Abstract

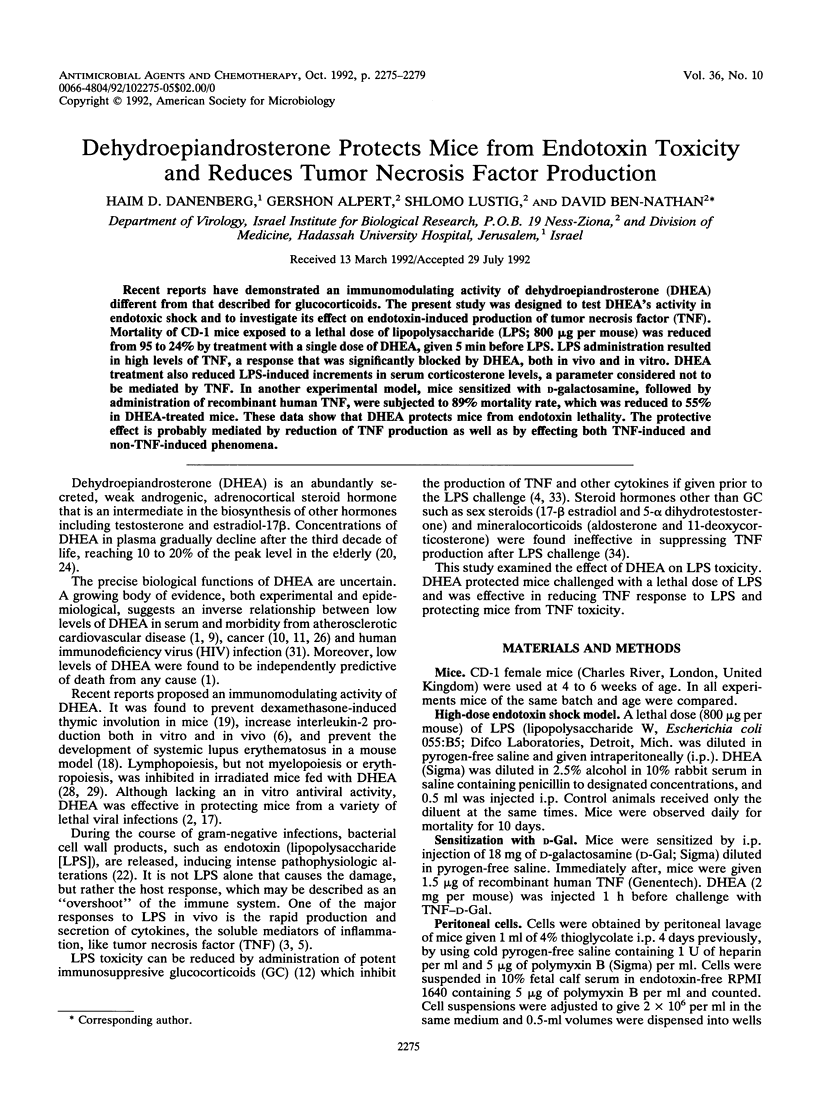

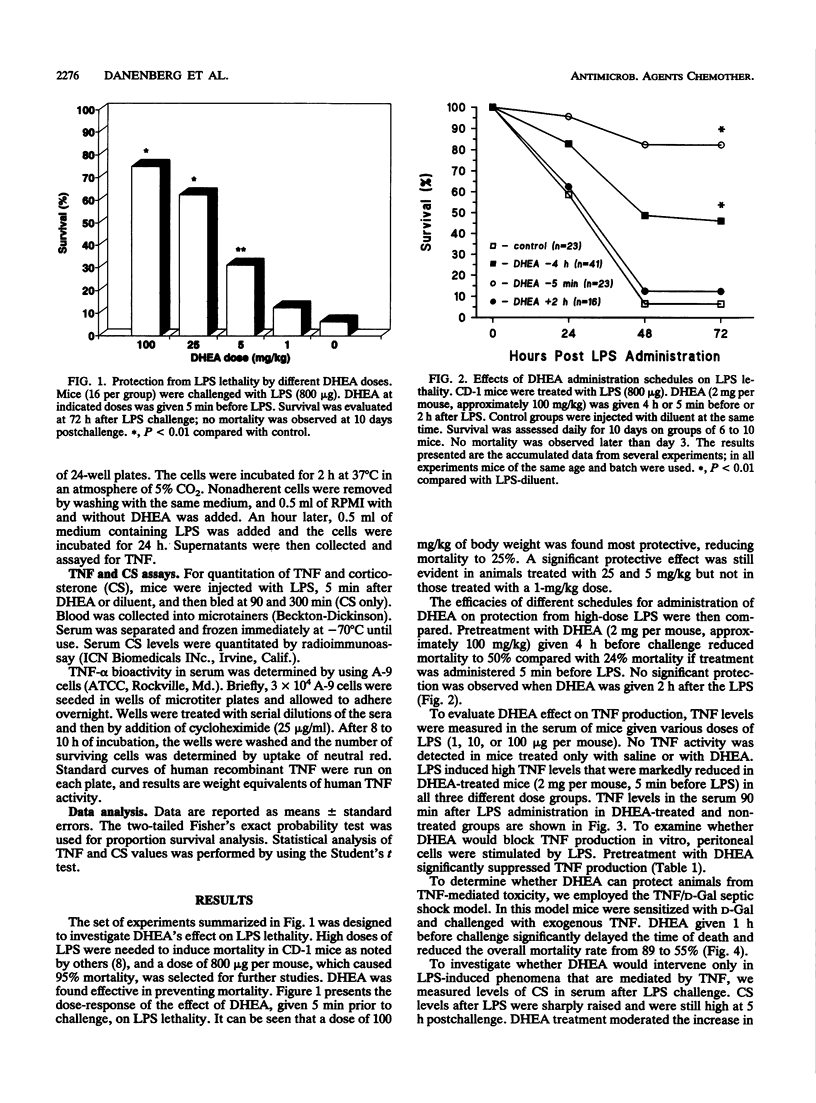

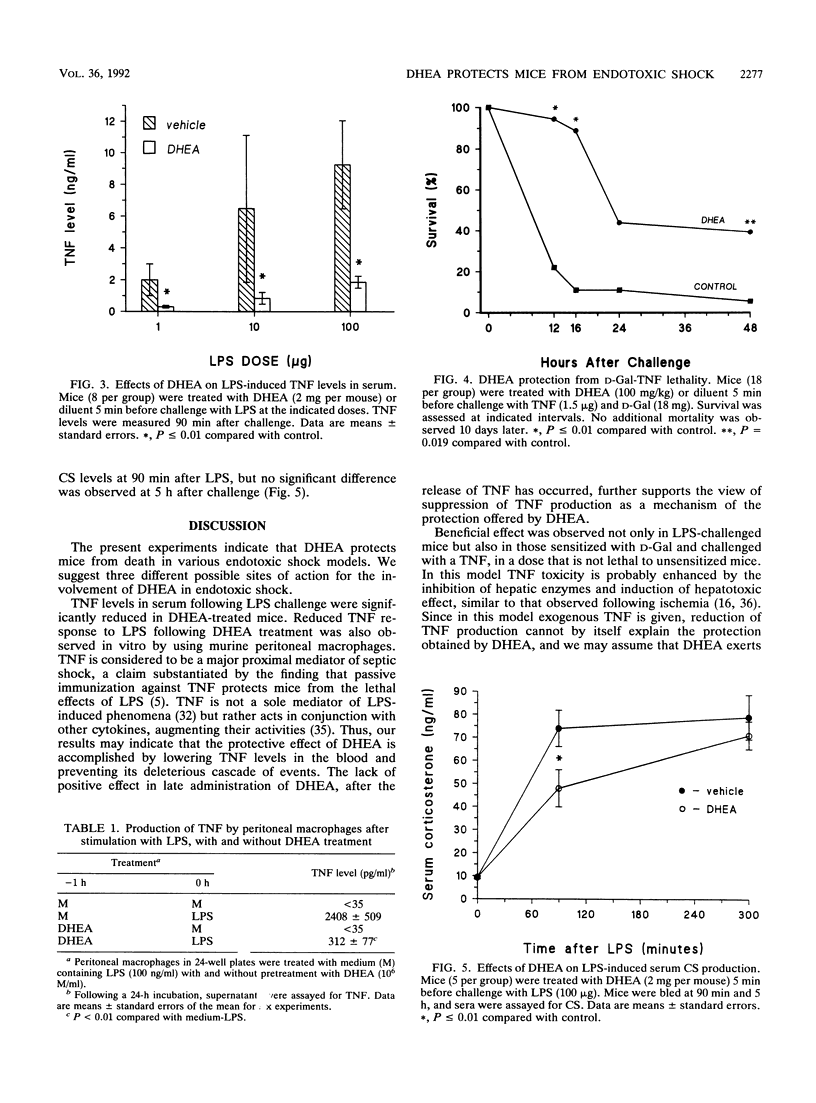

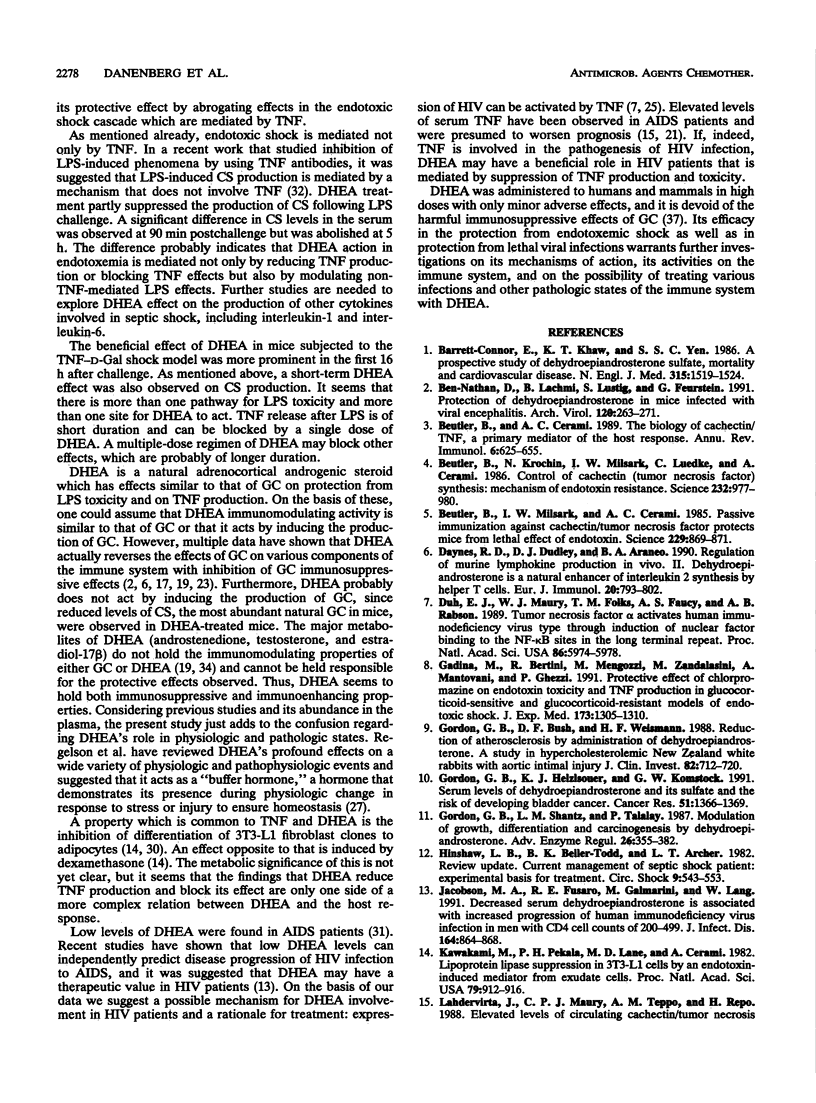

Recent reports have demonstrated an immunomodulating activity of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) different from that described for glucocorticoids. The present study was designed to test DHEA's activity in endotoxic shock and to investigate its effect on endotoxin-induced production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF). Mortality of CD-1 mice exposed to a lethal dose of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 800 micrograms per mouse) was reduced from 95 to 24% by treatment with a single dose of DHEA, given 5 min before LPS. LPS administration resulted in high levels of TNF, a response that was significantly blocked by DHEA, both in vivo and in vitro. DHEA treatment also reduced LPS-induced increments in serum corticosterone levels, a parameter considered not to be mediated by TNF. In another experimental model, mice sensitized with D-galactosamine, followed by administration of recombinant human TNF, were subjected to 89% mortality rate, which was reduced to 55% in DHEA-treated mice. These data show that DHEA protects mice from endotoxin lethality. The protective effect is probably mediated by reduction of TNF production as well as by effecting both TNF-induced and non-TNF-induced phenomena.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barrett-Connor E., Khaw K. T., Yen S. S. A prospective study of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, mortality, and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1986 Dec 11;315(24):1519–1524. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612113152405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Nathan D., Lachmi B., Lustig S., Feuerstein G. Protection by dehydroepiandrosterone in mice infected with viral encephalitis. Arch Virol. 1991;120(3-4):263–271. doi: 10.1007/BF01310481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B., Cerami A. The biology of cachectin/TNF--a primary mediator of the host response. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:625–655. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.003205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B., Krochin N., Milsark I. W., Luedke C., Cerami A. Control of cachectin (tumor necrosis factor) synthesis: mechanisms of endotoxin resistance. Science. 1986 May 23;232(4753):977–980. doi: 10.1126/science.3754653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daynes R. A., Dudley D. J., Araneo B. A. Regulation of murine lymphokine production in vivo. II. Dehydroepiandrosterone is a natural enhancer of interleukin 2 synthesis by helper T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1990 Apr;20(4):793–802. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duh E. J., Maury W. J., Folks T. M., Fauci A. S., Rabson A. B. Tumor necrosis factor alpha activates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 through induction of nuclear factor binding to the NF-kappa B sites in the long terminal repeat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Aug;86(15):5974–5978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadina M., Bertini R., Mengozzi M., Zandalasini M., Mantovani A., Ghezzi P. Protective effect of chlorpromazine on endotoxin toxicity and TNF production in glucocorticoid-sensitive and glucocorticoid-resistant models of endotoxic shock. J Exp Med. 1991 Jun 1;173(6):1305–1310. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon G. B., Bush D. E., Weisman H. F. Reduction of atherosclerosis by administration of dehydroepiandrosterone. A study in the hypercholesterolemic New Zealand white rabbit with aortic intimal injury. J Clin Invest. 1988 Aug;82(2):712–720. doi: 10.1172/JCI113652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon G. B., Helzlsouer K. J., Comstock G. W. Serum levels of dehydroepiandrosterone and its sulfate and the risk of developing bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 1991 Mar 1;51(5):1366–1369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon G. B., Shantz L. M., Talalay P. Modulation of growth, differentiation and carcinogenesis by dehydroepiandrosterone. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1987;26:355–382. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(87)90023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw L. B., Beller-Todd B. K., Archer L. T. Current management of the septic shock patient: experimental basis for treatment. Circ Shock. 1982;9(5):543–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson M. A., Fusaro R. E., Galmarini M., Lang W. Decreased serum dehydroepiandrosterone is associated with an increased progression of human immunodeficiency virus infection in men with CD4 cell counts of 200-499. J Infect Dis. 1991 Nov;164(5):864–868. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.5.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami M., Pekala P. H., Lane M. D., Cerami A. Lipoprotein lipase suppression in 3T3-L1 cells by an endotoxin-induced mediator from exudate cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Feb;79(3):912–916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.3.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann V., Freudenberg M. A., Galanos C. Lethal toxicity of lipopolysaccharide and tumor necrosis factor in normal and D-galactosamine-treated mice. J Exp Med. 1987 Mar 1;165(3):657–663. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.3.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loria R. M., Inge T. H., Cook S. S., Szakal A. K., Regelson W. Protection against acute lethal viral infections with the native steroid dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). J Med Virol. 1988 Nov;26(3):301–314. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890260310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas J. A., Ahmed S. A., Casey M. L., MacDonald P. C. Prevention of autoantibody formation and prolonged survival in New Zealand black/New Zealand white F1 mice fed dehydroisoandrosterone. J Clin Invest. 1985 Jun;75(6):2091–2093. doi: 10.1172/JCI111929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lähdevirta J., Maury C. P., Teppo A. M., Repo H. Elevated levels of circulating cachectin/tumor necrosis factor in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Med. 1988 Sep;85(3):289–291. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIGEON C. J., KELLER A. R., LAWRENCE B., SHEPARD T. H., 2nd Dehydroepiandrosterone and androsterone levels in human plasma: effect of age and sex; day-to-day and diurnal variations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1957 Sep;17(9):1051–1062. doi: 10.1210/jcem-17-9-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May M., Holmes E., Rogers W., Poth M. Protection from glucocorticoid induced thymic involution by dehydroepiandrosterone. Life Sci. 1990;46(22):1627–1631. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90394-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz M., Rapaport R., Oleske J. M., Connor E. M., Koenigsberger M. R., Denny T., Epstein L. G. Elevated serum levels of tumor necrosis factor are associated with progressive encephalopathy in children with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Dis Child. 1989 Jul;143(7):771–774. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1989.02150190021012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munck A., Guyre P. M., Holbrook N. J. Physiological functions of glucocorticoids in stress and their relation to pharmacological actions. Endocr Rev. 1984 Winter;5(1):25–44. doi: 10.1210/edrv-5-1-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orentreich N., Brind J. L., Rizer R. L., Vogelman J. H. Age changes and sex differences in serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate concentrations throughout adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984 Sep;59(3):551–555. doi: 10.1210/jcem-59-3-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn L., Kunkel S., Nabel G. J. Tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1 stimulate the human immunodeficiency virus enhancer by activation of the nuclear factor kappa B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Apr;86(7):2336–2340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratko T. A., Detrisac C. J., Mehta R. G., Kelloff G. J., Moon R. C. Inhibition of rat mammary gland chemical carcinogenesis by dietary dehydroepiandrosterone or a fluorinated analogue of dehydroepiandrosterone. Cancer Res. 1991 Jan 15;51(2):481–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regelson W., Loria R., Kalimi M. Hormonal intervention: "buffer hormones" or "state dependency". The role of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), thyroid hormone, estrogen and hypophysectomy in aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;521:260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb35284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risdon G., Cope J., Bennett M. Mechanisms of chemoprevention by dietary dehydroisoandrosterone. Inhibition of lymphopoiesis. Am J Pathol. 1990 Apr;136(4):759–769. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risdon G., Kumar V., Bennett M. Differential effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on murine lymphopoiesis and myelopoiesis. Exp Hematol. 1991 Feb;19(2):128–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin C. S., Hirsch A., Fung C., Rosen O. M. Development of hormone receptors and hormonal responsiveness in vitro. Insulin receptors and insulin sensitivity in the preadipocyte and adipocyte forms of 3T3-L1 cells. J Biol Chem. 1978 Oct 25;253(20):7570–7578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villette J. M., Bourin P., Doinel C., Mansour I., Fiet J., Boudou P., Dreux C., Roue R., Debord M., Levi F. Circadian variations in plasma levels of hypophyseal, adrenocortical and testicular hormones in men infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990 Mar;70(3):572–577. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-3-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel S. N., Havell E. A. Differential inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced phenomena by anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha antibody. Infect Immun. 1990 Jul;58(7):2397–2400. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2397-2400.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waage A., Bakke O. Glucocorticoids suppress the production of tumour necrosis factor by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocytes. Immunology. 1988 Feb;63(2):299–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waage A., Espevik T. Interleukin 1 potentiates the lethal effect of tumor necrosis factor alpha/cachectin in mice. J Exp Med. 1988 Jun 1;167(6):1987–1992. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.6.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waage A. Production and clearance of tumor necrosis factor in rats exposed to endotoxin and dexamethasone. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1987 Dec;45(3):348–355. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(87)90087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach D., Holtmann H., Engelmann H., Nophar Y. Sensitization and desensitization to lethal effects of tumor necrosis factor and IL-1. J Immunol. 1988 May 1;140(9):2994–2999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welle S., Jozefowicz R., Statt M. Failure of dehydroepiandrosterone to influence energy and protein metabolism in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990 Nov;71(5):1259–1264. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-5-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]