Abstract

To obtain mutants for the study of the basic biology and pathogenic mechanisms of mycoplasmas, the insertion site of transposon Tn4001T was determined for 1,700 members of a library of Mycoplasma pulmonis mutants. After evaluating several criteria for gene disruption, we concluded that 321 of the 782 protein coding regions were inactivated. The dispensable and essential genes of M. pulmonis were compared to those reported for Mycoplasma genitalium and Bacillus subtilis. Perhaps the most surprising result of the current study was that unlike other bacteria, ribosomal proteins S18 and L28 were dispensable. Carbohydrate transport and the susceptibility of selected mutants to UV irradiation were examined to assess whether active transposition of Tn4001T within the genome would confound phenotypic analysis. In contrast to earlier reports suggesting that mycoplasmas were limited in their DNA repair machinery, mutations in recA, uvrA, uvrB and uvrC resulted in a DNA-repair deficient phenotype. A mutant with a defect in transport of N-acetylglucosamine was identified.

Introduction

Considerable effort has been devoted to determining the number of genes required to support life; i.e., the essential housekeeping genes of a “minimal cell”. The use of comparative genomics has allowed the approximation of a minimal complement of essential genes for a free living bacterium (Gil et al., 2004). Allelic replacement, antisense RNA, and random transposon mutagenesis have been employed to experimentally estimate the number of essential genes in several species of bacteria (Gallagher et al., 2007; Glass et al., 2006; Jacobs et al., 2003; Ji et al., 2001; Kobayashi et al., 2003; Liberati et al., 2006; Salama et al., 2004; Song et al., 2005; Suzuki et al., 2006). Databases of essential bacterial genes are available at http://tubic.tju.edu.cn/deg/and http://www.nmpdr.org/content/essential.php (McNeil et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2004).

Mycoplasmas are ideal organisms for the study of minimal genomes, having undergone a high rate of evolution involving multiple reductions in genome size (Maniloff, 1992). Mycoplasma genitalium, a pathogen of the human urogenital and respiratory tracts, possesses the smallest genome, 580 kb, of any known organism that can be grown in pure culture and is assumed to closely represent a naturally occurring example of a minimal cell (Fraser et al., 1995). A 1999 study used transposon Tn4001 as an insertional mutagen of M. genitalium and M. pneumoniae, and follow-up work described an essential minimal genome set of 387 protein coding and 43 structural RNA genes for M. genitalium (Glass et al., 2006; Hutchinson et al., 1999). If these results are compared to those obtained with Bacillus subtilis, where 271 genes were identified as essential (Kobayashi et al., 2003), it appears that the much larger genome of B. subtilis (4200 kb) affords a degree of functional overlap whereby fewer genes confer essential cellular functions. Correspondingly, genomic streamlining resulting in numerically fewer coding sequences as found in mycoplasmas necessitates a larger set of essential genes (Chalker et al., 2001; Lamichhane et al., 2003).

M. pulmonis strain CT is a murine pathogen originally isolated from a mouse lung and is the agent of murine respiratory mycoplasmosis (Davis et al., 1986). Infection of rats and mice with M. pulmonis offers an outstanding model of chronic inflammatory respiratory disease. The 963-kb genome of M. pulmonis contains 782 annotated open reading frames (ORFs) (Chambaud et al., 2001). Attempts to specifically target genes by generalized (homologous) recombination in M. pulmonis have not been successful, but transposons are effective for random insertional mutagenesis (Dybvig et al., 2000).

We have constructed a transposon library of M. pulmonis strain CT and determined the nucleotide position of transposon integration for about 1,700 clones. A total of 1,856 distinct transposon insertion sites were identified, with two or more transposon insertion sites occurring in some library members. Mutations in genes producing two observable ex vivo phenotypes, DNA repair and carbohydrate transport, were chosen for additional analysis. This mutagenesis library will be invaluable for examining the effect of selected gene knockouts on the virulence of M. pulmonis in a rodent model. Here, we compare the mutable genes of M. pulmonis with those of M. genitalium. Although mycoplasmas lack cell walls, they are phylogenetically related to Gram-positive bacteria with genomes of low G+C content. Therefore, the mutable genes of M. pulmonis are also compared in this study to those of B. subtilis.

Results

Transposon insertion sites

The nucleotide position of the transposon in library members was determined by sequencing an inverse PCR product containing the junction between the transposon and the mycoplasma genome. The sequence was compared to the complete genome sequence of M. pulmonis to identify the genomic location of the transposon (Chambaud et al., 2001). A total of 1,856 different genomic sites for transposon insertion were mapped.

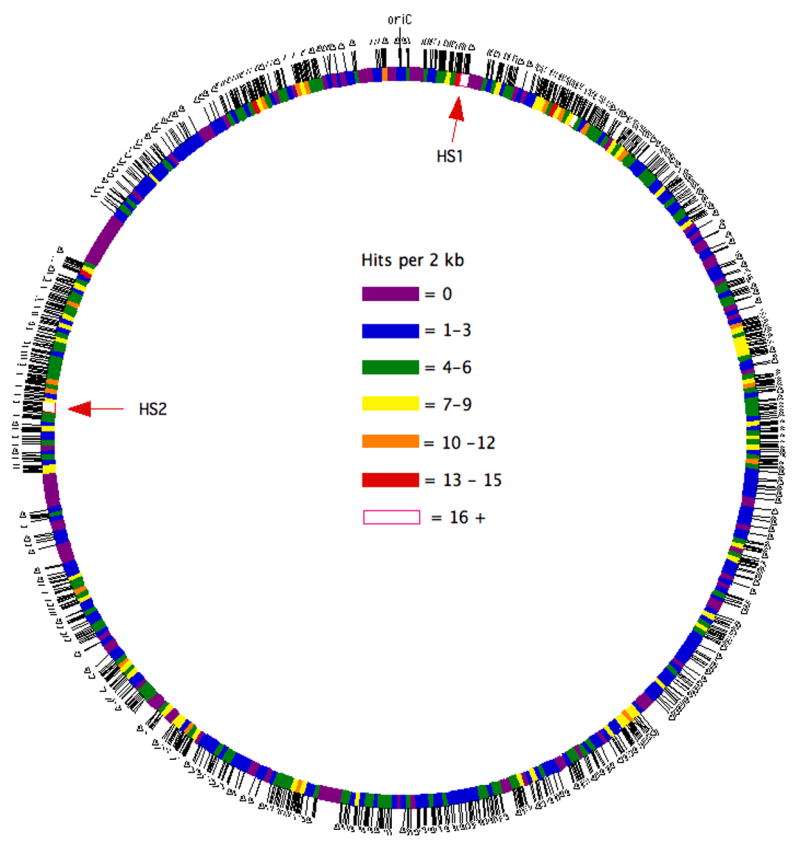

Tn4001 inserts into chromosomal DNA at nearly random sites. With rare exceptions, no two transformants contained a transposon insertion at the same genomic location. A map illustrating the density of transposon insertion sites within the genome is shown in Fig. 1. Regions of the genome with few insertion sites generally contained genes or operons that are predicted to be essential based on annotated function. Some regions of the genome seem to have an overabundance of transposon insertion sites. Whether there is something unusual about the architecture of these regions that favors transposon integration remains to be determined. Surprisingly, one of the hotspots for transposon insertion, HS1, encompasses what appears to be an essential NADH oxidase gene, MYPU_0230. The other hotspot, HS2, is within an operon predicted to code for a sugar ABC transport system.

Fig. 1.

Map illustrating the density of transposon insertion sites in the M. pulmonis genome. Each tick mark represents a transposon insertion. The genome was divided into 480 blocks of 2-kb each, with the number of transposon insertion sites in each block color coded as indicated. oriC refers to the chromosomal origin of replication. HS1 and HS2 refer to hot spots for transposon insertion.

Criteria for gene inactivation

Several factors were evaluated for their suitability in predicting whether a gene was likely to be inactivated by a transposon insertion. Tn4001 is bound by copies of the insertion element IS256 which contains an outward promoter that functions in mycoplasmas (Romero-Arroyo et al., 1999) and could contribute to polar effects on the expression of adjacent genes. Consequently, no gene was considered inactivated on the basis of whether the transposon would dissociate the gene’s coding region from its native promoter. Genome annotations often list the first potential start codon of an open reading frame as the 5′ end of the coding region, but the true translation start may often lie further downstream. As an example, we initially identified three transformants containing insertions near the 5′ end of MYPU_7780 coding for methionine sulfide reductase (MsrA), a potential virulence factor and possibly an essential gene. Alignment of the predicted MsrA protein with the amino acid sequence of MsrA proteins of other bacteria indicates that the correct translation start is an ATG site located 33 nucleotides downstream of the annotated TTG start. Using the corrected translation start, our library contained no transformants with disruptions in MYPU_7780. Another issue is the possibility that some genes may recruit pseudoalternative sites for translation initiation when the primary translation start has been disrupted by the transposon. A previous study in M. genitalium considered a gene to be inactivated if the transposon truncated the first three codons from the remainder of the coding region (Glass et al., 2006). Because of the inherent uncertainty as to the true translation start site(s) of many genes, we chose as a default criterion that at least 10% of the coding region must be truncated from the annotated 5′ start site for a gene to be considered inactivated. Exceptions were made when the transposon would disrupt a known or predicted signal peptide sequence or transmembrane domain. The M. pulmonis genome codes for over 50 lipoproteins. Genes coding for lipoproteins were considered inactivated even if less than 10% of the 5′ end of the gene was dissociated from the rest of the coding region because the signal peptide sequence would be truncated from the remainder of the protein.

When the transposon inserted near the 3′ end of an ORF, we had initially considered a gene to be inactivated if the gene product were truncated by at least 10%. However, a few genes that should be essential, such as the one coding for ribosomal protein L19, would have been inactivated according to this criterion. By changing the criterion to truncation at the 3′ end by at least 15%, examples of inactivation of obviously essential genes were eliminated. Using the 15% criterion at the 3′ end, 321 genes were inactivated in the library. When the criterion was changed to truncation by at least 20%, the number of genes inactivated was reduced to 312. None of the 9 genes that would be inactivated by the 15% but not the 20% criterion would be predicted to be essential based on annotated function (Table 1), and therefore 15% truncation was chosen as the final criterion. In summary, it was optimal to consider a gene to be inactivated if transposon insertion resulted in the truncation of at least 10% from the 5′ end or 15% from the 3′ end of an ORF. A complete list of the genes inactivated is provided in Table S1.

Table 1.

M. pulmonis ORFs that are inactivated using a criterion of 15% but not 20% truncation at the 5′ end

| Gene | Product | Gene length (bp) | Ortholog in M. genitalium |

|---|---|---|---|

| MYPU_0630 | Hypothetical protein | 552 | no |

| MYPU_1480 | Hypothetical protein | 984 | no |

| MYPU_1750 | Hypothetical protein | 216 | no |

| MYPU_2450 | Lipoprotein | 2757 | no |

| MYPU_3250 | Conserved protein | 1896 | no |

| MYPU_3490 | Hypothetical protein | 1386 | no |

| MYPU_3840 | Hypothetical membrane protein | 2562 | no |

| MYPU_5920 | Hypothetical protein | 198 | no |

| MYPU_6050 | Lipoprotein | 504 | no |

Uncomfirmable mutants

There were 16 examples of genes (Table 2) that are absent from Table S1 but were disrupted by the transposon according to the initial inverse PCR sequence. In these cases, analysis of the transposon’s genomic location by direct PCR failed to confirm the inverse PCR sequencing data, or an intact copy of the gene was detected by direct PCR in each of the subclones of the transformant. Similar findings of genes that were disrupted in the primary transformant but not in subclones thereof have been reported for transposon mutagenesis of M. genitalium (Glass et al., 2006). Most of these unconfirmable insertions were represented by only one library member. A striking exception is the 1.4-kb gene MYPU_0230 that was disrupted at different nucleotide positions in 27 primary transformants. MYPU_0230 codes for NADH oxidase and is essential in M. genitalium. The MYPU_0230 gene and its immediately upstream sequences correspond to the HS1 hotspot region (Fig. 1) of the M. pulmonis genome. We assume that MYPU_0230 is essential, but it is unclear how the primary transformants with disruptions in an essential gene would have been sufficiently viable to form a colony.

Table 2.

Genes disrupted in primary transformant(s) but not confirmable

| ORF | Product | Gene length (bp) | No. transformants |

|---|---|---|---|

| MYPU_110 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 1374 | 1 |

| MYPU_230 | NADH oxidase | 1434 | 27 |

| MYPU_1330 | Hypothetical protein | 1737 | 1 |

| MYPU_1650 | GTPase translation factor, putative | 1107 | 4 |

| MYPU_2370 | Phosphate acetyltransferase | 954 | 1 |

| MYPU_2440 | COF family HAD hydrolase protein, conserved | 810 | 1 |

| MYPU_2770 | Phosphopentomutase | 1185 | 1 |

| MYPU_2820 | Lipoprotein | 2628 | 1 |

| MYPU_3110 | Formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase, MutM | 363 | 1 |

| MYPU_3230 | Lipoprotein | 1893 | 1 |

| MYPU_3740 | Lipoprotein | 1446 | 4 |

| MYPU_4100 | Oligopeptide ABC transporter permease protein OppB | 1104 | 1 |

| MYPU_4440 | Hypothetical protein | 1524 | 1 |

| MYPU_6160 | Hypothetical protein | 504 | 1 |

| MYPU_6290 | Hypothetical protein | 141 | 1 |

| MYPU_7570 | Hypothetical protein | 294 | 2 |

Robustness of library

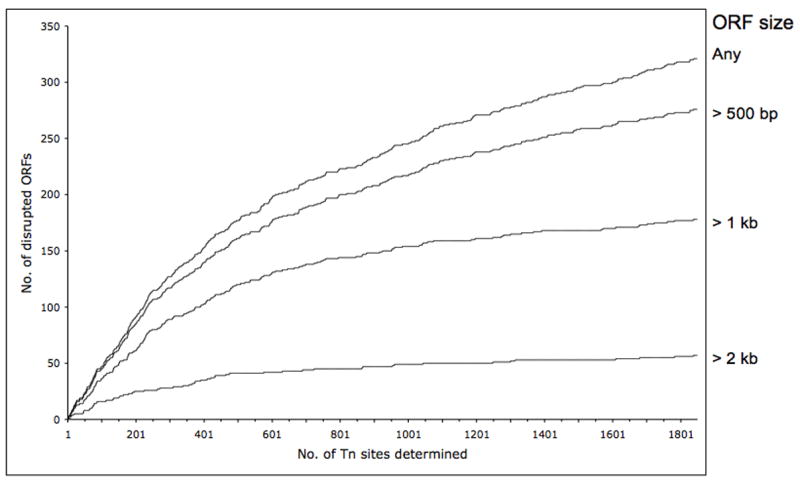

About half of the 782 ORFs in the 960-kb genome of M. pulmonis should be essential for growth, where essentiality is defined as the ability to form a colony and propagate in broth using our growth conditions. This would yield an effective target size available for transposon integration of around 500 kb. The mapping of 1,800 insertion sites over a 500-kb target genome yields a density of about 1 transposon integration per 300 bp of nonessential DNA. A graphical representation of the number of genes disrupted versus the number of transposon insertion sites mapped is shown in Fig. 2. Although this level of coverage is inadequate to disrupt all nonessential genes, the number of inactivating insertions in genes larger than 1 kb has nearly reached a plateau. For small genes, especially those under 500 bp, the number of genes disrupted is still on the rise. We consider individual genes larger than 1 kb but not disrupted in any library member to be essential for viability. Also, we assume that at least one of the overlapping genes of a large operon to be essential if the operon lacks transposon disruptions, even if each of the individual genes of the operon are smaller than 1 kb.

Fig. 2.

Number of mutated ORFs of size greater than 2 kb, greater than 1 kb, greater than 500 bp or of any size plotted as a function of the number of transposition insertion sites mapped.

Essential genes

Genes that appear to be essential in M. pulmonis based on lack of hits (no insertions, but size > 1 kb) or essentiality in M. genitalium and B. subtilis are provided in Table S2. Not listed are tRNA or rRNA genes, none of which were disrupted in the library. Each of the genes listed in Table S2 may not be essential for growth per se. Disruption of some of these genes may permit a low level of growth that proves insufficient for the isolation of subclones lacking a detectable copy of the wild-type gene. The 310 genes listed in the table are likely an underestimate of the number of essential genes since some are omitted because they are smaller than 1 kb. Considering that the genome size of M. pulmonis is intermediate between M. genitalium and B. subtilis, it follows that it should possess fewer essential genes than the 382 reported for M. genitalium but more than the 271 reported for B. subtilis (Glass et al., 2006; Kobayashi et al., 2003). In most cases for which an ortholog exists of an essential M. pulmonis gene, the ortholog is also essential in M. genitalium. Examples of genes that are essential in both mycoplasmas but nonessential in B. subtilis include those coding for a spermidine/putrescine transport system (MYPU_4220–4250), a glycosyltransferase (MYPU_7700), the Hpr kinase (MYPU_7110), an oligopeptide transport system (MYPU_2830–2850), pyruvate and acetate kinases (MYPU_2400 and MYPU_2380), and NADH oxidase. Interestingly, one of the essential genes in M. pulmonis is of unknown function and over 8 kb (MYPU_3130). As several lipoproteins are essential, we consider the lipoprotein signal peptidase (lspA, MYPU_6680) to be essential, even though it appears dispensable in M. genitalium and B. subtilis.

Fifty-three genes are essential in M. pulmonis but absent or dispensable in M. genitalium. Of these, 12 are essential in B. subtilis (Table 3). Eight of these genes have orthologs in M. genitalium and their dispensability in that species warrants confirmation. One example is MYPU_7680, coding for an ATP-dependent helicase. This large 2.2-kb gene is essential in M. pulmonis despite the presence of an apparent paralog in the dispensable gene MYPU_6980. The M. genitalium ortholog MG244 is dispensable. Taken together, our results support the prediction that the number of essential genes in M. pulmonis is intermediate between those reported for the smaller genome of M. genitalium and the larger genome of B. subtilis.

Table 3.

Essential genes in M. pulmonis and B. subtilis but absent or dispensable in M. genitalium

| Gene | Product | Gene symbol | Gene length | Mg ortholog | Essential in Mg, Bs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYPU_1150 | Segregation and condensation protein A | scpA | 747 | MG213 | No, Yes |

| MYPU_1160 | Segregation and condensation protein B | scpB | 624 | MG214 | No, Yes |

| MYPU_1680 | Phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase | pgsA | 615 | MG114 | No, Yes |

| MYPU_3030 | SpoU class tRNA/rRNA methyltransferase | 525 | MG346 | No, Yes | |

| MYPU_3740 | Lipoprotein | 1449 | NA | NA, Yes | |

| MYPU_4060 | Conserved hypothetical protein | ymdA | 1338 | NA | NA, Yes |

| MYPU_4740 | Phosphatidate cytidylyltransferase | cdsA | 969 | MG437 | No, Yes |

| MYPU_4830 | Nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase | 1005 | NA | NA, Yes | |

| MYPU_5110 | Transketolase | tktA | 1848 | MG066 | No, Yes |

| MYPU_7140 | Chromosome segregation ATPase Smc | smc | 2940 | MG298 | No, Yes |

| MYPU_7220 | Chromosome replication protein | dnaB | 945 | NA | NA, Yes |

| MYPU_7680 | ATP-dependent helicase PcrA | pcrA, uvrD | 2184 | MG244 | No, Yes |

Essential genes in M. genitalium (Mg) and B. subtilis (Bs) are as reported by Glass et al. and Kobayashi et al. (Glass et al., 2006; Kobayashi et al., 2003).

Dispensable genes

Of the 321 genes disrupted in M. pulmonis (Table S1), 51 have essential homologs in M. genitalium, 13 have essential homologs in B. subtilis, and 9 have essential homologs in both species (Table 4). A clear distinction between the mycoplasmas is that several genes encoding DNA repair functions, (MYPU_7100 uvrA), MYPU_0960 (uvrB) and MYPU_1560 (uvrC), are dispensable in M. pulmonis but essential in M. genitalium. There are no paralogs to these genes elsewhere in the M. pulmonis genome. Paralogs do exist in the genome of M. pulmonis for the genes encoding cysteine desulferase, fructose-biphosphate aldolase, lysyl-tRNA synthetase, ribosomal protein L33, and the PcrA helicase, offering a simple explanation for their apparent dispensability. The dispensability of genes coding for ribonucleoside reductase is not so surprising considering that some species of mycoplasma (M. agalactiae, M. mobile and ureaplasma) lack these genes altogether. The dispensability of genes coding for ribosomal proteins S18 and L28 may be the most surprising result obtained in this study. Moreover, the M. pulmonis mutants with disruptions in these genes had no obvious growth defect. These proteins are essential in most organisms including E. coli. At least 6 other ribosomal proteins are nonessential in E. coli, but mutants lacking any of these proteins grow very poorly (Bubunenko et al., 2007).

Table 4.

Genes dispensable in M. pulmonis but essential in B. subtilis a

| Gene | Product | Gene symbol | Gene length (bp) | Mg ortholog | Essential in Mg, Bs | Mp paralog |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYPU_1630 | Ribonuclease III (RNase III) | rnc | 726 | MG367 | no, yes | no |

| MYPU_1720 | Cysteine desulferase | csd | 1182 | MG336 | yes, yes | MYPU_1730 |

| MYPU_3600 | Fructose-biphosphate aldolase | fba | 843 | MG023 | yes, yes | MYPU_1100 |

| MYPU_3900 | Lysyl-tRNA synthetase | lysS | 1533 | MG136 | yes, yes | MYPU_4020 |

| MYPU_4020 | Lysyl-tRNA synthetase | lysS | 1476 | MG136 | yes, yes | MYPU_3900 |

| MYPU_4890 | Ribosomal protein L33 | rpmG | 153 | MG325 | yes, yes | MYPU_1800 |

| MYPU_5390 | Ribonucleotide-diphosphate reductase beta subunit | nrdF | 1026 | MG229 | yes, yes | no |

| MYPU_5410 | Ribonucleotide-diphosphate reductase alpha subunit | nrdE | 2136 | MG231 | yes, yes | no |

| MYPU_6090 | Ribosomal protein S18 | rpsR | 318 | MG092 | yes, yes | no |

| MYPU_6840 | GTPase | 819 | MG110 | no, yes | no | |

| MYPU_6960 | Ribosomal protein L28 | rpmB | 192 | MG426 | yes, yes | no |

| MYPU_6980 | ATP-dependent helicase PcrA | pcrA, uvrD | 2205 | MG244 | no, yes | MYPU_7680 |

| MYPU_7210 | Dephospho-coenzyme A kinase | coaE | 519 | MG264 | no, yes | no |

Essential genes in M. genitalium (Mg) and B. subtilis (Bs) are as reported by Glass et al. and Kobayashi et al. (Glass et al., 2006; Kobayashi et al., 2003). M. pulmonis, Mp.

Phenotypic analysis of selected mutants

Tn4001T transposes actively in the M. pulmonis genome. Excision of the transposon is usually precise, restoring gene function (Mahairas et al., 1989). Experiments were undertaken to determine whether mutants selected from the transposon library displayed a phenotype that was sufficiently stable to assess the loss of function. To this end, mutants with defects in DNA repair-related genes were examined for susceptibility to irradiation by UV light. Other mutants were screened for loss of transport of selected carbohydrates.

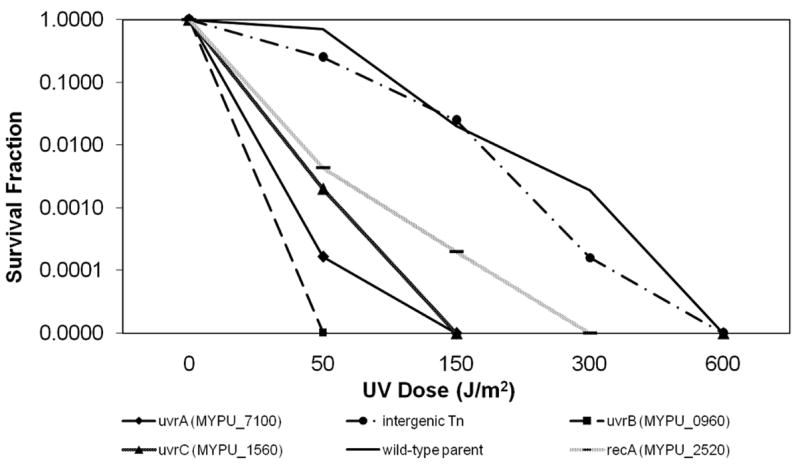

Mutants with transposon disruptions in MYPU_2520 (recA), MYPU_1590 (recF), MYPU_6570 (ruvA), MYPU_6580 (ruvB), MYPU_7100 (uvrA), MYPU_0960 (uvrB) and MYPU_1560 (uvrC) were assayed for their ability to recover from DNA damage produced by exposure to UV irradiation. Compared to both wild-type M. pulmonis and a control containing the transposon located within a gene unrelated to DNA repair, UV irradiation was considerably more lethal to uvrA, uvrB, uvrC and recA mutants than to controls (Fig. 3). Disruptions in ruvA, ruvB, and recF resulted in a survival response comparable to wild-type M. pulmonis (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Repair of UV-damaged DNA. The surviving fraction of CFU was plotted as a function of applied UV exposure. Non-irradiated samples of each mutant were assessed as a control. The data shown are from a single experiment and are representative of 4 individual experiments.

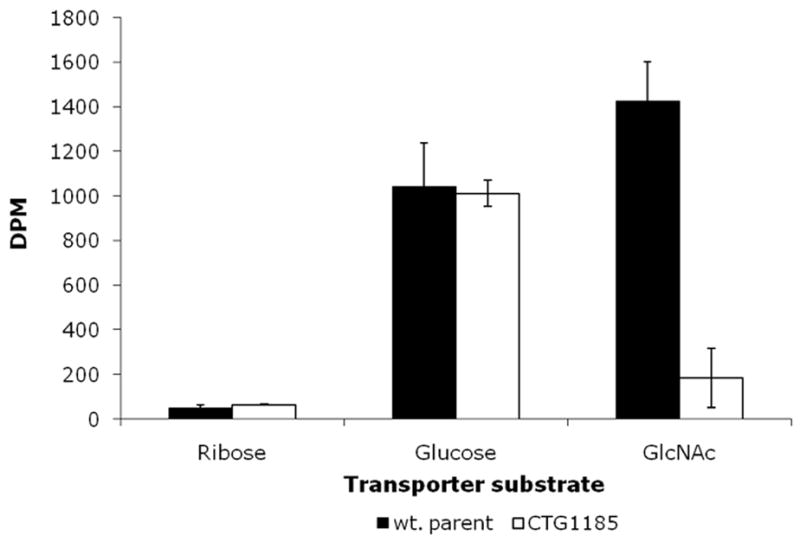

In assays for carbohydrate uptake, glucose, mannose, maltose, N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), and glycerol were shown to be transported in wild-type M. pulmonis. No transport of ribose, lactose, galactose, or mannitol was detected. Mutants with disruptions in the annotated transporter genes MYPU_0980, 3450, 4970, 6400 and 7500 were examined for transport of each test compound. Because each of these ORFs lies within a different operon, we anticipated that each would be involved in the transport of a different substrate. We were thus surprised that no defect in carbohydrate transport was observed for all mutants but one. The exception was library member CTG1185 containing a transposon disruption in MYPU_6400, a gene annotated as a maltodextrin ABC transporter permease. CTG1185 demonstrated a marked deficiency in the transport of GlcNAc (Fig. 4). Therefore, transposon mutations in M. pulmonis are sufficiently stable to evaluate phenotype despite occasional transposition of Tn4001T.

Fig. 4.

Transport of GlcNAc. Incorporation of radiolabeled GlcNAc at 18 hours. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to create a transposon knockout library to serve as a resource for studying the relationships between the basic biology and pathogenesis of mycoplasmas. The identification of mutants defective in DNA repair and transport of GlcNAc suggests that leakiness of phenotype due to transposition of Tn4001T to secondary sites is not an insurmountable issue and that the library will be valuable as anticipated. We are especially interested in mutations affecting potential virulence factors, surface antigens, membrane transporters, the synthesis of polysaccharides, and biofilm formation (Simmons et al., 2007). The M. pulmonis genome codes for few recognizable virulence factors. Adherence to host tissue and immune evasion are likely to be primary contributors to the pathogenesis and tenacity of mycoplasmal infection. The Vsa lipoproteins are of particular interest because they influence adherence properties, the susceptibility of the mycoplasma to killing by complement, and the avoidance of adaptive immune responses through gene rearrangements associated with phase variation (Gumulak-Smith et al., 2001; Simmons and Dybvig, 2003; Simmons et al., 2004). The particular vsa gene residing at the expression locus in the mycoplasma genome was not disrupted in any library member, suggesting an essential cellular function for Vsa. The gene (MYPU_5310) producing the DNA site-specific recombinase responsible for catalyzing the gene rearrangements at the vsa locus was disrupted, resulting in phase-locked mutants (Sitaraman et al., 2002).

Few studies using global transposon mutagenesis have taken the effort to confirm the disruption of each mutable ORF, and fewer – if any – have analyzed the data using a variety of criteria for gene inactivation. We do not consider a gene inactivated whenever the transposon is within the first 10% of the gene’s coding region. Previous investigations considered a gene inactivated if at least 3 amino acids would be missing from the amino terminus (Glass et al., 2006). Using our criteria, an analysis of transposon mutants in M. genitalium may yield fewer dispensable genes than reported. If we change the 5′ end criteria to truncation of only 5% instead of 10%, additional M. pulmonis genes would have been considered inactivated in our library. One of these genes was MYPU_3100, coding for formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase, an essential enzyme in M. genitalium. Another gene that would be inactivated by the less stringent 5′ end criterion would be MYPU_1880, coding for the damage-inducible DNA polymerase IV enzyme. Whether MYPU_3100 and 1880 encode essential functions in M. pulmonis requires further investigation.

The gene disrupted most often in primary transformants of the transposon library was the essential NADH oxidase gene, MYPU_0230. How can we explain the frequent disruption of an essential gene? Cultures of M. pulmonis contain clusters of hundreds if not thousands of cells (Simmons et al., 2007). If multiple cells within a cluster were transformed simultaneously with transposons integrating in different genes, the resulting transformant colony would be a mixed population. A cell in a mixed population containing a transposon insertion in an essential gene may grow very poorly, but be initially present in sufficient numbers to allow identification. Such a transformant would be subsequently lost during subculturing and passage. Next, some cells within the population may have the transposon inserted within a gene that is essential for growth provided that other cells could supply the essential factor in trans. NADH oxidase may be one such factor. Transposition events might also generate cell subpopulations that could supply factors in trans. A transformed cell might initially have the transposon at an innocuous site, but the transposon may transpose into an essential gene such as MYPU_0230 during early development of a colony. Such transposition events may not necessarily be intragenomic as transfer of the transposon between cells has been shown to occur (Teachman et al., 2002).

We do not believe all of the paralogous genes in M. pulmonis are functionally redundant. The two lysyl-tRNA synthetase genes (Table 4) are probably true homologs, the apparent product of a gene duplication event involving the acquisition of a mobile element (Dybvig et al., 2007). The two ribosomal protein L33 genes are probably functionally redundant as well. But only one of the two ATP-dependent helicases encoded by MYPU_6980 and 7680 was dispensable, suggesting these enzymes may have different activities. The two lipoate-protein ligase enzymes encoded by MYPU_0320 and 4430 differ significantly in amino acid sequence, being more closely related to enzymes from other bacteria than to each other. Therefore, these two enzymes are dispensable but may differ in substrate specificity.

Fourteen of the disrupted M. pulmonis genes with orthologs identified as essential in M. genitalium specify transport proteins, some of which may perform redundant functions in M. pulmonis. In total, 69 ABC transporter genes are found in M. pulmonis, many of which are indicated to be specific for carbohydrates. This is in contrast to the total of 29 ABC transport genes identified in M. genitalium. Genomic comparisons of M. pulmonis with M. genitalium suggest that additional transporter genes are responsible for much of the difference in genome size between the two species (Rocha and Blanchard, 2002). There may be functional overlap in the substrates recognized by some of the transporters because the mutants that were predicted to have a role in carbohydrate transport had no obvious defect in transport for any of the compounds that were tested. The exception was the knockout mutant of MYPU_6400 that had a defect in transport of GlcNAc. Presumably, the flanking MYPU_6390 and 6410 genes code for the other subunits of the GlcNAc ABC transporter, but mutants with disruptions in these ORFs were not examined.

Some studies suggest that mycoplasmas lack appreciable DNA repair (Dybvig and Voelker, 1996). recA (MYPU_2520) has previously been shown to be involved in repair of UV-induced DNA damage in the phylogenetically related organism Acholeplasma laidlawii (Dybvig and Woodard, 1992). In the current study, library members with transposon disruptions in uvrA, uvrB, uvrC and recA had a defect in DNA repair. Therefore, the mycoplasmas have more DNA repair capability than early studies might suggest. The uvrA, B and C genes are essential in M. genitalium, underscoring their functional importance.

Considering the essential roles of ribosomal proteins S18 and L28 in other bacteria, the robust growth of mutants with disruptions in these genes is surprising. Although these proteins were essential in M. genitalium, we have also knocked out the S18 gene in Mycoplasma arthritidis (D.S. Jordan and K. Dybvig, unpublished). It has been suggested that mycoplasmas can withstand a higher mutation rate than other bacteria because of their small genome size (Woese, 1987). Mycoplasma rRNA molecules have several examples of base substitutions at sites that are conserved in other bacteria (Weisburg et al., 1989). Perhaps the structure of the mycoplasma ribosome has evolved in such a way that some of the ribosomal proteins are now of marginal importance.

Experimental procedures

Library construction

The murine pathogen M. pulmonis strain CT was cultured in mycoplasma broth (MB) and assayed for colonies on mycoplasma agar (MA) (Dybvig et al., 2000; Simmons and Dybvig, 2003). The mycoplasma was transformed with the transposon Tn4001T -containing plasmid pIVT-1 using the polyethylene glycol-mediated method as described previously (Dybvig et al., 1995; Dybvig et al., 2000). pIVT-1 does not replicate in mycoplasmas, and transformants are only obtained when Tn4001T transposes into the mycoplasma genome. Transformants were selected on agar supplemented with 3 μg of tetracycline/ml. Individual transformant colonies were picked and grown at 37°C in 1 ml broth containing tetracycline. Each culture was frozen at −80°C in broth supplemented with 15% glycerol. A total of 2,000 transformants were preserved.

Mapping of transposon insertion sites

The genomic location of the transposon was determined for each transformant by DNA sequence analysis of the junction between the transposon and the adjacent genomic DNA. The junction was amplified by inverse PCR. The sequence of the PCR product was compared to the complete genome sequence for identification of the transposon insertion site (Chambaud et al., 2001). For about one-half of the library members, the inverse PCR conditions and primers used to map the transposon location were as described previously (Teachman et al., 2002). For the other transformants the protocol was similar except that genomic DNA was digested with AluI instead of NlaIII and the primers for inverse PCR were ACTGAGCCTTTCGCTACTGGCTAATAATTCACT and CAAAGTTTCTCAAAAGAGTATTCAGGTGGCG. For some transformants, more than one inverse PCR product was obtained. The products were gel purified and sequenced individually to map the location of each copy of the transposon.

Confirmation of gene dispensability

To confirm that an ORF was dispensable, at least one transformant with the gene disrupted was analyzed by direct PCR to verify that the transposon integration site was correct and to determine whether an intact copy of the gene might be present in the template preparation. To confirm the genomic location of transposon, the previously described o.6 primer (Teachman et al., 2002) that anneals near the end of the transposon was paired with a gene-specific primer that annealed to sequences in the adjacent genomic DNA. A negative control consisted of amplification of wild-type mycoplasma DNA preparation that lacked the transposon. The possible presence of an intact copy of the gene was assessed by using a PCR primer pair that flanked the site of transposon integration. The lack of a PCR product would indicate that no intact gene was present in the transformant. Template DNA from the wild-type parent strain was used as a positive control. PCR products were analyzed on agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. If the PCR data confirmed the location of the transposon and indicated that no intact copy of the gene was present in the transformant, it was concluded that the gene was indeed mutable. If the transposon location was confirmed but a PCR product corresponding to an intact copy of the gene was also obtained, the transformant was subcloned. Individual filter clones were analyzed by direct PCR as described above to determine whether the transposon still resided in the gene and whether an intact copy of the gene was present in the template. Again, if in any subclone the transposon disrupted the gene and no intact copy of the gene was identified by PCR, it was concluded that the gene was mutable.

M. pulmonis gene annotation and homolog identification

Annotations of M. pulmonis genes are available at http://genolist.pasteur.fr/MypuList/. However, for the purpose of this study the gene products were reannotated by using a combination of BLAST and COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups) analyses at NCBI. The identification of orthologs in the genomes of B. subtilis and M. genitalium was facilitated by additional BLAST analysis at http://genolist.pasteur.fr/SubtiList/ and http://cbi.labri.fr/outils/molligen/. Proteins with predicted signal peptides or transmembrane regions were identified by using InterProScan at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/webservices/services/interproscan.

Assessment of DNA repair

M. pulmonis library members containing transposon disruptions in genes coding for potential DNA repair proteins were grown in MB supplemented with sodium bicarbonate (0.3%) and tetracycline (3.0 μg/ml) in a 7.5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 11,000 × g, suspended in 500 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and placed into the wells of a flat-bottom 12- or 24-well plate. Mycoplasma cells were exposed to 254 nm UV radiation using a DNA Stratalinker (Stratagene). 10 μl samples were removed into MB after 50, 150, 300 and 600 J/m2 exposures to UV. Serial dilutions of cells were assayed for CFU on MA containing 0.3% sodium bicarbonate and tetracycline.

Assessment of carbohydrate transport

Transposon mutants containing disruptions in genes predicted to be involved in the transport of sugars were analyzed for their ability to transport a variety of carbohydrates. Transport assays were performed with 3H- or 14C-labeled sugar substrates (Sigma-Aldrich). The compounds tested for transport were radiolabeled D-glucose-1-14C, D-galactose-1-14C, lactose-(glucose-1-14C), N-acetyl-D-glucosamine-1-14C, glycerol-1, 2, 3-3H, maltose-UL-14C, mannose-UL-14C, D-mannitol-1-14C, and D-ribose-1-3H. Cells were grown to logarithmic phase, harvested by centrifugation, and suspended in modified MB that lacked supplemental glucose other than what is present in horse serum. Labeled substrates (1 uCi) were added and incubated with the cells for 18–48 hours. The cells were centrifuged, washed twice in cold PBS, and gently filtered through 0.2 um membranes. The membranes were washed with 10 ml of cold PBS and assayed for radioactivity by liquid scintillation counting. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Liu, X. Shen, and N. Zou for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grant AI63909. During preparation of this manuscript, C.T. French was supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award GM007185.

References

- Bubunenko M, Baker T, Court DL. Essentiality and transcription antitermination proteins analyzed by systematic gene replacement in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:2844–2853. doi: 10.1128/JB.01713-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalker AF, Minehart HW, Hughes NJ, Koretke KK, Lonetto MA, Brinkman, et al. Systematic identification of selective essential genes in Helicobacter pylori by genome prioritization and allelic replacement mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1259–1268. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1259-1268.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambaud I, Heilig R, Ferris S, Barbe V, Samson D, Galisson F, et al. The complete genome of the murine respiratory pathogen Mycoplasma pulmonis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2145–2153. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.10.2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JK, Thorp RB, Parker RF, White H, Dziedzic D, D’Arcy J, Cassell GH. Development of an aerosol model of murine respiratory mycoplasmosis in mice. Infect Immun. 1986;54:194–201. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.1.194-201.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dybvig K, Woodard A. Cloning and DNA sequence of a mycoplasmal recA gene. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:778–784. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.778-784.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dybvig K, Gasparich GE, King KW. Artificial transformation of mollicutes via polyethylene glycol- and electroporation-mediated methods. In: Razin S, Tully JG, editors. Molecular and Diagnostic Procedures in Mycoplasmology. I. Orlando: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Dybvig K, Voelker LL. Molecular biology of mycoplasmas. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:25–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dybvig K, French CT, Voelker LL. Construction and use of derivatives of transposon Tn4001 that function in Mycoplasma pulmonis and Mycoplasma arthritidis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4343–4347. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4343-4347.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dybvig K, Cao Z, French CT, Yu H. Evidence for type III restriction and modification systems in Mycoplasma pulmonis. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:2197–2202. doi: 10.1128/JB.01669-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser CF, Gocayne JD, White O, Adams MD, Clayton RA, Fleischmann RD, et al. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science. 1995;270:397–403. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher LA, Ramage E, Jacobs MA, Kaul R, Brittnacher M, Manoil C. A comprehensive transposon mutant library of Francisella novicida, a bioweapon surrogate. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1009–1014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606713104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil R, Silva FJ, Pereto J, Moya A. Determination of the core of a minimal bacterial gene set. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:518–537. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.518-537.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JI, Assas-Garcia N, Alperovich N, Yooseph S, Lewis MR, Maruf M, et al. Essential genes of a minimal bacterium. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:425–430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510013103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumulak-Smith J, Teachman A, Tu A-HT, Simecka JW, Lindsey JR, Dybvig K. Variations in the surface proteins and restriction enzyme systems of Mycoplasma pulmonis in the respiratory tract of infected rats. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:1037–1044. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson CA, III, Peterson SN, Gill SR, Cline RT, White O, Fraser, et al. Global ransposon mutagenesis and a minimal mycoplasma genome. Science. 1999;286:2165–2169. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MA, Alwood A, Thaipisuttikul I, Spencer D, Haugen E, Ernst S, et al. Comprehensive transposon mutant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14339–14344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036282100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y, Zhang B, Van Horn SF, Warren P, Woodnutt G, Burnham MKR, Rosenberg M. Identification of critical staphylococcal genes using conditional phenotypes generated by antisense RNA. Science. 2001;293:2266–2269. doi: 10.1126/science.1063566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Ehrlich SD, Albertini A, Amati G, Andersen KK, Arnaud M, et al. Essential Bacillus subtilis genes. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4678–4683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730515100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane G, Zignol M, Blades NJ, Geiman DE, Dougherty A, Grosset J, et al. A postgenomic method for predicting essential genes at subsaturation levels of mutagenesis: Application to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7213–7218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1231432100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati NT, Urbach JM, Miyata S, Lee DG, Drenkard E, Wu G, et al. An ordered, nonredundant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 transposon insertion mutants. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2833–2838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511100103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahairas GG, Lyon BR, Skurray RA, Pattee PA. Genetic analysis of Staphylococcus aureus with Tn4001. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3968–3972. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3968-3972.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniloff J. Phylogeny of mycoplasmas. In: Maniloff J, McElhaney RN, Finch LR, Baseman JB, editors. Mycoplasmas: Molecular Biology and Pathogenesis. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 549–559. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil LK, Reich C, Aziz RK, Bartels D, Cohoon M, Disz T, et al. The National Microbial Pathogen Database Resource (NMPDR): a genomics platform based on subsystem annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D347–D353. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha EPC, Blanchard A. Genomic repeats, genome plasticity and the dynamics of Mycoplasma evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:2031–2042. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Arroyo CE, Jordan J, Peacock SJ, Willby MJ, Farmer MA, Krause DC. Mycoplasma pneumoniae protein P30 is required for cytadherence and associated with proper cell development. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1079–1087. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1079-1087.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama N, Sheperd B, Falkow S. Global transposon mutagenesis and essential gene analysis of Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7926–7935. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.7926-7935.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons WL, Dybvig K. The Vsa proteins modulate susceptibility of Mycoplasma pulmonis to complement killing, hemadsorption, and adherence to polystyrene. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5733–5738. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5733-5738.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons WL, Denison AM, Dybvig K. Resistance of Mycoplasma pulmonis to complement lysis is dependent on the number of Vsa tandem repeats: shield hypothesis. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6846–6851. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.6846-6851.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons WL, Bolland JR, Daubenspeck JM, Dybvig K. A stochastic mechanism for biofilm formation by Mycoplasma pulmonis. Infect Immun. 2007;189:1905–1913. doi: 10.1128/JB.01512-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitaraman R, Denison AM, Dybvig K. A unique, bifunctional site-specific DNA recombinase from Mycoplasma pulmonis. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:1033–1040. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J-H, Ko KS, Lee J-Y, Baek JY, Oh WS, Yoon HS, et al. Identification of essential genes in Streptococcus pneumoniae by allelic replacement mutagenesis. Mol Cells. 2005;19:365–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Okai N, Nonaka H, Tsuge Y, Inui M, Yukawa H. High-throughput transposon mutagenesis of Corynebacterium glutamicum and construction of a single-gene disruptant mutant library. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:3750–3755. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3750-3755.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teachman AM, French CT, Yu H, Simmons WL, Dybvig K. Gene transfer in Mycoplasma pulmonis. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:947–951. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.4.947-951.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisburg WG, Tully JG, Rose DL, Petzel JP, Oyaizu H, Yang D, et al. A phylogenetic analysis of the mycoplasmas: basis for their classification. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6455–6467. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6455-6467.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woese CR. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:221–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, H-Y O, C-T Z. DEG: a database of essential genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D271–D272. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.