Abstract

“TKO” is an expression vector that knocks out the activity of a transcription factor in vivo under genetic control. We describe a successful test of this concept that used a sea urchin transcription factor of known function, P3A2, as the target. The TKO cassette employs modular cis-regulatory elements to express an encoded single-chain antibody that prevents the P3A2 protein from binding DNA in vivo. In normal development, one of the functions of the P3A2 transcription factor is to repress directly the expression of the CyIIIa cytoskeletal actin gene outside the aboral ectoderm of the embryo. Ectopic expression in oral ectoderm occurs if P3A2 sites are deleted from CyIIIa expression constructs, and we show here that introduction of an αP3A2⋅TKO expression cassette causes exactly the same ectopic oral expression of a coinjected wild-type CyIIIa construct. Furthermore, the αP3A2⋅TKO cassette derepresses the endogenous CyIIIa gene in the oral ectoderm and in the endoderm. αP3A2⋅TKO thus abrogates the function of the endogenous SpP3A2 transcription factor with respect to spatial repression of the CyIIIa gene. Widespread expression of αP3A2⋅TKO in the endoderm has the additional lethal effect of disrupting morphogenesis of the archenteron, revealing a previously unsuspected function of SpP3A2 in endoderm development. In principle, TKO technology could be utilized for spatially and temporally controlled blockade of any transcription factor in any biological system amenable to gene transfer.

In this communication we describe a means of blocking a specific gene regulatory interaction in living sea urchin embryos. Sea urchins have a relatively simple process of embryogenesis, and an efficient and straightforward method of gene transfer has been developed, affording the opportunity to introduce expression constructs into thousands of eggs per day. Sea urchin eggs and embryos have thus emerged as a major experimental system for analysis of developmental cis-regulatory functions (1–3). Quantitative temporal and spatial patterns of reporter-gene expression can be conveniently assessed (e.g., refs. 3–5). Many relevant sea urchin transcription factors have been purified by using affinity chromatography after identification of their cis-regulatory target sites and subsequently have been cloned (6). Antisense oligonucleotides can be used to destroy maternal mRNAs encoding transcription factors; however (7), there has been no general or direct way to examine the function of specific transcription factors in sea urchin embryos by blocking their activity in vivo. This would afford the opportunity to compare the effects of canceling transcription factor activity with the effects of mutations of the relevant target sites in an expression vector (8). More generally, it would provide a means of determining downstream functions of the targeted factor.

Here we demonstrate the functional blockade of a transcription factor that had previously been shown to be responsible for spatial control of a developmentally regulated sea urchin embryo gene. This was accomplished by introducing into fertilized eggs an expression construct that encodes a single-chain antibody that binds to the factor and prevents it from forming complexes with its DNA target sites. We term this a “TKO” (Transcription factor Knock Out) vector.

The TKO vector described herein was designed to attack the SpP3A2 transcription factor (9), the initial member of a small family of transcription factors that now includes Drosophila erect wing (10), chicken IBR/F (11), and human NRF-1 (12). P3A2 was cloned and characterized (9, 13) after identification of two of its target sites in the cis-regulatory element of the CyIIIa cytoskeletal actin gene, which were found to be required for correct spatial expression of this gene. This gene is normally expressed only in aboral ectoderm lineages beginning early in development. CyIIIa⋅CAT expression constructs reproduce the aboral expression of the parent gene, but if either of the P3A2 sites in the wild-type construct is destroyed, expression spreads dramatically to the oral ectoderm (14). Similarly, if the endogenous P3A2 factor is titrated away from the CyIIIa⋅CAT expression construct by cointroduction of excess target-site, ectopic oral ectoderm expression is also observed (15). Our objectives in this work were threefold: first, to develop a TKO vector that would effectively sequester endogenous P3A2 transcription factor (αP3A2⋅TKO), the functionality of which could be assayed by determining its effects on spatial expression of CyIIIa⋅CAT; second, to determine whether we could affect the expression of the endogenous CyIIIa gene during embryonic development; and third, to look for any other phenotypes in αP3A2⋅TKO embryos that may indicate additional embryonic functions of the P3A2 transcription factor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA-Binding Inhibition Assays.

P3A2 DNA-binding electrophoretic mobility-shift assays (EMSAs) were performed as previously described by Calzone et al. (9) using the P3A2 binding site (top strand: 5′-GATCTTTTCGGCTTCTGCGCACACCCCACGCGCATGGGC-3′) and crude nuclear extracts. Inhibition assays were performed by incubating P3A2 DNA binding reactions with serial dilutions of supernatant from hybridoma-producing αP3A2 mAbs. The αP3A2 mAbs were created in the Caltech Monoclonal Antibody Facility (16). Hybridoma ascites fluid and bacterial extracts containing the αP3A2 sites were similarly assayed. In these assays, inhibition of P3A2–DNA complex formation was estimated quantitatively as described in Fig. 1.

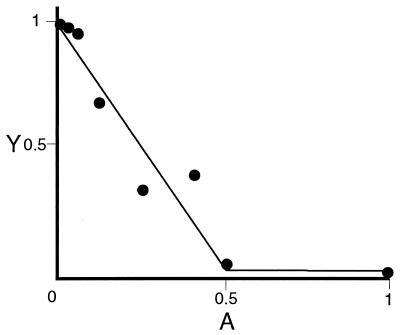

Figure 1.

Measurement of inhibitory activity of mAb with respect to specific P3A2–DNA complex formation. Relative occupancy of oligonucleotide probe (Y) is plotted against an antibody dilution series (A). The intercept, Y0 (here Y0 = 0.78 of total probe in the reaction) represents the probe occupancy in the absence of antibody (A = 0). The inhibitory activity is quantitatively estimated as the value of kA, the slope; here, kA = 1.26 × 1010 M−1. The data are fit to the function Y = αkA·A + Y0 (Eq. 1). Here Y is occupancy of oligonucleotide probe; i.e., where PD(A) dilution (antibody concentration was measured after purification of the antibody from the hybridoma ascites fluid) and D0 is concentration of total probe in the reaction: Y = PDA/D0. In Eq. 1, α = −2P0, where P0 is the molar quantity of P3A2 transcription factor in the reaction; in these experiments, P0 ranged from 2 to 5 × 10−11 M. kA is defined as the equilibrium constant for the reaction of a mAb molecule with two P3A2 molecules, i.e., kA = AP2/A · P02. Eq. (1) follows from the assumption that all P3A2 molecules will be in complex with either the antibody or the DNA probe and that the P3A2–DNA reaction is bimolecular, i.e., PD(A) = kDP(A) · D(A), where P(A) and D(A) are the molar concentrations of the free P3A2 protein and the DNA probe at given antibody dilutions.

Production of the Single-Chain Anti-P3A2 Antibody.

Hybridoma poly(A) RNA was purified by using the Stratagene RNA Isolation kit and Dynal (Great Neck, NY) oligo(dT) beads as described by the manufacturers. Heavy- and light-chain cDNAs were isolated from hybridoma cDNA libraries constructed by using the Stratagene Uni-Zap vector system. Subsequently, the variable heavy- and light-chain coding regions of these cDNAs were fused in-frame (separated by an encoded flexible Gly/Ser linker) into the pCANTAB 5 vector by using the expression module of the Pharmacia single-chain antibody (scFv) system.

Construction of TKO and Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) Expression Cassettes.

The TKO cassette was constructed in steps. First, the simian virus (SV)40 large T 3′ untranslated intron, transcriptional attenuation, and polyadenylation signals isolated from the pNL vector (17) were cloned into the EcoRI site of pBluescript II KS− [BSpoly(A) construct]. Second, the coding region of the αP3A2 scFv was recovered from the positive pCANTAB 5 phagemid by PCR, using either the Ab1 5′ primer to make the TKO expression cassette or the Ab3 5′ primer to make a missense control cassette. Primers were as follows: Ab1, 5′-GGGCGGCCGCCACCATGGCCACCGCCCCAAAGAAGAAGCGTAAGGCCCAGGTGAAACTGCAG-3′. The italicized base is deleted in primer Ab3 5′; otherwise, primers Ab1 5′ and Ab3 5′ are identical. Sequences encoding a nuclear localization site following the ATG site: Ab-reverse, 5′-GGGACTAGTCTTGTCGTCGTCGTCCTTGTAGTCCACCGGCGCACCTGCGGC-3′. Standard PCR was carried out in 100-μl volumes containing 50 pmol of each primer, 1× Deep Vent buffer (New England Biolabs), 2 μmol of dNTPs, ≈10 ng of target sequence, and sterile H2O. Reactions were heated to 94°C for 2 min, 5 units of Deep Vent polymerase was added (New England Biolabs), and the mixture was cycled 25 times (30 sec, 94°C; 30 sec, 60°C; 60 sec, 72°C) in a Perkin–Elmer 9600 thermocycler. The PCR products were digested with NotI, purified, and ligated into the BSpoly(A)1 vector. The final TKO and missense cassettes were made by ligating either the cis-regulatory element (18) of the SpH2b early histone gene into the SacII site or the SpHE hatching enzyme gene cis-regulatory element (a gift from L. Angerer, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY; see ref. 19) into the SacI site of the respective TKO and missense constructs. The histone gene regulatory sequences were amplified from the SpH2b clone (18) with the following oligonucleotide primers: H2b5, 5′-CCCGCGGCCGCGGTCTCAAAATATGATTGGCAGCTTAATTTGG-3′ and H2b3, 5′-CCCCCGCGGGATGATTGTGATTCTCACGAATGC-3′. The hatching enzyme gene regulatory sequence was amplified from the parent SpHE-pNL clone by using HE5: 5′-CCCCCGCGGAAGCTTGTTTTGATTGGTTTGTTTGG-3′ and HE3: 5′-CCCCCGCGGGATGATAAGAAGTGATAATGATTTTC-3′. The pCANTAB5 anti-P3A2 scFv and TKO inserts were sequenced in an Applied Biosystems 373 sequencer. TKO and αP3A2⋅TKOmis (missense) plasmids were linearized with ClaI for microinjection. A pHE/GFP expression vector was constructed by amplifying the SpHE regulatory element with primers HESI5, 5′-CCCGAGCTCAAGCTTGTTTTGATTGGTTTGTTTGG-3′ and HE3, 5′-CCCGAGCTCGATGATAAGAAGTGATAATGATTTTC-3′ and ligating the product into the GFP expression vector pGL3-Basic (5). The resulting plasmid was linearized with KpnI for microinjection.

Microinjection, Whole-Mount in Situ Hybridization, and Fluorescence Microscopy.

Microinjection and culture of Strongylocentrotus purpuratus embryos were performed essentially as described (14). However, when multiple constructs were coinjected, we maintained the total amount of DNA injected at a constant level by proportionately lowering the amount of carrier DNA. Detection of endogenous CyIIIa expression by whole-mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) was carried out following the protocol of Ransick et al. (24) with the following modifications: The fixation step was lengthened to 20 min and the probe concentration was raised to 0.4 ng/μl. The CyIIIa antisense probe was generated by in vitro transcription from the T7 promoter of the CyIIIa–HgaI vector that had been digested with PvuII. This generates a digoxigenin-labeled probe containing 147 bases of the CyIIIa, 3′ untranslated region, and an 873-bp tail of pBluescript II SK− (procedure of David G.-W.Wang, personal communication). Fluorescence microscopy, sorting, and WMISH of GFP-injected embryos were performed as described (5).

RESULTS

αP3A2 mAb and αP3A2⋅TKO Construct.

The TKO expression construct was designed to express, translate, and transport an anti-P3A2 reagent into the nucleus so as to inhibit P3A2 from carrying out its developmental regulatory functions in vivo. A set of αP3A2 mAbs was generated against the full-length P3A2 protein. These were screened for their ability to inhibit this protein from binding to its target DNA sequence by adding them to gel-shift reactions at increasing dilutions. Inhibitory activity was measured quantitatively as described in Fig. 1. Inhibition constants were determined for 12 different hybridoma subclones. mAb 7B12/2E7 displayed the strongest inhibitory effects on P3A2 DNA binding and was chosen as the basis for the αP3A2⋅TKO vector. The same mAb was used for an extensive series of measurements of P3A2 prevalence throughout embryological development (16). The specificity of this antibody was confirmed by the observation that it reacted with only a single molecular species of the known size of the P3A2 transcription factor in total nuclear extracts from all stages of development as well as in total egg lysate (Fig. 1 of ref. 16).

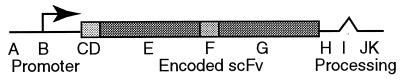

To build the αP3A2⋅TKO vector, the mRNA was extracted from 7B12/2E7 hybridoma cells, and by using the universal IgG primers amplified DNAs encoding the heavy-chain and light-chain V-regions were cloned in-frame into the Pharmacia pCANTAB vector surrounding a flexible Gly/Ser linker. Thus, a construct encoding a single-chain antibody was produced. Gel-shift inhibition assays were repeated to test the inhibitory activity of the αP3A2 scFv, which was extracted for this purpose from bacteria expressing the pCANTAB vector. Its activity was found to be quantitatively equivalent to that of the starting mAb. As described in Materials and Methods, the αP3A2 scFv was then incorporated into an expression cassette, the organization of which is summarized in Fig. 2. In addition to the scFv itself, the major features of the αP3A2⋅TKO construct are: (i) a nuclear localization site intended to increase the concentration of the scFv in the nucleus relative to that of the endogenous nuclear P3A2 factor; (ii) simian virus (SV)40 intron, 3′ trailer, termination, and poly(A) addition sites, features that are conventionally used in most sea urchin gene-transfer vectors; and (iii) a cis-regulatory control element. This last design feature, in principle, permits expression of the TKO vector to be targeted to any domain of the embryo for which a cis-regulatory element is available. However, in the present experiments we utilized instead ubiquitously, or nearly ubiquitously, active cis-regulatory elements derived from a histone H2b gene (18) and from a hatching enzyme gene (19). Stable incorporation of exogenous DNA in sea urchin embryo blastomeres is mosaic, although entirely random with respect to lineage (20), and therefore embryos are obtained that have incorporated the exogenous DNA into every possible spatial domain. In some of the experiments that follow, the αP3A2⋅TKO vector was coinjected with a GFP reporter under control of the same cis-regulatory element, so that the particular cells incorporating the αP3A2⋅TKO construct could be identified visually by GFP expression following the procedures of Arnone et al. (5). Thus, we could examine embryos in which the construct was present in endoderm, aboral ectoderm, or oral ectoderm, as desired.

Figure 2.

The TKO expression cassette. Histone 2b or hatching enzyme cis-regulatory elements (A) employed in the cassette are modular and can easily be exchanged with any other regulatory sequence. The start of transcription (B) is set to be at least 20 bp upstream of a canonical Kozak ATG (C) and a nuclear localization sequence (D) that are best fit to sea urchin initiators and codon usage. The heavy- (E) and light-chain (G) variable regions of the anti-P3A2 scFv are separated by an encoded flexible Gly/Ser linker (F). To process, stabilize, and terminate the TKO transcripts, we inserted the SV40 large T 3′ intron (I), polyadenylation (J), and transcriptional termination (K) sequences after the stop codon (H).

αP3A2⋅TKO Effects on Spatial Expression of a Wild-Type CyIIIa⋅CAT Construct.

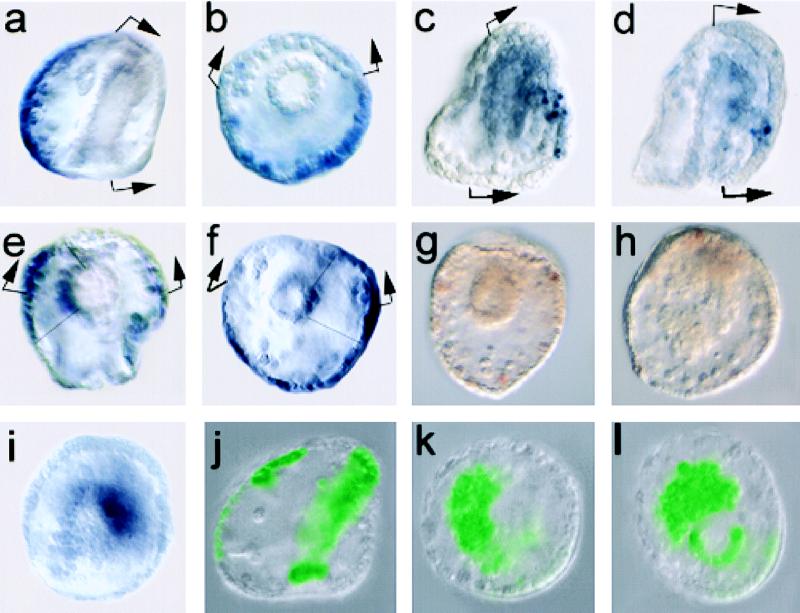

When CyIIIa⋅CAT constructs lacking the two known P3A2 target sites are injected into eggs, ectopic oral ectoderm expression is observed in an average of 34% of stained embryos (14). Because this is statistically equivalent to the percentage of embryos that incorporate exogenous DNA into oral ectoderm founder cells, it follows that essentially all oral ectoderm cells will express the CyIIIa⋅CAT construct if interactions with the P3A2 repressor are obviated by deletion. In the CyIIIa⋅CAT experiments summarized in Table 1, αP3A2⋅TKO or a missense frame shift control differing from αP3A2⋅TKO by deletion of only 1 bp were coinjected with wild-type CyIIIa⋅CAT (14). Wild-type CyIIIa⋅CAT and ΔP3A2⋅HF, the CyIIIa⋅CAT construct lacking the two P3A2 sites, were injected at the same time as the TKO constructs and performed as reported (14). When coinjected with wild-type CyIIIa⋅CAT, the missense αP3A2⋅TKO had no effect (2% oral expression). However, a remarkable result was obtained when wild-type CyIIIa⋅CAT was coinjected with αP3A2⋅TKO: 26% of stained embryos now displayed oral ectoderm expression, as illustrated in the example reproduced in Fig. 3 c and d. The 26% value could represent a slight underestimate of αP3A2⋅TKO effects or CyIIIa⋅CAT expression because in these experiments only morphologically normal stained embryos were counted, and as we discuss below, a significant fraction of embryos receiving αP3A2⋅TKO develop abnormally. In any case, the results are those predicted if the αP3A2⋅TKO vector effectively sequesters the endogenous P3A2 factor, thus preventing its interaction with the CyIIIa⋅CAT regulatory target sites. That is, as Table 1 shows, the fraction of ectopically expressing embryos is about the same as when P3A2–CyIIIa⋅CAT interactions are instead prevented by deletion of these target sites.

Table 1.

Effect of αP3A2⋅TKO and control constructs on CyIIIa⋅CAT and CyIIIa expression

Figure 3.

Effects of αP3A2⋅TKO on expression of CyIIIa⋅CAT, endogenous CyIIIa, and the lethal embryonic phenotype. In a–f, the H2b cis-regulatory element was used to drive expression of the injected TKO constructs, and in g–l, the hatching enzyme cis-regulatory element was used (see Materials and Methods). (a, b) Endogenous CyIIIa expression monitored by WMISH using an antisense CyIIIa probe (see Materials and Methods). (a) Embryo viewed laterally, oral side to the right; here and in following panels the arrows bracket the oral ectoderm where neither CyIIIa nor wild-type CyIIIa⋅CAT expression occurs. (b) Anal view, oral side to the top. (c, d) CyIIIa⋅CAT coinjected with αP3A2⋅TKO, driven by the H2b cis-regulatory element, lateral views. Clones of cells expressing CAT mRNA in the oral ectoderm are displayed by using WMISH. As observed when the P3A2 sites are deleted (14), these injections produce embryos displaying normal patterns of aboral ectoderm expression (i.e., embryos in which the exogenous DNA resides in the aboral ectoderm); embryos displaying both normal and ectopic oral ectoderm expression; and embryos displaying oral expression only (i.e., the exogenous DNA is only in oral ectoderm lineages); only the latter are illustrated here. (e, f) Effects of αP3A2⋅TKO on endogenous CyIIIa gene expression, monitored as in a and b. Both embryos are shown from the blastopore, and both display ectopic oral staining as well as staining in clones of archenteron cells in addition to aboral ectoderm expression. (g) Pluteus-stage (72-hr) embryo viewed from anal side. This embryo bears the αP3A2⋅TKOmis construct and is normal in morphology. (h) Gastrulation-defective phenotype at 72 hr caused by injection of the αP3A2⋅TKO construct. (i) Gastrulation-defective embryo at 48 hr viewed from blastopore, in which Endo16 transcripts are displayed by using WMISH. (j) Normal 48-hr embryo viewed laterally and bearing GFP-expressing clones of exogenous DNA in aboral ectoderm and archenteron. These clones also include the αP3A2⋅TKOmis control construct. (k, l) Gastrulation-defective embryos as in j, but bearing αP3A2⋅TKO construct present in large endodermal clones.

We note here that coinjection of the anti-P3A2 antibody protein into eggs together with CyIIIa⋅CAT also led to ectopic oral expression of the CyIIIa⋅CAT reporter (C. Kirchhamer and E.H.D., unpublished results). These effects were not observed when an irrelevant antibody was injected. However, this approach can be applied only to early embryos; furthermore, the αP3A2 and the control IgG caused lethal arrest of development in an unacceptably large fraction of embryos.

αP3A2⋅TKO Effects on Spatial Expression of the Endogenous CyIIIa Gene.

The foregoing results confirm the role of the P3A2 transcription factor as a spatial repressor of CyIIIa⋅CAT expression and raise the question whether the endogenous gene could be similarly affected by αP3A2⋅TKO. This was not obvious a priori, because we had found earlier that the stability of endogenous CyIIIa regulatory complexes exceeds that of the equivalent CyIIIa⋅CAT complexes: thus, in vivo competition with excess target sites for a number of CyIIIa factors stoichiometrically reduced expression of exogenous CyIIIa⋅CAT, whereas expression of the endogenous CyIIIa gene was unaffected in the same embryos (22).

The normal aboral ectoderm expression of the endogenous CyIIIa gene is displayed by WMISH in Fig. 3 a and b. When eggs were injected with αP3A2⋅TKO and endogenous CyIIIa expression was similarly monitored, ectopic expression of the endogenous gene was observed. As summarized in Table 1, 27% of these embryos display clear expression in clones of oral ectoderm, and frequently in limited clones of gut cells as well. Examples are reproduced in Fig. 3 e and f. Three embryos that displayed ectopic expression in the missense control were also found (Table 1). Because the endogenous CyIIIa gene is never expressed erroneously, the single base mutation that distinguishes αP3A2⋅TKOmis from αP3A2⋅TKO might not have entirely prevented synthesis of a functional TKO product. For example, a partially functional protein might have been generated by use of a downstream ATG. In any case, the percentage of ectopic oral expression observed in the αP3A2⋅TKO sample is very similar to that seen with either the mutated CyIIIa reporter lacking P3A2 sites (14) or in the coinjections of αP3A2⋅TKO and wild-type CyIIIa reporters (Table 1). This is as expected, because ectopic oral expression depends on clonal incorporation of the αP3A2⋅TKO construct in oral ectoderm cells in all three experiments.

A Specific αP3A2⋅TKO Embryonic Phenotype.

Embryos developing from eggs injected with αP3A2⋅TKO display a specific lethal phenotype. This occurs in a relatively high fraction of embryos, 44% in the experiment tabulated in Table 2, although in other experiments somewhat more modest frequencies of 20–30% were recorded. The αP3A2⋅TKOmis control resulted in only 5% abnormal embryos (Table 2). This phenotype is best described as a failure to form a complete archenteron, caused by a disorganization of the endoderm. Fig. 3g shows a normal 72-hr prism-stage embryo that developed from an egg that had been injected with the missense control construct, whereas the embryo in Fig. 3h displays the αP3A2⋅TKO phenotype. This embryo has not completed gastrulation. Its endoderm consists of a pile of nonadherent cells, and the form of the embryo is round rather than triangular. The secondary mesoderm appears unaffected, however. Such embryos appear to develop normally up to gastrulation. The implication is that P3A2 transcription factor is necessary for morphogenesis of the archenteron, a previously unknown function.

Table 2.

αP3A2⋅TKO effect on embryo development

| Construct | Embryos, no. tested | Gastrulation-defective, % |

|---|---|---|

| αP3A2⋅TKO | 419 | 44 |

| αP3A2⋅TKOmis | 345 | 5 |

To further investigate the role of the P3A2 transcription factor in archenteron formation, we performed a series of coinjection experiments making use of GFP as a marker to determine location of the αP3A2⋅TKO construct in the experimental embryos. GFP expression constructs can be used to determine the mosaic expression domain of a coinjected construct if both constructs are driven by the same cis-regulatory elements, because shortly after injection the exogenous DNAs are all ligated together into a concatenate and are then incorporated into the same blastomeres (5). In these experiments, the hatching enzyme cis-regulatory element was used to drive both the GFP and αP3A2⋅TKO constructs. Results are listed in Table 3. Significantly, all of the embryos bearing αP3A2⋅TKO that failed to gastrulate express the GFP marker in the endoderm (89 of 89), and less than 10% of the set of embryos in which GFP is expressed in the endoderm develop normally. All of those that do are distinguished by small GFP clone sizes (not shown). On the other hand, most of the 48% of the embryos injected with the missense control that contained endodermal clones developed normally, even though these clones were often quite large. An example is shown in Fig. 3j. Embryos bearing αP3A2⋅TKO that failed to gastrulate and that contained the exogenous DNA in the endoderm are illustrated in Fig. 3 k and l. The disorganized endoderm cells in these embryos retain their endodermal state of specification; that is, they continue to express the Endo16 marker (2, 23, 24), as shown, for example, in Fig. 3i. A few embryos in the missense control experiment also showed gastrulation defects (Table 3), and all of these contained large endodermal clones. This result again supports a weak expression of an αP3A2⋅TKO activity because of override of the frameshift, as considered above.

Table 3.

Expression of GFP in αP3A2⋅TKO and α3PA2⋅TKOmis embryos

| Construct | Phenotype | Embryos, no. tested | Endomesoderm, % | Ectoderm, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| αP3A2⋅TKO | Normal | 77 | 9 | 95 |

| αP3A2⋅TKO | GD | 89 | 100 | 73 |

| αP3A2⋅TKOmis | Normal | 186 | 48 | 78 |

| αP3A2⋅TKOmis | GD | 15 | 100 | 73 |

GD, gastrulation defective.

To explore further the relation between location of clonal incorporation and occurrence of the gastrulation phenotype, we carried out the experiment summarized in Table 4. Embryos bearing αP3A2⋅TKO plus GFP constructs were sorted according to the locus of incorporation of the expression constructs, and CyIIIa expression was then monitored by WMISH in the sorted samples. Table 4 shows that the locus of incorporation correlates perfectly with the effect of αP3A2⋅TKO on CyIIIa expression. All embryos selected for large endoderm clones again were gastrulation-defective (19 of 19), whereas 9 of 10 embryos that contained large oral-ectoderm clones displayed ectopic expression of CyIIIa in the oral ectoderm. Conversely, all embryos bearing large aboral ectoderm clones displayed normal CyIIIa expression.

Table 4.

CyIIIa transcripts in presorted embryos bearing GFP and TKO (αP3A2⋅TKO) expression constructs

| Phenotype | GFP sorted | Endomesoderm | Oral | Aboral |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GD | Endoderm | 19/19 | ND | ND |

| Normal | Oral | 0 | 9/10 | 10/10 |

| Normal | Aboral | 0 | 0 | 9/9 |

GD, gastrulation-defective; ND, not done. Oral and aboral ectodermal domains are difficult to distinguish in gastrulation-defective embryos, because of their abnormally rounded form (see Fig. 3h, for example).

It may be concluded from these experiments that the function of P3A2 in archenteron morphogenesis is cell-autonomous, i.e., that the factor is needed in the archenteron cells themselves. Similarly, we confirm that the function of P3A2 in oral ectoderm as a spatial repressor of CyIIIa transcription is also autonomous, as proposed earlier (14).

DISCUSSION

We describe here the use of a genetic expression vector that abrogates the activity of a transcription factor in a living embryo. Three main results were obtained. First, the intracellular efficacy of a scFv for this purpose was established by demonstration of the same ectopic expression of the CyIIIa⋅CAT vector as is caused by deletion of the target sites for this transcription factor. Second, we confirmed that the P3A2 factor indeed serves as a spatial repressor for the CyIIIa gene and extend this observation from CyIIIa⋅CAT expression constructs to the endogenous CyIIIa gene. Third, we discovered a hitherto unknown function of P3A2 in archenteron morphogenesis. Both this function and the effects of the P3A2 factor on CyIIIa expression are cell autonomous.

It is striking that CyIIIa⋅CAT and CyIIIa gene expression are so efficiently expanded to the oral ectoderm in embryos bearing αP3A2⋅TKO in oral ectoderm clones. P3A2 is initially a relatively prevalent maternal factor, present in about 2 × 106 molecules per embryo (16) and is later zygotically transcribed; there are a few thousand to a few hundred molecules per nucleus throughout development (16, 25). The affinity of the scFv encoded by the αP3A2⋅TKO vector for the P3A2 factor is significantly higher than that of the factor for its DNA target site (9, 13) as calculated from experiments such as that shown in Fig. 1. Thus, the scFv apparently acts as a very effective intracellular sequestering agent. Nor is any nonspecific early embryonic lethality observed, in contrast to the general deleterious effect of injecting the mAb per se into eggs (unpublished results). Furthermore, use of a genetic vehicle for producing the αP3A2 scFv ensures that it will continue to function through development (depending of course on the cis-regulatory element driving its expression), which is never reliably the case for either protein or mRNA introduced directly into the egg. The results shown in this paper confirm that αP3A2⋅TKO continues to function through embryogenesis (Fig. 3).

An unexpected aspect of the spatial derepression of the endogenous CyIIIa gene caused by introduction of αP3A2⋅TKO is that ectopic expression was observed not only in oral ectoderm but also in gut (Fig. 3 e and f). Recent studies (ref. 14, and earlier observations reviewed therein) proved that the two P3A2 sites deleted in the experiments of Kirchhamer and Davidson (14) are required to prevent ectopic oral-ectoderm expression of CyIIIa⋅CAT constructs, but no ectopic gut expression was observed in these experiments. However, there are additional potential P3A2 sites in the CyIIIa cis-regulatory element, and these may be responsible for controlling expression in gut.

A new role for P3A2 in archenteron formation was revealed when we examined the postgastrular lethal phenotype produced by αP3A2⋅TKO injection into fertilized eggs. This effect occurs only when the construct is present in large clones of archenteron cells. These cells fail to adhere to one another so that the archenteron disintegrates into a wholly or partially disorganized pile of endoderm cells. Yet these cells retain their state of specification, as monitored by expression of an endoderm-specific gene, Endo16. The implication is that genes encoding some cell surface proteins are controlled by P3A2 either directly or indirectly. If directly, it is possible that P3A2 acts positively in this context, although its function is clearly negative in regulation of the CyIIIa gene.

There are many obvious possible extensions of the TKO technology described here, both in research and potentially for gene therapy (26). We are now extending the TKO approach to several other sea urchin embryo transcription factors. This may become a general method for examination of trans-regulatory functions. One powerful potential advantage of the TKO method is the possibility of exactly controlling the time and place of TKO expression. This depends directly on the cis-regulatory system employed to drive the transcription of the TKO vector. Thus, for example, TKO vectors could be built and inserted into the mouse genome that would blockade given transcription factors only in given cell types at given stages of development. This could provide a decisive advantage given that transcription factors are often utilized at many stages of the life cycle and used for many diverse developmental purposes.

Acknowledgments

We express great appreciation to Drs. James Coffman and Carl Parker for critical reviews of the manuscript. We thank Drs. R. Andrew Cameron and Carmen Kirchhamer for their invaluable insight and discussions, and Armenia Gregorian, Vanessa Moy, and Gayle Zborowski for their excellent technical assistance. We are grateful to Drs. Robert Maxson of University of Southern California and Lynne Angerer of the University of Rochester for providing promoter clones. Research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HD-05753 and by the Stowers Institute for Medical Research. L.D.B. was supported by a California Institute of Technology Gosney Fellowship and by National Institutes of Health Grant HD-07257.

ABBREVIATIONS

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility-shift assay

- WMISH

whole-mount in situ hybridization

- scFv

single-chain antibody

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- H2b

histone 2b

References

- 1.Arnone M I, Davidson E H. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1997;124:1851–1864. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.10.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davidson E H, Cameron R A, Ransick A. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:3269–3290. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.17.3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuh C-H, Bolouri H, Davidson E H. Science. 1998;279:1896–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5358.1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirchhamer C V, Yuh C-H, Davidson E H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9322–9328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnone M I, Bogarad L D, Callazo A, Kirchhamer C V, Cameron R A, Rast J P, Gregorians A, Davidson E H. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1997;124:4649–4659. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron R A, Coffman J A. In: Cell Fate and Lineage Determination. Moody S A, editor. San Diego: Academic; 1998. , in press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Char B R, Tan H, Maxson R. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1994;120:1929–1935. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.7.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schier A F, Gehring W J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1450–1454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calzone F J, Höög C, Teplow D B, Cutting A E, Zeller R W, Britten R J, Davidson E H. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1991;112:335–350. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.1.335. , 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeSimone S M, White K. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3641–3649. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomez-Cuadrado A, Martin M, Noel M, Ruiz-Carillo A. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6670–6685. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Virbasius C M A, Virbasius J V, Scarpulla R C. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2431–2445. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12a.2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Höög C, Calzone F J, Cutting A E, Britten R J, Davidson E H. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1991;112:351–364. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.1.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirchhamer C V, Davidson E H. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;122:333–348. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hough-Evans B R, Franks R R, Zeller R W, Britten R J, Davidson E H. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1990;110:41–50. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeller R W, Britten R J, Davidson E H. Dev Biol. 1995;170:75–82. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gan L, Wessel G M, Klein W H. Dev Biol. 1990;142:346–359. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90355-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao A, Colin A M, Bell J, Baker M, Char B R, Maxson R. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6730–6741. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei Z, Angerer L M, Gagnon M L, Angerer R C. Dev Biol. 1995;171:195–211. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livant D L, Hough-Evans B R, Moore J G, Britten R J, Davidson E H. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1991;113:385–398. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franks R R, Anderson R, Moore J G, Hough-Evans B R, Britten R J, Davidson E H. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1990;110:31–40. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livant D, Cutting A, Britten R J, Davidson E H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7607–7611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nocente-McGrath C, Brenner C A, Ernst S G. Dev Biol. 1989;136:264–272. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ransick A, Ernst S, Britten R J, Davidson E H. Mech Dev. 1993;42:117–124. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90001-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cutting A E, Höög C, Calzone F J, Britten R J, Davidson E H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7953–7957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rondon I J, Marasco W A. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:257–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]