Abstract

Infection with Helicobacter pylori cagA-positive strains is associated with gastritis, ulcerations, and gastric cancer. CagA is translocated into infected epithelial cells by a type IV secretion system and can be tyrosine phosphorylated, inducing signal transduction and motogenic responses in epithelial cells. Cellular cholesterol, a vital component of the membrane, contributes to membrane dynamics and functions and is important in VacA intoxication and phagocyte evasion during H. pylori infection. In this investigation, we showed that cholesterol extraction by methyl-β-cyclodextrin reduced the level of CagA translocation and phosphorylation. Confocal microscope visualization revealed that a significant portion of translocated CagA was colocalized with the raft marker GM1 and c-Src during infection. Moreover, GM1 was rapidly recruited into sites of bacterial attachment by live-cell imaging analysis. CagA and VacA were cofractionated with detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs), suggesting that the distribution of CagA and VacA is associated with rafts in infected cells. Upon cholesterol depletion, the distribution shifted to non-DRMs. Accordingly, the CagA-induced hummingbird phenotype and interleukin-8 induction were blocked by cholesterol depletion. Raft-disrupting agents did not influence bacterial adherence but did significantly reduce internalization activity in AGS cells. Together, these results suggest that delivery of CagA into epithelial cells by the bacterial type IV secretion system is mediated in a cholesterol-dependent manner.

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative microaerophilic gastric pathogen that infects approximately one-half of the human population (35, 39, 61). Persistent colonization is associated with chronic inflammation processes, gastric atrophy, gastric adenocarcinoma, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (39). Two complete genomic sequences and other results have demonstrated the unexpectedly high level of genetic heterogeneity of this peculiar microbe and its extraordinary ability to adapt to different ecological niches worldwide (2, 11, 55).

Virulent H. pylori strains possess a type IV secretion system (TFSS) encoded by a cag pathogenicity island, which injects CagA directly into infected host cells (8, 37). Translocated CagA, after tyrosine phosphorylation by Src family kinases (37, 48), induces cell signaling, which leads to the stimulation of cell dissemination and the “hummingbird” phenotype in gastric epithelial cells (9, 47). Nonphosphorylated or dephosphorylated CagA can also be phosphorylated by Abl, a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase that regulates cell morphogenesis and motility (43). H. pylori strains with a cag pathogenicity island have also been reported to be associated with higher levels of interleukin-8 (IL-8) production in gastric epithelial cells (15, 19, 22, 49, 64). Expression of CagA resulted in translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus and activation of IL-8 transcription via a Ras-Raf-Mek-Erk-NFκB signaling pathway, which suggests that CagA is a determining factor in inducing IL-8 release (13).

The other nonconserved virulence factor of H. pylori is an exotoxin, vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA), which induces vacuolation, alters mitochondrial membrane permeability, and inhibits T-cell proliferation (for a review, see reference 18). Several types of evidence suggest that VacA intoxication relies on cellular lipid rafts, which are dynamic microdomains containing cholesterol, sphingolipids, and glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins in the exoplasmic leaflet of the lipid bilayer and are implicated in cellular signaling, membrane transport and trafficking, and membrane curvature (for reviews, see references 26 and 51). First, cellular cholesterol is required for VacA cytotoxicity in cultured gastric cells (23, 40, 46), and VacA migrates with tubulovesicular structures that contain glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins to enter cells for its full vacuolating activity (23, 29, 44). Furthermore, using a cold detergent extraction method, VacA has been isolated primarily on detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs) that are generally considered to be fractions of rafts (23, 40, 46). It has been noted that cholesterol-rich microdomains are also utilized by other bacterial toxins, including cholera toxin (38) and aerolysin (1), for entry or oligomerization. Another role of cellular cholesterol in H. pylori infection has recently been reported by Wunder et al.; these authors found that H. pylori drifts toward cellular cholesterol and absorbs it for subsequent glucosylation to evade phagocytosis (63).

Interestingly, VacA and CagA inversely regulate the activity of the nuclear factor of activated T cells (25). Asahi et al. reported that translocated CagA was isolated on DRMs, in which tyrosine-phosphorylated GIT1/Cat1 molecules, which are substrates of the VacA receptor (receptor-type protein-tyrosine phosphatase), were also located (5). These results suggest that translocated CagA is raft associated and hint that cholesterol-rich microdomains may be required for CagA delivery into the target cell by the TFSS. In this investigation, we utilized AGS gastric epithelial cells, which are frequently used as a model system, to study whether cellular cholesterol is involved in CagA translocation and phosphorylation during H. pylori infection. We also investigated whether depletion of cellular cholesterol influences the CagA-induced hummingbird phenotype and IL-8 response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and cell culture.

H. pylori 26695 (ATCC 700392; CagA+ VacA+) was used as the reference strain. Isolation, identification, and storage of H. pylori strains were performed as described elsewhere (28, 65). The bacteria were routinely cultured on brucella agar plates (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with 6 μg/ml vancomycin and 2 μg/ml amphotericin B in a microaerophilic atmosphere at 37°C for 2 to 3 days. Human gastric adenocarcinoma cell line AGS cells (CRL 1739; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultured in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in F-12 medium (HyClone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% decomplemented fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone). No antibiotic was used in this study.

Construction of H. pylori isogenic mutants.

The isogenic mutant H. pylori ΔvacA::cat was generated by insertion of the cat fragment derived from pUOA20 (60) into vacA of H. pylori through allelic replacement and selection of chloramphenicol-resistant clones (59). The vacA gene fragment was amplified from the strain 62 chromosome by PCR as previously described (65) and was cloned into plasmid pGEMT (Promega, Madison WI), yielding plasmid pGEM-vacA. The forward and reverse oligonucleotide primers designed for PCR amplification of the cat sequence were catMfeI_F (TGCGTCAATTGGATTGAAAAGTGG) and catMfeI_R (AGGACGCACAATTGTCGACAGAGA), respectively. These primers introduced an MfeI site (underlined) at the 5′ and 3′ ends. The amplified product was digested with MfeI and ligated into the MfeI site of pGEM-vacA to obtain plasmid pGEM-vacA-cat with a cat gene inserted into vacA (vacA::cat). A vacA::cat mutant was generated by transforming pGEM-vacA-cat into the parental strain H. pylori 26695 by allelic replacement and selecting chloramphenicol-resistant clones using the natural transformation method described by Wang et al. (58).

To generate cagA (ΔCagA), vacA cagA (ΔVacAΔCagA), and cagE (ΔCagE) knockout strains, similar procedures were performed using the cat cassette, the kanamycin resistance cassette (Kmr) from pACYC177 (45), and the erythromycin resistance cassette (Eryr) from pE194 (24). The primers used for PCR amplification of Kmr from pACYC177 had an introduced NheI site (underlined) and were forward primer KmNheI_F (GGAAGATGCGCTAGCTGATCCTTCAAC) and reverse primer KmNheI_R (CCCGTCAAGCTAGCGTAATGCTCTGC). The primers used for PCR amplification of Eryr from pE194 had an introduced XbaI site (underlined) and were forward primer EryXbaI_F (CAATAATCTAGACCGATTGCAGTATAA) and reverse primer EryXbaI _R (GACATAATCGATCTAGAAAAAATAGGCACACG). Correct integration of the antibiotic resistance cassettes into the target genes of the chromosome was verified by PCR. Western blot analysis was performed to confirm that the insertion of cassettes abolished expression of VacA and/or CagA, as well as CagE.

Treatment with raft disruptors or usurpers in AGS cells.

AGS cells (1 × 105 cells) were cultured in F-12 (HyClone) containing 10% decomplemented FBS (HyClone) in 24-well plates for 20 h at 37°C. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times and either were not treated or were treated with the following agents for 1 h at 37°C in a serum-free F-12 medium: (i) methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) (1.0, 2.5, and 5.0 mM; Sigma-Aldrich), (ii) lovastatin (10, 20, and 50 μM; Sigma-Aldrich), and (iii) nystatin (50 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). To remove MβCD or nystatin, cells were washed with PBS three times and were cultured in fresh culture medium supplemented with 10 μM lovastatin to inhibit cellular cholesterol biosynthesis. To restore cholesterol, 400 μg/ml of water-soluble cholesterol (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to MβCD-treated AGS cells, which were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C (16). To observe the effects of cholera toxin subunit B (CTX-B), AGS cells were pretreated with CTX-Β (20 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h and then infected with H. pylori. The viability of AGS cells was determined by using trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich).

Detection of cellular cholesterol.

To measure the level of cellular cholesterol, AGS cells that were not treated or were treated with various agents (MβCD, lovastatin, or MβCD, followed by cholesterol replenishment) were washed three times with PBS, harvested, and disrupted by ultrasonication (three 10-s bursts at room temperature). The cholesterol contents were then measured using an Amplex Red cholesterol assay kit (Molecular Probes) as described in the manufacturer's instructions. The percentage of remaining cholesterol after pretreatment with MβCD or lovastatin was determined as follows: (measured fluorescence of treated cells obtained from a standard curve/total fluorescence of untreated cells) × 100.

Antibodies.

Polyclonal rabbit anti-VacA antisera were prepared with the recombinant VacA protein consisting of 33 to 856 amino acids of ATCC 49503 VacA (29). The polyclonal mouse anti-BabA antibody was prepared with the recombinant BabA protein of strain v344 (33). Mouse polyclonal anti-urease antisera were produced against the recombinant UreA from strain 184 (65). Rabbit and mouse anti-CagA antibodies were purchased from Austral Biologicals. Goat anti-CagA, goat anti-actin, and rabbit anti-c-Src antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (4G10) was purchased from Upstate. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-rabbit, Cy5-conjugated anti-goat, and Cy5-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies were purchased from Chemicon. FITC-conjugated CTX-B and Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated CTX-B were purchased from Molecular Probes (Carlsbad, CA), and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated CTX-B was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-transferrin receptor antibody was purchased from BD Biosciences. The working dilution of the mouse anti-VacA, anti-BabA, and anti-UreA, rabbit anti-c-Src, and goat anti-CagA antibodies was 1:100; the working dilution of the goat anti-actin antibody was 1:500. The working dilutions of all other antibodies were those suggested by the manufacturers.

Confocal microscopic analysis of AGS cells infected with H. pylori.

AGS cells (5 × 105 cells) were seeded on coverslips in six-well plates and incubated for 20 h. Cells were then washed and treated with or without 5.0 mM MβCD for 1 h. After three washes with PBS to remove MβCD, fresh medium supplemented with 10 μM lovastatin was added to the cells. Cells were then not treated or infected with wild-type H. pylori at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 for 6 h. After three washes with PBS, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 min, and blocked with 3% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were stained and observed with a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM 510; Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) with a ×100 objective (oil immersion; aperture, 1.3).

Live-cell imaging of AGS cells infected with H. pylori.

AGS cells were seeded onto coverslips (1.8 by 1.8 cm) at 37°C for overnight culture and then washed with cold PBS three times. To label GM1, cells were mixed with FITC-conjugated CTX-B (5 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.1% bovine serum albumin in PBS, which was followed by incubation on ice for 30 min and three washes with cold PBS. For synchronized infection, cells were infected with H. pylori at an MOI of 50, and plates were then immediately centrifuged at 600 × g for 5 min at 4°C (referred to as a synchronized MOI of 50). Infected cells were then incubated at 37°C for 2 min and visualized with a Zeiss LSM510 META confocal laser scanning microscope. Images of serial optical sections (1024 × 1024 pixels) were obtained using a 40× C-Apochromate (Carl Zeiss) lens. Laser (488-nm) and phase-contrast images were collected in a 15-s interval. Live-cell imaging experiments were repeated independently at least twice. The images were acquired blindly to minimize operator bias.

Immunoprecipitation.

AGS cells were plated in six-well plates at a concentration of 1.5 × 105 cells per well and cultured overnight to obtain 80% confluence. Cells were then washed and treated with or without the indicated concentrations of MβCD in the serum-free medium for 1 h. After three washes with PBS to remove MβCD, cells were incubated in the absence or presence of 400 μg/ml of water-soluble cholesterol at 37°C for another 1 h. Cells were then washed once with PBS and not infected or infected with H. pylori. For synchronized infection, cells were infected with H. pylori at an MOI of 50, and plates were then immediately centrifuged at 600 × g for 5 min, which was followed by incubation at 37°C for 6 h. Then cells were washed with PBS three times and lysed in ice-cold immunoprecipitation buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) with 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), 2 μg/ml aprotinin, and 2 μg/ml leupeptin. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 min. The resultant supernatant containing 1 mg of proteins was subsequently subjected to immunoprecipitation using 10 μg of rabbit anti-CagA polyclonal antibody and 100 μl of protein A/G PLUS-Agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 4οC overnight. The precipitates were washed three times with immunoprecipitation buffer and once with TBS buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2) and then boiled with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.05% brilliant blue R) at 95οC for 10 min. Immunoprecipitates were then resolved by 6% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Pall, East Hills, NY). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in TBS buffer containing 0.01% Tween 20 at room temperature for 1 h and then incubated overnight with mouse anti-CagA or mouse anti-phosphotyrosine (4G10) antibodies (dilution, 1:1,000) at 4οC. The blots were washed and then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) at a dilution of 1:3,000. The proteins of interest were visualized by using the enhanced chemiluminescence assay (Amersham Pharmacia, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) and were detected using an LAS-3000 imaging system (Fujifilm, Valhalla, NY).

Isolation and analysis of lipid rafts.

AGS cells (1 × 106 cells) were infected with H. pylori at a synchronized MOI of 50 at 37°C for 6 h and subsequently lysed with ice-cold 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in TNE buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA) containing a 1:100 dilution of protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) on ice for 1 h. Optiprep (Axis-Shield, Dundee, United Kingdom) was added to the lysates at the bottom of an ultracentrifuge tube, and the contents were adjusted to obtain a final Optiprep concentration of 40% in 600 μl (total volume), overlaid with 500 μl of 35% Optiprep, 500 μl of 30% Optiprep, 500 μl of 25% Optiprep, or 500 μl of 20% Optiprep, and topped with TNE buffer containing no Optiprep. The gradients were centrifuged at 160,000 × g for 18 h at 4°C using an RPS56T rotor (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Fractions were collected from top to bottom, and proteins were precipitated with 6% trichloroacetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

To analyze the distribution of proteins in the fractions using ice-cold Triton X-100 flotation experiments, aliquots of each fraction were mixed with SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and the proteins were resolved by 6% SDS-PAGE under denaturing conditions, followed by immunoblot analysis. After transfer onto nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond-C extra; Amersham Pharmacia), the blots were blocked with 5% skim milk in TBS buffer containing 0.01% Tween 20 at room temperature for 1 h and then incubated with individual primary antibodies (anti-transferrin receptor [1:1,000], anti-VacA [1:1,000], anti-CagA [1:1,000], and anti-UreA [1:1,000]) at 4°C overnight. The proteins were probed with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:3,000). To detect ganglioside GM1, 100-μl portions of the fractions collected from the Optiprep gradient were applied to a nitrocellulose membrane in a manifold dot blot apparatus under suction. The membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk in TBS buffer containing 0.01% Tween 20 at room temperature for 1 h and then probed with HRP-conjugated CTX-B (0.2 μg/ml) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Pharmacia).

Quantitative analysis of the AGS cell hummingbird phenotype.

AGS cells (4 × 105 cells) were cultured in 24-well plates containing F-12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C for 20 h. After one wash with PBS, cells were treated or not treated with MβCD, or they were treated with MβCD followed by cholesterol replenishment. MβCD-treated cells were washed three times with PBS to remove the MβCD and then mixed with fresh medium supplemented with 10 μM lovastatin. Cells were then not infected or infected with the wild-type or ΔCagA H. pylori strain at a synchronized MOI of 100 for 6 h. The percentage of elongated cells was determined by a blind investigator in order to determine the numbers of cells having the hummingbird phenotype. Elongated cells were defined as cells that had thin needlelike protrusions that were >20 μm long and a typical elongated shape, as reported by Backert et al. (7). Cells that were the normal shape or had the atypical elongated phenotype due to MβCD treatment (less than 20 μm long and more sphere shaped than the H. pylori-induced cells) were considered nonelongated cells. One hundred AGS cells from each photograph were counted and evaluated. All samples were examined in triplicate in at least three independent experiments. The data described below are the means of three independent experiments.

IL-8 measurement.

To detect IL-8 released by gastric epithelial cells during H. pylori infection, the levels of IL-8 in supernatants from the AGS cells were determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a sandwich ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Infection was performed using a synchronized MOI of 100. Supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C before analysis.

Bacterial adherence and internalization assays.

H. pylori adherence and internalization activity in AGS cells was investigated using a standard gentamicin assay as previously described (32). AGS cells, not treated or pretreated with MβCD, nystatin, or CTX-B, were added to mid-logarithmic-phase bacteria at an MOI of 50 and incubated at 37°C for 6 h. To determine the number of cell-associated bacteria, infected cells were washed three times to remove unbound bacteria and then lysed with distilled water for 10 min. Lysates were diluted in PBS, plated onto brucella blood agar plates, and cultured for 4 to 5 days, after which the CFU were counted. To determine the number of viable intracellular bacteria, infected cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated with 100 μg/ml of the membrane-impermeable antibiotic gentamicin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1.5 h at 37°C to remove extracellular bacteria, which was followed by the same procedures to determine the number of CFU. We counted viable epithelial cells for normalization of the samples. The adhesion or internalization activities were expressed as the means of at least six independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Statistical analysis.

Student's t test was used to calculate the statistical significance of the experimental results for two groups; a P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Treatment with MβCD or lovastatin extracts cellular cholesterol and GM1 from rafts of AGS cells.

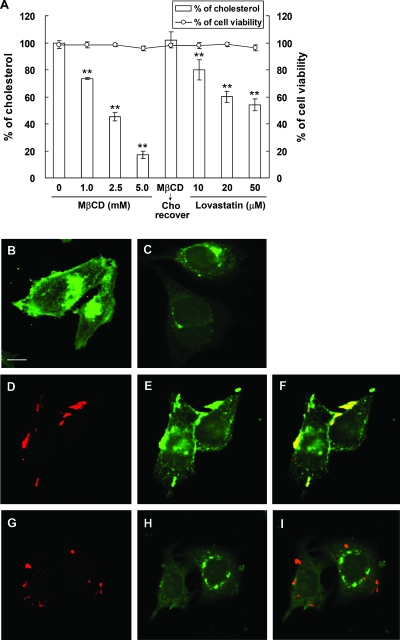

MβCD was first evaluated to determine whether it could extract eukaryotic cholesterol from lipid rafts of AGS cells (50). As shown in Fig. 1A, the level of cellular cholesterol was reduced with MβCD pretreatment for 1 h in a dose-dependent manner. When cells were treated with 5.0 mM MβCD, >80% of cellular cholesterol was extracted, which could later be restored by adding cholesterol (Fig. 1A). We also evaluated the cellular cholesterol level when cells were treated with lovastatin, an inhibitor of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase for cellular cholesterol biosynthesis (21). As shown in Fig. 1A, lovastatin-treated cells contained progressively lower levels of cellular cholesterol as the concentration of lovastatin increased. On the other hand, cells remained essentially viable even when they were treated with 5.0 mM MβCD or 50 μM lovastatin.

FIG. 1.

The level of cellular cholesterol and GM1 was reduced when AGS cells were treated with MβCD or lovastatin. (A) Cholesterol levels of AGS cells treated with MβCD or lovastatin. AGS cells were treated as follows: (i) with various concentrations of MβCD (0, 1.0, 2.5, and 5.0 mM), (ii) with 5.0 mM MβCD and cholesterol (400 μg/ml) replenishment, and (iii) with various concentrations of lovastatin (10, 20, and 50 μM). Cells were then harvested for cholesterol detection (bars). The cell viability was hardly influenced under these conditions, as determined by the exclusion of trypan blue. The data are the means ± standard deviations from at least triplicate independent experiments. Two asterisks indicate that the P value was <0.01 compared to untreated controls, as determined by Student's t test. (B to I) Confocal microscopic analysis of noninfected and infected AGS cells. Cells that were not treated (B) or were treated with MβCD (C) were stained with FITC-conjugated CTX-B to visualize GM1. For infection experiments, untreated cells (D to F) or MβCD-treated cells (G to I) were infected with H. pylori strain 26695 (MOI, 50) at 37°C for 6 h. Infected cells were fixed and then probed with specific markers for BabA (red) (D and G) and GM1 (green) (E and H). Yellow in the merged images indicates colocalization (F and I). Scale bar, 10 μm.

Since cholesterol, along with GM1, sphingomyelin, and glycosphingolipids, is a constituent of lipid rafts (14, 66), we sought to investigate whether MβCD also extracted other raft-associated molecules, such as GM1 (36, 62), in AGS cells. The distribution of GM1 (stained by FITC-conjugated CTX-B) was visualized using a confocal microscope. Untreated cells exhibited a punctate GM1 staining pattern (Fig. 1B), indicating that there were distinct regions on the cell surface that were enriched with GM1. GM1 was also found around the perinuclear region, where GM1 is synthesized (56) (Fig. 1B). When cells were treated with MβCD, the extent of GM1 on the cell membrane was greatly reduced, indicating that MβCD extracted both the cholesterol and GM1 that were present on lipid rafts (Fig. 1C). Similar results were obtained when lovastatin was added to cells (data not shown).

We next visualized cells that were infected with H. pylori at 37°C for 6 h. In the absence of MβCD treatment, a portion of GM1 was mobilized to sites of bacterial attachment, as shown in Fig. 1D to F. Notably, some adhered bacteria were essentially colocalized with GM1, indicating that there was specific recruitment of raft-associated GM1 to sites of bacterial attachment (Fig. 1F). With MβCD pretreatment, a few bacteria were observed around the membrane of infected AGS cells (Fig. 1G). The amount of GM1 in the plasma membrane was greatly reduced (Fig. 1H), similar to the results shown in Fig. 1C. Accordingly, the extent of GM1 colocalization with bacteria was greatly reduced (Fig. 1I). Thus, our data demonstrated that GM1 clustering takes place at the site of H. pylori infection on the cell membrane.

Adhered H. pylori and translocated CagA are found in GM1-associated regions in infected AGS cells.

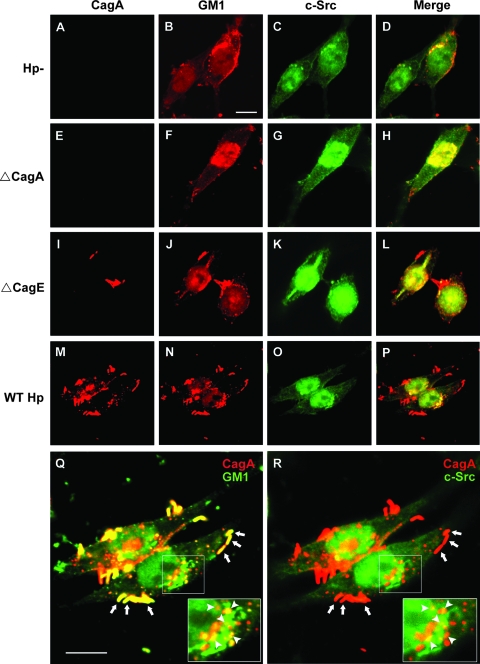

To visualize the distribution of CagA in infected AGS cells, the following agents were utilized: (i) anti-CagA antibody and (ii) anti-c-Src antibody. Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated CTX-B was used to visualize GM1. In noninfected AGS cells, c-Src and GM1 were observed around the plasma membrane or near the perinuclear region (Fig. 2A to D). Notably, a significant portion of c-Src was colocalized with GM1 (Fig. 2D), supporting the theory that c-Src is raft associated (20).

FIG. 2.

Distribution of adhered bacteria, translocated CagA, GM1, and c-Src in infected AGS cells. Untreated AGS cells (A to D), ΔCagA-infected cells (E to H), ΔCagE-infected cells (I to L), and wild-type H. pylori-infected cells (M to P) were fixed and stained with goat anti-CagA, rabbit anti-c-Src, and Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated CTX-B to visualize GM1, followed by Cy5-conjugated anti-goat and FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies. Red, CagA; pseudored, GM1; green, c-Src. Yellow in the merged images (D, H, L, and P) indicates colocalization of GM1 and c-Src. (M to R) AGS cells were cocultured with wild-type H. pylori at 37°C for 6 h and then fixed and stained, and this was followed by observation by confocal fluorescence microscopy as described above. For two merged images (panels Q [CagA and GM1] and R [CagA and c-Src]), the framed region was magnified, and the magnified images are shown in the lower right corner. Areas of colocalization of CagA and GM1 (Q) or CagA and c-Src (R) in the cell (right) are indicated by arrowheads. The adhered H. pylori bacteria in the cell (right) are indicated by arrows. Scale bars, 10 μm. Hp−, not treated with H. pylori; WT Hp, treated with wild-type H. pylori.

We next evaluated the distribution of CagA, GM1, and c-Src when AGS cells were incubated with a cagA knockout mutant (ΔCagA) or a cagE knockout mutant (ΔCagE), as CagE serves as an ATPase in the TFSS (for a review, see reference 12). For ΔCagA-infected cells, there was no CagA staining, as expected (Fig. 2E). The distribution of GM1 and c-Src (Fig. 2F to H) was similar to that in noninfected cells (Fig. 2B to D). For ΔCagE-infected cells, a few adhered bacteria were seen around the cell surface, as revealed by the presence of CagA staining (red) (Fig. 2I). GM1 and c-Src were also distributed near the plasma membrane and perinuclear region of infected cells (Fig. 2J to L). In contrast, there was no CagA staining in the cytosol. These results suggest that CagA translocation requires a functional TFSS, consistent with previous findings (53).

When cells were infected with wild-type H. pylori at 37°C for 6 h, CagA was seen around adhered bacteria on the cell surface (Fig. 2M). CagA was also observed inside the cells (Fig. 2 M), indicating that CagA was translocated into AGS cells. The distribution of GM1 and c-Src in infected cells was similar to that in noninfected cells, but there were more pronounced scattered aggregates (Fig. 2N and P). In accordance with the results shown in Fig. 1F, adhered bacteria were essentially colocalized at sites in the GM1-associated region, as shown in the merged CagA/GM1 image (Fig. 2Q). For translocated CagA, a significant portion of signals was found at sites where GM1 (Fig. 2Q) and c-Src (Fig. 2R) were colocalized. These data suggest that during infection adhered bacteria and a great portion of the translocated CagA were associated with membranes that contained GM1 and c-Src.

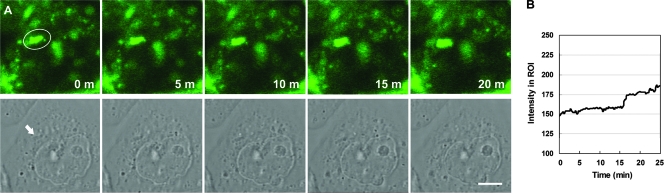

Confocal microscopy live-cell imaging was performed to visualize the distribution of GM1 around adhered bacteria in infected cells during the infection process. Cells were stained with FITC-conjugated CTX-B to label GM1 at 4°C, which was followed by synchronized infection at 4°C to ensure minimal membrane fluidity. After incubation at 37°C for 2 min, infected cells were quickly inspected to identify a region containing adhered bacteria (this process took 5 to 10 min) for subsequent time-lapse experiments (a 15-s series). As shown in Fig. 3A, the first image (zero time) showed that there was a bright GM1 signal around an adhered bacterium in the region of interest (ROI). At later times, accumulated GM1 signals were observed in the ROI (Fig. 3B). Notably, a small piece of a signal that was located at the right of the bacterium at zero time migrated gradually toward the bacterium and finally merged into it at 20 min (Fig. 3A, top panel). These results suggest that raft-associated GM1 was rapidly recruited to sites of bacterial attachment after the initial contact (within approximately 15 min) and continued mobilizing to these sites at later times.

FIG. 3.

GM1 is specifically recruited to the site of H. pylori attachment. (A) AGS cells were plated on coverslips, probed with FITC-conjugated CTX-B to visualize GM1, and then infected with H. pylori as described in Materials and Methods. Infected live cells were visualized using a Zeiss LSM510 META confocal laser scanning microscope for time-lapse experiments. Images were taken in 15-s series for a total of 25 min. Confocal images (488 nm) taken at different time points are shown in the top panels, while the corresponding phase-contrast images are shown in the bottom panels. The ellipse indicates an ROI, and the arrow indicates a bacterium attached to the cell. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B) The fluorescence intensity in the ROI was evaluated for all images.

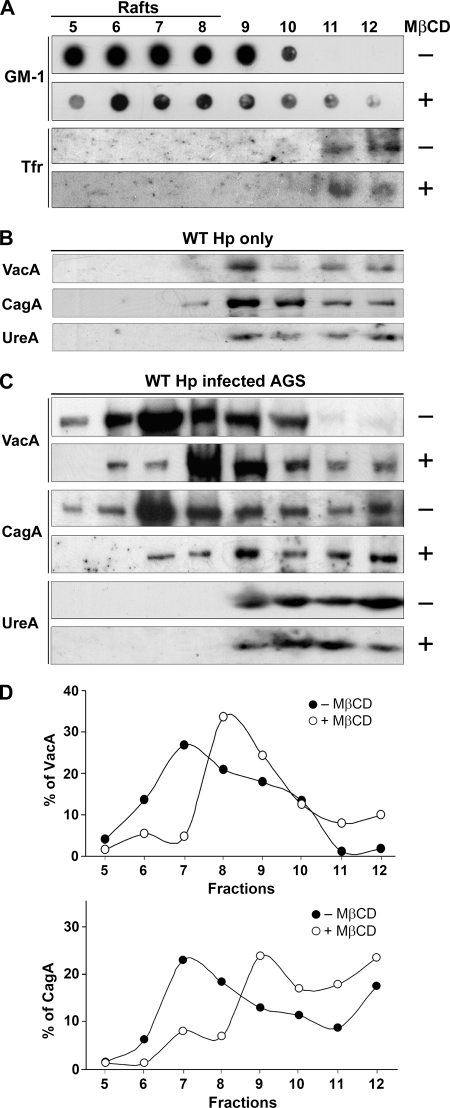

Cholesterol extraction from infected AGS cells results in the displacement of CagA and VacA from DRMs to non-DRMs.

After visualization of colocalization of adhered bacteria and CagA with raft-associated molecules (GM1) using the confocal microscope, we next investigated whether CagA was present in lipid raft microdomains during H. pylori infection by use of a cold detergent insolubility assay, a method commonly used for investigation of raft association (52). Samples were solubilized in cold Triton X-100, and DRMs were isolated using OptiPrep gradients. In untreated AGS cells (Fig. 4A), GM1 was enriched in DRMs in the top, lighter fractions (fractions 5 to 8), while the transferrin receptor (Tfr), a transmembrane protein localized to clathrin-coated pits, was associated with heavier fractions (fractions 11 and 12). When pure bacteria were subjected to the same treatment, three virulence factors (CagA, VacA, and urease [UreA]) appeared in heavier fractions, indicating that bacteria were efficiently lysed (Fig. 4B). For infected AGS cells, VacA was isolated primarily in DRM fractions (Fig. 4C), consistent with the previous finding that VacA enters epithelial cells via a raft-associated endocytic route (29, 44, 46). The major portion of CagA, interestingly, was also present in lighter fractions, and the peak was at fraction 7 (Fig. 4D), in accordance with the findings of Asahi et al. (5). In contrast, urease was found in non-DRM fractions. When pretreatment with 5.0 mM MβCD was used to extract cholesterol, the levels of VacA and CagA in the lighter fractions were significantly reduced (Fig. 4C). Moreover, the distribution of both proteins shifted to heavier fractions (Fig. 4D), analogous to the pattern seen for GM1. Urease remained in the nonraft fractions after MβCD pretreatment, as observed for the transferrin receptor. Thus, in AGS cells, VacA and CagA were primarily in DRMs, whereas urease was in non-DRMs. Upon cholesterol depletion, the VacA and CagA shifted from DRMs to non-DRMs.

FIG. 4.

The distribution of CagA and VacA in infected cells shifted from DRMs to non-DRMs upon cholesterol depletion. (A) Infected AGS cells were subjected to fractionation in an Optiprep density gradient at 4°C. Each fraction was assayed for GM1 with HRP-conjugated CTX-B using dot blot analysis and was assayed for the transferrin receptor with anti-Tfr antibody using Western blot analysis. (B) Pure bacteria were subjected to fractionation in an Optiprep density gradient at 4°C. Each fraction was assayed for VacA, CagA, and UreA using Western blot analysis. (C) AGS cells were infected with H. pylori 26695, which was followed by fractionation in an Optiprep density gradient at 4°C. For cholesterol depletion, cells were treated with 5.0 mM MβCD for 1 h prior to incubation. Each fraction was assayed for VacA, CagA, and UreA using Western blot analysis. (D) VacA (upper panel) and CagA (lower panel) signals in each fraction from panel C were detected and expressed as relative intensities. WT Hp, wild-type H. pylori.

Cholesterol depletion reduces the level of CagA translocation and phosphorylation.

We next evaluated whether there was any difference in the levels of CagA translocation into H. pylori-infected AGS cells before and after MβCD treatment. CagA was immunoprecipitated from whole-cell lysates and analyzed by Western blotting to quantify the amount of CagA protein delivered into AGS cells. When cells were pretreated with different concentrations of MβCD (0 to 5.0 mM), the level of tyrosine-phosphorylated CagA decreased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A and B). Compared with nontreated cells, there was a significantly smaller amount of tyrosine-phosphorylated CagA when cells were treated with 5.0 mM MβCD. Thus, cholesterol depletion by MβCD that disrupted the organization of rafts also interrupted the translocation of CagA via the TFSS, leading to the reduced level of CagA phosphorylation. Upon replenishment of cholesterol, the inhibitory effect of MβCD on CagA phosphorylation was reversed (Fig. 5A and B). Together, these results suggest that the presence of sufficient cholesterol in lipid raft microdomains is required to mediate the translocation of CagA by the TFSS efficiently.

FIG. 5.

Sufficient cellular cholesterol was essential for H. pylori CagA translocation and phosphorylation. (A) AGS cells were pretreated as follows: (i) treated with various concentrations of MβCD (0, 1.0, 2.5, and 5.0 mM) and (ii) treated with 5.0 mM MβCD and replenished with cholesterol (400 μg/ml). Cells were then infected with the H. pylori 26695 wild type or ΔCagA mutant. Whole-cell lysates were immunoprecipitated for CagA, and the immunoprecipitates were subjected to Western blot analysis. Tyrosine-phosphorylated CagA was probed using mouse anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (4G10), and CagA was probed using mouse anti-CagA. Actin from whole-cell lysates was detected by using goat anti-actin antibody to ensure equal loading. (B) The level of CagA phosphorylation was evaluated by densitometric analysis. The values are means and standard deviations of four independent experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated using the paired t test (asterisk, P < 0.05). Hp, H. pylori; IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blotting; Cho, cholesterol; anti-PY, anti-phosphotyrosine antibody.

Cholesterol depletion inhibits the expression of the CagA-induced hummingbird phenotype and reduces induction of CagA-mediated IL-8.

We next tested whether cholesterol extraction that blocked CagA translocation/phosphorylation also specifically reduced CagA-induced responses by evaluating the hummingbird phenotype of AGS cells. Approximately 35% of AGS cells exhibited the hummingbird phenotype after infection, compared with the essentially normal-shaped untreated cells (Fig. 6A, first row, and Fig. 6B). With MβCD (1.0 to 5.0 mM) pretreatment, the proportion of elongated cells was reduced in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6A, second row, and Fig. 6B). The proportion of elongated cells was restored by replenishment of cholesterol (Fig. 6A and B). When cells were infected with the ΔCagA mutant, almost no cells developed into the long needlelike structure (Fig. 6A), consistent with previous results (6).

FIG. 6.

The level of cellular cholesterol influenced the CagA-induced responses of infected AGS cells. (A) The hummingbird phenotype of infected AGS cells induced by CagA was blocked by cholesterol depletion. AGS cells were pretreated with or without MβCD, which was followed by infection with wild-type H. pylori or the ΔCagA mutant, and then viewed by phase-contrast microscopy. MβCD−, without MβCD treatment; MβCD+, with 5.0 mM MβCD treatment; Cho recover+, MβCD-treated cells that were replenished with 400 μg/ml cholesterol for 1 h; WT Hp+, cells infected by wild-type H. pylori; Hp−, noninfected cells; ΔCagA+, cells infected by H. pylori ΔCagA. In each experiment, AGS cells were added to mid-logarithmic-phase bacteria at a synchronized MOI of 100 and incubated at 37°C for 6 h. Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) The proportion of elongated cells was determined from the results shown in panel A. Cho, cholesterol; Hp, H. pylori; WT, wild type. (C) Induction of IL-8 involves CagA and host cellular cholesterol. AGS cells were treated with lovastatin (0, 10, 20, and 50 μM) and infected with wild-type H. pylori (filled bars) or the ΔCagA mutant (open bars). After 6 h of infection, the level of IL-8 in the culture supernatant was determined by a standard ELISA method. The data are the means and standard deviations of at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated using Student's t test (one asterisk, P < 0.05; two asterisks, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant).

Brandt et al. previously reported that CagA expression leads to IL-8 induction via the NF-κB signaling pathway in AGS cells (13). Thus, we sought to assess whether lower levels of cellular cholesterol had any effect on IL-8 secretion in H. pylori-infected cells. In the absence of any treatment, a significantly higher level of IL-8 production was detected in cells infected with wild-type H. pylori than in cells infected with H. pylori ΔCagA (Fig. 6C), confirming the notion that CagA mediates IL-8 induction. When cells were treated with 10 μM lovastatin and then infected with wild-type H. pylori, there was no significant difference in the level of IL-8 induction between treated and untreated cells. As higher concentrations of lovastatin were added (20 and 50 μM), a significant decrease in the level of IL-8 induction was detected compared with untreated cells (P < 0.01). A similar dose-dependent reduction was seen for cells infected with H. pylori ΔCagA. These results suggest that CagA-induced IL-8 secretion was blocked by cholesterol depletion and that efficient CagA-independent IL-8 induction (57) might also require an adequate amount of cholesterol.

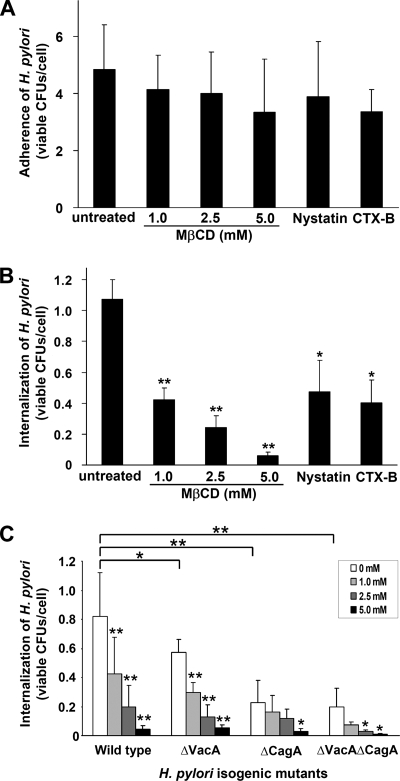

H. pylori adherence to AGS cells is not influenced by raft-disrupting agents.

We next asked whether MβCD treatment that extracted both cholesterol and GM1 influenced the level of H. pylori binding. When cells were treated with various concentrations of MβCD, interestingly, no significant decrease in the adherence of H. pylori to AGS cells was observed (Fig. 7A). We also evaluated the effect by treating cells with two other raft-disrupting agents: (i) nystatin, which complexes cholesterol and alters the structure and function of glycolipid microdomains and caveolae (4); and (ii) CTX-B, which binds to GM1 on lipid rafts (36, 62). As shown in Fig. 7A, there was no statistical difference in the levels of bacterial adherence when cells were treated with these agents.

FIG. 7.

H. pylori internalization rather than adherence to AGS cells is influenced by raft-disrupting agents. (A) Adherence of H. pylori to AGS cells was not blocked by pretreatment with MβCD, nystatin (50 μg/ml), or CTX-B (20 μg/ml). (B) Internalization of H. pylori in AGS cells was influenced by pretreatment with MβCD, nystatin (50 μg/ml), or CTX-B (20 μg/ml). (C) Surface virulence factors CagA and VacA were involved in the in vitro internalization assay. AGS cells were not treated or pretreated with MβCD (1.0, 2.5, and 5.0 mM) and then infected with wild-type H. pylori and isogenic mutants (ΔVacA, ΔCagA, and ΔVacAΔCagA). The viable bacterial uptake shown in panels B and C was determined by an in vitro gentamicin assay. The results are expressed as the number of viable CFU per cell, and the values are the means and standard deviations of at least six independent experiments. Statistical significance was calculated using Student's t test and compared to the untreated cells in panels A and B. In panel C, statistical significance was calculated for each isogenic mutant by comparison to wild-type H. pylori. A statistical evaluation of the internalization activity for infected cells before and after MβCD treatment was performed for the wild-type, ΔVacA, ΔCagA, and ΔVacAΔCagA strains. One asterisk, P < 0.05; two asterisks, P < 0.01.

As H. pylori can internalize in AGS cells, as determined by in vitro gentamicin assays (42), we tested whether cholesterol depletion influenced internalization by AGS cells. With MβCD pretreatment, there was dose-dependent inhibition of internalization of bacteria in AGS cells (P < 0.01) (Fig. 7B). Additionally, treatment with both nystatin and CTX-B resulted in significant inhibition of H. pylori internalization (P < 0.05). Collectively, these results suggest that the initial binding of H. pylori to AGS cells is largely independent of cellular rafts, whereas subsequent bacterial actions, including CagA translocation via the TFSS and internalization in AGS cells, require the presence of sufficient cellular cholesterol on rafts.

We also tested whether the CagA and VacA that were present in DRMs were engaged in the process of bacterial internalization using the AGS cultured-cell assay. Isogenic mutants (ΔVacA, ΔCagA, and ΔVacAΔCagA) were generated from 26695 by insertional mutagenesis. In vitro gentamicin assays revealed that each mutant had significantly reduced internalization activity compared with the parental strain (wild type versus ΔVacA, P < 0.03; wild type versus ΔCagA, P < 0.001; wild type versus ΔVacAΔCagA, P < 0.001) (Fig. 7C). There was no statistical difference in the levels of bacterial internalization between the ΔCagA and ΔVacAΔCagA mutants. Our results were in accordance with the findings in Petersen et al., who showed that abolishing expression of VacA or CagA led to reduced levels of H. pylori internalization activity (42). These results were also in line with the observation that two type I strains had higher levels of entry, but not adherence, than a type II isolate (54). With increasing concentrations of MβCD during pretreatment, there was a dose-dependent reduction in the level of bacterial internalization in AGS cells compared with the untreated cells for the parental wild-type strain (P < 0.01). Similar results were obtained for the ΔVacA strain. ΔCagA and ΔVacAΔCagA also showed reduced internalization activity upon MβCD pretreatment. Given the much lower internalization activity, there was less statistical significance (Fig. 7C).

DISCUSSION

Lipid rafts that contain cellular cholesterol have been shown to be utilized by VacA for binding and entry, hence exhibiting intoxication activity (23, 29, 40, 44, 46). Wunder et al. recently reported that H. pylori absorbs cellular cholesterol and transforms it into glucosylated derivatives to evade phagocytosis during infection (63). In this investigation, we showed that the delivery of CagA into host cells and subsequent CagA-induced functions require sufficient cellular cholesterol during infection. Several lines of evidence support this view: (i) cholesterol depletion reduced the level of CagA translocation and phosphorylation in infected cells; (ii) adhered bacteria and a significant portion of translocated CagA were colocalized with raft-associated molecules, GM1 and c-Src, during infection; (iii) CagA and VacA were cofractionated with DRMs and, upon cholesterol depletion, shifted to fractions of non-DRMs; and (iv) cholesterol depletion blocked the CagA-induced cellular responses, including the hummingbird phenotype and IL-8 induction. Our results therefore strongly suggest that cholesterol plays a significant role not only in VacA intoxication and immune evasion but also in delivering CagA into cells to effect actin rearrangement and other CagA-mediated responses during infection. Our data, in relation to the recent report by Kwok et al. (30), indicate that integrins are required for H. pylori adherence and for the TFSS to inject CagA into the host cells. It is also noted that integrins are raft associated (34).

Observation of the accumulation of ganglioside GM1 at the sites of bacterial uptake in infected AGS cells revealed that there is an intimate association between adhered/endocotysed bacteria and lipid rafts, as these microdomains are generally dispersed in the cell membrane. We found that bacterial adherence was largely unaffected by raft disruptors, including MβCD, nystatin, and CTX-B. In contrast, subsequent bacterial actions, including CagA translocation and bacterial internalization into AGS cells, were influenced by raft-disrupting agents. Indeed, confocal fluorescence microscopy revealed the presence of adhered bacteria with or without MβCD pretreatment on the cell surface, while endocytosed bacteria were observed only without MβCD pretreatment. These results thus suggest that the initial H. pylori-AGS contacts are independent of lipid rafts. On the other hand, CagA translocation and phosphorylation, subsequent internalization into AGS cells, and perhaps other processes rely on the utilization of lipid rafts.

Our data demonstrate that a high level of host cell plasma membrane cholesterol must be maintained on rafts for efficient TFSS-dependent CagA translocation. One hypothesis is that cholesterol might act as a ubiquitous eukaryotic “raft-associated receptor/coreceptor” that facilitates H. pylori recognition of the host cell surface and influences TFSS integration into the membrane and subsequent translocation of CagA across the membrane. This presumably provides a prominent advantage, as CagA is translocated in close proximity to the host cell targets, like c-Src, which is concentrated within cholesterol-rich microdomains for downstream signaling. It is also possible that rafts can serve as a physically rigid region, ensuring the assembly of a complete TFSS to inject CagA into host cells efficiently.

Apart from host cellular cholesterol, other determinants may be needed to facilitate H. pylori recognition and mobilization to sites of rafts or to induce movement of raft microdomains into attachment sites. Bacterial adhesion molecules, such as BabA, bind to cell surface receptors to establish the initial contact with host cells (27). Bacterium-associated VacA, which itself binds to rafts independently and induces fusion of membranes from intracellular compartments (29), may promote raft coalescence into sites of bacterial attachment. However, whether other host components are engaged in this process and how the TFSS integrates, interacts with cholesterol-rich microdomains, and controls effector translocation into a region with c-Src for downstream signaling requires further investigation.

In conclusion, in this study we obtained evidence that an adequate amount of cellular cholesterol is crucial for efficient TFSS-mediated CagA translocation and phosphorylation, as well as CagA-induced responses during H. pylori infection. Along with the utilization of cellular cholesterol for VacA intoxication and immune evasion, our data further suggest that H. pylori is able to exploit cellular cholesterol to gain an evolutionary survival advantage. Indeed, other gastrointestinal pathogens, including FimH-expressing Escherichia coli (10) and Shigella (31), have a common strategy for utilizing lipid rafts that contain cholesterol. These findings may imply that the stomach can serve as a temporary reservoir and that some bacteria are capable of invading the gastric epithelium and persisting in a quiescent state under suitable conditions, such as a high level of cellular cholesterol, and later reemerge to initiate another round of infection (3, 41). Such mechanisms may also underlie the success of H. pylori in surviving throughout human history in this unique niche (17).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Council, Taiwan (grants NSC96-3112-B-007-002, NSC96-2313-B-007-001, NSC96-3112-B-007-003, NSC95-3112-B-007-003, and NSC95-2320-B-039-051), and was partially supported by the Veterans General Hospitals University System of Taiwan Joint Research Program, Chi-Shuen Tsou's Foundation (grant VGHUST96-P6-21).

Editor: J. B. Bliska

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 April 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrami, L., and F. G. van Der Goot. 1999. Plasma membrane microdomains act as concentration platforms to facilitate intoxication by aerolysin. J. Cell Biol. 147175-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alm, R. A., and T. J. Trust. 1999. Analysis of the genetic diversity of Helicobacter pylori: the tale of two genomes. J. Mol. Med. 77834-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amieva, M. R., N. R. Salama, L. S. Tompkins, and S. Falkow. 2002. Helicobacter pylori enter and survive within multivesicular vacuoles of epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 4677-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson, H. A., Y. Chen, and L. C. Norkin. 1996. Bound simian virus 40 translocates to caveolin-enriched membrane domains, and its entry is inhibited by drugs that selectively disrupt caveolae. Mol. Biol. Cell 71825-1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asahi, M., Y. Tanaka, T. Izumi, Y. Ito, H. Naiki, D. Kersulyte, K. Tsujikawa, M. Saito, K. Sada, S. Yanagi, A. Fujikawa, M. Noda, and Y. Itokawa. 2003. Helicobacter pylori CagA containing ITAM-like sequences localized to lipid rafts negatively regulates VacA-induced signaling in vivo. Helicobacter 81-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Backert, S., S. Moese, M. Selbach, V. Brinkmann, and T. F. Meyer. 2001. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 972 of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein is essential for induction of a scattering phenotype in gastric epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 42631-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Backert, S., T. Schwarz, S. Miehlke, C. Kirsch, C. Sommer, T. Kwok, M. Gerhard, U. B. Goebel, N. Lehn, W. Koenig, and T. F. Meyer. 2004. Functional analysis of the cag pathogenicity island in Helicobacter pylori isolates from patients with gastritis, peptic ulcer, and gastric cancer. Infect. Immun. 721043-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Backert, S., E. Ziska, V. Brinkmann, U. Zimny-Arndt, A. Fauconnier, P. R. Jungblut, M. Naumann, and T. F. Meyer. 2000. Translocation of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein in gastric epithelial cells by a type IV secretion apparatus. Cell. Microbiol. 2155-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagnoli, F., L. Buti, L. Tompkins, A. Covacci, and M. R. Amieva. 2005. Helicobacter pylori CagA induces a transition from polarized to invasive phenotypes in MDCK cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10216339-16344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baorto, D. M., Z. Gao, R. Malaviya, M. L. Dustin, A. van der Merwe, D. M. Lublin, and S. N. Abraham. 1997. Survival of FimH-expressing enterobacteria in macrophages relies on glycolipid traffic. Nature 389636-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blaser, M. J., and D. E. Berg. 2001. Helicobacter pylori genetic diversity and risk of human disease. J. Clin. Investig. 107767-773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourzac, K. M., and K. Guillemin. 2005. Helicobacter pylori-host cell interactions mediated by type IV secretion. Cell. Microbiol. 7911-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandt, S., T. Kwok, R. Hartig, W. Konig, and S. Backert. 2005. NF-κB activation and potentiation of proinflammatory responses by the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1029300-9305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown, D. A., and E. London. 2000. Structure and function of sphingolipid- and cholesterol-rich membrane rafts. J. Biol. Chem. 27517221-17224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Censini, S., C. Lange, Z. Xiang, J. E. Crabtree, P. Ghiara, M. Borodovsky, R. Rappuoli, and A. Covacci. 1996. cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9314648-14653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung, C. S., C. Y. Huang, and W. Chang. 2005. Vaccinia virus penetration requires cholesterol and results in specific viral envelope proteins associated with lipid rafts. J. Virol. 791623-1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Covacci, A., J. L. Telford, G. Del Giudice, J. Parsonnet, and R. Rappuoli. 1999. Helicobacter pylori virulence and genetic geography. Science 2841328-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cover, T. L., and S. R. Blanke. 2005. Helicobacter pylori VacA, a paradigm for toxin multifunctionality. Nat. Rev. 3320-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crabtree, J. E., A. Covacci, S. M. Farmery, Z. Xiang, D. S. Tompkins, S. Perry, I. J. Lindley, and R. Rappuoli. 1995. Helicobacter pylori induced interleukin-8 expression in gastric epithelial cells is associated with CagA positive phenotype. J. Clin. Pathol. 4841-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dykstra, M., A. Cherukuri, H. W. Sohn, S. J. Tzeng, and S. K. Pierce. 2003. Location is everything: lipid rafts and immune cell signaling. Annu. Rev. Immun. 21457-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Endo, A. 1981. 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors. Methods Enzymol. 72684-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer, W., J. Puls, R. Buhrdorf, B. Gebert, S. Odenbreit, and R. Haas. 2001. Systematic mutagenesis of the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island: essential genes for CagA translocation in host cells and induction of interleukin-8. Mol. Microbiol. 421337-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gauthier, N. C., V. Ricci, P. Gounon, A. Doye, M. Tauc, P. Poujeol, and P. Boquet. 2004. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins and actin cytoskeleton modulate chloride transport by channels formed by the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin VacA in HeLa cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2799481-9489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gryczan, T. J., G. Grandi, J. Hahn, R. Grandi, and D. Dubnau. 1980. Conformational alteration of mRNA structure and the posttranscriptional regulation of erythromycin-induced drug resistance. Nucleic Acids Res. 86081-6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higashi, H., K. Yokoyama, Y. Fujii, S. Ren, H. Yuasa, I. Saadat, N. Murata-Kamiya, T. Azuma, and M. Hatakeyama. 2005. EPIYA motif is a membrane-targeting signal of Helicobacter pylori virulence factor CagA in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 28023130-23137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikonen, E. 2001. Roles of lipid rafts in membrane transport. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13470-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ilver, D., A. Arnqvist, J. Ogren, I. M. Frick, D. Kersulyte, E. T. Incecik, D. E. Berg, A. Covacci, L. Engstrand, and T. Boren. 1998. Helicobacter pylori adhesin binding fucosylated histo-blood group antigens revealed by retagging. Science 279373-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuo, C. H., S. K. Poon, Y. C. Su, R. Su, C. S. Chang, and W. C. Wang. 1999. Heterogeneous Helicobacter pylori isolates from H. pylori-infected couples in Taiwan. J. Infect. Dis. 1802064-2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuo, C. H., and W. C. Wang. 2003. Binding and internalization of Helicobacter pylori VacA via cellular lipid rafts in epithelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 303640-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwok, T., D. Zabler, S. Urman, M. Rohde, R. Hartig, S. Wessler, R. Misselwitz, J. Berger, N. Sewald, W. Konig, and S. Backert. 2007. Helicobacter exploits integrin for type IV secretion and kinase activation. Nature 449862-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lafont, F., G. Tran Van Nhieu, K. Hanada, P. Sansonetti, and F. G. van der Goot. 2002. Initial steps of Shigella infection depend on the cholesterol/sphingolipid raft-mediated CD44-IpaB interaction. EMBO J. 214449-4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai, C. H., C. H. Kuo, P. Y. Chen, S. K. Poon, C. S. Chang, and W. C. Wang. 2006. Association of antibiotic resistance and higher internalization activity in resistant Helicobacter pylori isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57466-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai, C. H., C. H. Kuo, Y. C. Chen, F. Y. Chao, S. K. Poon, C. S. Chang, and W. C. Wang. 2002. High prevalence of cagA- and babA2-positive Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates in Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 403860-3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leitinger, B., and N. Hogg. 2002. The involvement of lipid rafts in the regulation of integrin function. J. Cell Sci. 115963-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall, B. 2002. Helicobacter pylori: 20 years on. Clin. Med. 2147-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naroeni, A., and F. Porte. 2002. Role of cholesterol and the ganglioside GM1 in entry and short-term survival of Brucella suis in murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 701640-1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Odenbreit, S., J. Puls, B. Sedlmaier, E. Gerland, W. Fischer, and R. Haas. 2000. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science 2871497-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orlandi, P. A., and P. H. Fishman. 1998. Filipin-dependent inhibition of cholera toxin: evidence for toxin internalization and activation through caveolae-like domains. J. Cell Biol. 141905-915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parsonnet, J. 1998. Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 12185-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel, H. K., D. C. Willhite, R. M. Patel, D. Ye, C. L. Williams, E. M. Torres, K. B. Marty, R. A. MacDonald, and S. R. Blanke. 2002. Plasma membrane cholesterol modulates cellular vacuolation induced by the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. Infect. Immun. 704112-4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petersen, A. M., and K. A. Krogfelt. 2003. Helicobacter pylori: an invading microorganism? A review. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 36117-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petersen, A. M., K. Sorensen, J. Blom, and K. A. Krogfelt. 2001. Reduced intracellular survival of Helicobacter pylori vacA mutants in comparison with their wild-types indicates the role of VacA in pathogenesis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 30103-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poppe, M., S. M. Feller, G. Romer, and S. Wessler. 2007. Phosphorylation of Helicobacter pylori CagA by c-Abl leads to cell motility. Oncogene 263462-3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ricci, V., A. Galmiche, A. Doye, V. Necchi, E. Solcia, and P. Boquet. 2000. High cell sensitivity to Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin depends on a GPI-anchored protein and is not blocked by inhibition of the clathrin-mediated pathway of endocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 113897-3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rose, R. E. 1988. The nucleotide sequence of pACYC177. Nucleic Acids Res. 16356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schraw, W., Y. Li, M. S. McClain, F. G. Van Der Goot, and T. L. Cover. 2002. Association of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin (VacA) with lipid rafts. J. Biol. Chem. 27734642-34650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Segal, E. D., J. Cha, J. Lo, S. Falkow, and L. S. Tompkins. 1999. Altered states: involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9614559-14564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Selbach, M., S. Moese, C. R. Hauck, T. F. Meyer, and S. Backert. 2002. Src is the kinase of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2776775-6778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharma, S. A., M. K. Tummuru, M. J. Blaser, and L. D. Kerr. 1998. Activation of IL-8 gene expression by Helicobacter pylori is regulated by transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa B in gastric epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 1602401-2407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shin, J. S., Z. Gao, and S. N. Abraham. 2000. Involvement of cellular caveolae in bacterial entry into mast cells. Science 289785-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simons, K., and E. Ikonen. 1997. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature 387569-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simons, K., and D. Toomre. 2000. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 131-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stein, M., R. Rappuoli, and A. Covacci. 2000. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the Helicobacter pylori CagA antigen after cag-driven host cell translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 971263-1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Su, B., S. Johansson, M. Fallman, M. Patarroyo, M. Granstrom, and S. Normark. 1999. Signal transduction-mediated adherence and entry of Helicobacter pylori into cultured cells. Gastroenterology 117595-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tomb, J. F., O. White, A. R. Kerlavage, R. A. Clayton, G. G. Sutton, R. D. Fleischmann, K. A. Ketchum, H. P. Klenk, S. Gill, B. A. Dougherty, K. Nelson, J. Quackenbush, L. Zhou, E. F. Kirkness, S. Peterson, B. Loftus, D. Richardson, R. Dodson, H. G. Khalak, A. Glodek, K. McKenney, L. M. Fitzegerald, N. Lee, M. D. Adams, E. K. Hickey, D. E. Berg, J. D. Gocayne, T. R. Utterback, J. D. Peterson, J. M. Kelley, M. D. Cotton, J. M. Weidman, C. Fujii, C. Bowman, L. Watthey, E. Wallin, W. S. Hayes, M. Borodovsky, P. D. Karp, H. O. Smith, C. M. Fraser, and J. C. Venter. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 388539-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Echten, G., and K. Sandhoff. 1993. Ganglioside metabolism. Enzymology, topology, and regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2685341-5344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Viala, J., C. Chaput, I. G. Boneca, A. Cardona, S. E. Girardin, A. P. Moran, R. Athman, S. Memet, M. R. Huerre, A. J. Coyle, P. S. DiStefano, P. J. Sansonetti, A. Labigne, J. Bertin, D. J. Philpott, and R. L. Ferrero. 2004. Nod1 responds to peptidoglycan delivered by the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island. Nat. Immunol. 51166-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang, W. C., K. Zinn, and P. J. Bjorkman. 1993. Expression and structural studies of fasciclin I, an insect cell adhesion molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 2681448-1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang, Y., K. P. Roos, and D. E. Taylor. 1993. Transformation of Helicobacter pylori by chromosomal metronidazole resistance and by a plasmid with a selectable chloramphenicol resistance marker. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1392485-2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang, Y., and D. E. Taylor. 1990. Chloramphenicol resistance in Campylobacter coli: nucleotide sequence, expression, and cloning vector construction. Gene 9423-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Warren, J. R. 1983. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet i1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wolf, A. A., M. G. Jobling, S. Wimer-Mackin, M. Ferguson-Maltzman, J. L. Madara, R. K. Holmes, and W. I. Lencer. 1998. Ganglioside structure dictates signal transduction by cholera toxin and association with caveolae-like membrane domains in polarized epithelia. J. Cell Biol. 141917-927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wunder, C., Y. Churin, F. Winau, D. Warnecke, M. Vieth, B. Lindner, U. Zahringer, H. J. Mollenkopf, E. Heinz, and T. F. Meyer. 2006. Cholesterol glucosylation promotes immune evasion by Helicobacter pylori. Nat. Med. 121030-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yamaoka, Y., D. H. Kwon, and D. Y. Graham. 2000. A Mr 34,000 proinflammatory outer membrane protein (oipA) of Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 977533-7538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang, J. C., T. H. Wang, H. J. Wang, C. H. Kuo, J. T. Wang, and W. C. Wang. 1997. Genetic analysis of the cytotoxin-associated gene and the vacuolating toxin gene in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from Taiwanese patients. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 921316-1321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zeidel, M. L. 1996. Low permeabilities of apical membranes of barrier epithelia: what makes watertight membranes watertight? Am. J. Physiol. 271F243-F245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]