start with a “full tank” of rhodopsin and would notice no change in visual performance as long as he remained in dim light. The effect of visual cycle inhibitors would be felt during transitions from bright to dim light. With pharmacologically slowed rhodopsin regeneration, a patient on treatment would take longer to dark-adapt. This would be felt, for example, upon entering a darkened theater or driving during daytime into a dimly lit tunnel. The severity of this effect would be influenced by the site of pharmacologic inhibition in the visual cycle. Isotretinoin, which effects the final catalytic step in the visual cycle (Figure 5), dramatically slowed dark adaptation in WT and abcr−/− mice (114, 200). The milder delay in dark-adaptation observed in WT and abcr−/− mice treated with HPR versus isotretinoin (200) may arise because HPR does not inhibit or antagonize any proteins in the visual cycle (Figure 5). Instead, HPR reduces the amount of all-trans-ROL entering the RPE, thereby lowering the steady-state levels of all intraocular retinoids. If these drugs are effective at slowing the progression of blindness in patients with retinal or macular degenerations associated with lipofuscin-accumulation, the functional penalty of delayed dark adaptation will probably be deemed worthwhile.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Our understanding of the mechanisms involved in visual-pigment regeneration is progressing rapidly. This understanding has stimulated the development of new approaches to treat inherited retinal diseases caused by defects in visual cycle proteins. The availability of experimental animals with spontaneous or engineered mutations in the genes for these proteins has been invaluable to this progress. Three therapeutic strategies have been considered.

Gene therapy involves the introduction of a normal gene within a recombinant virus for expression in a population of cells affected by a disease-causing mutation. Fortunately, most steps of the visual cycle take place within the RPE, a cell type that is easy to target owing to its high phagocytotic potential. Gene therapy has been successful in the treatment of mouse and dog models for LCA caused by mutations in RPE65. Clinical trials in humans with RPE65-mediated LCA are set to begin soon. However, the total number of patients with this subtype of LCA is very small. Successful gene therapy with RPE65 will represent an exciting proof of concept, but at best will only restore vision to a tiny subset of patients that suffer from inherited blindness.

Chromophore replacement therapy involves administration of natural or artificial chromophore or chromophore precursor. This strategy is analogous to treating an inborn error of metabolism by providing a metabolite downstream of the blocked step. It is suitable for diseases caused by impaired chromophore biogenesis, such as RPE65-mediated LCA. A hypothetical drawback of this approach is the accumulation of toxic or teratogenic retinoic acid with prolonged retinoid supplementation. Mice that received prolonged supplementation with 9-cis-retinoids exhibited no signs of toxicity.

Therapeutic inhibition of the visual cycle involves the use of retinoid analogs to slow the biosynthesis of 11-cis-RAL chromophore. By partially depleting rhodopsin, the amount of all-trans-RAL released by light exposure is reduced. This approach has been shown to arrest the accumulation of toxic lipofuscin fluorophores in the RPE of abcr−/− and WT mice (114, 200, 204). The functional penalty for treating with visual cycle inhibitors is delayed dark adaptation, although this effect was mild in mice. A hypothetical drawback of slowing rhodopsin regeneration is that the presence of apoopsin could lead to constitutive activation of the visual transduction cascade and might cause photoreceptor degeneration (79). However, no photoreceptor degeneration was seen in mice following prolonged treatment with isotretinoin or HPR (114, 200, 204). This lack of degeneration is probably due to the modest reduction in rhodopsin required to inhibit A2E accumulation. On the other hand, visual cycle inhibitors prevented light-induced damage to the retina (211), suggesting a possible protective effect of these drugs.

The present accomplishments in this research field were made possible by the availability of mice with modified or disrupted genes for retinoid cycle proteins. In most cases, these mice are close models of the cognate human diseases. However, retinal anatomies differ between experimental animals and humans with respect to the presence of a macula and the distribution of rods and cones. Also, quantitative differences are seen in the levels of visual retinoids and the specific activities of retinoid-processing enzymes.

The discovery of a cone-specific pathway for chromophore regeneration operating in diurnal animals has important implications for human disease. With the advent of artificial lighting, the functioning of cones is far more important than rods for useful vision in humans. Rods, however, are important for night vision and are necessary for cone survival. Preserving cone function by maintaining rod survival at the expense of rod function could be a major theme in the future development of therapies for macular degeneration, Stargardt disease, and RP.

Several routes of drug delivery are possible in the treatment of ocular diseases with retinoid analogs. As discussed, retinoids can be delivered orally, with excellent delivery to the eye. Potentially, retinoid drugs could also be delivered by eye drops, intraocular injection into different compartments of the eye, or periorbital injections into the fat surrounding the eye. Finally, the drugs could be released from slow-release devices that encapsulate the drug. These approaches will lower potential toxicity compared with the drugs delivered systemically.

Until recently, the retina has not been accessible for high-resolution images. New applications of two-photon microscopy that exploit the intrinsic fluorescence of retinoids permit visualization of RPE-cell structures in live animals (41, 212). With further development, these techniques may provide new information about retinoid metabolism and the response to treatments in humans.